Additive manufacturing (AM, 3D printing) is used in many fields and different industries. In the medical and dental field, every patient is unique and, therefore, AM has significant potential in personalized and customized solutions. This text explores what additive manufacturing processes and materials are utilized in medical and dental applications, especially focusing on processes that are less commonly used. The processes are categorized in ISO/ASTM process classes: powder bed fusion, material extrusion, VAT photopolymerization, material jetting, binder jetting, sheet lamination and directed energy deposition combined with classification of medical applications of AM. Based on the findings, it seems that directed energy deposition is utilized rarely only in implants and sheet lamination rarely for medical models or phantoms. Powder bed fusion, material extrusion and VAT photopolymerization are utilized in all categories. Material jetting is not used for implants and biomanufacturing, and binder jetting is not utilized for tools, instruments and parts for medical devices. The most common materials are thermoplastics, photopolymers and metals such as titanium alloys. If standard terminology of AM would be followed, this would allow a more systematic review of the utilization of different AM processes. Current development in binder jetting would allow more possibilities in the future.

- additive manufacturing

- rapid manufacturing

- medical

- 3d printing

- surgery

- medical modelling

1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM), or, in a non-technical context, 3D printing, is a process where physical parts are manufactured using computer-aided design and objects are built on a layer-by-layer basis[1]. Usually, these procedures are called toolless processes. There are other processes, such as incremental sheet forming or laser forming, that build objects on a layer-by-layer basis as well but do so by adding the form, not the material [2][3]. These processes are not counted as an additive manufacturing process even though they have been similarly used in making, for example, customized medical products [4][5]. Currently, additive manufacturing is utilized and being investigated for use in areas such as the medical, automotive, aerospace and marine industries, as well as industrial spare parts [6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]. It has also started to have an important role in engineering education[14]. Additive manufacturing is referred to as a manufacturing method where complexity or customization is free[15]. However, this requires marking and tracing of the different parts compared to mass production of the same kind of parts and building orientation affects parts cost and building times[16]. Nevertheless, when comparing AM against conventional manufacturing, it has a much higher potential for customization and complex geometries. However, when comparing cost, additive manufacturing is usually not cheaper if the geometry is designed for mass production and only the manufacturing cost is calculated[17]. It would suffice to reiterate the whole product design and look at the economics over the entire product lifecycle[18]. AM is currently developing fast, and new players are entering the market all the time. There have been substantial investments in new companies, such as Carbon, Desktop Metal and Formlabs, as well as internal development in large companies in other areas, such as HP and GE. Even though the basic principles of the different AM processes have stayed the same, there are now more development resources to take the next step forward for these technologies, and this will also open up new possibilities in medical applications[19][20][21][22].

In the medical field, every patient is unique, and therefore, AM has a high potential to be utilized for personalized and customized medical applications. The most common medical clinical uses are personalized implants, medical models and saw guides[23]. In the dental field, AM is utilized on splints, orthodontic appliances, dental models and drill guides. However, AM has also been explored for making artificial tissues and organs[24]. In medicine, there is a background in digitalization of medical imaging, and that digitalization allows for reconstructing 3D models from patients’ anatomy. A typical workflow for personalized medical devices starts with imaging or capturing the patient’s geometry using computed tomography or other 3D scanning methods[25]. Then, these data are manipulated to obtain a 3D model of the patient’s anatomy, and this can be an example already of additive manufacturing such as a medical model. Moreover, the geometry can be utilized to design patient-specific implants, and this design can be additively manufactured. After manufacturing, there is quite often a need for post-processing, such as polishing[26]. When the medical device is ready, the final step is the clinical application and follow-up.

The usage of AM is usually related to the question of what the benefits are compared to existing processes and technologies. Most often, the questions are related to whether it is cheaper to manufacture, but the whole lifecycle of the product and process should be investigated. The actual manufacturing prices cannot be the only performance indicator. Table 1 summarizes some of the benefits of AM in the medical and dental fields. Quite often, similar benefits can be found in other subject areas than medical and dental fields, for example, the industrial side, such as digital storage for industrial spare parts, which reflects heavily to digital storage of dental data.

Table 1.

Some of the benefits of additive manufacturing (AM) in medical and dental fields.

| Reference | Findings | Area | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballard et al. | [27] | cost and time savings | Orthopedic and maxillofacial surgery |

| Choonora et al. | [28] | personalization | Transplants |

| Mahmoud et al. | [29] | cost savings | Pathology specimens for students |

| Tack et al. | [30] | time savings, improved medical outcome, decreased radiation exposure | Surgery |

| Ballard et al. | [31] | incorporation of antibiotics | Implants |

| Lin et al. | [32] | personalization, cost savings | Dental |

| Javaid et al. | [33] | cost and time savings, personalization, digital storage | Dental |

| Aho et al. | [34] | personalization | Pharmacy |

| Salmi et al. | [35] | reduction of manual work | Dental appliances |

| Aquino et al. | [36] | personalization, on-demand manufacturing | Pharmacy |

| Javaid et al. | [37] | accuracy, cost and time savings, personalization, fully automated and digitized manufacturing | Orthopedics |

| Emelogu et al. | [38] | supply chain possibilities | Implants |

| [ | |||

| 44 | |||

| ] | |||

| improved understanding of anatomy and accuracy of surgery | |||

| Surgery |

Since AM is a class of manufacturing processes, it is important to understand what the bases of these processes are, how those differ from each other and to describe how the process works.

2. Additive Manufacturing Processes

The ASTM and ISO standardization organization categorizes the AM process into seven different categories: powder bed fusion (PBF), material extrusion (ME), VAT photopolymerization (VP), material jetting (MJ), binder jetting (BJ), sheet lamination (SL) and directed energy deposition (DED)[1]. Each category includes many different vendors, solutions and material options. In this article, ASTM/ISO categories were followed. This was problematic, since the standard terminology is still not utilized in most studies, and often trade names are used for processes. To clarify different processes and principles, Table 2 lists the names of the process classes and a short description, common starting material form, trade names and how well the process is used to manufacture the plastic type of materials, metals or ceramics. Some of the processes for certain materials are in the development and research phase, such as directed energy deposition VAT photopolymerization and material jetting for metals, and some seem not to exist at all, such as sheet lamination of ceramics or directed energy deposition of plastics and ceramics. It is possible that there are scientific studies and trials of these, but no commercial providers exist. Commonly, new process and material combinations are developed based on demand, which highlights large industries and a substantial need. Usually, this leads to the selection of a commonly used material since that can be utilized in many areas.

