Skew polynomial rings used to be, especially during the 1970’s and 1980’s, a popular topic of the modern abstract Algebra with great theoretical interest. The researchers’ attention about them has renewed recently, due to the important applications that they have found to the study of Quantum Groups and to Cryptography. The present work studies a special class of iterated skew polynomial rings over a ring R, defined with respect to a finite set of pairwise commuting derivations of R.

- Skew polynomial rings (SPR),terated SPR (ISPR),derivations

1. Introduction

The history of Science shows that progress in mathematics is achieved in two ways. The first way is connected to the effort of applying mathematics to solve real world problems, or problems of the everyday life. Frequently, however, the already known mathematical theories are proved to be not suitable or enough to solve the corresponding problems. In such cases the scientists are forced to develop new mathematics in order to overcome the existing difficulties. Characteristic examples of this case are the recently developed theories of Fuzzy Sets [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][1] and of Chaotic Dynamics and Fractals [2][3], which have found important applications in many sectors of the human activity.

The second way of progress in mathematics concerns pure mathematical research, i.e. the process of “doing mathematics for mathematics". The amazing thing in this case, however, is that usually theories developed through pure mathematical research, find, sometimes many years after their initial appearance, successful and often unsuspected applications to real situations. As an example, the non-Euclidean Geometries, developed on a purely theoretical basis by Lobachevsky, Riemann and others during the 19th century (e.g. [4], Section 3) helped later Einstein to prove his famous Relativity Theory, which has replaced the Newton’s classical theory of gravity for the existing great masses and distances in the Universe (outside the Earth) [5]. Another example is the Knot theory, initiated from a false model for the description of the atom’s theory, which however proved later to be the key for understanding the basic mechanisms of the DNA!

Examples analogous to the previous two can be found in abundance in the history of mathematics. The Nobel Prize winner E.P. Winger has characterized this phenomenon as “the unreasonable effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”, a characterization which is widely known as the Winger’s enigma [4]. This phenomenon rises a question which has occupied for centuries, and still occupies, the interest of philosophers, mathematicians and other scientists: Is actually Mathematics INVENTED or DISCOVERED by humans? The great ancient Greek philosopher Plato introduced the idea of the existence of an abstract “Universe of Mathematics”, parts of which are eventually discovered by humans. His theory, usually referred as Platonism, despite the blows that has received during the centuries by the development of several mathematical theories and the opposite views of many other philosophers, social thinkers and scientists, has still many supporters in our times [4].

The present study focuses on Skew Polynomial Rings (SPRs), a topic of abstract Algebra which can be considered also as an example of the Winger’s enigma. SPR have been firstly introduced by Ore [6] in 1933 over a division ring R and that is why they are also called Ore extensions. Those rings were initially used as counter examples, but eventually a great attention was given to them and many papers were written, especially during the 1970’s and 1980’s, since it was realized that they have an important theoretical interest.

The researchers’ interest about SPRs has been renewed recently, because they have found two important applications. The first application is related to the use of quantum groups as a tool of Theoretical Physics. It is recalled that a quantum groups is a Hopf algebra having in addition a structure analogous to that of a Lee group [7]. It has been observed that most of these algebras can be expressed in the form of a SPR.

The second application concerns the use of SPRs in coding theory. More explicitly, Jatengaokar [8] studied in detail the structure of monomorphism skewed polynomial rings over semi-simple rings showing that they are direct sums of matrix rings. Jatengaokar’s structure theorem for SPRs has been recently used in coding theory to analyze the structure of certain convolutional codes. For the same purpose, Jatengaokar’s results hav [9].

The rest of the present article is organized as follows: Section 2 includes the definitions and some examples of SPRs and of Iterated SPRs (ISPRs), i.e. SPRs in finitely many variables. In Section 3 a special class of ISPRs is introduced over a ring R with respect to a finite set of pairwise commuting derivations of R, some important properties of the ISPRs of this class are presented, and examples are given. The paper closes with the final conclusions, which are stated in Section 4.

2. Skew Polynomial Rings

Let R be a ring with identity. In order to define a SPR over R, we extend the notion of a derivation of R as follows:

Definition 2.1: Let f and g be endomorphisms of R and let d: R R be a map satisfying, for all a, b in R, the properties:

- d(a+b)=d(a)+d(b)

- d(ab)= g(a)d(b)+d(a)f(b).

