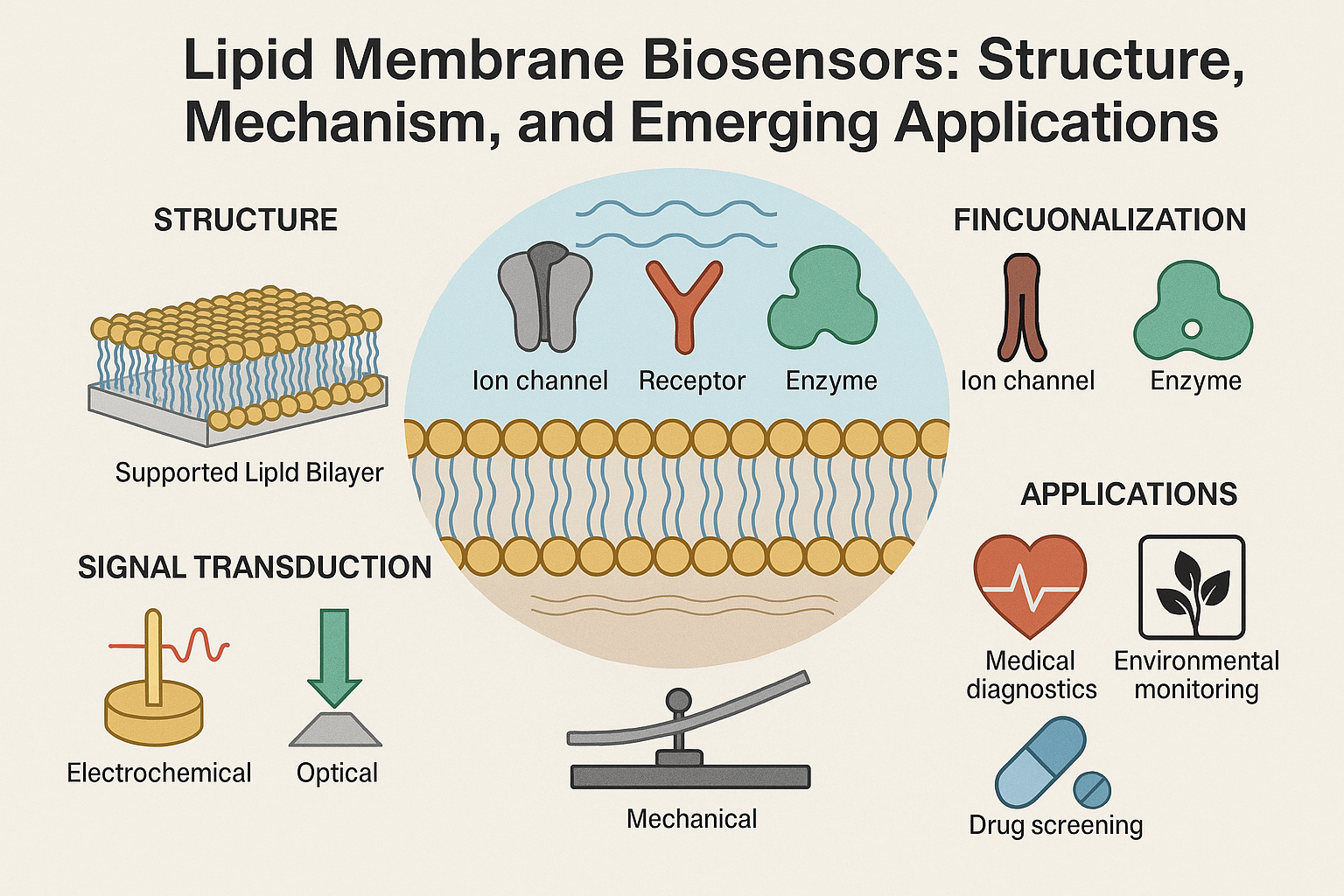

Lipid membrane-based biosensors have emerged as a powerful class of analytical devices, merging biological recognition with lipid bilayers to detect a wide range of analytes. These systems exploit the biomimetic properties of lipid membranes, offering high specificity, biocompatibility, and the ability to incorporate functional biomolecules such as receptors, enzymes, or ion channels. This review outlines the key design principles, fabrication techniques, detection mechanisms, and applications of lipid membrane-based biosensors, with a focus on their role in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and drug screening.

