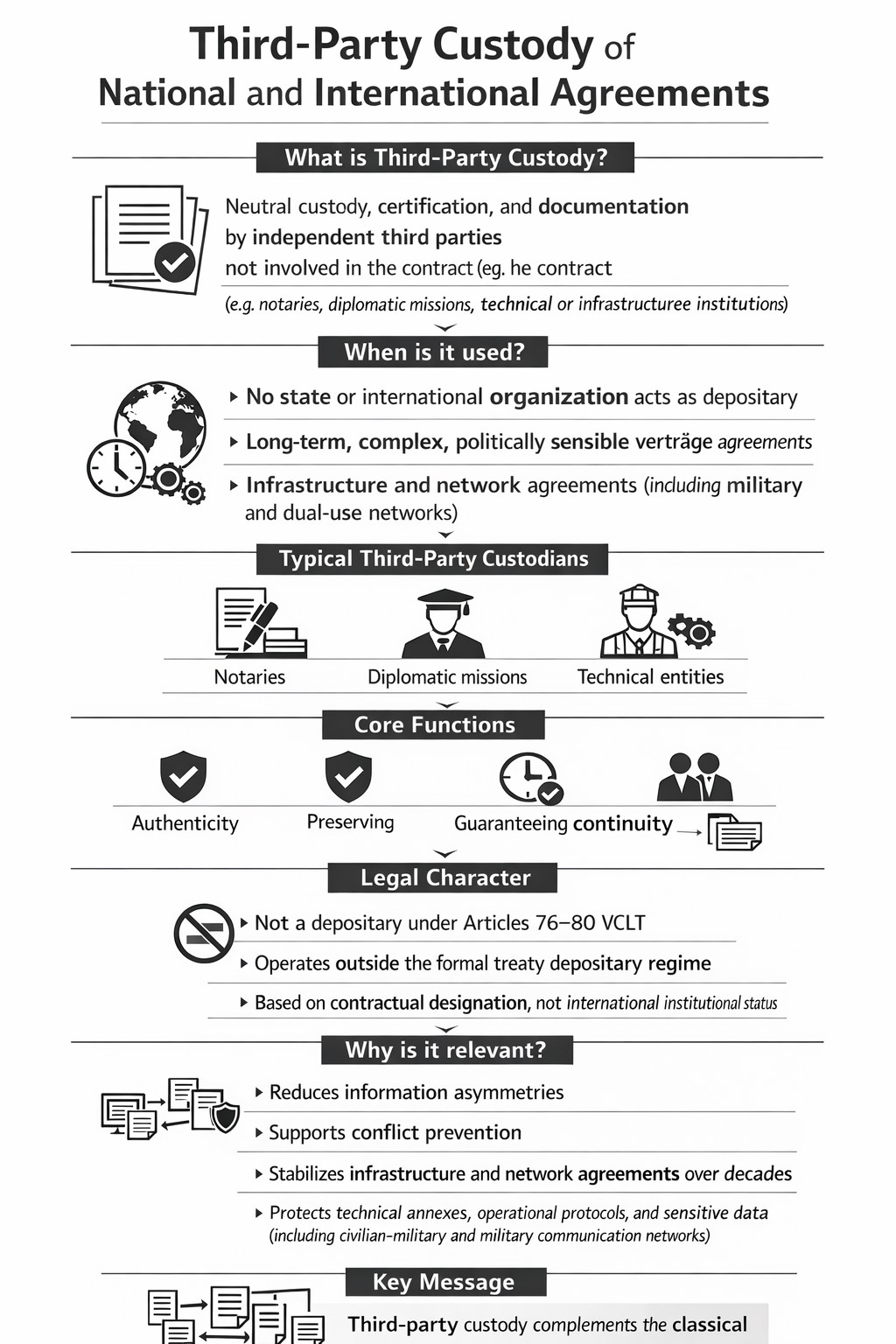

Third‑partyThird‑party custody of national and international agreements custody of national and international agreements reefers to the neutral deposit, authentication, and long - term documentation of treaties by actors outside the contracting parties - most notably notaries, diplomatic missions, or specialised technical custodians. This model becomes essential in cross‑border dual‑use infrastructure agreements, where civilian and military networks intersect and where privateprivate legal entities legal entities participate alongside states. Such arrangements provide crisis‑resilience: if a company becomes insolvent or a state faces bankruptcy, the notarial deposit ensures that source codes, technical annexes, operational protocols, and treaty versions remain authentic, accessible, and legally verifiable. The notary acts as a neutral escrow‑type custodian, safeguarding integrity, continuity, and confidentiality without exercising sovereign authority. This practice is increasingly relevant in global network systems involving dual‑use telecommunications infrastructure, where long‑term stability and neutrality are indispensable. Examples include agreements linked to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), multinational telecom operators such as AT&T or TKS Cable, and worldwide NATO / US Army communications networks, which rely on both military systems and civilian backbone infrastructure. In these contexts, third‑party custody mitigates information asymmetries, prevents disputes, and ensures that technical standards, updates, and contractual obligations remain traceable over decades. It complements - without replacing - the classical treaty depositary functions under international law by offering a flexible, neutral, and legally robust mechanism for safeguarding complex transnational agreements.

Such arrangements provide crisis‑resilience: if a company becomes insolvent or a state faces bankruptcy, the notarial deposit ensures that source codes, technical annexes, operational protocols, and treaty versions remain authentic, accessible, and legally verifiable. The notary acts as a neutral escrow‑type custodian, safeguarding integrity, continuity, and confidentiality without exercising sovereign authority.

