ElThis estudio aborda la incorporación conjunta de Bstudy evaluated the influence of adding biochar y laand the bacteria Bacillus subtilis coumo aditivos sostenibles para mejorar las propiedades físico-mecánicas delBacillus subtilis on the physical and mechanical properties of concreto estructural, contribuyendo al desarrollo de materiales más ecológicos y resistentes. La investigación ofrece un enfoque innovador en la bioingeniería del concreto, alineado con los objetivose designed for a compressive strength of f’c = 280 kg/cm² in Chiclayo, aiming to improve its performance and promote sustainable construcción sostenible (ODS)tion practices in line with SDG 9.

La impCortancia de este trabajo radica en demostrar experimentalmente cual es la óptima ncrete mixes were prepared with four combinación de Btions of biochar y Bacillus subtilis, que trasnd el desarrollo de la investigación se determinó que 2 % de Biochar y 4.5 % dBacillus subtilis (C1, C2, C3, C4). The Bacillus subtilis mejorva la resistencia a compresión, tracción y flexión sinluated properties included physical characteristics as well as comprometer la trabajabilidad del concreto. Además, se complementa con un análisis estructural en ETABS, evidenciando que el concreto modificado presenta mayor rigidez y uessive, flexural, and tensile strength. Results showed that the mix containing 2% biochar and 4.50% Bacillus subtilis exhibited the best performance, with increases of 4.54% in comportamiento sísmico más favorable que el concreto convencional.

Estosressive strength, 6.72% in tensile strength, and 51.70% in hafllazgos amplían los resultados reportados por Suárez, Sánchez y Vera (2023) y Zhou et al. (2023), quexural strength, attributed to the combienes exploraron el papel del Bd effect of biochar como as a microrelleno, y por Huaynalaya Rashuaman et al. (2024) y Fernández (2024), que estudiaron el efecto biocementante defiller and the bacterium as a biocementing agent. Furthermore, in the modeling of an eight-story building, the experimental concrete demonstrated better structural Bacillus subtilis.performance Pcor lo tanto, la presente investigación integra ambos enfoques en un solo modelo experimental, aportando nueva evidencia científica sobre la sinergia entre materiales carbonosos y agentes biológicos en el concreto empared to the control, meeting the drift limits established in E.030. These findings indicate that the combined addition of both materials improves density, strength, and linear seismic performance of concrete, positioning it as an innovative and sustainable alternative for the development of more resilient infrastructurale.

- Bacterias

- Nutrition

- microorganisms

- structural desing

- structural element

- earthquake

- technology

Research Article

1. Introduction

Evaluation of the Influence of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis Addition on the Physicomechanical Properties of Concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm² – Chiclayo, 2025

Angie B. Raico Caro¹*, Jeisús S. Yampufé Guevara¹, Julio C. Benites Cherone o2

|

Academic Editor: Firstname Lastname Received: date Revised: date Accepted: date Published: date Citation: To be added by editorial staff during production. Copyright: © 2025 by the authors. Submitted for possible open access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). |

1 Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture, César Vallejo University, Chiclayo 14012, Peru;he anraicoc@ucvvirtual.edu.pe; jyampufe@ucvvirtual.edu.pe

2 César Vallejo University; jbenitesce@ucvvirtual.edu

* Correspondence: anraicoc@ucvvirtual.edu.pe; A.R Tel.: +51 959390712; J.Y Tel.: +51 946 452 975

Abstract

This study evaluated the influence of adding biochar and the bacterium Bacillus subtilis on the physical and mechanical properties of concrete designed for a compressive strength of f’c = 280 kg/cm² in Chiclayo, aiming to improve its performance and promote sustainable construction practices in line with SDG 9. Concrete mixes were prepared with four combinations of biochar and Bacillus subtilis (C1, C2, C3, C4). The evaluated properties included physical characteristics as well as compressive, flexural, and tensile strength. Results showed that the mix containing 2% biochar and 4.50% Bacillus subtilis exhibited the best performance, with increases of 4.54% in compressive strength, 6.72% in tensile strength, and 51.70% in flexural strength, attributed to the combined effect of biochar as a microfiller and the bacterium as a biocementing agent. Furthermore, in the modeling of an eight-story building, the experimental concrete demonstrated better structural performance compared to the control, meeting the drift limits established in E.030. These findings indicate that the combined addition of both materials improves density, strength, and linear seismic performance of concrete, positioning it as an innovative and sustainable alternative for the development of more resilient infrastructure.

Keywords: Bacteria, Nutrition, Microorganisms, Structural Design, Structural Element, Earthquake, Technology, Structural Framest widely used construction materials work

1. Introduction

Concrete is one of the most widely used construction materials worldwwide, and its mechanical and physical performance is fundamental for structural safety and sustainability. However, traditional concrete has limitations, such as the formation of microcracks. In this regard, it has been observed that one of the main causes of structural failures is poor construction practices, which can be avoided. According to [1] , these failures are attributed to internal factors such as unskilled labor, poorly proportioned mix designs, and even the use of aggregates that do not meet required standards.

Worth noting that in the early stages, these issues do not generate evident damage, but when the structure is subjected to significant loads, the problem worsens. On the other hand, [2] highlight the influence of external factors arising environment, such as climatic conditions and ambient humidity. As a consequence, [3] indicates that crack formation negatively affects the service life of structures. They also point out that such failures result combined effect of internal and external factors that compromise the behavior of concrete, leading to a decrease in its physical and mechanical properties.

This issue has become more critical with the occurrence of structural failures. For example, a report by [4] states that excessive rainfall nationwide has caused structural failures affecting and collapsing 217 bridges. Additionally, [5] reported that approximately 16.2 % of schools are at risk of collapse. Likewise, the [6] reported that 97 % of healthcare facilities present inadequate infrastructure.

For these reasons, this study evaluates the influence of adding biochar and Bacillus subtilis on the physicomechanical properties of concrete with a design strength of f’c = 280 kg/cm². This research addresses an area with limited theoretical background regarding the combined incorporation of these two additives in medium-strength concrete, as classified under Chapter V of the Peruvian Technical Standard E.060, commonly used for structures of intermediate complexity.