Then d is called a (f,g)-derivation of R.

If both f and g are identity maps, then d becomes a classical derivation of R. Also, if only g is the identity map, then d is called an f-derivation of R or a skew derivation of R defined with respect to f.

Let now f be a monomorphism of R and let d be an f-derivation of R. Then we define a SPR over R as follows:

Definition 2.2: Consider the set S of all polynomials in one variable, say x, over R. Define addition in S in the usual way and multiplication by the distributive law with respect to addition and by the by the rule

xr=f(r)x+d(r) (1).

Then it is straightforward to check that S becomes a ring, called a skew (or twisted) polynomial ring over R and denoted by R[x; f, d].

In Definition 2.2, f has been considered to be a monomorphism, and not a simple endomorphism of R, just to block the case for x to be a zero divisor of S. In fact, if there were r1 r2 in R such that f(r1)=f(r2), then by equation (1) we should have

x(r1-r2)=xr1-xr2=f(r1)x+d(r1)-[f(r2)x+d(r2)}=d(r1-r2).

Therefore, if r1-r2 is in the kernel of d, we should have x(r1-r2)=0.

If f is the identity map, then S is denoted by R[x; d] and is called a SPR of derivation type over R. Then equation (1) gives, for all r in R, that

xr = rx + d(r) (2).

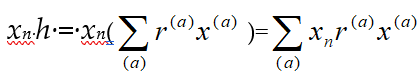

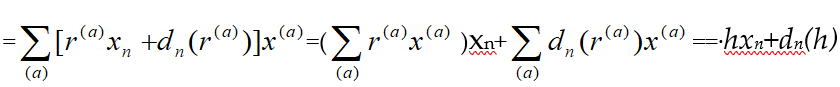

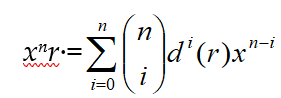

Using equation (2) and applying induction on n one finds, for all r in R and all positive integers n, that

Also, if d is the zero derivation of R, then the SPR S is denoted by R[x; f], where multiplication is defined, for all r in R, by the distributive law and the equation

xr = f(r)x (5)

Applying induction on n one finds from equation (5) that, for all r in R and all positive integers n, is

xnr = fn(r)xn (6)

Example 2.3: Let T[x1] be a polynomial ring over a ring T, then the SPR T[x1][x2; ] over T[x1] is called the first Weyl algebra over T and is denoted by A1(T). It becomes evident that the elements of A1(T) are polynomials in two variables x1 and x2 over T and multiplication, for all t in T, is defined by

x1t=tx1, x2t=tx2+ = tx2, x2x1=x1x2+ =x1x2+1 (4)

Next, following [10] one can define an ISPR over R as follows:

Definition 2.4: Let S1=R[x1; f1, d1] be a SPR over the ring R, where f1 is a monomorphism and d1 is a f1-derivation of R. Then, if f2 is a monomorphism and d2 is a f2-derivation of S1, the SPR S2=S1[x2; f2, d2] is called an ISPR over R and is denoted by S2=R[x1; f1, d1][x2; f2, d2].

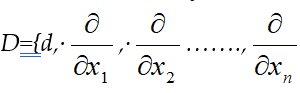

Keep the same notation and set S0=R. Consider the finite sets H={f1,f2,…,fn}, where fi is a monomorphism of Si-1 , and D={d1,d2,…dn}, where di is a fi-derivation of Si-1, for i=1,0,…,n. Then by induction one defines the ISPR Sn=R[x1; f1, d1][x2; f2, d2]….[xn; fn, dn] over R . In order to simplify our notation we shall denote this ring by Sn=R[x; H, D].

When all the elements of H are identity maps, then Sn is denoted by R[x; D] and is called an ISPR of derivation type over R. Also, when all the elements of D are zero derivations, then one obtains the ISPR Sn=R[x; H], which is defined with respect to the set H of endomorphisms of R.

Examples 2.5:

(i) The first Weyl algebra A1(T) over a ring T (Example 2.3) is an ISPR of derivation type in two variables over T of the form T[x1; d][x2, ], where d denotes the zero derivation of T. In this case T[x1; d] is the ordinary polynomial ring T[x1].

