Premature termination codons (PTCs) are stop codons arising from nonsense variants converting a sense codon into a termination signal, i.e. UAA, UAG or UGA. PTCs arising from mutations may, at low frequency, be misrecognized and result in PTC suppression, named ribosome readthrough, with production of full-length proteins through the insertion of a subset of amino acids. Since some drugs have been identified as readthrough inducers, this fidelity drawback has been explored as a therapeutic approach in several models of human diseases caused by nonsense mutations.

- nonsense mutations

- ribosome readthrough

- premature termination codon

Note:All the information in this draft can be edited by authors. And the entry will be online only after authors edit and submit it.

1. Ribosome Fidelity and Translation Termination

The translation of mRNA is a ribosome-catalyzed process leading to the synthesis of a polypeptide chain driven by the correct base pairing between mRNA codons and aminoacyl-tRNAs (aa-tRNAs) anticodons [1,2][1][2]. This biological event consists of three main phases, namely initiation, elongation, and termination.

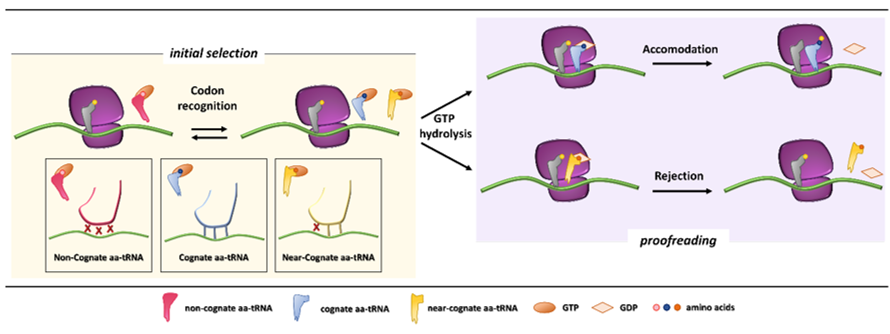

In the first phases of the translation process, interaction among mRNA, the initiator tRNA (placed in the ribosome P site), translation initiation factors, and the small ribosome subunit leads to the recruitment of the large subunit and formation of the initiation complex. Then, a process of aa-tRNA sampling occurs at each mRNA codon during the elongation phase. Each aa-tRNA enters the ribosomal A site as a ternary complex with a GTPase elongation factor (EF-Tu in prokaryotes and eEF1A in eukaryotes) and a GTP molecule. During this phase, the ribosome discriminates with high fidelity the cognate from non-cognate or near-cognate ternary complexes through two strategies, namely initial selection and proofreading. Both steps, separated by the irreversible hydrolysis of GTP, rely on the different stability of codon-anticodon matches [3,4][3][4] (Figure 1).

Initial selection allows for an efficient rejection of non-cognate aa-tRNAs on the basis of two out of three mismatches in the codon-anticodon duplexes, which leads to the dissociation of the incorrect aa-tRNA ternary complex with no costs in terms of GTP [5]. This kinetic mechanism alone is not enough to distinguish between cognate and near-cognate aa-tRNA complexes. Indeed, interactions of decoding center elements, located within the prokaryotic (16S) or eukaryotic (18S) rRNA, with both mRNA codon and tRNA anticodon are necessary to increase ribosome accuracy [6,7][6][7]. The ribosome fidelity during translation has been described in prokaryotes, but it is similar in eukaryotes. In particular, when a ternary complex enters the ribosomal A site, the binding of a cognate aa-tRNA anticodon to a mRNA codon induces two conserved adenines, A1492 and A1493 (prokaryote numbering), to flip out of an internal loop of helix 44 in 16S rRNA. Moreover, also the universally conserved G530 switches from the syn to the anti-conformation. This new arrangement enables the two key adenines to interact through hydrogen bonds with the first and second base pairs of the codon-anticodon helix, while the G530 interacts with the second anticodon position and the third codon position. As a result, the induced changes lead to the discrimination between correct Watson–Crick geometry, due to standard base pairing, at the first and second codon positions, whereas the third “wobble” base pair may accommodate other non-standard geometries [1,8][1][8]. Therefore, the recognition of the cognate aa-tRNA causes a local conformational change in the decoding site eliciting a transition from an open to a closed form of the small ribosomal subunit ensuring the subsequent hydrolysis of GTP [9]. Although it has been defined how recognition of a cognate aa-tRNA occurs, it is still unclear what the entry of near cognate aa-tRNA in ribosomal A site entails. One hypothesis is that the decoding site does not sense a correct Watson–Crick codon-anticodon base pairing, with the lack of stabilization for the near-cognate complex and its preferential rejection. Furthermore, structural studies reveal that binding of a near-cognate aa-tRNA does not induce the closed conformation of the small subunit, which rather remains in an open or partially-closed conformation [10]. However, it seems quite clear that a near-cognate aa-tRNA escapes from the initial selection step when a mismatch in the codon-anticodon helix mimics a Watson–Crick geometry [11–13][11][12][13].

