Definition of Treaty Chains & Depositaries and Third‑Party Custodians

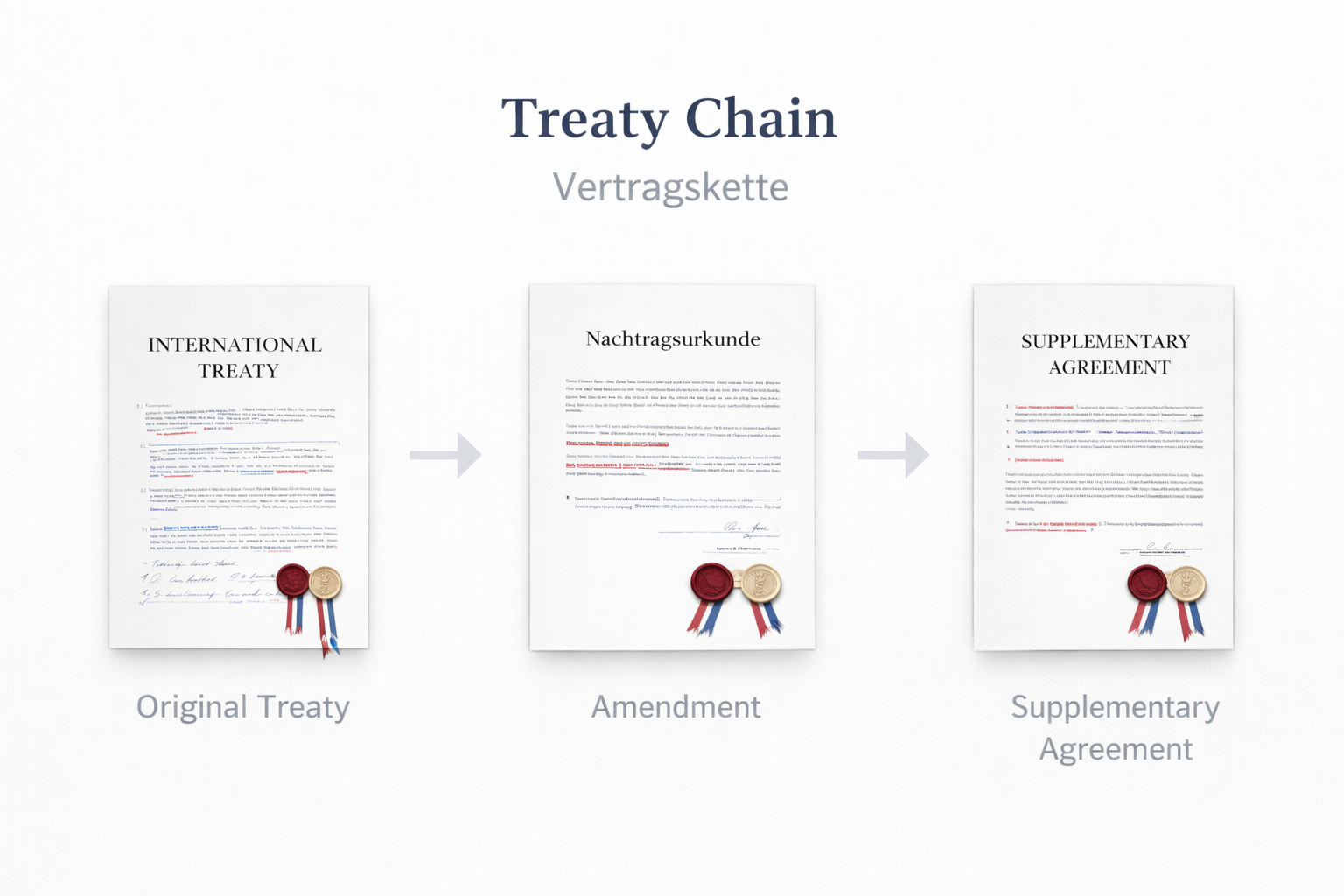

A treaty chain denotes the cumulative body of an original treaty and all subsequent agreements, amendments, supplementary instruments, interpretative practices, and implied modifications that together constitute the operative legal framework in national and international law. Domestic systems (BGB, OR, ABGB) recognise that later agreements - whether explicit, written, or implied through consistent conduct - extend and modify the original contract, forming a unified normative sequence. Common law similarly incorporates subsequent modifications through course of dealing, implied terms, and promissory estoppel.