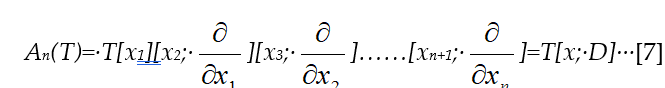

(ii) Set R= A1(T). Then the first Weyl algebra A1(R) over R is called the second Weyl algebra over T and is denoted by A2(T). Obviously we have that

A2(T)= A1[A1(T)]=T[x1][x2; ][x3; ].

(iii) Consider the set of all polynomials in n+1 variables, say x1,x2,…, xn,xn+1, over a ring T. Then the n-th Weyl algebra An(T) over T is defined by induction as An(T)=A1[An-1(T)]. Denote by d the zero derivation of T and set

3. On a Special Class of Iterated Skew Polynomial Rings of Derivation Type

In this section, given a finite set D of pairwise commuting derivations of R, we shall construct an ISPR R[x; D] of derivation type over R. For this, we need the following lemma:

Lemma 3.1: Let R be a ring, let d be a derivation of R, let S=R[x; d] be the SPR over R defined with respect to d, and let d1 be another derivation of R. Then d1 can be extended to a derivation of S by d1(x)=0, if, and only if, d1 commutes with d.

Proof: Assume first that d1 can be extended to a derivation of S by d1(x)=0. Then, for all r in R, we have that d1(xr)=d1(x)r+xd1(r)= xd1(r) (8)

Then, by equation (2) we have that d1(xr)=d1[rx+d(r)]=d1(rx)+ d1[d(r)]

= d1(r)x+ d1(x)+ d1[d(r)] =d1(r)x+d1[d(r)] and xd1(r)=d1(r)x+d[d1(r)]. Therefore (8) gives that d1[d(r)]= d[d1(r)] for all r in R, which shows that d1od = dod1.

Conversely assume that d1od= =dod1. Then, if d1 can be extended to a derivation of S, we must have, for all r in R, that d1(xr)= d1(x)r+ xd1(r) (9)

But, as before, we find that d1(xr)=d1(r)x+ d1(x)+ d1[d(r)] and xd1(r)=d1(r)x+d[d1(r)]. Therefore. (9) gives that d1(r)x+ d1(x)+ d1[d(r)]= d1(x)r+ d1(r)x+d[d1(r)] or d1(x)= d1(x)r, which is true for d1(x)=0.

We are ready now to prove the following theorem:

Theorem 3.2: Let R be a ring, and let D={d1,d2,….,dn} be a finite set of derivations of R. Set S0=R and denote by Si the set of all polynomials in variables, say x1, x2,…., xi, with coefficients in R, for i=0,1,2,….,n. Define in Sn addition in the usual way and multiplication by the distributive law with respect to addition and by the rules

xir=rxi+di(r) for all r in R, xixj=xjxi for i,j=1,2,….n (10).

Then Si is a SPR of derivation type) over Si-1, for all i=1,2,…n, if, and only if, diodj=djodi, for all i, j=1,2,….n.

Proof: Assume first that the elements of D commute to each other. Obviously S1=R[x1; d1] is a SPR over R. We apply induction on n. For this, assume that Si is a skew polynomial ring over Si-1 for each i . By Lemma 3.1 dn is extended to a derivation of S1 by dn(x1)=0. But, by our inductive hypothesis, S2=S1[x2, d2] is a skew polynomial ring over S1. Therefore, by Lemma 3.1 dn, being a derivation of S1, can be extended to a derivation of S2 by dn(x2)=0 and so on. Keep going in the same way one finds after a finite number of steps that dn can be extended to a derivation of Sn-1 by dn(xi)=0, i=1,2,…,n-1.

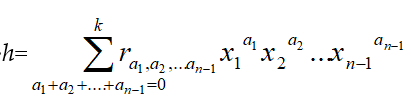

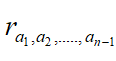

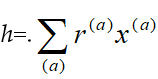

Let now

Thus Sn=Sn-1[xn; dn] is a SPR over Sn-1.

Conversely, assume that Si is a SPR over Si-1, for all i=1,2,.,n. Then, since Sn=Sn-1[xn,dn] is a SPR over Sn-1 and xi belongs to Sn-1 for each i, 1 <n, we have that xnxi=xixn+dn(xi). Therefore by the second of rules (10), we get that dn(xi)=0.

