Protein transport into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum (ER) used to be seen as strictly cotranslational, i.e. coupled to protein synthesis in time and mechanism. In the course of the last decades, however, various classes of precursors of soluble and membrane proteins were found to be posttranslationally imported into the ER, i.e. without involving the ribosome. The first class to be identified were the small presecretory proteins, tail-anchored membrane proteins followed next. In both cases the information for ER-targeting within the respective precursor is released from the translating ribosome as part of the fully-synthesized precursor, i.e. before it can initiate ER-import. In the case of the small presecretory proteins, the information for ER-targeting and -translocation via the polypeptide-conducting Sec61-channel is a classical N-terminal signal peptide, which is released from the ribosome due to the small size of the precursor. In the second case, the information for ER-targeting and Sec61-independent membrane insertion is a C-terminal transmembrane helix, termed tail-anchor, which first facilitates ER-targeting and membrane insertion of the precursor and, subsequently, represents the single transmembrane domain of the so-called tail-anchored membrane protein. Here, we discuss the current state of insights into the components and mechanisms, which are involved in targeting of small presecretory proteins to and their subsequent translocation into the human ER. In closing we present a unifying hypothesis for ER protein translocation in terms of an energy diagram for Sec61-channel gating.

- endoplamsic reticulum

- ER protein import

- small presecretory proteins

- Sec61-chanel gating

- endoplamsic reticulum, ER protein import, small presecretory proteins, Sec61-chanel gating

