Nematodes of the Anisakidae family have a cosmopolitan distribution, due to their ability to infest a wide variety of aquatic hosts during the development of their larval stages, mainly marine mammals and aquatic birds, such as pelicans; being the hosts where the life cycle is completed. The participation of intermediate hosts such as cephalopods, shrimp, crustaceans and marine fish, are an important part to complete this cycle. However, its importance in human health is due to its zoonotic capacity, which causes the clinical presentation in humans, known as Anisakiasis or Anisakidosis, depending on the species of the infecting parasite.

- anisakiasis,anisakidosis,Anisakidae,parasite, fish

1. Introduction

Transmission of diseases to humans caused mainly by the consumption of fish or fishery products is known as ichthyozoonosis[3] [1]. These diseases are of bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic etiology. Parasitic ichthyzoonoses are highly relevant, due to the severe clinical conditions that they can cause in humans[4] [2].

One of the main families of parasites that have the ability to cause parasitic ichthyozoonosis is the Anisakidae family, which belongs to the phylum Nematoda and class Secernentea and the order Ascaridida, suborden Ascaridina, superfamily Ascaridoidea, family Anisakidae[5][6] [3,4]. The nematodes of the Anisakidae family are distributed in a cosmopolitan way[7] [5] and the family is made up of different genera, some of them with great zoonotic potential, such as the genus Anisakis[8][9] [6,7]. For the development of the biological cycle of the parasite, the participation of marine fish is important, as they act as paratenic hosts or carriers of the L3 larval stage, where the larvae encyst or remain attached to the internal tissues[8] [6]. The parasite has the ability to remain in the coelomic cavity or carry out larval migration to the epiaxial muscle of the infested fish; the life cycle is completed when the marine mammal and piscivorous birds consumes the paratenic host[10][11] [8,9].

Acquisition of the parasite in humans occurs through the consumption of raw or semi-raw fish or marine products. Due to different existing cultural and gastronomic traditions, in the case of Mexico, the infection is acquired by the consumption of dishes such as aguachile or the popular ceviche [10][8], while in other countries, such as Japan, the consumption of dishes such as sushi and sashimi favor the presentation of parasitic ichthyozoonosis; in the Asian continent the average consumption of fishery products is 24 kg per year[12][13][14] [10,11,12]. The clinical disease caused by these parasites is known as “anisakiasis”, when the infection is caused by the species A. simplex sensu stricto (s.s.), or “anisakidosis” when the infection is caused by Contracaecum spp. or Pseudoterranova spp.[15][16] [13,14].

The clinical symptoms are nonspecific and may present as epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention with intense pain and sometimes hypersensitivity reactions[15] [13]. The development of molecular tests and genetic sequencing in the clinical field has allowed the correct identification of the different parasitic species related to clinical pictures, and that in turn allows understanding of the individually pathologies to which each of these genus are related[17] [15]. On the other hand, the use of molecular tests has allowed the maintenance and/or discard of the parasitic genera that have been described morphologically, allowing clarification of which members really belong to the Anisakidae family. Based on the above, the purpose of this work was to carry out a bibliographic search of the genus and species that have been described in the Anisakidae family, identified by the use of morphological and molecular test; as well only through the use of molecular tests and the hosts that have been collected.

2. Life Cycle

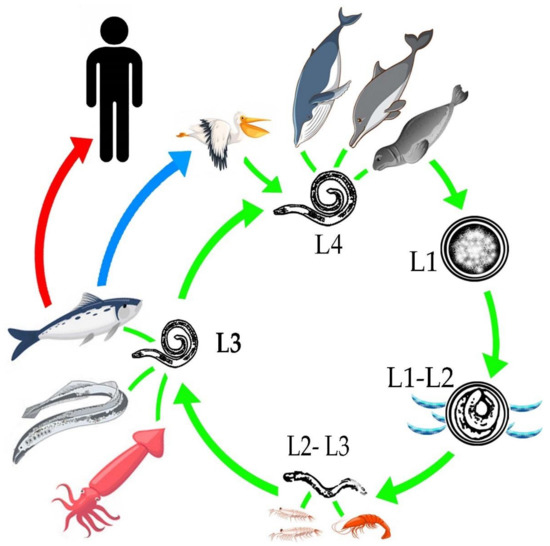

Anisakarid nematodes have the ability to infest a wide variety of aquatic organisms during the development of their different stages, from egg to an adult capable of reproduction[18] [16]. The adult stages are observed in the definitive hosts, such as marine mammals, among which are whales, belugas, dolphins, sea bears and seals [19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]; as well as in different species of birds such as pelicans, penguins and herons [25][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

To understand the life cycle of the parasite it is important to know that there are four larval stages, larvae 4 (L4) are males, and females. The females are capable of producing 1.5 million eggs. Oviposition increases in the last phase of life of the female, which is estimated to be at 30 to 60 days old[39] [37]. The embryonated eggs are released into the intestine of the definitive hosts[40] [38] and are eliminated through the feces to the aquatic environment, where the larval stages L1 and L2 develop[11] [9]. It is important to mention that hatching does not occur in the digestive tract of marine mammals, due to temperature, since the action of other external requirements, such as low sea temperatures, salinity and the presence of oxygen favor the hatching of the egg[39] [37]. In the sea, the egg with L2, will mix with plankton, krill, copepods and small crustaceans[40][41] [38,39]. An important key of the Anisakidae family, to adapt and infest different hosts, radiate in the infestation of different organisms that are part of the trophic links of marine ecosystems from merozooplankton, like Nyctiphanes couchii (Euphausiacea) or Sapa fusiformis (Salpidae), just to mention a few; up to infest the top predators of importance for the life cycle[41] [39]. The L2 uses these copepods to ingest it and release L2, L2 remains inside of these intermediate hosts until it reaches an optimal size for its molt to L3[42] [40], unless they are consumed by fish[43] [41]. When marine fish consume the intermediate hosts, they act as paratenic hosts or carriers of stage L3 [11][9], which is trapped in the gastrointestinal tract and migrates toward the coelomic cavity; being free, it encysts in internal tissues such as liver, kidney and epiaxial muscle[44][45] [42,43] or adheres to the serosa of internal tissues [8][10][6,8], causing an inflammatory response[11] [9]. The life cycle of the parasite is completed when the fish infested with L3 is ingested by marine mammals where the larval stage L4, or the adult form, develops[11] [9]. In birds, when they consume the infested fish, during the digestion process the L3 is released and the parasite is free to make its last molt, transforming into L4 and repeating the life cycle[42][45] [40,44]. It is important to mention that L3 does not have the ability to develop to L4 in fish and humans, so parasitic reproduction in them does not take place[43] [41] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General life cycle of the Anisakidae family.