- Biosensors

- Lipid-Membrane

1. Introduction

Biosensors are devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a transducer to convert a biological event into a measurable signal. Among various biosensing platforms, lipid membrane-based biosensors have garnered significant attention due to their ability to closely replicate the physicochemical properties of cellular membranes [1][2](Sackmann, 1996; Tien & Ottova-Leitmannova, 2003). This structural mimicry allows for the functional integration of membrane-bound proteins and receptors, which are otherwise unstable in non-lipid environments [3](Jin & Bai, 2020).

Lipid-based biosensors provide a soft, flexible, and dynamic interface ideal for detecting biological molecules, making them highly suitable for applications in medical diagnostics, environmental analysis, and drug discovery. Their compatibility with a range of detection methods further enhances their versatility.

2. Structure and Fabrication of Lipid Membrane-Based Biosensors

2.1. Types of Lipid Membranes

Several structural formats have been developed for lipid membrane biosensors:

-

Black Lipid Membranes (BLMs): Freestanding bilayers formed over a small aperture in a hydrophobic support. BLMs have been foundational in the study of ion channels and electrophysiological processes due to their ability to mimic the fluid, dynamic properties of natural cell membranes. They are typically formed by painting a lipid solution across an aperture in a Teflon or similar hydrophobic partition. This results in a bilayer with an optically black appearance under reflected light, hence the name. BLMs allow for high sensitivity in current and voltage measurements, making them ideal for electrophysiological recordings. However, they are also highly fragile, prone to mechanical rupture, and have limited lifespan, which restricts their practical application in long-term sensing or field-deployable devices [4].(Tien & Ghosh, 2005).

-

Supported Lipid Bilayers (SLBs): These bilayers are formed on solid substrates such as glass, mica, or silicon oxide through methods like vesicle fusion, Langmuir-Blodgett deposition, or spin coating. SLBs offer significantly improved mechanical stability compared to BLMs and are compatible with high-resolution optical and surface-sensitive analytical techniques. Their close contact with the underlying substrate allows for excellent spatial resolution in sensing, particularly when combined with techniques such as fluorescence microscopy or atomic force microscopy. However, this proximity can also limit the mobility of large transmembrane proteins and affect the natural behavior of embedded biomolecules. To address this, polymer cushions or hydration layers are often introduced between the bilayer and the substrate to restore membrane fluidity and allow for better functional incorporation of proteins [1].(Sackmann, 1996).

-

Polymer-Cushioned Membranes: These use a soft polymer layer between the lipid bilayer and the supporting substrate, creating a hydrated space that prevents direct contact between the membrane and the solid surface. This configuration helps preserve the lateral mobility and conformational flexibility of embedded proteins, making it especially useful for incorporating integral membrane proteins and studying their dynamics. Commonly used polymers include polyethylene glycol (PEG), dextran, and agarose, which can be tailored in thickness and density to optimize membrane performance. Polymer-cushioned membranes improve the functional lifetime of biosensors and reduce nonspecific interactions with the surface, thereby enhancing both sensitivity and selectivity. They also offer improved resilience under flow conditions, making them more suitable for integration into microfluidic biosensor platforms. However, achieving uniform polymer layers and stable bilayer formation on top of these cushions can be technically demanding and may require advanced surface chemistry and precise control over deposition parameters.

-

Tethered Bilayer Lipid Membranes (tBLMs): These are synthetic bilayers anchored to a solid substrate via covalent or non-covalent spacer molecules, typically through thiol-linkers on gold surfaces or silane chemistry on glass. The spacer molecules create a nanometer-scale aqueous reservoir beneath the bilayer, allowing sufficient space for the incorporation of large transmembrane proteins while maintaining a stable configuration. This architecture combines the robustness of supported systems with improved biofunctionality. tBLMs are particularly advantageous in electrochemical biosensing due to their ability to form well-defined, reproducible electrical interfaces. They also exhibit enhanced mechanical stability and resistance to shear forces, which makes them suitable for real-time and flow-based applications. Advanced fabrication techniques, such as self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) and click-chemistry, have further improved the uniformity and reliability of tBLM formation. Despite their many advantages, the design and optimization of spacer systems can be complex, and improper tether density or length may restrict protein mobility or hinder signal transduction [5].(Cornell et al., 1997).