Figure 1. Initial selection and proofreading activity of the translating ribosome. The insertion of cognate or near-cognate, as well as the rejection of non-cognate, aa-tRNAs is exerted by the ribosome during the initial selection step (left panel, with codon-anticodon interactions depicted in the boxes below). Upon GTP hydrolysis, the cognate aa-tRNA is efficiently accommodated, with formation of peptide bond and progression of protein synthesis with a new aa-tRNA selection step (right panel, upper part). The presence of a near-cognate aa-tRNA, which fails to be accommodated, results in rejection of the aa-tRNA through a proofreading step (right panel, lower part).

After codon recognition, which leads to the closed conformation of the small ribosomal subunit, a series of rearrangements occur in the aa-tRNA, leading to activation of the elongation factor GTPase. The hydrolysis of GTP consists of the docking of the elongation factor GTPase into the sarcin-ricin loop (SRL) within the large ribosomal subunit [8]. It has been demonstrated that, through local conformational changes in the small ribosomal subunit, the binding of a cognate aa-tRNA accelerates GTP hydrolysis in comparison with a near-cognate aa-tRNA [14,15][14][15]. Following the detachment of the GDP-bound elongation factor, an accommodation step of the aa-tRNA takes place, the mechanism of which can explain how the aa-tRNA proofreading occurs. The aa-tRNA moves into the peptidyl-transferase center, located within the large ribosomal subunit, through reversible fluctuations of its elbow region, acceptor arm and 3′CCA end from A to P site [15,16][15][16]. It seems that a cognate aa-tRNA accommodates more rapidly than a near-cognate aa-tRNA due to a more stable codon-anticodon base pairing during the proofreading step. On the other hand, unfavorable Watson–Crick geometry and weak codon-anticodon interactions probably facilitate rejection of a near-cognate aa-tRNA, which circumvented the initial selection step [12,17][12][17]. Overall, ribosome fidelity strategies strictly monitor the aa-tRNA selection during the translation process.

The final phase, translation termination, is triggered when a stop codon (UAA, UAG, UGA) enters the ribosomal A site [18,19][18][19]. In general, extra-ribosomal proteins, named release factors (RFs), are recruited to promote the release of the nascent polypeptide [20]. In eukaryotes, an essential role is played by the two main effectors eRF1 and eRF3. The eRF1 protein consists of three domains, namely an N-terminal domain directly recognizing all stop codons, a middle domain containing a conserved GGQ (Gly-Gly-Gln) motif involved into stimulation of polypeptide chain hydrolysis, and a C-terminal domain that binds eRF3 [21]. The second release factor, eRF3, consists of different domains, among which the most relevant is the G domain, which binds GTP and assists the termination process through GTP hydrolysis [22]. Similarly to the elongation phase, when a stop codon enters the ribosomal A site, a process of aa-tRNA ternary complex sampling occurs. At the same time another ternary complex, composed of eRF1, eRF3, and GTP, competes for stop codons recognition [23], driven by the N-terminal domain of eRF1 that establishes multiple contacts with the 40S subunit. The key step of GTP hydrolysis, prevented by the middle domain of eRF1 during formation of the pre-termination complex, is triggered by interactions involving eRF3 and the SRL [24]. Upon GTP hydrolysis, the positioning of eRF1 GGQ motif into the peptidyl transferase center stimulates the hydrolysis of the ester bond between tRNA and the polypeptide chain [25].