3. Anisakiosis/Anisakiasis

Parasitic ichthyozoonosis caused by some genus of the Anisakidae family can be acquired by humans through the consumption of different poorly cooked, semi-raw and raw marine animals, such as fish, squid, marine mollusks and octopus, among others[15] [13]. Likewise, the different eating habits of a particular area and/or the acquisition of these habits in new geographical areas can result from the globalization of gastronomy[12] [10]. The existence of culinary dishes where the fish is eaten raw or semi-raw includes sushi, sashimi, tuna tartare, herring and pickled anchovies; ceviche, tiradito smoked or salted herring; gravlax or thin, thin cuts of Scandinavian salmon meat; Spanish anchovies in vinegar (pickled anchovies); raw sardines, kuai, kokoda, kelaguen, fish tripe, among others[8][9][13][3] [6,7,11,133].

The consumption of fish infested with the larval stage L3 causes the disease known as “anisakidosis”, which refers to the disease produced by A. pegreffi[46] [78], Contracaecum osculatum[47] [43], Pseudoterranova azarazi [48][49] [134,135], P. cattani [29][50] [26,136], P. decipiens [43] [45] and P. krabbei [51] [110]. While the term “anisakiosis” refers to the pathology caused specifically by the species Anisakis simplex s.s. [9][16][17][21][22][52][53][7,14,15,19,20,52,89]. One of the peculiarities of A. simplex s.s. is its ability to migrate more frequently to the epiaxial muscles of the fish, due to its high adaptability and physiological tolerance, which is why it tends to be more frequent in clinical cases in humans[54] [82]; it also increases the risk of developing “anisakiosis” [16][17][13,14]. Likewise, it has been observed that infections caused by P. decipiens tend to be less invasive compared to those caused by A. simplex s.s., as well as the absence of severe gastric signs in reported cases for P. cattani [55] [137] and P. azarasi, which have been collected from the palatine tonsillar[48] [134]. When humans become accidental hosts, the parasite can survive for a short period of time without the ability to develop into adulthood and reproduce[48] [138].

The first signs of the disease may present as a sensation of having something between the teeth, respiratory symptoms and nasal congestion, “tingling throat syndrome”, epigastralgia, nausea, gastric reflux, cough, dysphagia, vomiting and in some cases hematemesis has been reported due to gastric ulceration, depending on the location of the parasite[28][48][56][55] [26,122,124,137,138].

The pathogenicity of anisakiosis/anisakiasis results from two main mechanisms: (1) direct tissue damage, and (2) an allergic response. Likewise, four categories have been determined in which the zoonotic species of the Anisakidae family can cause a clinical picture: (1) gastric, which occurs more frequently [57][126]; (2) intestinal[58] [122]; (3) ectopic or extra-intestinal, where larval migration to the abdominal cavity occurs[58] [122]. Likewise, there may be extraordinary cases where the parasite can encyst in the esophagus, causing eosinophilic esophagitis[59] [121] and palatine tonsillar infection [48][134]; and (4) the generation of allergies [60][116]. Anisakiasis can be present as an asymptomatic, acute (or subacute) symptomatic or chronic symptomatic disease[61] [118]. Once the body comes into contact with the parasite, different degrees of inflammatory responses develop, as well as changes in the permeability of blood vessels[62][63] [139,140]. The body can react by developing granulomas in the submucosa, with abundant eosinophilic infiltrate (eosinophilic granuloma) and the presence of edema at the site of injury[11][64] [8,141]. The survival capacity of the larva in humans is 2 to 3 weeks after being ingested[61][65] [118,123].

It has been determined that the difference between gastric and intestinal presentation lies in the time since the raw shellfish was consumed, these being 7 and 36 h, respectively[65] [123]. Some authors consider that the manifestation of the disease can occur in a period of 7 to 12 h after consumption of the parasite[8] [6,137]. In approximately 95% of clinical cases, the larva can penetrate the gastric mucosa [50][136] and be observed with relative ease anchored and manifesting epigastric pain in the host until the larva dies or is surgically removed[66] [142]. When the presentation is intestinal, it can cause abdominal distention and intense pain in the patient, which can be present for 5 to 7 days [14][13]. The presence of edema and abscesses in the mucosa and submucosa have been described, with a marked eosinophilic response around the larvae in the duodenum, jejunum[62] [139] ileum and colon[67] [143]. The main microscopic findings at the site of the injury are characterized by the presence of moderate to severe eosinophilic infiltrate and erosion of the mucosa [68][144]. Encystment has also been observed in the intestinal epithelium that can trigger the presentation of cancer; however, this will depend on the mutagenicity of the cells and the tumor-promoting potential of larval antigens[1] [145]. In a study carried out by Murata et al.[69] [115], a case of hepatic anisakidosis caused by P. decipiens was reported, which was first diagnosed in the patient as a neoplasm; however, when analyzing the tumor, it was identified that it was an eosinophilic granuloma, in which the larva was located at the center of the lesion.

The allergic response is caused by 28 allergens, among which is found proteins with antigenic roles, excretory secretory products and enzymes, that have been identified in A. simplex s.s. and A. pegreffii [70] [71] among which are somatic and secretory antigens released by the larva when surgically removed, expelled by the body or when it dies within the body[64] [141]. The main allergen recognized by the human body is the serum protein Ani s 1, identified in 87% of patients who develop the clinical picture, where previously fish infested with the nematode have been consumed [71][146]; Ani s 7 is an excretory antigen that has not been well characterized but is detected in 100% of patients with allergy caused by the parasite, during the acute phase of infection[70] [71,147]; and Ani s 4, which is a cysteine detected in 27–30% of patients[72] [147]. Many of these allergens are resistant to heat and/or pepsin; however, the most recognized by patients is the protein Ani s 1, a serine protease inhibitor that is heat stable and remains present even when the fish is cooked [73][148]. In the case of A. pegreffii, 2 antigenic proteins have been identified, which have the role of secretion products, being A.peg-1 and A.peg-13 which are expressed by the parasite when the temperature of the environment where the parasite ranges from 20 to 37 °C, respectively; for Contracaecum rudolphii, it has an enzymatic activity, among which are the activities of hydrolases that cause damage to the epithelium of the digestive tract, which allows the parasite to migrate freely in the host[70] [71]. The clinical manifestations of an allergy can be moderate, when the presentation can manifest as irritation, inflammation, ulceration, secondary gingivostomatitis in the areas that have been in contact with the larva[74] [149] and urticaria, which occurs in 60–70% of cases where there is a gastric presentation [8][75][7,150]; or severe, when a type I hypersensitivity reaction occurs, which can cause the presentation of angioedema, hypotension, bronchospasms, the presentation of anaphylactic shock and even asthma or worsening of a previous asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, bronchoconstriction and dermatitis, without an acute infectious picture being present [76][77][125,140,141,142,148,151,152]. The presentation of the allergy caused by Anisakis spp. is more prevalent than other food allergies in adult humans, which includes 10% of idiopathic anaphylactic reactions[77] [152].

It has been suggested that, to correlate the nonspecific clinical manifestations caused by Anisakidosis/anisakiasis, it is necessary to associate the information from the medical history, where information on the consumption of foods of marine origin, raw, semi-raw, pickled or other preparation[1] [145]. However, due to the complexity of the clinical presentation, Anisakidosis/Anisakiasis are misdiagnosed, and can be confused with other conditions, such as appendicitis, gastric ulcer, tumors, cholecystitis, peritonitis, Crohn’s colitis, diverticulitis, intestinal intussusception, abdominal obstruction, appendicitis and peptic ulcers, also food allergies, bacterial and viral gastrointestinal infections; and even other intestinal parasites [78][59[106,121,133,153][3][79]. Some of the complications that can occur along with parasitic infection include intestinal obstruction, eosinophilic enteritis, spontaneous rupture of the spleen [80][154], presentation of eosinophilic granuloma, marked eosinophilia and abdominal distension[2] [155].

