Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADASs) are used for increasing safety in the automotive domain, yet current ADASs notably operate without taking into account drivers’ states, e.g., whether she/he is emotionally apt to drive.

- Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems

1. Concept, History and Development

ADAS were first being used in the 1950s with the adoption of the anti-lock braking system.[4] Early ADAS include electronic stability control, anti-lock brakes, blind spot information systems, lane departure warning, adaptive cruise control, and traction control. These systems can be affected by mechanical alignment adjustments or damage from a collision. This has led many manufacturers to require automatic resets for these systems after a mechanical alignment is performed.

Technical concepts

The reliance on data that describes the outside environment of the vehicle, compared to internal data, differentiates ADAS from driver-assistance systems (DAS).[4] ADAS relies on inputs from multiple data sources, including automotive imaging, LiDAR, radar, image processing, computer vision, and in-car networking. Additional inputs are possible from other sources separate from the primary vehicle platform, including other vehicles (vehicle-to-vehicle or V2V communication) and infrastructure (vehicle-to-infrastructure or V2I communication).[5]

1. Introduction

In recent years, the automotive field has been pervaded by an increasing level of automation. This automation has introduced new possibilities with respect to manual driving. Among all the technologies for vehicle driving assistance, on-board Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADASs), employed in cars, trucks, etc.[1], bring about remarkable possibilities in improving the quality of driving, safety, and security for both drivers and passengers. Examples of ADAS technologies are Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC)[2], Anti-lock Braking System (ABS)[3], alcohol ignition interlock devices[4], automotive night vision[5], collision avoidance systems[6], driver drowsiness detection[7], Electronic Stability Control (ESC)[8], Forward Collision Warnings (FCW)[9], Lane Departure Warning System (LDWS)[10], and Traffic Sign Recognition (TSR)[11]. Most ADASs consist of electronic systems developed to adapt and enhance vehicle safety and driving quality. They are proven to reduce road fatalities by compensating for human errors. To this end, safety features provided by ADASs target accident and collision avoidance, usually realizing safeguards, alarms, notifications, and blinking lights and, if necessary, taking control of the vehicle itself.

ADASs rely on the following assumptions: (i) the driver is attentive and emotionally ready to perform the right operation at the right time, and (ii) the system is capable of building a proper model of the surrounding world and of making decisions or raising alerts accordingly. Unfortunately, even if modern vehicles are equipped with complex ADASs (such as the aforementioned ones), the number of crashes is only partially reduced by their presence. In fact, the human driver is still the most critical factor in about 94% of crashes[12].

However, most of the current ADASs implement only simple mechanisms to take into account drivers’ states or do not take them into account it at all. An ADAS informed about the driver’s state could take contextualized decisions compatible with his/her possible reactions. Knowing the driver’s state means to continuously recognize whether the driver is physically, emotionally, and physiologically apt to guide the vehicle as well as to effectively communicate these ADAS decisions to the driver. Such an in-vehicle system to monitor drivers’ alertness and performance is very challenging to obtain and, indeed, would come with many issues.

-

The incorrect estimation of a driver’s state as well as of the status of the ego-vehicle (also denoted as subject vehicle or Vehicle Under Test (VUT) and referring to the vehicle containing the sensors perceiving the environment around the vehicle itself)[13][14] and the external environment may cause the ADAS to incorrectly activate or to make wrong decisions. Besides immediate danger, wrong decisions reduce drivers’ confidence in the system.

-

Many sensors are needed to achieve such an ADAS. Sensors are prone to errors and require several processing layers to produce usable outputs, where each layer introduces delays and may hide/damage data.

-

Dependable systems that recognize emotions and humans’ states are still a research challenge. They are usually built around algorithms requiring heterogeneous data as input parameters as well as provided by different sensing technologies, which may introduce unexpected errors into the system.

-

An effective communication between the ADAS and the driver is hard to achieve. Indeed, human distraction plays a critical role in car accidents[15] [15] and can be caused by both external and internal causes.

In this paper, we first present a literature review on the application of human state recognition for ADAS, covering psychological models, the sensors employed for capturing physiological signals, algorithms used for human emotion classification, and algorithms for human–car interaction. In particular, some of the aspects that researchers are trying to address can be summarized as follows:

-

adoption of tactful monitoring of psychological and physiological parameters (e.g., eye closure) able to significantly improve the detection of dangerous situations (e.g., distraction and drowsiness)

-

improvement in detecting dangerous situations (e.g., drowsiness) with a reasonable accuracy and based on the use of driving performance measures (e.g., through monitoring of “drift-and-jerk” steering as well as detection of fluctuations of the vehicle in different directions)

-

introduction of “secondary” feedback mechanisms, subsidiary to those originally provided in the vehicle, able to further enhance detection accuracy—this could be the case of auditory recognition tasks returned to the vehicle’s driver through a predefined and prerecorded human voice, which is perceived by the human ear in a more acceptable way compared to a synthetic one.

