Indonesia, which predominantly consists of maritime areas, faces complexities in implementing spatial planning. The RZWP3K (Coastal Zone and Small Islands Zoning Plan), a component of the marine spatial planning document, has not been adopted as a reference in the marine spatial plan. To address this, the government has achieved a policy breakthrough concerning spatial planning— integrating land and marine spatial planning into a singular spatial planning product. Even so, it will be hard to implement one spatial planning policy because Indonesia's regional development plans have mostly ignored the marine environment, seeing the sea as a barrier to regional development rather than an asset. Therefore, it is essential to examine the elements that will influence the successful execution of the policy in the Rebana Metropolitan Area.

- spatial planning

- planning management

- integrated spatial planning

- land-sea integrated planning

- one spatial planning policy

- Rebana Metropolitan Area

1. Introduction

Indonesia is the largest archipelago in the world, with waters covering 62.8% of its total area. Therefore, there is a need to regulate the management of marine resources in order to minimize conflicts over the use of space and also to provide legal certainty for business activities. To respond to this, the Government of Indonesia has issued two legal bases in marine regulation, namely Law No. 27 of 2007 as amended by Law No. 1 of 2014 on the Management of Territory, Coastal and Small Islands, and Law No. 32 of 2014 on Marine Affairs. Both laws require the development of RZWP3K (Coastal Zone and Small Islands Zoning Plan) and Marine Spatial Plans. In reality, however, the RZWP3K is inadequate and cannot even function as a marine spatial plan. The RZWP3K only functions as a part of the marine spatial planning document mandated by Law No. 32/2014 on Maritime Affairs.There are legal differences between the RZWP3K and the marine spatial plan. For example, the terms "coastal zone" and "sea" are defined differently in the two sets of rules. There is also a difference in what the RZWP3K regulates: it only covers coastal zones and small islands, not marine space (1)[1].

There is also a problem when the RZWP3K that was made is not combined with other spatial plans. In this case, the RTRW (Regional Spatial Plan) is not combined with the RZWP3K. This is because the RTRW is an implementation of Law No. 26 of 2007 on spatial planning. Referring to the positive law of RZWP3K, RZWP3K must be prepared integratively with RTRW. The RTRW is a planning document that controls land-based spatial planning. When land-based and sea-based spatial planning are combined, it is expected that resource management will be more harmonious, integrated, and sustainable. In reality, the RZWP3K document is not integrated with the RTRW due to the differentiation of authority (different agencies are authorized to prepare plans) and the differentiation of space allocation (1)[1]. In addition, there is also differentiation in the mechanisms of document preparation and synchronization due to the different legal sources used. On the one hand, Law No. 27 of 2007, as amended by Law No. 1 of 2014 on the management of territories, coastal areas, and small islands, says that the RZWP3K must be made at the national and provincial levels. On the other hand, Law No. 26 of 2007 on Spatial Planning says that the RTRW must be made at the national, provincial, and district/city levels.

Indonesia's spatial planning is complicated by the different ways that the RZWP3K and the RTRW are integrated with the Marine Spatial Plan and with each other. These planning products run in their respective corridors, not integrated with each other, even though Law No. 26/2007 on Spatial Planning clearly states that what is meant by space is a container that includes land space, sea space, and air space, including space within the earth as a unified region. The sea management becomes partial, separated from land management, preventing the region's development potential from being fully realized.

The Presidential Regulation No. 16 of 2017 on Indonesian Ocean Policy made combining land and marine spatial planning more important. It says that because Indonesia is an archipelagic country, combined marine spatial planning is needed to develop the area and boost economic activities. The rule also says that there needs to be a single point of reference for how marine space is used that is linked to land spatial planning. This way, different interests and needs can be met without using space incompatibly.

