The function of retinoic acid (RA) during limb development is still debated, as loss and gain of function studies led to opposite conclusions. With regard to limb initiation, genetic studies demonstrated that activation of FGF10 signaling is required for the emergence of limb buds from the trunk, with Tbx5 and RA signaling acting upstream in the forelimb field, whereas Tbx4 and Pitx1 act upstream in the hindlimb field. Early studies in chick embryos suggested that RA as well as Meis1 and Meis2 (Meis1/2) are required for subsequent proximodistal patterning of both forelimbs and hindlimbs, with RA diffusing from the trunk, functioning to activate Meis1/2 specifically in the proximal limb bud mesoderm. However, genetic loss of RA signaling does not result in loss of limb Meis1/2 expression and limb patterning is normal, although Meis1/2 expression is reduced in trunk somitic mesoderm. More recent studies demonstrated that global genetic loss of Meis1/2 results in a somite defect and failure of limb bud initiation. Other new studies reported that conditional genetic loss of Meis1/2 in the limb results in proximodistal patterning defects, and distal FGF8 signaling represses Meis1/2 to constrain its expression to the proximal limb.

- Limb Development

- Meis Genes

- Retinoic Acid

- FGF8

1. Introduction

Investigation of the mechanisms underlying limb development serves as a paradigm for understanding development in general. Many signaling and transcriptional pathways converge to generate growth and patterning of the limb [1]. Early studies found that the emergence of limb buds from the trunk is dependent upon fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) signaling [2], whereas subsequent growth of the limb also requires FGF8 signaling [3][4][3,4]. During forelimb bud initiation, Tbx5 is required upstream of FGF10 [5][6][7][5,6,7] and retinoic acid (RA) is required upstream of Tbx5 [8]. During hindlimb bud initiation, Tbx4 and Pitx1 function upstream of FGF10 [9]. Subsequent proximodistal patterning of both forelimbs and hindlimbs was suggested from studies in chick embryos to require proximal-specific expression of Meis1 and Meis2 (Meis1/2) as well as RA signaling, which was proposed to activate Meis1/2 expression proximally [10][11][12][10,11,12]. However, genetic loss of RA signaling in mouse embryos using knockout mutations of RA-generating enzymes encoded by Aldh1a2 or Rdh10 resulted in no change in proximal limb Meis1/2 expression and normal limb patterning [8][13][14][8,13,14]. Here, we discuss the mechanisms of limb initiation and proximodistal patterning in the light of recent genetic studies on RA signaling and Meis1/2 function.

2. Function of RA during Forelimb Budding

The mechanism through which RA signaling regulates limb development has been controversial as chick limbs treated with RA or RAR antagonists exhibit altered proximodistal patterning [10][11][12], whereas genetic loss of

The mechanism through which RA signaling regulates limb development has been controversial as chick limbs treated with RA or RAR antagonists exhibit altered proximodistal patterning [10–12], whereas genetic loss of

Aldh1a2

or

Rdh10 in mice does not alter limb proximodistal patterning [8][13][14]. However, genetic loss of

in mice does not alter limb proximodistal patterning [8,13,14]. However, genetic loss of

Aldh1a2

or

Rdh10 does disrupt initiation of forelimb development in mice or zebrafish, although hindlimb development is not affected [8][13][15][16][17]. Mouse and zebrafish

does disrupt initiation of forelimb development in mice or zebrafish, although hindlimb development is not affected [8,13,15,21,22]. Mouse and zebrafish

Aldh1a2

mutants lack expression of

Tbx5

in trunk lateral plate mesoderm that forms the forelimb field. As

Tbx5 is essential for forelimb initiation [5][6][7] via stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [18] and activation of

is essential for forelimb initiation [5–7] via stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [23] and activation of

Fgf10 [2], RA functions upstream of these important regulators of forelimb bud initiation. Other studies that support a function for RA in forelimb bud initiation include the treatment of chick embryos with the RA synthesis inhibitor disulfiram prior to forelimb bud (wing bud) establishment that prevents forelimb bud initiation [19], plus vitamin A-deficient rat embryos that exhibit forelimb hypoplasia [20] similar to

[2], RA functions upstream of these important regulators of forelimb bud initiation. Other studies that support a function for RA in forelimb bud initiation include the treatment of chick embryos with the RA synthesis inhibitor disulfiram prior to forelimb bud (wing bud) establishment that prevents forelimb bud initiation [24], plus vitamin A-deficient rat embryos that exhibit forelimb hypoplasia [25] similar to

Rdh10

knockout mice [15]. In addition, in chicken embryos treated with beads containing an RAR antagonist, a phenotype comparable to mouse

Rdh10 mutant stunted forelimbs can be observed that leads to a shorter humerus [21].

mutant stunted forelimbs can be observed that leads to a shorter humerus [26].

