Musculoskeletal disorders and the following pain were common in most people’s daily life, and the musculoskeletal pain caused by musculoskeletal disorders was the second most common cause of disability. Many established factors, such as physical, biological, cognitive, behavioral, social, and occupation, were correlated with the pain following musculoskeletal disorders

- Multi-Modal Therapies for Kinesiophobia

1. Introduction

Fear was considered to be an explanation of why pain and associated outcomes such as disability persist once the body injury had healed[1][2] [5,6], and the fear-avoidance model of pain was one of the frameworks which could explain the development and persistence of the pain and disability following a musculoskeletal injury[3][4] [7,8]. According to this model, people with a trait tend to have fear and catastrophic thoughts in response to pain were more at risk of developing chronic musculoskeletal pain after an injury than people who did not have this tendency[2][4] [6,8]. These people over-reacted in response to actual or potential threats, developing avoidance behaviors to prevent a new injury/re-injury[2] [6]. Fear in relation to pain had been described with various conceptual definitions, among which pain-related fear, fear-avoidance beliefs, fear of movement, and kinesiophobia were the most commonly used[5] [9].

Kinesiophobia was one of the most commonly used conceptual definitions which could describe fear in relation to pain[6] [10]. Kinesiophobia (also known as the fear of movement) was defined as an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear to carry out a physical movement due to a feeling of vulnerability to a painful injury or re-injury[6] [10]. It could be acquired through a direct aversive experience such as pain and trauma or through social learning such as observation and instruction [7][11]. Kinesiophobia had been associated with pain, disability, and quality of daily life to some extent[8] [12]. The prevalence of kinesiophobia in chronic pain was from 50% to 70%[9][10].

The objective of rehabilitation is to recover physical exercises’ performance, regain the capacity of daily activities, and restore social functions. In recent years, studies on the rehabilitation of musculoskeletal disorders had begun to focus on the fear in relation to pain[11][12][15,16]. The fear in relation to pain would cause people to produce fear-avoidance and had a negative effect on their quality of life. Therefore, not only the rehabilitation at the physical level but also the rehabilitation at the psychological level should be paid attention to[13][14][15][16]. At the same time, as mentioned above, kinesiophobia could be acquired through many different ways (e.g., personal experience, social learning)[7], therapies combined multi-modal from both psychological and physical perspectives had become increasingly popular[11][17][18]. However, at present, only a few studies focus on the advantage of multi-modal therapies over uni-modal therapies, and most of the studies on the rehabilitation of musculoskeletal disorders were limited to specific musculoskeletal disorders. There was a lack of high-quality evidence from the macro-perspective. To answer this question, the terms “physical therapy” and “psychological therapy” should be defined in this review at first. [19][20][21][22]

In this review, the terms “physical therapy” and “psychological therapy” were defined as follows. “Physical therapy” was the therapy included: (1) exercise/training session or advice with a private plan; (2) passive physical therapies such as usual care; (3) treatments provided by professional therapists or medical staff without any psychological education. It should be emphasized that exercise/training advice without a private plan, waiting lists and interventions without any control, such as keeping normal daily life, would be excluded.

“Psychological therapy” was the therapy include (1) psychological education; (2) cognition-behavior therapy; (3) perceptive stimulation in non-injured body areas such as virtual reality equipment, laser, and relaxation; (4) therapeutic milieu involves interpersonal communication such as group session and feedback session. It should be emphasized that if the doctor-patient communication in the intervention involved only an explanation of the treatment or only guidance of exercise or only supervision in training, the intervention wouldn’t be regarded as psychological therapy.

Moreover, a quantitative indicator was required to assess the fear of movement, and there was not a specific tool to assess fear of movement directly[5] [9]. The term “kinesiophobia” would be used. People with kinesiophobia would change their movements to avoid pain and adjust their motor behaviors[8] [12]. The processing of pain and pain-related information in people with musculoskeletal disorders could be related to how kinesiophobia was perceived[2319] [23]. Therefore, a greater degree of kinesiophobia predicted greater levels of fear of pain and a great inclination to avoid physical movements[2420] [24].

Kinesiophobia could be measured by the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) [2521][25]. Since the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia had good validity in the quantization of kinesiophobia, the change of TSK scores would reflect the effect of therapy and be taken as a comparative indicator of therapy effect to some extent[2622][2723] [26,27]. In the original version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, participants would be asked to respond to how much they agreed with each of the 17 items, and the ratings available were: (1) disagree; (2) partially disagree; (3) partially agree; (4) strongly agree. The score of each item varies from 1–4 or 0–3. The responses were summed, and the generated score, which ranges from 17 to 68 or from 0 to 51[9][2521] [13,25]. However, the TSK scores were usually reported as a secondary outcome, and that there was a limited number of studies that focus on the treatments for kinesiophobia. It made that a special study search strategy, information extraction, and data processing methods need to be applied.

2. Systematic Review of Related Studies

2.1. Study Selection, Information, and Original Data

In the database PubMed, by the search term “(kinesiophobia[Title/Abstract]) AND ((randomized) or (randomised)[Title/Abstract]) NOT ((design) or (protocol)[Title])”, and the limitation of “randomized controlled trials”, 55 studies had been screened out. In the database Medline (EBSCO), by the search term “AB kinesiophobia and AB (randomized or randomised) NOT TI (design or protocol)”, and the range of “Cochrane Central Register of Trials, Medline with Full Text, and CINAHL”, 507 studies had been screened out. In the database Ovid, by the search term “(kinesiophobia and (randomized or randomised) .ab not (design or protocol) .at” typed in the tool “Multi-Field Search”, and the limitation of English, 480 studies had been screened out. All the results would be downloaded and imported into EndNote X9 for further screening.

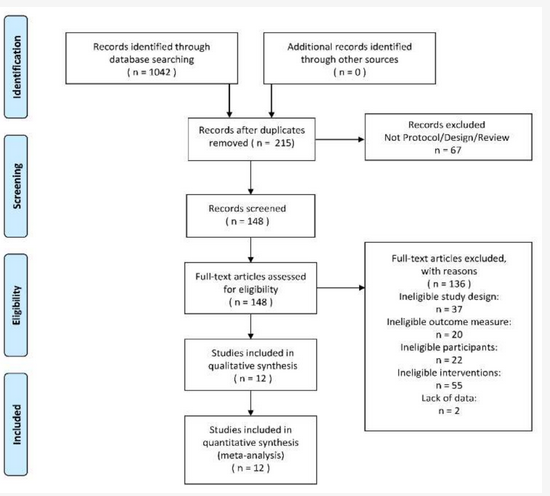

After deduplication and applying the exclusion criteria, 12 studies[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39] [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] of the total 1042 studies were included for analysis. The flow diagram could be seen in Figure 1. Based on the information of all the full texts included, the result of data collection and a summary measure of each included study could be seen in Table 1 and Table 2.

Figure 1. The PRISMA 2009 flow diagram of search and study selection.

Table 1. The result of data collection.

| Study Design | Characteristics of Participants | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Baseline (T0) | Follow-Up Times (T1) | Follow-Up Times (T2) | Follow-Up Times (T3) | |||||||

| Statistics of Heterogeneity Test | 95% CI of T2 | ||||||||||

| Version of TSK | Multi-Modal Therapy Group | Uni-Modal Therapy Group | Mean Age | ||||||||

| TSK + | N0 | TSK | Type of Pain | ||||||||

| + | Duration | N | 1 | TSK | + | Duration | N2 | TSK + | |||

| Language | R | Intervention | Duration of Intervention (Weeks) | N | Intervention | ||||||

.