Modern cars have ADAS integrated into their electronics; manufacturers can add these new features. ADAS are considered real-time systems since they react quickly to multiple inputs and prioritize the incoming information to prevent accidents.[6] The systems use preemptive priority scheduling to organize which task needs to be done first.[6] The incorrect assignment of these priorities is what can cause more harm than good.[6]

ADAS levels

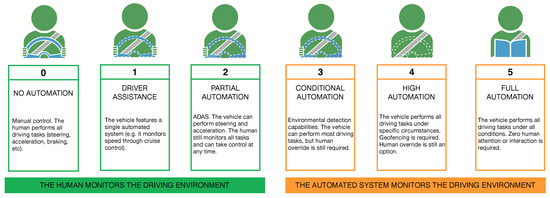

ADAS are categorized into different levels based on the amount of automation, and the scale provided by The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE).[4] ADAS can be divided into five levels. In level 0, ADAS cannot control the car and can only provide information for the driver to interpret on their own.[4] Some ADAS that are considered level 0 are: parking sensors, surround-view, traffic sign recognition, lane departure warning, night vision, blind spot information system, rear-cross traffic alert, and forward-collision warning.[4] Level 1 and 2 are very similar in that they both have the driver do most of the decision making. The difference is level 1 can take control over one functionality and level 2 can take control over multiple to aid the driver.[4] ADAS that are considered level 1 are: adaptive cruise control, emergency brake assist, automatic emergency brake assist, lane-keeping, and lane centering.[4] ADAS that are considered level 2 are: highway assist, autonomous obstacle avoidance, and autonomous parking.[4] From level 3 to 5, the amount of control the vehicle has increases; level 5 being where the vehicle is fully autonomous. Some of these systems have not yet been fully embedded in commercial vehicles. For instance, highway chauffeur is a Level 3 system, and automatic valet parking is a level 4 system, both of which are not in full commercial use yet.[4] The levels can be roughly understood as Level 0 - no automation; Level 1 - hands on/shared control; Level 2 - hands off; Level 3 - eyes off; Level 4 - mind off, and Level 5 - steering wheel optional. ADAS are among the fastest-growing segments in automotive electronics due to steadily increasing adoption of industry-wide quality and safety standards.[7][8]

2. Feature Examples

This list is not a comprehensive list of all of the ADAS. Instead, it provides information on critical examples of ADAS that have progressed and become more commonly available since 2015.[9][10]

- Adaptive cruise control (ACC) can maintain a chosen velocity and distance between a vehicle and the vehicle ahead. ACC can automatically brake or accelerate with concern to the distance between the vehicle and the vehicle ahead.[11] ACC systems with stop and go features can come to a complete stop and accelerate back to the specified speed.[12] This system still requires an alert driver to take in their surroundings, as it only controls speed and the distance between you and the car in front of you.[11]

- Alcohol ignition interlock devices do not allow drivers to start the car if the breath alcohol level is above a pre-described amount. The Automotive Coalition for Traffic Safety and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration have called for a Driver Alcohol Detection System for Safety (DADSS) program to put alcohol detection devices in all cars.[13]

- Anti-lock braking system (ABS) restore traction to a car’s tires by regulating the brake pressure when the vehicle begins to skid.[14] Alongside helping drivers in emergencies, such as when their car starts to skid on ice, ABS systems can also assist drivers who may lose control of their vehicle.[14] With the growing popularity in the 1990s, ABS systems have become standard in vehicles.[14]

- Automatic parking fully takes over control of parking functions, including steering, braking, and acceleration, to assist drivers in parking.[15] Depending on the relative cars and obstacles, the vehicle positions itself safely into the available parking spot.[15] Currently, the driver must still be aware of the vehicle’s surroundings and be willing to take control of it if necessary.

- Automotive head-up display (auto-HUD) safely displays essential system information to a driver at a vantage point that does not require the driver to look down or away from the road.[16] Currently, the majority of the auto-HUD systems on the market display system information on a windshield using LCDs.[16]

- Automotive navigation system use digital mapping tools, such as the global positioning system (GPS) and traffic message channel (TMC), to provide drivers with up to date traffic and navigation information.[17] Through an embedded receiver, an automotive navigation system can send and receive data signals transmitted from satellites regarding the current position of the vehicle in relation to its surroundings.[17]

- Automotive night vision systems enable the vehicle to detect obstacles, including pedestrians, in a nighttime setting or heavy weather situation when the driver has low visibility. These systems can various technologies, including infrared sensors, GPS, Lidar, and Radar, to detect pedestrians and non-human obstacles.[17]