2. Materials and Methods

Ordinary Portland Cement Type I, commercially available in the local market, was used as the main binder. The fine aggregate was obtained La Victoria–Pátapo quarry and had a fineness modulus of 2.92, while the coarse aggregate was sourced Pacherrez–Pucalá quarry and had a nominal maximum size of 3/4 inch. The concrete mixture was prepared with potable water, maintaining a water–cement (w/c) ratio of 0.55.

The biochar used in this study was produced from organic waste such as weeds and dry and wet pruning branches. It was incorporated into the concrete mix at different percentages by weight of cement as follows:

- C1: 2% Biochar + 4.5% Bacillus subtilis

- C2: 2.5% Biochar + 6.5% Bacillus subtilis

- C3: 3% Biochar + 7.5% Bacillus subtilis

- C4: 3.5% Biochar + 9.5% Bacillus subtilis

The bacterial strain used was Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii ATCC® 6633™ / WDCM 00003. Two culture media were employed: Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) and MYP (mannitol, egg yolk, and agar with polymyxin). The reactivation process began by inoculating the strain on Petri dishes containing both media. TSA served as a nutrient-rich medium to promote microbial growth, while MYP was used to verify purity and morphological characteristics. After inoculation, the plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 hours, producing visible colonies of Bacillus subtilis.

Subsequently, 5 mL of the culture were transferred into 42 tubes containing Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth and were reincubated at 30 °C for 24 hours. The bacterial concentration was determined using the McFarland nephelometric method, adjusting the turbidity to 0.93 MCF, which corresponded to approximately 2.8 × 10⁸ cells/mL. The bacterial suspension was diluted in 3 mL of sterile physiological saline solution (1:3 ratio) and was homogenized using a vortex mixer.

A total of 42 BHI broth tubes were scaled up to 42 flasks of 500 mL each, reaching a final culture volume of 21 liters. These flasks were incubated at 30 °C for 18 hours to obtain the bacterial solution used in the experimental concrete mixtures.

2.2. Experimental Design

2.1. Experimental Design

The experimental program consisted of a control mixture (f’c = 280 kg/cm²) and four test mixtures containing biochar and Bacillus subtilis in different proportions. A total of 150 cylindrical specimens (10 × 20 cm) were prepared for compressive and splitting tensile strength tests, distributed as five specimens per mixture and per testing age (7, 14, and 28 days).

In addition, 45 prismatic beams (15 × 15 × 45 cm) were produced for flexural strength tests, with three specimens for each curing age.

2.3. Testing Procedures

2.2. Testing Procedures

Concrete properties were evaluated in accordance with the Peruvian Technical Standards (NTP) established by INACAL. The following standardized tests were conducted:

- Slump test (workability): NTP 339.035 – “Slump of Concrete.”

- Unit weight: NTP 339.046 – “Unit Weight of Concrete.”

- Temperature of fresh concrete: NTP 339.184 – “Temperature of Concrete.”

- Splitting tensile strength: NTP 339.084 – “Tensile Strength.”

- Compressive strength: NTP 339.034 – “Compressive Strength.”

- Flexural strength: NTP 339.078 – “Flexural Strength.”

All tests were performed at 7, 14, and 28 days of curing under controlled laboratory conditions. Each specimen was labeled, tested, and recorded following the procedures specified in the respective NTP standards.

3. Results

3.1. Biochar Characterization

The characterization of the biochar is carried out to verify its suitability as an additive for structural concrete with a design strength of f’c = 280 kg/cm². The material is obtained through open pyrolysis of plant residues such as branches, prunings, and weeds, until a stable and homogeneous product is achieved. The results after the process show that from 20–25 kg of biomass, approximately 10 kg of biochar are obtained in 3 hours. This duration may vary depending on the type and hardness of the material. The process reaches a calcination degree of 500 °C at the beginning of the pyrolysis and is controlled to reach a temperature of 700 °C, parameters that are sufficient to generate a biochar with adequate porosity and stability for use in concrete mixtures.

After the material preparation process, the biochar is manually ground and sieved to achieve a fine and homogeneous granulometry. Then dried at 100 °C for 24 hours to eliminate residual moisture that could affect the dosage and setting of the concrete. Finally, a particle size analysis is performed according to NTP 400.012. The results show that the calcination degree allows obtaining a material with controlled porous structure. Likewise, the granulometric curves and the test performed according to the applicable standard confirm a size distribution that favors its incorporation into the concrete matrix without requiring special additives to stabilize the mixture in the tested proportions.

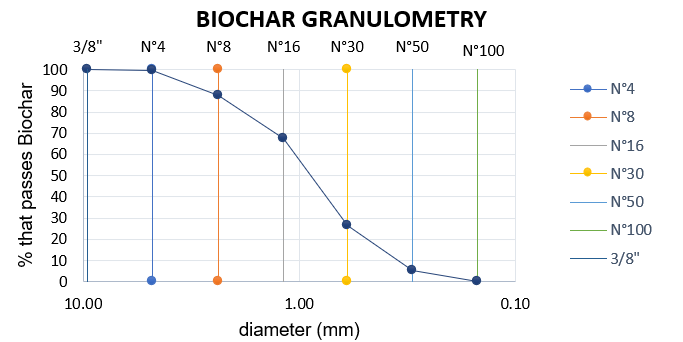

Below is a summary of the most relevant characterization parameters obtained after the pyrolysis process and laboratory analysis, shown in TableTable 1 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1. Summary of Biochar Characterization Parameters Used in the Research

Summary of Biochar Characterization Parameters Used in the Research.

|

Evaluated Parameter |

Result |

|---|---|

|

Raw material (initial mass) |

20–25 kg |

|

Biochar yield |

10 kg |

|

Pyrolysis duration |

3 h |

|

Calcination temperature |

700 °C |

|

Post-drying |

100 °C for 24 h |

|

Grinding treatment |

Manual grinding to fine particle size |

|

Biochar granulometry |

0.3–0.4 mm |

|

Evaluated Parameter |

Result |

|---|---|

|

Raw material (initial mass) |

20–25 kg |

|

Biochar yield |

10 kg |

|

Pyrolysis duration |

3 h |

|

Calcination temperature |

700 °C |

|

Post-drying |

100 °C for 24 h |

|

Grinding treatment |

Manual grinding to fine particle size |

|

Biochar granulometry |

0.3–0.4 mm |

Figure 1. Biochar granulometric curve

Biochar granulometric curve.