2.2. Functionalization

To achieve analyte specificity, lipid membranes are functionalized with:

-

Ion Channels: These transmembrane proteins form pores within lipid bilayers and are essential for the selective transport of ions across the membrane. In biosensors, both natural ion channels (e.g., gramicidin, alamethicin, α-hemolysin) and synthetic analogues are used to transduce biological interactions into electrical signals. Ion channels can function as highly sensitive and specific detectors for changes in ion concentrations, pH, membrane potential, and the presence of specific ligands. Channel activity can be modulated by the binding of target analytes, causing detectable changes in current or voltage. This makes them ideal for electrophysiological biosensors targeting neurotransmitters, toxins, or pharmaceuticals. Reconstitution of ion channels into artificial membranes requires careful control of orientation and insertion, but once incorporated, they offer exceptional single-molecule sensitivity and real-time response. Some designs use ligand-gated ion channels or voltage-gated channels to add specificity and tunability to the sensing platform.

-

Receptors: These are integral membrane proteins or membrane-associated biomolecules that specifically recognize and bind target ligands, including hormones, neurotransmitters, antigens, or drug compounds. In biosensor platforms, receptors such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), ionotropic receptors, and tyrosine kinase receptors are often embedded in lipid membranes to maintain their native conformation and activity. The binding of a target molecule to the receptor can initiate conformational changes or signal cascades that are transduced into measurable outputs, such as changes in ion flux, impedance, or fluorescence. Functionalizing membranes with receptors allows for highly selective biosensing, especially in medical diagnostics and pharmacological testing. Immobilization strategies must ensure that the receptor’s binding site is accessible and functional. Newer approaches utilize recombinant receptors or receptor fragments engineered for stability and selectivity. Lipid membrane platforms provide a native-like lipid environment critical for maintaining receptor activity, particularly for sensitive targets like GPCRs.

-

Enzymes: These catalytic biomolecules are widely used in biosensor platforms for their ability to convert specific substrates into detectable products. In lipid membrane-based biosensors, enzymes can be anchored directly to the lipid surface or incorporated into the bilayer using hydrophobic anchors or affinity tags. Their role is often to catalyze a biochemical reaction that generates a measurable signal, such as the production of protons, electrons, or chromogenic compounds. Common examples include glucose oxidase for glucose detection, acetylcholinesterase for nerve agent sensing, and urease for urea monitoring. The lipid environment can stabilize enzyme structure and maintain activity, especially when the enzyme has a membrane-associated or lipophilic domain. Moreover, the combination of enzymatic selectivity with membrane-based signal amplification allows for enhanced sensitivity and real-time response. Challenges include ensuring sufficient enzyme loading and activity, minimizing nonspecific adsorption, and maintaining long-term stability under physiological conditions.

-

Synthetic Recognition Elements: These include artificially engineered molecules such as aptamers, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), peptidomimetics, and synthetic receptors that mimic the binding behavior of natural biomolecules. Aptamers are short single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that can fold into unique three-dimensional structures capable of high-affinity binding to target molecules ranging from ions and small organics to proteins and cells. MIPs are polymer networks formed around a template molecule, which is later removed to leave behind a selective binding site. These elements offer high chemical and thermal stability, reusability, and the ability to design for targets that lack suitable natural ligands. When integrated into lipid membranes, synthetic recognition elements can enhance sensor robustness and reduce reliance on fragile biological components. They are especially valuable for detecting toxins, pollutants, and pharmaceutical agents in harsh or variable environments. One major challenge is ensuring compatibility with the lipid matrix, as improper integration may affect membrane integrity or recognition efficiency. However, with advancements in supramolecular chemistry and nanoscale patterning, these synthetic components are increasingly tailored for seamless functionalization in biosensor platforms [6].(Anderson & Han, 2021).

Fabrication techniques include Langmuir-Blodgett deposition, vesicle fusion, solvent-assisted bilayer formation, and microfluidic-assisted self-assembly (Jin & [3]Bai, 2020).

3. Signal Transduction Mechanisms

Lipid membrane biosensors employ various detection strategies to convert biological interactions into quantifiable signals:

Electrochemical Transduction: This is one of the most widely used signal transduction strategies in lipid membrane biosensors due to its high sensitivity, portability, and low cost. Electrochemical biosensors convert biochemical interactions into electrical signals, typically measured as current (amperometric), voltage (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric) changes. When lipid membranes are integrated with electrodes, they act as a sensitive interface for detecting ion fluxes or redox reactions triggered by analyte binding. Amperometric sensors measure the current resulting from the oxidation or reduction of electroactive species generated during the analyte interaction. Potentiometric sensors detect changes in membrane potential resulting from ion exchange, often using ion-selective electrodes. Impedimetric biosensors monitor variations in electrical impedance due to changes in membrane capacitance or resistance as molecules bind or diffuse through the membrane.