Table 2.

Characteristics of different AM processes.

| AM Process | Short Description | Material Form | Plastics | Metals | Ceramics | Trade/Other Names |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powder bed fusion (PBF) | thermal energy fuses regions of a powder bed | powder | +++ | +++ | + | selective laser sintering (SLS), direct metal laser sintering (DMLS), selective laser melting (SLM) |

| Material extrusion (MEX) | material dispensed through a nozzle | filament, pellets, paste | +++ | ++ | ++ | fused deposition modeling (FDM), (fused filament fabrication) FFF |

| VAT photo-polymerization (VP) | liquid photopolymer in a vat is cured by light | liquid | +++ | + | ++ | SLA, digital light projection (DLP) |

| Material jetting (MJ) | droplets of material are selectively deposited | liquid | +++ | + | + | PolyJet, NJP |

| Binder jetting (BJ) | a liquid bonding agent is selectively deposited | powder | +++ | ++ | + | 3D printing (3DP), ColorJet printing (CJP) |

| Sheet lamination (SL) | sheets of material are bonded | sheets | ++ | ++ | - | laminated object manufacturing (LOM), ultrasonic additive manufacturing (UAM) |

| Directed energy deposition (DED) | focused thermal energy used to fuse materials by melting when depositing | powder, wire | - | +++ | + | laser-engineered net shaping (LENS), EBAM |

| Gibson et al. | ||||||

| [ | ||||||

| 10 | ||||||

| ] | ||||||

| surgeon as a designer, innovation potential | Surgery | |||||

| Haleem et al. | [39] | ability to use different materials | Medical | |||

| Murr et al. | [40] | ability to make complex geometries | Implants | |||

| Peltola et al. | [41] | template for forming implants | Implants | |||

| Ramakrishnaiah et al. | [42] | rough and porous surface texture, better stabilization and osseointegration | Dental implants | |||

| Nazir et al. | [43] | design iterations, supply chain possibilities, complex geometries | Medical devices | |||

| Yang et al. |

Note: +++, widely available/many studies exist; ++, available/several studies exist; +, R&D phase/studies exist; -, no studies exist.

Each AM process and piece of equipment require a 3D model of the object that they will manufacture, and the most used format for that is stereolithography, standard triangle language, standard tessellation language (STL). The STL model is then sliced into layers and further processed to commands for the specific AM machine. To additively manufacture the part, a raw material is required, such as power, filament, liquid, paste sheet or pellets. The raw material can then be, for example, melted, dispensed, cured or fused to make parts on a layer-by-layer basis. Terminology in AM varies and, as an example, the powder bed fusion process can be called selective laser melting (SLM), selective laser sintering (SLS) or direct metal laser sintering (DMLS). For material extrusion, the most used terms are fused deposition modeling (FDM) or fused filament fabrication (FFF). As a first invented AM process, stereolithography (SLA) has been very commonly used for processes in the VAT photopolymerization class, but digital light projection (DLP) is also used if the light source is a DPL projector. Trade names in material jetting are PolyJet and NanoParticle Jetting. Binder jetting is often called 3D printing (3DP) or ColorJet printing (CJP). Sheet lamination processes are laminated object manufacturing (LOM) and ultrasonic additive manufacturing (UAM). Directed energy deposition processes are laser-engineered net shaping (LENS) and electron beam additive manufacturing. In addition, many others exist on the market.

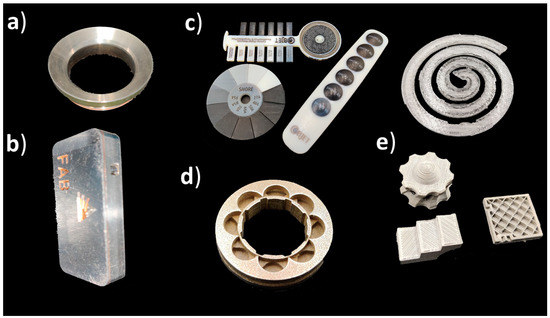

3. Medical Applications of Additive Manufacturing

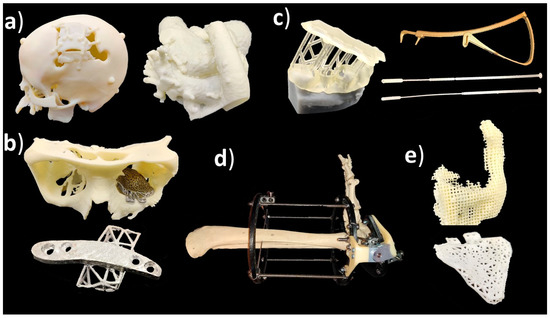

Medical applications of additive manufacturing can be classified in several ways [45][46], but this article follows application classes-based classification. AM applications can be classified into the following classes: “models for preoperative planning, education and training”, “inert implants”, “tools, instruments and parts for medical devices”, “medical aids, supportive guides, splints and prostheses” and “biomanufacturing”[47]. For a more general classification, this can be modified so that implants do not need to be inert, and models for preoperative planning, education and training could also include postoperative and operative models using the term “medical models”. Figure 1 shows an example of an application in each category including a (a) preoperative model of a skull and heart, (b) craniomaxillofacial implants, (c) a dental drilling guide, reduction forceps, nasal and throat swabs, (d) personalized and mobilizing external support and (e) a scaffold for zygomatic bone replacement and resorbable orbital implants.

Figure 1. (a) Medical models; (b) implants; (c) tools, instruments and parts for medical devices; (d) medical aids, supportive guides, splints and prostheses; (e) biomanufacturing.

Classification of medical applications of additive manufacturing[48]:

-

Medical models;

-

Implants;

-

Tools, instruments and parts for medical devices;

-

Medical aids, supportive guides, splints and prostheses;

-

Biomanufacturing.

3.1. Medical Models

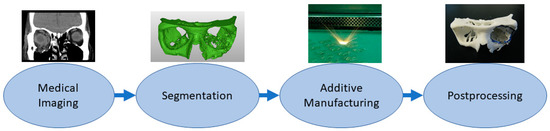

Medical models are based on patient anatomy, and they can be used for pre- and postoperative operative planning and training; training medical students; and informing patients and patients’ families[30][49]. The geometry can be transformed, for example, by taking only interesting sections or scaling it up or down. If models are used for training, such as bone drilling, haptic response might be desirable to be close to the bone. Medical models are widely used in the craniomaxillofacial area, but there are also cases, for example, from different limbs and other bone structures such as the spine and pelvis[30][50]. If these are utilized in the operating theater, it might be recommended that the models be sterilized, but usually, the material option can be quite freely selected which highlights also that these are one of the most common applications. Figure 2 shows a typical process workflow for manufacturing medical models starting from patient anatomy captured via medical imaging, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound, followed by constructing a 3D model geometry for AM using segmentation algorithms [51][52]. After AM, there is often a need for postprocessing such as removing the support structures.

