Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Arao Fu and Version 1 by Seedhabadee (Pooba) Ganeshan.

Sustainable solutions to the use of petrochemical products have been increasingly sought after in recent years. While alternatives such as biofuels have been extensively explored and commercialized, major challenges remain in using heterogeneous feedstocks and scaling-up processes. Among biofuels, higher alcohols have recently gained renewed interest, especially in the context of upcycling agri-food residues and other industrial organic wastes. One of the higher alcohols produced via fermentation is butanol, which was developed over a century ago. However, the commercial production of butanol is still not widespread, although diverse feedstocks are readily available. Hydrolysis of the feedstocks and scale-up challenges in the fermentation and purification of butanol are recurring bottlenecks. This review addresses the current state of fermentative butanol production and opportunities to address scale-up challenges, including purification. With the significant interest and promise of precision fermentation, this review also addresses some of the recent advances and potential for enhanced fermentative butanol production.

- butanol

- feedstocks

- precision fermentation

- scale-up

Our dependence on fossil fuels is immeasurable, and despite our best efforts to become less dependent, the availability of alternatives is still yet to supplant existing petrochemical-derived products. The staggering increase in primary energy consumption over many decades reinforces our astounding dependence on fossil fuels (Figure 1), which was only made more significant with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution [1,2,3][1][2][3]. Interestingly, in 2019, there was a decrease in primary energy consumption due to the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, which led to a global lockdown and a reduction in industrial activity and, indeed, human commute in general. However, the pandemic has also offered a glimpse into what a reduction in energy consumption might look like on the overall climate change outlook and humanity’s existence per se. One of the debatable questions was whether COVID-19 could lead to extinction, not because of the COVID-19 disease, but rather due to reduced industrial activity that could lead to temperature increases due to the lack of the dimming effects of aerosols generally associated with industrial activity protecting against such rapid increases in temperatures [4]. While this debate regarding the extinction of life is unlikely to be resolved in the near future, the increasing trend in primary energy consumption derived from fossil fuels since the dip observed in 2019 certainly calls for renewed perspectives into renewable sources of energy for environmental sustainability. Butanol, one of the most promising and widely studied alternatives, is worth revisiting in this context.

While butanol can be chemically synthesized from petrochemical fossil fuels via the hydrolysis of haloalkanes or hydration of alkenes [5], sustainable or renewable sources for energy production have been a long-standing area of focus, particularly with respect to feedstocks and thermochemical or biological approaches. Biofuels, for example, have been routinely used to produce products such as biodiesel and ethanol from feedstocks such as lignocellulosic biomass [6]. The term “biofuels” has been applied to the use of biomass for the production of fuels, be it gas, liquid, or solid, including products such as biomethanol, bioethanol, biohydrogen, biodiesel, biochar, bio-synthetic gas, etc. [7]. Since biomass is a renewable alternative, it was perceived as an ideal substrate for the production of biofuels. Subsequently, the strategy of biofuel production shifted from chemical conversions to biological conversions using microorganisms. The use of microorganisms for the production of value-derived products using biomass is not new and has been in existence for millennia. Beer, for example, has been documented to have been produced and consumed as far back as 7000 years ago in China [8]. Archaeological excavations have revealed that a clay tablet dated back to 6000 BC with likely one of the oldest beer recipes inscribed on it in Mesopotamia [9]. Similarly, the earliest chemical evidence for wine from a Neolithic village’s pottery jar was dated to have been produced around 5400–5000 BC [10]. Whether this is intentional production is still debatable. However, archaeological evidence for an intentionally fermented beverage that was not produced by the well-established Vitis vinifera or its ancestors was found and dated over 7000 BC in a Neolithic area near the Yellow River in China [11]. Since then, the use and exploitation of microorganisms for the production of other value-derived products has slowly gained prominence to the extent that any organic residue can become a source of feedstock for microbial activity.

In our current context, the selected feedstocks for the production of the various biofuels have been categorized into generations based on their chronological usage, including the production of biobutanol, which is the focus of this review. Butanol has been seen as ideal due to its higher energy content, lower volatility, lower absorption of water, easier blending with gasoline and, importantly, its compatibility with conventional combustion engines compared to ethanol [12,13][12][13] (Table 1). Besides its potential application as an alternative to fossil fuels, butanol has had applications in the chemical industry for the production of methacrylate esters, butyl acrylate, butyl glycol ether, butyl acetate, and plasticizers. Globally, over 50% of the produced butanol is converted to acrylate and methacrylate esters [12,14][12][14]. According to Market Research Future, the estimated size of the biobutanol market in 2024 was USD 1.4 billion and is expected to increase from USD 1.18 billion in 2025 to USD 3.5 billion by 2034, with an expected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 13.18% between the forecast period of 2025 to 2034 [15]. The optimism around biobutanol is due to the fact that technological advancements have allowed for reduced cost of production and higher efficiency at scale [15]. Nonetheless, there are still a limited number of industrial biobutanol manufacturing facilities globally [16]. Thus, the objective of this review is to offer some perspectives on biobutanol production, scale-up challenges, and the promise of precision fermentation. While fermentative aspects of biobutanol production have been exhaustively addressed, some of the recurring bottlenecks include inhibitory accumulation of the biobutanol, which precludes higher titers of butanol. Furthermore, many of the studies have focused on laboratory scale process optimization, which is unfortunately not amenable to scale-up. Similarly, metabolic engineering approaches to enhance biobutanol production have been conducted [17], including the use of synthetic biology [18]. Biobutanol production is also likely to receive further impetus due to extensive research efforts toward utilizing feedstocks from agri-food waste streams, which offer new perspectives into upcycling and sustainability approaches in a circular economy context. The development of engineered strains capable of more efficient acetone–butanol–ethanol (ABE) fermentation will certainly aid in the use of agri-food waste streams. However, engineered strains are not available for broader use and have not been reported to be commercially used. Therefore, general ABE fermentation is still dependent on available wild-type strains, which, as mentioned above, are prone to inhibition due to increasing concentrations of butanol during fermentation or other potential inhibitors arising from the side streams.