2. Nonsense Mutations and mRNA Quality Control

A relevant detrimental effect on protein synthesis may be exerted by nonsense mutations, which account for 11% of all gene alterations responsible for inherited human genetic diseases [26]. Nonsense mutations are defined as single-base pair substitutions affecting gene coding regions, which convert an mRNA sense codon into an in-frame premature termination codon (PTC). The impairment of gene expression due to PTC-containing transcripts is related to (i) the degradation of truncated proteins, with decreased stability or loss-of-function features, resulting from premature termination of translation, or (ii) the reduction in the steady-state level of cytoplasmic mRNA by the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) quality control system [27–29][27][28][29]. However, it has been demonstrated that 5–25% of aberrant mRNAs might escape NMD, thus producing a truncated protein that, in autosomal disorders, might interfere with the wild-type protein function and give rise to dominant-negative effects [30].

In particular, the NMD mechanism degrades PTC-bearing transcripts through the interplay of cis and trans factors. The first signal is provided by the exon junction complexes (EJCs), a multiprotein set deposited ∼20–24 nucleotides upstream of each exon-exon junction as a marker of the occurrence of splicing events [31–33][31][32][33]. It has been shown that PTC-bearing mRNAs bound to the cap-binding complex (CBC, consisting of CBP80-CBP20) can be recognized as NMD substrates during the so-called pioneer round of translation, namely a first translational cycle in which the ribosome performs an mRNA scan. During the pioneer round of translation, if the stop codon is located at the 3′ of the coding region, typical of natural stop signals, the ribosome displaces all EJCs, which allows the subsequent replacement of CBC with eIF4E and makes the mRNA immune to NMD. Conversely, if the transcript harbors a PTC, causing ribosome stalling, the NMD pathway is engaged due to the presence of downstream EJCs that cannot be removed [34]. Accordingly, immuno-purification studies showed that eIF4E-bound mRNAs were not associated with factors required for NMD, thus supporting that NMD takes place during the pioneer round of translation [35] (Figure 2).

Among the proteins involved in mRNA decay, the major orchestrator is Upf1, an ATP-dependent RNA helicase that is recruited on the PTC together with eRF1, eRF3, and SMG1 (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related protein kinase) in the so-called SURF (SMG1-Upf1-eRF1-eRF3) complex [36]. Other components are required for the NMD activation, such as Upf3 or 3X, which are generally associated with EJCs in the nucleus, and Upf2, which is assembled to EJCs after mRNA export to the cytoplasm [35,37,38][35][37][38]. Once the PTC-bearing transcript is identified by the NMD machinery, several rearrangements and conformational changes occur, including the Upf1-mediated formation of the decay-inducing complex formation (DECID) [39[39][40],40], which leads to degradation of the tagged mRNA in a process driven by phosphorylated Upf1 [41,42][41][42]. Finally, the NMD factors are disassembled by Upf1, which in turn is converted to its unphosphorylated form [43].

Figure 2. Fates of normal or PTC-bearing mRNA transcripts during the first step of translation. The splicing of pre-mRNA into the nucleus results in a mature mRNA transcript bound to exon-junction complexes (EJCs) as well as other key components such as the Upf3 (in the nucleus) and Upf2 (in the cytoplasm) proteins. Once transported into the cytoplasm, the mRNA undergoes a first (pioneer) round of translation. In normal conditions, the ribosome displaces all EJCs, resulting in the replacement of CBC with eIF4E, mRNA circularization and protein synthesis, which proceeds until the natural termination codon (NTC) is reached. If a premature termination codon (PTC) is present, EJCs are not efficiently removed by the ribosome, resulting in recruitment of eRF1, eRF3, Upf1 and the SMG1 kinase, which leads to Upf1 phosphorylation and degradation of the UPF1-tagged mRNA.

References

- Ogle, J.M.; Brodersen, D.E.; Clemons, W.M.; Tarry, M.J.; Carter, A.P.; Ramakrishnan, V. Recognition of cognate transfer RNA by the 30S ribosomal subunit. Science 2001, 292, 897–902, doi:10.1126/science.1060612.