Figure 2. Typical process flow for medical models.

3.2. Implants

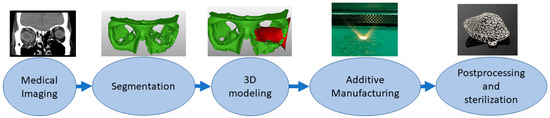

Implants are directly or indirectly additively manufactured to replace defective or missing tissue [53][54]. This class also includes dental applications such as crowns and bridges[55]. The material needs to be tissue-compatible and requirements are strict, and approval processes take a long time. Surface properties might affect cell adhesion. Some of the latest studies have explored how to embed materials inside implants, for example, as a type of drug delivery system [56][57]. In personalized implants, AM is a favorable solution, and a typical process requires the capture of a patient’s anatomy similar to medical models. Then, this digital 3D model of the patient anatomy is used as a design reference to enable patient-specific fitting [58][59]. Most typical implants are made from metals using the powder bed fusion process, and this requires different postprocessing steps such as machining the supports, polishing and heat treatments. Before clinical operation, implants need to be sterilized. Figure 3 shows the typical process flow for implants made by additive manufacturing starting from medical imaging and segmentation followed by 3D modeling of the implant proceeding to AM, postprocessing and sterilization.

Figure 3. Typical process flow for implants.

3.3. Tools, Instruments and Parts for Medical Devices

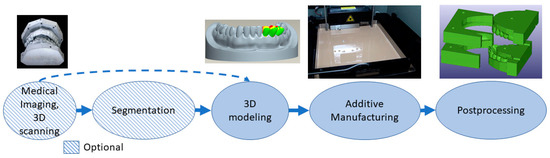

Tools, instruments and parts for medical devices allow or enhance a clinical operation. They might utilize patient-specific dimensions and shapes, for example, in drilling guides [60], and can be invasive and need a sterilization process, since they can be in contact with body fluids, membranes, tissues and organs for a limited time. This class includes surgical instruments and orthodontic appliances [61][62][63]. One of the largest and most successful businesses in this class is using the VAT photopolymerization process to create molds for vacuum forming clear orthodontic aligners[64]. When patient-specific dimensions are utilized, the process is similar to that of implants and preoperative models from medical imaging or 3D scanning. 3D modeling can be conducted by referring to the 3D model of the patient’s anatomy or from scratch if a patient-specific geometry or fitting is not needed. Postprocessing might include support removal, heat treatments, machining and sterilization. Tools, instruments and parts for medical devices are typically made with the process flow shown in Figure 4. For example, the process starts by taking an impression of the patient’s teeth, 3D scanning it, followed by 3D modeling, VAT photopolymerization AM, postprocessing and using the part made as a mold for soft orthodontic aligners.

Figure 4.

Typical process flow for tools, instruments and parts for medical devices.

3.4. Medical Aids, Supportive Guides, Splints and Prostheses

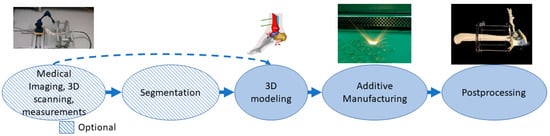

In this class, parts made with additive manufacturing are external to the body, and these can be combined with standard appliances to allow customization. Long-term and postoperative supports, motion guides, fixators, external prostheses, prosthesis sockets, personalized splints and orthopedic applications are examples of applications in this class [65][66][67][68]. The process can start from medical imaging followed by segmentation, 3D scanning or 3D measurements that can provide data directly for use in the 3D modeling phase. Alternative manufacturing methods for additive manufacturing are quite often computer numerical control (CNC) technologies[69]. Parts may require different kinds of postprocessing depending on the application such as support removal, heat treatments and painting or coating. The typical process flow for medical aids, supportive guides, splints and prostheses using AM is presented in Figure 5. The example case is a personalized and mobilizing external support for a pilon fracture, where 3D modeling is based on measuring the patient’s ankle movement and adjusting the additive manufacturing pieces to locate the hinge so that it controls the movement under force close to the free movement of the ankle.

Figure 5.

The typical process flow for medical aids, supportive guides, splints and prostheses.

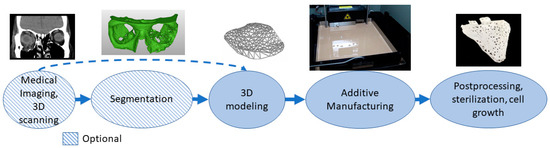

3.5. Biomanufacturing

Biomanufacturing is a combination of additive manufacturing and tissue engineering [70]. Materials need to be biologically compatible and often active with the body so many different polymers, ceramics and composite materials are used[71]. Porous structures with cultivation and a 3D matrix can affect cell specialization. The materials can be osteoinductive, osteoconductive or resorbable[72]. Shapes can be personalized to correspond to defects[73]. For personalized shapes, the patient’s geometry needs to be captured using medical imaging or 3D scanning. In the 3D modeling phase, micro- and macrostructures are modeled, and porous structures are often used for attracting cells and cell growth. The process often needs to be sterile or parts made with the ability to be sterilized after printing. Before final application, there might also be the need for cell growth in vitro or in vivo. Figure 6 shows an example of an orbital floor resorbable implant stating patient geometry with CT and segmentation followed by 3D modeling and AM of the implant. After manufacturing, the implant is sterilized.

Figure 6. Typical process flow for biomanufacturing.

There are previous studies regarding certain processes and/or application areas of medical applications of AM such as powder bed fusion of metal implants

[74]

, additive manufacturing of medical instruments

[61]

, biomaterials in medical additive manufacturing

[75]

and medical phantoms and regenerated tissue and organ applications with additive manufacturing

[76]

. Previous studies have not usually classified the AM processes or reviewed only a single process. Some studies focused only on utilized material

[77]

s and some only on applications without any information about the AM processes or materials. Based on findings from the literature,

shows the different AM processes and materials used or explored in the medical application classes formed.