In international law, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties structures treaty chains through rules on consent, amendment, priority of later treaties, and depositary practice.

Supplementary instruments update obligations without creating new treaties, while acquiescence and partial performance may constitute tacit consent where behaviour clearly indicates acceptance.

Depositaries ensure registration, authentication, notification, and archival continuity. Beyond classical institutional depositaries classical institutional depositaries (UN, NATO)(UN, NATO), treaty practice also recognises neutral third‑party depositaries - such as notaries, diplomatic missions, or independent technical bodies - particularly for multilateral agreements requiring strict neutrality.

This is common in cross‑border infrastructure regimes (energy grids, data networks, transport corridors), where states seek a politically neutral custodian to guarantee procedural integrity, equal access to documentation, and long‑term stability of the treaty chain. Such third‑party depositaries provide impartial verification, secure custody of amendments and supplementary instruments, and continuity even where political relations fluctuate.

Treaty chains thus ensure legal stability, Treaty chains thus ensure legal stability, adaptability, and coherent development of obligations across time and jurisdictions.

- International Law

- Domestic Law

- Law

- International Treaty

- Treaty Chain

- Chain of Contracts

- International Relations

- Depositary

- Third-party Depositary

- international treaty law

The treaty chain in national and international law

1. Treaty Chain

Treaty Chain

A “chain of contracts” / "treaty chain" refers, in both national law and international law, to the entirety of all successive agreements, amendments, supplements, and ancillary instruments that together constitute the applicable contractual content.[1] This also applies when reference is made to other treaties (or treaty chains), for example to the NATO Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA).[2]

- When an international treaty refers to other treaties or treaty chains, this activates the entire SOFA treaty chain (NTS, the NTS Supplementary Agreement, the HNS Agreement, etc.).[3][4]

Such a treaty chain arises when an original treaty is further developed through subsequent arrangements without concluding an entirely new treaty.[5]

Contract Chain in National Law

2. Contract Chain in National Law

In national legal systems - such as German, Austrian, or Swiss civil law - a contract chain comprises all subsequent agreements that modify or supplement the original contract.[6]

These include:

- amendment agreements,

- supplementary agreements,

- addenda, additional clauses, and protocol notes,

- implied modifications through actual conduct.[7]

- When reference is made to other contracts, these become part of the new agreement. This also includes the activation of such an external contract chain.[8]

Under German law, this follows from the general principles of contractual freedom and contract interpretation (sections 133 and 157 BGB).[9] Later agreements take precedence over earlier ones; the contract chain forms the decisive basis for interpreting the legal relationship (section 311 BGB).[10] The same applies under Swiss law (Arts. 1-18 OR) and Austrian law (especially sections 863 and 914 ABGB), where subsequent arrangements continue the contractual content.[11][12]

Implied (Tacit) Contract Modification in National Law

3. Implied (Tacit) Contract Modification in National Law

A contract may also be modified through actual conduct if such conduct clearly reveals the intention to continue the contract in its modified form. This is referred to as an implied contract modification or “tacit modification”.

The case law recognizes such modifications when:

- the conduct is clear and unequivocal,[13]

- both parties know and accept it,

- it clearly replaces or supplements the previous contractual content.

Examples from National Legal Systems

4. Examples from National Legal Systems

Germany (BGB)

Under German law, the contract chain follows from the principles of contractual freedom and contract interpretation. A contract chain is created through all subsequent agreements that modify or supplement the original contract.

The relevant legal bases include in particular:

- Sections 133 and 157 BGB - interpretation according to the true intention of the parties and good faith; later arrangements must be taken into account when interpreting the contract.[14]

- Section 311 BGB - establishment and modification of obligations.

- Section 305b BGB - precedence of individually negotiated terms over earlier standard terms (AGB provisions).

