This paper attempts to clarify some of the aspects and dynamics that appear particularly significant when embarking on a path that can lay the foundation for a broader reflection on the “sociology of hope”. This path will be outlined starting from the development of the concept of hope in the social sciences through an analysis of the existing literature within a specific field of study. It will continue with a systematic synthesis of those sociological studies that have led to a “dialogue” with the concept of hope and that, most often directly or indirectly, have considered hope as a force that mobilizes individuals and social groups to action. The final stage of this path will be reserved for presenting the debate that has opened in recent years around the sociology of hope, both critically and constructively, to provide recommendations for future research that, in line with this perspective, aims to study how to improve the world.

“Sociology has experienced its crises of interpretation in the crises of each society it proposes to study. The debate about sociological knowledge, the diversity of its theoretical orientations and the antagonisms that oppose one another is a debate about perspectives, ways of seeing that express ways of being. But that express also what society could supposedly be and is not. It is in this frame of reference that sociology is, in the broad sense, a science of hope that gets lost in the growing option of the sociology of the here and now, the sociology of societies where there is no longer a place for historical creation and social transformation”

This statement can be considered valid since sociology is the science capable of indicating what is historically possible. Recalling the essential elements of the concept of hope, which are linked precisely to what is possible, sociology can be a sociology of hope because it is a science capable of orienting and guiding change.

If it is well-known what sociology is, what is meant by hope beyond the idea of common sense is less well-known. Before delving, therefore, into this path of systematic reflection on the “sociology of hope”—something that sociologists until a few years ago had not even attempted to develop

[2], despite the notion that “hope has been and still is an essential element of human existence”

[3] (p. 7)—it is necessary to discuss some of the more peculiar characteristics of hope through some stages of human history that will quickly take us from mythology to our contemporary times, highlighting those aspects and dynamics common to it.

In Greek mythology, hope is conceived both as a “longing for good” and a “counteraction to the evils of the world”, while also looking to the future. According to the story told by Hesiod in his works “The Theogony” and “Works and Days” (dating back to the 8th century BC), after Prometheus stole fire to give it to mankind (a source of ingenuity and innovation), Zeus unleashed his vengeance on all mankind. To carry out his plan, he gave Pandora (Πανδωρα)—etymologically, from the Greek, and from the roots παν (

pan, “all”) and δωρον (

doron, “gift”)—wife of the brother of Prometheus (Epimetheus), a

píthos (large earthenware jar)—generally translated into English with the word box

[4]—in which all the evils of the world were locked. He recommended not opening it until the end of her days. Pandora, curious and prompted by the gods, opened the box, and all the evils were spread throughout the world. According to the myth, this was when the problems for men began. Pandora managed to put the lid back on the jar by the will of Zeus. At the bottom, there remained only

Elpís (ἐλπίς, literally, the personification of hope) who was unable to escape. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, however, hope, for individuals, is considered a positive and active expectation (motivation to act positively), placing trust in the success of a project’s objective or having confidence in the successful outcome of a project. With the sacred aura of the Middle Ages, on the gates of Hell—in Dante’s most important work—we read, “

Lasciate ogne speranza,

voi ch’

intrate” (Abandon all hope, ye who enter!)

[5] (Vol. 1, Canto III, 9). This exemplifies the condition that awaits the damned, which is characterized by the absolute denial of the expectation of good (salvation). Considering the latest pontificates, this perspective is confirmed; Benedict XVI

[6] dedicates an entire encyclical (Spe Salvi) to hope, which is considered almost interchangeable with the virtue of faith so much so as to describe it as a performative process, capable of producing facts and changing life. Pope Francis for the Jubilee of 2025 chose “

Pilgrims of Hope” as its motto

[7], given that it was a Jubilee Year proclaimed to foster the restoration of a climate of trust after the COVID−19 pandemic since, in absolute terms, hope translates into the “confident expectation of something good”. Finally, moving from faith to earthly aspects, there is also the motto of the World Social Forum (WSF), “Another world is possible”

[8], which “embodied” hope very well since it makes human action fall within the “logic of the possible”—“Not-Yet-Conscious” but “being-in-possibility”. As Bloch

[9] argued by overcoming the logic of the

hic et nunc, hope is no longer just a social construct but rather a complex personal and social experience.

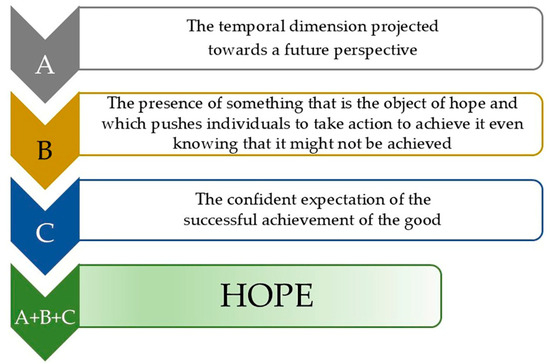

The elements common to all the ideas of hope (Figure 1) that have spread throughout human history are visible and can be summarized as (A) the temporal dimension projected towards a future perspective; (B) the presence of something that is the object of hope and which pushes individuals to take action to achieve it even knowing that it might not be achieved; and (C) the confident expectation of the successful achievement of the good.

Figure 1. The elements common to all the ideas of hope.

But why talk about the “sociology of hope” in the 21st century? Because, if it is true, as we shall see, that hope is an ontological need of human beings, there are moments in history when the need to hope appears even stronger, and never more so than in today’s society, which seems to be moving from the economic crisis of 2008 and its consequences to the pandemic caused by the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, from the ecological and migration crisis to recent conflicts and to the challenges and threats of the development of artificial intelligence. Fears of the destruction of humanity and the universe have regained strength, and depression and pessimism have become salient features of the social character of our time. For this reason, perhaps today it is useful to revisit the theme of hope and, in particular, a ‘sociology of hope’, since in recent years this discipline has focused too much on the idea of permanent crisis, on the weakness and fragmentation of social bonds, the fluidity of relationships, and the contingency and reversibility of all values. Sociology must “go beyond”—without renouncing its component of analysis and social criticism—and seek out social and cultural experiences that are experiences of solidarity, reciprocity, social creativity, and planning, in other words, of hope. That hope is a complex personal and social experience in terms of the category of “possibility” and, therefore, of the idea that “Another world is possible”.