Gastroscopy in the first stages of the disease allows to observe the mucosa and the presence of the parasite in situ, the use of computed tomography has been very useful to observe the area with the inflammatory process, which would suggest the presence of the parasite[65] [123]. One of the cellular manifestations that have accompanied the infestation caused by Anisakis spp is the presentation of infiltrate and degranulation of the eosinophils, in the site where the parasite is found, this in turn also generates misdiagnosis problems, etiological agents such as Baylisascaris procyonis, Gnathostoma spp., Echinocephalus spp., among others can generate a similar cellular reaction [133,145,155], when the parasite is found in the intestinal tract, surgeries are performed to collect the parasite[81] [156].

The ability of this parasite to adapt to different hosts allows the Anisakidae family to be collected in different sea animals and should be considered as a natural event throughout the life cycle of the Anisakidae family and not as a contaminating agent on fishery products[70] [71]. As a natural event, it is important that humans know about its existence and the different ways of preventing infestation, through food safety and sanitary measures, as well as education for people about preventing disease[1] [1]. In addition, very important medical staff must be updated on Anisakiosis/Anisakiasis to consider it as a possible diagnosis, using specific diagnostic tests that allow the correct identification of the etiological agent and, if the medical staff does not have experience with seafood parasites, approach an expert[82][3][83] [129,133,157].

Reference (we'll rearrange the references after you submitted it)

- Castellanos-Monroy, J.A.; Daschner, A.; Putostovrh, M.; Cuellar, C. Characteristics related to fish consumption and the risk of ichthyozoonosis in a Colombian population. Rev. Salud Pública 2020, 21, e169898.

- Monroy, G.C.; Santamaría, M.A.; Toméa, I.C.; Mayoralas, M.V.P. Gastritis aguda por anisakis. Rev. Clin. Med. Fam. 2014, 7, 56–58.

- Shamsi, S.; Barton, D.P.; Zhu, X. Description and genetic characterisation of Pulchrascaris australis n. sp. in the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini (Griffin & Smith) in Australian waters. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 1729–1742.

- Murata, R.; Suzuki, J.; Sadamasu, K.; Kai, A. Morphological and molecular characterization of Anisakis larvae (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Beryx splendens from Japanese waters. Parasitol. Int. 2011, 60, 193–198.

- Anderson, R.C. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1992.

- Ferrantelli, V.; Costa, A.; Graci, S.; Buscemi, M.D.; Giangrosso, G.; Porcarello, C.; Palumbo, S.; Cammilleri, G. Anisakid Nematodes as Possible Markers to Trace Fish Products. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2015, 4, 4090.

- Laffon–Leal, S.M.; Vidal–Martínez, V.M.; Arjona–Torres, G. ‘Cebiche’––A potential source of human anisakiasis in Mexico? J. Helminthol. 2000, 74, 151–154.

- Mattiucci, S.; Paoletti, M.; Borrini, F.; Palumbo, M.; Palmieri, M.R.; Gomes, V.; Casati, A.; Nascetti, G. First molecular identification of the zoonotic parasite Anisakis pegreffii (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in a paraffin–embedded granuloma taken from a case of human intestinal anisakiasis in Italy. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 82.

- Castellanos, J.A.; Tangua, A.R.; Salazar, L. Anisakidae nematodes isolated from the flathead grey mulletfish (Mugilcephalus) of Buenaventura, Colombia. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites. Wildl. 2017, 6, 265–270.

- Grano-Maldonado, M.I.; Medina-Vera, R.A. Parasitosis, gastronomic tourism and food identities: A public health problem in Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México. Neotrop. Helminthol. 2019, 13, 203–225.

- Tokiwa, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ike, K.; Morishima, Y.; Sugiyama, H. Detection of Anisakid Larvae in Marinated Mackerel Sushi in Tokyo, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 71, 88–89.

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229es/ca9229es.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Ahmed, M.; Ayoob, F.; Kesavan, M.; Gumaste, V.; Khalil, A. Gastrointestinal Anisakidosis—Watch What You Eat. Cureus 2016, 8, e860.

- Bao, M.; Pierce, G.J.; Pascual, S.; González-Muñoz, M.; Mattiucci, S.; Mladineo, I.; Cipriani, P.; Bušelić, I.; Strachan, N.J. Assessing the risk of an emerging zoonosis of worldwide concern: Anisakiasis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43699.

- Roca-Geronès, X.; Alcover, M.M.; Godínez-González, C.; González-Moreno, O.; Masachs, M.; Fisa, R.; Montoliu, I. First Molecular Diagnosis of Clinical Cases of Gastric Anisakiosis in Spain. Genes 2020, 11, 452.

- Di Azevedo, M.I.N.; Carvalho, V.L.; Iñiguez, A.M. Integrative taxonomy of anisakid nematodes in stranded cetaceans from Brazilian waters: An update on parasite’s hosts and geographical records. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 3105–3116.

- Quiazon, K.M.; Santos, M.D.; Yoshinaga, T. Anisakis species (Nematoda: Anisakidae) of Dwarf Sperm Whale Kogia sima (Owen, 1866) stranded off the Pacific coast of southern Philippine archipelago. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 197, 221–230.

- Mladineo, I.; Hrabar, J.; Vrbatović, A.; Duvnjak, S.; Gomerčić, T.; Duras, M. Microbiota and gut ultrastructure of Anisakis pegreffii isolated from stranded cetaceans in the Adriatic Sea. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 381.

- Kuzmina, T.A.; Lyons, E.T.; Spraker, T.R. Anisakids (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from stomachs of northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus) on St. Paul Island, Alaska: Parasitological and pathological analysis. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 4463–4470.

- Najda, K.; Simard, M.; Osewska, J.; Dziekońska-Rynko, J.; Dzido, J.; Rokicki, J. Anisakidae in beluga whales Delphinapterus leucas from Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2015, 115, 9–14.

- D’Amelio, S.; Mathiopoulos, K.D.; Santos, C.P.; Pugachev, O.N.; Webb, S.C.; Picanço, M.; Paggi, L. Genetic markers in ribosomal DNA for the identification of members of the genus Anisakis (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea) defined by polymerase-chain-reaction-based restriction fragment length polymorphism. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000, 30, 223–226.

- Shamsi, S.; Suthar, J. Occurrence of Terranova larval types (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Australian marine fish with comments on their specific identities. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1722.

- Shamsi, S.; Norman, R.; Gasser, R.; Beveridge, I. Redescription and genetic characterization of selected Contracaecum spp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from various hosts in Australia. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 104, 1507–1525.