Table 3.

| Application Area | PBF | MEX | VP | MJ | BJ | SL | DED | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical models | [78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][50][56] | PA, PP | ABS+, PLA | Photocurable resin | VeroWhite, VeroClear, TangoPlus, Multi-material | ZP150, ZP151, PMMA | Paper | |

| Implants | [42][88][56][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98] | Ti6Al4VTi64, Co–Cr–Mo, Al2O3–ZrO2 | PEEK | Clear resin V4, ATZ, NextDent C&B | ZP150, TCP, nickel-based alloy 625, Titanium | Ti6Al4V | ||

| Tools, instruments and parts for medical devices | [60][99][62][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107] | PA, Co–Cr, Ti | ABS, ABS+, PLA, | ProtoGen O-XT 18420, Dental SG, Dental LT, Clear resin V2, Photocurable resin WaterShed XC 11122 | TangoPlus, HeartPrint Flex, MED610 | Paper | ||

| Medical aids, supportive guides, splints and prostheses | [66][67][108][109][110][111][112] | PA | ABS, PLA, Nylon | Clear resin, Ciba–Geigy 5170, Somos 6110, Epoxy | Multi-material, Full Cure 720, ABS like, VeroWhite | ZP151, Stainless steel | ||

| Biomanufacturing | [70][113][114][115][116][117][118] | PLA, PLGA | PCL, PLA, PLGA, TCP | PDLLA, HA | VisiJet PXL, Calcium phosphate, barium titanate |

Note: polyamide (PA), polypropylene (PP), polyether ether ketone (PEEK), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), polylactic acid (PLA), poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), tricalcium phosphate (TCP), alumina toughened zirconia (ATZ), poly(DL-lactic acid) (PDLLA), hydroxyapatite (HA), Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA).

3.6. Processes Utilized Rarely—DED, SL

Processes Utilized Rarely—DED, SL

[119]

[121]

[122]

3.7. Well Established Processes—PBF, MEX, VP

5.3. Well Established Processes—PBF, MEX, VP

3.8. Processes Well Established in Some Application Areas—MJ, BJ

5.4. Processes Well Established in Some Application Areas—MJ, BJ

[128]

[130]

[131]

3.9. Future Possibilities

5.5. Future Possibilities

[132]

Figure 7.

a

b

c

d

e

-

Directed energy deposition—repairing medical parts especially in tools, instruments and parts for medical devices;

-

Sheet lamination—multi-metal parts in medicine, especially in tools, instruments and parts for medical devices;

-

Material extrusion—composite parts and multi-material, especially in medical aids, supportive guides, splints and prostheses;

-

Material extrusion—metal parts especially in implants and tools, instruments and parts for medical devices;

-

Binder jetting—metal parts especially in implants and tools, instruments and parts for medical devices;

-

Material jetting—multi-material parts, especially in medical models and biomanufacturing.

References

- ASTM International. ISO/ASTM52900—15 Standard Terminology for Additive Manufacturing—General Principles—Terminology; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Lehtinen, P.; Väisänen, T.; Salmi, M. The effect of local heating by laser irradiation for aluminum, deep drawing steel and copper sheets in incremental sheet forming. Phys. Procedia 2015, 78, 312–319.

- Casalino, G.; Ludovico, A.D.; Ancona, A.; Lugarà, P.M. Stainless Steel 3D Laser Forming for Rapid Prototyping. In International Congress on Applications of Lasers & Electro-Optics; Laser Institute of America: Orlando, FL, USA, 2001; Volume 2001, pp. 808–816.

- Ambrogio, G.; De Napoli, L.; Filice, L.; Gagliardi, F.; Muzzupappa, M. Application of Incremental Forming process for high customised medical product manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2005, 162, 156–162.

- Eksteen, P.D.; Van der Merwe, A.F. Incremental sheet forming (ISF) in the manufacturing of titanium based plate implants in the bio-medical sector. In Proceedings of the 42nd Computers and Industrial Engineering, Cape Town, South Africa, 16–18 July 2012; pp. 15–18.

- Calle, M.A.; Salmi, M.; Mazzariol, L.M.; Alves, M.; Kujala, P. Additive manufacturing of miniature marine structures for crashworthiness verification: Scaling technique and experimental tests. Mar. Struct. 2020, 72, 102764.

- Kestilä, A.; Nordling, K.; Miikkulainen, V.; Kaipio, M.; Tikka, T.; Salmi, M.; Auer, A.; Leskelä, M.; Ritala, M. Towards space-grade 3D-printed, ALD-coated small satellite propulsion components for fluidics. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 22, 31–37.

- Delic, M.; Eyers, D.R. The effect of additive manufacturing adoption on supply chain flexibility and performance: An empirical analysis from the automotive industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107689.

- Kretzschmar, N.; Chekurov, S.; Salmi, M.; Tuomi, J. Evaluating the readiness level of additively manufactured digital spare parts: An industrial perspective. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1837.

- Gibson, I.; Srinath, A. Simplifying medical additive manufacturing: Making the surgeon the designer. Procedia Technol. 2015, 20, 237–242.

- Salmi, M., Partanen, J., Tuomi, J., Chekurov, S., Björkstrand, R., Huotilainen, E., et al. (2018). DigitalSpare Parts. Aalto University and VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland.http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-60-3746-2

- Chekurov, S., & Salmi, M. (2017). Additive manufacturing in offsite repair of consumer electronics. Physics Procedia, 89, 23-30.

- Calle, M. A., Salmi, M., Mazzariol, L. M., & Kujala, P. (2020). Miniature reproduction of raking tests on marine structure: Similarity technique and experiment. Engineering Structures, 212, 110527.

- Chekurov, S., Wang, M., Salmi, M., & Partanen, J. (2020). Development, Implementation, and Assessment of a Creative Additive Manufacturing Design Assignment: Interpreting Improvements in Student Performance. Education Sciences, 10(6), 156.

- Conner, B.P.; Manogharan, G.P.; Martof, A.N.; Rodomsky, L.M.; Rodomsky, C.M.; Jordan, D.C.; Limperos, J.W. Making sense of 3-D printing: Creating a map of additive manufacturing products and services. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1, 64–76.

- Salmi, M., Ituarte, I. F., Chekurov, S., & Huotilainen, E. (2016). Effect of build orientation in 3D printing production for material extrusion, material jetting, binder jetting, sheet object lamination, vat photopolymerisation, and powder bed fusion. International Journal of Collaborative Enterprise, 5(3-4), 218-231.

