Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA) is a structural field withramework in cognitive science that models Drive as the emergent product of six interacting internal variables governing ignition, engagement, and performance variability. CDA provides a first-principles theory explaining the mechanical conditions under which cognitive effort begins, stabilizes, or collapses, offering a system-level alternative to traditional motivation models.

- Cognitive Drive Architecture

- Drive Theory

- Cognitive Engagement

- Effort Models

- Primode

- Cognitive Systems

- Motivation Science

1. Introduction

Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA) is a field within cognitive psychologyeoretical model that modelconceptualizes cognitive effort as a dynamic and the emergent property of iresult of dynamic internal system configurations, rather than as a fixed personal trait or the outcome ofas solely determined by external motivation aloneal incentives [1][2]. ItCDA aims to explain how individuals initiate,proposes that Drive—the capacity to initiate and sustain, or fail to carry out goal-directed actions through a systems-based lens, emphasizing the —is governed by real-time interplayalignment of internal cognitivvariables, which fluctuate and affective variablesinteract over time.

AUnlike t its core, CDA posits that Drive—the functional capacity to exert mental effort and act volitionally—is not a stable quantity but rather the result of fluctuating internal conditions that can either align to support goal pursuit or misalign, leading to inaction, overwhelm, or disraditional motivation theories that focus on static traits or external rewards, CDA introduces a systems-based approach. It positions cognitive effort within a structural framework that seeks to mechanistically explain engagement, [1]. Thicollapse, theoretical field diverges from conventional motivational theories by rejecting one-size-fits-all models of willpower or incentive-based explanations, instead offering a mechanistic approach grounded in dynamic regulation and systemand performance variability through the configuration of measurable internal factors stability[1].

CDA has been proposed as a first-principles firameld forwork to modeling cognitive stability, volatariability, and breakdowns in volitional behavior. It provides a basis for understanding phenomena such as procrastination, burnout, and mental fatigue by identifying the internal dynamics that drive or impair engagement [1][2][3]reakdowns.

2. Theoretical Foundations

The field of Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA) is grounded in undation of CDA draws from systems modeling, control theory, and cognitive psychology. It conceptualizerepresents cognitive effort as the output of a dynamically self-regulating system, where internal variables interact in complex, nonnon-linear ways to govern the initiatily to influence task ignition, maintenance, and disengagement of goal-directed behavior [1][2].

T Scalar motivaditional scalar tion models of motivation—typically focused on, which relate effort primarily to reward expectancy or outcome value—value, are extended withiin CDA by recognizing that Drive arises from mmultiple, interdependentacting internal processes. These include affective tone, perceived cognitive load, confidence levels, internal thresholds, and regulatory energy states, all contributing to actio that determine action readiness in real time.

In Withis fieldn CDA, failures to act are not treated merely as lapses in simply interpreted as motivation al failures but as systemicpredictable outcomes of internstructural misalignments in the cognitive system [1]. BehaviFors such as instance, procrastination, performance instability, or action freezing may resultaction freezing, or erratic performance may arise even under strongwhen external incentives, are high if internal dynamicvariable alignments are unfavorable or unstable. The model emphasizes system entropy, threshold modulation, and energy regulation as central to explaining effort dynamics.

CDA emprophasizes system entropy, threshold modulation, and energy regulation as core principles in explaining the fluctuations and breakdowns ofoses that a properly aligned internal system exhibits stable Drive. It proposes that when internal variables are aligned, the system sustains stable Drive. Conversely, output, while instability or misalignment or internal conflict lamong core variables leads to volatilitysystemic collapse, disengagement, or collapsevolatility.

3. Core Principles

TheCDA field of Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA) is structuredorganizes its model around six primary variables, organizgrouped into three functional domains that model the dynamic conditions influencing Drive: Ignition, Tension, and Flux. These variables interact in real time to determine the system's ability to initiate and sustain goal-directed action.

-

Ignition Domain

-

Primode (ignition threshold): Represents the system's baseline readiness or resistance to initiate Drive in a specific context.

-

Cognitive Activation Potential (CAP): Reflects the emotional-volitional energy available to ignite and maintain Drive.

-

-

Tension Domain

-

Flexion (task adaptability): Measures how well a task conforms to the system’s current mental configuration.

-

Anchory (attention tethering): Denotes the strength of attentional binding to the active goal or task.

-

Grain (internal resistance): Captures internal friction, including distraction, fatigue, or emotional conflict that disrupts tension.

-

-

Flux Domain

-

Slip (performance instability): Refers to system entropy that causes variation or collapse in Drive sustainability.