Comparison of the forelimb fields of mouse

Aldh1a2

and

Rdh10

mutants revealed that RA activity, normally present throughout the trunk anteroposterior axis, is required to restrict

Fgf8

expression to an anterior trunk domain in the heart and a posterior domain (caudal epiblast or tailbud) on either side of the forelimb field.

Rdh10

mutants exhibit stunted forelimbs and lose early RA activity in the heart and forelimb domains needed to set the boundary of heart

Fgf8

expression, but RA activity still exists caudally which functions to repress caudal

Fgf8

and set its caudal expression boundary; this results in an ectopic

Fgf8

expression domain that stretches posteriorly from the heart into the forelimb field, resulting in a forelimb field

Tbx5

expression domain that is delayed and shortened along the anteroposterior axis [14].

Aldh1a2

-/- embryos lack RA activity throughout the entire trunk, resulting in ectopic

Fgf8

expression that enters the forelimb field from both the heart and the caudal regions, leading to complete loss of forelimb field

Tbx5

expression and no appearance of forelimb buds [8]. These findings, plus the observation that cultured wild-type mouse embryos treated with FGF8 fail to activate

Tbx5

in the forelimb field [14], demonstrate that the underlying cause of forelimb bud initiation defects in mutants lacking RA synthesis is excessive FGF8 activity in the trunk leading to a disruption of

Tbx5

activation in the forelimb field (Figure 1). This model, in which RA functions permissively to allow forelimb

Tbx5

activation by repressing

Fgf8

, is also supported by the observation that forelimb bud initiation can be rescued in

aldh1a2

mutant zebrafish by introducing a heat-shock-inducible dominant-negative fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor [14].