3.2. Cultivation and Encapsulation of Bacillus subtilis

The bacterial culture is carried out in order to obtain an active and viable strain of Bacillus subtilis for its incorporation into concrete. The strain is selected for its resistance to alkaline conditions and its ability to induce calcium carbonate precipitation in cementitious media. The cultivation process comprises four main stages: preparation of the culture medium, inoculation, incubation, and bacterial encapsulation.

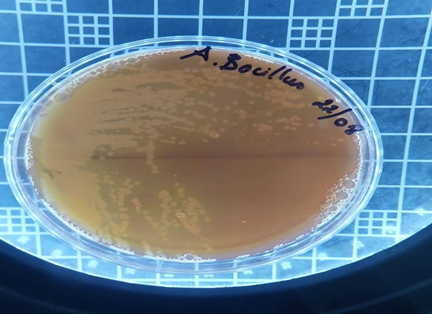

Figure 2. Colonies of Bacillus subtilis under microscope.

In the first stage, the BHI (Brain Heart Infusion) medium is prepared under controlled conditions. Then, inoculation is performed on TSA (Tryptic Soy Agar), where rounded, smooth, and opaque colonies characteristic of Bacillus subtilis are observed, as shown in Figure 2. Subsequently, a second liquid inoculation is carried out in BHI, which is incubated at 30 °C for 18 h until reaching turbidity equivalent to the McFarland 0.5–1.0 standard, corresponding to an approximate concentration of 2.8 × 10⁸ cel/ml.

Figure 2. Colonies of Bacillus subtilis under microscope

The bacterial concentration is verified through nephelometric measurements and visual comparison with the McFarland standards. The readings show uniformity among repetitions, ensuring culture homogeneity before encapsulation.

In the final stage, the bacteria are encapsulated in expanded clay with a particle size of 3–8 mm and expanded perlite of 0–3 mm. These materials containing particulate matter, such as the clay, are previously washed, then both are dried to remove any residual moisture and are sterilized to preserve the controlled environment where the bacteria will remain. Both materials serve as porous supports to host Bacillus subtilis and protect it during mixing with cement. To enhance the survival of bacterial activity, the mixture is supplemented with a calcium lactate and dextrose solution in proportions of 2 % and 1 % of dry weight, respectively.

During encapsulation, the porous particles are immersed in the bacterial solution for 24 h to ensure complete absorption. This procedure allows maintaining the integrity of the bacteria, ensuring their activation in the presence of moisture and oxygen during the concrete setting process.

3.3. Determination of the Optimal Addition Percentage of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis

To establish the optimal dosage of the additives, experimental mixtures are prepared with different combined proportions of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis (C1, C2, C3, and C4), relative to the weight of cement. These combinations are compared with a control mix without additives.

The samples are subjected to slump, unit weight, temperature, and mechanical strength tests such as compression, tension, and flexion, following the Peruvian Technical Standards NTP 339.035, 339.046, 339.184, 339.034, 339.084, and 339.078, respectively.

The values obtained for the properties in the fresh state show that the combinations with higher Biochar content slightly reduce the fluidity of the concrete due to its high porosity and absorption; however, this effect is compensated by the bacterial action, which increases the cohesion of the mix. The results show that the dosage of 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis achieves a slump similar to the control mix, maintains an adequate density, and keeps a controlled temperature, conditions that favor uniform setting.

In the mechanical strength tests, the same combination records the highest increase in concrete strength at 28 days of curing, with an improvement of 4.54% in compression, 6.72% in tension, and 51.70% in flexion compared to the control concrete. These results are due to the synergistic effect between both additives: Biochar acts as a micro-filler, reducing porosity, while Bacillus subtilis promotes the precipitation of calcite crystals, sealing microcracks and reinforcing the concrete matrix.

In general, the combination of 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis is the most efficient in improving the physical–mechanical performance of concrete, as shown in Table 2. This mixture maintains the workability of the concrete, improves compactness, and significantly increases flexural strength, confirming its selection as the optimal dosage for the seismic analysis of a building as a test model.

Table 2. Summary of Physical and Mechanical Test Results for Control and Experimental Concrete

Summary of Physical and Mechanical Test Results for Control and Experimental Concrete.

|

Property Evaluated |

Control |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Slump (cm) |

10.16 |

9.91 |

9.40 |

9.14 |

7.84 |

|

Unit Weight (kg/m³) |

2387 |

2379 |

2373 |

2367 |

2360 |

|

Temperature (°C) |

26 |

27 |

28 |

28 |

29 |

|

Compressive Strength (kg/cm2, 28 días) |

299.4 |

313 |

290.6 |

279 |

273.6 |

|

Tensile Strength (kg/cm2, 28 días) |

26.8 |

28.6 |

26.8 |

26.8 |

24.8 |

|

Tensile Strength (kg/cm2, 28 días) |

32.3 |

49 |

46 |

44.3 |

38 |

3.4 Physical Properties of Concrete

3.4. Physical Properties of Concrete

3.4.1 Concrete Slump

3.4.1. Concrete Slump

The slump test shows variations directly related to the materials added to the mix. The control concrete presents a plastic slump of 10.16 cm; however, with the progressive incorporation of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis, a gradual decrease in slump is observed, reaching a minimum value of 7.84 cm in the mix with 3.50% Biochar and 9.50% Bacillus subtilis, representing a reduction of approximately 22.80% compared to the control concrete.

This trend indicates that the workability of the concrete decreases as the content of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis increases, as shown in Table 3. Despite this reduction, the values obtained remain within the plastic range of 7.62–10.16 cm, according to NTP 300.035, ensuring adequate consistency for the mechanical tests conducted in this research.

Table 3. Results of Concrete Slump Test

Results of Concrete Slump Test.

|

Sample |

Slump (cm) |

|---|---|

|

Control |

10.16 |

|

C1 |

9.91 |

|

C2 |

9.4 |

|

C3 |

9.14 |

|

C4 |

7.84 |

3.4.2 Concrete Unit Weight

According to NTP 339.046 (2020), normal-weight concrete must present a unit weight between 1842 and 2483 kg/m³, while the corresponding slump test should fall within the range of 7.5 to 15 cm, ensuring a workable and adequately compacted mixture.