1. Introduction

-

Introduction

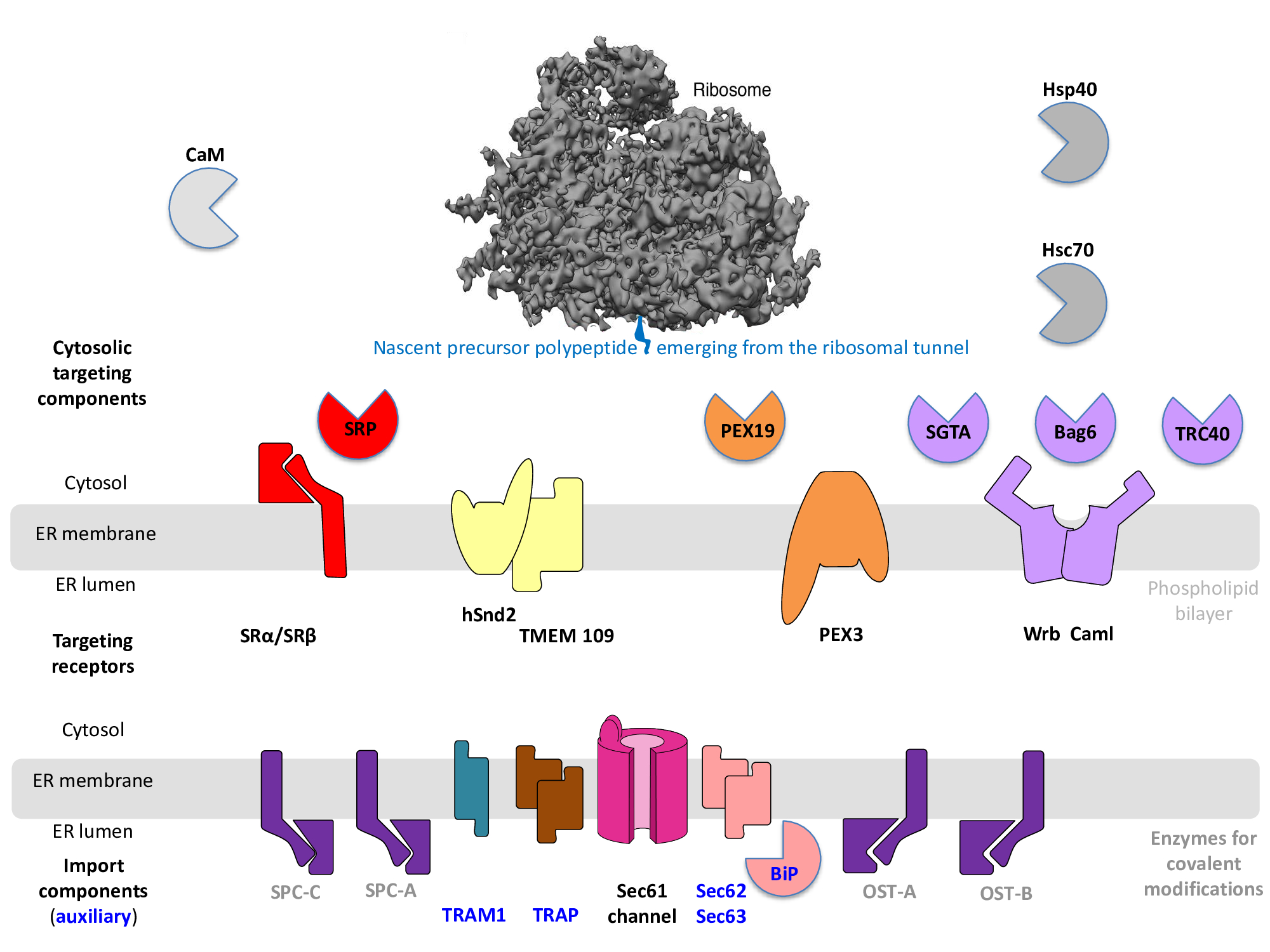

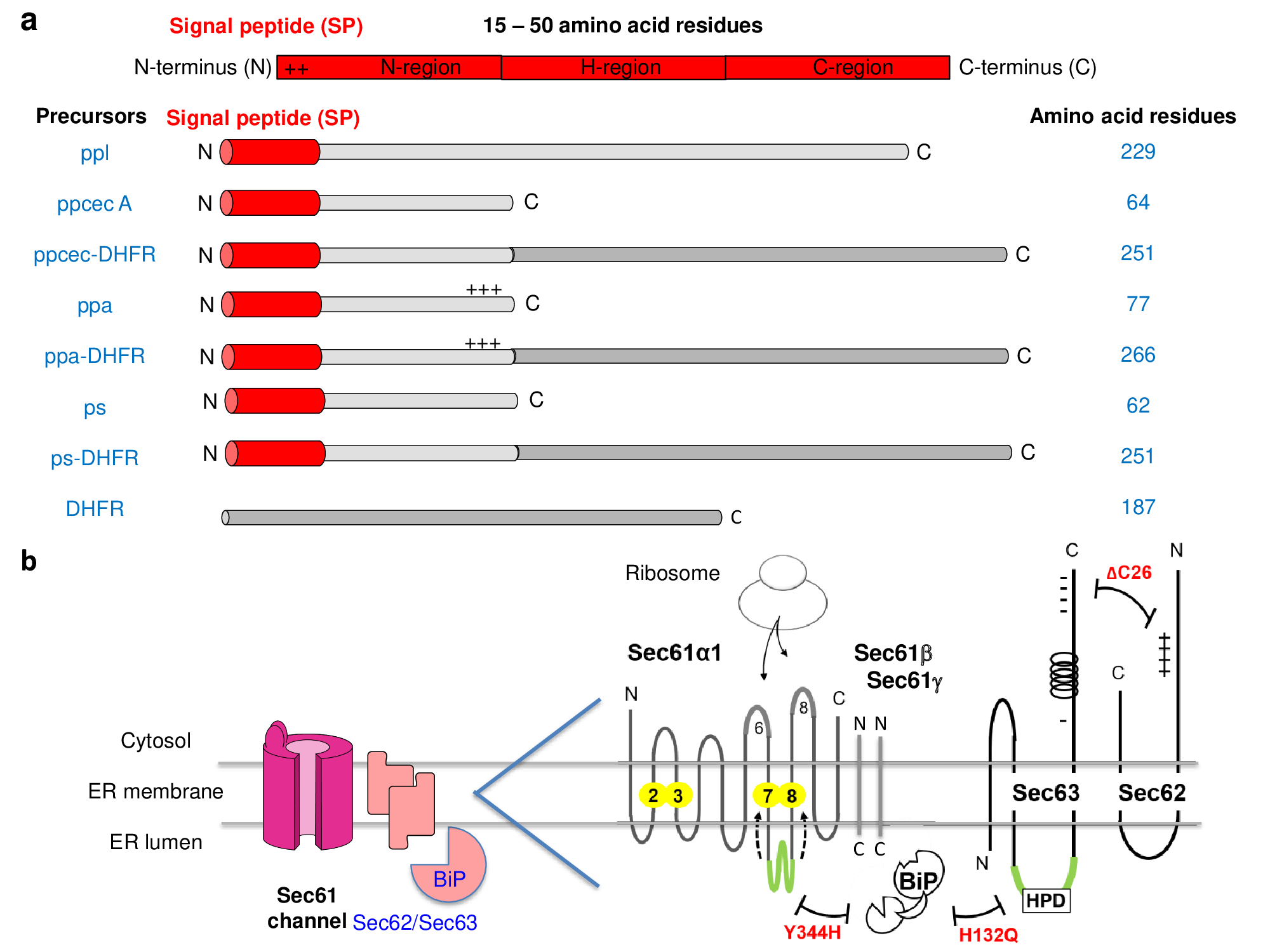

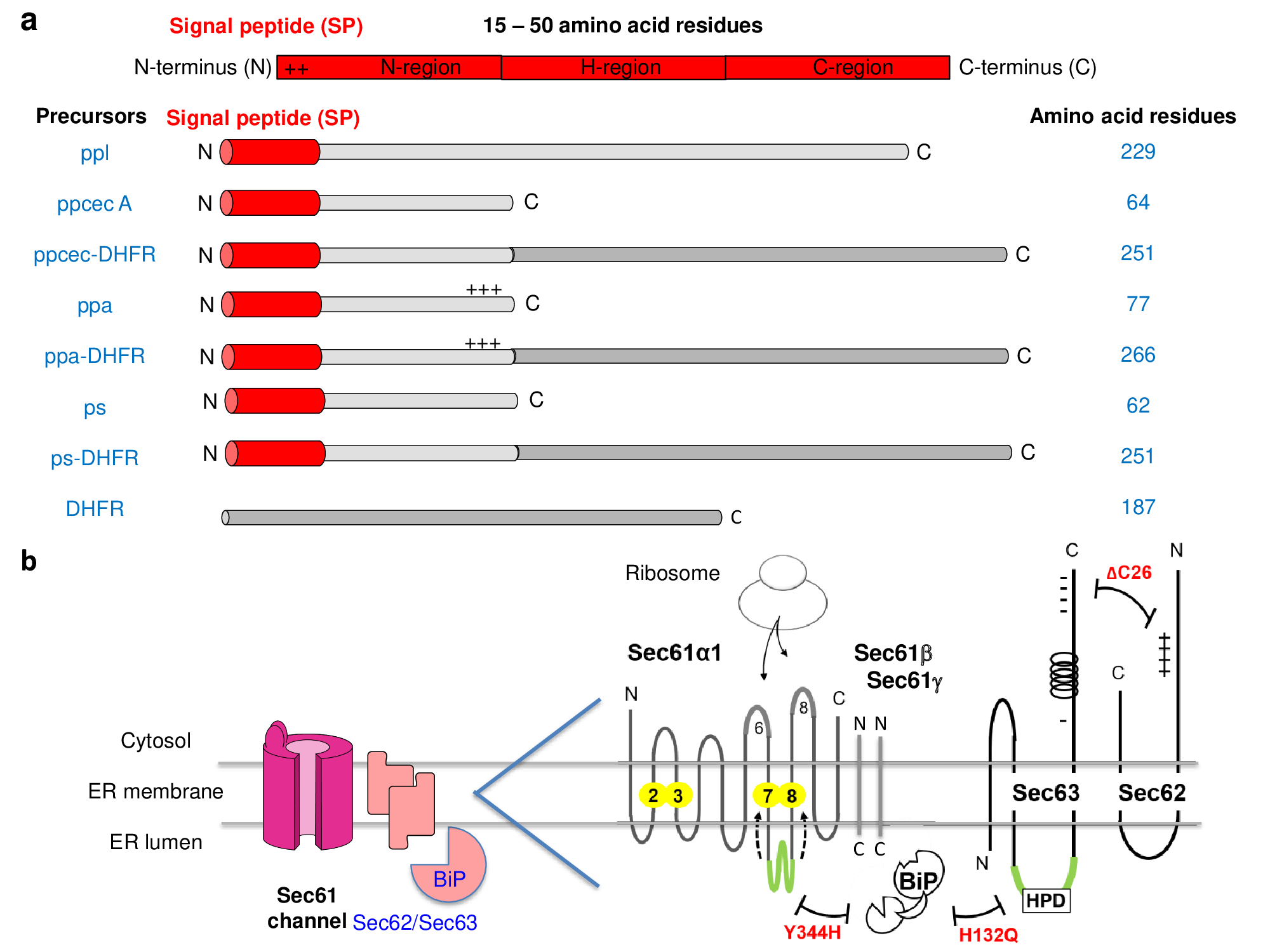

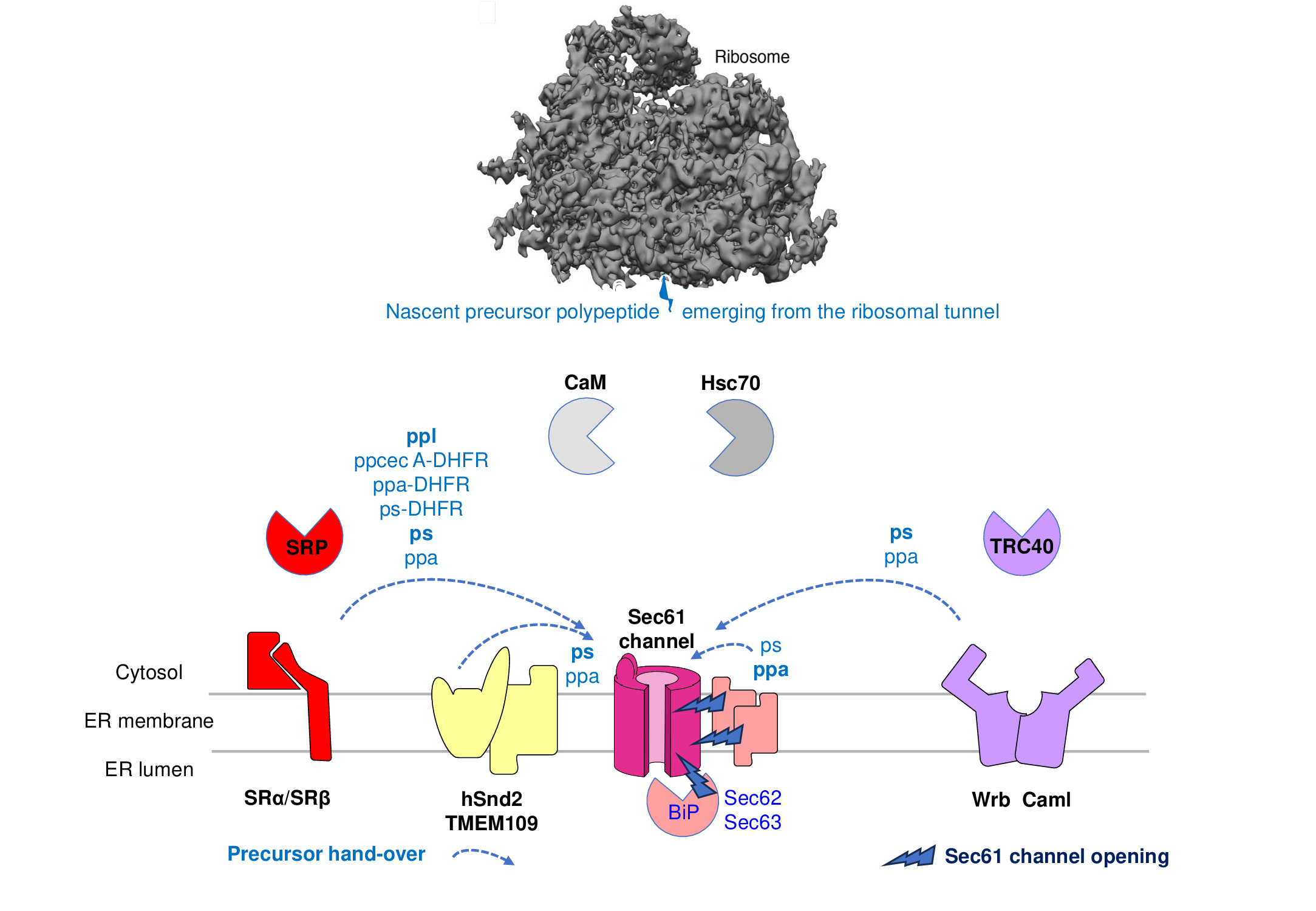

Transport into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the first step in the biogenesis of roughly ten-thousand different proteins or about one third of the proteome in humans [1][2][3][1][2][3]. This is true for most soluble and membrane proteins of organelles of the pathways of endo- and exocytosis as well as proteins of the plasma membrane and the extracellular space. Thus, transport into the ER represents the specific and complex insertion of membrane proteins into the ER-membrane or the specific import of soluble proteins into the ER-lumen. ER-transport involves signal peptides (SPs) or transmembrane helices (TMHs) for both ER-targeting and initial membrane insertion at the level of the respective precursor polypeptides plus various transport components, which decode this information and are present in the cytosol, the ER-membrane, and the ER-lumen (Figure 1) [4][5][4][5]. In the case of various types of membrane proteins -except for tail-anchored ones- the initial membrane insertion is followed by integration into the ER-membrane. In the case of soluble proteins, it is followed by completion of translocation into the ER-lumen. The information for ER-targeting and initial membrane-insertion within the precursor is either an N-terminal SP, which is typically cleaved off from the precursor upon ER-entry, or a more or less N-terminal TMH, which serves as a SP but -in contrast to a SP- remains a part of the mature protein. N-terminal SPs have a tripartite structure with a positively charged N-region, a central H-region, and a slightly polar C-region (Figure 2a) [4][5][4][5]. For most proteins, except for ER-resident proteins, transport into the ER is followed by vesicular transport to the functional intra- or extracellular location.

Figure 1. I Components that are involved in import and processing of presecretory proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of human cells. ER protein import comprises a targeting step plus a membrane translocation step. The two isozymes of SPC (Signal peptidase complex) and OST (Oligosaccharyltransferase), respectively, mediate typical covalent modifications of secretory proteins and plasma membrane proteins. OST-A and OST-B catalyze N-glycosylation and act either co- (OST-A) or posttranslationally (OST-B). SPCs catalyze the proteolytic removal of SPs. See text for details.

The first transport components, which were identified and characterized at the molecular level, were the cytosolic signal recognition particle (SRP) and its ER-membrane resident receptor, the heterodimeric SRP-receptor (SR) (Figure 1) [6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]13]. Today these components represent one of several ER-targeting pathways for precursor polypeptides, in this case for nascent precursor polypeptides in cotranslational transport (Figure 1) [4][5][4][5]. Notably, however, SRP and SR can also act posttranslationally, albeit with lower efficiency [14][14]. In cotranslational transport, SRP binds to N-terminal SPs or SP-equivalent TMHs as they emerge from the ribosomal tunnel exit, i.e. during translation[6][7][8][9] [6][7][8][9]. As a result, translation is slowed down until the ribosome-SRP-nascent chain complex interacts with SR at the ER surface in a GTP-regulated process. Next, both the translating ribosome and the nascent precursor polypeptide chain are handed-over to the so-called protein-translocon in the ER-membrane and translation is allowed to pick up speed. In the course of this hand-over the SP -with the help of the ribosome- initiates initial insertion of the nascent precursor polypeptide into the ER-membrane -more precisely- insertion into the heterotrimeric Sec61 complex in the ER-membrane, which -in its fully open state- forms an aqueous polypeptide-conducting channel through the ER-membrane [15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] [24][25]. Thus, SPs facilitate not only ER-targeting but also full Sec61-channel opening. A priori, SPs or their equivalents can insert into the Sec61-channel in a head-on (NER-lumen-Ccytosol) or in a loop (Ncytosol-CER-lumen) configuration and start sampling the cytosolic funnel of the Sec61-channel pore, i.e. start their dwell time in the Sec61-channel pore. Nascent membrane proteins leave the Sec61-channel with their transmembrane domain(s) laterally into the phospholipid bilayer via the so-called lateral gate of the channel, while the nascent precursors of soluble proteins leave it into the ER-lumen. In the case of precursors of soluble or membrane proteins with N-terminal SPs the latter are cleaved off from the nascent polypeptide chain by one of the two ER-membrane resident signal peptidases, which have their active sites in the ER lumen (Figure 1) [26][26].

Since N-terminal SPs for transport into the ER typically comprise 25-30 amino acid residues and 40-45 amino acid residues of a nascent polypeptide chain are buried in the ribosomal tunnel at any given time of elongation, a nascent precursor polypeptide with 65-75 amino acid residues is required for ER targeting and subsequent initial insertion into the Sec61-channel to operate cotranslationally. This is the reason why precursors with less than these roughly 70 amino acid residues in over-all length were originally expected to and indeed turned out to be different (Figure 2a) [27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][27][28][29][30] [31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49]. Notably, it was observed that shortening of a naturally occurring large presecretory protein, such as bovine preprolactin, to 86 amino acid residues led to a transport incompetent polypeptide, unless it was artificially kept on the translating ribosome as peptidyl-tRNA [8][9][8][9].

Figure 2. I Model presecretory proteins and some of their translocation components. (a) Key features of signal peptides and model proteins are shown. (b) On the left, the cartoon depicts the Sec61-channel with open lateral gate as well as open aqueous channel and with its allosteric effectors, Sec62, Sec63, and BiP. On the right, the scheme depicts the enlarged a-subunit of the heterotrimeric Sec61-channel together with its b- and g-subunit and its three allosteric channel effectors. In the Sec61 a-subunit transmembrane helices 2, 3, 7, and 8 that are forming the lateral gate (in yellow) and cytosolic loops 6 and 8 that are involved in ribosome binding are highlighted, as is ER-lumenal loop 7 (in green) that is containing the interaction site for BiP´s substrate-binding domain. In addition, a crucial sequence motif (HPD in the J-domain of Sec63, shown in green) and inactivating mutations (in red) in Sec61a1, Sec62, and Sec63 are indicated, as are N- and C-termini and important clusters of charged amino acid residues. Of note, a synthetic hybrid between ppcec A and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) was observed to be imported both cotranslationally (with the aid of SRP and ribosome) and posttranslationally (without the involvement of the two ribonucleoparticles) during its in vitro synthesis in reticulocyte lysate in the presence of canine pancreatic microsomes. The distinction between these two modes of translocation was possible by adding methotrexate to the import reaction. The drug only forms a tight complex with a fully-synthesized and folded DHFR-moiety in the hybrid protein and in doing so inhibits translocation [34][34].

Figure 2. I Model presecretory proteins and some of their translocation components. (a) Key features of signal peptides and model proteins are shown. (b) On the left, the cartoon depicts the Sec61-channel with open lateral gate as well as open aqueous channel and with its allosteric effectors, Sec62, Sec63, and BiP. On the right, the scheme depicts the enlarged a-subunit of the heterotrimeric Sec61-channel together with its b- and g-subunit and its three allosteric channel effectors. In the Sec61 a-subunit transmembrane helices 2, 3, 7, and 8 that are forming the lateral gate (in yellow) and cytosolic loops 6 and 8 that are involved in ribosome binding are highlighted, as is ER-lumenal loop 7 (in green) that is containing the interaction site for BiP´s substrate-binding domain. In addition, a crucial sequence motif (HPD in the J-domain of Sec63, shown in green) and inactivating mutations (in red) in Sec61a1, Sec62, and Sec63 are indicated, as are N- and C-termini and important clusters of charged amino acid residues. Of note, a synthetic hybrid between ppcec A and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) was observed to be imported both cotranslationally (with the aid of SRP and ribosome) and posttranslationally (without the involvement of the two ribonucleoparticles) during its in vitro synthesis in reticulocyte lysate in the presence of canine pancreatic microsomes. The distinction between these two modes of translocation was possible by adding methotrexate to the import reaction. The drug only forms a tight complex with a fully-synthesized and folded DHFR-moiety in the hybrid protein and in doing so inhibits translocation [34][34].

2. Small Presecretory Proteins

-

Small presecretory proteins

Since the 1970s, small secretory proteins and small hormones are known [48][48]. Typically, however, the latter are synthesized as large precursor proteins with more than 70 amino acid residues in over-all length, often with additional pro-peptides, which are cleaved from the pro-protein by converting enzymes late in the secretory pathway. Classical examples are preproinsulin or prepro-opiomelanocortin, which give rise to insulin and the bio-active peptides corticotropin and melanotropin gamma, respectively. These precursors comprise more than 100 amino acid residues and involve typical cotranslational ER-targeting (via SRP and SR) and ER-import.