Example: A residential lease is further developed through several written addenda (e.g., stepped rent, pet keeping, parking space) as well as through implied conduct (e.g., years of tolerated use). All provisions together constitute the contract chain.

Switzerland (OR)

Swiss contract law (the Swiss Code of Obligations) expressly recognizes the continuation and further development of contracts. It recognizes contract chains arising from subsequent arrangements and implied (tacit) modifications.

- Art. 1 OR - conclusion of a contract through mutual expression of intent, including tacitly.

- Art. 2 OR - contractual binding through conduct.

- Art. 18 OR - interpretation according to the parties’ common actual intent.

Example: A service contract is further developed through repeated adjustments to remuneration and working methods, which both parties accept over an extended period. These tacitly agreed modifications become part of the contract chain.

Austria (ABGB)

The Austrian Civil Code (ABGB) expressly recognizes the continuation of contracts and implied (tacit) modifications.

- Section 863 ABGB - contracts may be concluded or modified expressly or implicitly.

- Section 914 ABGB - interpretation according to the parties’ intent and established commercial practice.

- Section 915 ABGB - rule of interpretation in favour of the party that did not draft the clause.

Example: A contract for work and services is expanded through subsequent additional orders, price adjustments, and implied conduct (e.g., acceptance of additional services without objection). These arrangements together form a unified contract chain.

Common Law (UK/USA)

5. Common Law (UK/USA)

In common law systems, the contract chain is formed through the principles of “subsequent agreements” and “course of dealing”.

- Course of dealing - repeated conduct between the parties may modify contractual content.

- Implied terms - contractual terms may be derived from conduct, trade usage, or necessity.

- Subsequent modification - later modifications are possible despite the parol evidence rule.

- Promissory estoppel - binding effect despite the absence of consideration.

- Parol evidence rule (exceptions) - later agreements may modify written contracts when they qualify as a “subsequent modification”.

- Consideration - modifications generally require consideration, except under promissory estoppel or UCC rules (USA).

Example: A supply contract is further developed through repeated practice (e.g., modified delivery times, accepted quality standards). These “course of dealing” elements are treated as part of the contract and form a contract chain.[15]

Supplementary Instrument

6. Supplementary Instrument

A supplementary instrument is an additional or modifying document that continues or updates an existing treaty or contract without creating a new one.[16] It forms part of the treaty chain and produces legal effect only in conjunction with the original treaty.[16]

Supplementary instruments are used in both national and international law to introduce technical, organisational, or legal adjustments without renegotiating the entire treaty.[17][18]

Treaty Chain in International Law

7. Treaty Chain in International Law

In international law, the treaty chain is structured by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT).[19]

Key provisions include:

- Article 11 VCLT - forms of expressing consent (ratification, acceptance, approval, accession, or “any other agreed means”).

- Article 24 VCLT - entry into force of treaties and amendments.

- Article 30 VCLT - priority of later treaties (lex posterior derogat legi priori).

- Article 39 VCLT - general rule regarding treaty amendments.

- Article 40 VCLT - amendment of multilateral treaties.

A supplementary instrument under international law requires ratification only if this is expressly provided for in the new instrument.[20] Otherwise, the ratification, the names of all treaty parties, and the signature are carried over from the treaty chain.[21][22][23]

These rules result in later agreements taking precedence over earlier ones and jointly forming an international treaty chain.[17]

Implied Participation in a Treaty through Partial Performance

8. Implied Participation in a Treaty through Partial Performance

Participation in a treaty under international law may also occur through conduct consistent with the treaty; partial performance that clearly fulfils the purpose and essential obligations of a treaty is regarded as consent and gives rise to the duty of full performance.[24][25][26][27] Implied conduct replaces an express declaration of intent where no other form of consent has been agreed and the conduct clearly indicates the application of the treaty.[28][29]

Acquiescence

9. Acquiescence

In international law, acquiescence refers to the tacit consent of a state through the absence of objection or through conduct consistent with the treaty. It operates as implied consent and may lead to being bound by a treaty or a treaty modification when the state in fact applies the treaty or tolerates its implementation.[30][31][32]

