To fulfil its role in protein biogenesis, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) depends on the Hsp70 chaperone BiP that requires a constant ATP-supply. While the original biochemical approaches established hallmarks of the ATP transport into the ER, such as nucleotide selectivity, affinity, and antiport mode, the more recent live-cell imaging methods employing sensitive, localized molecular probes identified the low abundant ATP/ADP exchanger in the membrane of the human ER. Our screen of gene expression datasets for member(s) of the family of solute carriers that are co-expressed with BiP and are ER membrane proteins identified SLC35B1 as a potential candidate. Heterologous expression of SLC35B1 in E. coli revealed that SLC35B1 is highly specific for ATP and ADP and acts in antiport mode, two of four characteristics it shared with the ATP transport activity, which is present in rough ER membranes. Moreover, depletion of SLC35B1 from HeLa cells reduced ER ATP levels and, therefore, BiP activity, which implied that SLC35B1 mediates ATP uptake into the ER plus ADP release from the ER in vivo. Thus, human SLC35B1 provides ATP to the ER and was named ATP/ADP exchanger in the ER membrane or AXER. Furthermore, we characterized a regulatory circuit that is able to maintain the ATP supply in the ER ad hoc and was termed ER low energy response or lowER. Recent work by others confirmed the role and mode of action of AXER and also suggested a possible scenario for long term adjustments (termed CaATiER). Most recently, the structure of AXER was solved and allowed the deduction of its molecular mechanism. Thus, the dust has settled on the discovery of AXER.

- AXER, SLC35B1, ATP/ADP exchange between cytosol and ER

1. Introduction

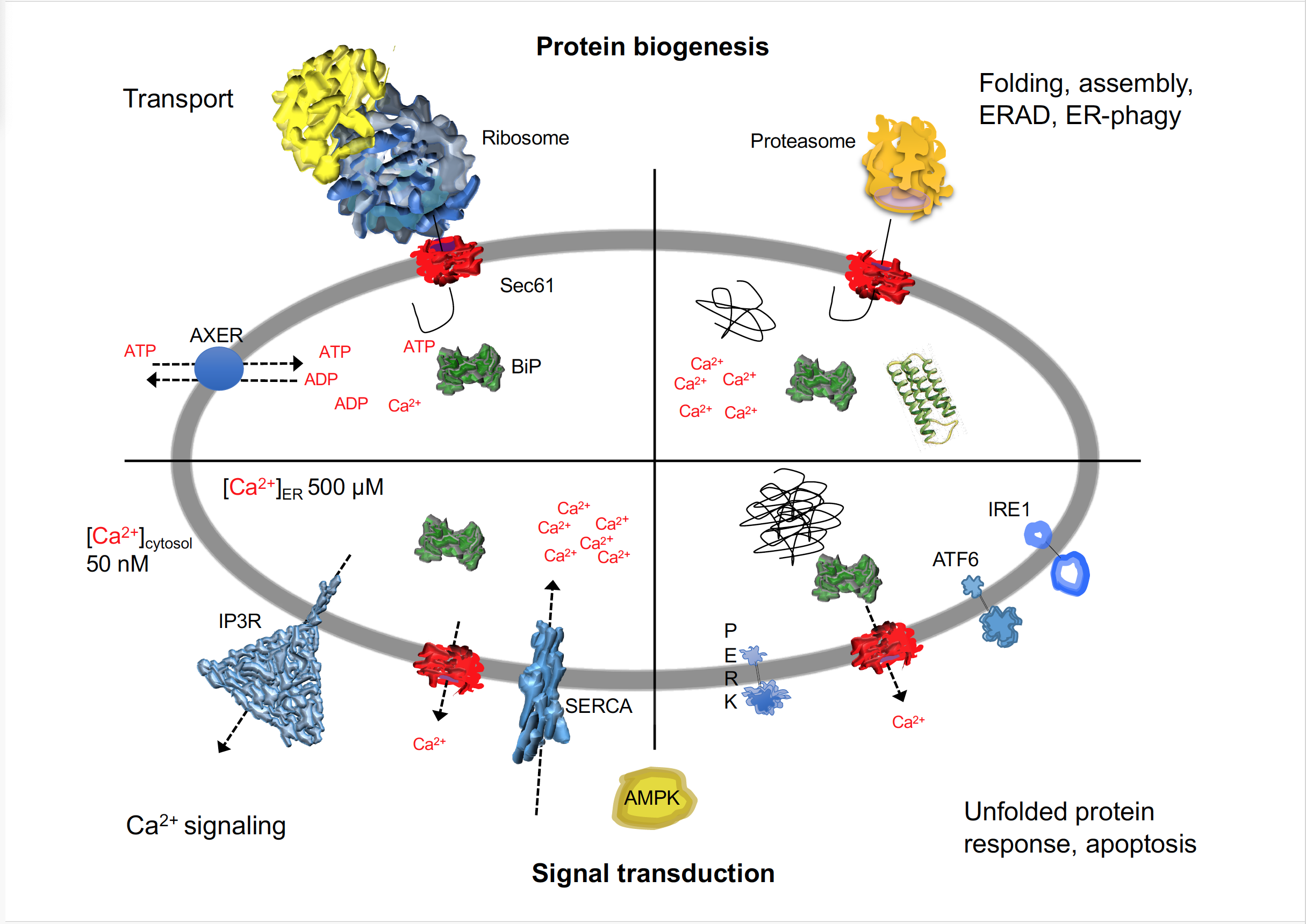

In order to play its central role in protein biogenesis, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of nucleated cells depends on an Hsp70-type molecular chaperone, termed immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (BiP) (FigureFigure 1) 1)[1][2][1][2] . BiP is present in the ER lumen in millimolar concentration and requires a constant supply of ATP for its various functions[3][4][5][6][7] [3][4][5][6][7]. Moreover, ATP hydrolysis by BiP generates ADP and, therefore, necessitates ADP removal from the ER.

Figure 1. I The human ER is a major site of protein biogenesis, signal transduction and calcium homeostasis. The cartoon depicts a schematic cross section through the ER and highlights the multiple roles of BiP and the Sec61 complex in protein biogenesis and signal transduction in human cells. AMPK, AMP-dependent protein kinase; ATF6, activating transcription factor 6; AXER, ATP/ADP exchanger of the ER membrane; ERAD, ER-associated protein degradation; IP3R, inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptor; IRE1; inositol-requiring enzyme 1; PERK, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase; SERCA, sarcoplasmic endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPases; UPR, unfolded protein response. See text for details.