This practice is increasingly relevant in global network systems involving dual‑use telecommunications infrastructure, where long‑term stability and neutrality are indispensable. Examples include agreements linked to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), multinational telecom operators such as AT&T or TKS Cable, and worldwide NATO / US Army communications networks, which rely on both military systems and civilian backbone infrastructure.

In these contexts, third‑party custody mitigates information asymmetries, prevents disputes, and ensures that technical standards, updates, and contractual obligations remain traceable over decades. It complements - without replacing - the classical treaty depositary functions under international law by offering a flexible, neutral, and legally robust mechanism for safeguarding complex transnational agreements.

- International Law

- International Treaty

- International Relations

- Treaty Law

- Dispositary

- Custodian

- Notary

- Treaty Chain

- Holy See

- treaty escrow

A. Third-Party Custody of International Agreements

(International Law)

1. Concept and Terminology

Third-partyThird-party custody of international agreements custody of international agreements reefers to the contractually agreed entrustment of treaty instruments, annexes, or related documentation to a neutral entity that is not a depositary within the meaning of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT). Such arrangements are based exclusively on the consent of the contracting parties and operate outside the formal depositary regime of international treaty law.

In contrast to a depositary governed by Articles 76 - 80 VCLT, a third - party custodian does not derive authority from international treaty law itself, but solely from the underlying custody agreement and the applicable legal framework designated therein. As a result, third - party custody constitutes an atypical yet legally permissible mechanism situated at the intersection of international law, contract law, and, in some instances, domestic public law.

Doctrinally, third-party custody must be distinguished from both depositarydepositary institutions under the VCLT institutions under the VCLT and from private - law trust or escrow arrangements, although hybrid configurations may occur in practice.

2. Legal Nature of Third - Party Custody Arrangements

2.1 Contractual Foundation

Third-party custodianship is grounded entirely in party autonomy. International law does not prohibit States or other subjects of international law from designating neutral entities to perform custodial or documentation-related functions, provided that such designation does not purport to create a depositary within the meaning of the VCLT.

Authoritative commentary confirms that custodial functions may lawfully exist outside the VCLT framework, solely by virtue of agreement between the parties, without triggering the legal consequences attached to depositaries under international treaty law.[1]

The legal status, powers, duties, and liability of the custodian are therefore determined by:

- the custody agreement itself,

- the governing law clause,

- and, where applicable, relevant rules of private international law.

2.2 Negative Delimitation vis - à - vis VCLT Depositaries

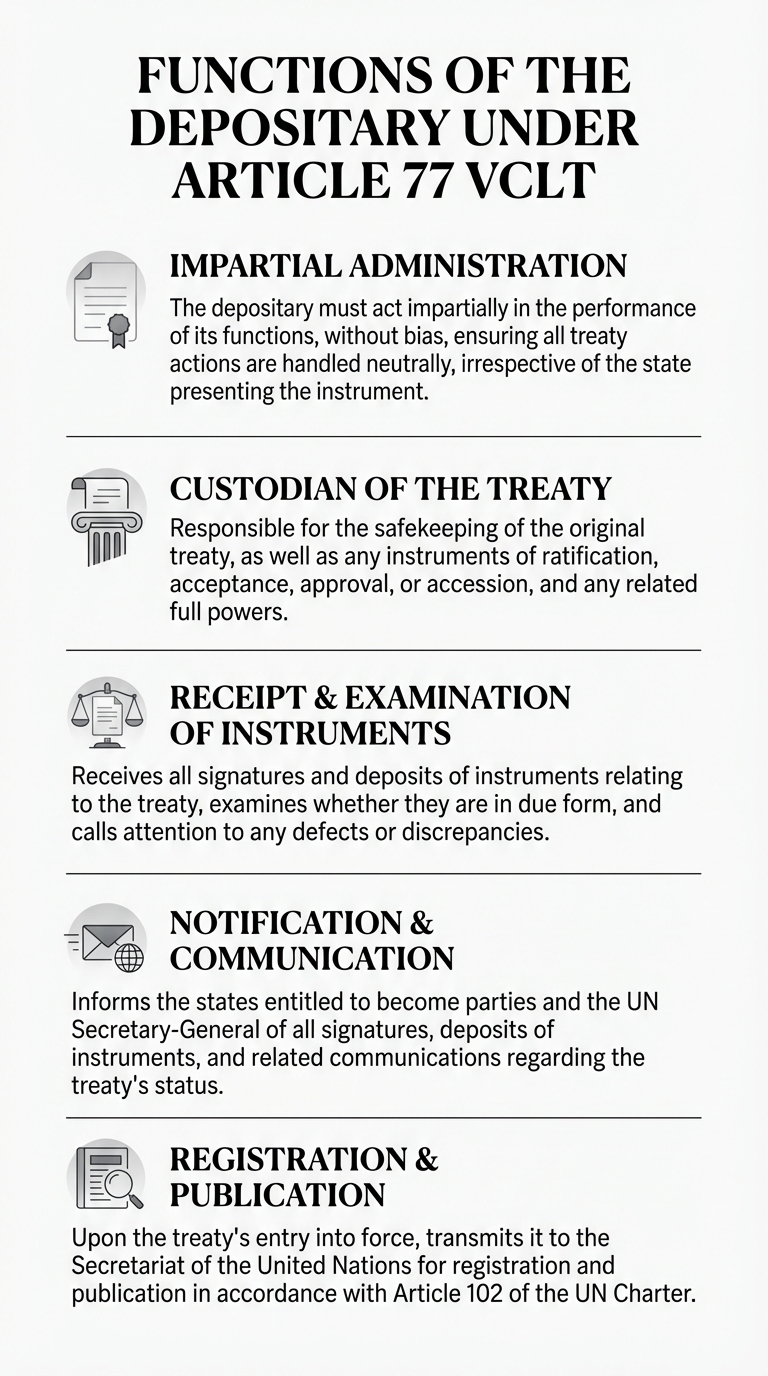

Articles 76–80 VCLT establish the depositary as an institution of international treaty law, performing functions of an international character and subject to a strict obligation of impartiality.[2]