- Pantoja, C.S.; Borges, J.N.; Santos, C.P.; Luque, J.L. Molecular and Morphological Characterization of Anisakid Nematode Larvae from the Sandperches Pseudopercis numida and Pinguipes brasilianus (Perciformes: Pinguipedidae) off Brazil. J. Parasitol. 2015, 101, 492–499.

- Timi, J.T.; Paoletti, M.; Cimmaruta, R.; Lanfranchi, A.L.; Alarcos, A.J.; Garbin, L.; George-Nascimento, M.; Rodríguez, D.H.; Giardino, G.V.; Mattiucci, S. Molecular identification, morphological characterization and new insights into the ecology of larval Pseudoterranova cattani in fishes from the Argentine coast with its differentiation from the Antarctic species, P. decipiens sp. E (Nematoda: Anisakidae). Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 199, 59–72.

- Weitzel, T.; Sugiyama, H.; Yamasaki, H.; Ramirez, C.; Rosas, R.; Mercado, R. Human Infections with Pseudoterranova cattani Nematodes, Chile. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1874–1875.

- Tanzola, R.D.; Sardella, N.H. Terranova galeocerdonis (Thwaite, 1927) (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from Carcharias taurus (Chondrichthyes: Odontaspididae) off Argentina, with comments on some related species. Syst. Parasitol. 2006, 64, 27–36.

- Tavares, L.E.; Saad, C.D.; Cepeda, P.B.; Luque, J.L. Larvals of Terranova sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) parasitic in Plagioscion squamosissimus (Perciformes: Sciaenidae) from Araguaia River, State of Tocantins, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2007, 16, 110–115.

- Mattiucci, S.; Paoletti, M.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Baldiris, R.; Arroyo-Salgado, B.; Garbin, L.; Navone, G.; Nascetti, G. Contracaecum bioccai n. sp. from the brown pelican Pelecanus occidentalis (L.) in Colombia (Nematoda: Anisakidae): Morphology, molecular evidence and its genetic relationship with congeners from fish—Eating birds. Syst. Parasitol. 2008, 69, 101–121.

- D’Amelio, S.; Cavallero, S.; Dronen, N.O.; Barros, N.B.; Paggi, L. Two new species of Contracaecum Railliet & Henry, 1912 (Nematoda: Anisakidae), C. fagerholmi n. sp. and C. rudolphii F from the brown pelican Pelecanus occidentalis in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Syst. Parasitol. 2012, 81, 1–16.

- Mattiucci, S.; Paoletti, M.; Solorzano, A.C.; Nascetti, G. Contracaecum gibsoni n. sp. and C. overstreeti n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from the Dalmatian pelican Pelecanus crispus (L.) in Greek waters: Genetic and morphological evidence. Syst. Parasitol. 2010, 75, 207–224.

- Garbin, L.E.; Diaz, J.I.; Navone, G.T. Species of Contracaecum parasitizing the Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus (Spheniscidae) from the Argentinean Coast. J. Parasitol. 2019, 105, 222–231.

- Molina-Fernández, D.; Valles-Vega, I.; Hernández-Trujillo, S.; Adroher, F.J.; Benítez, R. A scanning electron microscopy study of early development in vitro of Contracaecum multipapillatum s.l. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) from the Gult of California, Mexico. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 2733–2740.

- Pekmezci, G.Z. Occurrence of Anisakis pegreffii (Nematoda: Anisakidae) Larvae in Imported John Dory (Zeus faber) from Senegalese Coast Sold in Turkish Supermarkets. Acta Parasitol. 2019, 64, 582–586.

- Garbin, L.E.; Mattiucci, S.; Paoletti, M.; Diaz, J.I.; Nascetti, G.; Navone, G.T. Molecular identification and larval morphological description of Contracaecum pelagicum (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from the anchovy Engraulis anchoita (Engraulidae) and fish–eating birds from the Argentine North Patagonian Sea. Parasitol. Int. 2013, 62, 309–319.

- Borges, J.N.; Santos, H.L.; Brandão, M.L.; Santos, E.G.; De-Miranda, D.F.; Balthazar, D.A.; Luque, J.L.; Santos, C.P. Molecular and morphological characterization of Contracaecum pelagicum (Nematoda) parasitizing Spheniscus magellanicus (Chordata) from Brazilian waters. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2014, 23, 74–79.

- Ugland, K.I.; Strømnes, E.; Berland, B.; Aspholm, P.E. Growth, fecundity and sex ratio of adult whaleworm (Anisakis simplex; Nematoda, Ascaridoidea, Anisakidae) in three whale species from the North–East Atlantic. Parasitol. Res. 2004, 92, 484–489.

- Smith, J.W. Anisakis simplex (Rudolphi, 1809, det. Krabbe, 1878) (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea): Morphology and morphometry of larvae from euphausiids and fish, and a review of the 1ife–history and ecology. J. Helminthol. 1983, 57, 205–224.

- Gregori, M.; Roura, Á.; Abollo, E.; González, Á.F.; Pascual, S. Anisakis simplex complex (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in zooplankton communities from temperate NE Atlantic waters. J. Nat. Hist. 2015, 49, 13–14.

- Køie, M.; Fagerholm, H.P. The life cycle of Contracaecum osculatum (Rudolphi, 1802) sensu stricto (Nematoda, Ascaridoidea, Anisakidae) in view of experimental infections. Parasitol. Res. 1995, 81, 481–489.

- Valles-Vega, I.; Molina-Fernández, D.; Benítez, R.; Hernández-Trujillo, S.; Adroher, F.J. Early development and life cycle of Contracaecum multipapillatum s.l. from a brown pelican Pelecanus occidentalis in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2017, 125, 167–178.

- Reyes, R.N.E.; Vega, S.V.; Gómez-de Anda, F.R.; García, R.P.B.; González, R.L.; Zepeda-Velázquez, A.P. Species of Anisakidae nematodes and Clinostomum spp. infecting lisa Mugil curema (Mugilidae) intended for human consumption in Mexico. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2020, 29, e017819.

- Mehrdana, F.; Bahlool, Q.Z.M.; Skov, J.; Marana, M.H.; Sindberg, D.; Mundeling, M.; Overgaard, B.C.; Korbut, R.; Strøm, S.B.; Kania, P.W.; et al. Occurrence of zoonotic nematodes Pseudoterranova decipiens, Contracaecum osculatum and Anisakis simplex in cod (Gadus morhua) from the Baltic Sea. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 205, 581–587.

- Nemeth, N.M.; Yabsley, M.; Keel, K. Anisakiasis with proventricular perforation in a greater shearwater (Puffinus gravis) off the coast of Georgia, USA. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2012, 43, 412–415.

- Berland, B. Nematodes from some Norwegian marine fishes. Sarsia 1961, 2, 1–50.

- Shamsi, S.; Ghadam, M.; Suthar, J.; Mousavi, H.E.; Soltani, M.; Mirzargar, S. Occurrence of ascaridoid nematodes in selected edible fish from the Persian Gulf and description of Hysterothylacium larval type XV and Hysterothylacium persicum n. sp. (Nematoda: Raphidascarididae). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 7, 265–273.