With the beginning of DNA cloning and sequencing in the 1980s, the first small presecretory proteins with less than 70 amino acid residues in over-all length were identified in insects and amphibia and, as expected, were found to have the ability for posttranslational transport into canine pancreatic rough microsomes (i.e. vesicles derived from the rough ER) in cell-free systems for in vitro translation and transport, such as rabbit reticulocyte lysate[29][30][34] [29][30][34]. Examples are honeybee prepromelittin (70 amino acid residues or aas), prepropeptide GLa from Xenopus laevis (64 aas), and preprocecropin A (ppcec A) from Hyalophora cecropia (64 aas) (Figure 2a). These studies established that small presecretory proteins can indeed be posttranslationally imported into mammalian microsomes in a both ribosome- and SRP- and SR-independent fashion (more precisely termed ribonucleoparticle-independent transport, see legend to Figure 2b) and that these characteristics are related to the small size plus intrinsic features of the precursors, which allow them to stay transport competent in the cytosol (Figures 1 and 2a) [29][30][32][34][29][30][32][34]. Furthermore, the import reaction was shown to involve the hydrolysis of ATP. Subsequently, this ATP-requirement was attributed to two Hsp70-type chaperones, to the cytosolic Hsc70, which together with an Hsp40-type co-chaperone helps the precursors to stay transport competent in the cytosol, and to the ER-luminal BiP plus its nucleotide exchange factor Grp170, which together facilitate initial insertion of the precursor into the Sec61 complex and completion of translocation (Figure 1) [31][32][34][35][31][32][34][35]. In initial Sec61-channel insertion, BiP binds to the channel and facilitates its opening [43][43], in completion of translocation, BiP binds to the incoming polypeptide, acts as a molecular ratchet, and makes translocation unidirectional [40][40]. The latter was also observed to improve the transport efficiency of the classical SRP- and SR-dependent presecretory protein bovine preprolactin. This was demonstrated by the use of proteoliposomes, comprising the full complement of microsomal membrane proteins plus avidin in the lumen, and biotinylated nascent preprolactin chains [40][40]. Notably, avidin did not work for non-biotinylated precursors.

At the time, however, the general feeling in the field remained that posttranslational transport of SP bearing precursors of soluble proteins is an exceptional if not artificial mechanism, which can be used by only a couple of small exotic precursor polypeptides. Lately, this view has changed because of the simultaneous discovery of small and some not so small human precursor polypeptides (ß-defensin 2, ß-defensin 133, C-C motif chemokine 2, preresistin, preproinsulin, preproapelin (ppa), prestatherin (ps)), which can be posttranslationally and ribosome-independently transported into the mammalian ER, and because of the demonstration of posttranslational transport of one of the exotic precursor polypeptides, ppcec A, into the ER of intact human cells (Figure 2a) [42][44][45][46][42][44][45][46]. Subsequently, the combination of siRNA-mediated gene silencing and protein transport into the ER of semi-intact human cells in rabbit reticulocyte lysate showed that posttranslational and ribosome-independent transport of ppcec A into the human ER occurs independently of the SRP- and SR-targeting system and involves the ER membrane proteins Sec62 and Sec63 (a Hsp40-type co-chaperone of BiP), as well as the ER-luminal Hsp70-type chaperone BiP [49][49].

3. Small Presecretory Proteins in Mammals

-

Small presecretory proteins in mammals

With the advancement of cDNA sequencing projects and bioinformatic tools in the early years of the twenty first century, the first systematic compilations of small proteins and small presecretory proteins in mice and humans were made [48][48]. It turned out that 12% or 3701 of mouse proteins are shorter than 100 amino acids (defined as small) and that only 232 of the 3701 proteins matched database entries in 2006 and that 495 of the 3701 proteins lacked similarity to any known proteins in UniRef90. Furthermore, 91 of 1240 small ORFs were predicted to contain SPs, 117 of 1240 proteins were grouped into 38 families with two or more members, and 844 transcripts of the 1240 small ORFs were found to mainly function as hormones or antimicrobial peptides, the latter being reminiscent of the originally described small presecretory proteins in amphibians and insects. Furthermore, most of the 1240 small ORFs were observed to be expressed in a highly tissue-specific fashion, i.e. in neuronal tissue, haemopoietic cells and tissues, and embryonic cells and tissues. These compilations were the starting point for several labs to seriously look into the biogenesis of small human presecretory proteins and raises the question why it may have made sense in the course of evolution to allow small as well as large presecretory proteins (see below).

4. Targeting of Small Human Presecretory Proteins to the Human ER

-

Targeting of small human presecretory proteins to the human ER

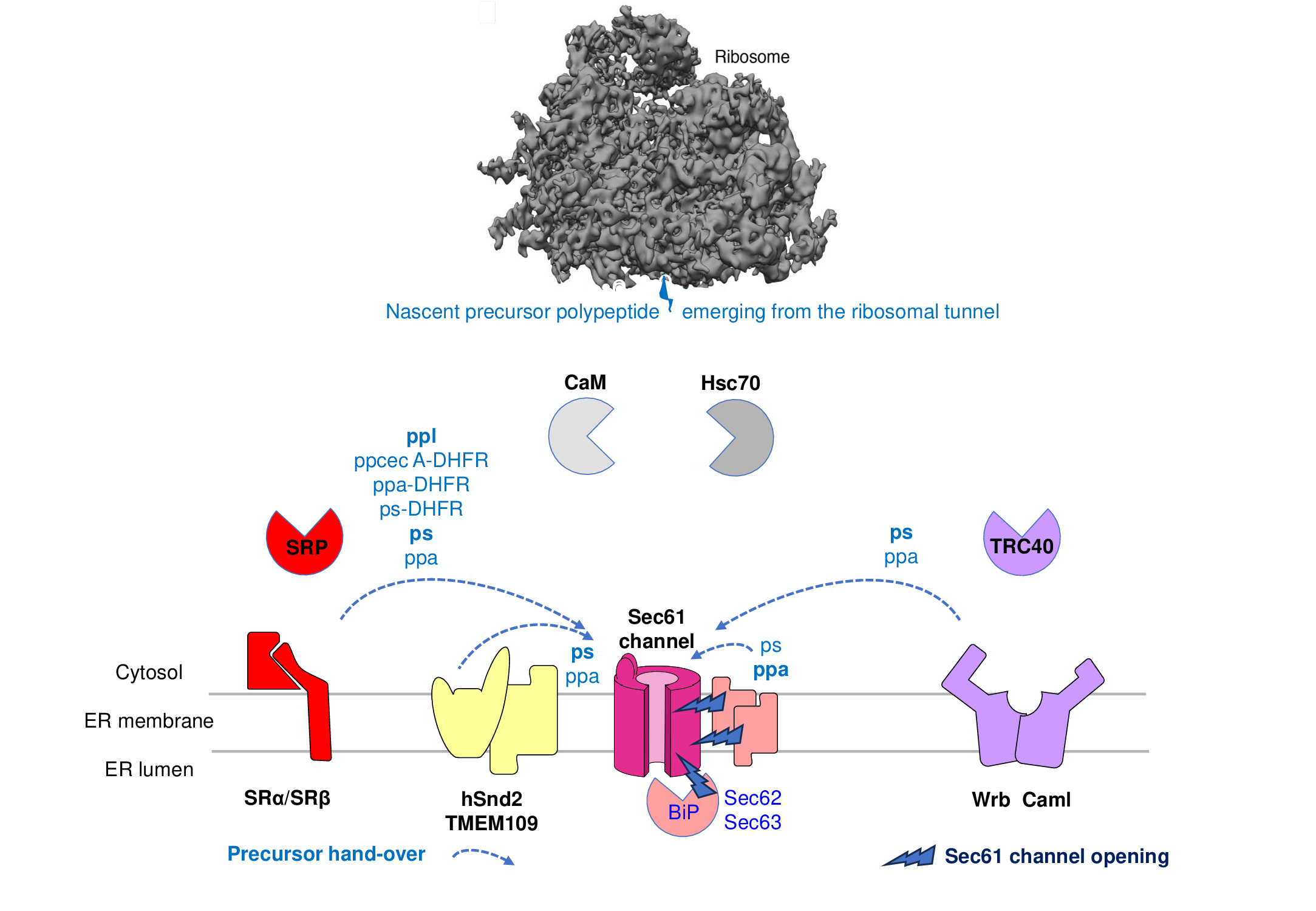

Originally, posttranslational and ribosome-independent ER-import of several small human precursor polypeptides (ß-defensin 133 with 61 amino acid residues or aas, ps with 62 aas, ß-defensin 2 with 64 aas, ppa with 77 aas, C-C motif chemokine 2 with 99 aas, preresistin with 108 aas, and preproinsulin with 110 aas) into the human ER was observed. Subsequently, ER-targeting of ps, ppa, C-C motif chemokine 2, preresistin, and preproinsulin was reported to occur independently of SRP and its heterodimeric receptor in the ER-membrane (SR) and to involve cytosolic TRC40 or Sec62 in the ER-membrane (Figure 3)Figure [44][45][46]3)[44][45][46]. From these studies, the concept emerged that Sec62 and the TRC-system, comprising TRC40 in the cytosol in cooperation with its heterodimeric receptor in the ER-membrane (Wrb/Caml), may act as alternative SP recognition proteins in posttranslational ER-targeting (Figure 3). In addition, it also became clear from these studies that the presumed 100 amino acid residues content of small presecretory proteins is not that strict and that even the model presecretory proteins are quite different with respect to which targeting pathway they can use most efficiently [44][47][44][47]. Apparently, even the small precursors ppa and ps can use the SRP/SR-system in both its co- and its posttranslational mode of action. Although smaller in size, ps actually preferred SRα over Sec62-mediated targeting, which may be due to a C-terminally located peptide motif in the mature region of presthatherin, which is reminiscent of the translation-arrest peptide of XBP1 [47][47]. In contrast, ppa did the opposite, which may be related to the comparatively low hydrophobicity of its SP (delta Gpred -0.19 versus -0.91 for ps). Taken together with the observation that C-terminal extension of ppa or ps by the cytosolic protein dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR, 187 amino acid residues) leads to Sec62-independence, the data from small human presecretory proteins reiterated the notion that small precursors use the SRP/SR-system for ER-targeting in mammalian cells less effectively, simply because the corresponding precursor polypeptide chains are more likely to be released from ribosomes before SRP can efficiently interact [34][44][47][34][44][47]. Mammalian Sec62, however, does not only act as a SP receptor, but also plays a role in Sec61-channel gating (priming and/or full opening of the channel, see below).

Furthermore, Ca2+-Calmodulin (Ca2+-CaM), which is known to have an affinity for transmembrane domains, was described as an additional cytosolic SP binding protein in post-translational ER-targeting and was proposed to productively cooperate with an IQ-motif in the cytosolic N-terminus of Sec61a, e.g. in the case of targeting of ß-defensin 133 and ß-defensin 2 [42][42]. Interestingly, Ca2+-CaM can also bind to tail-anchors but when doing so inhibits their membrane insertion [50][51][50][51]]. In addition, yet another SRP-independent ER-targeting pathway was discovered in yeast, the SND-pathway, which was shown to involve an ER-membrane protein with a human ortholog, hSnd2 [52][52][53]. In yeast, Snd2 together with Snd3 forms a heterodimeric receptor in the ER-membrane, in this case for the cytosolic precursor- and ribosome-binding protein Snd1. Notably, however, mammalian orthologs of the yeast Snd1- and Snd3-components have not been identified[54]. So far, only ER-targeting of one small presecretory protein (ps) showed an hSND2-involvement, which was detected only in the simultaneous absence of the TRC-system [47][47].

Figure 3. I Components that are involved in import and processing of small model presecretory proteins into the human ER. The observed preferences of the model precursors for targeting components (in bold face) and their requirements for the membrane translocation step are indicated. See text for details.