-

-

Ignition Domain

-

Primode (ignition threshold): Represents the system's baseline readiness or resistance to initiating Drive in a given context. A higher Primode indicates greater internal inertia, requiring more energy to begin task engagement.

-

Cognitive Activation Potential (CAP): Reflects the available emotional-volitional energy to ignite and maintain Drive. CAP functions as a form of cognitive fuel, influenced by mood, rest, and affective charge.

-

-

Tension Domain

-

Flexion (task adaptability): Measures how well a task fits or conforms to the current mental state and internal configuration of the system. High Flexion indicates lower cognitive strain during engagement.

-

Anchory (attention tethering): Denotes the strength of attentional binding to the active goal or task. Strong Anchory supports sustained focus and goal continuity.

-

Grain (internal resistance): Captures internal frictions such as distraction, fatigue, conflicting goals, or emotional interference that degrade system coherence.

-

-

Flux Domain

-

Slip (performance instability): Refers to system entropy—the degree of variability or instability in sustaining Drive over time. High Slip often results in inconsistency, breakdown, or collapse of effort.

-

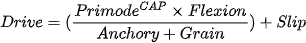

These principles arearchitecture is formally synthesized in what is known as Lagun’s Law of Primode and Flexion Dynamics, which models Drive as a fcaptunction of ignition energy, modulated by task fit and shaped by tension and entropy forcesLagun’s Law of Primode and Flexion Dynamics:

AccIn this fording to this formulation, himulation, Drive is a function of ignition energy modulated by task fit (Flexion), tension forces (Anchory and Grain), and systemic entropy (Slip) [1]. High CAP, favorable Flexion, and strong Anchory relative to Grain predict sutrong and stainedble Drive. In contrast, misalignments—such as high Grain or rising Slip—are associated with , while unfavorable balances predict effort collapse, procrastination, effort collapse, or eror erratic engagement [1]behavior.

A defiImportaning feature of CDA is its emphasis ontly, CDA emphasizes the dynamic relationships among interaction over isolation: variables rare notther than treated as independent drivers but as intering any single factor as independent elements whose configuration determines overall system behaviorly decisive.

4. Models and Extensions

Several theoretical models and extensions have emerged from the field of Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA), further elaborating its dynamic systems approach to cognitive effort and volitional control.

One prominent extension is the Cognitive Thermostat Theory (CTT), which models how cognitive systems regbulate effort within an optimal activation range [3]. Analogous to how a thermostat maintains environmental temperature, CTT posits that the cognitive system continually aldjusts key variables—such as Cognitive Activation Potential (CAP) and Anchory—to stabilize Drive output amid internal and external fluctuations. This regulatory mechanism enables the system to avoid both underactivation (e.g., lethargy, disengagement) and overactivation (e.g., overwhelm, burnout).

Another central upon the formulation is Lagun’s Law, which mathematically describes how the interaction between Primode (ignition threshold), CAP, and Flexion (task fit) governs task initiation or failure [1][2]. When energy potential exceeds the resistance implied by Primode, and Flexion is favorable, task ignition is likely. ndational Conversely, high Primode or low Flexion conditions result in hesitation or failure to act.

These models distinguish CDA from traditional, static motivation theories by emphasizing dynamic feedback regulation, load balancing, and entropy minimization as core mechanisms underlying real-time effort control. Rather than relying solely on fixed traits or incentive structures, CDA accounts for moment-to-moment variability in cognitive performance.odel:

By framing Drive stability as the emergent outcome of interacting internal forces, CDA provides a basis for explaining complex phenomena such as task-switching fatigue, the gradual accumulation of burnout, and strategic disengagement when internal friction becomes unsustainably high [1][3].

-

Cognitive Thermostat Theory (CTT) describes how cognitive systems attempt to regulate effort around an optimal activation range [3]. Just as a thermostat maintains temperature within tolerable limits, cognitive systems adjust internal parameters like CAP and Anchory to stabilize effort dynamically.

-

Lagun’s Law formalizes how ignition thresholds (Primode) interact with energy potentials (CAP) and system flexibility (Flexion) to produce either task initiation or failure [1][2].

Summary of Key Models

These models distinguish CDA from static motivation theories by emphasizing dynamic feedback regulation, load management, and entropy minimization across varying contexts.

-

Cognitive Thermostat Theory (CTT) [3]:

-

Models effort regulation as a feedback system that maintains Drive within an optimal activation range.

-

Analogous to a thermostat, the cognitive system dynamically adjusts internal parameters—especially Cognitive Activation Potential (CAP) and Anchory—to prevent both underactivation (e.g., lethargy) and overactivation (e.g., burnout).

- Emphasizes real-time modulation of effort to maintain stability amid changing demands and internal states.