The forest plot of the subgroup analysis: (

) The subdivisions of different types of pain; (

) The subdivisions of different ranges of participants’ mean age; (

) The subdivisions of different durations of treatments; (

) The subdivisions of different follow-up times; (

) The subdivisions of different types of physical therapy in control groups.

The result of heterogeneity test of subgroup analysis.

| Outcome Subdivision | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI of I | 2 | ||

| Subgroups | |||

| Prediction Intervals | |||

| Statistics of Heterogeneity Test | 95% CI of T2 | 95% CI of I2 | Prediction Intervals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | Q | I2 | Tau | ||||||

| Duration of Intervention (Weeks) | N | ||||||||

| Duration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 3 | |||||

| 2 | LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL |

Meta-regression result: The follow-up times and the SMD of effect.

| Meta-Regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | Covariate | |||

| Item | Index | Duration of Treatments | Mean Age of Participants | Follow-Up Times (Week) |

| Gardner 2019 [3026] | English | 0.820 | ||||||||

| df | Q | I | ||||||||

| Education + Patient-led goal setting intervention | ||||||||||

| 2 | Tau | |||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||||

| 2 | LL | |||||||||

| 37 | Standardised advice to exercise with a plan | 8 | ||||||||

| UL | LL | |||||||||

| 38 | ||||||||||

| 323.8 | ||||||||||

| 44.51 | Chronic Low-back Pian | |||||||||

| UL | LL | UL | ||||||||

| 97% | 29.62 | 3.63 | 5.37 | 79% | 85% | 0.00 * | ||||

| Nambi 2020-Arm1[3935] | English | 0.820 | Virtual reality training | 4 | 20 | Isokinetic training with a plan | 4 | 20 | 23.00 | Chronic Low-back Pian |

| Nambi 2020-Arm2 | English | 0.820 | Virtual reality training | 4 | 20 | Conventional training with a plan | 4 |

| Gardner 2019 [34] | Gardner 2019[26] | OG | 36.60 (7.50) | 37 | 29.30 (6.90) | 8 | 37 | 30.00 (5.30) | 16 | 37 | 31.20 (7.90) | 48 | 37 |

| 20 | |||||||||||||

| 26.43 (3.50) | |||||||||||||

| 24 | |||||||||||||

| 21.29 |

| Number of obs | N | 24 | 24 | 24 | |||||||||||||||||

| CG | 39.90 (9.30) | 38 | 39.40 (8.30) | 8 | 38 | 39.30 (8.10) | 16 | 38 | 37.30 (8.00) | 48 | 38 | ||||||||||

| 23 | 1549.94 | 99% | 34.21 | 3.37 | 4.09 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.00 * | 19.33 | ||||||||||||

| CNP | 6 | 181.84 | 97% | 28.79 | 3.39 | 5.70 | 78% | 85% | 0.00 * | 16.59 | |||||||||||

| REML estimate of between-study variance | Tau2 | 24.39 | 19.08 | 29.86 | |||||||||||||||||

| Nambi 2020-Arm1 [43][35] | UEMD | OG | 57.52 (4.80) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 23.25 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronic Low-back Pian | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 20 | 20.12 (2.50) | 24 | 19 | 4.02 | ||||||||||||||||

| % residual variation due to heterogeneity | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 50% | 0.73 | 0 * | 1.18 | ||||||||||||||||||

| I-squared_res | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 0% * | 62% | 0.00 * | 26.55 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 98.38% | 96.11% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm1 [3632][40] | Turkish | 0.806 | Manual therapy + Supervised home exercise + Pain neuroscience education | 4 | 20 | Manual therapy + Supervised home exercise | |||||||||||||||

| CG | 58.11 (4.50) | 20 | 27.54 (3.80) | 4 | 20 | 21.21 (2.40) | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | 19 | 40.50 | Chronic Low-back Pian | ||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | Mean Age of Participants | 20–30 | 5 | 20 | 49.24 | 90% | 2.71 | 0.39 | 1.02 | 56% | 77% | 6.14 | 18.38 | ||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm2 | Turkish | 0.806 | Manual therapy + Supervised home exercise + Pain neuroscience education | 4 | 20 | Supervised home exercise | 4 | 18 | 39.94 | Chronic Low-back Pian | |||||||||||

| Nambi 2020-Arm2 | OG | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 99.58% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 57.52 (4.80) | 20 | 30–40 | 26.43 (3.50) | 6 | 4 | 20 | 20.12 (2.50) | 24 | 127.78 | 95% | 5.34 | 19 | 0.70 | 1.28 | 73% | 83% | 0.14 | 14.10 | |||

| Gustavsson 2006 [2824][32] | Swedish | 0.910 | Relaxation treatment | 7 | 13 | Treatment as usual | 20 | 16 | 37.48 | Chronic Neck Pain | |||||||||||

| CG | 57.93 (4.30) | 20 | 46.21 (4.10) | 4 | 20 | 38.64 (3.90) | 24 | 19 | |||||||||||||

| 40+ | 8 | 63.73 | 87% | 0.61 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 53% | 73% | 1.01 | 7.05 | |||||||||||

| Javdaneh 2020[3834] [42] | Persian | 0.920 | Cognitive functional therapy + Scapular exercise | 6 | 24 | Scapular exercise with a plan | 6 | 24 | 29.50 | Chronic Neck Pain | |||||||||||

| Duration of Treatments | 0–3 weeks | 3 | 5.31 | 44% | 0.58 | 0 * | 0.98 | 0% * | 57% | 7.03 | 16.29 | ||||||||||

| Ris 2016 [3228][36] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4–6 weeks | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Proportion of between-study variance explained | Adj R-squared | 14.46% | 33.10% | −4.74% | |||||||||||||||||

| English | 0.820 | Physical training + Specific exercises + Pain education | 16 | 101 | |||||||||||||||||

| 28 | 47.53 | Chronic Neck Pain | |||||||||||||||||||

| Yilmza 2017 [3733][41] | Turkish | 0.806 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm1 [40][32] | OG | 44.35 (4.30) | 20 | 35.55 (5.75) | 4 | 20 | 35.19 (3.99) | 6 | |||||||||||||

| Pain education | 16 | 99 | 45.15 | Chronic Neck Pain | |||||||||||||||||

| 1065.22 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bahat 2015 [33] | Dutch | 0.780 | Cervical kinematic training + Interactive Virtual Reality training | 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Virtual walking therapy | 2 | 22 | |||||||||||||||||||

| CG | 45.10 (4.45) | 19 | 41.63 (5.23) | 4 | 19 | 42.21 (5.04) | 6 | 99% | 45.64 | 3.73 | 4.74 | 89% | 91% | 0.00 * | 23.12 | ||||||

| 16 | Cervical kinematic training with a plan | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7–9 weeks | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 40.88 | Chronic Neck Pain | |||||||||||||||||||

| 54.64 | 91% | 13.68 | 1.95 | 4.86 | 59% | 78% | 0.00 * | 14.31 | |||||||||||||

| 9+ weeks | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Physiotherapy | 2 | 22 | 25.14 | Non-special Low-back Pain | |||||||||||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm2 | OG | 44.35 (4.30) | 20 | 35.55 (5.75) | 4 | 20 | 35.19 (3.99) | 6 | |||||||||||||

| Tompson 2016 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2.39 | 58% | 4.38 | 0 * | 6.85 | 0% | 69% | N/N | N/N | ||||||||||||

| Follow-up Times | 0–12 weeks | 14 | 965.81 | 99% | 35.78 | 3.40 | 4.34 | 87% | 89% | 0.00* | 20.28 | ||||||||||

| 13–24 weeks | 6 | 380.24 | 98% | 53.32 | 4.90 | 7.19 | 85% | 89% | 0.00 * | 25.90 | |||||||||||

| 24+ weeks | 327.26 | 96% | 27.47 | 3.63 | 5.34 | 78% | 84% | 0.00 * | 19.82 | ||||||||||||

| Passive Therapy | 6 | 546.14 | 99% | 39.00 | 3.13 | 4.36 | 88% | 91% | 0.00 * | 23.27 |

df: Degree of freedom; LL: Lower limit; UL: Upper limit; *: the true value is less than 0; CNP: Chronic neck pain; CLBP: Chronic low-back pain; UEMD: Upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders; N/N: when df = 1, the t-value could not be calculated so that the prediction intervals could not be estimated as well.