5. Translocation of Small Human Presecretory Proteins into the Human ER

-

Translocation of small human presecretory proteins into the human ER

5.1. The Sec61 Ccomplex

The combination of siRNA mediated SEC61A1-gene silencing in HeLa cells and protein transport into the ER of the corresponding semi-intact cells demonstrated that posttranslational import of small human presecretory proteins into the human ER involves the Sec61 complex (comprising Sec61a1, Sec61ß, and Sec61g), i.e. the polypeptide-conducting channel of the classical SRP-dependent and cotranslational membrane insertion and translocation pathway, which is not involved in membrane insertion of tail-anchored membrane proteins (Figure 2b) [45][45]. The opening of the Sec61-channel during early steps of translocation can be envisaged in analogy to a ligand-gated ion channel, in this case the ligand being the nascent or fully-synthesized presecretory protein with its SP. However, gating by the ligand alone is not sufficient, allosteric channel effectors have to support it. Channel-opening occurs in two stages, a priming step, which involves the ribosome as allosteric channel-effector in cotranslational transport, and possibly, Sec62 in collaboration with or without Sec63 in posttranslational transport [23][23]. We note that, in contrast to yeast, where there is the so-called SEC-complex (a permanent assembly of a heterotrimeric Sec61 complex plus the heterotetrameric Sec62/Sec63/Sec71/Sec72-complex) that is supposedly dedicated to posttranslational protein import, the mammalian complex of Sec61, Sec62, and Sec63 appears to be assembled on demand rather than permanently, which was observed for cotranslational ER-import of the precursors of the prion protein and the ER-luminal protein ERj3[55][56]. This may be related to the fact that -in contrast to the yeast ER- the mammalian ER also serves as the main intracellular calcium reservoir and would not tolerate an even partially open Sec61-channel [18][43][18][43][57]. We further note, that the human genome also codes for Sec61a2, which does not seem to be present in HeLa cells to any significant extent and was not over-produced under conditions of SEC61A1-gene silencing, and that certain precursors (such as the precursors of the prion protein and the ER-luminal protein ERj3) involve Sec62, Sec63, and BiP in cotranslational import[55][56][58]. Databases indicate that expression of SEC61A2 is limited to the tissues of brain and testis, though ranging at low estimated levels. For productive precursor insertion into the Sec61-channel and concomitant opening of the aqueous pore within the Sec61-channel, i.e. the second step in channel-opening, a high hydrophobicity/low delta Gpred value for the H-region of the SP is conducive [23][23][58]. Apparently, H-region hydrophobicity is decoded by the so-called hydrophobic patch in the Sec61a transmembrane helices 2 and 7, which line the lateral gate of the channel (Figure 2b) [23][23]. Furthermore, high hydrophobicity of the SP favours its partitioning via the lateral gate into the phospholipid bilayer, which can be expected to contribute to full channel opening by a free energy gain, in analogy to the hydrophobic effect in protein folding. Typically, the SP-orientation in the Sec61-channel follows the positive inside rule, i.e. positively charged residues in the N-region support loop insertion, while positively charged side chains downstream of the SP interfere with loop insertion and favour head-on insertion (which are present in ppa) [47][47].

5.2. The Sec62/Sec63 Ccomplex

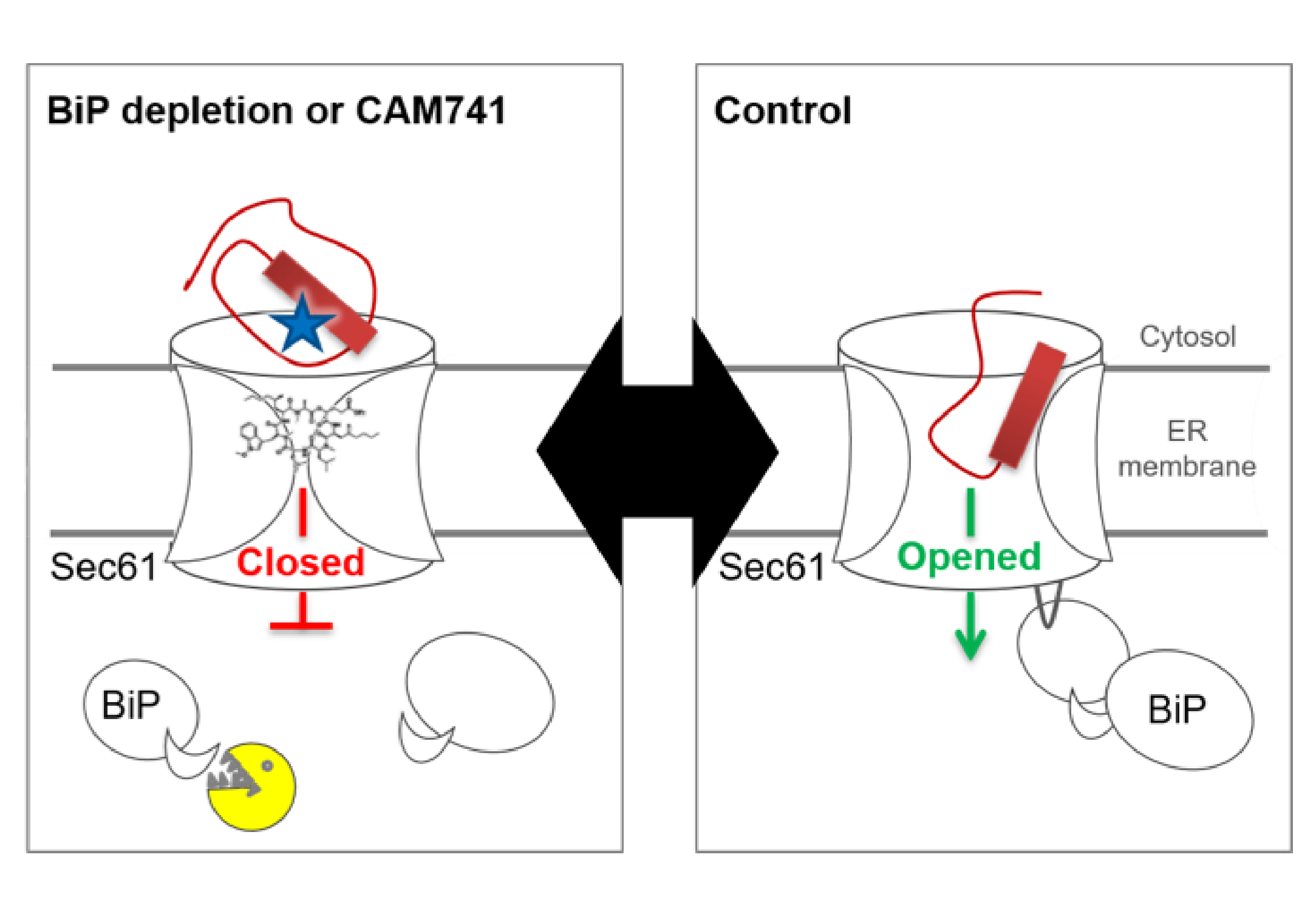

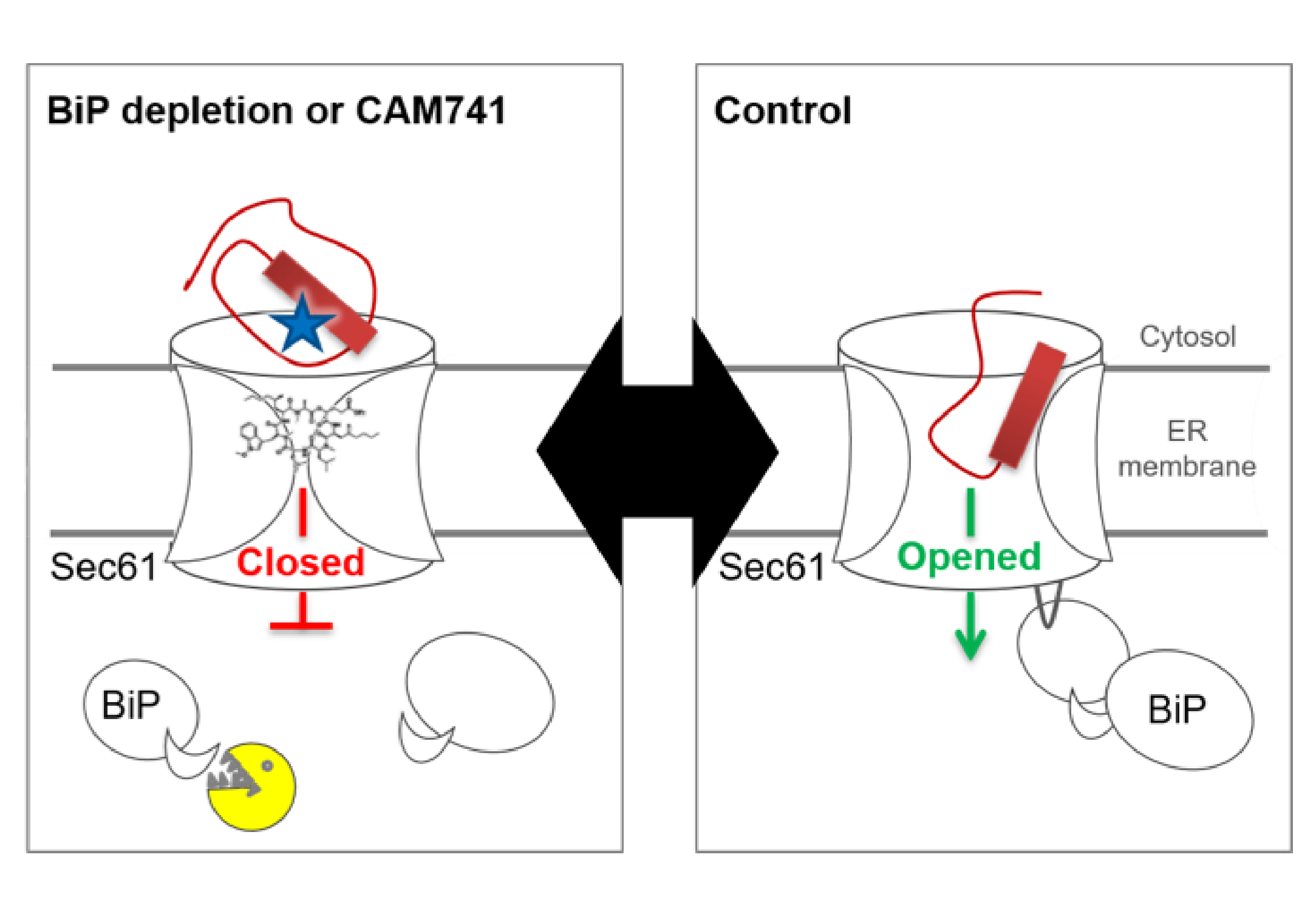

It was observed by the combination of siRNA mediated gene silencing in HeLa cells and protein transport into the ER of corresponding semi-intact cells that import of small precursor polypeptides into the human ER involves the ER membrane proteins Sec62 and Sec63 (for ppa and ps) plus, e.g. in the case of ppa, the ER-luminal Hsp70-type chaperone BiP, which cooperates with the Hsp40-type co-chaperone Sec63 (Figure 2b)[47]. The role of BiP in this early phase of ppa import was indirectly confirmed by ATP-depletion from the ER via depletion of the ER-membrane resident ATP/ADP exchanger AXER that is also termed SLC35B1[59]. From these studies the concept emerged that Sec62, Sec63, and BiP are involved in productive initial insertion of some precursor polypeptides into the Sec61 complex (such as ppa), as had originally been observed for the three yeast orthologs. According to the current model for the action of Sec62, Sec63 with or without BiP at this early stage of protein translocation, small presecretory proteins are unable to trigger full opening of the Sec61-channel, because of an inefficiently gating SP[47]. Therefore, the channel-opening has to be supported by Sec62/Sec63 (ps) or even by Sec62/Sec63-mediated binding of BiP to the ER-luminal loop 7 of Sec61a (ppa) (Figure 3). This view was supported by the observations that the murine diabetes linked mutation of tyrosine 344 to histidine within loop 7 destroys the BiP binding site and, when introduced into HeLa cells, prevents import of BiP-dependent precursor polypeptides, such as ppa (Figure 2b) [43][47][43][47].