- Backup camera provides real-time video information regarding the location of your vehicle and its surroundings.[18] This camera offers driver’s aid when backing up by providing a viewpoint that is typically a blind spot in traditional cars.[19] When the driver puts the car in reverse, the camera automatically turns on.[19]

- Blind spot monitor involves cameras that monitor the driver's blind spots and notify the driver if any obstacles come close to the vehicle.[19] Blind spots are defined as the areas behind or at the side of the vehicle that the driver cannot see from the driver’s seat.[19] Blind-spot monitoring systems typically work in conjunction with emergency braking systems to act accordingly if any obstacles come into the vehicle’s path. A rear cross traffic alert (RCTA) typically works in conjunction with the blind spot monitoring system, warning the driver of approaching cross-traffic when reversing out of a parking spot.[20]

- Collision avoidance system (pre-crash system) uses small radar detectors, typically placed near the front of the car, to determine the car’s vicinity to nearby obstacles and notify the driver of potential car crash situations.[21] These systems can account for any sudden changes to the car’s environment that may cause a collision.[21] Systems can respond to a possible collision situation with multiple actions, such as sounding an alarm, tensing up passengers’ seat belts, closing a sunroof, and raising reclined seats.[21]

- Crosswind stabilization helps prevent a vehicle from overturning when strong winds hit its side by analyzing the vehicle’s yaw rate, steering angle, lateral acceleration, and velocity sensors.[22] This system distributes the wheel load in relation to the velocity and direction of the crosswind.[22]

- Cruise control can maintain a specific speed pre-determined by the driver.[23] The car will maintain the speed the driver sets until the driver hits the brake pedal, clutch pedal, or disengages the system.[23] Specific cruise control systems can accelerate or decelerate, but require the driver to click a button and notify the car of the goal speed.[23]

- Driver drowsiness detection aims to prevent collisions due to driver fatigue.[24] The vehicle obtains information, such as facial patterns, steering movement, driving habits, turn signal use, and driving velocity, to determine if the driver’s activities correspond with drowsy driving.[25] If drowsy driving is suspected, the vehicle will typically sound off a loud alert and may vibrate the driver's seat.[25]

- Driver monitoring system is designed to monitor the alertness of the driver.[26] These systems use biological and performance measures to assess the driver’s alertness and ability to conduct safe driving practices.[26] Currently, these systems use infrared sensors and cameras to monitor the driver’s attentiveness through eye-tracking.[26] If the vehicle detects a possible obstacle, it will notify the driver and if no action is taken, the vehicle may react to the obstacle.

- Electric vehicle warning sounds notify pedestrians and cyclists that a hybrid or plug-in electric vehicle is nearby, typically delivered through a noise, such as a beep or horn.[27] This technology was developed in response to the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration ruling that issued 50 percent of quiet vehicles must have a device implemented into their systems that sound off when the vehicle travels at speeds less than 30km/h (18.6 mph) by September 2019.[28]

- Electronic stability control (ESC) can lessen the speed of the car and activate individual brakes to prevent understeer and oversteer.[29] Understeer occurs when the car’s front wheels don’t have enough traction to make the car turn and oversteer occurs when the car turns more than intended, causing the car to spin out.[29] In conjunction with other car safety technologies, such as anti-lock braking and traction control, the ESC can safely help drivers maintain control of the car in unforeseen situations.[29]

- Emergency driver assistant facilitates emergency counteract measures if the driver falls asleep or does not perform any driving action after a defined length of time.[30] After a specified period of time, if the driver has not interacted with the accelerator, brake, or steering wheel, the car will send audio, visual, and physical signals to the driver.[30] If the driver does not wake up after these signals, the system will stop, safely position the vehicle away from oncoming traffic, and turn on the hazard warning lights.[30]

- Forward collision warning (FCW) monitor the speed of the vehicle and the vehicle in front of it, and the open distance around the vehicle.[31] FCW systems will send an alert to the driver of a possible impending collision if gets too close to the vehicle in front of it.[31] These systems do not take control of the vehicle, as currently, FCW systems only send an alert signal to the driver in the form of an audio alert, visual pop-up display, or other warning alert.[31]

- Intersection assistants use two radar sensors in the front bumper and sides of the car to monitor if there are any oncoming cars at intersections, highway exits, or car parks.[32] This system alerts the driver of any upcoming traffic from the vehicle’s sides and can enact the vehicle’s emergency braking system to prevent the collision.[32]

- Glare-free high beam use Light Emitting Diodes, more commonly known as LEDs, to cut two or more cars from the light distribution.[33] This allows oncoming vehicles coming in the opposite direction not to be affected by the light of the high-beams. In 2010, the VW Touareg introduced the first glare-free high beam headlamp system, which used a mechanical shutter to cut light from hitting specific traffic participants.[33]