As shown in Table 4, the control concrete achieved a unit weight of 2387 kg/m³, which falls within the range established by the standard, confirming good compaction and homogeneity. With the progressive incorporation of Biochar and *Bacillus subtilis*, a slight decrease in unit weight is observed, reaching values of 2379, 2373, 2367, and 2360 kg/m³ as the amount of additives increased, with the mix containing 3.5% Biochar and 9.5% *Bacillus subtilis* showing the lowest value.

This gradual reduction represents approximately 1.1% less than the control concrete, which can be attributed to the lightweight and porous nature of Biochar, as well as to bacterial activity during mixing. However, the obtained values remain within the normative range, indicating that the modified mixtures maintain an adequate unit weight without negatively affecting the density or quality of the fresh concrete.

Table 4. Results of the unit weight test of concrete

Results of the unit weight test of concrete.

|

Sample |

Unit Weight (kg/m³) |

|---|---|

|

Control |

2387 |

|

C1 |

2379 |

|

C2 |

2373 |

|

C3 |

2367 |

|

C4 |

2360 |

3.4.3 Concrete Temperature

3.4.3. Concrete Temperature

As shown in Table 5, the control concrete recorded a temperature of 26°C, while the mixes incorporating Biochar and *Bacillus subtilis* presented temperatures of 27, 28, and 29°C. These results fall within the range established by ACI 305R-99, which recommends that the temperature of fresh concrete should remain between 20°C and 30°C. This indicates that the evaluated mixtures maintained suitable thermal conditions during their preparation, allowing for faster setting and an acceleration in early strength development without exceeding the limits that could compromise workability or material durability.

Table 5. Results of the unit weight test of concrete

Results of the unit weight test of concrete.

|

Sample |

Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|

|

Control |

26 |

|

C1 |

27 |

|

C2 |

28 |

|

C3 |

28 |

|

C4 |

29 |

3.5 Mechanical Properties of Concrete

3.5. Mechanical Properties of Concrete

3.5.1 Compressive Strength

The results presented in Table 6 show that at 28 days of curing, the experimental concrete with 2% Biochar and 4.50% Bacillus subtilis reaches the highest average strength, with a value of 313.00 kg/cm², while the control concrete reaches 299.40 kg/cm², representing an improvement of 4.50%.

This behavior remains consistent at 7 and 14 days, confirming that the moderate incorporation of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis contributes to the progressive development of strength and material durability.

In contrast, mixtures with higher percentages show a decrease in strength, suggesting that excess Biochar generates low-density zones and reduces the bond between the cement paste and aggregates.

Therefore, determined that the optimal dosage corresponds to 2% Biochar and 4.50% Bacillus subtilis, as it provides the best mechanical performance in compression.

273.6 |

Table 6. Results of the concrete compressive strength test.

Table 6. Results of the concrete compressive strength test

|

Sample |

7 days |

14 days |

28 days |

|---|---|---|---|

|

kg/cm2 |

|||

|

Control |

177.4 |

230.2 |

299.4 |

|

C1 |

183.6 |

243.6 |

313 |

|

C2 |

168 |

225 |

290.6 |

|

C3 |

159.2 |

213.4 |

279 |

|

C4 |

152.6 |

205.2 |

273.6 |

3.5.2 Splitting Tensile Strength

According to the results in Table 7, the concrete with 2% Biochar and 4.50% Bacillus subtilis reaches the highest splitting tensile strength at 28 days, with an average of 28.60 kg/cm², surpassing the control concrete (26.80 kg/cm²) by 6.70%.

This trend also appears at earlier ages, demonstrating the effectiveness of this combination in improving the internal cohesion and tensile capacity of the concrete.

The increase relates to the mineralization induced by bacterial activity and the greater densification of the cement matrix, due to the action of Biochar as a micro-filler. On the other hand, mixtures with higher proportions do not show significant improvements, indicating that the efficiency depends on a controlled and balanced dosage of the additives.

Table 7. Results of the concrete tensile strength test

Table 7. Results of the concrete tensile strength test.

|

Sample |

7 days |

14 days |

28 days |

|---|---|---|---|

|

kg/cm2 |

|||

|

Control |

20.4 |

22.4 |

26.8 |

|

C1 |

20.8 |

23.8 |

28.6 |

|

C2 |

19.6 |

21.6 |

26.8 |

|

C3 |

17.4 |

19.8 |

26.8 |

|

C4 |

16.8 |

19.4 |

24.8 |

|

Sample |

7 days |

14 days |

28 days |

|

kg/cm2 |

|||

|

Control |

177.4 |

230.2 |

299.4 |

|

C1 |

183.6 |

243.6 |

313 |

|

C2 |

168 |

225 |

290.6 |

|

C3 |

159.2 |

213.4 |

279 |

|

C4 |

152.6 |

205.2 |

|

3.5.3 Flexural Strength

Regarding flexural strength, the results presented in Table 8 indicate that the mixture with 2% biochar and 4.50% Bacillus subtilis reaches an average value of 49.0 kg/cm², compared to 32.3 kg/cm² for the control concrete, representing an increase of 51.6%.

This increase confirms the synergistic effectiveness between both components, which promote the structural integrity of the material through better stress distribution and reduced microcracking.

In addition, the combined action of Biochar and bacteria maintains and even enhances its effect over time, showing a process of self-healing and progressive densification of the cement matrix.

Table 8. Results of the concrete flexural Strength test

Table 8. Results of the concrete flexural Strength test.

|

Sample |

7 days |

14 days |

28 days |

|---|---|---|---|

|

kg/cm2 |

|||

|

Control |

22.7 |

28 |

32.3 |

|

C1 |

38 |

46 |

49 |

|

C2 |

28.7 |

42 |

46 |

|

C3 |

28.7 |

39.3 |

44.3 |

|

C4 |

27.7 |

35.7 |

38 |

3.6 Flexural Strength

3.6.2 Vibration Periods

The modal analysis shows a decrease in the fundamental periods in the model with modified concrete. The first vibration mode decreases from 0.535 s (control) to 0.529 s (modified), while the second and third modes show smaller reductions, maintaining a similar mass distribution, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Results of vibration periods in modeling with pattern and experimental concrete in ETABS 21 software

Table 9. Results of vibration periods in modeling with pattern and experimental concrete in ETABS 21 software.

|

Mode |

Control [s] |

C1 [s] |

Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

0.535 |

0.529 |

-1.12 |

|

2 |

0.473 |

0.468 |

-1.06 |

|

3 |

0.454 |

0.449 |

-1.10 |

This reduction in periods indicates an increase in the overall stiffness of the structural system, showing that the experimental concrete responds with lower deformability under equivalent static loads. This behavior relates to the physical and mechanical improvements of the material, especially the greater compactness and internal adhesion generated by the interaction between Biochar and Bacillus subtilis, which contributes to a more stable performance under seismic actions.