Tethered or supported bilayers provide a stable platform for immobilizing recognition elements and enhancing electrical coupling with the transducer. Innovations in nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes—such as carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles, and conductive polymers—further amplify signal output and improve detection limits. Redox-active mediators can also be embedded within or adjacent to the membrane to shuttle electrons more efficiently to the electrode surface, enhancing sensitivity and reducing the need for direct electrical wiring of biomolecules.

Recent advancements have enabled multiplexed electrochemical detection, allowing multiple analytes to be sensed simultaneously using spatially separated or electrochemically distinguishable channels. Additionally, integrating microfluidics with electrochemical lipid biosensors enables precise control of analyte delivery and real-time monitoring of dynamic biochemical processes. This makes electrochemical transduction especially suitable for point-of-care diagnostics, wearable devices, and field-deployable biosensors due to its miniaturizability, low power requirements, and real-time response capabilities [7](Siontorou et al., 2017).

Optical Detection: TOptical transduction offers a powerful approach for real-time, label-free, and high-resolution sensing using lipid membrane-based platforms. This method includes a wide range of techniques such as fluorescence spectroscopy, Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). These techniques rely on changes in optical properties—such as intensity, wavelength, or resonance frequency—caused by analyte binding or conformational shifts in membrane-embedded molecules.

Fluorescence-based methods are particularly popular due to their sensitivity and versatility. Lipid membranes can be doped with fluorescent dyes or tagged with fluorophore-conjugated ligands and receptors. Upon target binding, the resulting conformational or environmental changes can modulate fluorescence emission, enabling sensitive detection. FRET, a distance-dependent interaction between two fluorophores, allows for the detection of molecular proximity changes, making it ideal for monitoring receptor-ligand interactions or membrane fusion events.

SPR is a label-free technique that detects changes in the refractive index near the sensor surface, typically caused by biomolecular interactions at a tethered lipid membrane. It allows for kinetic analysis of binding events in real-time and is highly compatible with supported and tethered lipid bilayers. SERS enhances the Raman signal of molecules adsorbed on nanostructured metallic surfaces, providing ultrasensitive detection of analytes, including low-abundance biomarkers and toxins.

Advanced integration with microfluidics and nanophotonics has further increased the sensitivity, throughput, and multiplexing capability of optical lipid membrane biosensors. Despite their advantages, optical biosensors may require complex instrumentation and are often sensitive to environmental noise such as temperature and light fluctuations. Nevertheless, their non-invasive and real-time sensing capabilities make them invaluable in pharmaceutical screening, live-cell analysis, and diagnostics (Anderson & Han, 2021).

Mechanical Detection: Mechanical transduction methods rely on detecting physical changes in the membrane or sensor surface resulting from biomolecular interactions. These techniques often utilize micro- or nanoscale mechanical elements such as cantilevers, membranes, or surface acoustic wave (SAW) devices. When analytes interact with recognition elements embedded in the lipid membrane, changes in mass, surface stress, or viscoelastic properties occur, which can be measured with high precision.

In cantilever-based biosensors, a lipid membrane-functionalized cantilever bends in response to analyte binding, and the deflection is recorded using optical or piezoresistive readouts. SAW devices measure changes in the propagation of acoustic waves along the surface of a piezoelectric substrate due to mass loading or viscosity alterations from membrane-analyte interactions. These mechanical responses provide label-free, real-time data and are especially useful for detecting small molecule interactions, protein-lipid binding, or membrane permeability changes. Mechanical biosensors offer high sensitivity and are compatible with miniaturization, but they often require precise environmental control and sophisticated signal processing [8].In cantilever-based biosensors, a lipid membrane-functionalized cantilever bends in response to analyte binding, and the deflection is recorded using optical or piezoresistive readouts. SAW devices measure changes in the propagation of acoustic waves along the surface of a piezoelectric substrate due to mass loading or viscosity alterations from membrane-analyte interactions. These mechanical responses provide label-free, real-time data and are especially useful for detecting small molecule interactions, protein-lipid binding, or membrane permeability changes. Mechanical biosensors offer high sensitivity and are compatible with miniaturization, but they often require precise environmental control and sophisticated signal processing (Lucklum & Seifert, 2000).

