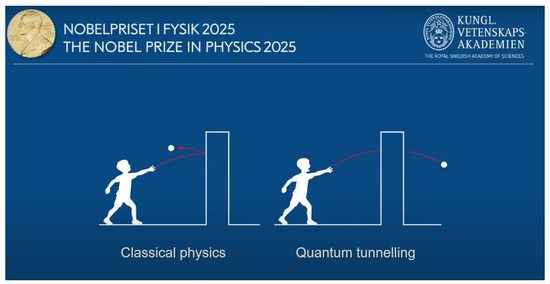

This report bridges fundamental ideas from introductory calculus to advanced concepts in quantum mechanics and nonlinear dynamics. Beginning with the behavior of second derivatives in oscillatory and exponential functions, it introduces the Airy equation and the WKB approximation as mathematical tools for describing wave propagation and quantum tunneling near turning points—locations where transitions between oscillatory and exponential components occur. The analysis then extends to the non-dissipative Lorenz model, whose double-well potential and solitary-wave (sech-type) solutions reveal a deep mathematical connection with the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Together, these examples highlight the universality of second-order differential equations in describing turning-point dynamics, encompassing physical phenomena ranging from quantum tunneling to coherent solitary-wave structures in fluid and atmospheric systems.

- quantum tunneling

- turning points

- quantum mechanics

- nonlinear dynamics

- solitary waves

- propagating waves

- evanescent waves

- the Airy equation

- the Schrödinger equation

- the non-dissipative Lorenz model

and Bi solutions of the Airy equation are presented, followed by an introduction to the WKB approximation. Section 4 discusses the non-dissipative Lorenz model, identifies two turning points in its structure, and establishes its relationship with the amplitude equation of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLS). A summary is provided at the end. Appendix A and Appendix B offer additional details on the analysis of phase and amplitude in the nonlinear and linear Schrödinger equations, respectively. Appendix C offers a concise overview of the non-dissipative Lorenz model. Appendix D discusses effective turning points of the non-dissipative Lorenz model.

References

- Caldeira, A.O.; Leggett, A.J. Influence of Dissipation on Quantum Tunneling in Macroscopic Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 46, 211–214.

- Clarke, J.; Cleland, A.N.; Devoret, M.H.; Esteve, D.; Martinis, J.M. Quantum Mechanics of a Macroscopic Variable: The Phase Difference of a Josephson Junction. Science 1988, 239, 992–997.

- Devoret, M.H.; Martinis, J.M.; Clarke, J. Measurement of Macroscopic Quantum Tunneling out of a Zero-Voltage State of a Current-Biased Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985, 55, 1908–1911.

- Gunn, J.B. The 1973 Nobel Prize for physics. Proc. IEEE 1974, 62, 823–824.

- Martinis, J.M.; Devoret, M.H.; Clarke, J. Energy-Level Quantization in the Zero-Voltage State of a Current-Biased Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985, 55, 1543–1546.

- The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025—Popular Information. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2025/popular-information/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025—Popular Information. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2025/10/press-physicsprize2025-figure2.jpg (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Voss, R.F.; Webb, R.A. Macroscopic Quantum Tunneling in 1-µm Nb Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 47, 265–268.

- Bethe, H.A. Energy Production in Stars. Phys. Rev. 1939, 55, 103–147.

- Gamow, G. Zur Quantentheorie des Atomkernes. Z. Für Phys. 1928, 51, 204–212.

- Nobel Foundation. The Nobel Prize in Physics 1973. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1973/summary (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Binnig, G.; Rohrer, H. Scanning Tunneling Microscopy—From Birth to Adolescence. 1987. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/binnig-lecture.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986. 1986. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1986/summary (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Bender, C.M.; Orszag, S.A. Advanced Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers: Asymptotic Methods and Perturbation Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999.

- Dunster, T.M. Simplified Airy function asymptotic expansions for reverse generalised Bessel polynomials. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20934.

- Brillouin, L. La mécanique ondulatoire de Schrödinger: Une méthode générale de resolution par approximations successives. Comptes Rendus L’AcadéMie Sci. 1926, 183, 24–26.

- Gill, A.E. Atmosphere–Ocean Dynamics, 1st ed.; International Geophysics Series; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; Volume 30.

- Green, G. On the motion of waves in a variable canal of small depth and width. Trans. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1837, 6, 457–462.

- Kramers, H.A. Wellenmechanik und halbzahlige Quantisierung. Z. Für Phys. 1926, 39, 828–840.

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory, 3rd ed.; Course of Theoretical Physics; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1977; Volume 3.

- Liouville, J. Sur le développement des fonctions et séries. J. Mathématiques Pures Appliquées 1837, 1, 16–35.

- Mathews, J.; Walker, R.L. Mathematical Methods of Physics, 2nd ed.; Addison–Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1970.

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017.

- Wentzel, G. Eine Verallgemeinerung der Quantenbedingungen für die Zwecke der Wellenmechanik. Z. Für Phys. 1926, 38, 518–529.

- Haberman, R. Applied Partial Differential Equations with Fourier Series and Boundary Value Problems, 5th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2013; p. 756.

- Shen, B.-W. Homoclinic Orbits and Solitary Waves within the Non-dissipative Lorenz Model and KdV Equation. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2020, 30, 2050257.