- Hill descent control helps drivers maintain a safe speed when driving down a hill or other decline.[34] These systems are typically enacted if the vehicle moves faster than 15 to 20 mph when driving down. When a change in grade is sensed, hill descent control automates the driver’s speed to descend down the steep grade safely.[34] This system works by pulsing the braking system and controlling each wheel independently to maintain traction down the descent.[34]

- Hill-start assist also known as hill-start control or hill holder, helps prevent a vehicle from rolling backward down a hill when starting again from a stopped position.[35] This feature holds the brake for you while you transition between the brake pedal and the gas pedal.[35] For manual cars, this feature holds the brake for you while you transition between the brake pedal, the clutch, and the gas pedal.[35]

- Intelligent speed adaptation or intelligent speed advice (ISA) assists drivers with compliance to the speed limit. They take in information of the vehicle’s position and notify the driver when he/she is not enforcing the speed limit.[36] Some ISA systems allow the vehicle to adjust its speed to adhere to the relative speed limit.[36] Other ISA systems only warn the driver when he/she is going over the speed limit and leave it up to the driver to enforce the speed limit or not.[36]

- Lane centering assists the driver in keeping the vehicle centered in a lane.[37] A lane-centering system may autonomously take over the steering when it determines the driver is at risk of deterring from the lane.[37] This system uses cameras to monitor lane markings to stay within a safe distance between both sides of the lane.[38]

- Lane departure warning system (LDW) alerts the driver when they partially merge into a lane without using their turn signals.[39] An LDW system uses cameras to monitor lane markings to determine if the driver unintentionally begins to drift.[39] This system does not take control of the vehicle to help sway the car back into the safety zone but instead sends an audio or visual alert to the driver.[39]

- Lane change assistance helps the driver through a safe completion of a lane change by using sensors to scan the vehicle’s surroundings and monitor the driver’s blind spots.[40] When a driver intends to make a lane change, the vehicle will notify the driver through an audio or visual alert when a vehicle is approaching from behind or is in the vehicle’s blind spot.[40] The visual alert may appear in the dashboard, heads-up-display, or the exterior rear-view mirrors.[41] Several kind of lane change assistance might exist, for instance UNECE regulation 79 considers:

- "ACSF (Automatically commanded steering function) of Category C" (...) a function which is initiated/activated by the driver and which can perform a single lateral manoeuvre (e.g. lane change) when commanded by the driver.

- "ACSF of Category D" (...) a function which is initiated/activated by the driver and which can indicate the possibility of a single lateral manoeuvre (e.g. lane change) but performs that function only following a confirmation by the driver.

- "ACSF of Category E" (...) a function which is initiated/activated by the driver and which can continuously determine the possibility of a manoeuvre (e.g. lane change) and complete these manoeuvres for extended periods without further driver command/confirmation.

—UNECE regulation 79[42]

- Parking sensors can scan the vehicle’s surroundings for objects when the driver initiates parking.[43] Audio warnings can notify the driver of the distance between the vehicle and its surrounding objects.[43] Typically, the faster the audio warnings are issued, the closer the vehicle is getting to the object.[43] These sensors may not detect objects closer to the ground, such as parking stops, which is why parking sensors typically work alongside backup cameras to assist the driver when reversing into a parking spot.[43]

- Pedestrian protection systems are designed to minimize the number of accidents or injuries that occur between a vehicle and a pedestrian.[44] This system uses cameras and sensors to determine when the front of a vehicle strikes a pedestrian.[44] When the collision occurs, the vehicle’s bonnet lifts to provide a cushion between the vehicle’s hard engine components and the pedestrian.[44] This helps minimize the possibility of a severe head injury when the pedestrian’s head comes into contact with the vehicle.[44]

- Rain sensors detect water and automatically trigger electrical actions, such as the raising of open windows and the closing of open convertible tops.[45] A rain sensor can also take in the frequency of rain droplets to automatically trigger windshield wipers with an accurate speed for the corresponding rainfall.[45]

- Omniview technology improves a driver’s visibility by offering a 360-degree viewing system.[46] This system can accurately provide 3D peripheral images of the car’s surroundings through video display outputted to the driver.[46] Currently, commercial systems can only provide 2D images of the driver’s surroundings. Omniview technology uses the input of four cameras and a bird’s eye technology to provide a composite 3D model of the surroundings.[46]

- Tire pressure monitoring determine when the tire pressure is outside the normal inflation pressure range.[47] The driver can monitor the tire pressure and is notified when there is a sudden drop through a pictogram display, gauge, or low-pressure warning signal.[47]

