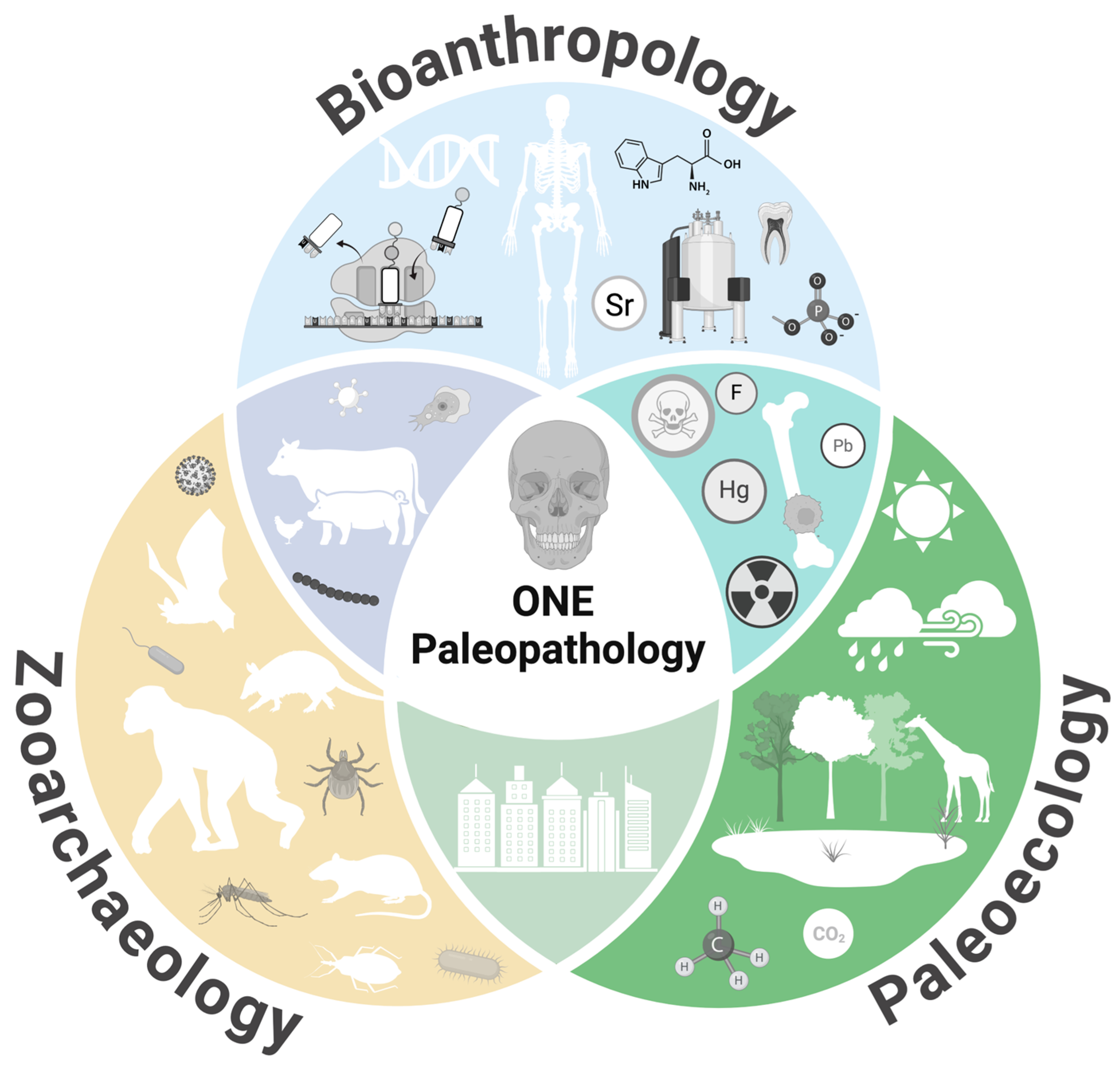

This entry explores the emergence of ONE Paleopathology as a holistic, interdisciplinary approach to understanding health through deep time. The entry discusses key areas where paleopathological research provides crucial insights: animals as sentinels of environmental health, the evolution and transmission of infectious diseases, the impacts of urbanization and pollution on human health, and the effects of climate change on disease patterns. Special attention is given to case studies involving malaria, tuberculosis, and environmental toxicity, demonstrating how past human–environment interactions inform current health strategies. The entry also emphasizes the importance of indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) systems in understanding and managing health challenges, highlighting how traditional ecological knowledge complements scientific approaches. By bridging past and present, ONE Paleopathology offers valuable perspectives for addressing modern health challenges in the context of accelerating environmental change, while promoting more equitable and sustainable approaches to global health.