- Rodnina, M.V.; Wintermeyer, W. Ribosome fidelity: tRNA discrimination, proofreading and induced fit. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2001, 26, 124–130, doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01737-0.

- Hopfield, J.J. Kinetic proofreading: a new mechanism for reducing errors in biosynthetic processes requiring high specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1974, 71, 4135–4139, doi:10.1073/pnas.71.10.4135.

- Ruusala, T.; Ehrenberg, M.; Kurland, C.G. Is there proofreading during polypeptide synthesis? EMBO J 1982, 1, 741–745, doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01240.x.

- Pape, T.; Wintermeyer, W.; Rodnina, M. Induced fit in initial selection and proofreading of aminoacyl-tRNA on the ribosome. EMBO J 1999, 18, 3800–3807, doi:10.1093/emboj/18.13.3800.

- Yarus, M. Proofreading, NTPases and translation: constraints on accurate biochemistry. Trends Biochem Sci 1992, 17, 130–133, doi:10.1016/0968-0004(92)90320-9.

- Wohlgemuth, I.; Pohl, C.; Rodnina, M.V. Optimization of speed and accuracy of decoding in translation. EMBO J 2010, 29, 3701–3709, doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.229.

- Fischer, N.; Neumann, P.; Bock, L.V.; Maracci, C.; Wang, Z.; Paleskava, A.; Konevega, A.L.; Schröder, G.F.; Grubmüller, H.; Ficner, R.; et al. The pathway to GTPase activation of elongation factor SelB on the ribosome. Nature 2016, 540, 80–85, doi:10.1038/nature20560.

- Ogle, J.M.; Murphy, F.V.; Tarry, M.J.; Ramakrishnan, V. Selection of tRNA by the ribosome requires a transition from an open to a closed form. Cell 2002, 111, 721–732, doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01086-3.

- Agirrezabala, X.; Schreiner, E.; Trabuco, L.G.; Lei, J.; Ortiz-Meoz, R.F.; Schulten, K.; Green, R.; Frank, J. Structural insights into cognate versus near-cognate discrimination during decoding. EMBO J 2011, 30, 1497–1507, doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.58.

- Demeshkina, N.; Jenner, L.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. A new understanding of the decoding principle on the ribosome. Nature 2012, 484, 256–259, doi:10.1038/nature10913.

- Rozov, A.; Demeshkina, N.; Khusainov, I.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. Novel base-pairing interactions at the tRNA wobble position crucial for accurate reading of the genetic code. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10457, doi:10.1038/ncomms10457.

- Rozov, A.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. The ribosome prohibits the G•U wobble geometry at the first position of the codon-anticodon helix. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 6434–6441, doi:10.1093/nar/gkw431.

- Blanchard, S.C.; Gonzalez, R.L.; Kim, H.D.; Chu, S.; Puglisi, J.D. tRNA selection and kinetic proofreading in translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2004, 11, 1008–1014, doi:10.1038/nsmb831.

- Geggier, P.; Dave, R.; Feldman, M.B.; Terry, D.S.; Altman, R.B.; Munro, J.B.; Blanchard, S.C. Conformational sampling of aminoacyl-tRNA during selection on the bacterial ribosome. J Mol Biol 2010, 399, 576–595, doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.038.

- Polikanov, Y.S.; Starosta, A.L.; Juette, M.F.; Altman, R.B.; Terry, D.S.; Lu, W.; Burnett, B.J.; Dinos, G.; Reynolds, K.A.; Blanchard, S.C.; et al. Distinct tRNA Accommodation Intermediates Observed on the Ribosome with the Antibiotics Hygromycin A and A201A. Mol Cell 2015, 58, 832–844, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.014.

- Zaher, H.S.; Green, R. Hyperaccurate and error-prone ribosomes exploit distinct mechanisms during tRNA selection. Mol Cell 2010, 39, 110–120, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.009.

- Dever, T.E.; Green, R. The elongation, termination, and recycling phases of translation in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4, a013706, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a013706.