Calorimetric Detection: Calorimetric biosensors detect the heat generated or absorbed during biochemical reactions or binding events occurring at the lipid membrane interface. These changes in enthalpy are measured using highly sensitive thermometric devices such as thermopiles or isothermal titration calorimeters (ITC). Lipid membranes enhance the biological relevance of calorimetric sensing by providing a native-like environment for proteins and enzymes, ensuring that the thermodynamic signatures of molecular interactions are accurately preserved.

This approach is particularly valuable for studying enzyme-substrate reactions, receptor-ligand binding, or conformational changes in membrane proteins. Although less commonly used than electrochemical or optical methods, calorimetric transduction is inherently label-free and offers rich thermodynamic data, including binding affinity, stoichiometry, and enthalpy/entropy contributions. However, calorimetric systems tend to have lower throughput and require precise thermal isolation, which can complicate integration into compact or field-deployable biosensors.

4. Applications

4.1. Medical Diagnostics

Lipid membrane biosensors have been successfully used to detect biomarkers relevant to human health:

-

Neurotransmitters: Biosensors functionalized with ion channels or neurotransmitter receptors can detect dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine with high specificity (Cornell et al., 1997). These sensors are particularly useful in neurological research and clinical diagnostics for conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease. By leveraging the real-time response of ion channel conductance, these biosensors allow for rapid monitoring of synaptic activity and drug interactions affecting neurotransmitter levels.

-

Infectious Diseases: Antibody-functionalized membranes enable detection of viral and bacterial pathogens. For instance, lipid biosensors have been developed to detect influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and tuberculosis by immobilizing pathogen-specific antibodies or antigens on the lipid interface. The biosensor’s ability to maintain a biologically relevant environment improves sensitivity and selectivity while reducing false positives. These devices can also be adapted for point-of-care diagnostics, offering rapid detection in resource-limited settings.

-

Cancer Biomarkers: Synthetic receptors and aptamers can recognize cancer-associated proteins such as PSA and HER2 [6]. These biosensors offer early detection of cancer through non-invasive or minimally invasive samples like blood or saliva. Lipid membranes enhance the functional stability of aptamers and allow multiplexed detection when combined with electrochemical or optical readouts. They are especially valuable in personalized medicine, where real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy and biomarker levels is critical.(Anderson & Han, 2021). These biosensors offer early detection of cancer through non-invasive or minimally invasive samples like blood or saliva. Lipid membranes enhance the functional stability of aptamers and allow multiplexed detection when combined with electrochemical or optical readouts. They are especially valuable in personalized medicine, where real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy and biomarker levels is critical.

-

Cardiovascular Diseases: Lipid biosensors can detect markers such as troponin I, myoglobin, and C-reactive protein (CRP), which are indicative of myocardial infarction, inflammation, or cardiac stress. By incorporating antibodies or peptide ligands into supported bilayers, these sensors provide sensitive, real-time assessment of cardiac health. Their integration into wearable devices or microfluidic chips is an emerging trend for continuous heart monitoring.

-

Metabolic Disorders: Glucose and cholesterol biosensors using enzyme-functionalized lipid membranes (e.g., glucose oxidase or cholesterol oxidase) are widely used for diabetes and lipid disorder diagnostics. The membrane environment improves enzyme performance and extends device shelf-life. These biosensors can be coupled with smartphone-based readers for user-friendly, real-time metabolic tracking.

-

Hormonal Imbalances: Biosensors targeting cortisol, insulin, thyroid hormones, or reproductive hormones are in development using receptor-modified membranes. Such sensors provide dynamic hormone profiling, which is crucial in endocrinology and fertility management. The lipid bilayer enables the incorporation of GPCRs and other hormone-binding proteins that require a native-like environment for optimal function.