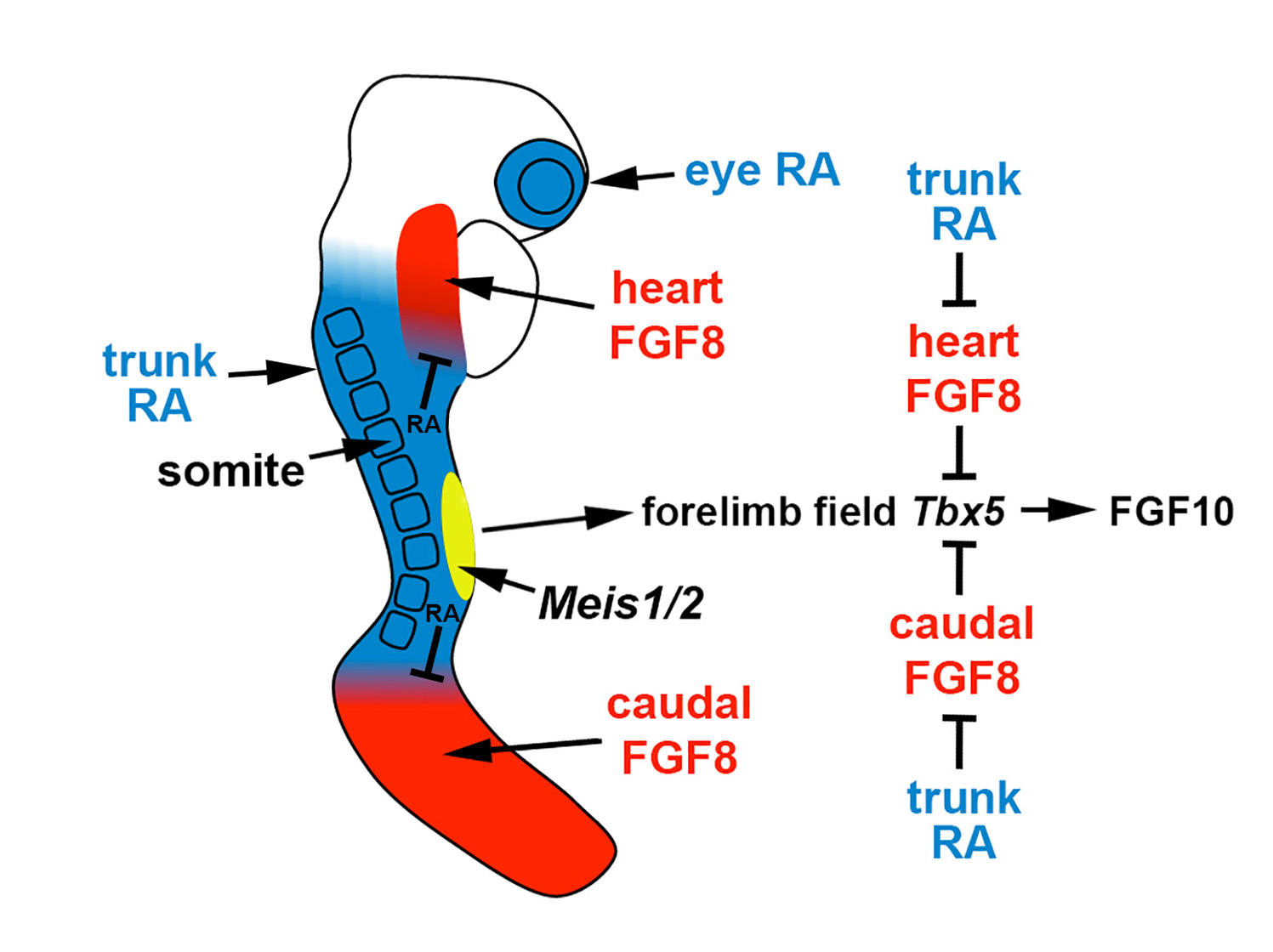

Figure 1. Role of RA signaling, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling, and Meis1/2 genes in forelimb initiation. In the E8.5 mouse embryo, the forelimb field (yellow) resides within an RA-rich trunk domain (blue) where the RA-generating enzymes encoded by Rdh10 and Aldh1a2 are expressed, thus positioned between two domains of FGF8 signaling in the heart and caudal progenitors (red). Trunk RA signaling represses Fgf8 at the borders of these two domains to permit activation of Tbx5 in the forelimb field, which then activates FGF10 signaling to stimulate limb outgrowth. Thus, RA acts permissively to activate forelimb Tbx5 expression. Genetic studies in zebrafish showing that loss of forelimb bud initiation in RA-deficient embryos can be fully rescued by reducing FGF signaling provides evidence that RA is not required to function instructively to activate forelimb Tbx5 expression. Meis1/2 genes are required for forelimb bud initiation, but it remains unclear if they activate forelimb Tbx5 or function in another manner.

3. Meis Genes and FGF Signaling Are Required for Limb Proximodistal Patterning but RA Signaling Is Dispensable

3.1. Chick Studies Support a Two-Signal Model for Limb Proximodistal Patterning

Early studies on chick limbs treated with RA suggested a role for RA in limb anteroposterior patterning [22][43]. However, subsequent studies in chicks provided evidence that RA is not required for limb anteroposterior patterning [23][24][44,45], but that sonic hedgehog (SHH) is the diffusible signaling factor required for limb anteroposterior patterning [25][46]; this requirement for SHH was confirmed in mouse knockout studies [26][47]. Other studies in chicks demonstrated that treatment of limb buds with RA, RAR antagonists, FGF8, or FGF receptor antagonists alters proximodistal patterning [10][11][12][10,11,12]. Mouse genetic loss-of-function studies verified a requirement for Fgf8 (and other Fgf genes) expressed distally in the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) to control limb proximodistal patterning, including restriction of Meis1/2 expression to the proximal limb [27][48]. However, loss of RA signaling by knockout of RA-generating enzymes encoded by Aldh1a2 or Rdh10 did not result in loss of limb proximodistal patterning or loss of proximal-specific expression of Meis1/2 [8][13][14][8,13,14].

