Chronic nightmares are very common in psychiatric disorders, affecting up to 70% of patients with personality or post-traumatic stress disorders. In other psychiatric disorders, the relationships with nightmares are poorly known. This review aimed to clarify the relationship between nightmares and both mood and psychotic disorders.

- Chronic Nightmare in Psychiatric Disorders

1. Introduction

Sleep disorders are often implicated in the clinical course of psychiatric disorders. Among these sleep disorders, insomnia and nightmares are very common in clinical practice associated with psychiatric disorders [1]. Nightmares are associated with increased psychological distress [1], worse physical health outcomes [2], and increased risk of self-harm and suicide [3][4]. Whereas episodic nightmares are very common with a prevalence of about 35–45% (one nightmare per month) [5][6][7], the prevalence of chronic nightmares is relatively low in the general population, ranging from 2–8% [5][6][7][8][9][10]. Nevertheless, the prevalence of these chronic nightmares seems significantly more frequent in individuals with psychiatric disorders [11]. Indeed, chronic nightmares are very common in psychiatric disorders, affecting up to 70% of patients with personality or post-traumatic stress disorders [2][12][13]. In other psychiatric disorders such as psychotic and mood disorders, which are very frequent, the relationships between nightmares and these disorders is poorly known. The prevalence of nightmares is consistent across several countries and cultures, including the United States, Canada, Europe, Japan, and Middle East [14]. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition (ICSD-3) defines nightmares as “coherent dream sequences that seem real and become increasingly more disturbing as they unfold. Emotions usually involve anxiety, fear or terror. The dream content most often focuses on imminent physical danger to the individual, but may also involve other distressing themes” [15][16]. Nightmares occur frequently in the context of REM sleep, and would usually awaken the sleeper, with a recollection of disturbing mental activity [10].Episodic nightmares should be distinguished from a nightmare disorder. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [17] defines nightmare disorder according to five diagnostic criteria: (A) repeated occurrences of extended, extremely dysphoric and well-remembered dreams that generally occur during the second half of the major sleep episode; (B) the individual rapidly becomes oriented and alert on awakening from the dysphoric dreams; (C) the sleep disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning; (D) the nightmare symptoms are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance; (E) coexisting mental and medical disorders do not explain the predominant complaint of dysphoric dreams. The DSM-5 specifies the nightmare disorder’s duration: acute (<1 month), sub-acute (more than 1 month but less than 6 months) or persistent (>6 months). The DSM-5 also specifies the severity of the disorder: severe (one episode per night) and moderate disorder (one or more episode per week).Sleep complaints directly impact mental health and predict suicide attempts independently of all psychopathologies and sociodemographic characteristics [18]. More specifically, nightmares are overrepresented in almost all psychiatric disorders and are also associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors, as well as suicide, independently of psychiatric disorders and symptoms [19][20][21]. Moreover, nightmares are also associated with other suicide risk factors, including hopelessness and depression [22][23] which predict suicidal ideation and behavior [24][25]. Nightmares seem to be more frequent in patients with major depressive disorders (MDD), bipolar disorders (BD), and schizophrenia than in the general population [26]. It has also been proposed that nightmares and psychotic symptoms represent a common domain with shared pathophysiology [27]. Nevertheless, some findings are controversial, including whether these associations correlate or not with the intensity of psychiatric symptoms, or if the frequency and/or the intensity of nightmares are associated with psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviors. In addition, the question of whether nightmares are a specific or unspecific symptom shared by all or some psychiatric disorders still needs to be unraveled. Finally, although nightmares were associated with an increased risk of suicide in the general population, we wanted to clarify whether this association also exist in individuals with psychiatric disorders.