- Baumers, M.; Dickens, P.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. The cost of additive manufacturing: Machine productivity, economies of scale and technology-push. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 102, 193–201.

- Thomas, D.S.; Gilbert, S.W. Costs and cost effectiveness of additive manufacturing. Nist Spec. Publ. 2014, 1176, 12.

- Van Noort, R. The future of dental devices is digital. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 3–12.

- Jockusch, J.; Özcan, M. Additive manufacturing of dental polymers: An overview on processes, materials and applications. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 345–354.

- Ghomi, E.R.; Khosravi, F.; Neisiany, R.E.; Singh, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Future of Additive Manufacturing in Healthcare. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 17, 100255.

- Singh, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Biomedical applications of additive manufacturing: Present and future. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 2, 105–115.

- Pettersson, A.; Salmi, M.; Vallittu, P.; Serlo, W.; Tuomi, J.; Mäkitie, A.A. Main Clinical Use of Additive Manufacturing (Three-Dimensional Printing) in Finland Restricted to the Head and Neck Area in 2016–2017. Scand. J. Surg. 2020, 109, 166–173.

- Zadpoor, A.A.; Malda, J. Additive Manufacturing of Biomaterials, Tissues, and Organs. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 1, 1–11.

- Bibb, R.; Eggbeer, D.; Paterson, A. Medical Modelling: The Application of Advanced Design and Development Techniques in Medicine; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2006.

- Kumbhar, N.N.; Mulay, A.V. Post processing methods used to improve surface finish of products which are manufactured by additive manufacturing technologies: A review. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. C 2018, 99, 481–487.

- Ballard, D.H.; Mills, P.; Duszak, R., Jr.; Weisman, J.A.; Rybicki, F.J.; Woodard, P.K. Medical 3D printing cost-Savings in Orthopedic and Maxillofacial Surgery: Cost analysis of operating room time saved with 3D printed anatomic models and surgical guides. Acad. Radiol. 2020, 27, 1103–1113.

- Choonara, Y.E.; du Toit, L.C.; Kumar, P.; Kondiah, P.P.; Pillay, V. 3D-printing and the effect on medical costs: A new era? Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2016, 16, 23–32.

- Mahmoud, A.; Bennett, M. Introducing 3-dimensional printing of a human anatomic pathology specimen: Potential benefits for undergraduate and postgraduate education and anatomic pathology practice. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2015, 139, 1048–1051.

- Tack, P.; Victor, J.; Gemmel, P.; Annemans, L. 3D-printing techniques in a medical setting: A systematic literature review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 115.

- Ballard, D.H.; Tappa, K.; Boyer, C.J.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Hemmanur, K.; Weisman, J.A.; Alexander, J.S.; Mills, D.K.; Woodard, P.K. Antibiotics in 3D-printed implants, instruments and materials: Benefits, challenges and future directions. J. 3d Print. Med. 2019, 3, 83–93.

- Lin, L.; Fang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, G.; Gao, C.; Zhu, P. 3D printing and digital processing techniques in dentistry: A review of literature. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1801013.

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A. Current status and applications of additive manufacturing in dentistry: A literature-based review. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2019, 9, 179–185.

- Aho, J.; Bøtker, J.P.; Genina, N.; Edinger, M.; Arnfast, L.; Rantanen, J. Roadmap to 3D-printed oral pharmaceutical dosage forms: Feedstock filament properties and characterization for fused deposition modeling. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 26–35.

- Salmi, M.; Paloheimo, K.; Tuomi, J.; Ingman, T.; Mäkitie, A. A digital process for additive manufacturing of occlusal splints: A clinical pilot study. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20130203.

- Aquino, R.P.; Barile, S.; Grasso, A.; Saviano, M. Envisioning smart and sustainable healthcare: 3D Printing technologies for personalized medication. Futures 2018, 103, 35–50.

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A. Current status and challenges of Additive manufacturing in orthopaedics: An overview. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 10, 380–386.

- Emelogu, A.; Marufuzzaman, M.; Thompson, S.M.; Shamsaei, N.; Bian, L. Additive manufacturing of biomedical implants: A feasibility assessment via supply-chain cost analysis. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 11, 97–113.

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M. 3D printed medical parts with different materials using additive manufacturing. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 215–223.

- Murr, L.E.; Gaytan, S.M.; Medina, F.; Lopez, H.; Martinez, E.; Machado, B.I.; Hernandez, D.H.; Martinez, L.; Lopez, M.I.; Wicker, R.B. Next-generation biomedical implants using additive manufacturing of complex, cellular and functional mesh arrays. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 368, 1999–2032.

- Peltola, M.J.; Vallittu, P.K.; Vuorinen, V.; Aho, A.A.; Puntala, A.; Aitasalo, K.M. Novel composite implant in craniofacial bone reconstruction. Eur. Arch. Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2012, 269, 623–628.

- Ramakrishnaiah, R.; Mohammad, A.; Divakar, D.D.; Kotha, S.B.; Celur, S.L.; Hashem, M.I.; Vallittu, P.K.; Rehman, I.U. Preliminary fabrication and characterization of electron beam melted Ti–6Al–4V customized dental implant. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 787–796.

- Nazir, A.; Azhar, A.; Nazir, U.; Liu, Y.; Qureshi, W.S.; Chen, J.; Alanazi, E. The rise of 3D Printing entangled with smart computer aided design during COVID-19 era. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020.

- Yang, T.; Lin, S.; Xie, Q.; Ouyang, W.; Tan, T.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Pan, J. Impact of 3D printing technology on the comprehension of surgical liver anatomy. Surg. Endosc. 2019, 33, 411–417.

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A. Additive manufacturing applications in medical cases: A literature based review. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 411–422.

- Tuomi, J.; Paloheimo, K.; Vehviläinen, J.; Björkstrand, R.; Salmi, M.; Huotilainen, E.; Kontio, R.; Rouse, S.; Gibson, I.; Mäkitie, A.A. A novel classification and online platform for planning and documentation of medical applications of additive manufacturing. Surg. Innov. 2014, 21, 553–559.

- Tuomi, J.; Paloheimo, K.; Björkstrand, R.; Salmi, M.; Paloheimo, M.; Mäkitie, A.A. Medical applications of rapid prototyping—From applications to classification. In Innovative Developments in Design and Manufacturing—Advanced Research in Virtual and Rapid Prototyping; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 701–704.