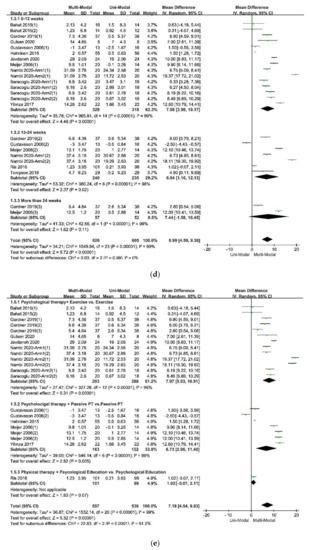

2.4.2. Meta-Regression

The large heterogeneity within the included studies made it necessary to do a meta-regression. The meta-regression made using STATA

12 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA), and the results can be seen in

and

.

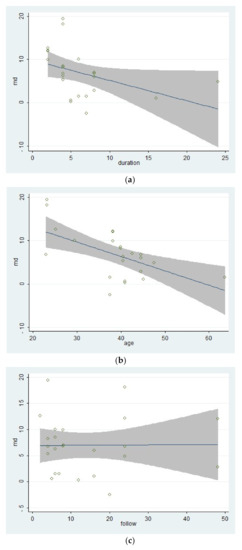

The bubble chats of the results of the three covariates in the meta-regression: (

) The duration of treatments; (

) Mean age of participants; (

) Follow-up times.

| Statistical Significance | ||||

| P | ||||

| -value | 0.052 | 0.002 | 0.963 | |

| Monte Carlo Permutation Test | Adjusted P-value | 0.139 | 0.008 | 1.000 |

The result of the meta-regression calculation for the covariate “follow-up times” showed that the proportion of the residual variation due to heterogeneity, which could be represented by the statistic “I-squared_res”, was 99.58%. It meant that only 0.42% of the residual variation could be explained by between-study variance. And the result of the meta-regression calculation of the covariate “mean age of participants” showed that the proportion of the residual variation due to heterogeneity, which could be represented by the statistic “I

” (I-squared_res), was 96.11%. It meant that only 3.89% of the residual variation could be explained by between-study variance. The proportion of the heterogeneity could be explained by between-study variance, which could be represented by the statistic “adjusted R

” (Adj R-squared), which was 33.10%. The result of the meta-regression calculation of the covariate “duration of treatments” showed that the proportion of the residual variation due to heterogeneity, which could be represented by the statistic “I

” (I-squared_res), was 98.38%. It meant that only 1.62% of the residual variation could be explained by between-study variance. The proportion of the heterogeneity could be explained by between-study variance, which could be represented by the statistic “adjusted R

” (Adj R-squared), which was 14.46%. Lastly, the result of the Monte Carlo Permutation Test for Single Covariate of Meta-regression, the adjusted p-value changed from 0.139 to 0.008 to 1000 within the covariate “duration of treatments”, “mean age of participants”, and “follow-up times”, indicating that there might not be the type I error existing within the included studies. The bubble chats of the results of the three covariates in the meta-regression.

2.4.3. Statistical Power

According to the result shown in

, the meta-analysis’s statistical power was higher than any included study. Moreover, the statistical power of the heterogeneity analysis was less than that of the pooled effect because of the interactions between the covariables. The result was consistent with the previous hypothesis.

The result of statistical power test of all included studies and meta-analysis.

e

e

| Study | Statistical Power of Study | Subdivisions | Subgroups | Statistical Power of Effect Combination | Statistical Power of Heterogeneity Test | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gardner 2019 (1) [26] | 13.45% | Types of Pain | CLBP | 100.00% | 51.76% | ||||||||||||||||

| Gardner 2019 (2) | 18.34% | CNP | 48.92% | 39.09% | |||||||||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gardner 2019 (3) | 8.15% | UEMD | 100.00% | 22.36% | |||||||||||||||||

| Nambi 2020-Arm1 (1)[35] | 5.62% | Follow-up times | 0–12 weeks | 100.00% | 61.90% | ||||||||||||||||

| Nambi 2020-Arm1 (2) | 11.75% | 13–24 weeks | 99.66% | 39.09% | |||||||||||||||||

| 29] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nambi 2020-Arm2 (1) | 17.54% | 24+ weeks | 48.16% | 16.58% | |||||||||||||||||

| [37 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nambi 2020-Arm2 (2) | 5.82% | Mean Age of Participants | 20–30 | 100.00% | 35.41% | ||||||||||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm1 (1)[32] | 14.54% | 30–40 | |||||||||||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 99.99% | 39.09% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm1 (2) | 6.13% | 40+ | 99.42% | 45.79% | |||||||||||||||||

| CG | |||||||||||||||||||||

| English | 0.820 | Cognitive-behavioural physiotherapy + Progressive neck exercise | 24 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 45.55 (4.10) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 44.94 (4.70) | 4 | 18 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Progressive neck exercise | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 44.88 (5.10) | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gustavsson 2006 [32 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm2 (1) | 5.61% | Physical Therapy in Control Groups | Active Exercise | 100.00% | 57.10% | ||||||||||||||||

| ][24] | OG | 26.00 (7.46) | 13 | 27.00 (5.22) | 7 | 13 | 29.00 (5.22) | 20 | 13 | ||||||||||||

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm2 (2) | 21.80% | Passive Therapy | 100.00% | 39.09% | |||||||||||||||||

| Helminen 2015[3531] [39] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| CG | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Finnish | 0.890 | Cognitive-behavioral group intervention contains skill training plan | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 29.50 (1.67) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 55 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 32.00 (0.00) | 7 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ordinary general practitioner care | 6 | 56 | 63.64 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 30.00 (2.00) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Knee Osteoarthritis Pain | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gustavsson 2006 (1)[24] | 19.81% | Duration of Treatments | 0–3 weeks | 100.00% | 27.16% | ||||||||||||||||

| Meijer 2006 [3127][35] | Dutch | 0.780 | Treatment combined physical and psychological sessions | 2 | 20 | Usual care by occupational health services | 2 | 14 | 38.14 | ||||||||||||

| Javdaneh 2020 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||

| [42][34] | OG | 50.00 (5.23) | 24 | 37.07 | 21.00 (5.22) | 97% | 6 | 24 | 13.05 | 1.02 | 3.15 | 74% | 90% | N/N | N/N | ||||||

| Gustavsson 2006 (2) | 11.61% | 4–6 weeks | 100.00% | 54.51% | |||||||||||||||||

| Gulsen 2020 [3430][38] | Turkish | 0.806 | Immersive Virtual Reality + Exercise | 8 | 8 | Exercise with a plan | 8 | 8 | 42.50 | Fibromyalgia | |||||||||||