Originally, classical biochemical approaches were employed in the putative identification and characterization of ATP carriers or ATP/ADP exchangers in the ER membrane. ATP import was reconstituted into proteoliposomes, harboring the total set of mammalian (rat liver, dog pancreas) or yeast ER membrane proteins, and this set of membrane proteins was subjected to purification of the transport activity by various standard methods. In none of these systems, however, did the biochemical approach identify the elusive carrier or exchanger[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] [8][9][10][11][12][13][14]. However, the approach established certain hallmarks for the transport activity, such as protein-mediation (i.e. saturable and sensitive to temperature, pronase, and inhibitors (i.e. DIDS, NEM)), nucleotide selectivity (i.e. specificity for ATP and ADP), high nucleotide affinity (i.e. low µM KM), antiport transport mode (i.e. requirement for nucleotide pre-loading of the proteoliposomes), and magnesium independence (i.e. insensitivity to EDTA). Next, ER membrane-resident ATP/ADP antiporters were identified with the help of genetic approaches in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana (ER-ANT1) and in the alga Phaeodactylum tricornutum (PtNTT5)[15][16] [15][16]. These proteins, however, do apparently not represent the major carriers for chemical energy in the ER of these organisms and do not have mammalian and yeast orthologs. Thus, until quite recently ubiquitous proteins catalyzing the ATP uptake and the concomitant ADP release at the ER membrane had remained unknown at the molecular level. Yet, recent work established a set of hallmarks for cell type-specific regulation of ATP homeostasis in the ER of HeLa and INS-1 cells[17] [17]. Accordingly, Ca2+-efflux from the ER into the cytosol is coupled to both increased ADP phosphorylation in the cytosol (dominant in HeLa cells) plus mitochondria (dominant in INS-1 cells) as well as increased ATP uptake into the ER by an at the time unknown ATP carrier in the ER membrane, which itself is stimulated by Ca2+-efflux from the ER into the cytosol. Furthermore, the cytosolic calcium- and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), the master regulator of energy metabolism with a link to the UPR[18][19] [18][19], is essential for increased ADP phosphorylation at least in HeLa cells[17] [17].

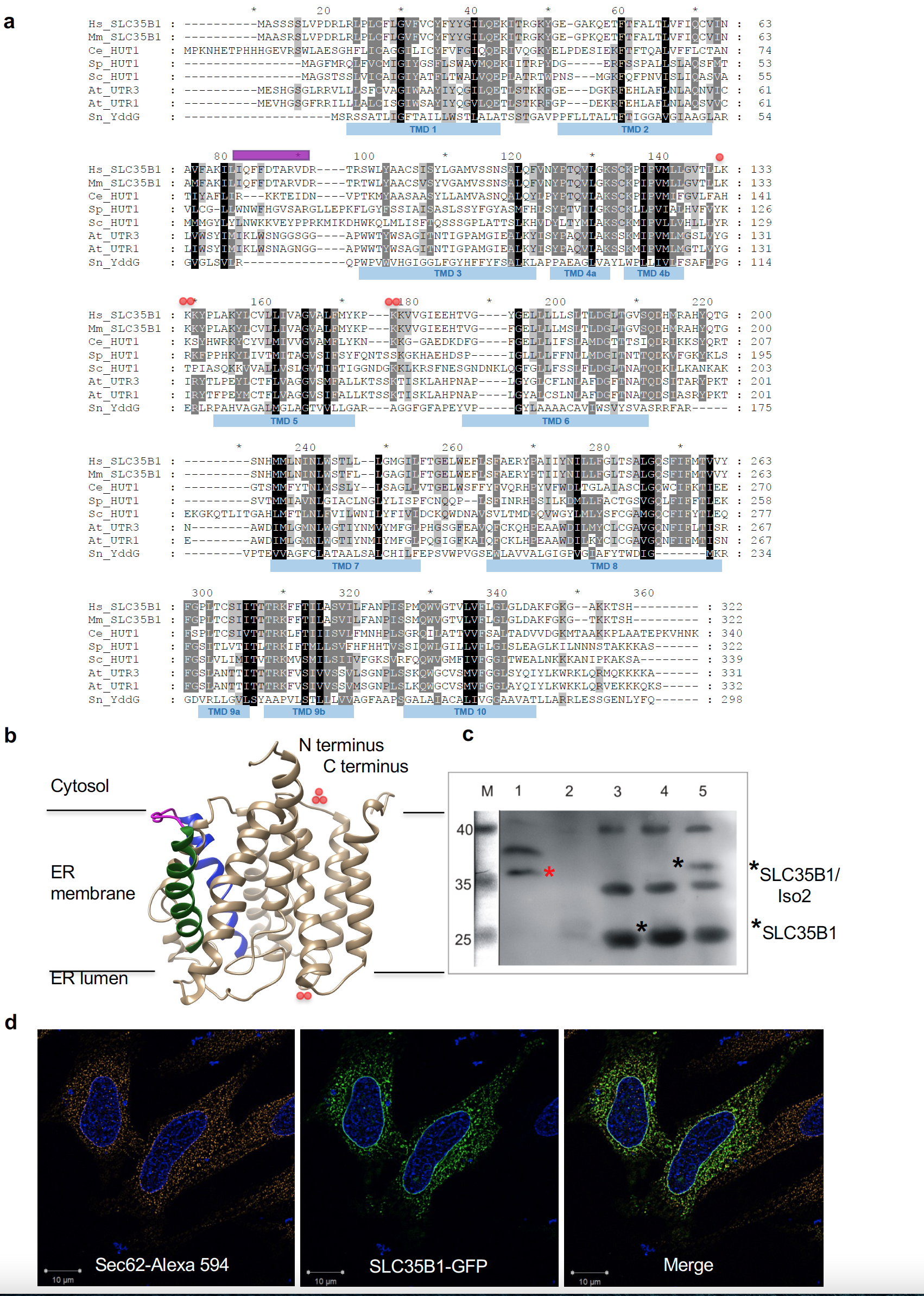

Screening databases for solute carriers (SLCs)[20][21] [20][21] that are located in the ER membrane (GeneCards: http://www.genecards.org, The Human Protein Atlas: https://www.proteinatlas.org) and that show the same expression pattern in human tissues as BiP (GenesLikeMe: https://glm.genecards.org/#input), drew our attention to SLC35B1 (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot: P78383.1). Human SLC35B1 has up to three different isoforms that are encoded by different mRNA variants (Figure 2a). It is a member of the nucleotide-sugar transporter family[22][23][24] [22][23][24] and orthologs are present in diverse eukaryotes, including plants. SLC35B1 was predicted to have ten transmembrane helices and to be structurally related to members of the drug/metabolite transporter (DMT) superfamily (FigureFigure 2b) 2b)[21][25][21][25].

Figure 2. | Putative structure and intracellular localization of SLC35B1. (a) Protein sequences are from UniProt or GeneBank and shown in single letter code for Homo sapiens (Hs, P78383.1; NM_005827.1), Mus musculus (Mm, P97858.1), Caenorhabditis elegans (Ce, CAC35849), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Sp, CAB46704.1), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc, CAA97965), Arabidopsis thaliana (At, At1g14360 and At2g02810), and Starkeya novella (YddG, gi:502932551). The sequences were aligned using ClustalX and GeneDoc. The amino and carboxy termini face the cyosol, the double lysine motif near the carboxy terminus of mammalian SLC35B1 serves as ER retention motif. The predicted IQ motif, unique to mammalian SLC35B1, is shown in purple, positively charged clusters in red. SLC35B1/Isoform 2 comprises an amino-terminal extension of 37 amino acids (MRPLPPVGDVRLWTSPPPPLLPVPVVSGSPVGSSGRL) (NM_005827.2), in transcript variant 2 (NM_001278784.1) the first 78 amino acids, including two N-terminal transmembrane helices, of SLC35B1 are replaced by the oligopeptide: mcdqccvcqdL. (b) Hypothetical structural model of human SLC35B1, as predicted by the Phyre2 server[27] [26][27]. Transmembrane helices 2 (green) plus 3 (blue) and the connecting loop (purple) with the putative IQ motif are highlighted, as are clusters of positively charged amino acid residues (red). (c) A 4% digitonin extract of canine pancreatic rough microsomal membrane proteins (derived from 6 mg microsomal protein) was subjected to SDS-PAGE in parallel to E. coli membranes (25 µg protein), which were derived from non-transfected and SLC35B1- or SLC35B1/isoform 2-expressing cells. The Western blot was decorated with SLC35B1-specific antibody and visualized with peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies, Super Signal West Pico, and luminescence imaging. (d) HeLa cells were transfected with an expression plasmid encoding SLC35B1-GFP for 8 h, the nuclei were stained with DAPI, and the ER was visualized with Sec62-specific antibody plus Alexa-Fluor-594-coupled secondary antibody and subjected to fluorescence imaging using a super-resolution Elyra microscope. Representative images and merged images are shown (scale bar 10 µm).