The case law of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) recognizes acquiescence as a form of consent when the conduct of a state clearly indicates recognition or acceptance of a legal situation.[33][34] Acquiescence may in particular be regarded as implied participation in a treaty when a state continues or partially applies a treaty.[35][36]

Depositing and Custody

10. Depositing and Custody

Supplementary instruments and treaty amendments are deposited with the depositary designated in the original treaty.[37]

This may be:

- an international organisation (e.g., the United Nations or NATO),[38]

- a contracting state,[39]

- a neutral third entity (e.g., a notary or a diplomatic mission).[17]

The depositary is responsible for registration, archiving, and notification to the treaty parties.[40][41]

Depositary Practice

11. Depositary Practice

Depositary practice governs the functions of the depositary of an international treaty. The depositary is responsible for the registration, archiving, notification, and administration of treaty instruments, ratifications, accessions, and supplementary instruments.

Typical forms of depositaries include:

- UN depositary - the Secretary‑General of the United Nations acts as depositary for several hundred multilateral treaties.

- NATO depositary - for NATO treaties such as the NATO Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), the NATO Secretary‑General acts as the depositary.[42]

- Multiple depositaries - some treaties designate several depositaries simultaneously, such as regional organisations or multiple contracting states.[43][44]

Depositary practice ensures that treaty chains - including supplementary instruments, protocols, and amendments - are properly documented and communicated to the treaty parties.[17]

Significance

12. Significance

Treaty chains enable the continuous further development of treaties in both national and international law without requiring a complete renegotiation.

They ensure:

- flexibility,

- legal continuity,

- adaptability to new technical or political developments.

Supplementary instruments are a central tool for updating treaties efficiently and with legal certainty.[45][46]

References

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Aust , Eds.; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2007; pp. 87-113.

- NATO Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), 1951. United Nations Treaty Series. NATO . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Protocol on the Status of International Military Headquarters (Paris Protocol), 1952. NATO,. NATO . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Host Nation Support (HNS) Memorandum of Understanding, NATO Standardization Agreemen. NATO . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- M.E. Villiger. Preliminary Material; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 505-535, 919-977.

- Fikentscher, Wolfgang; Heinemann, Andreas. Schuldrecht: Allgemeiner und Besonderer Teil (De Gruyter Studium) ; Fikentscher, Wolfgang; Heinemann, Andreas, Eds.; De Gruyter: Germany , 2017; pp. § 6, Abs.5.

- Heinrich Honsell. Schweizerisches Obligationenrecht. Besonderer Teil: 10., ergänzte und verbesserte Auflage (Stämpflis juristische Lehrbücher); Stämpfli Verlag: Switzerland , 2017; pp. 4. Teil, Kapitel 3.

- Peter Bydlinski:. Allgemeiner Teil des Bürgerlichen Rechts.; Peter Bydlinski, Peter Apathy, Ferdinand Kerschner, Eds.; Springer: Germany , 2017; pp. 321-354.

- stian Grüneberg (Hrsg.): Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch – Kommentar. 83. Auflage, Beck. CH Beck . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch: BGB. CH Beck . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Kurzkommentar zum ABGB. Springer Nature. Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Obligationenrecht : Allgemeiner Teil. Alexandria . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Konkludenter Vertragsschluss: Was ist konkludentes Handeln?. Jura Forum . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Grüneberg-Kommentar zum BGB mit Nebengesetzen. Lehmanns . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- UCC § 1‑303 (Course of Performance, Course of Dealing, Usage of Trade).. Cornell law School . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Christina Binder; Mark Eugen Villiger, Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Leiden and Boston, 2009, ISBN 9789004168046, xxxiv + 1058 pp., EUR 240.00. Austrian Rev. Int. Eur. Law Online. 2013, 15, 522-524.

- Tim Staal; Duncan B. Hollis (ed.). The Oxford Guide To Treaties. Eur. J. Int. Law. 2013, 24, 1239-1244.

