Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Chloe Sun and Version 1 by Helen O'Sullivan.

Branding refers to the distinctiveness of an organization that differentiates it from its competitors and builds loyalty with customers. Brand trust is the confidence consumers have in a company to deliver consistently against their expectations of the brand. Brand equity is the commercial value that a brand has and is linked to consumer perception and loyalty. Culture refers to the expected behaviors of a defined group of people, e.g., customers. Brand activism is when an organization takes a visible ideological stance associated with a specific issue or social concern. Socio-political branding refers to the practice of using brand activism specifically to connect with certain key stakeholder groups.

- brand

- loyalty

- activism

- consumer

- trust

- socio

- political

- value

- culture

In the contemporary branding landscape, the boundaries between commerce, culture and politics have become increasingly blurred over time [1,2][1][2]. In today’s world, brands are no longer viewed simply as being economic entities that sell goods and services, and instead they are increasingly expected to engage meaningfully with the socio-political issues that shape public discourse [3]. This development has given rise to what is often referred to as brand activism, which is a strategic and ideologically visible stance that an organization may choose to adopt in response to pressing social, environmental and political concerns [4,5][4][5].

Brand activism is embedded in a company’s identity, and socio-political branding is then communicated through its products, advertising and public engagements [6]. Often, it is not merely about ‘doing good’ and in fact it is more about being seen to ‘take a stand’ [7]. Brands now often publicly align themselves with movements such as Black Lives Matter, Fridays for Future, LGBTQ+ rights, mental health awareness and anti-racism, all of which signal a shift in how the brand value for these organizations is constructed and maintained in contemporary markets [8,9][8][9].

This ongoing shift in position has important implications for the way brand equity is conceptualized. Classic models of brand equity, such as those developed by Aaker [10,11][10][11] and Keller [12], focus on key elements including awareness, loyalty and perceived quality [13]. However, in today’s value-driven marketplace, these elements are also increasingly influenced by how a brand’s political and ethical positioning is aligned to their consumers’ own values [14].

Consumers now evaluate brands not only on functional attributes, or esthetic appeal, but also on perceived integrity, authenticity and alignment with their personal beliefs [15]. These dimensions introduce emotional and ideological risk into brand–consumer relationships, especially when there is a perceived gap between what a brand claims and what is practiced [16]. This especially applies to Generation Z (Gen Z), who are defined broadly as those born between 1997 and 2012 [17], and who are the first cohort to grow up fully immersed in digital technologies and global information flow [18]. As such, they are not only technologically savvy, but also acutely socially aware, politically engaged and value-driven [19,20,21][19][20][21]. As a result, Gen Z are much quicker to ‘call out’ brands that appear to be inauthentic [22,23][22][23].

Foundational branding literature emphasizes that brand identity is shaped not only by visual assets or positioning, but also by the deeper meanings that brands cultivate with their audiences [11,24][11][24]. Increasingly, however, this identity is not defined solely by organizations but instead is being co-created through ongoing interaction between brands, consumers and cultural publics. As O’Sullivan et al. [25] highlighted, this co-creative process is especially salient in socio-political contexts, where branding intersects with ethical expectations, and the consumer voice plays a central role in evaluating authenticity.

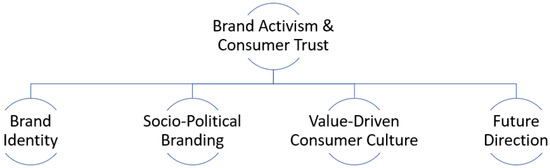

Building on these concepts, this paper seeks to synthesize and evaluate academic research at the intersection of branding, socio-political engagement and consumer behavior, with a specific emphasis on the role of authenticity, emotional connection and generational change. To achieve this, we have applied an interpretive classification schema as the analytical framework for the study (Figure 1) in which the categories of brand identity, socio-political branding, value-driven consumer culture and the future direction have each been considered in turn. For this study, we have included older publications considered to be key to the development of this discipline area, and we have also included newer publications that articulate current thinking regarding many of these evolving issues.