By contrast, third-party custodians:

- do not perform functions “of an international character” within the meaning of Article 76(2) VCLT,

- are not bound by the notification and registration obligations prescribed by the Convention,

- and do not acquire international legal status as depositaries.

The distinction is therefore qualitative, not merely formal. A third-party custodian does not act on behalf of the international legal order, but exclusively on behalf of the contracting parties.

3. Actors Eligible as Third-Party Custodians

3.1. Typical Custodial Actors

State practice and doctrinal analysis identify a limited but diverse range of actors commonly designated as third-party custodians:

- Internationally recognized notaries, particularly in civil - law jurisdictions;

- Diplomatic missions, including embassies acting under protecting-power arrangements;

- Public or private legal persons, such as foundations or specialized custodial entities;

- Neutral institutions with recognized technical or professional expertise.

What unites these actors is not institutional status, but functional suitability, neutrality, and reliability.

3.2. Absence of International Legal Personality

With the exception of diplomatic missions acting as organs of the sending State, third-party custodians typically lack international legal personality. Even where the custodian is a public authority under domestic law, its custodial role does not transform it into a subject of international law.

Accordingly, responsibility for breaches of custodial obligations is assessed under the applicable contractual or domestic legal framework, not under the law of State responsibility.

4. Functional Scope of Third - Party Custody

4.1. Core Custodial Functions

The functions entrusted to third-party custodians commonly include:

- Physical or digital custody of treaty originals or authentic copies;

- Safeguarding of technical annexes, coordinate lists, datasets, or source code;

- Certification of copies and confirmation of authenticity;

- Maintenance of a continuous documentary record of amendments and addenda.

Unlike VCLT depositaries, third-party custodians dodo not examine the validity not examine the validity of instruments of ratification or accession, unless expressly mandated to do so by contract.

4.2. Documentation and Evidentiary Value

A central practical advantage of third-party custody lies in its evidentiary function. Notarial custody, in particular, provides internationally recognized proof of:

- the existence of a document at a specific time,

- its integrity,

- and its certified content.

This evidentiary dimension plays a significant role in technically complex or politically sensitive agreements.

5. Fields of Application

5.1. Technical and Infrastructure Agreements

Third-party custody is frequently employed in agreements concerning:

- telecommunications infrastructure,

- energy networks,

- cross-border data systems,

- and scientific cooperation projects.

In such contexts, custody often extends beyond the treaty text itself to include highlyhighly technical annexes technical annexes whose integrity is essential to the functioning of the agreement.

5.2. Confidential or Politically Sensitive Treaties

Where contracting parties deliberately seek to avoid:

- involvement of international organizations,

- registration under Article 102 of the UN Charter,

- or public disclosure,

third-party custody offers a legally secure yet discreet alternative.

5.3. Hybrid Public - Private Arrangements

Agreements involving both States and private actors frequently rely on third-party custodians to manage documentation and technical assets, particularly where insolvency risks or long-term continuity must be addressed.

6. Doctrinal Classification

From a systematic perspective, third-party custody occupies an intermediate doctrinal space:

- it is not an institution of international treaty law,

- but it is not purely private where States are involved.

International legal doctrine therefore classifies it as a permissible ancillary mechanism, compatible with treaty law but external to its formal institutions.[3]

7. Preliminary Assessment

Third-party custody represents a functionalfunctional response to structural limitations response to structural limitations of the classical depositary system. Its legitimacy derives from:

- party autonomy,

- the absence of prohibitive norms,

- and consistent State practice.

At the same time, its contractual nature necessitates careful drafting to avoid confusion with depositary functions under the VCLT.

B. Institutional and Non - Institutional Forms of Third - Party Custody

8. Diplomatic Missions as Third - Party Custodians

8.1. Diplomatic Custody Outside the VCLT Framework

Diplomatic missions have historically performed custodial functions in international relations, particularly in bilateral contexts where no international organization was designated as depositary. Although diplomatic missions are not depositaries within the meaning of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, their role as custodians is well established in practice and doctrine.

Such custodial arrangements are typically non-institutional and arise either from express treaty clauses or from supplementary diplomatic agreements. The embassy or mission acts as a neutral repository for treaty instruments, amendments, maps, or technical protocols, ensuring continuity of documentation without assuming depositary status under international law.[4]

8.2. Typical Fields of Diplomatic Custody

Diplomatic missions are most frequently entrusted with custodial functions in relation to:

- Treaty addenda and protocols,

- Bilateral border agreements, particularly those involving cartographic material,

- Technical cooperation agreements, including infrastructure or transport arrangements.

In these contexts, diplomatic custody serves pragmatic objectives, allowing States to manage treaty documentation efficiently without resorting to international institutions or third-party organizations.[5]

8.3. Legal Limitations of Diplomatic Custodianship

While diplomatic missions may receive instruments, issue certified copies, and maintain an unbroken documentary record, their custodial role remains strictly ancillary. They do not acquire authority to verify the validity of ratifications or accessions, nor do they perform notification functions under Articles 77 and 78 VCLT unless expressly mandated by the parties.