2. SLC35B1 is AXER, the ATP/ADP Exchanger in the Membrane of the Endoplasmic Reticulum

2.1. SLC35B1 is an ER mMembrane pProtein in HeLa cCells

First, we confirmed the ER localization of human SLC35B1 by demonstrating the presence of SLC35B1/Isoform 2 (NM_005827.2) by immunoblot with a specific anti-SLC35B1 antibody in a highly enriched membrane protein extract from pancreatic rough microsomes, which are routinely used for the analysis of ER protein import[6][7] [6][7] and as a source of mammalian ER proteins such as BiP (Figure 2c)[26][27] [26][27]. Next, we expressed GFP-tagged SLC35B1 in HeLa cells at a moderate level and confirmed its ER localization (Figure 2d)[27] [27]. These results were consistent with the localization of human SLC35B1 according to The Human Protein Atlas and with the localization of SLC35B1 in C. elegans[23] [23], S. cerevisiae[22] [22], S. pombe[22] [22], and A. thaliana (AtUTr1)[24] [24].

2.2. Heterologously eExpressed SLC35B1 is an ATP/ADP aAntiporter

To test whether SLC35B1 might act as an ATP/ADP transporter, we expressed cDNAs for SLC35B1 (P78383.1, NM_005827.1) and SLC35B1/Isoform 2 (NM_005827.2) in Escherichia coli cells, routinely used to characterize nucleotide transport proteins[15][16][28] [15][16][28]. The two heterologously expressed SLC35B1 isoforms were highly specific for ATP and ADP, with no competition from AMP, CTP, GTP, UTP, UDP-glucose, or UDP-galactose (its putative substrate) with [a32P]ATP import[27] [27].

The fact that newly imported [a32P]ATP could be chased from the cells by addition of an excess of unlabeled ATP already suggested that both SLC35B1 isoforms act in an antiport mode[27] [27]. To further substantiate this transport mechanism, membrane proteins of the respective transfected cells were solubilized in detergent and reconstituted into liposomes. Both, SLC35B1 and SLC35B1/Isoform 2 were able to facilitate the import of ATP or ADP into proteoliposomes, loaded with ADP or ATP, whereas no import was detectable in absence of loading substrates[27] [27]. This fact verified that the two SLC35B1 isoforms catalyze the strict antiport of ATP and ADP.

2.3. SLC35B1 is sSimilar to the ER rResident ATP cCarrier

Heterologously expressed SLC35B1 exhibited similar apparent KM and Vmax values for ATP (32.6 - 34.7 µM and 871.0 – 904.5 pmol mg protein-1 h-1) and ADP (32.0 - 37.3 µM and 888.4 - 962.3 pmol mg protein-1 h-1), as SLC35B1/Isoform 2[27] [27]. These apparent affinities of SLC35B1 for ATP are in line with data on ATP and ADP import into proteoliposomes, harboring the full complement of mammalian ER membrane proteins[9][11][14] [9][11][14]. Notably, substrate specificity and antiport mode of the two SLC35B1 isoforms were also shared by the ATP/ADP carriers, which were present in proteoliposomes, harboring the full complement of mammalian ER membrane proteins[27] [27]. In addition, ATP import into these proteoliposomes was dependent on their preloading with ADP and not competed by AMP or other nucleoside triphosphates[27] [27]. Furthermore, the two heterologously expressed SLC35B1 isoforms and the ER membrane resident ATP transport activity shared an insensitivity towards EDTA, i.e. transport Mg2+-free ATP.

Based on the ATP and ADP transport characteristics of the heterologously expressed SLC35B1 isoforms 1 and 2 and their similarities to the ATP and ADP transport activities that are present in proteoliposomes with the full complement of mammalian ER membrane proteins, the two SLC35B1 isoforms 1 and 2 were found to be good candidates to work as ATP/ADP exchangers in the human ER membrane.

2.4. Depletion of SLC35B1 from HeLa cCells rReduces ER ATP lLevels and BiP aActivity

To directly address whether SLC35B1 acts as a transporter of chemical energy in the ER in human cells, HeLa cells were treated with two different SLC35B1-targeting siRNAs for 96 h, and the knockdown efficiencies were evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. The analysis showed that mRNA depletion was efficient, i.e. the 5´ untranslated region (UTR)-targeting siRNA knocked down the residual SLC35B1 level to ~10% and the coding region-targeting siRNA to ~20%[27] [27]. Depletion of SLC35B1 for 96 h did not cause any major alterations in whole cell or ER morphology[27].

Next, the energy status of SLC35B1-depleted cells was characterized with time-resolved live cell recordings of ER ATP levels using the ER-targeted and genetically-encoded ATP FRET sensor ERAT4.01[17] [17]. ATP levels were detected and compared in the ER of HeLa cells treated either with two different SLC35B1-targeting or control siRNAs, followed by ERAT4.01 transfection. SLC35B1 knockdown was correlated with significantly lower ATP levels in the ER compared to control cells[27] [27]. Thapsigargin (Tg), which inhibits sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) in the ER membrane and stimulates Ca2+ release from the ER, led to the expected increase in the ER ATP levels[27] [27]. The succeeding application of 2-deoxy-glucose (2-DG), which reduces the availability of ATP in the cytosol due to inhibition of glycolysis, induced the expected drop in ER ATP levels[27] [27]. In contrast, the response of SLC35B1 knockdown cells to both Tg and 2-DG was less pronounced[27] [27]. Thus, SLC35B1 knockdown in HeLa cells reduced ATP levels in the ER and these levels could not be replenished by Tg-induced Ca2+ efflux from the ER.

To further substantiate the observed siRNA effects, we performed complementation analysis, i.e. expression of SLC35B1 cDNA in HeLa cells after knock down of endogeneous SLC35B1 mRNA with the 5´ untranslated region (UTR)-targeting siRNA[27] [27]. In summary, the results from the heterologous expression experiments, SLC35B1 knockdown in HeLa cells in combination with live cell imaging of ATP levels in the ER, and complementation experiments indicated that SLC35B1 and SLC35B1/Isoform 2 represent ATP/ADP exchangers in the human ER membrane that are responsible for net import of chemical energy into the ER.