These are the two spatial planning products that have come out since the regulation was made: Government Regulation No. 13 of 2017 on Amendments to Government Regulation No. 26 of 2008 on National Spatial Plan (RTRWN) and Government Regulation No. 32 of 2019 on Marine Spatial Plan (RTRL). In principle, there are references for the organization of spatial planning in both land and marine areas. However, the comparison of the content between the two plans has not shown integration in the regulation of land and sea areas. Because of this issue, the government made a big step forward in spatial planning by combining land and sea planning into a single product. This was done by releasing Government Regulation No. 21 of 2021 on the Implementation of Spatial Planning, which is also known as the "one spatial planning policy." The government regulation, which is one of the implementing regulations of Law No. 11 of 2020 on Job Creation, requires that land and sea spatial planning, which have been separate, be integrated into one spatial planning document.

Through the integration of land and sea spatial planning, a balance is expected between the use and conservation of natural resources and the environment to achieve prosperity and sustainability. Why is this important? Spatial planning plays a crucial role in development, both at the national and regional levels. It acts as a link between different actors, sectors, and regions to accommodate different interests. It also controls the distribution and allocation of programs and activities to promote growth and fairness. Therefore, the integration of land and sea spatial planning must be immediately outlined in the framework of "one plan, one governance."

However, considering that Indonesia's regional development policies have tended to ignore the role of the sea, where the sea is still seen as a barrier rather than a potential in regional development, one spatial planning policy will certainly not be easy to implement. This can be seen in the development of the Rebana Metropolitan Area, which is one of the priority areas in the development and management of development problems based on Presidential Regulation No. 87 of 2021 on the Acceleration of the Development of the Rebana Region and the Southern West Java Region. As a metropolitan area focused on the development of industrial and urban areas and directly adjacent to the Java Sea, it should have normatively led to the integration of land and sea development. However, the development direction stated in the Presidential Regulation is still oriented toward land development, even though there are two large ports that are the nodes of the Tambourine Metropolitan Area, namely Cirebon Port in Cirebon Regency and Patimban Port in Subang Regency.

Using the same spatial planning policy for both land and sea planning is important because it gives everyone a way to see how marine space is used. It's also important that land planning is coordinated with sea planning so that different interests and needs can be met without any problems with how space is used. So, the goal of this study is to find out what factors affect the success of integrating land and sea planning so that the Rebana Metropolitan Area can use one spatial planning policy.

The next part of the article is an introduction that talks about the theoretical framework. The next part describes the study area and the methods used in this research. The third part talks about the factors that affect a spatial planning policy in the Metropolitan Rebana Area. The fourth part talks about the thematic discourse, and the fifth part gives the conclusions.

The amalgamation of terrestrial and maritime spatial planning is a multifaceted undertaking shaped by diverse elements, encompassing ecological, administrative, and socio-cultural aspects. Efficient management at the land-sea interface is essential for tackling the distinct difficulties arising from the interactions between terrestrial and marine ecosystems. This synthesis utilizes various studies that emphasize the essential factors influencing this integration.

A crucial element is the acknowledgment of land-sea interactions and their consequences for spatial design. According to (2)[2], the way that influences interact at the land-sea interface creates unique conservation and management problems. They suggest a spatially explicit paradigm that takes into account risks to estuary sustainability from both land and sea sources. Loiseau et al. say that current marine spatial plans often don't take into account stresses on land, which hurts the health of marine ecosystems (3)[3]. This error underscores the imperative of combining terrestrial management with marine spatial planning to improve ecological results (3)[3]. Inconsistent planning frameworks present obstacles to effective integration. Wang says that nowadays land planning ends at the shore and doesn't look at how it affects marine environments. On the other hand, (4)[4] says that marine planning is mostly about controlling maritime activities without incorporating land planning into it. This dichotomy may result in conflicts and inefficiencies, as observed by Innocenti and Musco, who contend that administrative boundaries inadequately represent land-sea interactions, hence requiring a unified framework for integrated administration (5)[5]. The absence of a cohesive strategy may lead to disjointed decision-making that neglects the interrelationships between terrestrial and marine environments (5)[5].