4.2. Environmental Monitoring

-

Toxins and Pollutants: Enzyme-inhibited biosensors detect pesticides (e.g., organophosphates) and heavy metals by measuring disruption in membrane functionality (Siontorou et al., 2017). These toxins often act by [7]. These toxins often act by inhibiting the activity of enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which is incorporated into the lipid bilayer. Upon exposure to inhibitors like organophosphates or carbamates, enzymatic activity decreases, and the resulting change in electrical or optical signals can be correlated with toxin concentration. Heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium also interfere with membrane-associated enzymes and transport proteins. Lipid membranes provide an ideal matrix for such interactions by mimicking the biological barriers these contaminants naturally target. Some biosensors utilize metallothionein-functionalized bilayers for selective heavy metal binding. These approaches enable real-time, on-site detection of pollutants in water, soil, and air samples.inhibiting the activity of enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which is incorporated into the lipid bilayer. Upon exposure to inhibitors like organophosphates or carbamates, enzymatic activity decreases, and the resulting change in electrical or optical signals can be correlated with toxin concentration. Heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium also interfere with membrane-associated enzymes and transport proteins. Lipid membranes provide an ideal matrix for such interactions by mimicking the biological barriers these contaminants naturally target. Some biosensors utilize metallothionein-functionalized bilayers for selective heavy metal binding. These approaches enable real-time, on-site detection of pollutants in water, soil, and air samples.

-

Organic Contaminants: Lipid membranes detect phenols, surfactants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and other industrial chemicals through changes in bilayer integrity. These compounds can insert themselves into the lipid matrix, alter membrane fluidity, or cause pore formation, which in turn affects electrical properties like capacitance and ion permeability. Fluorescent probes embedded in the membrane can report changes in membrane order or polarity upon exposure to these contaminants. Surfactants, due to their amphiphilic nature, are particularly disruptive to lipid structures and can be monitored via leakage assays or impedance measurements. Biosensors targeting these compounds are crucial for monitoring industrial effluents, agricultural runoff, and urban wastewater. They offer a rapid, low-cost alternative to conventional chromatography or mass spectrometry methods.

-

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs): Lipid membrane biosensors are also being developed to detect EDCs such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and nonylphenols, which mimic or block hormonal signaling in humans and wildlife. These compounds interact with hormone receptors or lipid bilayers themselves, making them detectable through receptor-modified membranes or by observing perturbations in membrane properties. Such sensors support regulatory efforts to limit EDC exposure in food packaging, water supplies, and cosmetics.

4.3. Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Screening

Lipid biosensors are ideal for investigating membrane-drug interactions, screening ion channel modulators, and evaluating toxicity of new compounds (Tien & Ghosh, 2005). Their ability to maintain protein function in a native-like environment provides more accurate pharmacological profiling.

These biosensors provide platforms for:

-

Membrane Protein-Targeted Drug Screening: Many drug targets are embedded within cellular membranes, such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, and transporters. Lipid bilayer-based biosensors can incorporate these proteins in a functional state, enabling direct interaction studies with candidate drugs. This is crucial for screening compounds that require the membrane environment to exhibit biologically relevant binding or conformational behavior.

-

Toxicity Testing of Drug Candidates: Lipid membranes serve as a model for evaluating membrane-disruptive properties of potential drugs, excipients, or nanocarriers. Changes in bilayer integrity, ion permeability, or membrane fluidity can indicate cytotoxicity or off-target effects. This allows early-stage identification of compounds likely to cause adverse effects, reducing failure rates in later drug development stages.

-

Real-Time Monitoring of Drug-Receptor Interactions: Functionalization of lipid membranes with receptors or enzymes allows for continuous monitoring of binding kinetics, affinity, and allosteric modulation in response to drug molecules. Techniques like surface plasmon resonance (SPR), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and fluorescence assays integrated with lipid biosensors enable real-time feedback during compound testing.

-

Personalized Medicine and Drug Response Profiling: Lipid biosensors can be tailored to analyze patient-specific responses to therapeutic agents by incorporating proteins or receptors derived from patient cells. This approach supports personalized drug screening and dosing strategies based on individual biomolecular interactions.

-

Nanoparticle and Drug Carrier Assessment: The interaction between lipid membranes and drug delivery systems such as liposomes, micelles, and polymeric nanoparticles can be quantitatively assessed using biosensors. This helps evaluate targeting efficiency, fusion capability, and membrane compatibility of advanced therapeutic carriers.

Overall, lipid membrane biosensors bridge the gap between traditional in vitro assays and more physiologically relevant testing environments, offering powerful tools for efficient and predictive pharmaceutical development.

5. Advantages and Limitations

5.1. Advantages

-

Biomimicry: Offers a native-like environment for functional biomolecules. The structural and compositional similarity to natural cell membranes enhances the functional integrity of embedded proteins, enzymes, and receptors. This improves biosensor specificity, sensitivity, and biological relevance, particularly for applications involving membrane-bound proteins.