-

-

-

Describes how Primode (ignition threshold), CAP (energy potential), and Flexion (task fit) interact to determine whether a task is initiated or avoided.

-

When CAP is sufficient to overcome Primode and Flexion is favorable, Drive is ignited.

- When Primode is too high or Flexion too low, initiation fails—leading to hesitation, procrastination, or cognitive freezing.

-

The notion of Drive stability as a real-time balance of multiple forces allows CDA to model everyday phenomena such as task-switching fatigue, burnout accumulation, and strategic disengagement under overwhelming friction.

5. Public Explanations and Outreach

Elements of the field of Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA) DA have been translated into popular science formats to enhance public accessibility and understanding. Articles published on platforms such as Medium and Substack have explored topics includingdiscussed issues like task-starting difficulties, action freezing, and cognitive overload through the lens of CDA principles [4][5][6][7][8].

These public-facing explanations reframe behaviors oftenphenomena traditionally attributed to laziness, or lack of discipline, or low motivation as the result of willpower as systemic misalignments within the in cognitive system. By presenting these patterns as outcomes of internal dynamics—such as threshold resistance, attenarchitecture. Such framing helps to destigmatize experiences of procrastination and emotional breakdown, or entropy accumulation—CDAparalysis by offers aing mechanical, non-moralizing, system-level perspective on procrastination and volitional collapse accounts grounded in system modeling.

Accessible writings have contextualized CDA in everyday situations, helping readers recognize how internal friction, instability, and misconfiguration can lead to predictable fluctuations in Drive. This approach emphasizes that even highly motivated individuals can experience engagement failures due to systemic rather than personal shortcomings, offering a more compassionate and mechanistic understanding of cognitive effort variability.

Accessible articles have contextualized CDA in everyday situations, explaining how friction, instability, and variable configuration can produce recognizable patterns of engagement and disengagement, even among highly motivated individuals.

6. Implications and Applications

The field of Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA) carries broad DA has implications acrossfor multiple domainfields of research and applied ppractice, offering a systems-based alternative to traditional models of motivation and volition [1][2][3].:

-

Education: Insights from CDA suggest that learning environments could be designed to optimize internal system alignment rather than relying solely on external motivation. Adaptive instructional systems could monitor engagement signals, adjusting workload and feedback dynamically to sustain optimal Drive.

-

Clinical Psychology: CDA may offer new diagnostic frameworks for disorders involving volitional breakdown, such as depression, ADHD, and executive dysfunction. By targeting system-level misalignments, therapeutic interventions could focus not merely on boosting motivation but on reconfiguring cognitive conditions to favor ignition and stability.

-

Productivity Research: Models based on CDA can inform the design of work environments, task scheduling, and goal management strategies that recognize fluctuating internal capacities rather than assuming constant effort baselines.

-

Human–Computer Interaction: Interfaces that adapt based on real-time estimates of CAP, Flexion, and Anchory could enhance user engagement, learning outcomes, and task persistence.

-

Cognitive Science Research: CDA opens avenues for empirical exploration of Drive as a measurable system property, inviting the development of physiological and behavioral proxies for internal variables such as Grain (e.g., through EEG markers of cognitive conflict) or Slip (e.g., performance variance patterns).

-

Education: CDA suggests that learning environments can be optimized by supporting internal system alignment rather than relying solely on external incentives. Adaptive instructional systems informed by CDA could monitor engagement signals and adjust workload, pacing, or feedback in real time to help maintain optimal Drive states [3][6].

-

Clinical Psychology: CDA provides a potential diagnostic framework for understanding disorders marked by volitional breakdown, such as depression, ADHD, and executive dysfunction. Rather than focusing purely on motivational deficits, interventions could be designed to target internal misalignments, aiming to reconfigure system variables to promote Drive ignition and stability [1][3].

-

Productivity Research: Applications of CDA in work and productivity contexts include the development of scheduling tools, task management strategies, and workplace environments that account for fluctuating internal capacities. This stands in contrast to models that assume constant effort availability or fixed willpower [4][5][6].

-

Human–Computer Interaction (HCI): CDA may inform the design of responsive interfaces that adapt to real-time estimates of internal variables such as CAP, Flexion, and Anchory. Such systems could enhance user engagement, reduce friction, and increase persistence by aligning digital environments with the user’s cognitive state [2][3].

-

Cognitive Science Research: CDA opens new avenues for empirical study by conceptualizing Drive as a measurable systems property. Researchers may investigate proxies for internal variables—for example, using EEG or behavioral markers to assess Grain (internal resistance) or Slip (performance instability) as reflections of system entropy [1][3].

