Epigenetic clocks, based on DNA methylation patterns, provide a robust measure of biological age, often correlating with health outcomes and lifestyle factors. This study introduces AlphaAge, a novel saliva-based epigenetic clock trained exclusively on male samples, utilizing linear regression to model age-related hypermethylation across selected CpG sites. Using a cohort of 1,038 male individuals, we demonstrate strong predictive accuracy with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.83 between chronological age and predicted biological age, and an R² of 0.69 to include health variability in the regression model. Biological variability is assessed through residual analysis and site-specific correlations, revealing key CpG sites in genes associated with aging processes. In a secondary analysis, we evaluate AlphaAge in a cohort of 118 male athletes engaged in hybrid athletic events (e.g., CrossFit, HYROX). Athletes exhibit a statistically significant deceleration in biological aging (mean chronological age minus predicted age = 1.15 years, SD = 5.37, t-test p = 0.015), suggesting potential links between athletic training and enhanced biological health or athletic potential. These findings underscore the utility of saliva-based clocks for non-invasive aging assessments and highlight epigenetic correlates of physical fitness.

- epigenetics

- male health

- age

- crossfit

- hyrox

- fitness

- wellness

- DNA

1. Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Epigenetic modifications, particularly DNA methylation at CpG sites, undergo systematic changes with chronological age, forming the basis for epigenetic clocks—predictive models that estimate biological age. These clocks have shown strong correlations with morbidity, mortality, and lifestyle factors, often outperforming chronological age in predicting healthspan. Traditional clocks, such as those by Horvath and Hannum, rely on blood-derived data and mixed-sex cohorts, potentially overlooking sex-specific patterns and tissue variability. Saliva offers a non-invasive alternative, rich in epithelial and immune cells, with emerging evidence supporting its use in epigenetic aging studies [1],[2].

This paper presents AlphaAge, a linear regression-based epigenetic clock trained on saliva samples from males only, focusing on hypermethylation trends with advancing age. The primary emphasis is on statistical validation, including model fit, biological variability, and site-specific contributions. Secondarily, we investigate the clock's application to a cohort of advanced male athletes in hybrid sports, hypothesizing that rigorous physical training may modulate biological aging, potentially correlating with superior health and athletic potential. By restricting to males, AlphaAge addresses sex biases in methylation dynamics, enhancing precision for male-specific applications.

2. Methods

METHOD

2.1. Data Sources

Data Sources

The training dataset comprised saliva-derived DNA methylation profiles from 1,038 male individuals with chronological ages ranging from approximately 13 to 89 years (mean ≈ 50 years, SD ≈ 20 years). Methylation beta values were measured at 850,000 CpG sites using a Illumina methylation array (EPIC) and data is purged from the Muhdo Health Ltd. Data set, from this 285 CpG sites were chosen linked to multiple genes (Table 12) with the strongest correlation in males and age, with many kept in for biological variability. CpG site annotations, including genomic location and associated genes, were obtained from standard Illumina annotations.

A separate validation cohort included 118 male athletes aged approximately 29–37 years. All athletes were actively engaged in community-based fitness programs characterized by high-intensity, mixed-modality training, including CrossFit, HYROX, and related functional fitness disciplines. Ages in this cohort were rounded to preserve participant anonymity; this rounding introduces non-differential measurement noise expected to bias estimates toward the null.

2.2. Statistical Modeling

Statistical Modeling

AlphaAge was constructed using ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression, predicting chronological age from the mean methylation value across the selected CpG sites. Mean methylation was used as a proxy for the aggregated age-associated hypermethylation signal rather than a weighted, site-specific clock.

Model performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²), root mean square error (RMSE), and Pearson correlation between observed and predicted ages. Biological variability was quantified via residual analysis. Site-specific Pearson correlations between methylation beta values and chronological age were computed independently to identify CpG sites most strongly associated with aging; these correlations were not used to weight the regression model.