| CG | 49.00 (4.78) | 24 | Physical Therapy in Control Groups | ||||||||||||||||||

| Javdaneh 2020[ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Active Exercise | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 34] | 56.06% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7–9 weeks | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 30.00 (3.55) | 6 | 24 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 55.56% | 35.41% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 405 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ris 2016 | [36] | 398 | [ | ||||||||||||||||||

| 28] | OG | 37.80 (0.69) | 101 | 36.57 (4.50) | Average | 0.829 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 38.7 |

| Study | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | ||||||||||||

| 101 | ||||||||||||

| Ris 2016[28] | 64.57% | |||||||||||

| 9+ weeks | 14.78% | 16.58% | ||||||||||

| CG | 37.70 (0.71) | 99 | 37.49 (4.50) | 16 | 99 | |||||||

| Bahat 2015 (1) | ||||||||||||

| [ | ||||||||||||

| 24] | 67.83% | Total | 100.00% | 77.95% | ||||||||

| Bahat 2015 [33][25] | OG | 32.75 (6.80) | 16 | 30.13 (5.70) | 5 | 16 | 31.23 (6.50) | 12 | 14 | |||

| Bahat 2015 (2) | 9.84% | |||||||||||

| CG | 30.38 (5.80) | 16 | 28.64 (9.90) | 5 | 14 | 30.00 (5.90) | 12 | 12 | ||||

| Tompson 2016[29] | ||||||||||||

| Tompson 2016 [37][29] | OG | 36.70 (7.10) | 29 | 32.00 (14.11) | 24 | 29 | ||||||

| CG | 33.60 (9.00) | 28 | 33.80 (15.04) | 24 | 28 | |||||||

| Yilmza 2017 [41][33] | OG | 43.72 (4.32) | 22 | 29.56 (4.04) | 2 | 22 | ||||||

| CG | 40.36 (5.61) | 22 | 38.70 (5.44) | 2 | 22 | |||||||

| Helminen 2015 [39][31] | OG | 35.00 (1.25) | 55 | 33.00 (1.05) | 6 | 55 | ||||||

| CG | 33.30 (1.35) | 56 | 32.50 (1.33) | 6 | 56 | |||||||

| Meijer 2006 [35][27] | OG | 38.90 (1.51) | 20 | 29.10 (1.54) | 8 | 20 | 25.80 (2.65) | 24 | 20 | 26.40 (1.90) | 48 | 20 |

| CG | 40.91 (1.81) | 14 | 41.00 (1.68) | 8 | 14 | 39.90 (3.16) | 24 | 14 | 40.40 (2.65) | 48 | 14 | |

| Gulsen 2020 [38][30] | OG | 49.00 (4.44) | 8 | 35.00 (7.41) | 8 | 8 | ||||||

| CG | 47.00 (7.22) | 8 | 40.00 (5.37) | 8 | 8 | |||||||

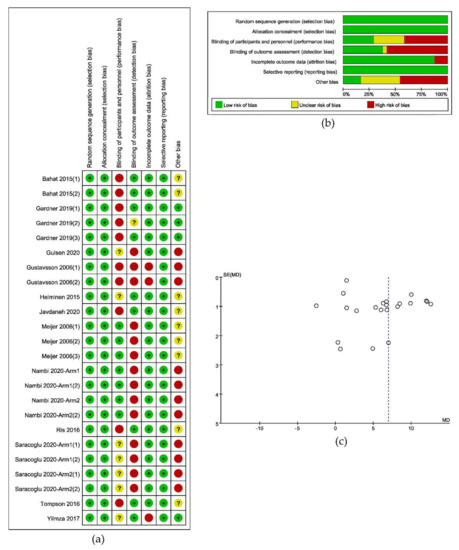

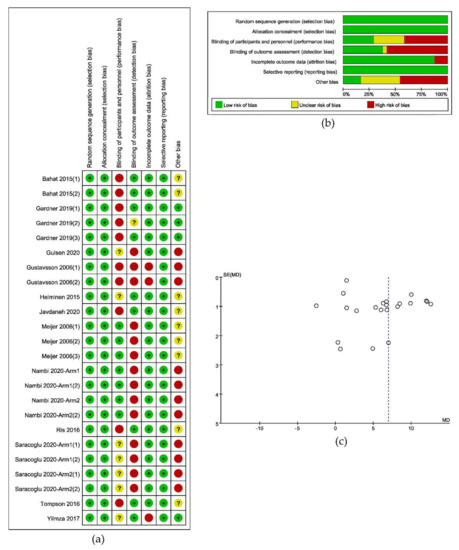

2.2. Risk of Bias

The result of the criteria for judging the risk of bias in the “Risk of bias assessment tool” would be shown in

a,b. A funnel plot of the included studies, as in

c, illustrated the risk of bias across studies and showed the relationship between the sample size and the effect. And the result of the assessment of evidence quality, which was made by following the GRADE, would be put into the

.

Results of risk of bias analysis: (

) Risk of bias summary; (

) Graph of risk of bias; (

) Funnel plot of included studies.

2.3. Data Extraction and Management

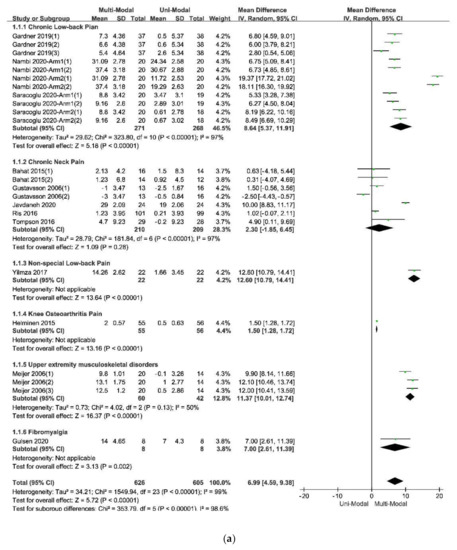

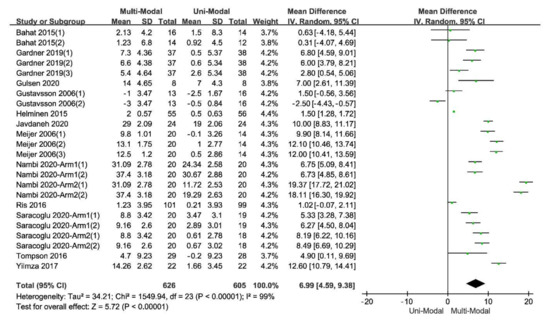

In the comparison of multi-modal interventions and uni-modal interventions with the scores of TSK as the outcome, all the 12 included studies were divided into 24 independent trials. The result of original data processing was shown in

, and the forest plots of the pooled effect, which were calculated by RevMan5.3, were shown in

.

The forest plot of the comparison between the multi-modal therapies and uni-modal therapies.