ER lumenal ATP allows BiP to fulfill its physiological roles, e.g. in facilitating selective protein import into the ER[6][7][29] [6][7][29] and in limiting Ca2+ leakage from the ER[6][26] [6][26], both by affecting gating of the Sec61 channel (Figure 1). In the next series of experiments, SLC35B1 depletion phenocopied the effect of BiP depletion on BiP-dependent ER protein import[27] [27]. In addition, ATP depletion in the ER driven by SLC35B1 knockdown decreased ER Ca2+, i.e. stimulated ER Ca2+ efflux, as it had previously been observed after BiP depletion[27] [27]. Thus, depletion of ATP from the ER results in reduced BiP activity, which causes reduced BiP-dependent ER protein import and increased ER Ca2+ efflux. Therefore, these results confirmed the conclusion that SLC35B1 represents the ATP/ADP exchanger in the human ER membrane.

2.5. SLC35B1 mMay be pPart of a Ca2+-dDependent r

Regulatory cCircuit

Finally, we tested if SLC35B1 is involved in controlling cellular energy homeostasis in response to ER ATP depletion. AMPK is the master regulator of energy metabolism (FigureFigure 1) 1)[17][19][30][31][17][19][30][31] and can be activated by a decrease in cytosolic ATP levels or by an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ via the calcium/calmodulin dependent kinase kinase 2 (CAMKK2)[31] [31].

First, we addressed cytosolic ATP levels as the potential AMPK regulator. Therefore, we monitored ATP levels in the cytosol in real-time using the cytosolic ATP sensor Ateam[27] [27] and in cellular lysates using a bioluminescent assay. SLC35B1 depletion from HeLa cells did not significantly affect cytosolic ATP levels or the total cellular ATP levels, which is consistent with the facts that HeLa cells are not professional secretory cells and that the ER in HeLa cells does not significantly contribute to the total cellular ATP levels[27] [27].

The results discussed in 2.4. already suggested that Tg-induced increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and the concomitant increase in ATP levels in the ER were an effect of Ca2+ on cytosolic ATP production. Therefore, we hypothesized that the observed drop in ATP levels in the ER lumen in response to SLC35B1 knockdown might activate a signaling mechanism that controls ER and cytosolic Ca2+ levels. This cascade would start with reduction in BiP activity and subsequent increase in Ca2+ leakage from the ER via open Sec61 channels. This hypothesis was tested positive in the above-described Ca2+ imaging experiments[27] [27].

At last, we asked how SLC35B1 knockdown may directly affect cytosolic ATP production. HeLa cells were treated with the two SLC35B1-targeting siRNAs for 96 h and the cell lysates were analysed by Western blotting using antibodies against the phosphorylated alpha and beta subunits of AMPK. We found that SLC35B1 knockdown resulted in pronounced AMPK phosphorylation, which is expected to stimulate cytosolic ATP production[27] [27].