- Jackson, R.J.; Hellen, C.U.T.; Pestova, T.V. Termination and post-termination events in eukaryotic translation. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2012, 86, 45–93, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386497-0.00002-5.

- Schuller, A.P.; Green, R. Roadblocks and resolutions in eukaryotic translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 526–541, doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0011-4.

- Hellen, C.U.T. Translation Termination and Ribosome Recycling in Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018, 10, a032656, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a032656.

- Salas-Marco, J.; Bedwell, D.M. GTP hydrolysis by eRF3 facilitates stop codon decoding during eukaryotic translation termination. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 7769–7778, doi:10.1128/MCB.24.17.7769-7778.2004.

- Keeling, K.M.; Xue, X.; Gunn, G.; Bedwell, D.M. Therapeutics based on stop codon readthrough. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2014, 15, 371–394, doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153527.

- des Georges, A.; Hashem, Y.; Unbehaun, A.; Grassucci, R.A.; Taylor, D.; Hellen, C.U.T.; Pestova, T.V.; Frank, J. Structure of the mammalian ribosomal pre-termination complex associated with eRF1.eRF3.GDPNP. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 3409–3418, doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1279.

- Shao, S.; Murray, J.; Brown, A.; Taunton, J.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Hegde, R.S. Decoding Mammalian Ribosome-mRNA States by Translational GTPase Complexes. Cell 2016, 167, 1229-1240.e15, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.046.

- Mort, M.; Ivanov, D.; Cooper, D.N.; Chuzhanova, N.A. A meta-analysis of nonsense mutations causing human genetic disease. Hum Mutat 2008, 29, 1037–1047, doi:10.1002/humu.20763.

- Kuzmiak, H.A.; Maquat, L.E. Applying nonsense-mediated mRNA decay research to the clinic: progress and challenges. Trends Mol Med 2006, 12, 306–316, doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.05.005.

- Khajavi, M.; Inoue, K.; Lupski, J.R. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay modulates clinical outcome of genetic disease. Eur J Hum Genet 2006, 14, 1074–1081, doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201649.

- Behm-Ansmant, I.; Kashima, I.; Rehwinkel, J.; Saulière, J.; Wittkopp, N.; Izaurralde, E. mRNA quality control: an ancient machinery recognizes and degrades mRNAs with nonsense codons. FEBS Lett 2007, 581, 2845–2853, doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.027.

- Isken, O.; Maquat, L.E. Quality control of eukaryotic mRNA: safeguarding cells from abnormal mRNA function. Genes Dev 2007, 21, 1833–1856, doi:10.1101/gad.1566807.

- Le Hir, H.; Izaurralde, E.; Maquat, L.E.; Moore, M.J. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20-24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J 2000, 19, 6860–6869, doi:10.1093/emboj/19.24.6860.

- Lejeune, F.; Li, X.; Maquat, L.E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in mammalian cells involves decapping, deadenylating, and exonucleolytic activities. Mol Cell 2003, 12, 675–687, doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00349-6.

- Ballut, L.; Marchadier, B.; Baguet, A.; Tomasetto, C.; Séraphin, B.; Le Hir, H. The exon junction core complex is locked onto RNA by inhibition of eIF4AIII ATPase activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005, 12, 861–869, doi:10.1038/nsmb990.

- Popp, M.W.-L.; Maquat, L.E. Organizing principles of mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Annu Rev Genet 2013, 47, 139–165, doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133424.

- Lejeune, F.; Ishigaki, Y.; Li, X.; Maquat, L.E. The exon junction complex is detected on CBP80-bound but not eIF4E-bound mRNA in mammalian cells: dynamics of mRNP remodeling. EMBO J 2002, 21, 3536–3545, doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf345.

- Kashima, I.; Yamashita, A.; Izumi, N.; Kataoka, N.; Morishita, R.; Hoshino, S.; Ohno, M.; Dreyfuss, G.; Ohno, S. Binding of a novel SMG-1-Upf1-eRF1-eRF3 complex (SURF) to the exon junction complex triggers Upf1 phosphorylation and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 355–367, doi:10.1101/gad.1389006.