- Traction control system (TCS) helps prevent traction loss in vehicles and prevent vehicle turnover on sharp curves and turns.[48] By limiting tire slip, or when the force on a tire exceeds the tire’s traction, this limits power delivery and helps the driver accelerate the car without losing control.[48] These systems use the same wheel-speed sensors as the antilock braking systems.[48] Individual wheel braking systems are deployed through TCS to control when one tire spins faster than the others.[48]

- Traffic sign recognition (TSR) systems can recognize common traffic signs, such as a “stop” sign or a “turn ahead” sign, through image processing techniques.[49] This system takes into account the sign’s shape, such as hexagons and rectangles, and the color to classify what the sign is communicating to the driver.[49] Since most systems currently use camera-based technology, a wide variety of factors can make the system less accurate. These include poor lighting conditions, extreme weather conditions, and partial obstruction of the sign.[49]

- Vehicular communication systems come in three forms: vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), and vehicle-to-everything (V2X). V2V systems allow vehicles to exchange information with each other about their current position and upcoming hazards.[50] V2I systems occur when the vehicle exchanges information with nearby infrastructure elements, such as street signs.[50] V2X systems occur when the vehicle monitors its environment and takes in information about possible obstacles or pedestrians in its path.[50]

- Vibrating seat warnings alert the driver of danger. GM’s Cadillacs have offered vibrating seat warnings since the 2013 Cadillac ATS. If the driver begins drifting out of the traveling lane of a highway, the seat vibrates in the direction of the drift, warning the driver of danger. The safety alert seat also provides a vibrating pulse on both sides of the seat when a frontal threat is detected.[51]

- Wrong-way driving warning issue alerts to drivers when it is detected that they are on the wrong side of the road.[52] Vehicles with this system enacted can use sensors and cameras to identify the direction of oncoming traffic flow.[52] In conjunction with lane detection services, this system can also notify drivers when they partially merge into the wrong side of the road [52]

3. Need for Standardization

According to PACTS, lack of full standardization might make the system have difficultly being understandable by the driver who might believe that the car behave like another car while it does not.[53]

we can’t help feeling that this lack of standardisation is one of the more problematic aspects of driver-assistance systems; and it’s one that is likely to be felt more keenly as systems become increasingly commonplace in years to come, particularly if traffic laws change to allow ‘hands-off’ driving in the future.—EuroNCAP[54]

ADAS might have many limitations, for instance a pre-collision system might have 12 pages to explain 23 exceptions where ADAS may operate when not needed and 30 exceptions where ADAS may not operate when a collision is likely.[53] Names for ADAS features are not standardized. For instance, adaptive cruise control is called Adaptive Cruise Control by Fiat, Ford, GM, VW, Volvo and Peugeot, but Intelligent Cruise Control by Nissan, Active Cruise Control by Citroen and BMW, and DISTRONIC by Mercedes.[53] To help with standardization, SAE International has endorsed a series of recommendations for generic ADAS terminology for car manufacturers, that it created with Consumer Reports, the American Automobile Association, J.D. Power, and the National Safety Council.[55][56] Buttons and dashboard symbols change from car to car due to lack of standardization.[53][57] ADAS behavior might change from car to car, for instance ACC speed might be temporarily overridden in most cars, while some switch to standby after one minute.[53]

4. Europe

In Europe, in Q2 2018, 3% of sold passenger cars had level 2 autonomy driving features. In Europe, in Q2 2019, 325,000 passenger cars are sold with level 2 autonomy driving features, that is 8% of all new cars sold.[58] <graph>{"legends":[{"properties":{"legend":{"y":{"value":-90}},"title":{"fill":{"value":"#54595d"}},"labels":{"fill":{"value":"#54595d"}}},"stroke":"color","title":"Level 2 features in car sold during Q2 2019","fill":"color"}],"scales":[{"domain":{"data":"chart","field":"x"},"type":"ordinal","name":"color","range":"category10"}],"version":2,"marks":[{"type":"arc","properties":{"hover":{"fill":{"value":"red"}},"update":{"fill":{"scale":"color","field":"x"}},"enter":{"endAngle":{"field":"layout_end"},"innerRadius":{"value":0},"outerRadius":{"value":90},"startAngle":{"field":"layout_start"},"stroke":{"value":"white"},"fill":{"scale":"color","field":"x"},"strokeWidth":{"value":1}}},"from":{"data":"chart","transform":[{"type":"pie","field":"y"}]}},{"type":"text","properties":{"enter":{"theta":{"field":"layout_mid"},"baseline":{"value":"top"},"align":{"value":"center"},"text":{"template":"{{datum.y|number:'.0p'}}"},"y":{"group":"height","mult":0.5},"x":{"group":"width","mult":0.5},"fontSize":{"value":9},"angle":{"mult":57.29577951308232,"field":"layout_mid"},"radius":{"offset":-4,"value":90},"fill":{"value":"white"}}},"from":{"data":"chart","transform":[{"field":"y","type":"pie"}]}}],"height":200,"axes":[],"data":[{"format":{"parse":{"y":"number","x":"string"},"type":"json"},"name":"chart","values":[{"y":0.2,"x":"Toyota"},{"y":0.15,"x":"BMW"},{"y":0.14,"x":"Mercedes-Benz"},{"y":0.12,"x":"Volvo"},{"y":0.11,"x":"Audi"},{"y":0.28,"x":"Others"}]}],"width":90}</graph> Major car brands with Level 2 features include Audi, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Tesla, Volvo, Citroën, Ford, Hyundai, Kia, Mazda, Nissan and Peugeot.[58] Full Level 2 features are included with Full Self-Driving from Tesla, Pilot Assist from Volvo and ProPILOT Assist from Nissan.[58]