In addition, the percentage of vibration modes shows a slight decrease in the participation of modes in the X and Z directions, suggesting a more balanced redistribution of structural stiffness and a greater capacity of the system to dissipate seismic energy uniformly, as shown in Table 10.

Table 10. Results of vibration modes in modeling with pattern and experimental concrete in ETABS 21 software

Table 10. Results of vibration modes in modeling with pattern and experimental concrete in ETABS 21 software.

|

RESULTS OF PATTERN CONCRETE |

|||||

|

Case |

Mode |

Period |

UX |

UY |

RZ |

|

Modal |

1= Y |

0.535 |

0.21% |

57.05% |

15.97% |

|

Modal |

2= X |

0.473 |

39.77% |

8.59% |

23.24% |

|

Modal |

3 = Z |

0.454 |

31.70% |

7.18% |

32.96% |

|

EXPERIMENTAL CONCRETE RESULTS |

|||||

|

Case |

Mode |

Period |

UX |

UY |

RZ |

|

Modal |

1= Y |

0.529 |

0.21% |

57.08% |

15.92% |

|

Modal |

2= X |

0.468 |

38.65% |

8.79% |

24.15% |

|

Modal |

3 = Z |

0.449 |

32.82% |

6.92% |

32.07% |

The equivalent static analysis shows that the total base shear for both the control model and the experimental model with 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis reaches a maximum value of 860.74 tons in the X and Y directions.

This behavior indicates that the variation in material stiffness does not generate significant differences in the global structural response, since the increase in stiffness of the experimental concrete is compensated by a more uniform redistribution of lateral forces. Consequently, both models maintain a similar capacity to resist horizontal seismic actions, demonstrating that the incorporation of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis does not negatively affect the global stability of the building but instead improves the response of structural elements, enhancing the performance of the concrete.

Regarding elastic drifts, the results of the static analysis show that the control concrete model exceeds the limit allowed by Norma E.030, which establishes a maximum value of 0.007 for buildings of this type. Specifically, the excess appears at level 5 in the Y direction, indicating lower lateral stiffness at that point of the structural system and the need to reinforce or increase stiffness to comply with the regulatory parameters.

On the other hand, the experimental concrete model with 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis complies with the drift limits at all levels, both in the X and Y directions. This result confirms the positive effect of the improved concrete on the overall stiffness of the system, allowing a more controlled response to lateral displacements and ensuring greater structural stability under seismic loads.

Likewise, the dynamic analysis shows that both models comply with the established drift limit, demonstrating good structural performance. In the static analysis, the control concrete exceeds the maximum allowed value at level 5 in the Y direction, indicating lower lateral stiffness, while the experimental concrete with 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis maintains admissible drifts at all levels, showing better response to lateral loads.

4. Discussion

- In the present research, the first specific objective was to analyze the characterization of Biochar as an additive for a concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm², based on the article by [7] and [8], who mention that biochar presents a porous structure and high surface area that can act as a microfiller and improve the compaction of concrete mixes. In addition, previous experimental studies indicate that low doses of Biochar tend to improve cement hydration and compressive strength, while higher doses affect workability [9] and [8].

Likewise, [10] indicates that Biochar is a carbonaceous material obtained by pyrolysis of organic waste, reaching temperatures above 500 °C, followed by a grinding and sieving process, where mesh No. 50 is considered ideal for its uniformity. In accordance with this, the Biochar used in this study was produced by open pyrolysis with a calcination degree between 500 °C and 700 °C, obtaining greater retention in meshes No. 30 and No. 50, with a fineness modulus of 3.2, a value that falls within the acceptable range for fine aggregates according to NTP 400.037. These results partially coincide with those of [10], agreeing on the calcination degree but differing in granulometry, due to variations in raw material and the manual grinding process.

However, the obtained fineness modulus differs only by 0.02 units upper normative limit, confirming that Biochar presents a slightly coarser structure than a fine aggregate, but technically valid for use as an additive, as supported by item 5.3 of NTP 400.037. Therefore, the experimental characterization validates the technical potential of Biochar as an additive, provided that its production is standardized and its dosage adjusted in the concrete design.

- The second specific objective was to perform the bacterial culture of Bacillus subtilis for its use as an additive in a concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm². Based on the contributions of [11] and [12], they mention that this bacterium is gram-positive and non-pathogenic, which directly influences the fresh state of the concrete, allowing its survival within the concrete matrix.

During the development, the culture was carried out under controlled conditions, achieving pure growth with visible colonies of Bacillus subtilis. This result evidences an adequate handling of the culture process and coincides with what was reported by [13], who state that bacterial survival depends on pH control and cell concentration, which can reach optimal values in the order of 10⁸ cells/ml.

Likewise, the results agree with those indicated by [11] and [14] , who affirm that the efficacy of the culture depends both on bacterial resistance to pH and on the concentration method applied. In this research, a concentration of 2.8 × 10⁸ cells/ml was used, with the McFarland method, which, although lower than that used by [15], which was 1×10⁹ cells/ml, allowed obtaining significant improvements in mechanical properties without altering the physical properties of the concrete.

Therefore, the culture obtained in the present research meets the adequate microbiological parameters for its application in concrete mixes, confirming its potential as a biocatalytic agent capable of improving the microstructure of concrete.

- The third specific objective was to estimate the optimal percentage of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis addition for a concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm². In this sense, the combination of 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis represents the optimal addition percentage to improve the physical-mechanical properties of concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm². This combination achieved a slump of 9.91 cm, unit weight of 2379 kg/m³, and temperature of 27 °C, values very close to the control concrete, indicating that workability remains within the established range according to NTP 339.046. This demonstrates that the joint incorporation of both additives does not negatively affect the consistency or density of fresh concrete, corroborating what was reported by [10] and [11], who also found that controlled addition of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis independently maintains the consistency and physical stability of the material.