The result of original data processing.

| Study | Duration of Intervention (Weeks) | Follow-Up Times (Weeks) | Mean Age | Experiment | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | SD | N | MD | SD | N | ||||

| Gardner 2019 (1) [26] | 8 | 8 | 44.51 | 7.30 | 4.36 | 37 | 0.50 | 5.37 | 38 |

| Gardner 2019 (2) | 8 | 16 | 44.51 | 6.60 | 4.38 | 37 | 0.60 | 5.34 | 38 |

| Gardner 2019 (3) | 8 | 48 | 44.51 | 5.40 | 4.64 | 37 | 2.60 | 5.34 | 38 |

| Nambi 2020-Arm1 (1) [35] | 4 | 4 | 23.00 | 31.09 | 2.78 | 20 | 24.34 | 2.58 | 20 |

| Nambi 2020-Arm1 (2) | 4 | 24 | 23.00 | 37.40 | 3.18 | 20 | 30.67 | 2.88 | 20 |

| Nambi 2020-Arm2 (1) | 4 | 4 | 23.25 | 31.09 | 2.78 | 20 | 11.72 | 2.53 | 20 |

| Nambi 2020-Arm2 (2) | 4 | 24 | 23.25 | 37.40 | 3.18 | 20 | 19.29 | 2.63 | 20 |

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm1 (1)[32] | 4 | 4 | 40.50 | 8.80 | 3.42 | 20 | 3.47 | 3.10 | 19 |

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm1 (2) | 4 | 6 | 40.50 | 9.16 | 2.60 | 20 | 2.89 | 3.01 | 19 |

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm2 (1) | 4 | 4 | 39.94 | 8.80 | 3.42 | 20 | 0.61 | 2.78 | 18 |

| Saracoglu 2020-Arm2 (2) | 4 | 6 | 39.94 | 9.16 | 2.60 | 20 | 0.67 | 3.02 | 18 |

| Gustavsson 2006 (1)[28] | 7 | 7 | 37.48 | -1.00 | 3.47 | 13 | -2.50 | 1.67 | 16 |

| Gustavsson 2006 (2) | 7 | 20 | 37.48 | -3.00 | 3.47 | 13 | -0.50 | 0.84 | 16 |

| Javdaneh 2020[34] | 6 | 6 | 29.50 | 29.00 | 2.09 | 24 | 19.00 | 2.06 | 24 |

| Ris 2016 [28] | 16 | 16 | 45.15 | 1.23 | 3.95 | 101 | 0.21 | 3.93 | 99 |

| Bahat 2015 (1)[24] | 5 | 5 | 40.88 | 2.13 | 4.20 | 16 | 1.50 | 8.30 | 14 |

| Bahat 2015 (2) | 5 | 12 | 40.88 | 1.23 | 6.80 | 14 | 0.92 | 4.50 | 12 |

| Tompson 2016 [29] | 24 | 24 | 47.53 | 4.70 | 9.23 | 29 | -0.20 | 9.23 | 28 |

| Yilmza 2017[33] | 2 | 2 | 25.14 | 14.26 | 2.62 | 22 | 1.66 | 3.45 | 22 |

| Helminen 2015[31] | 6 | 6 | 63.64 | 2.00 | 0.57 | 55 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 56 |

| Meijer 2006 (1) [27] | 2 | 8 | 38.14 | 9.80 | 1.01 | 20 | -0.10 | 3.26 | 14 |

| Meijer 2006 (2) | 2 | 24 | 38.14 | 13.10 | 1.75 | 20 | 1.00 | 2.77 | 14 |

| Meijer 2006 (3) | 2 | 48 | 38.14 | 12.50 | 1.20 | 20 | 0.50 | 2.86 | 14 |

| Gulsen 2020 [30] | 8 | 8 | 42.50 | 14.00 | 4.65 | 8 | 7.00 | 4.30 | 8 |

The Q statistic of the meta-analysis of all included studies (equal to Chi

), T

, I

and their 95% confidence intervals and prediction intervals of the comparisons’ effect could be seen in

.

The result of heterogeneity test of all included studies.

2.4. Additional Analysis

2.4.1. Subgroup Analysis

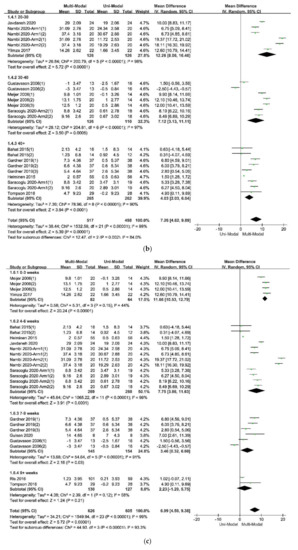

The calculation of subgroup analysis was based on the randomized effect model by RevMan5.3. According to the result of the subgroup analysis, there was a large heterogeneity within studies in subgroup analysis since the I

of each subgroup analysis was large, meaning that the different subgroups may not be the sources of the heterogeneity within the included studies, and it was necessary to do a meta-regression.

According to the characteristics of participants and design of the included studies which might affect the effectiveness of therapies, there were five subdivisions in the subgroup analysis: (1) different types of pain, which included chronic low-back pain, chronic neck pain, and non-special low-back pain; (2) different ranges of participants’ mean age which included 20 to 30, 30 to 40, and more than 40 years old; (3) different durations of treatments which included 0 to 3 weeks, 4 to 6 weeks, 7 to 9 weeks and more than 9 weeks; (4) different follow-up times which included 0 to 12 weeks, 13 to 24 weeks and more than 24 weeks; (5) different types of uni-modal interventions in control groups, which include passive physical therapy, active exercise, and only psychological education (following the hypothesis that there were different effects between passive physical therapies, active exercise, and psychological-only interventions). The indexes of heterogeneity and their 95% confidence intervals were shown in

, and all the forest plots of the subdivisions would be shown in

| Types of Pain | CLBP | 10 |

3. Discussion

In this review, the fear-avoidance model of pain was used to explain the fear of physical movement following musculoskeletal disorders, and the clinic term “Kinesiophobia” was used to define and describe fear in relation to pain. Kinesiophobia could be acquired through personal experience or social learning and could be measured by the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK). Studies used the scores of TSK-17 as one of the outcomes and compared therapies combined multi-modal from both psychological and physical perspectives with therapies in uni-modal were included in this review to summarize the evidence that might support the application of multi-modal therapies for musculoskeletal disorders and the following pain.

Although a considerable heterogeneity within the included studies, the pooled effect was positive with a statistical significance, indicating that multi-modal therapies had an advantage over uni-modal therapies. High-quality evidence reported that a long-lasting multi-modal program was superior to the exercise program in reducing disability, fear-avoidance beliefs and pain, and enhancing the quality of life of patients with different kinds of pain [15][11]. The effects were clinically tangible and lasted for at least one year after the intervention ended [15,20,22][11][16][18].

The results of the subgroup analysis in the subdivision of different types of pain, which was showed in Figure 4a indicated that the multi-modal therapies were more used in the treatments for chronic pain in the people’s trunk, especially in the neck and low back. This result was consistent with the previous fear-avoidance model about the fear of pain, which was that the experience of chronic, ongoing pain tends to become fear of pain [6,8][2][4]. What’s more, multi-modal therapies combined with physical therapies and psychological therapies had an advantage over therapies from a physical perspective, no matter the physical therapy was passive or active, as was showed in Figure 4e. Therefore, it was necessary to add psychological therapies in the treatments of chronic pain. A similar effect was found in studies that compared passive and active treatments for neck-shoulder pain and used the Visual Pain Scale (VAS) as an outcome measure [44][36]. Simultaneously, the age of participants, the duration of treatments, and the different follow-up times might affect the results. Within these factors, the participants’ age was more likely to be taken into consideration since the pooled effects showed a decreasing trend with the increase of age in Figure 4b. According to the previous study results, older people were more often had a pain of longer duration, more frequently and of more complexity, felt more disabled, received more pain treatments and had more health problems, and often used passive coping for pain [45][37]. The influence of different durations of treatments seemed unclear, as was in Figure 4c. Perhaps there were few studies comparing different durations of treatments for pain or kinesiophobia, and each treatment protocol had a different optimal duration. It might result in low homogeneity among studies and poor goodness of fit of regression equations, as shown in Table 6. At last, the pooled effects at different follow-up times seemed stale, as was in Figure 4d, indicating that the effects of multi-modal therapies might clinically tangible and lasted for a long time [15,46][11][38].