- Kim, V.N.; Kataoka, N.; Dreyfuss, G. Role of the nonsense-mediated decay factor hUpf3 in the splicing-dependent exon-exon junction complex. Science 2001, 293, 1832–1836, doi:10.1126/science.1062829.

- Lykke-Andersen, J.; Shu, M.D.; Steitz, J.A. Communication of the position of exon-exon junctions to the mRNA surveillance machinery by the protein RNPS1. Science 2001, 293, 1836–1839, doi:10.1126/science.1062786.

- Yamashita, A.; Izumi, N.; Kashima, I.; Ohnishi, T.; Saari, B.; Katsuhata, Y.; Muramatsu, R.; Morita, T.; Iwamatsu, A.; Hachiya, T.; et al. SMG-8 and SMG-9, two novel subunits of the SMG-1 complex, regulate remodeling of the mRNA surveillance complex during nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev 2009, 23, 1091–1105, doi:10.1101/gad.1767209.

- Hwang, J.; Sato, H.; Tang, Y.; Matsuda, D.; Maquat, L.E. UPF1 association with the cap-binding protein, CBP80, promotes nonsense-mediated mRNA decay at two distinct steps. Mol Cell 2010, 39, 396–409, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.004.

- Kurosaki, T.; Maquat, L.E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans at a glance. J Cell Sci 2016, 129, 461–467, doi:10.1242/jcs.181008.

- Okada-Katsuhata, Y.; Yamashita, A.; Kutsuzawa, K.; Izumi, N.; Hirahara, F.; Ohno, S. N- and C-terminal Upf1 phosphorylations create binding platforms for SMG-6 and SMG-5:SMG-7 during NMD. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 1251–1266, doi:10.1093/nar/gkr791.

- Chiu, S.-Y.; Serin, G.; Ohara, O.; Maquat, L.E. Characterization of human Smg5/7a: a protein with similarities to Caenorhabditis elegans SMG5 and SMG7 that functions in the dephosphorylation of Upf1. RNA 2003, 9, 77–87, doi:10.1261/rna.2137903.

References

- Ogle, J.M.; Brodersen, D.E.; Clemons, W.M.; Tarry, M.J.; Carter, A.P.; Ramakrishnan, V. Recognition of cognate transfer RNA by the 30S ribosomal subunit. Science 2001, 292, 897–902, doi:10.1126/science.1060612.

- Rodnina, M.V.; Wintermeyer, W. Ribosome fidelity: tRNA discrimination, proofreading and induced fit. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2001, 26, 124–130, doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01737-0.

- Hopfield, J.J. Kinetic proofreading: a new mechanism for reducing errors in biosynthetic processes requiring high specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1974, 71, 4135–4139, doi:10.1073/pnas.71.10.4135.

- Ruusala, T.; Ehrenberg, M.; Kurland, C.G. Is there proofreading during polypeptide synthesis? EMBO J 1982, 1, 741–745, doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01240.x.

- Pape, T.; Wintermeyer, W.; Rodnina, M. Induced fit in initial selection and proofreading of aminoacyl-tRNA on the ribosome. EMBO J 1999, 18, 3800–3807, doi:10.1093/emboj/18.13.3800.

- Yarus, M. Proofreading, NTPases and translation: constraints on accurate biochemistry. Trends Biochem Sci 1992, 17, 130–133, doi:10.1016/0968-0004(92)90320-9.

- Wohlgemuth, I.; Pohl, C.; Rodnina, M.V. Optimization of speed and accuracy of decoding in translation. EMBO J 2010, 29, 3701–3709, doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.229.

- Fischer, N.; Neumann, P.; Bock, L.V.; Maracci, C.; Wang, Z.; Paleskava, A.; Konevega, A.L.; Schröder, G.F.; Grubmüller, H.; Ficner, R.; et al. The pathway to GTPase activation of elongation factor SelB on the ribosome. Nature 2016, 540, 80–85, doi:10.1038/nature20560.

- Ogle, J.M.; Murphy, F.V.; Tarry, M.J.; Ramakrishnan, V. Selection of tRNA by the ribosome requires a transition from an open to a closed form. Cell 2002, 111, 721–732, doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01086-3.