For the athlete cohort, predicted biological ages were generated using the trained AlphaAge model. Age deceleration was defined as chronological age minus predicted biological age, with positive values indicating slower biological aging. A one-sample t-test was used to assess whether mean age deceleration differed from zero. Effect sizes were reported using Cohen’s d. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

Results

AlphaAge demonstrated strong predictive accuracy across the training cohort. Mean methylation exhibited a robust correlation with chronological age (Pearson r = 0.83, p < 3.6 × 10⁻²⁶³). The linear regression model explained 69% of the variance in age (R² = 0.69), with a residual standard error of approximately 11.5 years, reflecting substantial inter-individual biological variability beyond chronological age, key for a health variable clock.

Analysis of site-specific correlations identified multiple CpG sites with strong age associations. The highest-ranked sites included cg16867657 located in the promoter region of ELOVL2, a well-established epigenetic aging marker, as well as sites mapping to otherKLF14, wellFHL2, kanownd markersPDE4C. These CpGs were predominantly located in promoters, gene bodies, and CpG islands, consistent with known patterns of age-related hypermethylation.

Table 1. Top 10 CpG Sites by Correlation with Chronological Age

SYNGR3 |

|

ACTN2 |

CPM |

GRIA2 |

OCA2 |

PEX5L |

SYT7 |

|

ADRB1 |

CTNNA2 |

GRIN2C |

OPRM1 |

PHACTR1 |

TAC1 |

|

ALDH1A2 |

CYP1B1 |

GRM2 |

OTUD7A |

PPM1E |

TBR1 |

|

ANKRD34B |

DCHS2 |

HAGLR |

PBX1 |

PRDM6 |

TCF21 |

|

ANKRD34C |

DFNB31 |

HOXD1 |

PCDH8 |

PRLHR |

TLX3 |

|

ANKRD43 |

DHX40 |

HOXC4 |

PCDHA7 |

PRMT8 |

TMEM181 |

|

AP3B2 |

DLEU7 |

HOXC5 |

PCDHA12 |

PRRT1 |

TRIM59 |

|

ATP4A |

DPP6 |

IL4I1 |

PCDHA6 |

PTPRN |

TSPYL5 |

|

ATP8A2 |

DRD5 |

IRS2 |

PCDHAC1 |

PTPRN2 |

TSSK6 |

|

AVPR1A |

DTNA |

IRX1 |

PCDHA10 |

RANBP17 |

VGF |

|

B3GNT9 |

EBF3 |

KCNC2 |

PCDHA4 |

RASL11B |

VIM |

|

BARHL2 |

ELAVL4 |

KCNK12 |

PCDHA11 |

RGS22 |

XKR4 |

|

BMP4 |

ELOVL2 |

KCNK3 |

PCDHA8 |

RHBDD1 |

YPEL1 |

|

BMP8A |

ELTD1 |

KCNS1 |

PCDHA1 |

RPA2 |

ZAR1 |

|

BOK |

EPHA10 |

KIAA1383 |

PCDHA2 |

RYR2 |

ZDHHC22 |

|

BRUNOL6 |

EPHX3 |

KIAA1409 |

PCDHA9 |

SCG3 |

ZIC1 |

|

C10orf82 |

ERRFI1 |

KLF14 |

PCDHA13 |

SCGN |

ZIC5 |

|

C17orf104 |

FAM123C |

LEP |

PCDHA5 |

SFRS13B |

ZIK1 |

|

C19orf51 |

FAM19A1 |

LHFPL4 |

PCDHA3 |

SHANK1 |

ZNF177 |

|

C1orf59 |

FAM19A4 |

LHX8 |

PCDHB15 |

SLC12A5 |

ZNF274 |

|

CACNA1B |

FBLL1 |

MIR9-3 |

PCDHGA4 |

SLC6A4 |

ZNF382 |

|

CACNA1G |

FHL2 |

MTMR7 |

PCDHGA2 |

SLC7A10 |

ZNF529 |

|

CACNG2 |

FOXD3 |

NBLA00301 |

PCDHGB2 |

SLITRK3 |

ZNF518B |

|

CACNG8 |

FOXE3 |

HAND2 |

PCDHGA1 |

SOBP |

ZNF577 |

|

CALB1 |

FOXG1 |

NCRNA00028 |

PCDHGB1 |

SOX1 |

ZNF578 |

|

CCDC85C |

FZD9 |

REM1 |

PCDHGA3 |

SOX17 |

ZNF75A |

|

CCNI2 |

GATA4 |

NEFM |

PCDHGA6 |

SOX30 |

ZPBP2 |

|

CDH23 |

GCK |

NEURL1B |

PCDHGA5 |

SPAG6 |

ZSCAN1 |

|

CELF6 |

GCM2 |

NKX2-6 |

PCDHGA7 |

SRRM4 |

ZYG11A |

|

CHGA |

GLRA1 |

NOVA2 |

PCDHGB4 |

SST |

|

|

CILP2 |

GPR158-AS1 |

NPTX2 |

PCDHGB3 |

STAG3 |

|

|

CNGA3 |

GPR62 |

NPY |

PDE4C |

GPC2 |

|

|

CNTN4 |

GPR78 |

NRIP3 |

PDE4D |

STXBP5L |

|

|

CNTNAP5 |

GREM1 |

NXPH1 |

PENK |

SYNGR3 |

|

Rank |

CpG Site |

Gene/Location |

Correlation (r) |

|

1 |

cg12841266 |

LHFPL4 (Body) |

0.75 |

|

2 |

cg16867657 |

ELOVL2 (Promoter) |

0.74 |

|

3 |

cg24866418 |

TAC1 (TSS200) |

0.74 |

|

4 |

cg13206721 |

Unknown (Island) |

0.73 |

|

5 |

cg13327545 |

DHX40 (TSS200) |

0.71 |

|

6 |

cg00059225 |

FHL2 (TSS200) |

0.71 |

|

7 |

cg07547549 |

SST (Body) |

0.70 |

|

8 |

cg11084334 |

PDE4C (5'UTR) |

0.69 |

|

9 |

cg21572722 |

HAND2 (TSS1500) |

0.69 |

|

10 |

cg04875128 |

KLF14 (TSS1500) |

0.69 |

Table 12. Whole Gene List.