According to the meta-regression results, the covariate “follow-up times” might not be the source of the heterogeneity because that different follow-up times of included studies could hardly explain the residual variation due to between-study variance [29][39]. On the contrary, the differences of mean age of participants and the duration of treatments could explain part of the between-study variance, meaning that the two covariates might be part of the sources of the heterogeneity and would affect the effects of therapies. What’s more, the meta-regression of the mean age of participants had a significant statistical difference, showing that the effect of multi-modal therapies might decrease with age. This result might be related to the mental health and capacity of recovery of older adults [47,48][40][41]. Besides, the result of the meta-regression of the duration of treatments tended to be statistically significant. It indicated that there might be no additional benefit from increasing the duration of therapy for kinesiophobia. Finally, the goodness of fit of the model used in the meta-regression for these covariates was low, indicating that the results should be interpreted carefully.

A considerable heterogeneity within the included studies could be seen in the heterogeneity test in the meta-analysis and the subgroup analysis. The heterogeneity might come from the different designs of these studies. For example, the included studies had differences in the FITT characteristics (frequency, intensity, time, environments, and types) of the training plan [49,50][42][43]. Moreover, the different populations of the participants, the different blinding method, and some other factors, especially the different validities and reliability of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia for participants with different educational backgrounds, culture, personalities, and types of musculoskeletal disorders [26[22][23][44],27,51], might lead a heterogeneity within studies.

This review had some limitations. Firstly, few studies reported the detailed pain duration of the participants or discussed the different effects between gender, leading it infeasible to make subgroup analysis or meta-regression for these covariates. Secondly, the statistical part of some studies did not consider the test-retest reliability of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, setting the test-retest reliability as 1.00 in their analysis of variance, which was impossible in a subjective questionnaire, so that the accuracy of their results was affected. Thirdly, in the search strategy, there might be an absence of data because the scores of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia are usually reported as the secondary outcome. Finally, some studies didn’t use the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia to measure the fear of physical movements.

The risk of bias was supposed to exist, and the source is various. For example, there were many musculoskeletal disorders that could lead to a fear of physical movements. Still, not all studies in the field of physical rehabilitation reported the score of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia. In fact, to all kinds of musculoskeletal disorders with the following pain, the fear of physical movements was very common [1][1]. What’s more, different shortened versions of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, such as TSK-13 and TSK-11, were used in other studies [52[45][46],53], making these studies could not be included in the review. Lastly, other resources of publication bias could not be excluded [54,55,56,57].[47][48][49][50]

The statistical power of all pooled effect analysis in this review was larger than that in any single primary study, subgroup analysis, and the heterogeneity test. This result accords with the statistical law of meta-analysis [29][39].

References

- Turk, D.C.; Wilson, H.D. Fear of pain as a prognostic factor in chronic pain: Conceptual models, assessment, and treatment implications. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2010, 14, 88–95, doi:10.1007/s11916-010-0094-x.

- Vlaeyen, J.W.; Linton, S.J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain 2000, 85, 317–332, doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00242-0.

- Leeuw, M.; Goossens, M.E.; Linton, S.J.; Crombez, G.; Boersma, K.; Vlaeyen, J.W. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: Current state of scientific evidence. J. Behav. Med. 2007, 30, 77–94, doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9085-0.

- Vlaeyen, J.W.; Linton, S.J. Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain 2012, 153, 1144–1147, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.12.009.

- Lundberg, M.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Verbunt, J.; Simmonds, M.J. Pain-related fear: A critical review of the related measures. Pain Res. Treat. 2011, 2011, 494196, doi:10.1155/2011/494196.

- Kori S, M.R.; Todd, D.D. Kinesiophobia: A new view of chronic pain behavior. Pain Manag. 1990, 3, 35–43.

- Meier, M.L.; Stampfli, P.; Vrana, A.; Humphreys, B.K.; Seifritz, E.; Hotz-Boendermaker, S. Fear avoidance beliefs in back pain-free subjects are reflected by amygdala-cingulate responses. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 424, doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00424.

- Karos, K.; Meulders, A.; Gatzounis, R.; Seelen, H.A.M.; Geers, R.P.G.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S. Fear of pain changes movement: Motor behaviour following the acquisition of pain-related fear. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 1432–1442, doi:10.1002/ejp.1044.

- Roelofs, J.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; Goossens, M.; Thibault, P.; Boersma, K.; Vlaeyen, J.W. Fear of movement and (re)injury in chronic musculoskeletal pain: Evidence for an invariant two-factor model of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia across pain diagnoses and Dutch, Swedish, and Canadian samples. Pain 2007, 131, 181–190, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.008.

- Lundberg, M.; Larsson, M.; Ostlund, H.; Styf, J. Kinesiophobia among patients with musculoskeletal pain in primary healthcare. J. Rehabil. Med. 2006, 38, 37–43, doi:10.1080/16501970510041253.

- Monticone, M.; Ferrante, S.; Rocca, B.; Baiardi, P.; Farra, F.D.; Foti, C. Effect of a long-lasting multidisciplinary program on disability and fear-avoidance behaviors in patients with chronic low back pain: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 929–938, doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31827fef7e.

- Barnhoorn, K.J.; Staal, J.B.; van Dongen, R.T.M.; Frölke, J.P.M.; Klomp, F.P.; van de Meent, H.; Samwel, H.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G. Are pain-related fears mediators for reducing disability and pain in patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1? An explorative analysis on pain exposure physical therapy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123008, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123008.

- Wicksell, R.K.; Melin, L.; Lekander, M.; Olsson, G.L. Evaluating the effectiveness of exposure and acceptance strategies to improve functioning and quality of life in longstanding pediatric pain—A randomized controlled trial. Pain 2009, 141, 248–257, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.006.

- Valenzuela-Pascual, F.; Molina, F.; Corbi, F.; Blanco-Blanco, J.; Gil, R.M.; Soler-Gonzalez, J. The influence of a biopsychosocial educational internet-based intervention on pain, dysfunction, quality of life, and pain cognition in chronic low back pain patients in primary care: A mixed methods approach. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 97, doi:10.1186/s12911-015-0220-0.

- Klaassen, G.; Zelle, D.M.; Navis, G.J.; Dijkema, D.; Bemelman, F.J.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Corpeleijn, E. Lifestyle intervention to improve quality of life and prevent weight gain after renal transplantation: Design of the Active Care after Transplantation (ACT) randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 296, doi:10.1186/s12882-017-0709-0.

- Monticone, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Rocca, B.; Cazzaniga, D.; Liquori, V.; Pedrocchi, A.; Vernon, H. Group-based multi-modal exercises integrated with cognitive-behavioural therapy improve disability, pain and quality of life of subjects with chronic neck pain: A randomized controlled trial with one-year follow-up. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 742–752, doi:10.1177/0269215516651979.

- Monticone, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Rocca, B.; Magni, S.; Brivio, F.; Ferrante, S. A multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme improves disability, kinesiophobia and walking ability in subjects with chronic low back pain: Results of a randomised controlled pilot study. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 2105–2113, doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3478-5.