Furthermore, socio-cultural elements significantly influence land-sea interactions. Pikner et al. stress how important it is to include sociocultural values in maritime spatial planning because these values can affect how stakeholders are involved and how well planning processes work (6)[6]. Comprehending local cultural factors is crucial for promoting collaboration among stakeholders and ensuring that planning decisions align with community needs and values (6)[6]. Howells and Ramirez-Monsalve argue for this point of view by looking at the problems that happen when Denmark's land-based and sea-based planning systems don't work together. They stress the need for unified management plans that include both land and sea (7)[7].

The legislative framework substantially influences the amalgamation of terrestrial and marine spatial planning. The European Union's Maritime Spatial Planning Directive requires member states to account for land-sea interactions in their marine spatial plans, promoting a comprehensive approach to coastal management (8)[8]. However, Kidd et al. pointed out that many current planning processes still don't properly take these connections into account, which gets in the way of sustainable development efforts (8)[8]. Not all land-based planning principles apply directly to marine settings, which makes it challenging to change land-based planning models to fit the unique features of these settings (9)[9].

Indonesia, through the RZWP3K, has tried to integrate land and sea planning, although it is only limited to coastal areas, using the ICZM approach. This approach emphasises the need for interdisciplinary strategies that protect natural ecosystems while promoting economic development. According to (10)[10], ICZM is especially important in Indonesia because the coastal zone is always changing and is home to both land and sea species. It also involves a lot of different people. The authors argue that effective ICZM can enhance ecosystem resilience and support sustainable livelihoods for coastal communities. However, land and sea integration is not only needed in coastal areas but also on land, including urban areas— both urban areas located on the coast and urban areas bordering coastal areas. Amri et al. emphasised that coastal urban areas, such as those in Indonesia, face unique challenges due to rapid urbanisation. The increasing rate of urbanisation in coastal cities, which includes 150 in Indonesia, requires a comprehensive understanding of land use and its ecological implications (11)[11]. This urban expansion often causes significant changes to coastal ecosystems, resulting in habitat loss and increased vulnerability to climate change impacts, such as sea level rise and flooding. Doxa et al. also state that the impact of urbanisation on coastal ecosystems cannot be overstated. Doxa et al. point out that the expansion of coastal cities leads to biodiversity loss, making it imperative to prioritise conservation areas to protect coastal plant diversity (12)[12]. This need for conservation is also echoed by Suwarlan et al., who discuss the detrimental impacts of urban expansion on mangrove forests and loss of ecosystem function (13)[13]. The degradation of these important ecosystems not only threatens biodiversity but also exacerbates flood risk and other environmental hazards. Climate change impacts, particularly sea level rise and land subsidence, further complicate land-sea integration efforts in Indonesia. (14)[14] say that groundwater extraction and urban development make land subsidence worse, which in turn raises sea levels in coastal areas, making flooding more likely and coastlines moving back.

Thus, integration between land and sea in Indonesia is an important aspect of environmental management, especially given Indonesia's unique geographical characteristics as an archipelago. This integration is crucial for sustainable development, conservation, and addressing the challenges posed by climate change and anthropogenic activities. Spatial planning is expected to be one of the tools for integrating land and marine planning, especially in an archipelagic country like Indonesia, where the interaction between land and marine environments is critical for sustainable development and environmental management, as well as facilitating coordinated management of land and sea resources.