Our observation -by chemical crosslinking- that small precursor polypeptides (such as ppa) accumulate within the Sec61-channel upon Sec62-, Sec63-, or BiP-depletion suggested a Sec61-gating function for these three proteins [47][47]. Furthermore, the small presecretory protein ps presented a remarkable phenotype, as it apparently involves Sec63 and Sec62 independently of BiP. Thus, at least in certain cases Sec63 itself can contribute to Sec61-channel gating, i.e. without involving BiP, most likely via its interaction with the Sec61 complex. Therefore, the question arises of which features of ppa or ps determine their dependence on Sec63 in Sec61-channel gating. The signal sequence swap variant preppl-proapelin (with the bovine preprolactin signal sequence in front of proapelin) suggests that the signal sequence contributes to requiring Sec63, at least for Sec63/Sec62- and most likely intrinsic Sec63-function [47][47]. Apparently, there are SPs efficient enough to trigger full opening of the ribosome-primed Sec61-channel, such as the bovine preprolactin signal sequence (Figure 2a). We attribute this efficiency to the consecutive interactions of the H-region with the hydrophobic patch within the channel and the phospholipid bilayer [23][23]. In contrast, other SPs like the signal sequences of ppa and ps require help from the auxiliary transport component Sec63 (Figure 2b). In addition to its intrinsic activity in protein translocation, Sec63 acts as Hsp40-type co-chaperone for ER-luminal Hsp70-type chaperone BiP. The collaboration of Sec63 and BiP involves the characteristic HPD-motif within the ER-luminal J-domain of Sec63 and the interacting surface of the ATPase domain of BiP (Figure 2b). Therefore, ppa, which depends on Sec63 plus BiP for efficient productive insertion into the Sec61 complex and Sec61-channel gating to the fully open state was sensitive to the SEC63H132Q and SEC61A1Y344H mutations (Figure 2b) [47][47]. Consequently, Sec63 and BiP depletion resulted in an accumulation of ppa within the Sec61-channel, which was detected by chemical crosslinking (Figure 4). In contrast, ps was not BiP-dependent and not sensitive to the two mutations.

5.3. The ER-Lluminal Cchaperone BiP

Although the SP of ppa was identified as a factor contributing to Sec63 dependence, it appeared not to be associated with requiring BiP [47][47]. Instead, the mature region contributed to the inefficiency of ppa in Sec61-channel gating. The mature region of ppa contains a cluster of three positively charged amino acid side chains near the C-terminus that weakens its gating property and causes the requirement for support by BiP. Thus, we suggest that the low gating efficiency of ppa results from the presence of two individual features, its SP and the cluster of positively charged amino acid residues within the mature region and, therefore, requires additional support from BiP (Figure 2a). Notably, the clusters of positive amino acid residues within the mature region of ppa contain the dibasic cleavage site for furin and plays a role in interaction of the mature hormone with its receptor. Thus, the chaperone BiP appears to compensate the deleterious effect of a cluster of charged residues within proapelin, which is required for maturation and subsequent biological activity. Interestingly, cotranslational ER-import of the large precursors of the prion protein and the ER-luminal protein ERj3 also involves Sec62, Sec63, and BiP, because of clusters of positive charges downstream of the SPs [43][45][43][45][55][56]. Though being deleterious for ER-import, presence of those charges relates again to the biological activity of the mature protein. Here, however, their effect on ER-import clearly depends on the properties of the preceding SP and its capacity for compensation. Thus, the combination of both, an inefficiently gating SP and downstream clusters of charges lead to a low gating efficiency of the prion protein- and ERj3-precursors. In contrast, low gating efficiency in the case of the small ppa is the result of individual features each one separately requiring specific factors for compensation. Therefore, the low gating capacity of the ppa SP remains in the absence of charges and so does the requirement for Sec62/Sec63 [47][47].

Based on these different observations on charged clusters in the mature regions of ppa and the precursors of prion protein and ERj3, we differentiate -depending on their distance to the SP- between a “cis-“ and a “trans-effect” on ER-import, though all clusters of charges being part of the translocating polypeptide chain. In the case of ppa, the cluster of charges may act “in trans” and impair precursor insertion into the Sec61-channel just like any charged peptide, endogenous or exogeneous, might do when in close proximity to the sampling SP within the channel. In the case of the precursors of prion protein and ERj3, the cluster of charges has to be part of the mature polypeptide chain at a certain effective distance to the SP to act “in cis” and to impair insertion of the preceding SP into the Sec61-channel according to the “positive-inside rule”. We suggest that such a positive cluster may favour “head-first” rather than “loop” insertion of the SP into the Sec61-channel, particularly in the case of precursors with a low number of positive charges in the N-region (such as in the case of prion protein and pre-ERj3). In this case, the required flip-turn of the SP may pose a particularly high energetic barrier or activation energy for Sec61-channel opening (see below).

Figure 4. I Scheme for Sec61-channel gating under different conditions. The cartoon illustrates that complete BiP-depletion by treatment of cells with subtilase cytotoxin SubAB (yellow pacman) and Sec61 inhibition by CAM741 (structural model) both prevent productive insertion of ppa into the Sec61-channel. This allows crosslinking of ppa to Sec61a (blue star).

Figure 4. I Scheme for Sec61-channel gating under different conditions. The cartoon illustrates that complete BiP-depletion by treatment of cells with subtilase cytotoxin SubAB (yellow pacman) and Sec61 inhibition by CAM741 (structural model) both prevent productive insertion of ppa into the Sec61-channel. This allows crosslinking of ppa to Sec61a (blue star).

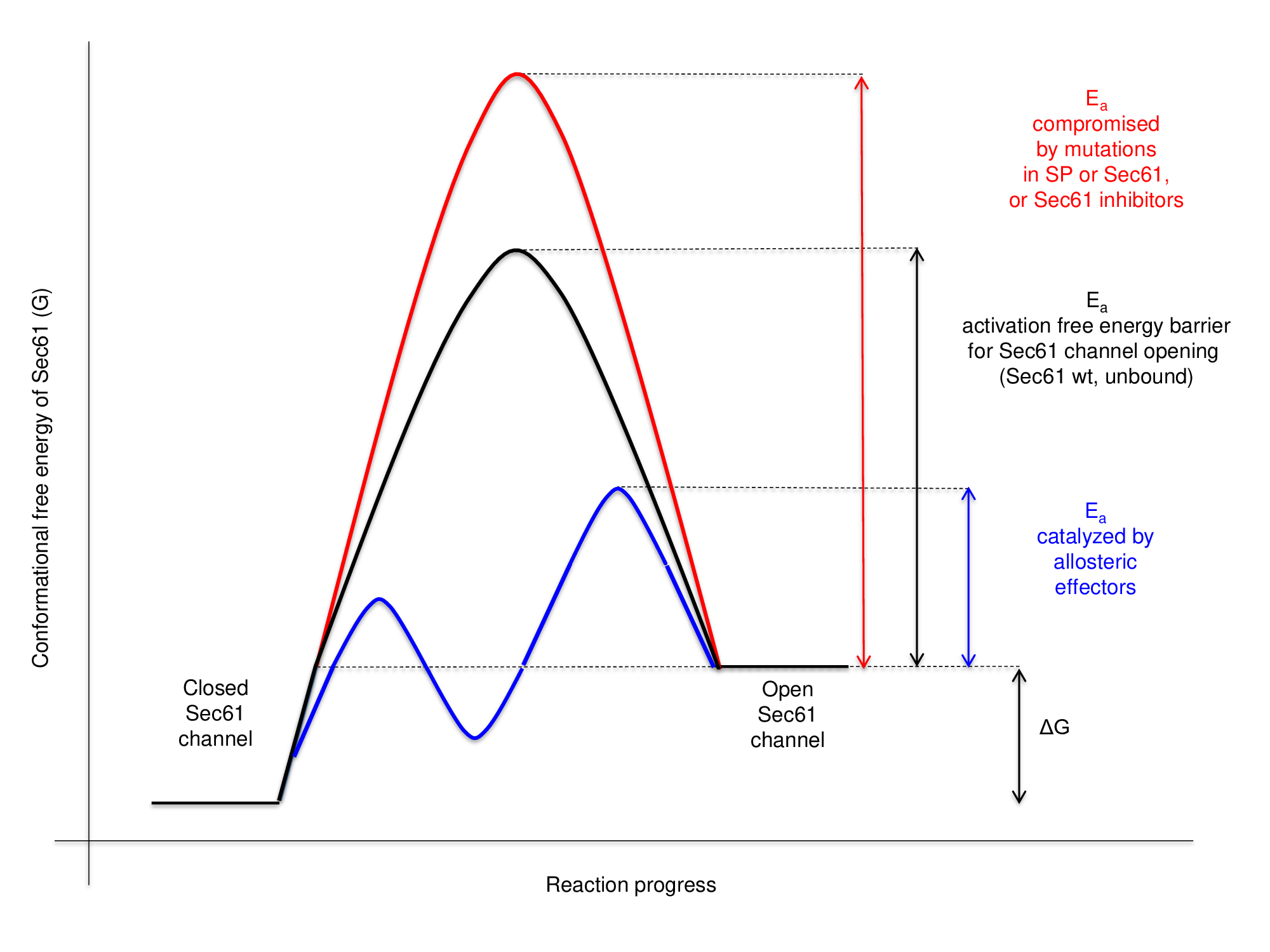

5.4. Free Eenergy Ddiagram for Sec61-Cchannel Ggating

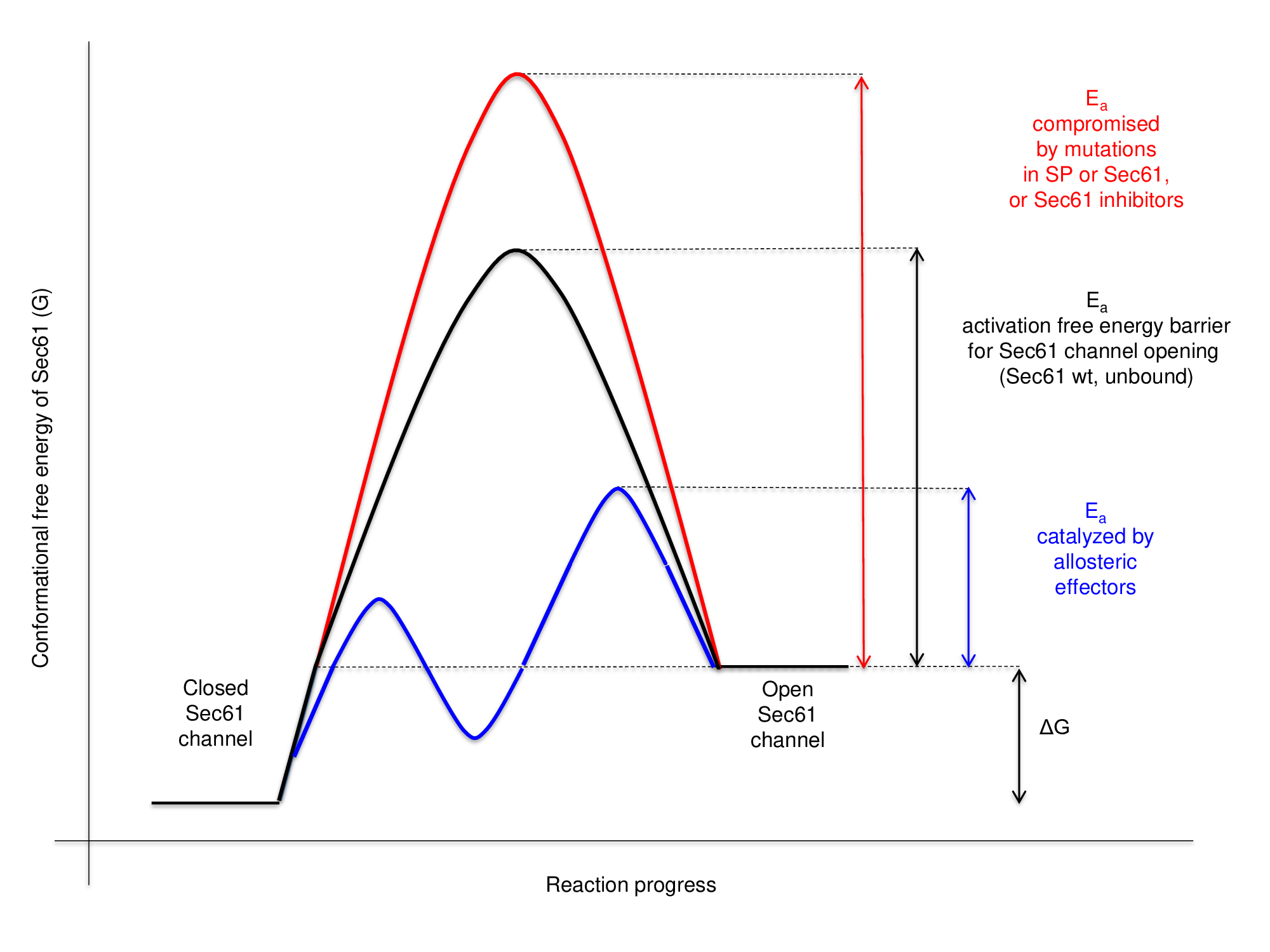

On the basis of the findings described above, we favour discussing the effects of the allosteric Sec61-channel effectors in terms of a free energy diagram (Figure 5). Accordingly, full Sec61-channel opening requires activation energy. The consecutive interactions of the H-region with the hydrophobic patch and the phospholipid bilayer lead to isosteric energy input and, therefore, lower the activation energy. When this is not sufficient, the Sec62/Sec63 +/- BiP-interactions with the Sec61-channel have to provide additional –in this case allosteric- energy input, thereby accelerating the conformational changes of the channel or increasing the affinity for the transport substrate [47][47]. Alternatively or additionally, the allosteric effectors may affect the equilibrium between the closed and open channel conformations. Notably, the same cluster of positively charged residues within proapelin that determines BiP-dependence was found to be responsible for the sensitivity of ppa import towards cyclic heptadepsipeptide inhibitors of the Sec61-channel, such as CAM741 (Figure 4) [47][47][64][65]. Replacement of this cluster by alanines relieves both BiP-dependence and CAM-741-sensitivity. Therefore, we favour the idea that the energetic barrier or activation energy for Sec61-channel opening is raised by cyclic heptadepsipeptide inhibitors, such as CAM741. Interestingly, cotranslational ER-import of the ERj3 precursor protein is also CAM741-sensitive due to the cluster of positive charges within the mature region[56].