Regarding the mechanical properties, the same optimal combination recorded significant increases of 322 kg/cm² in compression at 28 days, 30 kg/cm² in tension, and 50 kg/cm² in flexion. These results surpass those obtained by the control concrete and agree with the international background of [7] and [8], who demonstrated that Biochar promotes better cement hydration and contributes to the increase in strength. At the same time, the action of Bacillus subtilis favors the increase in strength and survival in an alkaline environment through bacterial encapsulation, as indicated by [16] and [17] . Therefore, the existence of an optimal joint addition percentage of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis that improves the physical-mechanical properties of concrete is experimentally verified.

Overall, these findings reinforce that excess Biochar reduced strength due to its porous nature, while higher doses of Bacillus subtilis could have caused interferences in the setting process; therefore, the balance between the amount of carbonaceous material and bacterial presence is essential to enhance mechanical performance without compromising the workability of concrete.

- The fourth specific objective was to compare the physical properties of the control and experimental concrete for a concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm². According to [11], physical properties such as granulometry, unit weight, and slump are decisive in the workability and density of concrete.

In the results obtained, the experimental concrete with the addition of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis showed a slight decrease in unit weight and slump compared to the control concrete, remaining within the ranges established by NTP 339.046, which sets a range of 7.5 to 15 cm in slump and 1842 to 2483 kg/m³ in unit weight. This behavior can be attributed to the higher porosity of Biochar and the interaction of bacterial biomass with the mixing water.

These results partially coincide with the findings of [10], who reported that the incorporation of biochar reduces the density of concrete but improves internal moisture retention. Likewise, [15] observed that the presence of Bacillus subtilis does not significantly alter the flowability of concrete, as long as controlled dosing is maintained.

Consequently, the physical properties of the experimental concrete remain within normative parameters, showing slight variations attributable to the incorporation of sustainable additives.

- The fifth specific objective was to determine the mechanical properties of the control and experimental concrete for a concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm². Therefore, the results obtained in the tests demonstrated that the experimental concrete, made with the combination of Biochar and Bacillus subtilis, showed significant increases compared to the control concrete. In compressive strength, an increase of approximately 4.54% was observed, evidencing a denser internal structure and better adhesion between paste and aggregates. In indirect tensile strength, the increase was 6.72%, reflecting greater internal cohesion and a decrease in crack propagation. Finally, flexural strength showed an increase of 51.70%, resulting combined effect between the compact microstructure and the biocementing action of the bacterium.

When contrasting these findings with international background, a marked coincidence is observed. [9] reported a 27.27% increase in tensile strength with the incorporation of 5% Biochar, attributing it to improved cement hydration. Similarly, [16] evidenced that the addition of encapsulated Bacillus subtilis allowed increasing mechanical strength by up to 2%, due to calcium carbonate precipitation in the pores of the concrete, but flexural strength decreased by 5%.

At the national level, the incorporation of Bacillus subtilis in different research studies showed improvements, as mentioned by [17], with a 24.93% increase in compressive strength and 20.07% in flexural strength; moreover, for [11], there was an increase of 10.80% in compressive strength and 10.16% in tensile strength, results that closely relate to those obtained in this research, but resembling the compressive strength of [19][18] , who obtained an improvement of 4.58%, but differing in flexural strength, since flexural strength decreased by 1.36%.

At the local level, [18][19] added Bacillus subtilis and recorded an 11.11% increase in compressive strength, 25% in tensile strength, and no increase in flexural strength. Similarly, [15] reported increases in compressive and flexural strength of 22.49% and 15.27%, respectively, and in the addition of Biochar carried out by [10], an increase in compressive strength of 18.56% was obtained with an addition percentage of 2%.

The coincidences are explained by the synergistic effect between both additives. However, the combinations generally show an increase compared to the control, but in comparison with the investigations, the increase is closely similar in compression and tension, while there is a significant improvement in flexural strength in the combination of 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis, surpassing the results of the variables separately, thus obtaining a new sustainable and effective alternative to improve the mechanical properties of structural concrete.

- The sixth specific objective was to evaluate the linear seismic behavior of an eight-story building modeled with control and experimental concrete for a concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm². This structural analysis was carried out in the software ETABS 21, where it was evidenced that the experimental concrete of 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis presented shorter vibration periods compared to the control concrete, 0.529 s versus 0.535 s in “Y”, indicating greater overall rigidity of the system. This behavior was also reflected in the increase in lateral stiffness in X and Y, with approximate increases of 2.2% and 2.0%, respectively.

Regarding base shear, both models reached equivalent values, being 860.74 tons, demonstrating that the incorporation of additives did not alter the global distribution of seismic forces.

However, the elastic drifts of the control model exceeded the normative limit of 0.007, evidencing the need to reinforce stiffness on the fifth level, while the experimental model complied with the standard in all eight levels.

Finally, in the dynamic analysis, both models met the drift limits, although the experimental concrete showed a more stable and controlled behavior, attributed to the improvement in the physical-mechanical properties of the material.

5. Conclusions

- Analysis carried out on the characterization of Biochar as an additive for concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm², determined that the material meets the physical and granulometric properties required by NTP 400.037, presenting a structure compatible with traditional fine aggregate. Its porous texture, homogeneous coloration, and low specific weight demonstrate its potential as a sustainable additive. These results show that Biochar is technically suitable for incorporation into concrete mixtures.

- Bacterial cultivation process, verified that the developed Bacillus subtilis strain maintains high cell viability under controlled conditions and alkaline pH, demonstrating its ability to adapt to the cementitious environment. The results show the successful production of a pure, stable culture suitable for incorporation into the experimental concrete mixture.

- The study allows the identification of an optimal combined addition percentage of 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis for concrete f’c = 280 kg/cm², a combination that generates significant improvements in its physical–mechanical properties compared to the control concrete. This optimized percentage maintains adequate workability and stable density while increasing mechanical strength. Consequently, the results of the statistical tests confirm significant differences between the control concrete and the mixtures with joint addition.