- Mašová, S.; Baruš, V.; Seifertová, M.; Malala, J.; Jirků, M. Redescription and molecular characterisation of Dujardinascaris madagascariensis and a note on D. dujardini (Nematoda: Heterocheilidae), parasites of Crocodylus niloticus, with a key to Dujardinascaris spp. in crocodilians. Zootaxa 2014, 3893, 261–276.

- Grabda, J. Studies on the life cycle and morphogenesis of Anisakis simplex (Rudolphi, 1809) (Nematoda: Anisakidae) cultured in vitro. Acta. Ichthyol. Piscat. 1976, 6, 119–141.

- Baptista-Fernandes, T.; Rodrigues, M.; Castro, I.; Paixão, P.; Pinto-Marques, P.; Roque, L.; Toscano, C. Human gastric hyperinfection by Anisakis simplex: A severe and unusual presentation and a brief review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 38–41.

- Wharton, D. Nematode eggshells. Parasitology 1980, 81, 447–463.

- Moravec, F. Nematodes of Fresh Water Fishes of the Neotropical Region; Academia: Praha, Czech Republic, 1998; Volume 464.

- Pérez-i-García, D.; Constenla, M.; Carrassón, M.; Montero, F.E.; Soler-Membrives, A.; González–Solís, D. Raphidascaris (Raphidascaris) macrouri n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from two deep-sea macrourid fishes in the Western Mediterranean: Morphological and molecular characterisations. Parasitol. Int. 2015, 64, 345–352.

- Moravec, F.; Thatcher, V.E. Raphidascaroides brasiliensis n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae), an intestinal parasite of the thorny catfish Pterodoras granulosus from Amazonia, Brazil. Syst. Parasitol. 1997, 38, 65–71.

- Moravec, F.; Jirků, M. Dujardinascaris mormyropsis n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from the osteoglossiform fish Mormyrops anguilloides (Linnaeus) (Mormyridae) in Central Africa. Syst. Parasitol. 2014, 88, 55–62.

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Tu, G.; Tang, X.; Wu, X. Preliminary report on the intestinal parasites and their diversity in captive Chinese alligators. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 31, 813–819.

- Téllez, M.; Nifong, J. Gastric nematode diversity between estuarine and inland freshwater populations of the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis, daudin 1802), and the prediction of intermediate hosts. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2014, 3, 227–235.

- Junker, K.; Boomker, J.; Govender, D.; Mutafchiev, Y. Nematodes found in Nile crocodiles in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, with redescriptions of Multicaecum agile (Wedl, 1861) (Heterocheilidae) and Camallanus kaapstaadi Southwell & Kirshner, 1937 (Camallanidae). Syst. Parasitol. 2019, 96, 381–398.

- Gamal, R.; Hassan, T. Morphological Characterization of Dujardinascaris Spp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from the Striped Red Mullet Mullus Surmuletus in the Mediterranean Sea. Helminthologia 2019, 56, 338–346.

- Moravec, F.; Kohn, A.; Fernandes, B.M. Two new species of the genus Goezia, G. brasiliensis sp. n. and G. brevicaeca sp. n. (Nematoda: Anisakidae), from freshwater fishes in Brazil. Folia Parasitol. 1994, 41, 271–278.

- Martins, L.M.; Yoshitoshi, E.R. A new nematode species Goezia leporini n. sp. (Anisakidae) from cultured freshwater fish Leporinus macrocephalus (Anostomidae) in Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 2003, 63, 497–506.

- El Alfi, N.M. The nematode Goezia sp. (Anisakidae) from Bagrus bayad (Osteichthyes) from Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 205–211.

- Akther, M.; Alam, A.; D’Silva, J.; Bhuiyan, A.I.; Bristow, G.A.; Berland, B. Goezia bangladeshi n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from an anadromous fish Tenualosa ilisha (Clupeidae). J. Helminthol. 2004, 78, 105–113.

- Jackson, G.J.; Bier, J.W.; Payne, W.L.; Gerding, T.A.; Knollenberg, W.G. Nematodes in Fresh Market Fish of the Washington, D.C. Area. J. Food Prot. 1978, 41, 613–620.

- Silva, M.T.D.; Cavalcante, P.H.O.; Camargo, A.C.A.; Chagas-Moutinho, V.A.D.; Santos, E.G.N.D.; Santos, C.P. Integrative taxonomy of Goezia spinulosa (Nematoda: Raphidascarididae) from arapaimas in the northwestern Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 242, 14–21.

- Pereira, F.B.; Luque, J.L. An integrated phylogenetic analysis on ascaridoid nematodes (Anisakidae, Raphidascarididae), including further description and intraspecific variations of Raphidascaris (Sprentascaris) lanfrediae in freshwater fishes from Brazil. Parasitol. Int. 2017, 66, 898–904.

- Shamsi, S.; Gasser, R.; Beveridge, I. Description and genetic characterisation of Hysterothylacium (Nematoda: Raphidascarididae) larvae parasitic in Australian marine fishes. Parasitol. Int. 2013, 62, 320–328.

- Malta, L.S.; Paiva, F.; Elisei, C.; Tavares, L.E.R.; Pereira, F.B. A new species of Raphidascaris (Nematoda: Raphidascarididae) infecting the fish Gymnogeophagus balzanii (Cichlidae) from the Pantanal wetlands, Brazil and a taxonomic update of the subgenera of Raphidascaris based on molecular phylogeny and morphology. J. Helminthol. 2018, 94, e24.

- Moravec, F.; Justine, J.L. New records of anisakid nematodes from marine fishes off New Caledonia, with descriptions of five new species of Raphidascaris (Ichthyascaris) (Nematoda, Anisakidae). Parasite 2020, 27, 20.

- Cavallero, S.; Nadler, S.A.; Paggi, L.; Barros, N.B.; D’Amelio, S. Molecular characterization and phylogeny of anisakid nematodes from cetaceans from southeastern Atlantic coasts of USA, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 108, 781–792.

- Perkins, S.L.; Martinsen, E.S.; Falk, B.G. Do molecules matter more than morphology? Promises and pitfalls in parasites. J. Parasitol. 2011, 138, 1664–1674.

- D’Amelio, S.; Lombardo, F.; Pizzarelli, A.; Bellini, I.; Cavallero, S. Advances in Omic Studies Drive Discoveries in the Biology of Anisakid Nematodes. Genes 2020, 15, 801.

- Mattiucci, S.; Nascetti, G. Advances and trends in the molecular systematics of anisakid nematodes, with implications for their evolutionary ecology and host-parasite co-evolutionary processes. Adv. Parasitol. 2008, 66, 47–148.

- Ondrejicka, D.A.; Locke, S.A.; Morey, K.; Borisenko, A.V.; Hanner, R.H. Status and prospects of DNA barcoding in medically important parasites and vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2014, 30, 582–591.

- Shamsi, S.; Briand, M.J.; Jean-Lou, J. Occurrence of Anisakis (Nematoda: Anisakidae) larvae in unusual hosts in Southern hemisphere. Parasitol. Int. 2017, 66, 837–840.