Doctrinal consensus emphasizes that diplomatic custodianship is procedural rather than normative: it facilitates treaty administration without creating legal effects beyond those intended by the parties.[6]

9. Notaries as Third - Party Custodians

9.1. Professional Suitability of Notaries

Notaries, particularly within civil - law systems, are professionally equipped to assume custodial functions in international agreements characterized by mixed public - private elements. Their traditional functions - authentication, certification, and secure preservation of documents - align closely with the practical needs of third-party custody.

International practice demonstrates that notarial custody is particularly suitable where agreements involve:

- States and non - State actors,

- private - law components,

- or technically complex annexes requiring long-term integrity.[7]

9.2. Notarial Custody and Evidentiary Authority

A defining feature of notarial custody is its evidentiary strength. Notarial deeds certifying the deposit of treaty-related materials are widely recognized as probative evidence of existence, content, and integrity at a given point in time.

However, it is essential to emphasize that notaries possess no independent authority under international law. Their functions arise exclusively from contractual arrangements and are governed by domestic law, even when the subject matter concerns international agreements.[8]

9.3. Notarial Custody of Technical Annexes

An increasingly significant area of application is the custody of technical or scientific annexes. Environmental agreements, telecommunications treaties, and infrastructure projects often rely on datasets, standards, or digital reference materials whose manipulation could have far - reaching consequences.

In such cases, notarial custody provides a neutral safeguard, separating technical documentation from political discretion and ensuring legal certainty throughout the treaty’s lifespan.[9]

10. Escrow - Like Arrangements and Hybrid Models

10.1. Escrow Functions in International Agreements

Certain third-party custodial arrangements incorporate escrow mechanisms, particularly where sensitive technology or proprietary information is involved. Typical examples include the deposit of software source code essential for governmental infrastructure systems.

Under such arrangements, the custodian is instructed to release the deposited material only upon the occurrence of predefined conditions, such as the insolvency of a supplier.[10]

10.2. Doctrinal Delimitation from Depositary Functions

Despite functional similarities, escrow arrangements must be distinguished from depositary functions under the VCLT. Unlike depositaries, escrow agents exercise conditional dispositive authority, albeit within narrowly defined contractual parameters.

Doctrine therefore classifies escrow arrangements as hybrid constructs, combining elements of custody with conditional performance, but remaining external to the treaty - law framework of the VCLT.[11]

11. Multilateral Contexts and Specialized Custodians

11.1. Custody in Multilateral Environmental and Technical Regimes

In multilateral regimes, particularly those administered by United Nations specialized agencies, custody of technical annexes and reference materials is often decentralized. Neutral third-party custodians may be entrusted with maintaining updated datasets or reference samples essential to treaty compliance.

Such practices are especially prevalent in environmental law and telecommunications regulation, where technical complexity necessitates specialized custodial expertise.[12]

11.2. Functional Complementarity with International Organizations

Third - party custody does not replace institutional depositaries but rather complements them. While international organizations retain responsibility for treaty administration and compliance mechanisms, third-party custodians provide technical neutrality and evidentiary reliability.

This functional complementarity underscores the adaptability of international treaty practice to evolving technical and political challenges.[13]

12. Systematic Implications for International Treaty Law

From a systematic perspective, third-party custody reflects the flexibilizationflexibilization of treaty practice of treaty practice without undermining the normative core of the VCLT. It demonstrates how party autonomy and contractual innovation operate within the broader framework of international law.

At the same time, the absence of formal regulation necessitates careful doctrinal delimitation to prevent confusion between contractual custody and depositary functions governed by treaty law.[14]

C. Systematic Evaluation, De Lege Lata and De Lege Ferenda Perspectives, and Special Cases

13. Systematic Assessment De Lege Lata

Under existing international law (de lege lata), third-party custody of international agreements is lawful and compatible with the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, provided that such arrangements do not purport to establish a depositary within the meaning of Articles 76–80 VCLT.

The Convention deliberately refrains from restricting the category of actors that may physically or administratively safeguard treaty documentation, as long as the legally relevant depositary functions remain clearly distinguished. The prevailing view in doctrine confirms that third-party custodianship constitutes a permissible ancillary mechanism, grounded in the principle of State consent and party autonomy.[15]

Crucially, third-party custodians:

- do not perform functions “of an international character” within Article 76(2) VCLT,

- do not incur obligations erga omnes partes,

- and do not exercise authority attributable to the international legal order.

Accordingly, their acts neither generate nor modify treaty relations as such, but merely support the technical administration of treaty instruments.[16]

14. Systematic Assessment De Lege Ferenda

From a de lege ferenda perspective, third-party custody responds to structural developments in contemporary treaty practice. Increasing technological complexity, the involvement of private actors, and geopolitical fragmentation have exposed practical limits of centralized depositary systems.

Scholarly analysis suggests that the continued expansion of third-party custody does not require formal codification, but rather conceptualconceptual consolidation consolidation through:

- clearer contractual standard clauses,

- express exclusion of VCLT depositary status,

- and enhanced safeguards for neutrality and evidentiary reliability.[17]

Formal amendment of the VCLT has been widely regarded as unnecessary and potentially counterproductive, given the Convention’s functional flexibility and the absence of normative conflict with existing practice.[18]

15. Delimitation from Trust and Escrow Models

15.1. Distinction from Trust Arrangements

Third-party custodianship must be strictly distinguished from trust arrangements known in domestic private law. While trustees exercise discretionary authority in the interest of beneficiaries, third-party custodians act without discretion, performing purely administrative and preservative functions.