Whole Gene List

|

ACTN2 |

CPM |

GRIA2 |

OCA2 |

PEX5L |

SYT7 |

|

ADRB1 |

CTNNA2 |

GRIN2C |

OPRM1 |

PHACTR1 |

TAC1 |

|

ALDH1A2 |

CYP1B1 |

GRM2 |

OTUD7A |

PPM1E |

TBR1 |

|

ANKRD34B |

DCHS2 |

HAGLR |

PBX1 |

PRDM6 |

TCF21 |

|

ANKRD34C |

DFNB31 |

HOXD1 |

PCDH8 |

PRLHR |

TLX3 |

|

ANKRD43 |

DHX40 |

HOXC4 |

PCDHA7 |

PRMT8 |

TMEM181 |

|

AP3B2 |

DLEU7 |

HOXC5 |

PCDHA12 |

PRRT1 |

TRIM59 |

|

ATP4A |

DPP6 |

IL4I1 |

PCDHA6 |

PTPRN |

TSPYL5 |

|

ATP8A2 |

DRD5 |

IRS2 |

PCDHAC1 |

PTPRN2 |

TSSK6 |

|

AVPR1A |

DTNA |

IRX1 |

PCDHA10 |

RANBP17 |

VGF |

|

B3GNT9 |

EBF3 |

KCNC2 |

PCDHA4 |

RASL11B |

VIM |

|

BARHL2 |

ELAVL4 |

KCNK12 |

PCDHA11 |

RGS22 |

XKR4 |

|

BMP4 |

ELOVL2 |

KCNK3 |

PCDHA8 |

RHBDD1 |

YPEL1 |

|

BMP8A |

ELTD1 |

KCNS1 |

PCDHA1 |

RPA2 |

ZAR1 |

|

BOK |

EPHA10 |

KIAA1383 |

PCDHA2 |

RYR2 |

ZDHHC22 |

|

BRUNOL6 |

EPHX3 |

KIAA1409 |

PCDHA9 |

SCG3 |

ZIC1 |

|

C10orf82 |

ERRFI1 |

KLF14 |

PCDHA13 |

SCGN |

ZIC5 |

|

C17orf104 |

FAM123C |

LEP |

PCDHA5 |

SFRS13B |

ZIK1 |

|

C19orf51 |

FAM19A1 |

LHFPL4 |

PCDHA3 |

SHANK1 |

ZNF177 |

|

C1orf59 |

FAM19A4 |

LHX8 |

PCDHB15 |

SLC12A5 |

ZNF274 |

|

CACNA1B |

FBLL1 |

MIR9-3 |