- Shamsi, S.; Spröhnle-Barrera, C.; Hossen, M.D.F. Occurrence of Anisakis spp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in a pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps (Cetacea: Kogiidae) in Australian waters. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2019, 134, 65–74.

- Shamsi, S.; Chen, Y.; Poupa, A.; Ghadam, M.; Justine, J.-L. Occurrence of anisakid parasites in marine fishes and whales off New Caledonia. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 3195–3204.

- Mattiucci, S.; Abaunza, P.; Damiano, S.; Garcia, A.; Santos, M.N.; Nascetti, G. Distribution of Anisakis larvae, identified by genetic markers, and their use for stock characterization of demersal and pelagic fish from European waters: An update. J. Helminthol. 2007, 81, 117–127.

- Saraiva, A.; Faranda, A.; Damiano, S.; Hermida, M.; Santos, M.J.; Ventura, C.H. Six species of Anisakis (Nematoda: Anisakidae) parasites of the black scabbardfish, Aphanopus carbo from NE Atlantic waters: Genetic markers and fish biology. Parassitologia 2007, 49, 229.

- Mattiucci, S.; Paoletti, M.; Webb, S.C. Anisakis nascettii n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from beaked whales of the southern hemisphere: Morphological description, genetic relationships between congeners and ecological data. Syst. Parasitol. 2009, 74, 199–217.

- Quiazon, K.M.A. Anisakis Dujardin, 1845 infection (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Pygmy Sperm Whale Kogia breviceps Blainville, 1838 from west Pacific region off the coast of Philippine archipelago. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 3663–3668.

- Cavallero, S.; Magnabosco, C.; Civettini, M.; Boffo, L.; Mingarelli, G.; Buratti, P.; Giovanardi, O.; Fortuna, C.M.; Arcangeli, G. Survey of Anisakis sp. and Hysterothylacium sp. in sardines and anchovies from the North Adriatic Sea. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 200, 18–21.

- Quiazon, K.M.; Yoshinaga, T.; Ogawa, K. Distribution of Anisakis species larvae from fishes of the Japanese waters. Parasitol. Int. 2011, 60, 223–226.

- Chen, H.X.; Zhang, L.P.; Gibson, D.I.; Lü, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.T.; Ju, H.D.; Li, L. Detection of ascaridoid nematode parasites in the important marine food-fish Conger myriaster (Brevoort) (Anguilliformes: Congridae) from the Zhoushan Fishery, China. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 274.

- Cho, J.; Lim, H.; Jung, B.K.; Shin, E.H.; Chai, J.Y. Anisakis pegreffii Larvae in Sea Eels (Astroconger myriaster) from the South Sea, Republic of Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2015, 53, 349–353.

- Li, L.; Zhao, J.Y.; Chen, H.X.; Ju, H.-D.; An, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.P. Survey for the presence of ascaridoid larvae in the cinnamon flounder Pseudorhombus cinnamoneus (Temminck & Schlegel) (Pleuronectiformes: Paralichthyidae). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 108–116.

- Cammilleri, G.; Pulvirenti, A.; Costa, A.; Graci, S.; Collura, R.; Buscemi, M.D.; Sciortino, S.; Vitale, B.V.; Vazzana, M.; Brunone, M.; et al. Seasonal trend of Anisakidae infestation in South Mediterranean bluefish. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 34, 158–161.

- Lim, H.; Jung, B.K.; Cho, J.; Yooyen, T.; Shin, E.H.; Chai, J.Y. Molecular diagnosis of cause of anisakiasis in humans, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 342–344.

- Gaglio, G.; Battaglia, P.; Costa, A.; Cavallaro, M.; Cammilleri, G.; Graci, S.; Buscemi, M.D.; Ferrantelli, V.; Andaloro, F.; Marino, F. Anisakis spp. larvae in three mesopelagic and bathypelagic fish species of the central Mediterranean Sea. Parasitol. Int. 2018, 67, 23–28.

- Kong, Q.; Fan, L.; Zhang, J.; Akao, N.; Dong, K.; Lou, D.; Ding, J.; Tong, Q.; Zheng, B.; Chen, R.; et al. Molecular identification of Anisakis and Hysterothylacium larvae in marine fishes from the East China Sea and the Pacific coast of central Japan. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 199, 1–7.

- Abattouy, N.; López, A.V.; Maldonado, J.L.; Benajiba, M.H.; Martín-Sánchez, J. Epidemiology and molecular identification of Anisakis pegreffii (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in the horse mackerel Trachurus from northern Morocco. J. Helminthol. 2014, 88, 257–263.

- Umehara, A.; Kawakami, Y.; Ooi, H.K.; Uchida, A.; Ohmae, H.; Sugiyama, H. Molecular identification of Anisakis type I larvae isolated from hairtail fish off the coasts of Taiwan and Japan. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 143, 161–165.

- Pawlak, J.; Nadolna-Ałtyn, K.; Szostakowska, B.; Pachur, M.; Bańkowska, A.; Podolska, M. First evidence of the presence of Anisakis simplex in Crangon and Contracaecum osculatum in Gammarus sp. by in situ examination of the stomach contents of cod (Gadus morhua) from the southern Baltic Sea. Parasitology 2019, 146, 1699–1706.

- Fonseca, M.C.; Knoff, M.; Felizardo, N.N.; Di Azevedo, M.I.; Torres, E.J.; Gomes, D.C.; Iñiguez, A.M.; Clemente, S.C.S. Integrative taxonomy of Anisakidae and Raphidascarididae (Nematoda) in Paralichthys patagonicus and Xystreurys rasile (Pisces: Teleostei) from Brazil. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 235, 113–124.

- Palm, H.W.; Theisen, S.; Damriyasa, I.M.; Kusmintarsih, E.S.; Oka, I.B.; Setyowati, E.A.; Suratma, N.A.; Wibowo, S.; Kleinertz, S. Anisakis (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea) from Indonesia. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2017, 123, 141–157.

- Shamsi, S.; Poupa, A.; Justine, J.-L. Characterisation of Ascaridoid larvae from marine fish off New Caledonia, with description of new Hysterothylacium larval types XIII and XIV. Parasitol. Int. 2015, 64, 397–404.

- Pontes, T.; D’Amelio, S.; Costa, G.; Paggi, L. Molecular characterization of larval anisakid nematodes from marine fishes of Madeira by a PCR-based approach, with evidence for a new species. J. Parasitol. 2005, 91, 1430–1434.

- Garbin, L.; Mattiucci, S.; Paoletti, M.; González-Acuña, D.; Nascetti, G. Genetic and morphological evidences for the existence of a new species of Contracaecum (Nematoda: Anisakidae) parasite of Phalacrocorax brasilianus (Gmelin) from Chile and its genetic relationships with congeners from fish-eating birds. J. Parasitol. 2011, 97, 476–492.

- Shamsi, S.; Turner, A.; Wassens, S. Description and genetic characterization of a new Contracaecum larval type (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from Australia. J. Helminthol. 2018, 92, 216–222.

- Hossen, M.S.; Shamsi, S. Zoonotic nematode parasites infecting selected edible fish in New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 308, 108306.