2. Materials and Methods

- Materials and Methods

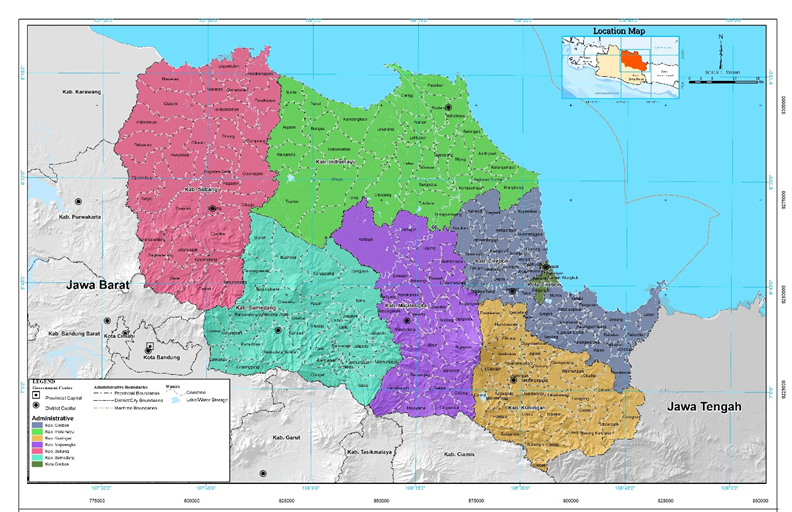

Rebana Metropolitan Area is the third metropolitan area in West Java Province after Bodebek Metropolitan (Bogor-Depok-Bekasi) and Greater Bandung Metropolitan. Administratively, it consists of seven regencies/cities, namely Cirebon City, Cirebon Regency, Majalengka Regency, Sumedang, Kuningan Regency, Indramayu Regency, and Subang Regency. It is located in the north/northeast region of West Java Province.

Currently, the Rebana Metropolitan Area has not considered oceans in its development plans or programmes. This can be seen from the five master plans that have been prepared that have not utilised ocean and ocean resources. The five master plans are a master plan for the provision and improvement of road transportation infrastructure (toll roads and road construction and improvement), a master plan for the provision and improvement of transportation infrastructure (land transportation network system), a master plan for the provision and improvement of basic infrastructure (settlement and sanitation infrastructure), a master plan for the development and provision of water resources infrastructure (dams, flood control, irrigation), and a master plan for the development of other infrastructure (improving the quality of human resources, regional competitiveness, health facilities and infrastructure, energy infrastructure, and industrial area development).

Although one of the strategies used to develop the Rebana Metropolitan Area is through the development of 13 new industrial cities, one of which is the Patimban maritime city located in Subang Regency. On the north coast of West Java, the industrial cities of Cirebon, Krangkeng, Balongan, Losarang, and Patrol are being built. The Patimban International Port is also being built as an economic hub for West Java, linked to the development of the Cirebon Port. However, all of these plans are still focused on land-based growth and have not yet considered how to combine land-based and marine-based growth. For example, Patimban Port and Cirebon Port are planned to be connected via toll roads without utilising the shipping lanes that cross the Rebana Metropolitan Area. This further strengthens the urgency of this area 's integration of land and sea spatial planning.

Figure 1. Administrative boundary of Rebana Metropolitan Area

The first step is the identification of the stakeholders who will be the resource persons for this research. Actors were selected based on their role and authority in spatial planning in the Rebana Metropolitan Area at the provincial level. Agencies that are only at the provincial level were selected because the lowest level of marine affairs is the authority of the province. This can be seen from the preparation of RZWP3K documents, which only exist at the national and provincial levels, not up to the district/city level.

Respondents came from seven agencies that have a role in spatial planning, both on land and at sea, namely the Office of Highways and Spatial Planning, the Office of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, the Regional Development Planning Agency, the West Java Provincial Transportation Agency, the Environment Agency, the Regional Disaster Management Agency, and, of course, the Rebana Metropolitan Management Authority.

The goal of this study is to find out what factors affect the implementation of a certain spatial planning policy. This means looking at the current methods, steps, and systems for spatial planning that are important for planning management. These include integrated land-sea management, which is necessary to make sure that planning processes take into account both the land and sea environments completely. Reuter et al. emphasise that successful integrated land and sea management necessitates a systematic methodology encompassing planning, execution, and continuous oversight (15)[15]. This method aids in recognising possible conflicts and synergies between terrestrial and marine applications; hence, it enhances decision-making efficacy. These planning management can be broken down into three dimensions: the policy dimension (since planning products are public policy products), the planning process integration dimension, and the environmental dimension. The planning process dimension is analyzed through the identification of planning procedures, implementation mechanisms, monitoring mechanisms, and evaluation mechanisms. The policy dimension is seen from policy integration, coordination mechanisms, distribution of authority, and public participation, both from the policy formulation process to its implementation. The integration aspect of the planning process can be seen in how data is used to make plans, how management, monitoring, and evaluation are all unified, and how the public is involved in both the planning and implementation phases. Meanwhile, the environmental dimension is identified from environmental documents and identification of potential disasters.