Some researchers supporting the two-signal model raised criticisms, summarized in a review [28][49], about whether there is a total absence of RA, as measured using the RARE-lacZ RA-reporter transgene, in limb mesoderm of E9.5-E10.5 Aldh1a2 mutants (that need to be treated with a small dose of RA at E7.5 in order to survive to E10.5) or Rdh10 mutants (that survive to E10.5 without RA treatment). Aldh1a2 mutants treated with a very small dose of RA at E7.5 were shown to activate RARE-lacZ in the trunk mesoderm at E7.5-E8.5 and survive until E10.5, but at E9.5-E10.5 when limbs form, RARE-lacZ expression was not detected in the trunk lateral plate mesoderm or limb buds, indicating that the administered RA had been efficiently cleared [8]. In addition, RA titration studies on cultured Rdh10 mutants that normally have no expression of RARE-lacZ in limb or lateral plate mesoderm demonstrated that RARE-lacZ expression can be activated by as low as 0.25 nM RA, 100-fold lower than the normal level of limb RA, which is 25 nM, demonstrating that RARE-lacZ is a very sensitive RA-reporter [29]. Thus, as RA is reduced by at least 100-fold in limbs and lateral plate mesoderm of Aldh1a2 and Rdh10 mutants, it is reasonable to conclude that the concentration would be too low to provide completely normal patterning if RA is required as suggested by the two-signal model.

With regard to a potential interaction of RA and FGF8 during limb patterning, loss of limb RA in Rdh10 mutants does not alter the expression of Fgf8 in the AER [13]. This observation demonstrates that although RA does repress Fgf8 in the body axis to limit its expression to the heart and caudal regions [30][31][33,34], one should not assume that RA represses Fgf8 in other tissues.

Models based on the treatment of chick embryos with RA and RAR antagonists are weakened by the possibility of off-target effects. As RAR antagonists function as inverse-agonists that silence any gene near an RAR-bound RARE [32][50], they may dominantly repress genes that have a RARE nearby even though they normally use different regulatory elements for activation in a particular tissue. In the case of Meis1/2, the ability of RA and RAR antagonist treatments to effect expression in limb buds, even though loss of endogenous RA does not, can be rationalized by the recent discovery that these genes do require RA for full activation in trunk somites and both genes have functional RAREs [33][36]. Thus, retinoid treatment regimens may force effects on Meis1/2 expression in tissues that normally do not use RA to regulate Meis1/2.

Despite these conflicting results, a ‘two-signal model’ has been proposed in which RA generated in the trunk diffuses into the proximal region of the limb to promote proximal character by activation of Meis1/2 expression, with distal FGF8 signaling promoting distal character by repressing Meis1/2 expression [10][11][12][10,11,12]. This model is also supported by the observation that an RA-degrading enzyme encoded by Cyp26b1 is expressed in the distal limb under the control of FGF8, with CYP26B1 being required to prevent trunk RA from diffusing into the distal limb, which was reported to ectopically activate Meis1/2 expression distally [34][35][51,52]. In the Cyp26b1 knockout, Meis1/2 expression expands into the distal limb, similar to chick RA-treatment studies, but forelimb and hindlimb buds are truncated along the entire proximodistal axis, which is inconsistent with RA functioning to induce proximal identity [34][51]. In addition, in Cyp26b1 knockouts, the presence of endogenous RA in distal limbs where it should not normally exist results in a phenotype similar to exogenous RA teratogenesis with increased apoptosis and a block in chondrogenic differentiation, particularly to form the intricate skeletal structures of distal tissues such as hand/foot [36][37][53,54] or craniofacial structures [38][55]. Thus, the presence of endogenous RA in the proximal limb does not necessarily correlate with a designed function in proximodistal patterning of Meis1/2 expression, but instead may simply indicate diffusion overflow from the trunk where RA is required for body axis formation and forelimb initiation, with this RA being neither necessary nor harmful to proximal limb development. Expression of Cyp26b1 in the distal limb may not indicate a role in restricting RA signaling and sharpening an RA gradient to set the boundary of Meis1/2 expression, but may simply function to eliminate RA signaling distally where it is harmful to distal limb development. This would be similar to the function of the related RA-degrading enzyme CYP26A1 in the caudal body axis which functions to remove RA that interferes with body axis extension [39][40][56,57], thus restricting RA to the trunk/caudal border where RA is required for spinal cord development (mouse and zebrafish) and somitogenesis (mouse but not zebrafish) [41][16].