2. Related Studies

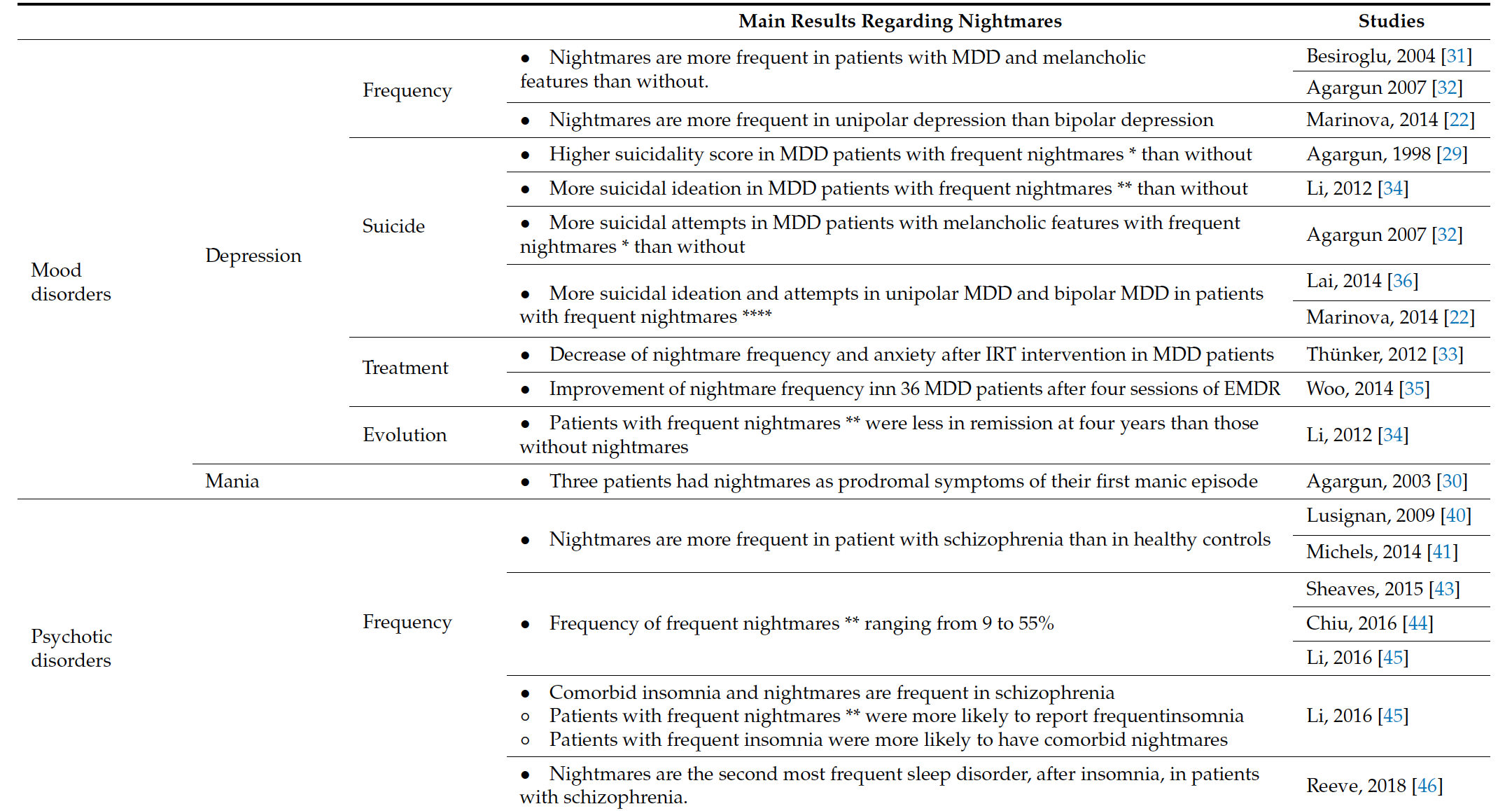

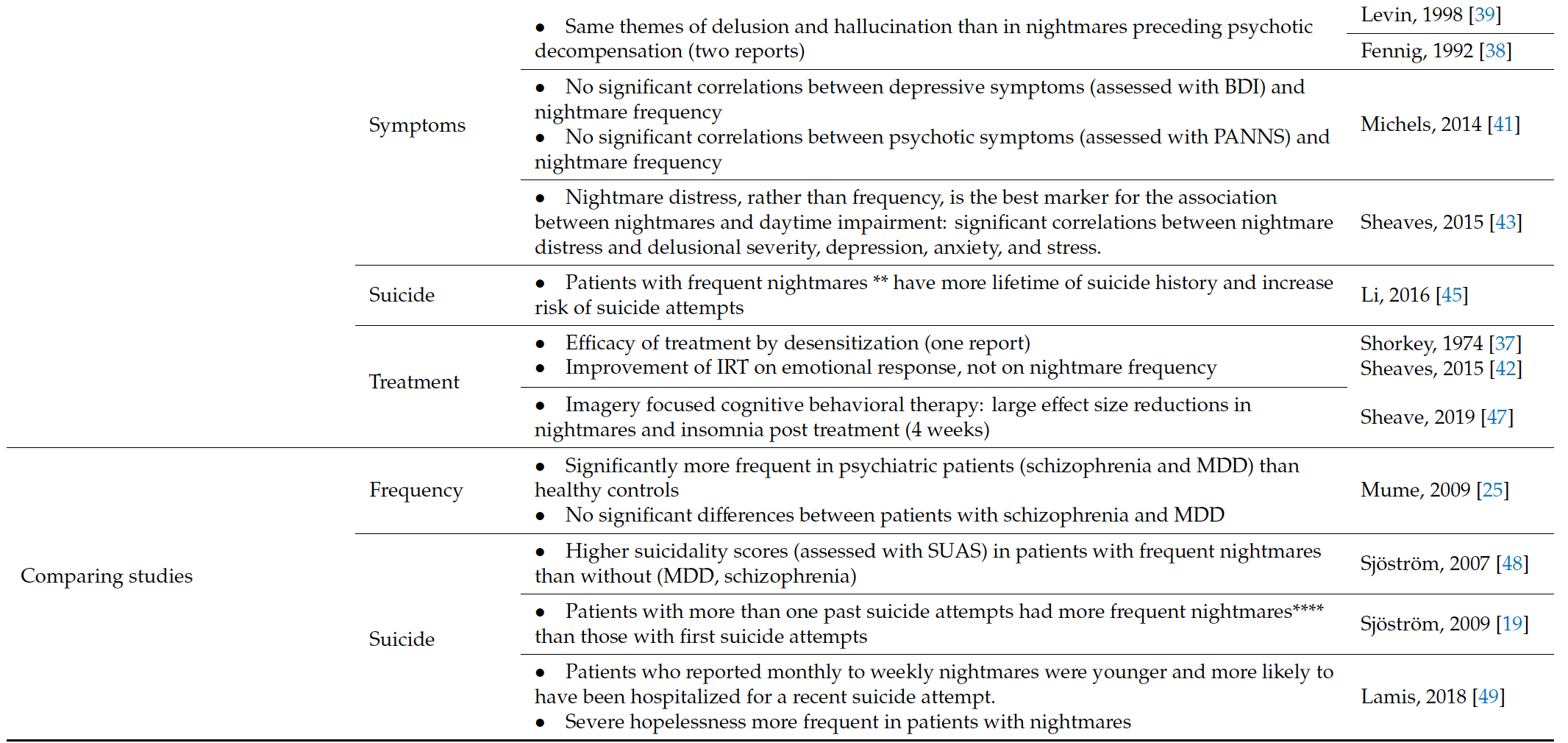

Nightmares were more frequent in individuals with mood disorders and psychotic disorders [26][28] than in individuals without psychiatric disorders. This is concordant with the observed higher prevalence of sleep complaints in psychiatric patients than in the general population [29]. Table 4 summarizes key findings from this systematic review of nightmares in mood and psychotic disorders (Table 4).Table 1. Synthesis of the findings from the literature.

| Main Results Regarding Nightmares | Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood disorders | Depression | Frequency | • Nightmares are more frequent in patients with MDD and melancholic features than without. | Besiroglu, 2004 [30] |

| Agargun 2007 [31] | ||||

| • Nightmares are more frequent in unipolar depression than bipolar depression | Marinova, 2014 [22] | |||

| Suicide | • Higher suicidality score in MDD patients with frequent nightmares * than without | Agargun, 1998 [29] | ||

| • More suicidal ideation in MDD patients with frequent nightmares ** than without | Li, 2012 [32] | |||

| • More suicidal attempts in MDD patients with melancholic features with frequent nightmares * than without | Agargun 2007 [31] | |||