- Zuo, S.; Kania, P.W.; Mehrdana, F.; Marana, M.H.; Buchmann, K. Contracaecum osculatum and other anisakid nematodes in grey seals and cod in the Baltic Sea: Molecular and ecological links. J. Helminthol. 2018, 92, 81–89.

- Horbowy, J.; Podolska, M.; Nadolna-Ałtyn, K. Increasing occurrence of anisakid nematodes in the liver of cod (Gadus morhua) from the Baltic Sea: Does infection affect the condition and mortality of fish? Fish. Res. 2016, 179, 98–103.

- Pekmezci, G.Z.; Yardimci, B. On the occurrence and molecular identification of Contracaecum larvae (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Mugil cephalus from Turkish waters. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1393–1402.

- Mattiucci, S.; Sbaraglia, G.L.; Palomba, M.; Filippi, S.; Paoletti, M.; Cipriani, P.; Nascetti, G. Genetic identification and insights into the ecology of Contracaecum rudolphii A and C. rudolphii B (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from cormorants and fish of aquatic ecosystems of Central Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 1243–1257.

- Shamsi, S.; Norman, R.; Gasser, R.; Beveridge, I. Genetic and morphological evidences for the existence of sibling species within Contracaecum rudolphii (Hartwich, 1964) (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Australia. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 105, 529–538.

- Shamsi, S.; Gasser, R.; Beveridge, I.; Shabani, A.A. Contracaecum pyripapillatum n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) and a description of C. multipapillatum (von Drasche, 1882) from the Australian pelican, Pelecanus conspicillatus. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 103, 1031–1039.

- Zhao, W.T.; Xu, Z.; Li, L. Morphological variability and molecular characterization of Mawsonascaris australis (Johnston & Mawson, 1943) (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea: Acanthocheilidae) from the brown guitarfish Rhinobatos schlegelii Muller & Henle (Rhinopristiformes: Rhinobatidae). J. Helminthol. 2018, 92, 760–764.

- Shamsi, S.; Dang, M.; Zhu, X.; Nowak, B. Genetic and morphological characterization of Mawsonascaris vulvolacinata n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) and associated histopathology in a wild caught cowtail stingray, Pastinachus ater. J. Fish. Dis. 2019, 42, 1047–1056.

- Mafra, C.; Mantovani, C.; Borges, J.N.; Barcelos, R.M.; Santos, C.P. Morphological and molecular diagnosis of Pseudoterranova decipiens (sensu stricto) (Anisakidae) in imported cod sold in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2015, 24, 209–215.

- Quraishy, S.A.; Abdel-Gaber, R.; Dkhil, M.A.M. First record of Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda, Anisakidae) infecting the red spot emperor Lethrinus lentjan in the Red Sea. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019, 28, 625–631.

- Podolska, M.; Pawlikowski, B.; Nadolna-Ałtyn, K.; Pawlak, J.; Komar-Szymczak, K.; Szostakowska, B. How effective is freezing at killing Anisakis simplex, Pseudoterranova krabbei, and P. decipiens larvae? An experimental evaluation of time–temperature conditions. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 2139–2147.

- Marcer, F.; Tosi, F.; Franzo, G.; Vetri, A.; Ravagnan, S.; Santoro, M.; Marchiori, E. Updates on Ecology and Life Cycle of Sulcascaris sulcata (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Mediterranean Grounds: Molecular Identification of Larvae Infecting Edible Scallops. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 64.

- Nadler, S.A.; D’Amelio, S.; Dailey, M.D.; Paggi, L.; Siu, S.; Sakanari, J.A. Molecular phylogenetics and diagnosis of Anisakis, Pseudoterranova, and Contracaecum from northern Pacific marine mammals. J. Parasitol. 2005, 91, 1413–1429.

- Shamsi, S.; Barton, D.P.; Zhu, X. Description and characterisation of Terranova pectinolabiata n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in great hammerhead shark, Sphyrna mokarran (Rüppell, 1837), in Australia. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 2159–2168.

- Santoro, M.; Marchiori, E.; Palomba, M.; Degli, U.B.; Marcer, F.; Mattiucci, S. The Mediterranean Mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) as Intermediate Host for the Anisakid Sulcascaris sulcata (Nematoda), a Pathogen Parasite of the Mediterranean Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta). Pathogens 2020, 9, 118.

- Murata, Y.; Ando, K.; Usui, M.; Sugiyama, H.; Hayashi, A.; Tanemura, A.; Kato, H.; Kuriyama, N.; Kishiwada, M.; Mizuno, S.; et al. A case of hepatic anisakiasis caused by Pseudoterranova decipiens mimicking metastatic liver cancer. BMC Infec. Dis. 2018, 18, 619.

- Yokogawa, M.; Yoshimura, H. Clinicopathologic studies on larval anisakiasis in Japan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1967, 16, 723–728.

- Jiménez, P.N.C. Hábitos alimentarios and relación interespecífica entre la ballena azul (Balaenoptera musculus) and la ballena de aleta (B. physalus) en el suroeste del Golfo de California. Master’s Thesis, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, La paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2010.

- Arizono, N.; Yamada, M.; Tegoshi, T.; Yoshikawa, M. Anisakis simplex sensu stricto and Anisakis pegreffii: Biological characteristics and pathogenetic potential in human anisakiasis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012, 9, 517–521.

- Valiñas, B.; Lorenzo, S.; Eiras, A.; Figueiras, A.; Sanmartín, M.L.; Ubeira, F.M. Prevalence of and risk factors for IgE sensitization to Anisakis simplex in a Spanish population. Allergy 2001, 56, 667–671.

- Rezapour, M.; Agarwal, N. You Are What You Eat: A Case of Nematode-Induced Eosinophilic Esophagitis. ACG Case Rep. J. 2017, 4, e13.

- Amir, A.; Ngui, R.; Ismail, W.H.; Wong, K.T.; Ong, J.S.; Lim, Y.A.; Lau, Y.L.; Mahmud, R. Anisakiasis Causing Acute Dysentery in Malaysia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 95, 410–412.

- Shimamura, Y.; Muwanwella, N.; Chandran, S.; Kandel, G.; Marcon, N. Common symptoms from an uncommon infection: Gastrointestinal anisakiasis. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 1–7.

- Mizumura, N.; Okumura, S.; Tsuchihashi, H.; Ogawa, M.; Kawasaki, M. A Second Attack of Anisakis: Intestinal Anisakiasis Following Gastric Anisakiasis. ACG Case Rep. J. 2018, 5, e65.

- Hochberg, N.S.; Hamer, H.D. Anisakidosis: Perils of the deep. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 806–812.

- Audicana, M.T.; Fernández, C.L.; Muñoz, D.; Fernández, E.; Navarro, J.A.; Del Pozo, M.D. Recurrent anaphylaxis caused by Anisakis simplex parasitizing fish. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1995, 96, 558–560.

- Menéndez, P.; Pardo, R.; Delgado, M.; León, C. Mesenteric tumor due to chronic anisakiasis. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2005, 107, 570–572.

- Kuhn, T.; Cunze, S.; Kochmann, J.; Klimpel, S. Environmental variables and definitive host distribution: A habitat suitability modelling for endohelminth parasites in the marine realm. Sci. Rep. 2016, 10, 30246.