- United Nations: Final Clauses of Multilateral Treaties Handbook. UN Publications, 2003. United Nations . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Jan Klabbers. International Law; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2020; pp. 223-276.

- Robert E. Dalton; The Vienna Conventions on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary. Edited by Olivier Corten and Pierre Klein. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. 2 vols. Pp. lxxxiii, 2071. Index. $750.. Am. J. Int. Law. 2012, 106, 898-903.

- John Dugard; O. Corten and P. Klein, eds., The Vienna Conventions on the Law of Treaties. A Commentary, 2 vols., Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011, 2071 pp., ISBN 978-0-19-957352-3.. Neth. Int. Law Rev.. 2012, 59, 303-307.

- Klein Corten. The Vienna Conventions on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2011; pp. 232-255.

- Summary of Practice of the Secretary-General as Depositary of Multilateral Treaties, UN Office of Legal Affairs, U.N. Doc. ST/LEG/7/Rev.1. United Nations . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Alexandru Bolintineanu; Expression of Consent to be Bound by a Treaty in the Light of the 1969 Vienna Convention. Am. J. Int. Law. 1974, 68, 672-686.

- The Multilateral Treaty Amendment Process: A Case Study M. J. Bowman. JSTOR. Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Hugh Thirlway: The Sources of International Law. Oxford University Press, 2014. Pageplace. Retrieved 2026-1-9

- International Court of Justice: North Sea Continental Shelf Cases (1969), ICJ Reports 1969, S. International Court of Justice . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Mark Eugen Villiger. Customary International Law and Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 1985; pp. 86-112.

- Bin Cheng: General Principles of Law as Applied by International Courts and Tribunals. Cambridge University Press, 2006,. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Mortimer N. S. Sellers. The Sources of International Law; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, United States, 2006; pp. 38-45.

- Ademola Abass. Sources of international law; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2011; pp. 25-66.

- Wm. W. Bishop. Sources of international law; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 214-250.

- W. Friedmann; Bin Cheng; General Principles of Law as Applied by International Courts and Tribunals. Int. Journal: Canada's J. Glob. Policy Anal.. 1955, 10, 323-344.

- Bing C. Book Review: General Principles of Law as Applied by International Courts and Tribunals.. David Davies Mem. Inst. Int. Stud. Annu. Mem. Lect.. 1957, 1, 71-71.

- Arthur Watts. The International Court and the Continuing Customary International Law of Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 251-266.

- Mark Eugen Villiger. Customary International Law and Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 1985; pp. 121-166.

- United Nations: Treaty Handbook. UN Publications, 2020. United Nations . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- United Nations Office of Legal Affairs: Summary of Practice of the Secretary‑General as Depositary of Multilateral Treaties. UN Publications, 1994. United Nations . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- Anthony Aust. Modern Treaty Law and Practice; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2007; pp. 323-376.

- Oliver Dörr; Kirsten Schmalenbach. Article 76. Depositaries of treaties; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, United States, 2011; pp. 1297-1307.

- M.E. Villiger. Article 76: Depositaries Of Treaties; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 919-933.

- NATO: Agreement between the Parties to the North Atlantic Treaty regarding the Status of their Forces (SOFA), 1951. NATO . Retrieved 2026-1-9

- J. Klabbers; Anthony Aust, Modern Treaty Law and Practice. Nord. J. Int. Law. 2002, 71, 203-205.

- Malgosia Fitzmaurice; Modern Treaty Law and Practice. By A Aust [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. xxvi + 442pp. ISBN 052159846X. £29.95.]. Int. Comp. Law Q.. 2003, 52, 539-539.

- Norman S. Marsh; The Law of Treaties. Int. Aff.. 1962, 38, 396-397.

- Donald R. Rothwell; Stuart Kaye; Afshin Akhtarkhavari; Ruth Davis. Law of treaties; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2010; pp. 102-158.

- Norman S. Marsh; The Law of Treaties. Int. Aff.. 1962, 38, 396-397.

- Donald R. Rothwell; Stuart Kaye; Afshin Akhtarkhavari; Ruth Davis. Law of treaties; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2010; pp. 102-158.