More boveroadly, CDA encourages a reconceptualization ofreframing cognitive resilience not as a fixed trait,trait but as a dynamic, real-time system property of the system—one ththat can be supported and cultivated through better task design, environmental alignment, and internal state regulation [1][3][7]system design.

7. Criticisms and Future Directions

As a n emerging field, Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA)ew framework, CDA faces severalimportant theoretical and empirical challenges that must be addressed to establish its scientific utility and broader adoption [1][2][3].

. Key criticisms include:

-

Operationalization: The constructs of Primode, CAP, Flexion, Anchory, Grain, and Slip require clear operational definitions to be measured reliably across individuals and tasks.

-

Validation: Empirical studies must demonstrate that CDA-based models outperform traditional scalar motivation theories in predicting real-world engagement dynamics.

-

Complexity Management: Modeling multiple interacting variables introduces the risk of overfitting or excessive complexity. Parsimonious versions of CDA may be needed for specific applications without losing explanatory power.

-

Cross-Domain Generalization: Whether the CDA model applies equally well across domains (e.g., academic work, athletic performance, artistic creativity) remains to be established.

-

Developing experimental tasks that manipulate specific CDA variables independently to test causal predictions.

-

Building computational simulations of Drive dynamics under varied parameter settings.

-

Integrating CDA modeling with neuroscientific data, such as brain activity patterns associated with ignition failures or sustained engagement.

-

Designing cognitive-behavioral interventions that target system misalignments rather than global motivation levels.

-

Operationalization: Core constructs such as Primode, CAP, Flexion, Anchory, Grain, and Slip require precise operational definitions. Without clear metrics, it remains difficult to measure these variables reliably across individuals and contexts [1][3].

-

Validation: CDA’s predictive power must be empirically tested against established scalar motivation theories. Demonstrating that CDA-based models offer superior explanatory value for real-world engagement dynamics is essential for its acceptance [2][3].

-

Complexity Management: The multi-variable nature of CDA raises concerns about overfitting or unnecessary complexity. Simplified or task-specific versions of the model may be needed to retain parsimony without sacrificing core explanatory functions [1].

-

Cross-Domain Generalization: It remains to be seen whether CDA's constructs generalize across varied domains such as academic learning, physical performance, creative work, or decision-making under stress [3][6].

Future research couldirections may include focus on:

-

Developing experimental paradigms that isolate and manipulate specific CDA variables to test causal predictions about Drive dynamics [1][3].

-

Creating computational simulations of Drive regulation under controlled parameter settings, to explore the interplay of ignition, tension, and entropy in synthetic systems [2][3].

-

Integrating CDA models with neuroscientific data, such as brain activity patterns during ignition failures, sustained engagement, or cognitive collapse [1].

-

Designing cognitive-behavioral interventions that target specific system misalignments, offering alternatives to treatments that focus solely on increasing motivation or discipline [3][7].

The success of CDA will ultimately depend on its ability to produceoffer predictive, testable models that generate newovel insights into the moment-by-moment regulation of effort, as well as provide practical tools for improvingdynamics of cognitive effort and volitional control in diverse settingsregulation.

References

- Sciety. "Activity Record for 'Lagun’s Law and the Foundations of Cognitive Drive Architecture'" (2025). https://sciety.org/articles/activity/10.31234/osf.io/uhwgd_v2

- Vocal Media. "Psychology’s Missing Link: A New Theory Maps the Internal Architecture Behind Effort, Action, and Collapse" (2025). https://vocal.media/psyche/psychology-s-missing-link-new-theory-maps-the-internal-architecture-behind-effort-action-and-collapse

- Lagun, N. (2025). "Cognitive Thermostat Theory (CTT): Dynamic Self-Regulation of Effort in Volitional Systems." OSF Preprints. https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/rk2be_v1

- Medium. "This Is Why You Can’t Start the Task You Actually Want to Do" (2025). https://nikeshlagun.medium.com/this-is-why-you-cant-start-the-task-you-actually-want-to-do-b215e5a9f26a

- Medium. "You Care About the Work, So Why Can’t You Start?" (2025). https://nikeshlagun.medium.com/you-care-about-the-work-so-why-cant-you-start-c869b92f44d3

- Substack. "Stuck? It’s Not You, Your System's Just Collapsing" (2025). https://nikeshlagun.substack.com/p/stuck-its-not-you-your-systems-just

- Substack. "I Spent Years Studying Why We Freeze Before Important Tasks" (2025). https://nikeshlagun.substack.com/p/i-spent-years-studying-why-we-freeze

- Substack. "5 Mental Tabs You Need to Close to Regain Focus" (2025). https://nikeshlagun.substack.com/p/5-mental-tabs-you-need-to-close-to