- Shamsi, S. Seafood-Borne Parasitic Diseases: A “One-Health” Approach Is Needed. Fishes 2019, 4, 9.

- Højgaard, D.P. Impact of temperature, salinity and light on hatching of eggs of Anisakis simplex (Nematoda, Anisakidae), isolated by a new method, and some remarks on survival of larvae. Sarsia 1998, 83, 21–28.

- Palm, H.W. Fish Parasites as Biological Indicators in a Changing World: Can We Monitor Environmental Impact and Climate Change? In Progress in Parasitology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 223–250.

- Rodríguez, H.; Bañón, R.; Ramilo, A. The hidden companion of non-native fishes in north-east Atlantic waters. J. Fish. Dis. 2019, 42, 1013–1021.

- Boussellaa, W.; Neifar, L.; Goedknegt, M.A.; Thielges, D.W. Lessepsian migration and parasitism: Richness, prevalence and inten-sity of parasites in the invasive fish Sphyraena chrysotaenia compared to its native congener Sphyraena sphyraena in Tunisian coastal waters. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5558.

- Shamsi, S.; Sheorey, H. Seafood-borne parasitic diseases in Australia: Are they rare or underdiagnosed? Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 591–596.

- Fukui, S.; Matsuo, T.; Mori, N. Palatine Tonsillar Infection by Pseudoterranova azarasi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.

2020, 103, 8. - Arizono, N.; Miura, T.; Yamada, M.; Tegoshi, T.; Onishi, K. Human infection with Pseudoterranova azarasi

roundworm. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 555–556. - Menghi, C.I.; Gatta, C.L.; Arias, L.E.; Santoni, G.; Nicola, F.; Smayevsky, J.; Degese,M.; Krivokapich, S.J. Human

infectionwith Pseudoterranova cattani by ingestion of “ceviche” in BuenosAires,Argentina. Rev. Argent. Microbiol.

2020, 52, 118–120. - Brunet, J.; Pesson, B.; Royant, M.; Lemoine, J.P.; Pfa , A.W.; Abou-Bacar, A.; Yera, H.; Fréalle, E.;

Dupouy-Camet, J.; Merino-Espinosa, G.; et al. Molecular diagnosis of Pseudoterranova decipiens s.s in human,

France. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 397. - Audicana, M.T.; Kennedy, M.W. Anisakis simplex: From Obscure Infectious Worm to Inducer of Immune

Hypersensitivity. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 360–379. - Couture, C.; Measures, L.; Gagnon, J.; Desbiens, C. Human intestinal anisakiosis due to consumption of raw

salmon. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2003, 27, 1167–1172. - Del Pozo,M.D.; Audicana,M.; Diez, J.M.;Muñoz, D.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Fernández, E.; García,M.; Etxenagusia,M.;

Moneo, I.; Fernández, C.L. Anisakis simplex, a relevant etiologic factor in acute urticaria. Allergy 1997, 52, 576–579. - Nieuwenhuizen, N.E.; Lopata, A.L. Allergic reactions to Anisakis found in fish. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep.

2014, 14, 455. - Zuloaga, J.; Arias, J.; Balibrea, J.L. Anisakiasis digestiva. Aspectos de interés para el cirujano. Cir. Esp. 2004,

75, 9–13. - Peláez, M.A.; Codoceo, C.M.; Montiel, P.M.; Gómez, F.S.; Castellano, G.; Herruzo, J.A.S. Anisakiasis múltiple.

Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2008, 100, 581–582. - Zullo, A.; Hassan, C.; Scaccianoce, G.; Lorenzetti, R.; Campo, S.M.; Morini, S. Gastric anisakiasis: Do not

forget theclinical history! J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2010, 19, 359. - Baron, L.; Branca, G.; Trombetta, C.; Punzo, E.; Quarto, F.; Speciale, G.; Barresi, V. Intestinal anisakidosis:

Histopathological findings and di erential diagnosis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2014, 210, 746–750. - Moneo, I.; Caballero, M.L.; Gómez, F.; Ortega, E.; Alonso, M.J. Isolation and characterization of a major allergen

from the fish parasite Anisakis simplex. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 106, 177–182. - Rodríguez, E.; Anadón, A.M.; García–Bodas, E.; Romarís, F.; Iglesias, R.; Gárate, T.; Ubeira, F.M. Novel

sequences and epitopes of diagnostic value derived from the Anisakis simplex Ani s 7 major allergen. Allergy

2008, 63, 219–225. - Nieuwenhuizen, N.E. Anisakis—Immunology of a foodborne parasitosis. Parasite Immunol. 2016, 38, 548–557.

- Eguia, A.; Aguirre, J.M.; Echevarria, M.A.; Martinez-Conde, R.; Pontón, J. Gingivostomatitis after eating fish

parasitized by Anisakis simplex: A case report. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2003,

96, 437–440. - Daschner, A.; Alonso, G.; Cabanas, R.; Suárez-de-Parga, J.M.; López-Serrano, M.C. Gastroallergic anisakiasis:

Border line between food allergy and parasitic disease–clinical and allergologic evaluation of 20 patients

with confirmed acute parasitism by Anisakis simplex. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 105, 176–181. - Morsy, K.; Mahmoud, B.A.; Abdel-Gha ar, F.; Deeb, E.L.S.; Ebead, S. Pathogenic Potential of Fresh, Frozen,

and Thermally Treated Anisakis spp. Type II (L3) (Nematoda: Anisakidae) after oral Inoculation in to Wistar

Rats: A Histopathological Study. J. Nematol. 2017, 49, 427–436. - Ludovisi, A.; Di-Felice, G.; Carballeda-Sangiao, N.; Barletta, B.; Butteroni, C.; Corinti, S.; Marucci, G.;

González-Muñoz, M.; Pozio, E.; Gómez-Morales, M.A. Allergenic activity of Pseudoterranova decipiens

(Nematoda: Anisakidae) in BALB/c mice. Parasite Vectors 2017, 10, 290. - Baeza, M.L.; Conejero, L.; Higaki, Y.; Martín, E.; Pérez, C.; Infante, S.; Rubio, M.; Zubeldia, J.M. Anisakis

simplex allergy: A murine model of anaphylaxis induced by parasitic proteins displays a mixed Th1/Th2

pattern. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2005, 142, 433–440. - Sakanari, J.A. Anisakis—From the platter to the microfuge. Parasitol. Today 1990, 6, 323–327.

- Shweiki, E.; Rittenhouse, D.W.; Ochoa, J.E.; Punja, V.P.; Zubair,M.H.; Baliff, J.P. Acute small-bowel obstruction

from intestinal anisakiasis after the ingestion of raw clams; documenting a new method of marine-to-human

parasitic transmission. In Open Forum Infectious Diseases; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; Volume 1. - Roser,D.; Stensvold,C.R.AnisakiasisMistaken forDientamoebiasis? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1500.

- Takei, H.; Powell, S.D. Intestinal anisakidosis (anisakidosis). Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2007, 11, 350–352.