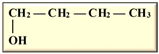

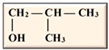

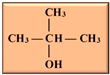

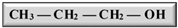

Table 1. Isomers of butanol and other alcohols, as well as some of their characteristics (sources: [19,20,21][19][20][21]).

n-Butanol n-Butanol |

sec-Butanol sec-Butanol |

iso-Butanol iso-Butanol |

tert-Butanol tert-Butanol |

Methanol Methanol |

Ethanol Ethanol |

Propanol Propanol |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boiling point (°C) | 118 | 99.5 | 108 | 83 | 64.7 | 78.1 | 97 |

| Melting point (°C) | −90 | −115 | −108 | 25.7 | −97.6 | −114.1 | −126 |

| Density (Kg/L) | 0.81 | 0.806 | 0.802 | 0.791 | 0.792 | 0.789 | 1.049 |

| Flash point (°C) | 35 | 31 | 28 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 15 |

| Motor octane number | 78 | 32 | 94 | 89 | 97–104 | 100–106 | - |

References

- Richie, H.; Rosado, P. Fossil Fuels. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/fossil-fuels (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Smil, V. Energy Transitions: Global and National Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2017.

- Energy Institute. Statistical Review of World Energy. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- McPherson, G.R. Will COVID-19 Trigger Extinction of All Life on Earth? Earth Environ. Sci. Res. Rev. 2020, 73, 73–74.

- Shapovalov, O.I.; Ashkinazi, L.A. Biobutanol: Biofuel of second generation. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2008, 81, 2232–2236.

- Mahapatra, M.; Kumar, A. A Short Review on Biobutanol, a Second Generation Biofuel Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass. J. Clean Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 27–30.

- Demirbas, M.F. Biorefineries for biofuel upgrading: A critical review. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, S151–S161.

- Bai, J.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S.; Boswell, M. Beer Battles in China: The Struggle over the World’s Largest Beer Market. In The Economics of Beer; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 267–286.

- Poelmans, E.; Swinnen, J.F.M. A Brief Economic History of Beer. Econ. Beer 2011, 3–28.

- McGovern, P.E.; Glusker, D.L.; Exner, L.J.; Voigt, M.M. Neolithic resinated wine. Nature 1996, 381, 480–481.

- McGovern, P.E.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hall, G.R.; Moreau, R.A.; Nuñez, A.; Butrym, E.D.; Richards, M.P.; Wang, C.-S.; et al. Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17593–17598.

- Dürre, P. Biobutanol: An attractive biofuel. Biotechnol. J. 2007, 2, 1525–1534.

- Rosenblatt, D.; Morgan, C.; McConnell, S.; Nuottimäki, J. Particulate Measurements: Ethanol and Isobutanol in Direct Injection Spark Ignited Engines; International Energy Agency-Advanced Motor Fuels: Paris, France, 2015.

- Dürre, P. Fermentative Butanol Production. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1125, 353–362.

- Nagrale, P. Biobutanol Market Research Report. Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/bio-butanol-market-28603 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Jain, A.; Rajagopalan, G. Biobutanol production from food crops. In Advances and Developments in Biobutanol Production; Segovia-Hernandez, J.G., Behera, S., Sanchez-Ramirez, E., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 245–260.

- Sooch, B.S.; Singh, J.; Verma, D. Insights into metabolic engineering approaches for enhanced biobutanol production. In Advances and Developments in Biobutanol Production; Segovia-Hernandez, J.G., Behera, S., Sanchez-Ramirez, E., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2023; pp. 329–361.

- Nanda, S.; Golemi-Kotra, D.; McDermott, J.C.; Dalai, A.K.; Gökalp, I.; Kozinski, J.A. Fermentative production of butanol: Perspectives on synthetic biology. New Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 210–221.

- Hongjuan, L.; Genyu, W.; Jianan, Z. The Promising Fuel-Biobutanol. In Liquid, Gaseous and Solid Biofuels; Zhen, F., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 175–198.

- AMF. Butanol. Available online: https://www.iea-amf.org/content/fuel_information/butanol/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Panahi, H.K.S.; Dehhaghi, M.; Kinder, J.E.; Ezeji, T.C. A review on green liquid fuels for the transportation sector: A prospect of microbial solutions to climate change. Biofuel Res. J. 2019, 6, 995–1024.

More