- Serrat, M.; Almirall, M.; Muste, M.; Sanabria-Mazo, J.P.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Mendez-Ulrich, J.L.; Luciano, J.V.; Sanz, A. Effectiveness of a multicomponent treatment for fibromyalgia based on pain neuroscience education, exercise therapy, psychological support, and nature exposure (NAT-FM): A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, doi:10.3390/jcm9103348.

- Cimmino, M.A.; Ferrone, C.; Cutolo, M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 25, 173–183, doi:10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.012.Malfliet, A.P.M.; Van Oosterwijck, J.P.P.; Meeus, M.P.P.; Cagnie, B.P.P.; Danneels, L.P.P.; Dolphens, M.P.P.; Buyl, R.P.P.; Nijs, J.P.P. Kinesiophobia and maladaptive coping strategies prevent improvements in pain catastrophizing following pain neuroscience education in fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome: An explorative study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2017, 33, 653–660, doi:10.1080/09593985.2017.1331481.

- Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Naghavi, M.; Lozano, R.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M.; Shibuya, K.; Salomon, J.A.; Abdalla, S.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2163–2196, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2.Trost, Z.; France, C.R.; Thomas, J.S. Examination of the photograph series of daily activities (PHODA) scale in chronic low back pain patients with high and low kinesiophobia. Pain 2009, 141, 276–282, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.016.

- Artus, M.; Campbell, P.; Mallen, C.D.; Dunn, K.M.; van der Windt, D.A. Generic prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012901, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012901.Mari, K.E.; Lundberg, J.S.; Carlsson, S.G. A psychometric evaluation of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia—From a physiotherapeutic perspective. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2004, 20, 121–133, doi:10.1080/09593980490453002.

- Keefe, F.J.; Rumble, M.E.; Scipio, C.D.; Giordano, L.A.; Perri, L.M. Psychological aspects of persistent pain: Current state of the science. J. Pain 2004, 5, 195–211, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.576.Gomez-Perez, L.; Lopez-Martinez, A.E.; Ruiz-Parraga, G.T. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK). J. Pain 2011, 12, 425–435, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2010.08.004.

- Malfliet, A.P.M.; Van Oosterwijck, J.P.P.; Meeus, M.P.P.; Cagnie, B.P.P.; Danneels, L.P.P.; Dolphens, M.P.P.; Buyl, R.P.P.; Nijs, J.P.P. Kinesiophobia and maladaptive coping strategies prevent improvements in pain catastrophizing following pain neuroscience education in fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome: An explorative study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2017, 33, 653–660, doi:10.1080/09593985.2017.1331481.Koho, P.; Aho, S.; Kautiainen, H.; Pohjolainen, T.; Hurri, H. Test-retest reliability and comparability of paper and computer questionnaires for the Finnish version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia. Physiotherapy 2014, 100, 356–362, doi:10.1016/j.physio.2013.11.007.

- Trost, Z.; France, C.R.; Thomas, J.S. Examination of the photograph series of daily activities (PHODA) scale in chronic low back pain patients with high and low kinesiophobia. Pain 2009, 141, 276–282, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.016.Gustavsson, C.; von Koch, L. Applied relaxation in the treatment of long-lasting neck pain: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2006, 38, 100–107, doi:10.1080/16501970510044025.

- Mari, K.E.; Lundberg, J.S.; Carlsson, S.G. A psychometric evaluation of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia—From a physiotherapeutic perspective. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2004, 20, 121–133, doi:10.1080/09593980490453002.Sarig Bahat, H.; Takasaki, H.; Chen, X.; Bet-Or, Y.; Treleaven, J. Cervical kinematic training with and without interactive VR training for chronic neck pain—A randomized clinical trial. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 68–78, doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.06.008.

- Gomez-Perez, L.; Lopez-Martinez, A.E.; Ruiz-Parraga, G.T. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK). J. Pain 2011, 12, 425–435, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2010.08.004.Gardner, T.; Refshauge, K.; McAuley, J.; Hübscher, M.; Goodall, S.; Smith, L. Combined education and patient-led goal setting intervention reduced chronic low back pain disability and intensity at 12 months: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1424–1431, doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100080.

- Koho, P.; Aho, S.; Kautiainen, H.; Pohjolainen, T.; Hurri, H. Test-retest reliability and comparability of paper and computer questionnaires for the Finnish version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia. Physiotherapy 2014, 100, 356–362, doi:10.1016/j.physio.2013.11.007.Meijer, E.M.; Sluiter, J.K.; Heyma, A.; Sadiraj, K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H. Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment in sick-listed patients with upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders: A randomized, controlled trial with one-year follow-up. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2006, 79, 654–664, doi:10.1007/s00420-006-0098-3.

- Gustavsson, C.; von Koch, L. Applied relaxation in the treatment of long-lasting neck pain: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2006, 38, 100–107, doi:10.1080/16501970510044025.Ris, I.; Sogaard, K.; Gram, B.; Agerbo, K.; Boyle, E.; Juul-Kristensen, B. Does a combination of physical training, specific exercises and pain education improve health-related quality of life in patients with chronic neck pain? A randomised control trial with a 4-month follow up. Man. Ther. 2016, 26, 132–140, doi:10.1016/j.math.2016.08.004.

- Sarig Bahat, H.; Takasaki, H.; Chen, X.; Bet-Or, Y.; Treleaven, J. Cervical kinematic training with and without interactive VR training for chronic neck pain—A randomized clinical trial. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 68–78, doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.06.008.Thompson, D.P.; Oldham, J.A.; Woby, S.R. Does adding cognitive-behavioural physiotherapy to exercise improve outcome in patients with chronic neck pain? A randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 170–177, doi:10.1016/j.physio.2015.04.008.

- Gardner, T.; Refshauge, K.; McAuley, J.; Hübscher, M.; Goodall, S.; Smith, L. Combined education and patient-led goal setting intervention reduced chronic low back pain disability and intensity at 12 months: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1424–1431, doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100080.Gulsen, C.; Soke, F.; Eldemir, K.; Apaydin, Y.; Ozkul, C.; Guclu-Gunduz, A.; Akcali, D.T. Effect of fully immersive virtual reality treatment combined with exercise in fibromyalgia patients: A randomized controlled trial. Assist. Technol. 2020, 1–8, doi:10.1080/10400435.2020.1772900.

- Meijer, E.M.; Sluiter, J.K.; Heyma, A.; Sadiraj, K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H. Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment in sick-listed patients with upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders: A randomized, controlled trial with one-year follow-up. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2006, 79, 654–664, doi:10.1007/s00420-006-0098-3.Helminen, E.-E.; Sinikallio, S.H.; Valjakka, A.L.; Vaisanen-Rouvali, R.H.; Arokoski, J.P.A. Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioural group intervention for knee osteoarthritis pain: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 868–881.

- Ris, I.; Sogaard, K.; Gram, B.; Agerbo, K.; Boyle, E.; Juul-Kristensen, B. Does a combination of physical training, specific exercises and pain education improve health-related quality of life in patients with chronic neck pain? A randomised control trial with a 4-month follow up. Man. Ther. 2016, 26, 132–140, doi:10.1016/j.math.2016.08.004.Saracoglu, I.; Arik, M.I.; Afsar, E.; Gokpinar, H.H. The effectiveness of pain neuroscience education combined with manual therapy and home exercise for chronic low back pain: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2020, 1–11, doi:10.1080/09593985.2020.1809046.