- global public health

- environmental health

- well-being of humans

- animals

- ecosystems

References

- Conrad, L.I. The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; Volume 1.

- Zinsstag, J.; Schelling, E.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Tanner, M. From “ONE Medicine” to “ONE Health” and Systemic Approaches to Health and Well-Being. Prev. Vet. Med. 2011, 101, 148–156.

- Brenna, C.T. Bygone Theatres of Events: A History of Human Anatomy and Dissection. Anat. Rec. 2022, 305, 788–802.

- Ghosh, S.K. Human Cadaveric Dissection: A Historical Account from Ancient Greece to the Modern Era. Anat. Cell Biol. 2015, 48, 153–169.

- Schwabe, C.W. Veterinary Medicine and Human Health; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1984.

- Gyles, C. One Medicine, One Health, One World. Can. Vet. J. 2016, 57, 345.

- Zhou, X.; Zheng, J. Building a Transdisciplinary Science of One Health with a Global Vision. Glob. Health J. 2024, 8, 99–102.

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; De Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028.

- Bird-David, N. “Animism” Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology. Curr. Anthropol. 1999, 40, S67–S91.

- Hernandez, J. Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022.

- Kimmerer, R. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants; Milkweed Editions: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013.

- Bartosiewicz, L.; Mansouri, K. Zooarchaeology and the Paleopathological Record. In The Routledge Handbook of Paleopathology; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 557–575.

- Gluckman, P.D.; Low, F.M.; Hanson, M.A. Anthropocene-Related Disease: The Inevitable Outcome of Progressive Niche Modification? Evol. Med. Pub. Health 2020, 2020, 304–310.

- Bendrey, R.; Fournié, G. Zoonotic Brucellosis from the Long View: Can the Past Contribute to the Present? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 42, 505–506.

- Bendrey, R.; Cassidy, J.P.; Fournié, G.; Merrett, D.C.; Oakes, R.H.; Taylor, G.M. Approaching Ancient Disease from a One Health Perspective: Interdisciplinary Review for the Investigation of Zoonotic Brucellosis. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2020, 30, 99–108.

- Buikstra, J.E.; Uhl, E.W. 21st Century Paleopathology: Integrating Theoretical Models with Biomedical Advances. Asian J. Paleopathol. 2023, 5, 1–7.

- Fournié, G.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Bendrey, R. Early Animal Farming and Zoonotic Disease Dynamics: Modelling Brucellosis Transmission in Neolithic Goat Populations. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 160943.

- Littleton, J.; Karstens, S.; Busse, M.; Malone, N. Human-Animal interactions and infectious Disease: A View for Bioarchaeology. Bioarchaeol. Int. 2022, 6, 133–148.

- Mitchell, P.D. Using Paleopathology to Provide a Deep-Time Perspective that Improves our Understanding of One Health Challenges: Exploring Urbanization. Res. Dir. One Health 2024, 2, E5.

- Rayfield, K.M.; Mychajliw, A.M.; Singleton, R.R.; Sholts, S.B.; Hofman, C.A. Uncovering the Holocene Roots of Contemporary Disease-Scapes: Bringing Archaeology into One Health. Proc. R. Soc. B 2023, 290, 20230525.

- Robbins Schug, G.; Buikstra, J.E.; Dewitte, S.N.; Baker, B.J.; Berger, E.; Buzon, M.R.; Davies-Barrett, A.M.; Goldstein, L.; Grauer, A.L.; Gregoricka, L.A.; et al. Climate Change, Human Health, and Resilience in the Holocene. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, E2209472120.

- Thomas, R. Nonhuman Animal Paleopathology—Are We So Different? In Ortner’s Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 809–822.

- Uhl, E.W.; Kelderhouse, C.; Buikstra, J.; Blick, J.P.; Bolon, B.; Hogan, R.J. New World Origin of Canine Distemper: Interdisciplinary Insights. Int. J. Paleopathol. 2019, 24, 266–278.