| • More suicidal ideation and attempts in unipolar MDD and bipolar MDD in patients with frequent nightmares **** | Lai, 2014 [33] | |||

| Marinova, 2014 [22] | ||||

| Treatment | • Decrease of nightmare frequency and anxiety after IRT intervention in MDD patients | Thünker, 2012 [34] | ||

| • Improvement of nightmare frequency inn 36 MDD patients after four sessions of EMDR | Woo, 2014 [35] | |||

| Evolution | • Patients with frequent nightmares ** were less in remission at four years than those without nightmares | Li, 2012 [32] | ||

| Mania | • Three patients had nightmares as prodromal symptoms of their first manic episode | Agargun, 2003 [36] | ||

| Psychotic disorders | Frequency | • Nightmares are more frequent in patient with schizophrenia than in healthy controls | Lusignan, 2009 [37] | |

| Michels, 2014 [38] | ||||

| • Frequency of frequent nightmares ** ranging from 9 to 55% | Sheaves, 2015 [39] | |||

| Chiu, 2016 [40] | ||||

| Li, 2016 [41] | ||||

| • Comorbid insomnia and nightmares are frequent in schizophrenia ∘ Patients with frequent nightmares ** were more likely to report frequentinsomnia ∘ Patients with frequent insomnia were more likely to have comorbid nightmares |