- Comparative analysis between the control concrete and the experimental concrete with Biochar and Bacillus subtilis, observed that both maintain their properties within the ranges established by NTP 339.046. The experimental concrete presents a slight decrease in slump and unit weight, attributed to the porous nature of Biochar and the bacterial interaction in the mixture, without significantly affecting its workability or compactness. These results confirm that the combined addition does not negatively alter the physical properties of the concrete.

- Analysis of the compression, indirect tension, and flexural tests, determined that the experimental concrete with the addition of 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis achieves higher strengths than the control concrete, recording increases of 4.54%, 6.72%, and 51.70%, respectively. This behavior is due to the synergistic effect of Biochar as a microfiller and the bacteria as a biocatalyst agent in the formation of calcium carbonate. The notable improvement in flexural strength demonstrates a greater capacity of the material to resist tensile stresses in its tensile zone, reflecting a more cohesive and integrated structure.

- The modeling with experimental concrete containing 2% Biochar and 4.5% Bacillus subtilis shows superior seismic performance compared to the control concrete, with shorter periods, greater lateral stiffness, and drifts within the limits established by Standard E.030. The difference in compressive strength of 313 kg/cm² for the experimental concrete versus 299.4 kg/cm² for the control concrete directly influences structural stability, reducing global deformability and improving the dynamic response of the system.

6. Patents

Funding: This research received no external funding

Data Abbrevailability Statement: We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments: The authors sincerely thank their academic advisor and the laboratory team for their valuable guidance and technical support during the development of this research.

Confliaticts of Interenst: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

|

NTP |

Peruvian Technical Standard |

|

INACAL |

National Institute for Quality |

|

BHI |

Brain Heart Infusion |

|

ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

|

TSA |

Tryptic Soy Agar |

|

MYP |

Mannitol Egg Yolk Polymyxin Agar |

References

[1] Muñoz, S., Carlos, J., & Peralta, M. (2023). Influencia de las bacterias en la autocuración del concreto. Revista UIS Ingenierías, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.18273/revuin.v22n1-2023007

[2] Quispe, A. F., & Vasquez, J. N. (2023). Uso de bacteria Bacillus Subtilis en auto-reparación del proceso de fisuración por flexión en vigas [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, Universidad Nacional de Huancavelica]. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14597/6191

[3] Yuan, Q., Shi, Y., & Li, M. (2024). A Review of Computer Vision-Based Crack Detection Methods in Civil Infrastructure: Progress and Challenges. Remote Sensing, 16(16), 2910. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16162910

[4] Verano, P. (2025, febrero 20). Más de 200 puentes colapsados o dañados por las lluvias en Perú en los últimos tres meses. https://rpp.pe/peru/actualidad/mas-de-200-puentes-colapsados-o-danados-por-las-lluvias-en-peru-en-los-ultimos-tres-meses-noticia-1617197

[5] Comexperu. (2025). CERRAR LA BRECHA EN INFRAESTRUCTURA EDUCATIVA COSTARÍA S/ 158,832 MILLONES. COMEXPERU - Sociedad de Comercio Exterior Del Perú. https://www.comexperu.org.pe/articulo/cerrar-la-brecha-en-infraestructura-educativa-costaria-s-158832-millones

[6] Ministerio de Salud. (2021). DIAGNÓSTICO DE BRECHAS DE INFRAESTRUCTURA y EQUIPAMIENTO DEL SECTOR SALUD (p. 21). Ministerio de Salud. https://www.minsa.gob.pe/Recursos/OTRANS/08Proyectos/2021/DIAGNOSTICO-DE-BRECHAS.pdf

[7] Suárez, A. S. Z., Sanchez, L. M. A., & Vera, M. S. A. (2023). Diseño de hormigón hidráulico con biocarbon. South Florida Journal of Development, 4(7), 2927-2944. https://doi.org/10.46932/sfjdv4n7-030

[8] Zhou, Z., Wang, J., Tan, K., & Chen, Y. (2023). Enhancing Biochar Impact on the Mechanical Properties of Cement-Based Mortar: An Optimization Study Using Response Surface Methodology for Particle Size and Content. Sustainability, 15(20), 14787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014787

[9] Barissov, T. (2021). Application of Biochar as Beneficial Additive in Concrete [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, University of Nebraska]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/civilengdiss/175

[10] Salvador, J. (2023). Evaluación de las propiedades físicas y mecánicas del concreto f’c 210 kg/cm2, sustituyendo parcialmente el cemento por biocarbón de restos de madera, en la ciudad de Chiclayo [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil ambiental, Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo]. http://tesis.usat.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12423/6846

[11] Huaynalaya, M., Herradda, J. A., Jiménez, H. M., & Zapata, J. M. (2024). Influencia de la bacteria Bacillus Subtilis en la reparación de fisuras en concretos con a/c de 0.45 y 0.50. TecnoHumanismo, 4(2), 16-30. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9862387

12] Yamasamit, N., Sangkeaw, P., Jitchaijaroen, W., Thongchom, C., Keawsawasvong, S., & Kamchoom, V. (2023). Effect of Bacillus subtilis on mechanical and self-healing properties in mortar with different crack widths and curing conditions. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 7844. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34837-x

[13] Espitia, M. E., Pulido, D. E. C., Oliveros, P. A. C., Medina, J. A. R., Bello, Q. Y. O., & Fuentes, M. S. P. (2019). Mechanisms of encapsulation of bacteria in self-healing concrete: Review. DYNA, 86(210), 17-22. https://doi.org/10.15446/dyna.v86n210.75343

[14] Ezenarro, J. J., Mas, J., Muñoz-Berbel, X., & Uria, N. (2022). Advances in bacterial concentration methods and their integration in portable detection platforms: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1209, 339079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2021.339079

[15] Cubas, J. M., & Saldaña, R. Y. (2023). Influencia de la Bacteria Bacillus subtilis en las propiedades mecánicas del concreto bioautorreparable f’c 280 kg/cm2, Chiclayo [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, Universidad César Vallejo]. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/135262

[16] Perez, M. Y., & Merchan, J. D. (2022). EVALUACIÓN DE LAS PROPIEDADES MECÁNICAS EN EL CONCRETO AUTOREPARABLE A BASE DE BACTERIAS BACILLUS SUBTILIS Y EN EL CONCRETO CONVENCIONAL [Trabajo de Grado para optar al título de Ingeniero Civil, UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE COLOMBIA]. https://hdl.handle.net/10983/30425