- Salmi, M. Additive Manufacturing Processes in Medical Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 191.

- Ventola, C.L. Medical applications for 3D printing: Current and projected uses. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 704.

- Salmi, M. Possibilities of preoperative medical models made by 3D printing or additive manufacturing. J. Med. Eng. 2016, 2016, 6191526.

- Bücking, T.M.; Hill, E.R.; Robertson, J.L.; Maneas, E.; Plumb, A.A.; Nikitichev, D.I. From medical imaging data to 3D printed anatomical models. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178540.

- Marro, A.; Bandukwala, T.; Mak, W. Three-dimensional printing and medical imaging: A review of the methods and applications. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2016, 45, 2–9.

- Salmi, M.; Tuomi, J.; Paloheimo, K.; Paloheimo, M.; Björkstrand, R.; Mäkitie, A.A.; Mesimäki, K.; Kontio, R. Digital design and rapid manufacturing in orbital wall reconstruction. In Innovative Developments in Design and Manufacturing—Advanced Research in Virtual and Rapid Prototyping; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 339–342.

- Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhou, S.; Xu, W.; Leary, M.; Choong, P.; Qian, M.; Brandt, M.; Xie, Y.M. Topological design and additive manufacturing of porous metals for bone scaffolds and orthopaedic implants: A review. Biomaterials 2016, 83, 127–141.

- Tahayeri, A.; Morgan, M.; Fugolin, A.P.; Bompolaki, D.; Athirasala, A.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Ferracane, J.L.; Bertassoni, L.E. 3D printed versus conventionally cured provisional crown and bridge dental materials. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 192–200.

- Akmal, J.S.; Salmi, M.; Mäkitie, A.; Björkstrand, R.; Partanen, J. Implementation of industrial additive manufacturing: Intelligent implants and drug delivery systems. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 41.

- Prasad, L.K.; Smyth, H. 3D Printing technologies for drug delivery: A review. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2016, 42, 1019–1031.

- Hieu, L.C.; Bohez, E.; Vander Sloten, J.; Phien, H.N.; Esichaikul, V.; Binh, P.H.; An, P.V.; To, N.C.; Oris, P. Design and manufacturing of personalized implants and standardized templates for cranioplasty applications. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology, IEEE ICIT’02, Bankok, Thailand, 11–14 December 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 1025–1030.

- Hieu, L.C.; Bohez, E.; Vander Sloten, J.; Phien, H.N.; Vatcharaporn, E.; Binh, P.H.; An, P.V.; Oris, P. Design for medical rapid prototyping of cranioplasty implants. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2003, 9, 175–186.

- Liu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Quan, X.; Zhao, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y. Preliminary application of a multi-level 3D printing drill guide template for pedicle screw placement in severe and rigid scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 1684–1689.

- Culmone, C.; Smit, G.; Breedveld, P. Additive manufacturing of medical instruments: A state-of-the-art review. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 461–473.

- Kontio, R.; Björkstrand, R.; Salmi, M.; Paloheimo, M.; Paloheimo, K.S.; Tuomi, J.; Mäkitie, A. Designing and additive manufacturing a prototype for a novel instrument for mandible fracture reduction. Surgery 2012, S1, 1–3.

- Chin, S.; Wilde, F.; Neuhaus, M.; Schramm, A.; Gellrich, N.; Rana, M. Accuracy of virtual surgical planning of orthognathic surgery with aid of CAD/CAM fabricated surgical splint—A novel 3D analyzing algorithm. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 1962–1970.

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B. Direct digital manufacturing. In Additive Manufacturing Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 375–397.

- Herbert, N.; Simpson, D.; Spence, W.D.; Ion, W. A preliminary investigation into the development of 3-D printing of prosthetic sockets. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2005, 42, 141.

- Ten Kate, J.; Smit, G.; Breedveld, P. 3D-printed upper limb prostheses: A review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 12, 300–314.

- Paterson, A.M.; Donnison, E.; Bibb, R.J.; Ian Campbell, R. Computer-aided design to support fabrication of wrist splints using 3D printing: A feasibility study. Hand Ther. 2014, 19, 102–113.

- Lindahl, J. E., Salo, J., Tuomi, J., Björkstrand, R., Salmi, M., Huotilainen, E., & Roiha, M. (2017). U.S. Patent No. 9,737,336. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Rosicky, J.; Grygar, A.; Chapcak, P.; Bouma, T.; Rosicky, J. Application of 3D scanning in prosthetic & orthotic clinical practice. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on 3D Body Scanning Technologies, Lugano, Switzerland, 30 November–1 December 2016; pp. 88–97.

- Bártolo, P.J.; Chua, C.K.; Almeida, H.A.; Chou, S.M.; Lim, A. Biomanufacturing for tissue engineering: Present and future trends. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2009, 4, 203–216.

- Bidanda, B.; Bártolo, P.J. Virtual Prototyping & Bio Manufacturing in Medical Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007.

- Danna, N.R.; Leucht, P. Designing Resorbable Scaffolds for Bone Defects. Bull. Nyu Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2019, 77, 39–44.

- Zadpoor, A.A. Design for additive bio-manufacturing: From patient-specific medical devices to rationally designed meta-biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1607.

- Lowther, M.; Louth, S.; Davey, A.; Hussain, A.; Ginestra, P.; Carter, L.; Eisenstein, N.; Grover, L.; Cox, S. Clinical, industrial, and research perspectives on powder bed fusion additively manufactured metal implants. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 565–584.

- Tappa, K.; Jammalamadaka, U. Novel biomaterials used in medical 3D printing techniques. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 17.

- Wang, K.; Ho, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B. A review on the 3D printing of functional structures for medical phantoms and regenerated tissue and organ applications. Engineering 2017, 3, 653–662.

- Salmi, M.; Tuomi, J.; Paloheimo, K.; Paloheimo, M.; Björkstrand, R.; Mäkitie, A.A.; Mesimäki, K.; Kontio, R. Digital design and rapid manufacturing in orbital wall reconstruction. In Innovative Developments in Design and Manufacturing—Advanced Research in Virtual and Rapid Prototyping; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 339–342.

- Alku, P.; Murtola, T.; Malinen, J.; Kuortti, J.; Story, B.; Airaksinen, M.; Salmi, M.; Vilkman, E.; Geneid, A. OPENGLOT–An open environment for the evaluation of glottal inverse filtering. Speech Commun. 2019, 107, 38–47.