-

Versatility: Compatible with various biological recognition elements and detection modalities. Lipid membranes can be functionalized with a broad range of bioreceptors—including antibodies, aptamers, enzymes, ion channels, and synthetic ligands—making them adaptable for detecting diverse targets such as small molecules, proteins, pathogens, and environmental contaminants.

-

Miniaturization: Suitable for integration into portable, lab-on-chip platforms. Their thin, flexible structure allows for seamless incorporation into microfluidic systems and multiplexed sensor arrays. This enables high-throughput screening and field-deployable diagnostic tools that are compact, cost-effective, and scalable for mass production.

-

Real-Time Monitoring: Enables continuous and dynamic analysis of biological events (Jin [3]. The fluidic nature of lipid bilayers supports dynamic molecular interactions and fast response times, making these sensors ideal for kinetic studies, continuous analyte monitoring, and point-of-care testing.& Bai, 2020). The fluidic nature of lipid bilayers supports dynamic molecular interactions and fast response times, making these sensors ideal for kinetic studies, continuous analyte monitoring, and point-of-care testing.

-

Label-Free Detection: Many lipid biosensors utilize transduction methods such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), which do not require additional labeling. This reduces assay complexity, cost, and the risk of interfering with natural biomolecular interactions.

-

Enhanced Sensitivity: The proximity of recognition elements to transducer surfaces in supported and tethered membrane systems amplifies signal output. In systems using ion channels or enzymatic reactions, even minute concentrations of analytes can generate measurable electrical or optical responses.

-

Low Fouling and High Biocompatibility: The soft, hydrophilic nature of lipid bilayers minimizes nonspecific adsorption of proteins or contaminants, making them suitable for use in complex biological fluids such as blood, serum, or saliva. This improves sensor reliability and extends operational lifespan.

5.2 Limitations

-

Stability: Freestanding membranes like BLMs are fragile and prone to rupture. Their limited mechanical robustness and short operational lifespan restrict their use in real-world environments or prolonged measurements. Even minor physical disturbances, such as vibrations or air bubbles, can compromise membrane integrity, leading to signal loss or device failure.

-

Reproducibility: Variability in membrane formation can affect performance. The self-assembly of lipid bilayers, especially in BLMs and SLBs, can lead to inconsistent thickness, composition, or protein orientation across devices. Such inconsistencies reduce data reliability and complicate comparisons across experiments or production batches.

-

Scalability: Complex fabrication methods can hinder mass production. Techniques like Langmuir-Blodgett deposition or manual painting of membranes are labor-intensive and not easily automated. This limits large-scale deployment and increases production costs, especially for disposable or multiplexed sensor arrays.

-

Limited Long-Term Stability: Lipid membranes are susceptible to oxidation, hydrolysis, and desiccation over time, especially under ambient conditions. This degradation can impair sensor performance and storage life. Stabilizing additives or encapsulation strategies can mitigate these issues but may also impact membrane fluidity and function.

-

Protein Incorporation Challenges: Integrating functional membrane proteins into artificial bilayers requires careful control over orientation, density, and activity. Misfolded or incorrectly oriented proteins can lead to reduced sensor specificity and sensitivity. Moreover, sourcing and purifying functional membrane proteins remains technically demanding and costly.

-

Environmental Sensitivity: Lipid membranes are sensitive to changes in temperature, pH, and ionic strength, which can alter membrane phase behavior or compromise sensor performance. This poses challenges for field applications or deployment in variable environmental conditions.

6. Future Directions

The field is moving toward more robust and integrated systems through:

-

Nanomaterial Integration: Incorporating materials like graphene, carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to enhance signal amplification, membrane stability, and biorecognition efficiency (Anderson & Han, 2021). These materials provide [6]. These materials provide high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and tunable surface chemistry, which improve sensor sensitivity and enable miniaturization. Additionally, nanomaterials facilitate the anchoring of biomolecules and allow hybrid sensor architectures with synergistic properties.high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and tunable surface chemistry, which improve sensor sensitivity and enable miniaturization. Additionally, nanomaterials facilitate the anchoring of biomolecules and allow hybrid sensor architectures with synergistic properties.