After these three dimensions are turned into variables, variables that impact spatial planning on land, at sea, and in combination with both will be found. The selection of these variables is done through structural analysis using the MICMAC method. (16)[16] stated that the use of the MICMAC method will help to identifying the main variables that influence and are influenced in a system and reveal the causal chain of a system. The process involves mapping the relationship between variables and the relevance of these variables in explaining a system

The level of relationship between variables is assessed on a scale: 0 = no relationship; 1 = weak relationship; 2 = moderate relationship; 3 = strong relationship; and P = potential influence (cannot be determined). The result of the relationship assessment will identify the relationship between variables into three groups of influence, namely: direct influence, indirect influence, and potential influence. Direct influence occurs if one variable affects another variable directly without going through another variable. Indirect influence occurs if one variable affects another variable, and the other variable then affects another variable again. Potential influence occurs if the influence of one variable conflicts with another variable. Meanwhile, if there is no direct effect of one variable on another, it is said to have no effect.

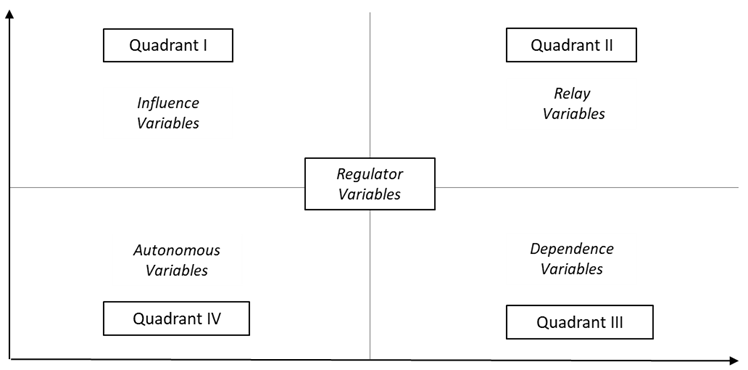

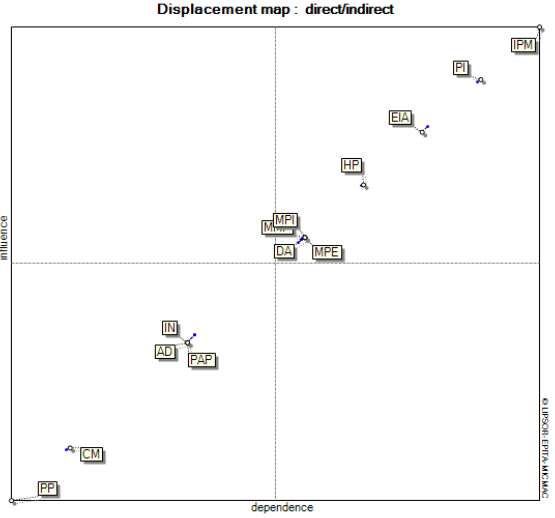

Mapping variables in MICMAC will result in four quadrants, each of which explains the status, role, and implications of each variable in the quadrant. Each variable position shows the different roles of each variable in the system. There are four main classifications for variables, namely: 1) influence variable, also called determinant variable, in quadrant I; 2) in quadrant II, relay variable 3) dependence or output variable in quadrant III; and 4) autonomous or excluded variable in quadrant IV (16)[16]. Meanwhile, regulator variables are said to have moderate influence and dependence on the system and act as levers.

Figure 12. Variable Mapping in MICMAC (16)[16].

Thus, in this study, the MICMAC analysis was conducted with the following steps.