Figure 5. I Energy diagram for Sec61-channel gating. Complete BiP-depletion and Sec61 inhibition by small molecules both prevent productive insertion of ppa into the Sec61-channel, i.e. opening of the channel. Notably, SEC61A1-mutations can also increase the energy barrier for channel opening either directly (V85D or V67G mutation)[70] or indirectly, such as by interfering with BiP binding (Y344H mutation) [43][47][43][47]. See text for details.

Figure 5. I Energy diagram for Sec61-channel gating. Complete BiP-depletion and Sec61 inhibition by small molecules both prevent productive insertion of ppa into the Sec61-channel, i.e. opening of the channel. Notably, SEC61A1-mutations can also increase the energy barrier for channel opening either directly (V85D or V67G mutation)[70] or indirectly, such as by interfering with BiP binding (Y344H mutation) [43][47][43][47]. See text for details.

So far, there are no structural data on the mammalian Sec62/Sec63-complex. However, the recent structural analysis of the yeast heptameric SEC-complex elucidated extensive interactions between Sec63 and the Sec61 complex including contacts in their cytosolic, membrane and luminal domains, which is perfectly in line with the above-discussed intrinsic Sec63 activity in ER-import of ps [47][47]. Notably, the yeast SEC-complex includes in addition to the heterotrimeric Sec61 complex and the heterodimeric Sec62/Sec63 complex the heterodimeric Sec71/Sec72-complex and is supposedly involved only in posttranslational protein import into the ER. Of further note, the additional components, Sec71 and Sec72, are without known mammalian orthologs [39][40][41][39][40][41]. According to the structure of the yeast SEC-complex, the cytosolic Brl domain of Sec63 interacts with cytosolic loops 6 and 8 of Sec61α. In the membrane, Sec63 (transmembrane helix 3) contacts all three subunits of the Sec61 complex in the hinge region opposite of the lateral gate, including transmembrane helices 1 and 5 of Sec61α as well the tail-anchors of Sec61β and Sec61γ. In addition, the short luminal N-terminus of Sec63 appears to intercalate on the luminal side of the channel between the hinge loop (Sec61α loop 5) and Sec61γ. Thus, interactions of allosteric Sec61-channel effectors other than the ribosome with ER-luminal loops of Sec61a appear to be a common principle for their action.

Undoubtedly, gating of the Sec61-channel to the closed state, i.e. efficient and fast closing of the channel, also requires activation energy [43][43]. This is of particular importance for mammalian cells, where the ER serves as the main intracellular Ca2+ reservoir. In light of the energy diagram for Sec61-channel gating, it may not come as a surprise that BiP can also accelerate channel closure. Apparently, it supports the involved conformational change by interaction with the same ER-luminal loop 7 of Sec61α, which is involved in channel opening [43][43]. However, it does so in collaboration with a possible dimer of two ER-luminal Hsp40 co-chaperones, ERj3 and ERj6[66].

6. What Defines Inefficiently Gating SPs of a Small Human Presecretory Proteins?

-

What defines inefficiently gating SPs of a small human presecretory proteins?

Among the low performing precursor proteins -small or large- we found two different types of SPs, those with low overall hydrophobicity in combination with high glycine- plus proline-content and those with low H-region hydrophobicity in combination with detrimental features within the mature part[56][58]. In both cases, full Sec61-channel opening in cotranslational transport is supported by allosteric Sec61-channel effectors, the TRAP-complex or the Sec62/Sec63-complex in collaboration with or without BiP[55][56][58]. Notably, lower SP hydrophobicity has also been found to be decisive for Sec62p/Sec63p-involvement in posttranslational ER-import in yeast. Based on the fact that all so far-analyzed small human presecretory proteins showed a requirement for Sec62 [44][47][44,47], we had a closer look at the SP of small human presecretory proteins with respect to overall hydrophobicity, delta Gpred, glycine- plus proline-content, N-region net charge, H-region hydrophobicity, and C-region polarity, as previously done for TRAP clients[58]. Strikingly, higher than average overall hydrophobicity and higher than average H-region hydrophobicity appear to define inefficiently gating SPs in the context of small precursor proteins, which is in sharp contrast to the SPs of precursor polypeptides in cotranslational and ribosome-dependent transport mentioned above[53]. Therefore, the question is how these apparently contradictory findings can be reconciled. We hypothesize that both higher and lower than average SP hydrophobicity may extend the sampling or dwell time of the SP in the Sec61-channel, simply because the interactions with the hydrophobic patch are either too strong, i.e. disfavouring reversibility, or not strong enough to trigger spontaneous opening of the lateral gate and accompanying full channel opening, which obviously remains to be experimentally tested. Therefore, allosteric effectors of the channel have to come into play, in particular when aberrant hydrophobicity coincides with low SP helix propensity (as in the case of TRAP action)[58] or with deleterious features downstream of the SP in the mature region (as in the case of Sec62 and Sec63 action) [47][47][55][56]. Interestingly, there appear to be some cotranslationally translocated precursors polypeptides, which can involve Sec61-channel gating by either the TRAP or the Sec62/Sec63-complex[56][58] . Thus, there is a certain redundancy in ER protein import at the level of Sec61-channel gating, too. However, this does not seem to extend to the posttranslational import of small presecretory proteins, which may be related to the fact that the SP of the latter lack the tendency towards a high glycine- and proline-content that characterizes the SPs of TRAP-dependent precursors[58].

In contrast, the mature region of small presecretory proteins might comprise deleterious clusters of positive charges, as they represent sites for their processing into several biologically active peptides. The role of BiP in compensating their presence can thus be seen in the context of an inherent disability of the Sec61-channel to translocate protein regions with the respective features. We note that such deficiency might only be apparent when clusters of positive charges are implemented in the mature region i) with additional structural features (intrinsically disordered domains, see ppa and prion protein), or ii) at a specific location or distance to the SP, or iii) at a certain frequency and defined distances (reflecting the sizes of the bioactive peptides after maturation).

7. What is the Point of Having Small Presecretory Proteins?

-

What is the point of having small presecretory proteins?

One can rephrase this question into the following ones, i) what is the advantage of having small and large precursor polypeptide, ii) what is the advantage of having efficiently and inefficiently gating SPs, iii) what is the advantage of having precursor polypeptides, which do or don´t depend on allosteric Sec61-channel effectors. We are convinced that the answer to all these questions was given in the course of evolution and is related to differential regulation of both ER-targeting and import of precursor polypeptides into the ER. When certain precursors, such as the ones larger than 100 amino acid residues, have a preference for the SRP-/SR-system their ER-import can be regulated independently of ER-import of small presecretory proteins, which use SRP-independent pathways. On the other hand, when certain precursor polypeptides, such as at least some of the small ones, depend on Ca2+-calmodulin, their import -in contrast to the SRP-/SR-dependent one- can be regulated in a Ca2+-dependent fashion [42][50][42,50]. Furthermore, when certain precursor proteins depend on allosteric Sec61-channel effectors, such as the Sec62/Sec63-complex, their ER-import can be regulated independently of the import of the Sec62/Sec63-independent precursors. The same can be said about the TRAP-complex. Notably, both the TRAP- and the Sec62/Sec63-complex are subject to phosphorylation and to Ca2+-binding[67,68,69]. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that these two modifications play an important and possibly even reciprocal regulatory role in ER protein import, an area, which has not yet been explored at all. To give just two potential examples: Calreticulin has a dual intracellular location, in the nucleus and the ER-lumen, and depends on the TRAP-complex in its ER-import[58]. The ER-luminal co-chaperone ERj6 has been described to be a player in both cytosolic and ER-luminal protein quality control in ER protein import and appears to involve Sec62 and Sec63 in its import. We hypothesize that in both cases phosphorylation and/or Ca2+-binding to the allosteric Sec61-channel effectors may favour the one or the other of the two possible intracellular locations. These kinds of regulatory mechanisms may well be involved in the course of cell differentiation or specific cellular demands and certain conditions, such as stress.