5. Insurance and Economic Impact

The AV industry is growing exponentially, and according to a report by Market Research Future, the market is expected to hit over $65 billion by 2027. AV insurance and rising competition are expected to fuel that growth.[59] Auto insurance for ADAS has directly affected the global economy, and many questions have arisen within the general public. ADAS allows autonomous vehicles to enable self-driving features, but there are associated risks with ADAS. AV companies and manufacturers are recommended to have insurance in the following areas in order to avoid any serious litigations. Depending on the level, ranging from 0 to 5, each car manufacturer would find it in its best interest to find the right combination of different insurances to best match their products. Note that this list is not exhaustive and may be constantly updated with more types of insurances and risks in the years to come.

- Technology errors and omissions – This insurance will cover any physical risk if the technology itself has failed. These usually include all of the associated expenses of a car accident.[60]

- Auto liability and physical damage – This insurance covers third-party injuries and technology damage.[60]

- Cyber liability – This insurance will protect companies from any lawsuits from third parties and penalties from regulators regarding cybersecurity.[61]

- Directors and officers – This insurance protects a company’s balance sheet and assets by protecting the company from bad management or misappropriation of assets.[61]

With the technology embedded in autonomous vehicles, these self-driving cars are able to distribute data if a car accident occurs. This, in turn, will invigorate the claims administration and their operations. Fraud reduction will also disable any fraudulent staging of car accidents by recording the car’s monitoring of every minute on the road.[62] ADAS is expected to streamline the insurance industry and its economic efficiency with capable technology to fight off fraudulent human behavior. In September 2016, the NHTSA published the Federal Automated Vehicles Policy, which describes the U.S. Department of Transportation's policies related to highly automated vehicles (HAV) which range from vehicles with ADAS features to autonomous vehicles.

6. Ethical Issues and Current Solutions

- In March 2014, the US Department of Transportation's National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) announced that it will require all new vehicles under 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) to have rear view cameras by May 2018. The rule was required by Congress as part of the Cameron Gulbransen Kids Transportation Safety Act of 2007. The Act is named after two-year-old Cameron Gulbransen. Cameron’s father backed up his SUV over him, when he did not see the toddler in the family’s driveway [63]

The advancement of autonomous driving is accompanied by ethical concerns. The earliest moral issue associated with autonomous driving can be dated back to as early as the age of the trolleys. The trolley problem is one of the most well-known ethical issues. Introduced by English philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967, the trolley problem asks that under a situation which the trolley’s brake does not work, and there are five people ahead of the trolley, the driver may go straight, killing the five persons ahead, or turn to the side track killing the one pedestrian, what should the driver do?[64] Before the development of autonomous vehicles, the trolley problem remains an ethical dilemma between utilitarianism and deontological ethics. However, as the advancement in ADAS proceeds, the trolley problem becomes an issue that needs to be addressed by the programming of self-driving cars. The accidents that autonomous vehicles might face could be very similar to those depicted in the trolley problem.[65] Although ADAS systems make vehicles generally safer than only human-driven cars, accidents are unavoidable.[65] This raises questions such as “whose lives should be prioritized in the event of an inevitable accident?” Or “What should be the universal principle for these ‘accident-algorithms’?” Many researchers have been working on ways to address the ethical concerns associated with ADAS systems. For instance, the artificial intelligence approach allows computers to learn human ethics by feeding them data regarding human actions.[66] Such a method is useful when the rules cannot be articulated because the computer can learn and identify the ethical elements on its own without precisely programming whether an action is ethical.[67] However, there are limitations to this approach. For example, many human actions are done out of self-preservation instincts, which is realistic but not ethical; feeding such data to the computer cannot guarantee that the computer captures the ideal behavior.[68] Furthermore, the data fed to an artificial intelligence must be carefully selected to avoid producing undesired outcomes.[68] Another notable method is a three-phase approach proposed by Noah J. Goodall. This approach first necessitates a system established with the agreement of car manufacturers, transportation engineers, lawyers, and ethicists, and should be set transparently.[68] The second phase is letting artificial intelligence learn human ethics while being bound by the system established in phase one.[68] Lastly, the system should provide constant feedback that is understandable by humans.[68]