Trust relationships are inherently fiduciary and interest-oriented, whereas third-party custody under international agreements is functionallyfunctionally neutral neutral and normatively detached from substantive treaty obligations.[19]

15.2. Distinction from Escrow Mechanisms

Escrow mechanisms, frequently employed in technology-related agreements, occupy a hybrid position. Although escrow agents may also act neutrally, they are empowered to release deposited material upon the occurrence of predefined conditions.

This conditional dispositive authority marks a decisive doctrinal boundary. Unlike escrow agents, third-party custodians under international agreements do not control access to treaty obligations or their performance, unless such authority is explicitly and separately conferred.

Doctrine therefore treats escrow arrangements as contractual risk - management tools, rather than as components of international treaty law.[20]

16. The Holy See as a Special Case of Third - Party Custody

16.1. International Legal Personality of the Holy See

The Holy See represents a unique case in international law, possessing international legal personality independent of the Vatican City State. This status enables it to conclude treaties, primarily in the form of concordats, and to participate in multilateral agreements.

Its legal personality and moral authority position the Holy See as a potentially suitable neutral custodian for agreements concerning ethical, humanitarian, or religious matters.

16.2. Custodial Suitability and Doctrinal Limits

While the Holy See is not traditionally designated as a depositary, doctrinal analysis suggests that nothing in international law precludes its designation as a third-party custodian, provided that:

- its role is contractually defined,

- depositary functions under the VCLT are expressly excluded,

- and custodial neutrality is preserved.

The distinction between the Holy See and the Vatican City State remains essential: physical custody may be exercised within Vatican territory, while legal acts are attributable to the Holy See as a subject of international law.[21]

17. Practical Advantages and Structural Risks

17.1. Advantages

Third-party custody offers several practical advantages:

- enhanced neutrality in politically sensitive contexts,

- flexibility outside institutional frameworks,

- and high evidentiary reliability for technical annexes.

These features explain its growing use across diverse fields of international cooperation.

17.2. Structural Risks

At the same time, the absence of standardized regulation poses risks, including:

- potential confusion with VCLT depositary functions,

- uncertainty regarding applicable law and jurisdiction,

- and fragmentation of documentation practices.

These risks underscore the need for precise contractual drafting and doctrinal clarity.[22]

18. Observations

Third-party custody of international agreements illustrates the adaptability of international treaty practice to contemporary challenges. Situated outside the formal framework of the VCLT yet fully compatible with it, third-party custodianship operates as a functionalfunctional supplement supplement rather than an alternative to classical depositary systems.

Its legitimacy rests on consent, neutrality, and technical reliability. As long as these principles are respected, third-party custody is likely to remain a durable feature of international legal practice.

D. Special Case:

Notary as Neutral Custodian in Public International Law: Infrastructure Networks, Dual - Use, and Insolvency Safeguarding

(In particular, with the involvement of the ITU (UN) and military-civilian network providers such as TKS Cable)

(In particular, with the involvement of the ITU (UN) and military-civilian network providers such as TKS Cable)