- Thompson, D.P.; Oldham, J.A.; Woby, S.R. Does adding cognitive-behavioural physiotherapy to exercise improve outcome in patients with chronic neck pain? A randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 170–177, doi:10.1016/j.physio.2015.04.008.Yilmaz Yelvar, G.D.; Çırak, Y.; Dalkılınç, M.; Parlak Demir, Y.; Guner, Z.; Boydak, A. Is physiotherapy integrated virtual walking effective on pain, function, and kinesiophobia in patients with non-specific low-back pain? Randomised controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 538–545, doi:10.1007/s00586-016-4892-7.

- Gulsen, C.; Soke, F.; Eldemir, K.; Apaydin, Y.; Ozkul, C.; Guclu-Gunduz, A.; Akcali, D.T. Effect of fully immersive virtual reality treatment combined with exercise in fibromyalgia patients: A randomized controlled trial. Assist. Technol. 2020, 1–8, doi:10.1080/10400435.2020.1772900.Javdaneh, N.; Letafatkar, A.; Shojaedin, S.; Hadadnezhad, M. Scapular exercise combined with cognitive functional therapy is more effective at reducing chronic neck pain and kinesiophobia than scapular exercise alone: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, doi:10.1177/0269215520941910.

- Helminen, E.-E.; Sinikallio, S.H.; Valjakka, A.L.; Vaisanen-Rouvali, R.H.; Arokoski, J.P.A. Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioural group intervention for knee osteoarthritis pain: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 868–881.Nambi, G.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Alrawaili, S.M.; Abodonya, A.M.; Saleh, A.K. Virtual reality or Isokinetic training; its effect on pain, kinesiophobia and serum stress hormones in chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Technol. Health Care Off. J. Eur. Soc. Eng. Med. 2020, doi:10.3233/THC-202301.

- Saracoglu, I.; Arik, M.I.; Afsar, E.; Gokpinar, H.H. The effectiveness of pain neuroscience education combined with manual therapy and home exercise for chronic low back pain: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2020, 1–11, doi:10.1080/09593985.2020.1809046.Savolainen, A.; Ahlberg, J.; Nummila, H.; Nissinen, M. Active or passive treatment for neck-shoulder pain in occupational health care? A randomized controlled trial. Occup. Med. 2004, 54, 422–424, doi:10.1093/occmed/kqh070.

- Yilmaz Yelvar, G.D.; Çırak, Y.; Dalkılınç, M.; Parlak Demir, Y.; Guner, Z.; Boydak, A. Is physiotherapy integrated virtual walking effective on pain, function, and kinesiophobia in patients with non-specific low-back pain? Randomised controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 538–545, doi:10.1007/s00586-016-4892-7.Soares, J.J.; Sundin, O.; Grossi, G. The stress of musculoskeletal pain: A comparison between primary care patients in various ages. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 56, 297–305, doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00078-3.

- Javdaneh, N.; Letafatkar, A.; Shojaedin, S.; Hadadnezhad, M. Scapular exercise combined with cognitive functional therapy is more effective at reducing chronic neck pain and kinesiophobia than scapular exercise alone: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, doi:10.1177/0269215520941910.Andersen, L.N.; Juul-Kristensen, B.; Sorensen, T.L.; Herborg, L.G.; Roessler, K.K.; Sogaard, K. Longer term follow-up on effects of Tailored Physical Activity or Chronic Pain Self-Management Programme on return-to-work: A randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 48, 887–892, doi:10.2340/16501977-2159.

- Nambi, G.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Alrawaili, S.M.; Abodonya, A.M.; Saleh, A.K. Virtual reality or Isokinetic training; its effect on pain, kinesiophobia and serum stress hormones in chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Technol. Health Care Off. J. Eur. Soc. Eng. Med. 2020, doi:10.3233/THC-202301.Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009.

- Rothstein, J.M. The aged and the aging of physical therapy. Phys. Ther. 1992, 72, 166–167, doi:10.1093/ptj/72.3.166.

- Gunther, R. [Special problems of physical therapy in the aged]. Z. Alternsforsch. 1986, 41, 323–330.

- Helmhout, P.H.; Harts, C.C.; Staal, J.B.; Candel, M.J.; de Bie, R.A. Comparison of a high-intensity and a low-intensity lumbar extensor training program as minimal intervention treatment in low back pain: A randomized trial. Eur. Spine J. 2004, 13, 537–547, doi:10.1007/s00586-004-0671-y.

- Heymans, M.W.; de Vet, H.C.; Bongers, P.M.; Knol, D.L.; Koes, B.W.; van Mechelen, W. The effectiveness of high-intensity versus low-intensity back schools in an occupational setting: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006, 31, 1075–1082, doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000216443.46783.4d.

- La Touche, R.; Pardo-Montero, J.; Cuenca-Martinez, F.; Visscher, C.M.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Lopez-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia for temporomandibular disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, doi:10.3390/jcm9092831.

- Steve, R.; Wobya, N.K.R.; Urmstona, M.; Watsond, P.J. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: A shortened version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia. Pain 2005, 117, 137–144, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.029.

- Neblett, R.; Hartzell, M.M.; Mayer, T.G.; Bradford, E.M.; Gatchel, R.J. Establishing clinically meaningful severity levels for the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-13). Eur. J. Pain 2016, 20, 701–710, doi:10.1002/ejp.795.

- Valiente-Castrillo, P.; Martín-Pintado-Zugasti, A.; Calvo-Lobo, C.; Beltran-Alacreu, H.; Fernández-Carnero, J. Effects of pain neuroscience education and dry needling for the management of patients with chronic myofascial neck pain: A randomized clinical trial. Acupunct. Med. J. Br. Med Acupunct. Soc. 2020, doi:10.1177/0964528420920300.

- Simister, H.D.; Tkachuk, G.A.; Shay, B.L.; Vincent, N.; Pear, J.J.; Skrabek, R.Q. Randomized controlled trial of online acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia. J. Pain 2018, 19, 741–753, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.004.

- Turner, B.J.; Liang, Y.; Rodriguez, N.; Bobadilla, R.; Simmonds, M.J.; Yin, Z. Randomized trial of a low-literacy chronic pain self-management program: Analysis of secondary pain and psychological outcome measures. J. Pain 2018, 19, 1471–1479, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.06.010.

- Miller, J.; MacDermid, J.C.; Walton, D.M.; Richardson, J. Chronic pain self-management support with pain science education and Exercise (COMMENCE) for people with chronic pain and multiple comorbidities: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 750–761, doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2019.12.016.

- Valiente-Castrillo, P.; Martín-Pintado-Zugasti, A.; Calvo-Lobo, C.; Beltran-Alacreu, H.; Fernández-Carnero, J. Effects of pain neuroscience education and dry needling for the management of patients with chronic myofascial neck pain: A randomized clinical trial. Acupunct. Med. J. Br. Med Acupunct. Soc. 2020, doi:10.1177/0964528420920300.

- Simister, H.D.; Tkachuk, G.A.; Shay, B.L.; Vincent, N.; Pear, J.J.; Skrabek, R.Q. Randomized controlled trial of online acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia. J. Pain 2018, 19, 741–753, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.004.

- Turner, B.J.; Liang, Y.; Rodriguez, N.; Bobadilla, R.; Simmonds, M.J.; Yin, Z. Randomized trial of a low-literacy chronic pain self-management program: Analysis of secondary pain and psychological outcome measures. J. Pain 2018, 19, 1471–1479, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.06.010.

- Miller, J.; MacDermid, J.C.; Walton, D.M.; Richardson, J. Chronic pain self-management support with pain science education and Exercise (COMMENCE) for people with chronic pain and multiple comorbidities: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 750–761, doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2019.12.016.