Further, given r in R we have that xir=rxi+di(r). Therefore dn(xir)=dn(rxi)+dn[di(r)], or xidn(r)=dn(r)xi+dn[di(r)]. But xidn(r)= dn(r) xi+di[dn(r)] and the last two equalities imply that dnodi=diodn. In the same way and for each j=1,2,…,n, one can show that djodi=diodj, for all i, 1 i<j and this completes the proof.

Theorem 2.2 shows that, if the derivations of D commute to each other, then Sn=R[x; D], with addition defined in the usual way and multiplication by the rules (10) and the distributive law, is an ISPR of derivation type over R.

In a more general context, one can define an ISPR over R of the form R[x; H, D] with H a finite set of monomorphisms of R and D a finite set of skew derivations of R defined with respect to the monomorphisms of H, provided that all these maps commute pairwise to each other ([11], Theorem 2.4).

The following example illustrates Theorem 3.2:

Example 3.3: Let R=T[y1,y2,….,yn] be a polynomial ring over a ring T.

Set D={ , ,…., }. Since the elements of R are polynomials with coefficients in T, their partial derivatives are continuous functions. Therefore, by the Young’s classical theorem of differential calculus, the derivations of D commute to each other.

Consider the set Sn of all polynomials in n variables, say x1, x2,…., xn, with coefficients in R and define in Sn addition in the usual way and multiplication by the rules

hxi=xih+ for all h in R and xixj=xjxi, i, j=1,…,n.

Then, by Theorem 3.2, Sn=R[x; D] is an ISPR of derivation type over the polynomial ring R. It is easy to check that yixi=xiyi+1, while yixj=xjyi for i , i, j=1,2,…,n.

Remarks 3.4:

- In order to be in the ISPR of Theorem 3.2 it is necessary to have

di o d = d o d I, for all i, j=1,2,…,n. In fact, given r in R, we have

r = x ] = (xir)xj + xidj(r) = rxixj + di(r)xj + dj(r)xi + (diodj)(r). In the same way one finds that x r = rxjxi + dj(r)xi + di(r)xj + (djodi)(r). The result follows by equating the right hand sides of those two equations.

- ii) If there exist, however, x’s in Sn not commuting to each other, this does not mean that the same must happen with the derivations of D. An example illustrating this situation is the n-th Weyl algebra An(T) over a ring T, n (see example 2.5, iii). In fact, the elements of An(T) are polynomials over T and therefore, as we have shown above, the derivations of D commute to each other, whereas the x’s don’t commute (Example 2.3).

iii) SPRs in finitely many variables over a ring R, not necessarily commuting to each other, with respect to a finite set of derivations of R have been firstly introduced by Kishimoto [12]. In those SPRs, which need not be ISPRs over R, multiplication is defined by the first (only) of rules (10) and the distributive law.

We shall close this article by mentioning some important properties of the special class of ISPRs defined in this Section, which have been proved in earlier works of the present author. For this, it is necessary to recall the following definitions:

Definition 3.5: A derivation d of a ring R is called an inner derivation induced by an element s of R, if d(r)=sr-rs, for all r in R. A derivation of R which is not inner is called an outer derivation.

Note also that an outer derivation of R is possible to be extendable to an inner derivation of a SPR of derivation type over R. For example, d= is an outer derivation of the polynomial ring R=T[x1] over a ring T, because x1 is a central element of R and d(x1)=1 . But d is extended to an inner derivation of A1(T)=R[x2,d] induced by x2, because, by the definition of multiplication in A1(T), we have that x2f=fx2+d(f), or d(f)=x2f-fx2, for all f in R.

Definition 3.6: Let R be a ring and let D be a set of derivations of R. Then an ideal I of R is called a D-ideal, if d(I) I for all derivations d in D , and R is called a D-simple ring if it has no non trivial D-ideals.

Every D-simple ring R contains the field F= C(R) ker d], where C(R) denotes the center of R, therefore R is either of characteristic zero or of a prime number p. Non commutative D-simple rings exist in abundance, e.g. every simple ring R is D-simple for any set D of derivations of R. Characteristic examples of commutative D-simple rings can be found in [13].