References

- Blobel G and Dobberstein B (1975) Transfer of proteins across membranes. I. Presence of proteolytically processed and unprocessed nascent immunoglobulin light chains on membrane-bound ribosomes of murine myeloma. J Cell Biol 67, 835–851. 1. Palade, G. Intracellular aspects of protein synthesis. Science 1975, 189, 347-358.2. Blobel, G.; Dobberstein, B. Transfer of proteins across membranes: I. Presence of proteolytically processed and unprocessed nascent immunoglobulin light chains on membrane-bound ribosomes of murine myeloma. J. Cell Biol. 1975, 67, 835-851.3. Blobel, G.; Dobberstein, B. Transfer of proteins across membranes: II. Reconstitution of functional rough microsomes from heterologous components. J. Cell Biol. 1975, 67, 852-862.4. Lang, S.; Nguyen, D.; Bhadra, P.; Jung, M.; Helms, V.; Zimmermann, R. Signal peptide features determining the substrate specificities of targeting and translocation components in human ER protein import. Front. Physiol., 2022, 13, 833540.5. Aviram, N.; Schuldiner, M. Targeting and translocation of proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 4079-4085.6. Walter, P.; Ibrahimi, I.; Blobel, G. Translocation of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum, I. Signal recognition protein (SRP) binds to in-vitro-assembled polysomes synthesizing secretory protein. J. Cell Biol. 1981, 91, 545-550.7. Walter, P.; Blobel, G. Translocation of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum. II. Signal recognition protein (SRP) mediates the selective binding to microsomal membranes of in-vitro-assembled polysomes synthesizing secretory protein. J. Cell Biol. 1981, 91, 551-556.8. Siegel, V.; Walter, P. The affinity of signal recognition particle for presecretory proteins is dependent on nascent chain length. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 1769-1775.9. Noriega, T.R.; Tsai, A.; Elvekrog, M.M.; Petrov, A.; Neher, S.B.; Chen, J.; Bradshaw, N.; Puglisi, J.D.; Walter, P. Signal recognition particle-ribosome binding is sensitive to nascent chain length. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 19294-19305.10. Meyer, D.I.; Dobberstein, B. A membrane component essential for vectorial translocation of nascent proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum: requirements for its extraction and reassociation with the membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1980, 87, 498-502.11. Meyer, D.I.; Dobberstein, B. Identification and characterization of a membrane component essential for the translocation of nascent proteins across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 1980, 87, 503-508.12. Gilmore, R.; Blobel, G.; Walter, P. Protein translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum. I. Detection in the microsomal membrane of a receptor for the signal recognition particle. J. Cell Biol. 1982, 95, 463-469.13. Miller, J.D.; Tajima, S.; Lauffer, L.; Walter, P. The beta subunit of the signal recognition particle receptor is a transmembrane GTPase that anchors the alpha subunit, a peripheral membrane GTPase, to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 128, 273-282.14. Abell, B.M.; Pool, M.R.; Schlenker, O.; Sinning, I.; High, S. Signal recognition particle mediates post-translational targeting in eukaryotes. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2755-2764.15. Simon, S.M.; Blobel, G. A protein-conducting channel in the endoplasmic reticulum, Cell 1991, 65, 371-380.16. Görlich, D.; Prehn, S.; Hartmann, E.; Kalies, K.-U.; Rapoport, T.A. A mammalian homolog of SEC61p and SECYp is associated with ribosomes and nascent polypeptides during translocation. Cell 1992, 71, 489-503.17. Görlich, D.; Rapoport, T.A. Protein translocation into proteoliposomes reconstituted from purified components of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Cell 1993, 75, 615-630.18. Wirth, A.; Jung, M.; Bies, C.; Frien, M.; Tyedmers, J.; Zimmermann, R.; Wagner, R. The Sec61p complex is a dynamic precursor activated channel. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 261-268.19. van den Berg, B.; Clemons, W.M.; Collinson, I.; Modis, Y.; Hartmann, E.; Harrison, S.C.; Rapoport, T.A. X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel, Nature 2004, 427, 36-44.20. Pfeffer, S.; Brandt, F.; Hrabe, T.; Lang, S.; Eibauer, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Förster, F. Structure and 3D arrangement of ER-membrane associated ribosomes. Structure 2012, 20, 1508-1518.21. Pfeffer, S.; Dudek, J.; Gogala, M.; Schorr, S.; Linxweiler, J.; Lang, S.; Becker, T.; Beckmann, R.; Zimmermann, R.; Förster, F. Structure of the mammalian oligosaccharyltransferase in the native ER protein translocon. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3072. 22. Pfeffer, S., Burbaum, L., Unverdorben, P., Pech, M., Chen, Y., Zimmermann, R., Beckmann, R., Förster, F. Structure of the native Sec61 protein-conducting channel. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8403.23. Voorhees, R.M.; Hegde R S Structure of the Sec61 channel opened by a signal peptide. Science 2016, 351, 88-91.24. Pfeffer, S., Dudek, J., Zimmermann, R. & Förster, F. Organization of the native ribosome-translocon complex at the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 2122-2129.25. Pfeffer, S.; Dudek, J.; Ng, B.; Schaffa, M.; Albert, S.; Plitzko, J.; Baumeister, W.; Zimmermann, R.; Freeze, H.; Engel, B.D.; Förster, F. Dissecting the molecular organization of the translocon-associated protein complex. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14516.26. Liaci, A.M.; Steigenberger, B.; Tamara, S.; de Souza, P.T.; Gröllers-Mulderij, M.; Ogrissek, P.; Marrink, S.-J.; Scheltema, R.A.; Förster, F. Structure of the human signal peptidase complex reveals the determinants for signal peptide cleavage. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3934-3948.27. Watts, C.; Wickner, W.; Zimmermann, R. M13 procoat protein and preimmunoglobulin share processing specificity but use different membrane receptor mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 2809-2813.28. Zimmermann, R.; Mollay, C. Import of honeybee prepromelittin into the endoplasmic reticulum: Requirements for membrane insertion, processing and sequestration. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 12889-12895.29. Schlenstedt, G.; Zimmermann, R. Import of frog prepropeptide GLa into microsomes requires ATP but does not involve docking protein or ribosomes. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 699-703.30. Müller, G.; Zimmermann, R. Import of honeybee prepromelittin into the endoplasmic reticulum: Structural basis for independence of SRP and docking protein. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 2099-2107.31. Wiech, H.; Sagstetter, M.; Müller, G.; Zimmermann, R. The ATP requiring step in the assembly of M 13 procoat protein into microsomes is related to preservation of transport competence of the precursor protein. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 1011-1016.32. Müller, G.; Zimmermann, R. Import of honeybee prepromelittin into the endoplasmic reticulum: Energy requirements for membrane insertion. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 639-648.33. Zimmermann, R.; Sagstetter, M.; Lewis, M.J.; Pelham, HRB. Seventy-kilodalton heat shock proteins and an additional component from reticulocyte lysate stimulate import of M 13 procoat protein into microsomes. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 2875-2880.34. Schlenstedt, G.; Gudmundsson, G.H.; Boman, H.G; Zimmermann, R. A large presecretory protein translocates both cotranslationally, using signal recognition particle and ribosome, and posttranslationally, without these ribonucleoparticles, when synthesized in the presence of mammalian microsomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 13960-13968.35. Klappa, P.; Mayinger, P.; Pipkorn, R.; Zimmermann, M.; Zimmermann, R. A microsomal protein is involved in ATP-dependent transport of presecretory proteins into mammalian microsomes. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 2795-2803.36. Klappa, P.; Freedman, R.; Zimmermann, R. Protein disulfide isomerase and a lumenal cyclophilin-type peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerase are in transient contact with secretory proteins during late stages of translocation. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 232, 755-764.37. Dierks, T.; Volkmer, J.; Schlenstedt, G.; Jung, C.; Sandholzer, U.; Zachmann, K.; Schlotterhose, P.; Neifer, K.; Schmidt, B.; Zimmermann, R. A microsomal ATP-binding protein involved in efficient protein transport into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 6931-6942.38. Tyedmers, J.; Lerner, M.; Bies, C.; Dudek, J.; Skowronek, M.H.; Haas, I.G.; Heim, N.; Nastainczyk, W.; Volkmer, J.; Zimmermann, R. Homologs of the yeast Sec complex subunits Sec62p and Sec63p are abundant proteins in dog pancreas microsomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7214-7219.39. Mayer, H.-A.; Grau, H.; Kraft, R.; Prehn, S.; Kalies, K.-U., Hartmann, E. Mammalian Sec61 is associated with Sec62 and Sec63. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 14550-14557.40. Tyedmers, J.; Lerner, M.; Wiedmann, M.; Volkmer, J.; Zimmermann, R. Polypeptide chain binding proteins mediate completion of cotranslational protein translocation into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO Rep. 2005, 4, 505-510.41. Müller, L.; Diaz de Escauriaza, M.; Lajoie, P.; Theis, M.; Jung, M.; Müller, A.; Burgard, C.; Greiner, M.; Snapp, E.L.; Dudek, J.; Zimmermann, R. Evolutionary gain of function of the ER membrane protein Sec62 from yeast to humans. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 691-703.42. Shao, S.; Hegde, R.S. A calmodulin-dependent translocation pathway for small secretory proteins. Cell 2011, 147, 1576-1588.43. Schäuble, N.; Lang, S.; Jung, M.; Cappel, S.; Schorr, S.; Ulucan, Ö.; Linxweiler, J.; Dudek., J.; Blum, R.; Helms, V., Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; Cavalié, A.; Zimmermann, R. BiP-mediated closing of the Sec61 channel limits Ca2+ leakage from the ER. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3282-3296.44. Lakkaraju, A.K.K.; Thankappan, R.; Mary, C.; Garrison, J.L.; Taunton, J.; Strub, K. Efficient secretion of small proteins in mammalian cells relies on Sec62-dependent posttranslational translocation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 2712-2722.45. Lang, S.; Benedix, J.; Fedeles, S.V.; Schorr, S.; Schirra, C.; Schäuble, N.; Jalal, C.; Greiner, M.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Tatzelt, J.; Kreutzer, B.; Edelmann, L.; Krause, E.; Rettig, J.; Somlo, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Dudek, J. Different effects of Sec61a-, Sec62 and Sec63-depletion on transport of polypeptides into the endoplasmic reticulum of mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 1958-1969.46. Johnson, N.; Vilardi, F.; Lang, S.; Leznicki, P.; Zimmermann, R.; High, S. TRC-40 can deliver short secretory proteins to the Sec61 translocon. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 3612-3620.47. Haßdenteufel, S.; Johnson, N.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; High, S.; Zimmermann, R. Chaperone-mediated Sec61 channel gating during ER import of small precursor proteins overcomes Sec61 inhibitor-reinforced energy barrier. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1373-1386. 48. Haßdenteufel, S.; Nguyen, D.; Helms, V.; Lang, S.; Zimmermann, R. Components and mechanisms for ER import of small human presecretory proteins. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 2506-2524. 49. Johnson, N.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Theis, M.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; Zimmermann, R.; High, S. The signal sequence influences post-translational ER translocation at distinct stages. PLOSone 2013, 0075394.50. Haßdenteufel, S.; Schäuble, N.; Cassella, P.; Leznicki, P.; Müller, A.; High, S.; Jung, M.; Zimmermann, R. Calcium-calmodulin inhibits tail-anchored protein insertion into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum membrane. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 3485-3490.51. Casson, J.; McKenna, M.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Aviram, N.; Zimmermann, R., High, S. Multiple pathways facilitate the biogenesis of mammalian tail-anchored proteins. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 3851-3861.52. Aviram, N.; Ast, T.; Costa, E.A.; Arakel, E.; Chuartzman, S.G.; Jan, C.H.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Dudek, J.; Jung, M.; Schorr, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Schwappach, B.; Weissman, J.S.; Schuldiner, M. The SND proteins constitute an alternative targeting route to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 2016, 540, 134-138.53. Haßdenteufel, S.; Sicking, M.; Schorr, S.; Aviram, N.; Fecher-Trost, C.; Schuldiner, M.; Jung, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S. hSnd2 protein represents an alternative targeting factor to the endoplasmic reticulum in human cells. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 3211-3224.54. Tirincsi, A.; O´Keefe, S.; Nguyen, D.; Sicking, M.; Dudek, J.; Förster, F.; Jung, M.; Hadzibeganovic, D.; Helms, V.; High, S.; Zimmermann, R. Lang, S. Proteomics identifies substrates and a novel component in hSnd2-dependent ER protein targeting. Cells 2022, 11, 2925.55. Ziska, A.; Tatzelt, J.; Dudek, J.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; Zimmermann, R.; Haßdenteufel, S. The signal peptide plus a cluster of positive charges in prion protein dictate chaperone-mediated Sec61-channel gating. Biol. Open 2019, 8, bio040691.56. Schorr, S.; Nguyen, D.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Nagaraj, N.; Cavalié, A.; Greiner, M.; Weissgerber, P.; Loi, M.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; Molinari, M.; Förster, F.; Dudek, J.; Lang, S.; Helms, V.; Zimmermann R. Proteomics identifies signal peptide features determining the substrate specificity in human Sec62/Sec63-dependent ER protein import. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 4612-4640.57. Gamayun, I.; 0´Keefe, S.; Pick, T.; Klein, M.-C.; Nguyen, D.; McKibbin, C.; Piacenti, M.; Williams, H.M.; Flitch, S.L.; Whitehead, R.C.; Swanton, L.; Helms, V.; High, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Cavalié, A. Eeyarestatin compounds selectively enhance Sec61-mediated Ca2+ leakage from the endoplasmic reticulum Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 571-583.58. Nguyen, D.; Stutz, R.; Schorr, S.; Lang, S.; Pfeffer, S.; Freeze, H.F.; Förster, F.; Helms, V.; Dudek, J.; Zimmermann, R. Proteomics reveals signal peptide features determining the client specificity in human TRAP-dependent ER protein import. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 37639.59. Klein, M.-C.; Zimmermann, K.; Schorr, S.; Landini, M.; Klemens, P.A.W.; Altensell, J.; Jung, M.; Krause, E.; Nguyen, D.; Helms, V.; Rettig, J.; Fecher-Trost, C.; Cavalié, A.; Hoth, M.; Bogeski, I.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S.; Haferkamp, I. AXER is an ATP/ADP exchanger in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3489.60. Aviram, N.; Ast, T.; Costa, E.A.; Arakel, E.; Chuartzman, S.G.; Jan, C.H.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Dudek, J.; Jung, M.; Schorr, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Schwappach, B.; Weissman, J.S.; Schuldiner, M. The SND proteins constitute an alternative targeting route to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 2016, 540, 134-138.61. Haßdenteufel, S.; Sicking, M.; Schorr, S.; Aviram, N.; Fecher-Trost, C.; Schuldiner, M.; Jung, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S. hSnd2 protein represents an alternative targeting factor to the endoplasmic reticulum in human cells. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 3211-3224.62. Tirincsi, A.; O´Keefe, S.; Nguyen, D.; Sicking, M.; Dudek, J.; Förster, F.; Jung, M.; Hadzibeganovic, D.; Helms, V.; High, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S. Proteomics identifies substrates and a novel component in hSnd2-dependent ER protein targeting. Cells 2022, 11, 2925.63. Zimmermann, R. Rules of engagement for components of membrane protein biogenesis at the human ER. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8823. Special Issue on „Functional Proteomics: Insights from Biomedical Applications and Beyond”. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms2618882364. Garrison, J.L.; Kunkel, E.J.; Hegde, R.S.; J. Taunton, J. A substrate-specific inhibitor of protein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 2005, 436, 285-289.65. Besemer, J.; Harent, H.; Wang, S.; Oberhauser, B.; Marquardt, K.; Foster, C.A.; Schreiner, E.P.; de Vries, J.E.; Dascher-Nadel, C.; Lindley, I.J.D. Selective inhibition of cotranslational translocation of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Nature 2005, 436 290-293.66. Schorr, S.; Klein, M.-C.; Gamayun, I.; Melnyk, A.; Jung, M.; Schäuble, N.; Wang, Q.; Hemmis, B.; Bochen, F.; Greiner, M.; Lampel, P.; Urban, S.K.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Dudek, J.; Chen, X.-Z.; Wagner, R.; Cavalié, A.; Zimmermann, R. Co-chaperone specificity in gating of the polypeptide conducting channel in the membrane of the human endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18621-18635.67. Wada, I.; Rindress, D.; Cameron, P.H.; Ou, W.-J.; Doherty, J.J.II.; Louvard, D.; Bell, A.W.; Dignard, D.; Thomas, D.Y.; Bergeron, J.J.M. SSRa and associated calnexin are major calcium binding proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 19599-19610.68. Ampofo, E.; Welker, S.; Jung, M.; Müller, L.; Greiner, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Montenarh, M. CK2 phosphorylation of human Sec63 regulates its interaction with Sec62. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 2938-2945.69. Linxweiler, M.; Schorr, S.; Jung, M.; Schäuble, N.; Linxweiler, J.; Langer, F.; Schäfers, H.-J.; Cavalié, A.; Zimmermann, R.; Greiner, M. Targeting cell migration and the ER stress response with calmodulin antagonists: A clinically tested small molecule phenocopy of SEC62 gene silencing in human tumor cells. BMC – cancer 2013, 13, 574.70. Schubert, D.; Klein, M.-C.; Haßdenteufel, S.; Caballero-Oteyza, A.; Yang, L.; Proietti, M.; Bulashevska, A.; Kemming, J.; Kühn, J.; Winzer, S.; Rusch, S.; Fliegauf, M.; Schäffer, A.A.; Pfeffer, S.; Geiger, R.; Cavalié, A.; Cao, H.; Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Rizzi, M.; Eibel, H.; Kobbe, R.; Marks, A.; Peppers, B.P.; Hostoffer, R.W.; Puck, J.M.; Zimmermann, R.; Grimbacher, B. Plasma cell deficiency in human subjects with heterozygous mutations in Sec61 translocon alpha 1 (SEC61A1). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 1427-1438.