- Agirrezabala, X.; Schreiner, E.; Trabuco, L.G.; Lei, J.; Ortiz-Meoz, R.F.; Schulten, K.; Green, R.; Frank, J. Structural insights into cognate versus near-cognate discrimination during decoding. EMBO J 2011, 30, 1497–1507, doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.58.

- Demeshkina, N.; Jenner, L.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. A new understanding of the decoding principle on the ribosome. Nature 2012, 484, 256–259, doi:10.1038/nature10913.

- Rozov, A.; Demeshkina, N.; Khusainov, I.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. Novel base-pairing interactions at the tRNA wobble position crucial for accurate reading of the genetic code. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10457, doi:10.1038/ncomms10457.

- Rozov, A.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. The ribosome prohibits the G•U wobble geometry at the first position of the codon-anticodon helix. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 6434–6441, doi:10.1093/nar/gkw431.

- Blanchard, S.C.; Gonzalez, R.L.; Kim, H.D.; Chu, S.; Puglisi, J.D. tRNA selection and kinetic proofreading in translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2004, 11, 1008–1014, doi:10.1038/nsmb831.

- Geggier, P.; Dave, R.; Feldman, M.B.; Terry, D.S.; Altman, R.B.; Munro, J.B.; Blanchard, S.C. Conformational sampling of aminoacyl-tRNA during selection on the bacterial ribosome. J Mol Biol 2010, 399, 576–595, doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.038.

- Polikanov, Y.S.; Starosta, A.L.; Juette, M.F.; Altman, R.B.; Terry, D.S.; Lu, W.; Burnett, B.J.; Dinos, G.; Reynolds, K.A.; Blanchard, S.C.; et al. Distinct tRNA Accommodation Intermediates Observed on the Ribosome with the Antibiotics Hygromycin A and A201A. Mol Cell 2015, 58, 832–844, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.014.

- Zaher, H.S.; Green, R. Hyperaccurate and error-prone ribosomes exploit distinct mechanisms during tRNA selection. Mol Cell 2010, 39, 110–120, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.009.

- Dever, T.E.; Green, R. The elongation, termination, and recycling phases of translation in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4, a013706, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a013706.

- Jackson, R.J.; Hellen, C.U.T.; Pestova, T.V. Termination and post-termination events in eukaryotic translation. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2012, 86, 45–93, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386497-0.00002-5.

- Schuller, A.P.; Green, R. Roadblocks and resolutions in eukaryotic translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 526–541, doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0011-4.

- Hellen, C.U.T. Translation Termination and Ribosome Recycling in Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018, 10, a032656, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a032656.

- Salas-Marco, J.; Bedwell, D.M. GTP hydrolysis by eRF3 facilitates stop codon decoding during eukaryotic translation termination. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 7769–7778, doi:10.1128/MCB.24.17.7769-7778.2004.

- Keeling, K.M.; Xue, X.; Gunn, G.; Bedwell, D.M. Therapeutics based on stop codon readthrough. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2014, 15, 371–394, doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153527.

- des Georges, A.; Hashem, Y.; Unbehaun, A.; Grassucci, R.A.; Taylor, D.; Hellen, C.U.T.; Pestova, T.V.; Frank, J. Structure of the mammalian ribosomal pre-termination complex associated with eRF1.eRF3.GDPNP. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 3409–3418, doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1279.

- Shao, S.; Murray, J.; Brown, A.; Taunton, J.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Hegde, R.S. Decoding Mammalian Ribosome-mRNA States by Translational GTPase Complexes. Cell 2016, 167, 1229-1240.e15, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.046.

- Mort, M.; Ivanov, D.; Cooper, D.N.; Chuzhanova, N.A. A meta-analysis of nonsense mutations causing human genetic disease. Hum Mutat 2008, 29, 1037–1047, doi:10.1002/humu.20763.

- Kuzmiak, H.A.; Maquat, L.E. Applying nonsense-mediated mRNA decay research to the clinic: progress and challenges. Trends Mol Med 2006, 12, 306–316, doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.05.005.

- Khajavi, M.; Inoue, K.; Lupski, J.R. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay modulates clinical outcome of genetic disease. Eur J Hum Genet 2006, 14, 1074–1081, doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201649.