7. Future

Intelligent transport systems (ITS) highly resemble ADAS, but experts believe that ITS goes beyond automatic traffic to include any enterprise that safely transports humans.[68] ITS is where the transportation technology is integrated with a city’s infrastructure.[69] This would then lead to a “smart city”.[69] These systems promote active safety by increasing the efficiency of roads, possibly by adding 22.5% capacity on average, not the actual count.[69] ADAS have aided in this increase in active safety, according to a study in 2008. ITS systems use a wide system of communication technology, including wireless technology and traditional technology, to enhance productivity.[68]

Moreover, the complex processing tasks of modern ADASs are increasingly tackled by AI-oriented techniques. AIs can solve complex classification tasks that were previously thought to be very hard (or even impossible). Human state estimation is a typical task that can be approached by AI classifiers. At the same time, the use of AI classifiers brings about new challenges. As an example, ADAS can potentially be improved by having a reliable human emotional state identified by the driver, e.g., in order to activate haptic alarms in case of imminent forward collisions. Even if such an ADAS could tolerate a few misclassifications, the AI component for human state classification needs to have a very high accuracy to reach an automotive-grade reliability. Hence, it should be possible to prove that a classifier is sufficiently robust against unexpected data [16].

We then introduce a novel perception architecture for ADAS based on the idea of Driver Complex State (DCS). The DCS of the vehicle’s driver monitors his/her behavior via multiple non-obtrusive sensors and AI algorithms, providing emotion cognitive classifiers and emotion state classifiers to the ADAS. We argue that this approach is a smart way to improve safety for all occupants of a vehicle. We believe that, to be successful, the system must adopt unobtrusive sensing technologies for human parameters detection, safe and transparent AI algorithms that satisfy stringent automotive requirements, as well as innovative Human–Machine Interface (HMI) functionalities. Our ultimate goal is to provide solutions that improve in-vehicle ADAS, increasing safety, comfort, and performance in driving. The concept will be implemented and validated in the recently EU-funded NextPerception project[17], which will be briefly introduced.

2. ADAS Using Driver Emotion Recognition

In the automotive sector, the ADAS industry is a growing segment aiming at increasing the adoption of industry-wide functional safety in accordance with several quality standards, e.g., the automotive-oriented ISO 26262 standard[21]. ADAS increasingly relies on standardized computer systems, such as the Vehicle Information Access API[22], Volkswagen Infotainment Web Interface (VIWI) protocol[23], and On-Board Diagnostics (OBD) codes [24], to name a few.

In order to achieve advanced ADAS beyond semiautonomous driving, there is a clear need for appropriate knowledge of the driver’s status. These cooperative systems are captured in the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) level hierarchy of driving automation, summarized in Figure 1. These levels range from level 0 (manual driving) to level 5 (fully autonomous vehicle), with intermediate levels representing semiautonomous driving situations, with a mixed driver–vehicle degree of cooperation.

According to SAE levels, in these mixed systems, automation is partial and does not cover every possible anomalous condition that can happen during driving. Therefore, the driver’s active presence and his/her reaction capability remain critical. In addition, the complex data processing needed for higher automation levels will almost inevitably require various forms of AI (e.g., Machine Learning (ML) components), in turn bringing security and reliability issues.

Driver Monitoring Systems (DMSs) are a novel type of ADAS that has emerged to help predict driving maneuvers, driver intent, and vehicle and driver states, with the aim of improving transportation safety and driving experience as a whole[25]. For instance, by coupling sensing information with accurate lane changing prediction models, a DMS can prevent accidents by warning the driver ahead of time of potential danger[26]. As a measure of the effectiveness of this approach, progressive advancements of DMSs can be found in a number of review papers. Lane changing models have been reviewed in[27], while in [28][29], developments in driver’s intent prediction with emphasis on real-time vehicle trajectory forecasting are surveyed. The work in[30] reviews driver skills and driving behavior recognition models. A review of the cognitive components of driver behavior can also be found in[7], where situational factors that influence driving are addressed. Finally, a recent survey on human behavior prediction can be found in[31].

References

- Ziebinski, A.; Cupek, R.; Grzechca, D.; Chruszczyk, L. Review of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS). AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1906, 120002.

- • Vollrath, M.; Schleicher, S.; Gelau, C. The Influence of Cruise Control and Adaptive Cruise Control on Driving Behaviour—A driving simulator study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1134–1139.