PCDHGA4 |

SLC6A4 |

ZNF382 |

|

CACNA1G |

FHL2 |

MTMR7 |

PCDHGA2 |

SLC7A10 |

ZNF529 |

|

CACNG2 |

FOXD3 |

NBLA00301 |

PCDHGB2 |

SLITRK3 |

ZNF518B |

|

CACNG8 |

FOXE3 |

HAND2 |

PCDHGA1 |

SOBP |

ZNF577 |

|

CALB1 |

FOXG1 |

NCRNA00028 |

PCDHGB1 |

SOX1 |

ZNF578 |

|

CCDC85C |

FZD9 |

REM1 |

PCDHGA3 |

SOX17 |

ZNF75A |

|

CCNI2 |

GATA4 |

NEFM |

PCDHGA6 |

SOX30 |

ZPBP2 |

|

CDH23 |

GCK |

NEURL1B |

PCDHGA5 |

SPAG6 |

ZSCAN1 |

|

CELF6 |

GCM2 |

NKX2-6 |

PCDHGA7 |

SRRM4 |

ZYG11A |

|

CHGA |

GLRA1 |

NOVA2 |

PCDHGB4 |

SST |

|

|

CILP2 |

GPR158-AS1 |

NPTX2 |

PCDHGB3 |

STAG3 |

|

|

CNGA3 |

GPR62 |

NPY |

PDE4C |

GPC2 |

|

|

CNTN4 |

GPR78 |

NRIP3 |

PDE4D |

STXBP5L |

|

|

CNTNAP5 |

GREM1 |

NXPH1 |

PENK |

3.1.

Application to Community-Based Fitness Athletes

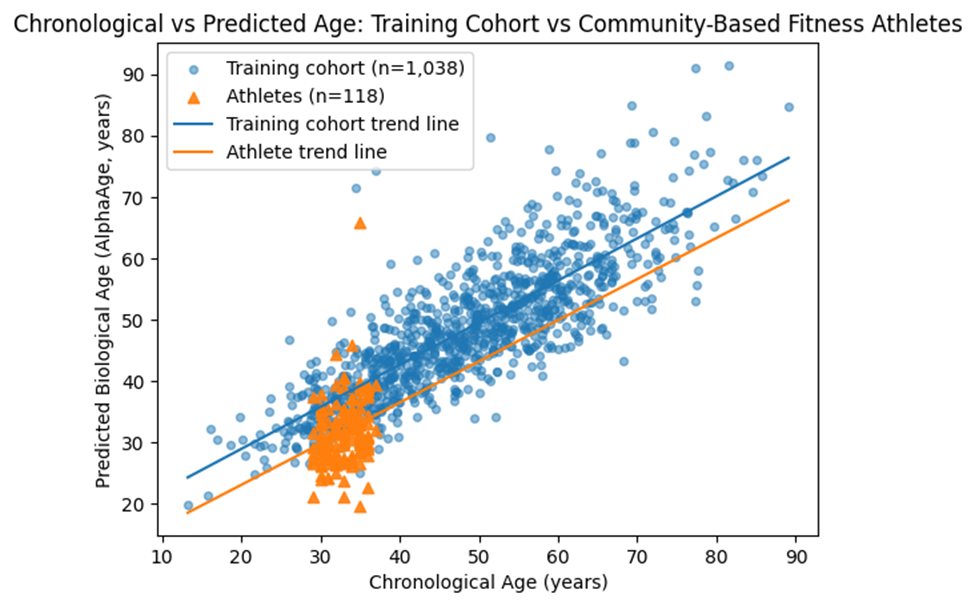

Within the athlete cohort, mean chronological age was 33.2 years (SD = 2.3), while mean predicted biological age was 32.05 years. This corresponded to a mean age deceleration of 1.15 years (SD = 5.37). A one-sample t-test indicated that this deceleration was statistically significant (t(117) = 2.47, p = 0.015), with a small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.21).