- Behm-Ansmant, I.; Kashima, I.; Rehwinkel, J.; Saulière, J.; Wittkopp, N.; Izaurralde, E. mRNA quality control: an ancient machinery recognizes and degrades mRNAs with nonsense codons. FEBS Lett 2007, 581, 2845–2853, doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.027.

- Isken, O.; Maquat, L.E. Quality control of eukaryotic mRNA: safeguarding cells from abnormal mRNA function. Genes Dev 2007, 21, 1833–1856, doi:10.1101/gad.1566807.

- Le Hir, H.; Izaurralde, E.; Maquat, L.E.; Moore, M.J. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20-24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J 2000, 19, 6860–6869, doi:10.1093/emboj/19.24.6860.

- Lejeune, F.; Li, X.; Maquat, L.E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in mammalian cells involves decapping, deadenylating, and exonucleolytic activities. Mol Cell 2003, 12, 675–687, doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00349-6.

- Ballut, L.; Marchadier, B.; Baguet, A.; Tomasetto, C.; Séraphin, B.; Le Hir, H. The exon junction core complex is locked onto RNA by inhibition of eIF4AIII ATPase activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005, 12, 861–869, doi:10.1038/nsmb990.

- Popp, M.W.-L.; Maquat, L.E. Organizing principles of mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Annu Rev Genet 2013, 47, 139–165, doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133424.

- Lejeune, F.; Ishigaki, Y.; Li, X.; Maquat, L.E. The exon junction complex is detected on CBP80-bound but not eIF4E-bound mRNA in mammalian cells: dynamics of mRNP remodeling. EMBO J 2002, 21, 3536–3545, doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf345.

- Kashima, I.; Yamashita, A.; Izumi, N.; Kataoka, N.; Morishita, R.; Hoshino, S.; Ohno, M.; Dreyfuss, G.; Ohno, S. Binding of a novel SMG-1-Upf1-eRF1-eRF3 complex (SURF) to the exon junction complex triggers Upf1 phosphorylation and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 355–367, doi:10.1101/gad.1389006.

- Kim, V.N.; Kataoka, N.; Dreyfuss, G. Role of the nonsense-mediated decay factor hUpf3 in the splicing-dependent exon-exon junction complex. Science 2001, 293, 1832–1836, doi:10.1126/science.1062829.

- Lykke-Andersen, J.; Shu, M.D.; Steitz, J.A. Communication of the position of exon-exon junctions to the mRNA surveillance machinery by the protein RNPS1. Science 2001, 293, 1836–1839, doi:10.1126/science.1062786.

- Yamashita, A.; Izumi, N.; Kashima, I.; Ohnishi, T.; Saari, B.; Katsuhata, Y.; Muramatsu, R.; Morita, T.; Iwamatsu, A.; Hachiya, T.; et al. SMG-8 and SMG-9, two novel subunits of the SMG-1 complex, regulate remodeling of the mRNA surveillance complex during nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev 2009, 23, 1091–1105, doi:10.1101/gad.1767209.

- Hwang, J.; Sato, H.; Tang, Y.; Matsuda, D.; Maquat, L.E. UPF1 association with the cap-binding protein, CBP80, promotes nonsense-mediated mRNA decay at two distinct steps. Mol Cell 2010, 39, 396–409, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.004.

- Kurosaki, T.; Maquat, L.E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans at a glance. J Cell Sci 2016, 129, 461–467, doi:10.1242/jcs.181008.

- Okada-Katsuhata, Y.; Yamashita, A.; Kutsuzawa, K.; Izumi, N.; Hirahara, F.; Ohno, S. N- and C-terminal Upf1 phosphorylations create binding platforms for SMG-6 and SMG-5:SMG-7 during NMD. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 1251–1266, doi:10.1093/nar/gkr791.

- Chiu, S.-Y.; Serin, G.; Ohara, O.; Maquat, L.E. Characterization of human Smg5/7a: a protein with similarities to Caenorhabditis elegans SMG5 and SMG7 that functions in the dephosphorylation of Upf1. RNA 2003, 9, 77–87, doi:10.1261/rna.2137903.