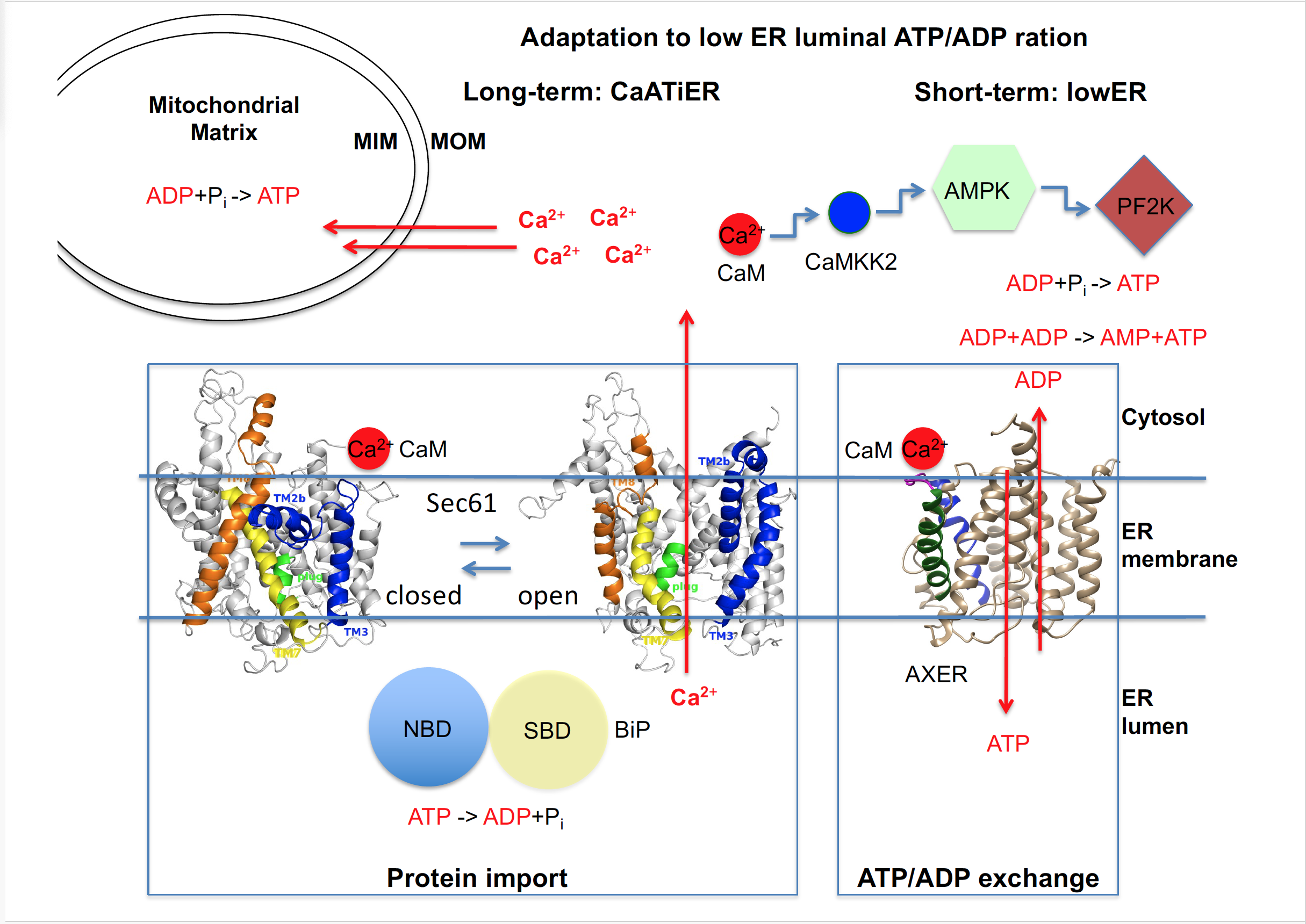

Thus, AXER appeared to be part of a regulatory circuit and a Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway, termed lowER, acting in vicinity of the ER and guaranteeing sufficient ATP supply to the ER (Figure 3)[27]Figure 3 [27]. The initial experimental data to characterize this putative signaling pathway suggested the following scenario for lowER: A high ATP/ADP ratio in the ER allows BiP to limit Ca2+ leakage from the ER via the Sec61 channel[6] [6]. A low ATP/ADP ratio due to increased protein import and folding or due to protein misfolding, leads to BiP dissociation from the Sec61 channel thus inducing Ca2+ leakage from the ER[6] [6]. In the cytosol, Ca2+ binds to calmodulin (CaM) near the ER surface[32] [32], and activates AMPK via CAMKK2 and finally PF2K[17] [17]. Activated PF2K causes increased ADP phosphorylation in glycolysis, leading to ATP import into the ER via AXER, which is also activated by Ca2+ efflux from the ER[17] [17]. Interestingly, mammalian AXER comprises an IQ motif in the cytosolic loop between transmembrane domains 2 and 3 (Figure 2) and, thus, may also be activated by Ca2+-CaM. Normalization of the ER ATP/ADP ratio, causes BiP to limit the Ca2+ leakage and thus inactivates the signal transduction pathway. SERCA, which pumps Ca2+ back into the ER lumen, balances the passive Ca2+ efflux and protein phosphatase 2 (PP2) dephosphorylates AMPK. Notably all mentioned proteins are present in sufficient quantities in the HeLa cells which were used here[33] [33] and it is expected that lowER involves sites of contact between ER and mitochondria and oxidative phosphorylation as an energy source in non-cancer cells[34][35][36][37] [34][35][36][37]. Furthermore, activated AMPK was shown previously to lead to reduced cap-dependent translation and therefore ties the lowER to the UPR[19][38] [19][38]. While ADP is exported via AXER, phosphate may leave the ER via the Sec61 channel, which is not ion selective[26] [26] and which may be even permeable to glutathione[39] [39].

Figure 3. | ER low energy response (lowER) contributes to a sufficient initial ATP supply to the human ER. AXER, ATP/ADP exchanger in the ER membrane = SLC35B1; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CaM, Calmodulin; CaMKK2, Ca2+ CaM-dependent kinase kinase 2; MIM, mitochondrial inner membrane; MOM, mitochondrial outer membrane; NBD, nucleotide binding domain of BiP; PF2K, 6-phospho-fructo-2-kinase; Pi, inorganic phosphate; SBD, substrate binding domain of BiP. Notably, ATP production in HeLa cells relies mainly on glycolysis (in the cytosol) rather than on oxidative phosphorylation (in mitochondria). See text for details.

3. Recent Work Settled the Dust on the Discovery and Initial Characterization of AXER and Warrants an Update on the Paradigm Shift in SLC35B1 Research

Our above-described data showed that AXER is not only the long-sought ATP importer and ADP exporter in the ER membrane, but may also be part of an ER to cytosol low energy response regulatory axis (termed lowER) (Figure 3). Our findings explained why AXER orthologs in Saccharomyes cerevisiae (HUT1), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (HUT1), and Caenorhabditis elegans (HUT-1) have been found to play a more general role in ER homeostasis, as would be expected for a nucleotide sugar transporter. However, it remained open if AXER is the only ATP carrier in the ER membrane of mammalian cells (see below). Notably, its ortholog in C. elegans is essential only during larval development but not in the adult worm[23] [23]. The proposed Ca2+ dependent regulatory circuit lowER guarantees ER energy metabolism on the short term and thus ER proteostasis under physiological conditions and still awaits further validation and characterization[40][41] [40][41]. Under patho-physiological conditions, it can be expected to represent the first line of defense of a cell against ER stress and, therefore, may interact with the unfolded protein response[38] [38].

3.1. Cell bBiological eExperiments after AXER iIdentification

Subsequent experiments with HeLa, INS-1, and CHO cells provided evidence that SLC35B1 transports ATP into the ER as energy source for the folding process mediated by ER luminal chaperones[37] [37]. In addition, this work provided novel insights into questions about maintenance and re-supply of ER energy homeostasis. AXER was proposed to be part of another regulatory mechanism, termed Ca2+-antagonized transport into the ER or CaATiER, which was proposed to guarantee sufficient ATP supply to the ER on the long term (Figure 3). The initial experimental data to characterize this putative signaling pathway demonstrated that mitochondria supply ATP to the ER and a SERCA-dependent Ca2+ gradient across the ER membrane is necessary for ATP transport into the ER via AXER. The following scenario was suggested: “Under physiological conditions, increases in cytosolic Ca2+ inhibit ATP import into the ER lumen to limit ER ATP consumption”. Furthermore, “ER protein mis-folding increases ATP uptake from mitochondria into the ER”[37]. Initially, even in the experiments which gave rise to the CaATiER model, the previously observed almost instantaneously increase in ER ATP levels was observed as a short-term and short-distance (i.e. the immediate ER neighborhood) response to SERCA inhibition over a period of five minutes, i.e. Ca2+ efflux from the ER into the cytosol.

These findings raise the possibility that there may actually be two phases associated with Ca2+-coupled ER ATP homeostasis (Figure 3). A first phase that corresponds to lowER and a second one that was termed CaATiER. Such a biphasic adaptation scenario would be consistent with the observations that in HeLa cells the ATP for ER uptake is initially supplied mainly by anaerobic glycolysis and subsequently by oxidative phosphorylation and that there are cell-type specific variations, possibly reflecting the different ratios between substrate level- and oxidative-phosphorylation of ADP in different cell-types and under different metabolic conditions. The question is what the benefit of having these two phases may be. In the experiments, which gave rise to the CaATiER model, the authors also studied the effect of protein mis-folding in the ER and observed that it stimulates Ca2+ transfer from the ER to mitochondria and that ER ATP homeostasis becomes more dependent on oxidative phosphorylation. Therefore, we proposed that lowER may describe the ad hoc regulation of ER homeostasis under physiological conditions, i.e. whenever the ATP to ADP ratio drops in the ER, to prevent problems of protein mis-folding and that CaATiER may best describe patho-physiological conditions such as protein mis-folding, where the demand for ATP becomes particularly high. Thus, the two regulatory mechanisms of AXER are probably two successional phases of the same signaling response[41] [41].

3.2. Biochemical eExperiments after AXER iIdentification

More recently, classical biochemical approaches were employed to characterize the human AXER after its expression in yeast[42] [42]. The purified and reconstituted exchanger was extensively characterized with respect to affinities as well as transport rates and found to have a more than ten times higher affinity for ATP on the assumed cytosolic face of the proteoliposomal membrane than on the luminal side. In this experimental setting, SLC35B1 exhibited apparent KM and Vmax values for ATP of 72.5 7.0 µM and 13.5 pmol mg protein-1 min-1. Furthermore, AXER accepted the di- and tri-nucleotides -most notably UDP and UTP- as substrates but not mono-nucleotides and nucleotide sugars. It was concluded that AXER promotes ATP import into the ER in exchange for ADP as well as UDP, which both represent the side products in folding and N-glycosylation of newly-synthesized proteins in the ER lumen.