[17] Fernandez, A. A. (2024). Efecto de la bacteria bacillus subtilis en la resistencia mecánica del concreto a temperatura de fraguado de 5°c [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, Universidad César Vallejo]. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/146574

[18] Castañeda, E. (2023). Influencia de la aplicación de la bacteria Bacillus Subtilis en la resistencia mecánica del concreto celular [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil ambiental, Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo]. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12423/6283

[19] Quevedo Iwamatsu, H. C. A., & Sánchez Guevara, E. O. (2021). Efecto de la bacteria (bacillus subtilis) en la resistencia a la compresión y flexión del concreto f´c= 210 kg/cm2. Repositorio Institucional - UCV. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/74346

|

NTP |

Peruvian Technical Standard |

|

INACAL |

National Institute for Quality |

|

BHI |

Brain Heart Infusion |

|

ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

|

TSA |

Tryptic Soy Agar |

|

MYP |

Mannitol Egg Yolk Polymyxin Agar |

References

- Muñoz, S., Carlos, J., & Peralta, M. (2023). Influencia de las bacterias en la autocuración del concreto. Revista UIS Ingenierías, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.18273/revuin.v22n1-2023007.

- Quispe, A. F., & Vasquez, J. N. (2023). Uso de bacteria Bacillus Subtilis en auto-reparación del proceso de fisuración por flexión en vigas [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, Universidad Nacional de Huancavelica]. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14597/6191.

- Yuan, Q., Shi, Y., & Li, M. (2024). A Review of Computer Vision-Based Crack Detection Methods in Civil Infrastructure: Progress and Challenges. Remote Sensing, 16(16), 2910. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16162910.

- Verano, P. (2025, febrero 20). Más de 200 puentes colapsados o dañados por las lluvias en Perú en los últimos tres meses. https://rpp.pe/peru/actualidad/mas-de-200-puentes-colapsados-o-danados-por-las-lluvias-en-peru-en-los-ultimos-tres-meses-noticia-1617197.

- Comexperu. (2025). CERRAR LA BRECHA EN INFRAESTRUCTURA EDUCATIVA COSTARÍA S/ 158,832 MILLONES. COMEXPERU - Sociedad de Comercio Exterior Del Perú. https://www.comexperu.org.pe/articulo/cerrar-la-brecha-en-infraestructura-educativa-costaria-s-158832-millones.

- Ministerio de Salud. (2021). DIAGNÓSTICO DE BRECHAS DE INFRAESTRUCTURA y EQUIPAMIENTO DEL SECTOR SALUD (p. 21). Ministerio de Salud. https://www.minsa.gob.pe/Recursos/OTRANS/08Proyectos/2021/DIAGNOSTICO-DE-BRECHAS.pdf.

- Suárez, A. S. Z., Sanchez, L. M. A., & Vera, M. S. A. (2023). Diseño de hormigón hidráulico con biocarbon. South Florida Journal of Development, 4(7), 2927-2944. https://doi.org/10.46932/sfjdv4n7-030.

- Zhou, Z., Wang, J., Tan, K., & Chen, Y. (2023). Enhancing Biochar Impact on the Mechanical Properties of Cement-Based Mortar: An Optimization Study Using Response Surface Methodology for Particle Size and Content. Sustainability, 15(20), 14787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152014787.

- Barissov, T. (2021). Application of Biochar as Beneficial Additive in Concrete [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, University of Nebraska]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/civilengdiss/175.

- Salvador, J. (2023). Evaluación de las propiedades físicas y mecánicas del concreto f’c 210 kg/cm2, sustituyendo parcialmente el cemento por biocarbón de restos de madera, en la ciudad de Chiclayo [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil ambiental, Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo]. http://tesis.usat.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12423/6846.

- Huaynalaya, M., Herradda, J. A., Jiménez, H. M., & Zapata, J. M. (2024). Influencia de la bacteria Bacillus Subtilis en la reparación de fisuras en concretos con a/c de 0.45 y 0.50. TecnoHumanismo, 4(2), 16-30. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9862387.

- Yamasamit, N., Sangkeaw, P., Jitchaijaroen, W., Thongchom, C., Keawsawasvong, S., & Kamchoom, V. (2023). Effect of Bacillus subtilis on mechanical and self-healing properties in mortar with different crack widths and curing conditions. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 7844. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34837-x.

- Espitia, M. E., Pulido, D. E. C., Oliveros, P. A. C., Medina, J. A. R., Bello, Q. Y. O., & Fuentes, M. S. P. (2019). Mechanisms of encapsulation of bacteria in self-healing concrete: Review. DYNA, 86(210), 17-22. https://doi.org/10.15446/dyna.v86n210.75343.

- Ezenarro, J. J., Mas, J., Muñoz-Berbel, X., & Uria, N. (2022). Advances in bacterial concentration methods and their integration in portable detection platforms: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1209, 339079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2021.339079.

- Cubas, J. M., & Saldaña, R. Y. (2023). Influencia de la Bacteria Bacillus subtilis en las propiedades mecánicas del concreto bioautorreparable f’c 280 kg/cm2, Chiclayo [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, Universidad César Vallejo]. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/135262.

- Perez, M. Y., & Merchan, J. D. (2022). EVALUACIÓN DE LAS PROPIEDADES MECÁNICAS EN EL CONCRETO AUTOREPARABLE A BASE DE BACTERIAS BACILLUS SUBTILIS Y EN EL CONCRETO CONVENCIONAL [Trabajo de Grado para optar al título de Ingeniero Civil, UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE COLOMBIA]. https://hdl.handle.net/10983/30425.

- Fernandez, A. A. (2024). Efecto de la bacteria bacillus subtilis en la resistencia mecánica del concreto a temperatura de fraguado de 5°c [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil, Universidad César Vallejo]. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/146574.

- Quevedo Iwamatsu, H. C. A., & Sánchez Guevara, E. O. (2021). Efecto de la bacteria (bacillus subtilis) en la resistencia a la compresión y flexión del concreto f´c= 210 kg/cm2. Repositorio Institucional - UCV. https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/74346.

- Castañeda, E. (2023). Influencia de la aplicación de la bacteria Bacillus Subtilis en la resistencia mecánica del concreto celular [Tesis para oprtar el título de Ingeniero civil ambiental, Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo]. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12423/6283.