Li, 2016 [41] | |||

| • Nightmares are the second most frequent sleep disorder, after insomnia, in patients with schizophrenia. | Reeve, 2018 [42] | |||

| Symptoms | • Same themes of delusion and hallucination than in nightmares preceding psychotic decompensation (two reports) | Levin, 1998 [43] | ||

| Fennig, 1992 [44] | ||||

| • No significant correlations between depressive symptoms (assessed with BDI) and nightmare frequency • No significant correlations between psychotic symptoms (assessed with PANNS) and nightmare frequency |

Michels, 2014 [38] | |||

| • Nightmare distress, rather than frequency, is the best marker for the association between nightmares and daytime impairment: significant correlations between nightmare distress and delusional severity, depression, anxiety, and stress. | Sheaves, 2015 [39] | |||

| Suicide | • Patients with frequent nightmares ** have more lifetime of suicide history and increase risk of suicide attempts | Li, 2016 [41] | ||

| Treatment | • Efficacy of treatment by desensitization (one report) • Improvement of IRT on emotional response, not on nightmare frequency |

Shorkey, 1974 [45] | ||

| Sheaves, 2015 [46] | ||||

| • Imagery focused cognitive behavioral therapy: large effect size reductions in nightmares and insomnia post treatment (4 weeks) | Sheave, 2019 [47] | |||

| Comparing studies | Frequency | • Significantly more frequent in psychiatric patients (schizophrenia and MDD) than healthy controls • No significant differences between patients with schizophrenia and MDD |

Mume, 2009 [25] | |

| Suicide | • Higher suicidality scores (assessed with SUAS) in patients with frequent nightmares than without (MDD, schizophrenia) | Sjöström, 2007 [48] | ||

| • Patients with more than one past suicide attempts had more frequent nightmares**** than those with first suicide attempts | Sjöström, 2009 [19] | |||

| • Patients who reported monthly to weekly nightmares were younger and more likely to have been hospitalized for a recent suicide attempt. • Severe hopelessness more frequent in patients with nightmares |

Lamis, 2018 [49] | |||

Nightmares were found to be associated with higher suicidality in several studies, including suicidal ideations and attempts, in patients with mood disorders [23][36][30][31][34], or psychotic disorders [32]. In the general population, nightmares are also associated with a higher risk of suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, or death by suicide [19][20][21]. Moreover, several studies found frequent co-occurrence of insomnia and nightmares. Insomnia is one of the most common comorbid sleep disorders associated with psychiatric disorders [29][35], and is by itself associated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation in healthy and psychiatric populations [33]. Whereas insomnia is much more often screened for by psychiatrists, being a core symptom in the classification of some psychiatric disorders such as MDD or Bipolar disorder [16], the identification of nightmares is rare and is not included in mood or psychotic disorders classification. In this context, practitioners frequently consider nightmares and disturbing dreams as secondary symptoms, with no predicting or therapeutic relevance. However, even if most of the studies assessing nightmares and suicide are cohorts or case series, and that controlled studies are needed to clarify the role of nightmares on suicidal behavior, the present review suggests that patients should be systematically screened for recurrent or frequent nightmares, as they are both very frequent and seem to be associated with a higher risk of suicide [15][45][44][32][43].The correlation between nightmares and intensity of symptoms in mood disorders or psychotic disorders is not clear. Indeed, rather than nightmare frequency, nightmare distress may be more specifically associated with psychotic and depressive symptoms [28]. No studies have reported relationships between nightmare distress and depressive symptoms in patients with MDD, nor the relationship between nightmare distress and suicidality in patients with MDD or psychotic disorders. In the general population, nightmares have been associated with hallucinatory experiences [37] and with psychotic-like experiences [38][46][39][40][41][29][35][33][43][37][42].We decided to exclude all studies with patients under 18 years old because nightmares are more common in children and teenagers, and to avoid potential confusion factors. Nevertheless, one longitudinal study [47] interestingly found that nightmares at 12 years old were a significant predictor of psychotic experiences at 18 years old, after adjustment for possible confounders. This report is in line with our observations previously mentioned. Moreover, Michels et al. found that ARMS patients had more frequent nightmares than healthy controls [48], suggesting that nightmares may be present at a very early stage of the disease.The exact pathophysiology of nightmares in patients with mood and psychotic disorders is not entirely known. In a recent review, Gieselman et al. hypothesized the etiology of nightmares by hyperarousal and impaired fear extinction, with facilitating factors such as traumatic experiences and childhood adversity, trait susceptibility, maladaptive cognitive factors, and physiological factors [49]. Levin et al. proposed that nightmares reflect problems with the fear extinction function of dreaming [10]. Schredl et al. propose that certain nightmare themes, such as suicide, are of particular interest because they may be related to the psychopathology of waking life [50]. Further studies are expected to better unravel these physio-pathologies and specificities in psychiatric disorders, since nightmares in the context of trauma, stress, delirium, anxiety, or depressed mood may have different pathways and causes.