3.3. Novel mMechanistic iInsights bBased on sStructural bBiology

Most recent work further validated the physiological functions, structure and transport mechanism of human AXER[43]. The purified exchanger was characterized after its expression in yeast by a whole plethora of biochemical/biophysical techniques and by cryo-EM. Thermal shift assays and STD-NMR demonstrated that AXER binds ATP and ADP with high affinity but AMP and UDP-galactose with negligible affinity. Reconstituted AXER confirmed this substrate preferences and showed a turnover rate of 12 ATP min-1, which is much higher than the kcat of BiP (0.013 ATP min-1) and has to be seen in the context of the concentrations of the two proteins in HeLa cells (BiP, 8.253 µM; SLC35B1, 17.6 nM)[33] [33]. The seven cryo-EM structures confirmed the expected DMT-fold but, in contrast to other DMTs, did not indicate an ability to form a homodimer. Thus, the exchanger comprises two structurally similar four-transmembrane helix bundles that are made up from two overlooking V-shaped transmembrane helical pairs. The structures also elucidated an asymmetry between the cytosol- and lumen-facing substrate binding sites and, therefore, suggested a stepwise ATP translocation mechanism, which includes vertical repositioning of the substrate and represents a novel model for substrate translocation by an SLC transporter. Furthermore, AXER was observed to be one of the five most essential SLCs in a CRISPR-Cas9 screen with human colon cancer HCT116 cells.

References

- Haas, I.; Wabl, M. Immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein. Nature 1983, 306, 387-389.

- Hendershot, L.M.; Ting, J.; Lee, A.S. Identity of the immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein with the 78,000-dalton glucose-regulated protein and the role of posttranslational modifications in its binding function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988, 8, 4250-4256.

- 3. Lievremont, J.P.; Rizzuto, R.; Hendershot, L.; Meldolesi, J. BiP, a major chaperone protein of the endoplasmic reticulum lumen, plays a direct and important role in the storage of the rapidly exchanging pool of Ca2+. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 30873-30879.

- Hamman, B.D.; Hendershot, L.M.; Johnson, A.E. BiP maintains the permeability barrier of the ER membrane by sealing the luminal end of the translocon pore before and early in translocation. Cell 1998, 92, 747-758.

- Bertolotti, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hendershot, L.M.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000 2, 326-332.

- Schäuble, N.; Lang, S., Jung, M., Cappel, S., Schorr, S., Ulucan, Ö., Linxweiler, J., Dudek, J., Blum, R., Helms, V., Paton, A. W., Paton, J. C., Cavalié, A.; Zimmermann, R. BiP-mediated closing of the Sec61 channel limits Ca2+ leakage from the ER. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3282-3296.

- Tyedmers, J.; Lerner, M.; Wiedmann, M.; Volkmer, J.; Zimmermann, R. Polypeptide chain binding proteins mediate completion of cotranslational protein translocation into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum.EMBO rep. 2003,4, 505-510.

- Clairmont, C.A.; De Maio, A.; Hirschberg, C.B. Translocation of ATP into the lumen of rough endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles and its binding to luminal proteins including BiP (GRP 78) and GRP 94. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 3983-3990.

- Mayinger, P.; Meyer, D.I. An ATP transporter is required for protein translocation into the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 659-666.

- Guillen, E.; Hirschberg, C.B. Transport of adenosine triphosphate into endoplasmic reticulum proteoliposomes. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 5472-5476.

- Kim, S.-h.; Shin, S.-j.; Park, J.-S. Identification of the ATP transporter of rat liver rough endoplasmic reticulum via photoaffinity labeling and partial purification. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 5418-5425.

- Mayinger, P., Bankaitis, V.A., and Meyer, D.I. Sac1p mediates the adenosine triphosphate transport into yeast endoplasmic reticulum that is required for protein translocation. J. Cell Biol. 1995 131, 1377-1386.

- Kochendörfer, K.-U.; Then, A.R.; Kearns, B.G.; Bankaitis, V.A.; Mayinger, P. Sac1p plays a crucial role in microsomal ATP transport, which is distinct from its function in Golgi phospholipid metabolism. EMBO J. 1999 18, 1506-1515.

- Shin, S.J.; Lee, W.K.; Lim, H.W.; Park, J.-S. Characterization of the ATP transporter in the reconstituted rough endoplasmic reticulum proteoliposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembranes 2000, 1468, 55-62.

- Leroch, M.; Neuhaus, E.H.; Kirchberger, S.; Zimmermann, S.; Melzer, M.; Gerhold, J.; Tjaden, J. Identification of a novel adenine nucleotide transporter in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 438–451.

- Chu, L.; Gruber, A.; Ast, M.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Altensell, J.; Neuhaus, E.H.; Kroth. P.G.; Haferkamp, I. Shuttling of (deoxy-) nucleotides between compartments of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. New Phytol. 2017. 213, 193-205.

- Vishnu, N.,N.; Jadoon Khan, M.; Karsten, F.; Groschner, L.N.; Waldeck-Weiermair, M.; Rost, R.; Hallström, S.; Imamura, H.; Graier, W.F.; Malli, R. ATP increases within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum upon intracellular Ca2+ release. Mol Biol Cell 25, 368-379. ATP increases within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum upon intracellular Ca2+ release. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 368-379.

- Boß, M.; Newbatt, Y.; Gupta, S.; Collins, I.; Brüne, B.; Namgaladze, D. AMPK-independent inhibition of human macrophage ER stress response by AICAR. Sci. rep. 2016,6, 32111.

- Preston, A.M.; Hendershot, L.M. Examination of a second node of translational control in the unfolded protein response. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 4253-4261.

- Jack, D.L.; Yang, N.M.; Saier Jr, M.H. The drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Eur. J. Biochem.2001, 268, 3620-3639.

- Schlessinger, A., Yee, S. W., Sali, A. & Giacomoni, K. M. SLC classification: an update. Clin. Pharma. Therap. 2013, 94, 19-22.

- Nakanishi, H.; Nakayama, K.; Yokota, A.; Tachikawa, H.; Takahashi, N.; Jigami, Y. Hut I proteins indentified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe are functional homologues involved in the protein-folding process at the endoplasmic reticulum. Yeast 2001, 18, 543-554.

- Dejima, K.; Murata, D.; Mizuguchi, S.; Nomura, K.H.; Gengyo-Ando, K.; Mitani, S.; Kamiyama, S.; Nishihara, S.; Nomura, K. The ortholog of human solute carrier family 35 member B1 (UDP-galactose transporter-related protein1) is involved in maintenance of ER homeostasis and essential for larval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 2215-2225.

- Reyes, F.; Merchant, L.; Norambuena, L.; Nilo, R.; Silva, H.; Orella, A. AtUTr1, a UDP-glucose/UDP-galactose transporter from Arabidopsis thaliana, is located in the endoplasmic reticulum and up-regulated by the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9145-9151.

- Tsuchiya, H.; Doki, S.; Takamoto, M.; Ikuta, T.; Higuchi, T.; Fukui, K.; Usuda, Y.; Tabuchi, E.; Nagatoishi, S.; Tsumoto, K.; Nishizawa, T.; Ito, K.; Dohmae, N.; Ishitani, R.; Nureki, O. Structural basis for amino acid export by DMT superfamily transporter YddG. Nature 2016,534, 417-420.

- Wirth, A.; Jung, M., Bies, C., Frien, M., Tyedmers, J., Zimmermann, R.; Wagner, R. The Sec61p complex is a dynamic precursor activated channel. Mol. Cell. 2003, 12, 261-268.