- Blobel G and Dobberstein B (1975) Transfer of proteins across membranes. II. Reconstitution of functional rough microsomes from heterologous components. J Cell Biol 67, 852–862.

- Gilmore R, Blobel G and Walter P (1982) Protein translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum. I. Detection in the microsomal membrane of a receptor for the signal recognition particle. J Cell Biol 95, 463–469.

- Gilmore R, Walter P and Blobel G (1982) Protein translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum. II. Isolation and characterization of the signal recognition particle receptor. J Cell Biol 95, 470–477.

- Blobel G (1980) Intracellular protein topogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77, 1496–1500.

- Walter P and Blobel G (1980) Purification of a membrane-associated protein complex required for protein translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77, 7112–7116.

- Voorhees RM and Hegde RS (2015) Structures of the scanning and engaged states of the mammalian SRP-ribosome complex. eLife 4, e07975.

- Halic M and Beckmann R (2005) The signal recognition particle and its interactions during protein targeting. Curr Opin Struct Biol 15, 116–125.

- Egea PF, Shan SO, Napetschnig J, Savage DF, Walter P and Stroud RM (2004) Substrate twinning activates the signal recognition particle and its receptor. Nature 427, 215–221.

- Halic M, Becker T, Pool MR, Spahn CM, Grassucci RA, Frank J and Beckmann R (2004) Structure of the signal recognition particle interacting with the elongation-arrested ribosome. Nature 427, 808–814.

- Bohnsack MT and Schleiff E (2010) The evolution of protein targeting and translocation systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1803, 1115–1130.

- Yabal M, Brambillasca S, Soffientini P, Pedrazzini E, Borgese N and Makarow M (2003) Translocation of the C terminus of a tail-anchored protein across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane in yeast mutants defective in signal peptide-driven translocation. J Biol Chem 278, 3489–3496.

- Shao S and Hegde RS (2011) A calmodulin-dependent translocation pathway for small secretory proteins. Cell 147, 1576–1588.

- Schlenstedt G, Gudmundsson GH, Boman HG and Zimmermann R (1990) A large presecretory protein translocates both cotranslationally, using signal recognition particle and ribosome, and posttranslationally, without these ribonucleoparticles, when synthesized in the presence of mammalian microsomes. J Biol Chem 265, 13960–13968.

- Ast T, Cohen G and Schuldiner M (2013) A network of cytosolic factors targets SRP-independent proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 152, 1134–1145.

- Hann BC and Walter P (1991) The signal recognition particle in S. cerevisiae. Cell 67, 131–144.

- Kutay U, Hartmann E and Rapoport TA (1993) A class of membrane proteins with a C-terminal anchor. Trends Cell Biol 3, 72–75.

- Schuldiner M, Metz J, Schmid V, Denic V, Rakwalska M, Schmitt HD, Schwappach B and Weissman JS (2008) The GET complex mediates insertion of tail-anchored proteins into the ER membrane. Cell 134, 634–645.

- Stefanovic S and Hegde RS (2007) Identification of a targeting factor for posttranslational membrane protein insertion into the ER. Cell 128, 1147–1159.

- Vilardi F, Lorenz H and Dobberstein B (2011) WRB is the receptor for TRC40/Asna1-mediated insertion of tail-anchored proteins into the ER membrane. J Cell Sci 124, 1301–1307.

- Yamamoto Y and Sakisaka T (2012) Molecular machinery for insertion of tail-anchored membrane proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane in mammalian cells. Mol Cell 48, 387–397.

- Aviram N, Ast T, Costa EA, Arakel EC, Chuartzman SG, Jan CH, Haßdenteufel S, Dudek J, Jung M, Schorr S et al (2016) The SND proteins constitute an alternative targeting route to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 540, 134–138.

- Zhao Y, Hu J, Miao G, Qu L, Wang Z, Li G, Lv P, Ma D and Chen Y (2013) Transmembrane protein 208: a novel ER-localized protein that regulates autophagy and ER stress. PLoS One 8, e64228.

- Lang S, Benedix J, Fedeles SV, Schorr S, Schirra C, Schäuble N, Jalal C, Greiner M, Haßdenteufel S, Tatzelt J et al. (2012) Different effects of Sec61α, Sec62 and Sec63 depletion on transport of polypeptides into the endoplasmic reticulum of mammalian cells. J Cell Sci 125, 1958–1969.

- Tyedmers J, Lerner M, Bies C, Dudek J, Skowronek MH, Haas IG, Heim N, Nastainczyk W, Volkmer J and Zimmermann R (2000) Homologs of the yeast Sec complex subunits Sec62p and Sec63p are abundant proteins in dog pancreas microsomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97, 7214–7219.

- Guth S, Volzing C, Müller A, Jung M and Zimmermann R (2004) Protein transport into canine pancreatic microsomes: a quantitative approach. Eur J Biochem 271, 3200–3207.

- Wilson R, Allen AJ, Oliver J, Brookman JL, High S and Bulleid NJ (1995) The translocation, folding, assembly and redox-dependent degradation of secretory and membrane proteins in semi-permeabilized mammalian cells. Biochem J 307, 679–687.

- Fecher-Trost C, Wissenbach U, Beck A, Schalkowsky P, Stoerger C, Doerr J, Dembek A, Simon-Thomas M, Weber A, Wollenberg P et al. (2013) The in vivo TRPV6 protein starts at a non-AUG triplet, decoded as methionine, upstream of canonical initiation at AUG. J Biol Chem 288, 16629–16644.

- Colombo SF, Cardani S, Maroli A, Vitiello A, Soffientini P, Crespi A, Bram RF, Benfante R and Borgese N (2016) Tail-anchored protein biogenesis in mammals: function and reciprocal interactions of the two subunits of the TRC40 receptor. J Biol Chem, 291, 15292–5306.

- Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, Ding H, Koh JL, Toufighi K, Mostafavi S et al. (2010) The genetic landscape of a cell. Science 327, 425–431.

- Costanzo M, VanderSluis B, Koch EN, Baryshnikova A, Pons C, Tan G, Wang W, Usaj M, Hanchard J, Lee SD et al. (2016) A global genetic interaction network maps a wiring diagram of cellular function. Science 353, aaf1420.

- Schuldiner M, Collins SR, Thompson NJ, Denic V, Bhamidipati A, Punna T, Ihmels J, Andrews B, Boone C, Greenblatt JF et al. (2005) Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell 123, 507–519.

- Pfeffer S, Dudek J, Zimmermann R and Förster F (2016) Organization of the native ribosome–translocon complex at the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta 1860, 2122–2129.

- Pfeffer S and Förster F (2016) Sec61: a static framework for membrane-protein insertion. Channels 10, 167–169.

- Pfeffer S, Brandt F, Hrabe T, Lang S, Eibauer M, Zimmermann R and Förster F (2012) Structure and 3D arrangement of endoplasmic reticulum membrane-associated ribosomes. Structure 20, 1508–1518.

- Pfeffer S, Burbaum L, Unverdorben P, Pech M, Chen Y, Zimmermann R, Beckmann R and Förster F (2015) Structure of the native Sec61 protein-conducting channel. Nat Commun 6, 8403. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9403.

- Dudek J, Pfeffer S, Lee P, Jung M, Cavalié A, Helms V, Förster F and Zimmermann R (2015) Protein transport into the human endoplasmic reticulum. J Mol Biol 427(Part A), 1159–1175.

- Pfeffer S, Dudek J, Schaffer M, Ng BG, Albert S, Plitzko JM, Baumeister W, Zimmermann R, Freeze HH, Engel BD et al. (2017) Dissecting the molecular organization of the translocon-associated protein complex. Nat Commun 8, 14516.

- Johnson N, Haßdenteufel S, Theis M, Paton AW, Paton JC, Zimmermann R and High S (2013) The signal sequence influences post-translational ER translocation at distinct stages. PLoS One 8, e75394.

- Abell BM, Pool MR, Schlenker O, Sinning I and High S (2004) Signal recognition particle mediates post-translational targeting in eukaryotes. EMBO J 23, 2755–2764.

- Schibich D, Gloge F, Pöhner I, Björkholm P, Wade RC, von Heijne G, Bukau B and Kramer G (2016) Global profiling of SRP interaction with nascent polypeptides. Nature 536 , 219–223.

- Akopian D, Shen K, Zhang X and Shan S (2013) Signal recognition particle: an essential protein-targeting machine. Annu Rev Biochem 82 , 693–721.

- Hainzl T, Huang S, Merilainen G, Brannstrom K and Sauer-Eriksson AE (2011) Structural basis of signal-sequence recognition by the signal recognition particle. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18 , 389–391.

- Pechmann S, Chartron JW and Frydman J (2014) Local slowdown of translation by nonoptimal codons promotes nascent-chain recognition by SRP in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21 , 1100–1105.

- Chartron JW, Hunt KCL and Frydman J (2016) Cotranslational signal-independent SRP preloading during membrane targeting. Nature 536 , 224–228.

- Haßdenteufel S, Schäuble N, Cassella P, Leznicki P, Müller A, High S, Jung M and Zimmermann R (2011) Ca2+-calmodulin inhibits tail-anchored protein insertion into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum membrane. FEBS Lett 585 , 3485–3490.

- Vogl C, Panou I, Yamanbaeva G, Wichmann C, Mangosing SJ, Vilardi F, Indzhykulian AA, Pangršič T, Santarelli R, Rodriguez-Ballesteros M et al. (2016) Tryptophan-rich basic protein (WRB) mediates insertion of the tail-anchored protein otoferlin and is required for hair cell exocytosis and hearing. EMBO J 35 , 2536–2552.

- Rivera-Monroy J, Musiol L, Unthan-Fechner K, Farkas Á, Clancy A, Coy-Vergara J, Weill U, Gockel S, Lin S, Corey DP et al. (2016) Mice lacking WRB reveal differential biogenesis requirements of tail-anchored proteins in vivo. Sci Rep 6, 39464.

- Norlin S, Parekh VS, Naredi P and Edlund H (2016) Asna1/TRC40 controls β-cell function and endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis by ensuring retrograde transport. Diabetes 65 , 110–119.

- Käll L, Krogh A and Sonnhammer ELL (2004) A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol 338 , 1027–1036.

- Fagerberg L, Jonasson K, von Heijne G, Uhlén M and Berglund L (2010) Prediction of the human membrane proteome. Proteomics 10 , 1141–1149.

- Wang FC (2014) The Get1/2 transmembrane complex is an endoplasmic-reticulum membrane protein insertase. Nature 512 , 441–444.