- Mäkitie, A.A.; Salmi, M.; Lindford, A.; Tuomi, J.; Lassus, P. Three-dimensional printing for restoration of the donor face: A new digital technique tested and used in the first facial allotransplantation patient in Finland. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 69, 1648–1652.

- Szymor, P.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Olszewski, R. Accuracy of open-source software segmentation and paper-based printed three-dimensional models. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 44, 202–209.

- Mäkitie, A.; Paloheimo, K.S.; Björkstrand, R.; Salmi, M.; Kontio, R.; Salo, J.; Yan, Y.; Paloheimo, M.; Tuomi, J. Medical applications of rapid prototyping--three-dimensional bodies for planning and implementation of treatment and for tissue replacement. Duodecim 2010, 126, 143–151.

- Salmi, M.; Paloheimo, K.; Tuomi, J.; Wolff, J.; Mäkitie, A. Accuracy of medical models made by additive manufacturing (rapid manufacturing). J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 41, 603–609.

- Ionita, C.N.; Mokin, M.; Varble, N.; Bednarek, D.R.; Xiang, J.; Snyder, K.V.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Levy, E.I.; Meng, H.; Rudin, S. Challenges and limitations of patient-specific vascular phantom fabrication using 3D Polyjet printing. In Medical Imaging 2014: Biomedical Applications in Molecular, Structural, and Functional Imaging; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume 9038, p. 90380M.

- Aitasalo, K.M.; Piitulainen, J.M.; Rekola, J.; Vallittu, P.K. Craniofacial bone reconstruction with bioactive fiber-reinforced composite implant. Head Neck 2014, 36, 722–728.

- Bergstroem, J.S.; Hayman, D. An overview of mechanical properties and material modeling of polylactide (PLA) for medical applications. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 330–340.

- Panesar, S.S.; Magnetta, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Abhinav, K.; Branstetter, B.F.; Gardner, P.A.; Iv, M.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C. Patient-specific 3-dimensionally printed models for neurosurgical planning and education. Neurosurg. Focus 2019, 47, E12.

- Wheat, E.; Vlasea, M.; Hinebaugh, J.; Metcalfe, C. Sinter structure analysis of titanium structures fabricated via binder jetting additive manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2018, 156, 167–183.

- Tahayeri, A.; Morgan, M.; Fugolin, A.P.; Bompolaki, D.; Athirasala, A.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Ferracane, J.L.; Bertassoni, L.E. 3D printed versus conventionally cured provisional crown and bridge dental materials. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 192–200.

- Lowther, M.; Louth, S.; Davey, A.; Hussain, A.; Ginestra, P.; Carter, L.; Eisenstein, N.; Grover, L.; Cox, S. Clinical, industrial, and research perspectives on powder bed fusion additively manufactured metal implants. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 565–584.

- Akmal, J.S.; Salmi, M.; Hemming, B.; Linus, T.; Suomalainen, A.; Kortesniemi, M.; Partanen, J.; Lassila, A. Cumulative inaccuracies in implementation of additive manufacturing through medical imaging, 3D thresholding, and 3D modeling: A case study for an end-use implant. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2968.

- Tuomi, J.T.; Björkstrand, R.V.; Pernu, M.L.; Salmi, M.V.; Huotilainen, E.I.; Wolff, J.E.; Vallittu, P.K.; Mäkitie, A.A. In vitro cytotoxicity and surface topography evaluation of additive manufacturing titanium implant materials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2017, 28, 53.

- Balažic, M.; Recek, D.; Kramar, D.; Milfelner, M.; Kopač, J. Development process and manufactu-ring of modern medical implants with LENS technology. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2009, 32, 46–52.

- Honigmann, P.; Sharma, N.; Okolo, B.; Popp, U.; Msallem, B.; Thieringer, F.M. Patient-specific surgical implants made of 3D printed PEEK: Material, technology, and scope of surgical application. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4520636.

- Schwarzer, E.; Holtzhausen, S.; Scheithauer, U.; Ortmann, C.; Oberbach, T.; Moritz, T.; Michaelis, A. Process development for additive manufacturing of functionally graded alumina toughened zirconia components intended for medical implant application. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 522–530.

- Igawa, K.; Mochizuki, M.; Sugimori, O.; Shimizu, K.; Yamazawa, K.; Kawaguchi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Takato, T.; Nishimura, R.; Suzuki, S. Tailor-made tricalcium phosphate bone implant directly fabricated by a three-dimensional ink-jet printer. J. Artif. Organs 2006, 9, 234–240.

- Sharma, N.; Honigmann, P.; Cao, S.; Thieringer, F. Dimensional characteristics of FDM 3D printed PEEK implant for craniofacial reconstructions. Trans. Addit. Manuf. Meets Med. 2020, 2.

- Jardini, A.L.; Larosa, M.A.; Macedo, M.F.; Bernardes, L.F.; Lambert, C.S.; Zavaglia, C.; Maciel Filho, R.; Calderoni, D.R.; Ghizoni, E.; Kharmandayan, P. Improvement in cranioplasty: Advanced prosthesis biomanufacturing. Procedia Cirp 2016, 49, 203–208.

- Wilkes, J.; Hagedorn, Y.; Meiners, W.; Wissenbach, K. Additive manufacturing of ZrO2-Al2O3 ceramic components by selective laser melting. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2013, 19, 51–57.

- Culmone, C.; Smit, G.; Breedveld, P. Additive manufacturing of medical instruments: A state-of-the-art review. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 461–473.

- Kukko, K.; Akmal, J.S.; Kangas, A.; Salmi, M.; Björkstrand, R.; Viitanen, A.-K.; Partanen, J.; Joshua, M. Pearce Additively Manufactured Parametric Universal Clip-System: An Open Source Approach for Aiding Personal Exposure Measurement in the Breathing Zone. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6671.

- Salmi, M.; Tuomi, J.; Sirkkanen, R.; Ingman, T.; Makitie, A. Rapid tooling method for soft customized removable oral appliances. Open Dent. J. 2012, 6, 85–89.

- Salmi, M.; Akmal, J.S.; Pei, E.; Wolff, J.; Jaribion, A.; Khajavi, S.H. 3D Printing in COVID-19: Productivity Estimation of the Most Promising Open Source Solutions in Emergency Situations. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4004.

- Tiwary, V.K.; Arunkumar, P.; Deshpande, A.S.; Rangaswamy, N. Surface enhancement of FDM patterns to be used in rapid investment casting for making medical implants. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2019, 25, 904–914.