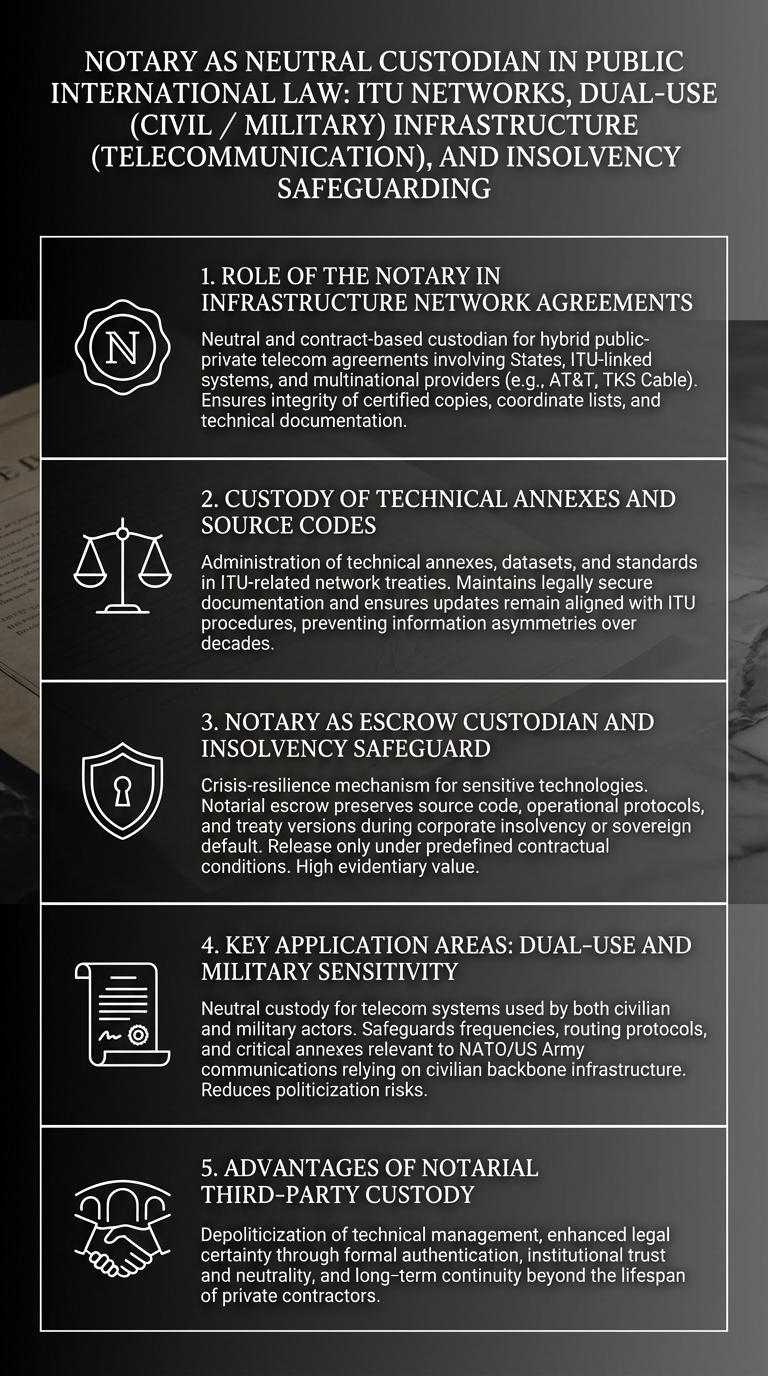

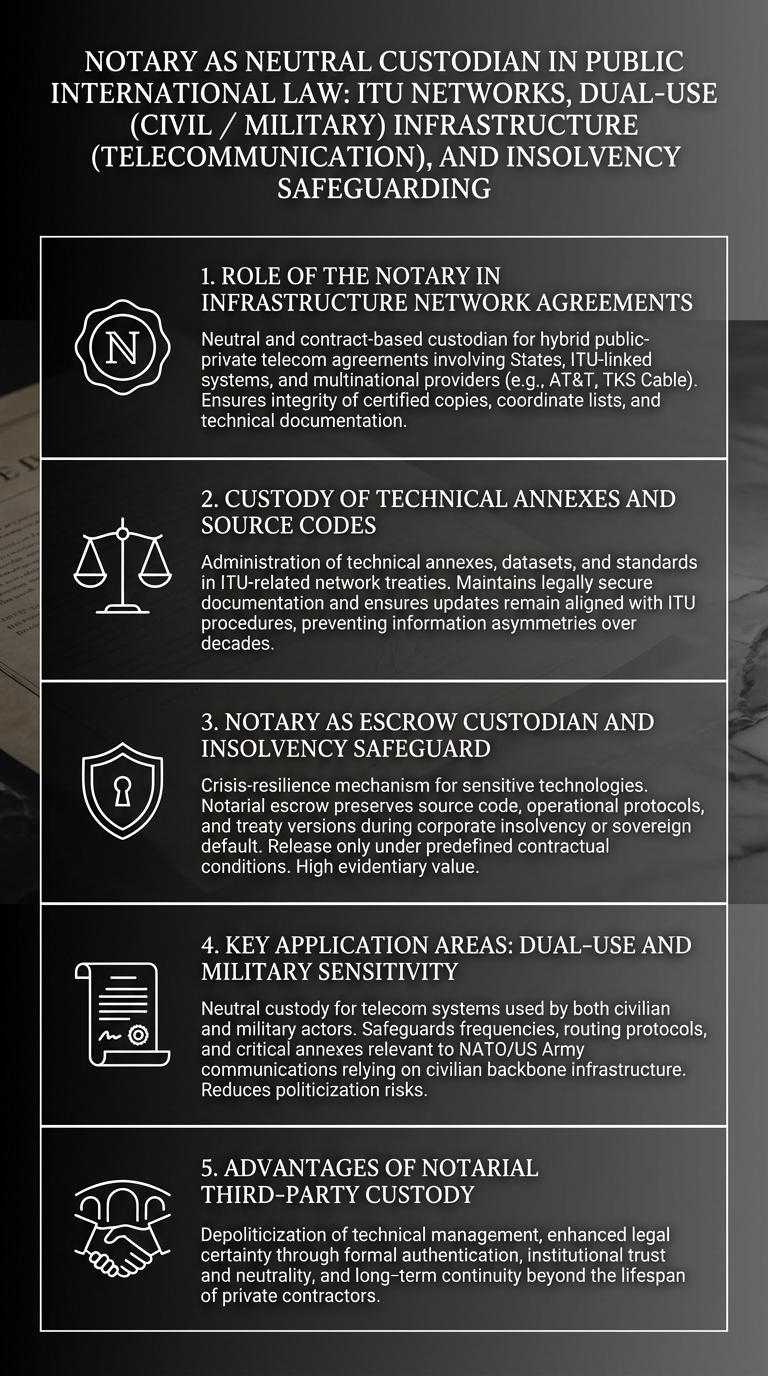

19. The Role of the Notary in Infrastructure Network Agreements

19. The Role of the Notary in Infrastructure Network Agreements

In the contemporary landscape of Public International Law, infrastructure agreements - particularly those involving telecommunications and global network systems - frequently involve a convergence of State actors and private legal entities, such as multinational providers like AT&T or TKS Cable. In these mixed public-private (hybrid) constellations, the notary serves as a neutral, independent, and reliable custodian mandated by the parties.[23][24]

The notarial intervention is particularly suitable for treaties containing private-law elements or complex commercial annexes, especially where agreements involve both sovereign States and non-State actors.[25][26] The notary’s functions include the administration of certified copies, coordinate lists, and technical documentation.[27] It is important to note that the notary does not exercise autonomous international authority; rather, their competence derives solely from the contractual delegation by the parties (party autonomy).[28][27]