3.2. Mouse Genetic Studies Support a One-Signal Model for Limb Proximodistal Patterning

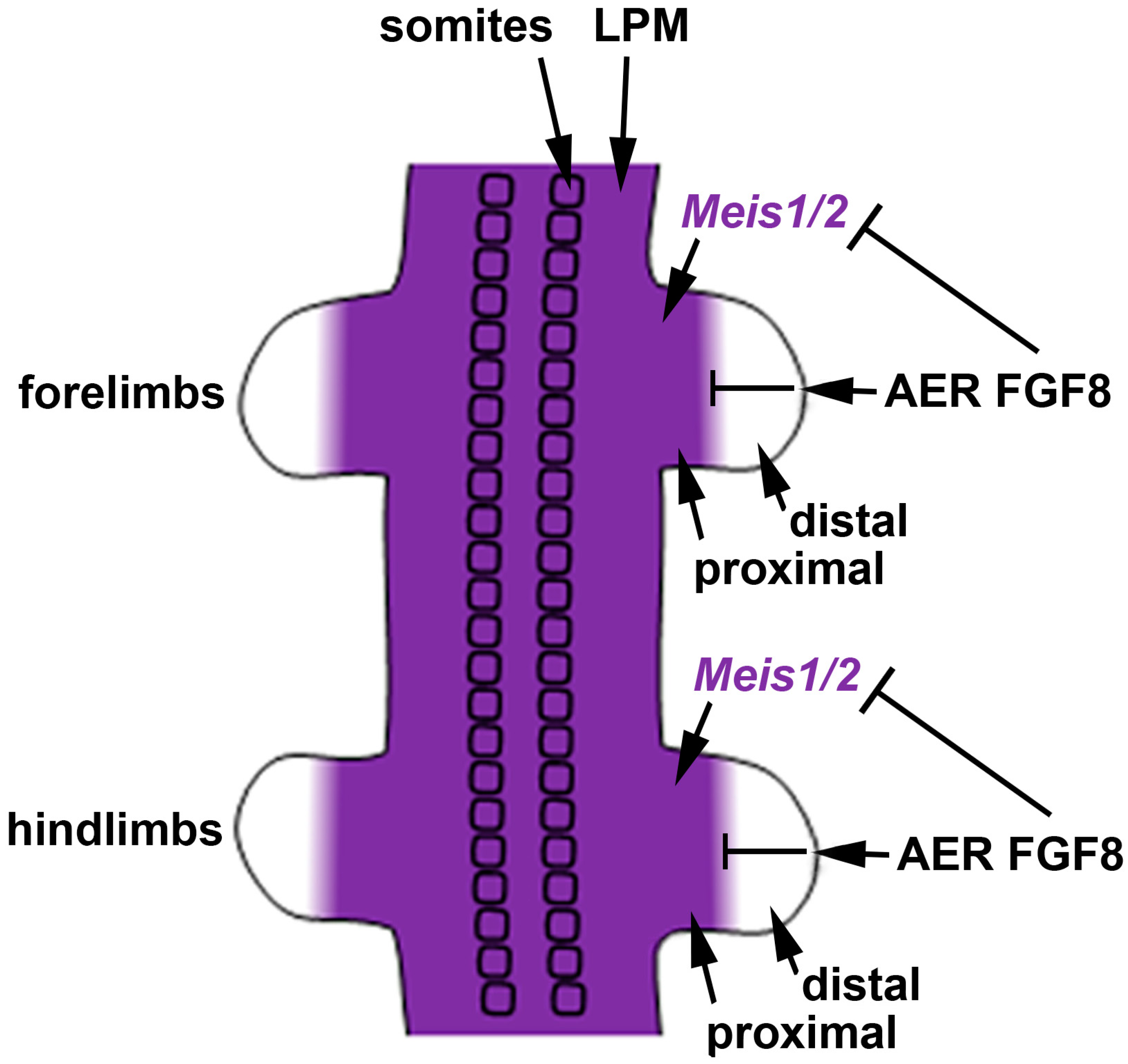

We previously suggested that the most parsimonious model for limb proximodistal patterning is a "one-signal model" that is driven by distal FGFs (including FGF8) that stimulate outgrowth, repress Meis1/2 to generate proximodistal patterning, and activate Cyp26b1 to remove distal RA from diffusing in from the trunk that would result in limb teratogenesis [42][18]. Recent studies reported that conditional genetic loss of Meis1/2 in the mouse limb results in proximodistal patterning defects [43][58]. Additionally, it was reported that restriction of Meis1/2 expression to the proximal limb is controlled by the repressive action of distal FGFs (including FGF8) expressed in the AER [43][58]. As the AER does not form until after the proximal limb is formed, thus delaying production of distal FGFs until after limb bud initiation [32], this results in early Meis1/2 expression throughout the limb. After the AER is established, Meis1/2 expression is repressed by distal FGFs, thus creating a boundary of Meis1/2 expression that leaves it in a proximal position as the distal limb continues to grow free of Meis1/2 expression (Figure 2).