- • Satoh, M.; Shiraishi, S. Performance of Antilock Brakes with Simplified Control Technique. In SAE International Congress and Exposition; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1983.

- • Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Increasing Alcohol Ignition Interlock Use. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/impaired_driving/ignition_interlock_states.html (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- • Martinelli, N.S.; Seoane, R. Automotive Night Vision System. In Thermosense XXI. International Society for Optics and Photonics; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1999; Volume 3700, pp. 343–346.

- • How Pre-Collision Systems Work. Available online: https://auto.howstuffworks.com/car-driving-safety/safety-regulatory-devices/pre-collision-systems.htm (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- • Jacobé de Naurois, C.; Bourdin, C.; Stratulat, A.; Diaz, E.; Vercher, J.L. Detection and Prediction of Driver Drowsiness using Artificial Neural Network Models. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 126, 95–104.PubMed

- • How Electronic Stability Control Works. Available online: https://auto.howstuffworks.com/car-driving-safety/safety-regulatory-devices/electronic-stability-control.htm (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- • Wang, C.; Sun, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Fu, R. A Forward Collision Warning System based on Self-Learning Algorithm of Driver Characteristics. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 38, 1519–1530.

- • Kortli, Y.; Marzougui, M.; Atri, M. Efficient Implementation of a Real-Time Lane Departure Warning System. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Image Processing, Applications and Systems (IPAS), Hammamet, Tunisia, 5–7 November 2016; pp. 1–6.

- • Luo, H.; Yang, Y.; Tong, B.; Wu, F.; Fan, B. Traffic Sign Recognition Using a Multi-Task Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 1100–1111.

- • Singh, S. Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey. Technical Report. (US Department of Transportation—National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). Report No. DOT HS 812 115. 2015. Available online: https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812506 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Ego Vehicle—Coordinate Systems in Automated Driving Toolbox. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/driving/ug/coordinate-systems.html (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- • Ego Vehicle—The British Standards Institution (BSI). Available online: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/CAV/cav-vocabulary/ego-vehicle/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- • Regan, M.A.; Lee, J.D.; Young, K. Driver Distraction: Theory, Effects, and Mitigation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008.

- • Tomkins, S. Affect Imagery Consciousness: The Complete Edition: Two Volumes; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008.

- • Russell, J.A. A Circumplex Model of Affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39.

- • Ekman, P. Basic Emotions. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Chapter 3; pp. 45–60.

- • International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 26262-1:2018—Road Vehicles—Functional Safety. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/68383.html (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- • Salman, H.; Li, J.; Razenshteyn, I.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Bubeck, S.; Yang, G. Provably Robust Deep Learning via Adversarially Trained Smoothed Classifiers. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 11292–11303. Available online: http://papers.nips.cc/paper/9307-provably-robust-deep-learning-via-adversarially-trained-smoothed-classifiers.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- • NextPerception—Next Generation Smart Perception Sensors and Distributed Intelligence for Proactive Human Monitoring in Health, Wellbeing, and Automotive Systems—Grant Agreement 876487. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/876487 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Vehicle Information Access API. Available online: https://www.w3.org/2014/automotive/vehicle_spec.html (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- • World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Volkswagen Infotainment Web Interface (VIWI) Protocol. Available online: https://www.w3.org/Submission/2016/SUBM-viwi-protocol-20161213/ (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- • Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE). SAE E/E Diagnostic Test Modes J1979_201702. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j1979_201702/ (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- • AbuAli, N.; Abou-zeid, H. Driver Behavior Modeling: Developments and Future Directions. Int. J. Veh. Technol. 2016, 2016.

- • Amparore, E.; Beccuti, M.; Botta, M.; Donatelli, S.; Tango, F. Adaptive Artificial Co-pilot as Enabler for Autonomous Vehicles and Intelligent Transportation Systems. In Proceedings of the 10th International Workshop on Agents in Traffic and Transportation (ATT 2018), Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018.

- • Rahman, M.; Chowdhury, M.; Xie, Y.; He, Y. Review of Microscopic Lane-Changing Models and Future Research Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2013, 14, 1942–1956.

- • Doshi, A.; Trivedi, M.M. Tactical Driver Behavior Prediction and Intent Inference: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 October 2011; pp. 1892–1897.

- • Moridpour, S.; Sarvi, M.; Rose, G. Lane Changing Models: A Critical Review. Transp. Lett. 2010, 2, 157–173.

- • Wang, W.; Xi, J.; Chen, H. Modeling and Recognizing Driver Behavior Based on Driving Data: A Survey. Math. Probl. Eng. 2014, 2014.

- • Brown, K.; Driggs-Campbell, K.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Modeling and Prediction of Human Driver Behavior: A Survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.08832.