20. Custody of Technical Annexes and Source Codes

Global contractual chains in the telecommunications sector require the administration of vast datasets and technical standards.[29][30] In the context of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), notaries can act as custodians for technical annexes to international network agreements.[31][32] They provide legally secure documentation and ensure that continuous updates remain aligned with ITU procedures.[33] This prevents information asymmetries and ensures that the technical "heart" of the agreement remains verifiable over decades.[34]

21. The Notary as an Escrow Custodian and Insolvency Safeguard

The use of notarial escrow is a critical mechanism for safeguarding sensitive technologies.[35] A primary application is source-code escrow for State infrastructure systems.[36] This function provides a robust "crisis-resilience" framework:

- Insolvency Safeguards: In the event of a company’s insolvency or a State’s sovereign default, the notarial deposit ensures that critical source codes, operational protocols, and treaty versions remain authentic and accessible.[37]

- Release Conditions: The notary ensures that sensitive data is released only under strictly predefined contractual conditions, protecting the continuity of vital infrastructure.[38][39]

- Evidentiary Value: The notarial instrument serves as internationally recognized evidence of the existence and integrity of the deposited documents.[40]

22. Key Application Areas: Dual - Use and Military Sensitivity

The necessity for neutral custodianship is most evident in global network systems with dual-use characteristics - infrastructure shared by both civilian and military users.[41]

- ITU-Based Telecom Agreements: Safeguarding technical specifications and digital reference data to ensure long-term traceability.[42][43]

- Dual-Use Networks: Neutral custody of sensitive parameters such as frequencies and routing protocols.[44] This is essential for multinational cooperation (e.g., NATO / US Army communications) where military systems rely on civilian backbone infrastructure.[45]

- Security-Sensitive Contexts: Custody of critical annexes related to radar or sensor systems.[46] Depoliticized custodianship mitigates the risk of technical data being used as political leverage.[47][48]

23. Advantages of Notarial Third - Party Custody

Compared to purely private escrow providers or classic state-led depositaries, the notarial model offers distinct advantages:[49][50]

- Depoliticization: It removes the management of technical details from political discretion.[51][52]

- Legal Certainty: Enhanced protection through formal authentication requirements.[25][53]

- Trust and Neutrality: As an office of public trust, the notary provides higher institutional stability.[54][55]

- Continuity: Essential for long-term infrastructure projects where the lifespan of the agreement exceeds the corporate existence of the contractors.[56]

24. Example: International Treaty Deed, Roll 1400/98.

(German: Kaufvertrag, Urkundenrolle 1400/98, dated October 6, 1998)

Concluded between the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), the Kingdom of the Netherlands, NATO (Dutch Air Force), TKS Cable, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU, United Nations), and additional actors within the broader treaty chain.

Concluded between the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), the Kingdom of the Netherlands, NATO (Dutch Air Force), TKS Cable, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU, United Nations), and additional actors within the broader treaty chain.

[57]

This entry presents an example from contemporary treaty practice in Public International Law. It links to an international agreement concerning a NATONATO installation installation in Germany[58], formerly used under the NATONATO (SOFA) Status of Forces Agreement (NATO Truppenstatut) (SOFA) Status of Forces Agreement (NATO Truppenstatut) by UnitedUnited States forces States forces and, in part, by the Royal Netherlands Air Force. In this context, the parties designated a notarynotary (in Saarlouis , FRG) as a neutral custodian (in Saarlouis , FRG) as a neutral custodian for the treaty. The agreement involved telecommunications services supplied by TKS Telepost in cooperation with AT&T, operating within the legal framework (Treaty Chain) of ITU,ITU, NATO - UN, SOFA NATO - UN, SOFA and HostHost Nation Support (HNS) Nation Support (HNS) arrrrangements, which permit militarymilitary and authorised civilian providers and authorised civilian providers to ao access and utilise civilian infrastructure for operational purposes.

25. Conclusion

Third‑party custody provides a neutral, contract‑based way to safeguard treaties and technical documentation outside the VCLT system. By relying on notaries, diplomatic missions, or specialised custodians, it ensures continuity, integrity, and confidentiality in complex or dual‑use agreements, complementing - but not replacing - classical depositary functions.

References

- Oliver Dörr & Kirsten. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary; Springer: Germany , 2018; pp. Art. 76 paras. 6–9, pp. 1303–1306.

- Christina Binder; Mark Eugen Villiger, Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Leiden and Boston, 2009, ISBN 9789004168046, xxxiv + 1058 pp., EUR 240.00. Austrian Rev. Int. Eur. Law Online. 2013, 15, Art. 76 paras. 1–4, pp. 1714–1719.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013; pp. ch. 11, pp. 312–315.

- Eileen Denza. Diplomatic Law: Commentary on the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2008; pp. Art. 3 paras. 15–20, pp. 75–82.

- Comment By Jill Barrett. Anthony Aust, The Theory and Practice of Informal International Instruments, 1986; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. pp. 801–805.

- Shabtai Rosenne; The Depositary of International Treaties. Am. J. Int. Law. 1967, 61, pp. 928–930.

- Jeremy Hill. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary; Oxford University Press: UK, 2022; pp. Art. 77 paras. 8–11, pp. 1142–1146.

- T. O. Elias. Problems concerning the validity of treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. ch. 12, pp. 245–248.

- Maria Ivanova. United Nations Environment Programme; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, United States, 2022; pp. 1-8.