2.1. Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Suicide, which is the first cause of death among young people, is associated with several modifiable or non-modifiable risk factors, so it is important to be able to identify and manage [17]. Nightmares have been identified as one of the modifiable risk factors for suicide, with specific treatments, such as Image Rehearsal Therapy or Systematic Desensitization and Progressive Deep Muscle Relaxation training for treatment of idiopathic nightmares, or Prazosin if nightmares are associated with of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) [49][51]. Furthermore, as mentioned above, nightmares may be associated with early stages of psychotic or mood disorders, and its treatment may prevent the conversion to a full psychiatric disorder.

2.2. Limitations

This work clearly emphasizes a need to use standardized definitions of nightmares across studies, as we observed a lack of consensus criterion. Indeed, “frequent nightmare” was differently defined from one study to another, and sometimes not defined at all. With our code with asterisks (from * to **** when no definitions were proposed, see our methods), we tried to clarify this issue. We plead for standardized use of either the DSM-5 definition or systematic use of published questionnaires such as the Mannheim Dream Questionnaire (MADRE) [51]. DSM-5 defines a mild nightmare disorder as less than one episode per week on average, a moderate disorder as one or more episodes per week, but less than nightly, and a severe disorder as nightly episodes. An acute episode has a duration of 1 month or less, a sub-acute episode a duration between 1 to 6 months, and chronic nightmares endure for 6 months or longer (APA, 2013). Instruments to assess nightmare frequency and nightmare distress exist such as the Nightmare Frequency Questionnaire (NFQ) [52] or the MADRE [51]. The use of such instruments should be more generalized.

Some caveats and limitations of the existing scientific literature reviewed here should be emphasized. First, most studies of nightmares and mood disorders [53] assessed major depressive disorders (MDD), without any information about the unipolar of bipolar subtype of depression. This could bias results; for example, Marinova et al. [22] found a difference in the frequency of nightmares between unipolar and bipolar depression. Patients with unipolar depression and nightmares were more likely to have suicidal thoughts than those without nightmares; this difference was not found in patients with bipolar disorder (although this was a smaller group with underpowered statistics). Second, patients with PTSD or recent trauma were either not screened, nor always excluded from the studies. Yet nightmares are one of the mains symptoms of PTSD and stress-related disorders. This may have been a confounding factors in reported studies [38][39]. Third, there was no information of comorbid personality disorders; as in PTSD it may have been a confounding factor, as it is known that some personality disorders such as borderline personality are more associated with nightmares [2]. Fourth, most cohort studies examined the frequency of nightmares in their patients and looked for an association with suicidality. A significant majority did not report information on the severity of psychiatric symptoms. Patients who had more frequent nightmares were more likely to have suicidal thoughts or attempts but may also have had a higher intensity in their symptoms, which may have led to higher suicidality. Fifth, there was little information about the distinction between bad dreams/nightmares in reported studies. Nightmares are different from bad dreams since nightmares awaken the sleeper [10]. Sixth, only few studies mentioned their patient medication. However, nightmares have been found as being a side effect of some antipsychotics and antidepressant treatments, and so may have been a confounding factor as well [54]. Finally, all the studies were based on clinical evaluation (self-report nightmares or clinician interview), which can have led to a memory bias. There were no laboratory examinations of nightmares with more objective measures (except in the study of Lusignan et al. [55], who explored dreams and not nightmares).

2. Related Studies