Definition 3.7: Let D be a set of derivations of a ring R. Then, a D- ideal I of R is called D-prime ideal, if, given any two D-ideals A, B of R such that AB I, is either A , or B . Also, I is called D-semiprime ideal, if for all D-ideals A of R and any positive integer k such that Ak , is A .

Remarks 3.8:

(i) Let R be a ring of characteristic zero and let D={d1,……, dn} be a finite set of derivations of R commuting to each other. Set S0=R and assume that R is a D-simple ring and that di is an outer derivation of Si-1, for i=1,2,…,n. Then Sn=R[x; D] is a simple ring ([14], Theorem 3.4).

Conversely, if Sn=R[x; D] is a simple ring, then no element of D is an inner derivation of R induced by an element of , where Kerd is the kernel of d, and R is a D-simple ring ([14], Theorem 3.3).

Analogous results, with a little bit more complicated statement, hold if R is of prime characteristic ([15], Theorems 2.3 and 2.4).

As an immediate consequence of the previous results, if R is a commutative ring, then Sn=R[x; D] is a simple ring, if, and only if, R is a D-simple ring.

(ii) Let R, D and Sn be as in the previous remark. Then, if P is a prime ideal of Sn, P R is a D-prime ideal of R ([16], Theorem 2.2]. Conversely, if I is a D-prime ideal of R, then ISn is a prime ideal of Sn ([16], Theorem 2.6). Analogous relations hold among the semiprime ideals of Sn and the D-semiprime ideals of R [17].

4. Conclusion

The study of SPRs used to be of great theoretical importance for the abstract Algebra some decades ago, but the recent renewal of interest about them is due to the fact that they have found practical applications too. In this work a special class of ISPRs over a ring R with respect to a finite set D of pairwise commuting derivations of R was constructed. The simplicity of those ISPRs is connected to the D-simplicity of R and their prime ideals correspond to D-prime ideals of R. The attempt to obtain further properties of those ISPRs with respect to corresponding properties of R could be a good hint for future research on the subject.

References

- Zadeh, L.A., Fuzzy Sets, Information and Control, 1965, 8(3), 338–353.

- Mandelbrot, Benoit, B., The Fractal Geometry of Nature, W. H. Freeman and Company, 1983

- Peitgen, H.-O., Jurgens, H. & Saupe, D., Chaos and Fractals: New Frontiers of Science, Springer-Verlag, 1992.

- Voskoglou, M.Gr., Studying the Winger’s “Enigma” about the Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences, American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 2017, 5(3), 95-100.

- Athanassopoulos, E. and Voskoglou, M.Gr., A Philosophical Treatise on the Connection of Scientific Thinking with Fuzzy Logic, Mathematics, 2020, 8, 875.

- Ore, O., Theory of noncommutative polynomials, Ann. of Math., 1933, 34, 480-503.

- Majid, S., What is a Quantum group? Notices of the American Math. Soc., 2006, 53, 30-31.

- Jategaonkar, V., Skew Polynomial Rings over Semisimple Rings, Journal of Algebra, 1971, 19, 315-328.

- Lopez-Permouth, S., Matrix Representations of Skew Polynomial Ring with Semisimple Coefficient Rings, Contemporary Mathematics, 2009, 480, 289-295.

- Goodearl, K.R. & Warfield, Jr., An Introduction to Noncommutative Noetherian Rings, Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004.

- Voskoglou, M. Gr., Extending derivations and endomorphisms to skew polynomial rings, Inst. Math. (Beograd), 1986, 39 (53), 79-82.

- Kishimoto, K., On abelian extensions of simple rings, Fuc. Sci., 1967, Hokkaido Univ., 20, 53-78.

- Voskoglou, M. Gr., Differential simplicity and dimension of a commutative ring, Mat. Univ. Parma, 2001, (6), 4, 111-119.

- Voskoglou, M. Gr., Simple skew polynomial rings, Inst. Math. (Beograd), 1985, 37 (51), 37-41.

- Voskoglou, M. Gr., A note on skew polynomial rings, Inst. Math.(Beograd), 1994, 55 (69), 23-28.

- Voskoglou, M. Gr., Prime ideals of skew polynomial rings, Mat. Univ. Parma, 1989, (4),15, 17-25.

- Voskoglou, M. Gr., Semiprime ideals of skew polynomial rings, Inst. Math. (Beograd), 1990, 47 (61), 33-38.