- Christopher Millard; Software escrow arrangements and the insolvency act 1986. Comput. Law Secur. Rev.. 1989, 4, 18-20.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013; pp. pp. 386–389.

- Silvio Ferrari. The Vatican and International Relations; Cambridge University Press: UK, 2019; pp. pp. 65–72.

- Christina Binder; Mark Eugen Villiger, Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Leiden and Boston, 2009, ISBN 9789004168046, xxxiv + 1058 pp., EUR 240.00. Austrian Rev. Int. Eur. Law Online. 2013, 15, 1735–1739.

- Oliver Dörr. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary; Kirsten Schmalenbach, Eds.; Springer: Germany , 2018; pp. Art. 77 paras. 12–15, pp. 1318–1322.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013; pp. pp. 352–360.

- Mark E. Villiger. Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. Art. 76 paras. 1–4, pp. 1714–1719.

- Klein Corten. The Vienna Conventions on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2011; pp. 20–26.

- Oliver Dörr. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary; Kirsten Schmalenbach, Eds.; Springer: Germany , 2018; pp. Art. 76 paras. 12–15, pp. 1309–1312.

- J. Basedow. Encyclopedia of Private International Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham Glos, United Kingdom, 2017; pp. pp. 1805–1810.

- T. O. Elias. Problems concerning the validity of treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. pp. 245–248.

- Malcolm N. Shaw. International Law, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press: UK, 2014; pp. 9.25–9.30.

- Shabtai Rosenne; The Depositary of International Treaties. Am. J. Int. Law. 1967, 61, pp. 930–933.

- Michael Richtsteig. Wiener Übereinkommen über diplomatische und konsularische Beziehungen; Nomos Verlag: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2010; pp. 1087–1089.

- Alfred Verdross; Bruno Simma. Universelles Völkerrecht. Theorie und Praxis.; Duncker & Humblot GmbH: Berlin, DE, Germany, 2010; pp. 515–516.

- Mark E. Villiger. Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 1714 ff..

- Isabella Risini; Mark E. Villiger: Handbuch der Europäischen Menschenrechtskonvention (EMRK): mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Rechtsprechung des Europäischen Gerichtshofs für Menschenrechte in Schweizer Fällen, 3. Auflage, Baden-Baden, Nomos, 2020, 634 S.. null. 2020, 58, Art. 77, Rn. 10–12.

- Mark E. Villiger. Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. Art. 76, Rn. 10–12.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013; pp. 352–360.

- ITU-T Recommendation Y.2205: Next Generation Networks – Emergency telecommunications.. ITU.int. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- ITU-T Y-Series Recommendations: Global information infrastructure and next-generation networks.. ITU.int. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- Jale Tosun. Energy Policy; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2017; pp. Rn. 12–18.

- Fedlex: Übereinkommen über die Vorrechte und Befreiungen der Sonderorganisationen.. Fedlex.admin.ch. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- United Nations Treaty Collection: Treaty Handbook. S. 17–25. Treaties.un.org. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- Sienho Yee; The Law of Treaties Beyond the Vienna Convention. Chin. J. Int. Law. 2012, 11, 367-368.

- Software escrow, source code escrow, SaaS escrow – what's the difference?. Codekeeper.co. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- Tooba Faisal et al.: BEAT: Blockchain-Enabled Accountable and Transparent Network Sharing in 6G. 2022. Arxiv.org. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- Mark Broom; David Collins; Trung Hieu Vu; Philip Thomas; The four regions in settlement space: a game-theoretical approach to investment treaty arbitration. Part II: cases. Law, Probab. Risk. 2018, 17, 3-7.

- Mark Broom; David Collins; Trung Hieu Vu; Philip Thomas; The four regions in settlement space: a game-theoretical approach to investment treaty arbitration. Part II: cases. Law, Probab. Risk. 2018, 17, 3-9.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2007; pp. 386–389.

- Klein Corten. The Vienna Conventions on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2011; pp. Article 77 – Rn. 6–14, Rn. 3–7, 24–27.

- Denise Garcia. Disarmament in International Law; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2020; pp. Rn. 6–9.

- International telecommunication law. CCDCOE, 2021. Cyberlaw.ccdcoe.org. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- United Nations Treaty Collection: Summary of Practice. S. 62–64. Treaties.un.org. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- Denise Garcia. Disarmament in International Law; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2020; pp. Rn. 1–4, 9–11.

- OPCW Basics: Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. OPCW.org. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- International Committee of the Red Cross. Commentary on the First Geneva Convention; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2016; pp. Rn. 77–85.

- Anthony Aust; The Theory and Practice of Informal International Instruments. Int. Comp. Law Q.. 1986, 35, 787-812.

- Anthony Aust; The Theory and Practice of Informal International Instruments. Int. Comp. Law Q.. 1986, 35, 803–805.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013; pp. 283.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2007; pp. 318–322.

- Shabtai Rosenne; The Depositary of International Treaties. Am. J. Int. Law. 1967, 61, 923–933.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2007; pp. 380–385.

- Mark E. Villiger. Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 925–928.

- Elgar. Encyclopedia of Private International Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham Glos, United Kingdom, 2017; pp. 1805–1810.

- Viktor Bruns; Fritz Poetzsch-Heffter. Jahrbuch des Öffentlichen Rechts der Gegenwart; Mohr Siebeck: Tubingen, Germany, 2025; pp. 77–90.

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2013; pp. 380–389.

- Kaufvertrag Urkundenrolle 1400/98. Archive.org. Retrieved 2026-1-12

- NATO - Turenne Caserne, FRG. Wikipedia . Retrieved 2026-1-12