This report bridges fundamental ideas from introductory calculus to advanced concepts in quantum mechanics and nonlinear dynamics. Beginning with the behavior of second derivatives in oscillatory and exponential functions, it introduces the Airy equation and the WKB approximation as mathematical tools for describing wave propagation and quantum tunneling near turning points—locations where transitions between oscillatory and exponential components occur. The analysis then extends to the non-dissipative Lorenz model, whose double-well potential and solitary-wave (sech-type) solutions reveal a deep mathematical connection with the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Together, these examples highlight the universality of second-order differential equations in describing turning-point dynamics, encompassing physical phenomena ranging from quantum tunneling to coherent solitary-wave structures in fluid and atmospheric systems.

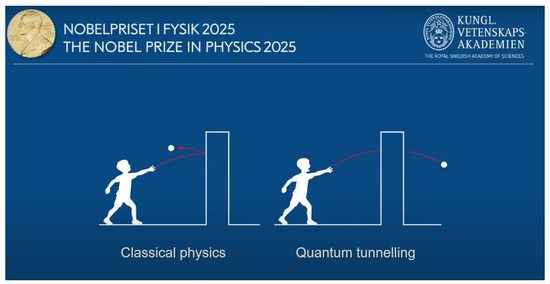

In 2025, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for pioneering research related to the phenomenon of quantum tunneling

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] (see

Figure 1). Quantum tunneling describes how particles can traverse potential barriers that would be classically forbidden—a process central to nuclear fusion in stars

[9][10][9,10], semiconductor devices

[11], and scanning tunneling microscopy

[12][13][12,13]. This remarkable discovery not only deepened our understanding of quantum mechanics but also inspired new perspectives on wave propagation and energy transfer across different physical systems.

Figure 1 highlights the scientific importance of this concept.

Figure 1. Quantum tunneling. The illustration is adapted from the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics press material, awarded for pioneering work on quantum tunneling, and is reproduced with permission. Credit: © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

[7].

Originally derived from the Schrödinger equation, the phenomenon of tunneling can be described mathematically through the Airy equation

[14][15][14,15] and the WKB (Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin) approximation (

[14][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]). These methods reveal how an oscillatory (propagating) solution transitions smoothly into an exponentially decaying (evanescent) solution near a turning point. The Airy equation provides a local model valid near the turning point, while the WKB method offers an asymptotic description of the same wave behavior away from it.

Beyond quantum mechanics, the same mathematical structures emerge in nonlinear systems. The nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation (

[25]) and the non-dissipative Lorenz model (

[26]) share strikingly similar amplitude equations that govern solitary waves and homoclinic orbits. This correspondence demonstrates the beauty of mathematical universality: the same second-order nonlinear differential forms that describe quantum tunneling also govern coherent wave structures in fluid dynamics and atmospheric models.

This report, therefore, explores how fundamental second-order differential equations connect seemingly different phenomena—the propagation of waves, quantum tunneling, and nonlinear solitary waves. Beginning from elementary calculus concepts, we trace a logical path from simple oscillations to complex nonlinear dynamics represented by the non-dissipative Lorenz model. The goals are twofold: (1) to help students who have completed Calculus I and II visualize the mathematical meaning of turning points and transitions between oscillatory and exponential behaviors, and (2) to show how similar mathematical structures appear across quantum mechanics, wave theory, and nonlinear dynamics.

This report is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the properties of second derivatives of the sine, cosine, and exponential functions to help first-year college students who have completed Calculus I and II understand the concepts of propagating and evanescent modes. Building on these introductory ideas,

Section 3 demonstrates how a local analysis of the linear Schrödinger equation leads to the Airy equation, which contains a turning point where a transition between oscillatory and exponential components occurs. The corresponding

Aiand Bi solutions of the Airy equation are presented, followed by an introduction to the WKB approximation. Section 4 discusses the non-dissipative Lorenz model, identifies two turning points in its structure, and establishes its relationship with the amplitude equation of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLS). A summary is provided at the end. Appendix A and Appendix B offer additional details on the analysis of phase and amplitude in the nonlinear and linear Schrödinger equations, respectively. Appendix C offers a concise overview of the non-dissipative Lorenz model. Appendix D discusses effective turning points of the non-dissipative Lorenz model.