Residual variability in the athlete cohort was comparable to that observed in the training dataset, indicating stable model performance. Subgroup analyses across narrow age bins showed no significant differences in age deceleration, suggesting a relatively uniform effect across the sampled age range.

Figure 1. Trend graph showing a clear linear trend of lowered age in the community-based fitness community.

4. Discussion

Discussion

This study presents AlphaAge, a male-specific, saliva-derived epigenetic clock designed to capture age-associated DNA methylation changes using a parsimonious linear modeling approach. The results demonstrate that even a simplified aggregation of age-correlated CpG sites can achieve strong predictive performance, with a correlation of 0.83 between chronological and predicted age and an R² of 0.69. These values are comparable to early-generation epigenetic clocks and support the premise that biologically meaningful aging signals can be recovered without reliance on highly complex, heavily weighted models.

4.1. Biological Interpretation and Model Design

A defining feature of AlphaAge is its reliance on mean methylation across a curated set of age-associated CpG sites rather than a site-weighted regression framework. While contemporary clocks often employ elastic net or machine-learning approaches to optimize predictive accuracy, such methods may obscure biological interpretability and amplify overfitting to specific tissues or populations. In contrast, the AlphaAge approach emphasizes robustness and biological plausibility by modeling the dominant hypermethylation signal observed with advancing age.

The identification of canonical aging-associated CpG sites—most notably within the ELOVL2 promoter—provides strong biological validation of the clock. ELOVL2 has been repeatedly identified as one of the most reproducible epigenetic markers of aging across tissues and populations, and its prominence in this saliva-based, male-only model reinforces the conserved nature of core aging pathways. Additional sites mapping to genes such as KLF14, FHL2, PDE4C, and HAND2 further implicate regulatory networks involved in metabolic control, transcriptional regulation, and cellular signaling, all of which are processes known to deteriorate with age [2][3][4].

The residual variance observed in AlphaAge predictions is substantial, with a residual standard error of approximately 11.5 years. Importantly, this variance should not be interpreted as model weakness. Rather, it reflects meaningful inter-individual biological heterogeneity that is not explained by chronological age alone. Such heterogeneity likely arises from a combination of genetic background, environmental exposures, lifestyle behaviors, psychosocial stress, and health status [5][6] From an applied perspective, this residual variance represents the very signal of interest when biological age is used as a proxy for health or physiological resilience.

4.2. Sex-Specific and Tissue-Specific Considerations

By restricting training to male samples, AlphaAge directly addresses a known limitation of many existing epigenetic clocks: the assumption that age-associated methylation dynamics are equivalent across sexes. Sex differences in hormonal regulation, immune function, and gene expression are well documented and are increasingly recognized as influencing epigenetic aging trajectories. A male-specific model therefore improves precision for applications in male populations, particularly in sports, occupational health, and military or tactical settings where sex-specific physiological demands are relevant.

The use of saliva as the biological substrate further enhances the translational utility of AlphaAge. Saliva sampling is non-invasive, scalable, and well suited for repeated or community-based testing. Although saliva contains a heterogeneous mixture of epithelial and immune cells, prior research indicates that age-associated methylation signals remain robust across tissues. The strong performance of AlphaAge supports the feasibility of saliva as a practical alternative to blood for epigenetic aging assessment, particularly outside of clinical laboratory environments matching previous saliva studies [2].

4.3. Biological Age Deceleration in Community-Based Fitness Athletes

Application of AlphaAge to a cohort of male community-based fitness athletes revealed a modest but statistically significant deceleration of biological age relative to chronological age. On average, athletes exhibited a biological age approximately 1.15 years younger than expected, with an effect size in the small range. While the magnitude of this effect is modest, it is notable given the relatively narrow age range of the cohort and the cross-sectional nature of the analysis.