Figure 1. The interpretive classification schema used for this study.

Ultimately, this paper concludes that socio-political branding is increasingly necessary for organizations operating in ethically aware markets. However, the decision to ‘take a stand’ brings with it new strategic challenges. In the age of digital transparency and consumer activism, brand trust must be earned through consistency, accountability and genuine social contribution, not just by delivering compelling campaigns and catchy slogans.

References

- Solomon, M.; Englis, B. Reality engineering: Blurring the boundaries between commercial signification and popular culture. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 1994, 16, 1–17.

- Swaminathan, V.; Sorescu, A.; Steenkamp, J.; O’Guinn, T.; Schmitt, B. Branding in a hyperconnected world: Refocusing theories and rethinking boundaries. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 24–46.

- Fournier, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Marrinan, P. Turning socio-political risk to your brand’s advantage. NIM Mark. Intell. Rev. 2021, 13, 18–25.

- Sarkar, C.; Kotler, P. Brand Activism: From Purpose to Action; Penguin Random House: London, UK, 2021.

- Vredenburg, J.; Kapitan, S.; Spry, A.; Kemper, J. Brands taking a stand: Authentic brand activism or woke washing? J. Public Policy Mark. 2020, 39, 444–460.

- Khojastehpour, M.; Johns, R. The effect of environmental CSR issues on corporate/brand reputation and corporate profitability. Euro. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 330–339.

- Robinson, S.; Wood, S. A “good” new brand—What happens when new brands try to stand out through corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 231–241.

- Shirdastian, H.; Laroche, M.; Richard, M. Using big data analytics to study brand authenticity sentiments: The case of Starbucks on Twitter. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 291–307.

- Ren, Y.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Antecedents and consequences of brand equity: Evidence from Starbucks coffee brand. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103351.

- Aaker, D. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Aaker, D. Building Strong Brands; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996.

- Keller, K. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22.

- Polat, A.; Çetinsöz, B. The mediating role of brand love in the relationship between consumer-based brand equity and brand loyalty: A research on Starbucks. J. Tour. Serv. 2021, 12, 150–167.

- Walters, P. Are Generation Z Ethical Consumers? In Generation Z Marketing and Management in Tourism and Hospitality: The Future of the Industry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 303–325.

- Bhagwat, Y.; Warren, N.; Beck, J.; Watson, G., IV. Corporate sociopolitical activism and firm value. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 1–21.

- Greyser, S. Corporate brand reputation and brand crisis management. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 590–602.

- Wadud, I.; Liang, Y.; Polkinghorne, M. Digital Transformation in the UK Retail Sector. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 142–154.

- Witt, G.; Baird, D. The Gen Z Frequency: How Brands Tune in and Build Credibility; Kogan Page Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Francis, T.; Hoefel, F. True Gen’: Generation Z and Its Implications for Companies; McKinsey & Company: São Paulo, Brazil, 2018.

- Turner, A. Generation Z: Technology and social interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 2015, 71, 103–113.

- Accenture. To Affinity and Beyond. From Me to We, the Rise of the Purpose-Led Brand; Accenture: Dublin, Ireland, 2018; Available online: https://www.accenture.com/content/dam/accenture/final/a-com-migration/custom/_acnmedia/thought-leadership-assets/pdf/Accenture-CompetitiveAgility-GCPR-POV.pdf#zoom=40 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Saldanha, N.; Mulye, R.; Rahman, K. Cancel culture and the consumer: A strategic marketing perspective. J. Strat. Mark. 2023, 31, 1071–1086.

- Demsar, V.; Ferraro, C.; Nguyen, J.; Sands, S. Calling for cancellation: Understanding how markets are shaped to realign with prevailing societal values. J. Macromarketing 2023, 43, 322–350.

- Kapferer, J. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2008.

- O’Sullivan, H.; Polkinghorne, M.; Chapleo, C.; Cownie, F. Contemporary branding strategies for higher education. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1292–1311.

More