- Klein, M.-C.; Zimmermann, K.; Schorr, S.; Landini, M.; Klemens, P.A.W.; Altensell, J.; Jung, M.; Krause, E.; Nguyen, D.; Helms, V.; Rettig, J.; Fecher-Trost, C.; Cavalié, A.; Hoth, M.; Bogeski, I.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S.; Haferkamp, I. AXER is an ATP/ADP exchanger in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 3489.

- Haferkamp, I.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Linka, N.; Urbany, C.; Collingro, A.; Wagner, R.; Horn, M.; Neuhaus, H.E. A candidate NAD+ transporter in an intracellular bacterial symbiont related to Chlamydiae. Nature 2004, 432, 622-625.

- Haßdenteufel, S.; Johnson, N.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; High, S.; Zimmermann, R. Chaperone-mediated Sec61 channel gating during ER import of small presecretory proteins overcomes Sec61 inhibitor-reinforced energy barrier. Cell rep. 2018,23, 1373-1386.

- Long, Y.C.; Zierath, J.R. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in metabolic regulation. J. Clin. Invest. 2006,116, 1776-1783.

- Jeon, S.-M. Regulation and function of AMPK in physiology and diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e245.

- Erdmann, F.; Schäuble, N.; Lang, S.; Jung, M.; Honigmann, A.; Ahmad, M.; Dudek, J.; Benedix, J.; Harsman, A.; Kopp, A.; Helms, V.; Cavalié, A.; Wagner, R.; Zimmermann, R. Interaction of calmodulin with Sec61a limits Ca2+ leakage from the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 17-31.

- Hein, M.Y.; Hubner, N.C., Poser, I., Cox, J., Nagaraj, N., Toyoda, Y., Gak, I.A., Weisswange, I., Mansfeld, J., Buchholz, F., Hyman, A.A., Mann, M. A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometrics and abundances. Cell 2015, 163, 712-723.

- Bravo, R.; Vicencio, J.M.; Parra, V.; Troncoso, R.; Munoz, J.P.; Bui, M.; Quiroga, C.; Rodriguez, A.E.; Verdejo, H.E.; Ferreira, J.; Iglewski, M.; Chiong, M.; Simmen, T.; Zorzano, A.; Hill, J.A.; Rothermel, B.A.; Szabadkai, G.; Lavandero, S. Increased ER–mitochondrial coupling promotes mitochondrial respiration and bioenergetics during early phases of ER stress. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 2143-2152

- Hayashi, T.; Rizzuto, R.; Hajnoczky, G.; Su, T.-P. MAM: more than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol. 2009, 19, 81-88.

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.-P. Sigma-1 Receptor Chaperones at the ER- Mitochondrion Interface Regulate Ca2+ Signaling and Cell Survival. Cell 2007, 131, 596-610.

- Yong, J.; Bischof, H.; Burgstaller, S.; Siirin, M.; Murphy, A.; Malli, R.; Kaufman, R.J. Mitochondria supply ATP to the ER through a mechanism antagonized by cytosolic Ca2+. eLife 2019, 8, e49682

- Malli, R.; Graier, W.F. IREa modulates ER and mitochondria crosstalk. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 667-668.

- Ponsero, A.J.; Igbaria A, Darch MA, Miled S, Outten CE, Winther JR, Palais G, D'Autreaux B, Delaunay-Moisan A, Toledano MB. Endoplasmic reticulum transport of glutathione by Sec61 is regulated by Ero1 and BiP. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 962-973.

- Depaoli, M.R.; Hay, J.C.; Graier, W.F.; Malli, R. The enigmatic ATP supply of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 610-628.

- Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S. A little AXER ABC: ATP, BiP, and calcium form a triumvirate orchestrating energy homeostasis of the ER. Contact 2020, DOI: 10.1177/2515256420926795.

- Schwarzbaum, P.J.; Schachter, J.; Bredeston, L.M; The broad range di- and tri-nuleotide exchanger SLC35B1 displays asymmetrical affinities for ATP transport across the ER membrane. J. Biol. Chem.2022, 298, 101537.

- Gulai, A.; Ahn, Do-H.; Suades, A.; Hult, Y.; Wolf, G.; Iwata, S.; Superti-Furga, G.; Nomura, N.; Drew, D. Stepwise ATP translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum by human SLC35B1. Nature 2025 643, 855-864.

References

- Haas, I.; Wabl, M. Immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein. Nature 1983, 306, 387-389.

- Hendershot, L.M.; Ting, J.; Lee, A.S. Identity of the immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein with the 78,000-dalton glucose-regulated protein and the role of posttranslational modifications in its binding function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988, 8, 4250-4256.

- Lievremont, J.P.; Rizzuto, R.; Hendershot, L.; Meldolesi, J. BiP, a major chaperone protein of the endoplasmic reticulum lumen, plays a direct and important role in the storage of the rapidly exchanging pool of Ca2+. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 30873-30879.

- Hamman, B.D.; Hendershot, L.M.; Johnson, A.E. BiP maintains the permeability barrier of the ER membrane by sealing the luminal end of the translocon pore before and early in translocation. Cell 1998, 92, 747-758.

- Bertolotti, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hendershot, L.M.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000 2, 326-332.

- Schäuble, N.; Lang, S., Jung, M., Cappel, S., Schorr, S., Ulucan, Ö., Linxweiler, J., Dudek, J., Blum, R., Helms, V., Paton, A. W., Paton, J. C., Cavalié, A.; Zimmermann, R. BiP-mediated closing of the Sec61 channel limits Ca2+ leakage from the ER. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3282-3296.

- Tyedmers, J.; Lerner, M.; Wiedmann, M.; Volkmer, J.; Zimmermann, R. Polypeptide chain binding proteins mediate completion of cotranslational protein translocation into the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum.EMBO rep. 2003,4, 505-510.

- Clairmont, C.A.; De Maio, A.; Hirschberg, C.B. Translocation of ATP into the lumen of rough endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles and its binding to luminal proteins including BiP (GRP 78) and GRP 94. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 3983-3990.

- Mayinger, P.; Meyer, D.I. An ATP transporter is required for protein translocation into the yeast endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 659-666.

- Guillen, E.; Hirschberg, C.B. Transport of adenosine triphosphate into endoplasmic reticulum proteoliposomes. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 5472-5476.

- Kim, S.-h.; Shin, S.-j.; Park, J.-S. Identification of the ATP transporter of rat liver rough endoplasmic reticulum via photoaffinity labeling and partial purification. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 5418-5425.

- Mayinger, P., Bankaitis, V.A., and Meyer, D.I. Sac1p mediates the adenosine triphosphate transport into yeast endoplasmic reticulum that is required for protein translocation. J. Cell Biol. 1995 131, 1377-1386.

- Kochendörfer, K.-U.; Then, A.R.; Kearns, B.G.; Bankaitis, V.A.; Mayinger, P. Sac1p plays a crucial role in microsomal ATP transport, which is distinct from its function in Golgi phospholipid metabolism. EMBO J. 1999 18, 1506-1515.

- Shin, S.J.; Lee, W.K.; Lim, H.W.; Park, J.-S. Characterization of the ATP transporter in the reconstituted rough endoplasmic reticulum proteoliposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembranes 2000, 1468, 55-62.