Hybrid training modalities such as CrossFit and HYROX combine high-intensity aerobic exercise, resistance training, and metabolic conditioning. These forms of training are associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial function, inflammatory regulation, and cardiovascular health—all pathways that have been implicated in epigenetic aging [2]. It is therefore biologically plausible that sustained engagement in such training could influence DNA methylation patterns in a direction consistent with slower biological aging.

In addition to physiological mechanisms, the social and psychological dimensions of community-based fitness may also contribute. Structured group training environments are associated with enhanced social connectedness, motivation, and mental well-being, factors that may indirectly influence biological aging through stress reduction and improved behavioral adherence. While speculative, these psychosocial factors warrant consideration in future studies examining lifestyle influences on epigenetic aging.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the athlete analysis is cross-sectional and cannot establish causality. It remains unclear whether participation in high-intensity functional fitness slows biological aging, or whether individuals with inherently lower biological age are more likely to engage in or sustain such training. Longitudinal studies and intervention-based designs will be required to disentangle these effects.

Second, AlphaAge prioritizes interpretability and robustness over maximal predictive accuracy. The use of mean methylation rather than site-specific weighting may limit sensitivity to subtle age-related changes. However, this design choice enhances generalizability and reduces susceptibility to overfitting, making the clock well suited for applied and population-level use.

Finally, although the male-only design is a strength for sex-specific applications, it limits generalizability to females. Future work should explore whether analogous female-specific saliva-based clocks exhibit similar performance characteristics or aging dynamics.

5. Conclusion

Conclusion

AlphaAge provides a statistically robust, biologically plausible, and non-invasive approach to estimating biological age in males using saliva-derived DNA methylation data. Its application to community-based fitness athletes suggests a potential association between sustained functional fitness training and slower biological aging. AlphaAge represents a practical tool for research and applied settings where male-specific, saliva-based aging assessment is desirable.

Contributions

- Obiekwe – Proofing and methods

- Khan – Methods

- Collins – Data analysis

Funding information

Data made available via. Muhdo health ltd.

References

- Ake T. Lu; Alexandra M. Binder; Joshua Zhang; Qi Yan; Alex P. Reiner; Simon R. Cox; Janie Corley; Sarah E. Harris; Pei-Lun Kuo; Ann Z. Moore; Stefania Bandinelli; James D. Stewart; Cuicui Wang; Elissa J. Hamlat; Elissa S. Epel; Joel D. Schwartz; Eric A. Whitsel; Adolfo Correa; Luigi Ferrucci; Riccardo E. Marioni; Steve Horvath; DNA methylation GrimAge version 2. Aging. 2022, 14, 9484-9549.

- Christopher Collins; James Brown; Henry C. Chung; A Cost-Effective Saliva-Based Human Epigenetic Clock Using 10 CpG Sites Identified with the Illumina EPIC 850k Array. DNA. 2025, 5, 28.

- Daniel L. Chao; Dorota Skowronska-Krawczyk; ELOVL2: Not just a biomarker of aging. Transl. Med. Aging. 2020, 4, 78-80.

- Noha M. El-Shishtawy; Fatma M. El Marzouky; Hanan A. El-Hagrasy; DNA methylation of ELOVL2 gene as an epigenetic marker of age among Egyptian population. Egypt. J. Med Hum. Genet.. 2024, 25, 1-8.

- Te-Min Ke; Artitaya Lophatananon; Kenneth R. Muir; Exploring the Relationships between Lifestyle Patterns and Epigenetic Biological Age Measures in Men. Biomed.. 2024, 12, 1985.

- Nuria Garatachea; Helios Pareja-Galeano; Fabian Sanchis-Gomar; Alejandro Santos-Lozano; Carmen Fiuza-Luces; María Morán; Enzo Emanuele; Michael J. Joyner; Alejandro Lucia; Exercise Attenuates the Major Hallmarks of Aging. Rejuvenation Res.. 2015, 18, 57-89.