- Determining variables that are likely to influence the spatial planning process, including land and marine spatial planning as part of the one spatial planning policy.

Table 1. Variables affecting spatial planning

Variables affecting spatial planning.

|

Dimension |

Variables |

References |

|

Policy |

Policy Integration (PI) |

|

|

Coordination Mechanism (CM) |

||

|

Authority Distribution (AD) |

||

|

Integration of planning processes |

Data Availability (DA) |

[1][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] |

|

Planning Approaches and Procedures (PAP) |

||

|

Mechanism for Plan Implementation (MPI) |

||

|

Monitoring/Control Mechanism Plan (MMP) |

||

|

Mechanism of Plan Evaluation (MPE) |

||

|

Integrated Planning Management (IPM) |

||

|

Institution (IN) |

||

|

Public Participation (PP) |

||

|

Environment |

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) |

|

|

Hazard Potential (HP) |

||

|

Dimension |

Variables |

References |

|

Policy |

Policy Integration (PI) |

(17); (18); (19); (20); (21); (22) |

|

Coordination Mechanism (CM) |

||

|

Authority Distribution (AD) |

||

|

Integration of planning processes |

Data Availability (DA) |

(23); (24); (25); (26); (18); (27); (28) (2014); (1); (21); (29) |

|

Planning Approaches and Procedures (PAP) |

||

|

Mechanism for Plan Implementation (MPI) |

||

|

Monitoring/Control Mechanism Plan (MMP) |

||

|

Mechanism of Plan Evaluation (MPE) |

||

|

Integrated Planning Management (IPM) |

||

|

Institution (IN) |

||

|

Public Participation (PP) |

||

|

Environment |

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) |

(24); (26); (18); (30); (31); (32) |

|

Hazard Potential (HP) |

- Filling in the variable linkage value cells

- The value is the agreement of the experts.

- The matrix agreement value is taken from the choice of the most values (mode).

- The score is between 0 - 3 with score criteria: 0: no relationship; 1: weak relationship; 2: average relationship; 3: strong relationship.

Table 2. Filling in Value Cells on Data Requirements

Filling in Value Cells on Data Requirements.

|

|

PI |

CM |

AD |

DA |

PAP |

MPI |

MMP |

MPE |

IPM |

IN |

PP |

EIA |

HP |

|

PI |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CM |

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AD |

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DA |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PAP |

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MPI |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MMP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MPE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

IPM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

IN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

PP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

EIA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

HP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

Based on the results of these data calculations, the variables studied to identify spatial planning were grouped into four quadrants based on their dependency and impact categories.

Table 3. Variable

Variable Types, Roles, Status and Implications

Types, Roles, Status and Implications (16)

[16].

|

Variable Type |

Variable Roles and Status |

Implications |

|

Influence Variables |

Very influence with little dependency |

A critical element in the system because it can act as a key system. The influence of other variables on this variable is not transmitted to the system. |

|

Relay Variables |

Influenced but highly dependent, describing an unstable variable |

Describes the instability of a system. Any change in this variable has serious consequences for other variables in the system. |

|

Dependance Variables |

Has little influence but high dependency |

This variable is quite sensitive to changes that occur in the influence variables and in the relay variables. |

|

Autonomous (Excluded) Variables |

Low impact, low dependency |

Has little potential to cause change. This variable is also excluded because it does not stop the operation of a system or use the system itself. |

|

Regulator Variables |

Has moderate influence and dependency |

Acts as a lever |

The data used is primary, taken from key informant interviews and determined based on their authority in land and sea spatial planning.

3. Results

Variable categories based on the strength of influence and direct dependence on other variables.

|

Influence Variable |

Relay Variable |

- Results

This study looks at four things: (1) strategic factors that affect how one spatial planning policy is put into place; (2) variables that have direct effects on each other ; (3) variables that have indirect effects on each other; and (4) changes in variables based on these effects and dependencies.