- Cloonan, A.J.; Shahmirzadi, D.; Li, R.X.; Doyle, B.J.; Konofagou, E.E.; McGloughlin, T.M. 3D-printed tissue-mimicking phantoms for medical imaging and computational validation applications. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1, 14–23.

- Sharma, N.; Cao, S.; Msallem, B.; Kunz, C.; Brantner, P.; Honigmann, P.; Thieringer, F.M. Effects of Steam Sterilization on 3D Printed Biocompatible Resin Materials for Surgical Guides—An Accuracy Assessment Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1506.

- Jahnke, P.; Schwarz, S.; Ziegert, M.; Schwarz, F.B.; Hamm, B.; Scheel, M. Paper-based 3D printing of anthropomorphic CT phantoms: Feasibility of two construction techniques. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 29, 1384–1390.

- Väyrynen, V.O.; Tanner, J.; Vallittu, P.K. The anisotropicity of the flexural properties of an occlusal device material processed by stereolithography. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 116, 811–817.

- Huotilainen, E.; Salmi, M.; Lindahl, J. Three-dimensional printed surgical templates for fresh cadaveric osteochondral allograft surgery with dimension verification by multivariate computed tomography analysis. Knee 2019, 26, 923–932.

- Cascón, W.P.; Revilla-León, M. Digital workflow for the design and additively manufacture of a splinted framework and custom tray for the impression of multiple implants: A dental technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 120, 805–811.

- Lathers, S.; La Belle, J. Advanced manufactured fused filament fabrication 3D printed osseointegrated prosthesis for a transhumeral amputation using Taulman 680 FDA. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 3, 166–174.

- Freeman, D.; Wontorcik, L. Stereolithography and prosthetic test socket manufacture: A cost/benefit analysis. JPO J. Prosthet. Orthot. 1998, 10, 17–20.

- Sengeh, D.M. Advanced Prototyping of Variable Impedance Prosthetic Sockets For Trans-Tibial Amputees: Polyjet Matrix 3D Printing of Comfortable Prosthetic Sockets Using Digital Anatomical Data. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012.

- Mohseni, M.; Bas, O.; Castro, N.J.; Schmutz, B.; Hutmacher, D.W. Additive biomanufacturing of scaffolds for breast reconstruction. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100845.

- Poh, P.S.; Chhaya, M.P.; Wunner, F.M.; De-Juan-Pardo, E.M.; Schilling, A.F.; Schantz, J.; van Griensven, M.; Hutmacher, D.W. Polylactides in additive biomanufacturing. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 228–246.

- Cao, S.; Han, J.; Sharma, N.; Msallem, B.; Jeong, W.; Son, J.; Kunz, C.; Kang, H.; Thieringer, F.M. In Vitro Mechanical and Biological Properties of 3D Printed Polymer Composite and β-Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffold on Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Materials 2020, 13, 3057.

- Inzana, J.A.; Olvera, D.; Fuller, S.M.; Kelly, J.P.; Graeve, O.A.; Schwarz, E.M.; Kates, S.L.; Awad, H.A. 3D printing of composite calcium phosphate and collagen scaffolds for bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4026–4034.

- Schult, M.; Buckow, E.; Seitz, H. Experimental studies on 3D printing of barium titanate ceramics for medical applications. Curr. Dir. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 2, 95–99.

- Sahu, K.K.; Modi, Y.K. Investigation on dimensional accuracy, compressive strength and measured porosity of additively manufactured calcium sulphate porous bone scaffolds. Mater. Technol. 2020, 1–12.

- Oh, W.J.; Lee, W.J.; Kim, M.S.; Jeon, J.B.; Shim, D.S. Repairing additive-manufactured 316L stainless steel using direct energy deposition. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 117, 6–17.

- Szymor, P.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Olszewski, R. Accuracy of open-source software segmentation and paper-based printed three-dimensional models. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 44, 202–209.

- Olszewski, R.; Tilleux, C.; Hastir, J.; Delvaux, L.; Danse, E. Holding Eternity in One’s Hand: First Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Printing of the Heart from 2700 Years-Old Egyptian Mummy. Anat. Rec. 2019, 302, 912–916.

- Ward, A.A.; Cordero, Z.C. Junction growth and interdiffusion during ultrasonic additive manufacturing of multi-material laminates. Scr. Mater. 2020, 177, 101–105.

- Feuerbach, T.; Kock, S.; Thommes, M. Characterisation of fused deposition modeling 3D printers for pharmaceutical and medical applications. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2018, 23, 1136–1145.

- Ait-Mansour, I.; Kretzschmar, N.; Chekurov, S.; Salmi, M.; Rech, J. Design-dependent shrinkage compensation modeling and mechanical property targeting of metal FFF. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 5, 51–57.

- Adumitroaie, A.; Antonov, F.; Khaziev, A.; Azarov, A.; Golubev, M.; Vasiliev, V.V. Novel Continuous Fiber Bi-Matrix Composite 3-D Printing Technology. Materials 2019, 12, 3011.

- Gibson, M.A.; Mykulowycz, N.M.; Shim, J.; Fontana, R.; Schmitt, P.; Roberts, A.; Ketkaew, J.; Shao, L.; Chen, W.; Bordeenithikasem, P. 3D printing metals like thermoplastics: Fused filament fabrication of metallic glasses. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 697–702.

- Wolff, M.; Mesterknecht, T.; Bals, A.; Ebel, T.; Willumeit-Römer, R. FFF of Mg-Alloys for Biomedical Application. In Magnesium Technology 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 43–49.

- Spencer, S.R.; Watts, L.K. Three-Dimensional Printing in Medical and Allied Health Practice: A Literature Review. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2020, 51, 489–500.

- Miyanaji, H.; Rahman, K.M.; Da, M.; Williams, C.B. Effect of fine powder particles on quality of binder jetting parts. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101587.

- Huang, S.; Ye, C.; Zhao, H.; Fan, Z. Parameters optimization of binder jetting process using modified silicate as a binder. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2020, 35, 214–220.

- Ziaee, M.; Crane, N.B. Binder jetting: A review of process, materials, and methods. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 781–801.

- Chhaya, M.P.; Poh, P.S.; Balmayor, E.R.; van Griensven, M.; Schantz, J.; Hutmacher, D.W. Additive manufacturing in biomedical sciences and the need for definitions and norms. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2015, 12, 537–543.