- Leroch, M.; Neuhaus, E.H.; Kirchberger, S.; Zimmermann, S.; Melzer, M.; Gerhold, J.; Tjaden, J. Identification of a novel adenine nucleotide transporter in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 438–451.

- Chu, L.; Gruber, A.; Ast, M.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Altensell, J.; Neuhaus, E.H.; Kroth. P.G.; Haferkamp, I. Shuttling of (deoxy-) nucleotides between compartments of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. New Phytol. 2017. 213, 193-205.

- Vishnu, N.,N.; Jadoon Khan, M.; Karsten, F.; Groschner, L.N.; Waldeck-Weiermair, M.; Rost, R.; Hallström, S.; Imamura, H.; Graier, W.F.; Malli, R. ATP increases within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum upon intracellular Ca2+ release. Mol Biol Cell 25, 368-379. ATP increases within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum upon intracellular Ca2+ release. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 368-379.

- Boß, M.; Newbatt, Y.; Gupta, S.; Collins, I.; Brüne, B.; Namgaladze, D. AMPK-independent inhibition of human macrophage ER stress response by AICAR. Sci. rep. 2016,6, 32111.

- Preston, A.M.; Hendershot, L.M. Examination of a second node of translational control in the unfolded protein response. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 4253-4261.

- Jack, D.L.; Yang, N.M.; Saier Jr, M.H. The drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Eur. J. Biochem.2001, 268, 3620-3639.

- Schlessinger, A., Yee, S. W., Sali, A. & Giacomoni, K. M. SLC classification: an update. Clin. Pharma. Therap. 2013, 94, 19-22.

- Nakanishi, H.; Nakayama, K.; Yokota, A.; Tachikawa, H.; Takahashi, N.; Jigami, Y. Hut I proteins indentified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe are functional homologues involved in the protein-folding process at the endoplasmic reticulum. Yeast 2001, 18, 543-554.

- Dejima, K.; Murata, D.; Mizuguchi, S.; Nomura, K.H.; Gengyo-Ando, K.; Mitani, S.; Kamiyama, S.; Nishihara, S.; Nomura, K. The ortholog of human solute carrier family 35 member B1 (UDP-galactose transporter-related protein1) is involved in maintenance of ER homeostasis and essential for larval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 2215-2225.

- Reyes, F.; Merchant, L.; Norambuena, L.; Nilo, R.; Silva, H.; Orella, A. AtUTr1, a UDP-glucose/UDP-galactose transporter from Arabidopsis thaliana, is located in the endoplasmic reticulum and up-regulated by the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9145-9151.

- Tsuchiya, H.; Doki, S.; Takamoto, M.; Ikuta, T.; Higuchi, T.; Fukui, K.; Usuda, Y.; Tabuchi, E.; Nagatoishi, S.; Tsumoto, K.; Nishizawa, T.; Ito, K.; Dohmae, N.; Ishitani, R.; Nureki, O. Structural basis for amino acid export by DMT superfamily transporter YddG. Nature 2016,534, 417-420.

- Wirth, A.; Jung, M., Bies, C., Frien, M., Tyedmers, J., Zimmermann, R.; Wagner, R. The Sec61p complex is a dynamic precursor activated channel. Mol. Cell. 2003, 12, 261-268.

- Klein, M.-C.; Zimmermann, K.; Schorr, S.; Landini, M.; Klemens, P.A.W.; Altensell, J.; Jung, M.; Krause, E.; Nguyen, D.; Helms, V.; Rettig, J.; Fecher-Trost, C.; Cavalié, A.; Hoth, M.; Bogeski, I.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S.; Haferkamp, I. AXER is an ATP/ADP exchanger in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 3489.

- Haferkamp, I.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Linka, N.; Urbany, C.; Collingro, A.; Wagner, R.; Horn, M.; Neuhaus, H.E. A candidate NAD+ transporter in an intracellular bacterial symbiont related to Chlamydiae. Nature 2004, 432, 622-625.

- Haßdenteufel, S.; Johnson, N.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; High, S.; Zimmermann, R. Chaperone-mediated Sec61 channel gating during ER import of small presecretory proteins overcomes Sec61 inhibitor-reinforced energy barrier. Cell rep. 2018,23, 1373-1386.

- Long, Y.C.; Zierath, J.R. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in metabolic regulation. J. Clin. Invest. 2006,116, 1776-1783.

- Jeon, S.-M. Regulation and function of AMPK in physiology and diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e245.

- Erdmann, F.; Schäuble, N.; Lang, S.; Jung, M.; Honigmann, A.; Ahmad, M.; Dudek, J.; Benedix, J.; Harsman, A.; Kopp, A.; Helms, V.; Cavalié, A.; Wagner, R.; Zimmermann, R. Interaction of calmodulin with Sec61a limits Ca2+ leakage from the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 17-31.

- Hein, M.Y.; Hubner, N.C., Poser, I., Cox, J., Nagaraj, N., Toyoda, Y., Gak, I.A., Weisswange, I., Mansfeld, J., Buchholz, F., Hyman, A.A., Mann, M. A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometrics and abundances. Cell 2015, 163, 712-723.

- Bravo, R.; Vicencio, J.M.; Parra, V.; Troncoso, R.; Munoz, J.P.; Bui, M.; Quiroga, C.; Rodriguez, A.E.; Verdejo, H.E.; Ferreira, J.; Iglewski, M.; Chiong, M.; Simmen, T.; Zorzano, A.; Hill, J.A.; Rothermel, B.A.; Szabadkai, G.; Lavandero, S. Increased ER–mitochondrial coupling promotes mitochondrial respiration and bioenergetics during early phases of ER stress. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 2143-2152.

- Hayashi, T.; Rizzuto, R.; Hajnoczky, G.; Su, T.-P. MAM: more than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol. 2009, 19, 81-88.

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.-P. Sigma-1 Receptor Chaperones at the ER- Mitochondrion Interface Regulate Ca2+ Signaling and Cell Survival. Cell 2007, 131, 596-610.

- Yong, J.; Bischof, H.; Burgstaller, S.; Siirin, M.; Murphy, A.; Malli, R.; Kaufman, R.J. Mitochondria supply ATP to the ER through a mechanism antagonized by cytosolic Ca2+. eLife 2019, 8, e49682.

- Malli, R.; Graier, W.F. IREa modulates ER and mitochondria crosstalk. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 667-668.

- Ponsero, A.J.; Igbaria A, Darch MA, Miled S, Outten CE, Winther JR, Palais G, D'Autreaux B, Delaunay-Moisan A, Toledano MB. Endoplasmic reticulum transport of glutathione by Sec61 is regulated by Ero1 and BiP. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 962-973.

- Depaoli, M.R.; Hay, J.C.; Graier, W.F.; Malli, R. The enigmatic ATP supply of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 610-628.

- Zimmermann, R.; Lang, S. A little AXER ABC: ATP, BiP, and calcium form a triumvirate orchestrating energy homeostasis of the ER. Contact 2020, DOI: 10.1177/2515256420926795.

- Schwarzbaum, P.J.; Schachter, J.; Bredeston, L.M; The broad range di- and tri-nuleotide exchanger SLC35B1 displays asymmetrical affinities for ATP transport across the ER membrane. J. Biol. Chem.2022, 298, 101537.