-

AI and Machine Learning: Using algorithms to analyze complex biosensor data patterns in real-time. Machine learning models can deconvolute multidimensional sensor outputs, recognize patterns in dynamic biological signals, and improve the interpretation of low-signal or noisy data. AI-enabled biosensors are especially valuable in multiplexed systems, wearable health monitors, and continuous environmental surveillance, where massive data streams require rapid, automated analysis.

-

Multiplexed Platforms: Developing arrays for simultaneous detection of multiple analytes. Advances in microfabrication, droplet microfluidics, and nanoscale patterning enable high-density sensor layouts where different lipid bilayers or recognition elements are arrayed on a single chip. This supports comprehensive diagnostics, such as panels for infectious disease screening, cancer biomarker profiling, or environmental contaminant detection in a single assay.

-

Synthetic Biology Integration: Engineering novel sensing components with programmable specificity. Synthetic biology approaches allow the design of custom receptors, enzymes, or genetic circuits that function optimally in lipid membranes. These engineered components can be tailored for specific targets, tunable response kinetics, and compatibility with desired transduction methods. Biosensors leveraging synthetic elements are more modular, scalable, and adaptable to emerging threats or targets.

-

Wearable and Implantable Devices: The biocompatibility and flexibility of lipid membranes are being harnessed in the development of wearable and implantable biosensors for continuous health monitoring. These systems can non-invasively track biomarkers like sweat electrolytes, cortisol, or glucose and transmit data wirelessly to digital health platforms.

-

Self-Healing and Responsive Materials: Research into dynamic lipid membranes that self-repair or respond to environmental cues is enabling biosensors that are more durable and adaptive. Such systems could detect damage, adapt to stress, or modulate their sensitivity in response to feedback signals, extending sensor life and performance in challenging conditions.

These advancements collectively aim to overcome current limitations in stability, reproducibility, and scalability, while unlocking new functionalities and applications across healthcare, defense, agriculture, and environmental monitoring.

7. Conclusion

Lipid membrane-based biosensors represent a biologically intelligent approach to sensing, uniquely capable of hosting complex molecular interactions at the membrane interface. While technical hurdles remain, particularly in stability and mass production, ongoing innovation in materials science, nanotechnology, and bioengineering is rapidly advancing the field. These biosensors are poised to become critical tools in diagnostics, environmental safety, and drug development.

As sensor designs continue to evolve, integrating hybrid materials, artificial intelligence, and miniaturized platforms, the versatility and reliability of lipid biosensors will grow in parallel. Emerging formats—such as flexible, wearable systems and personalized diagnostic chips—highlight the adaptability of lipid membranes to next-generation health and environmental challenges. Furthermore, the increasing understanding of membrane-protein interactions and advances in synthetic biology will enable the rational design of biosensors with unprecedented specificity, speed, and multifunctionality.

In the long term, lipid membrane biosensors may play a central role in decentralized diagnostics, real-time environmental surveillance, and adaptive therapeutic monitoring. Bridging the gap between living systems and digital technologies, they exemplify a frontier in biosensor design where biology and engineering converge to deliver high-performance, responsive, and intelligent sensing solutions.

8. References

-

Sackmann, E. (1996). Supported membranes: scientific and practical applications. Science, 271(5245), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.271.5245.43

-

Tien, H. T., & Ottova-Leitmannova, A. (2003). Membrane biosensors. Progress in Surface Science, 71(1-4), 1–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6816(03)00011-3

-

Jin, Y., & Bai, Y. (2020). Recent advances in lipid membrane-based biosensors for real-time detection. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 153, 112046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2020.112046

-

Cornell, B. A., Braach-Maksvytis, V. L. B., King, L. G., Osman, P. D. J., Raguse, B., Wieczorek, L., & Pace, R. J. (1997). A biosensor that uses ion-channel switches. Nature, 387(6633), 580–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/42432

-

Anderson, M., & Han, A. (2021). Biomimetic lipid membranes for biosensing applications. ACS Sensors, 6(6), 2053–2069. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.1c00142

-

Siontorou, C. G., Nikoleli, G. P., Nikolelis, D. P., & Karapetis, S. K. (2017). Artificial lipid membranes in biosensors for environmental monitoring: A review. Sensors, 17(5), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17051173

-

Lucklum, R., & Seifert, F. (2000). Surface acoustic wave sensors. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 377(3), 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-003-2082-7

-

Tien, H. T., & Ghosh, T. K. (2005). Artificial lipid membranes: Past, present, and future. Journal of Biosciences, 30(3), 303–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02703712