3.1. Analysis of strategic attributes in the implementation of one spatial planning policy

Strategic attributes in the implementation of one spatial planning policy are obtained from the results of the Matrix of Direct Influence (MDI) analysis. The numbers in the MDI matrix are the opinions of people who work for different government agencies that are allowed to plan space in the Rebana Metropolitan Area and know enough about its growth to give their honest opinions.

Table 4. Variable categories based on the strength of influence and direct dependence on other variables

Dependence Variable |

Autonomous Variable |

||

|

None |

|

None |

|

From the table above, it can be seen that none of the 13 variables analyzed fall into the influence variable category. There are 8 variables that are relay variables. This means that any change to these variables will effect the whole system, making them very sensitive and unstable when it comes to implementing a spatial planning policy. 5 variables fall into the autonomous variable category, which are variables affected by other variables. These five variables are also said to be excluded because without these variables, the implementation of one spatial planning policy can still run. Even if the implementation of one spatial planning policy fails, it is not caused by these five variables. There are no variables that fall into the dependent variable category.

3.2. Direct influence relationship between variables

3.2. Direct influence relationship between variables

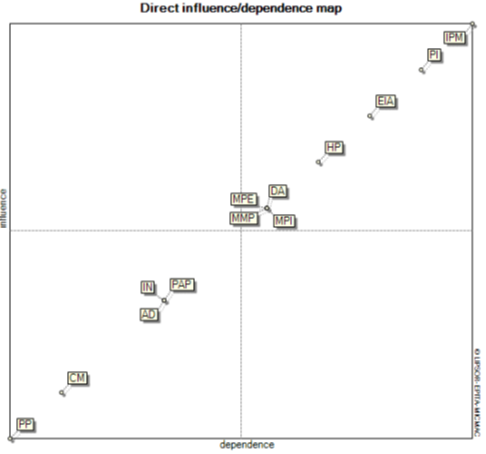

The position of variables towards other variables can be identified through grouping all variables into 4 quadrants based on the strength of direct influence and direct dependence on other variables.

Picture 3. Categorization of variables based on degree of influence and direct dependency on other variables.

Description :

|

PI |

: |

Policy Integration |

MPE |

; |

Mechanism of Plan Evaluation |

|

CM |

: |

Coordination Mechanism |

IPM |

: |

Integrated Planning Management |

|

AD |

: |

Authority Distribution |

IN |

: |

Institution |

|

DA |

: |

Data Availability |

PP |

: |

Public Participation |

|

PAP |

: |

Planning Approaches and Procedure |

EIA |

: |

Evironmental Impact Assessment |

|

MPI |

: |

Mechanism for Plan Implementation |

HP |

: |

Hazard Potential |

|

MMP |

: |

Monitoring/Control Mechanism Plan |

|

|

|

Table 5. Matrix of direct influence (MDI)

Matrix of direct influence (MDI).

|

No |

Variable |

Total number of rows |

Total number of columns |

|

1 |

Policy Integration |

34 |

34 |

|

2 |

Coordination Mechanism |

27 |

27 |

|

3 |

Authority Distribution |

29 |

29 |

|

4 |

Data Availability |

31 |

31 |

|

5 |

Planning Approaches and Procedures |

29 |

29 |

|

6 |

Mechanism for Plan Implementation |

31 |

31 |

|

7 |

Monitoring/Control Mechanism Plan |

31 |

31 |

|

8 |

Mechanism of Plan Evaluation |

31 |

31 |

|

9 |

Integrated Planning Management |

35 |

35 |

|

10 |

Institutions |

29 |

29 |

|

11 |

Public Participation |

26 |

26 |

|

12 |

Environmental Impact Assessment |

33 |

33 |

|

13 |

Hazard Potential |

32 |

32 |

Interpretation:

High row sum: Indicates a variable has a strong influence on other variables in the system.

High column sum: Represents a variable that is heavily influenced by other variables in the system

.

An MDI row and column summary is a table that adds up each row and column in the Direct Influence Matrix (MDI). The MDI is used to figure out how much different variables in a system affect and depend on each other. Basically, it gives a quick look at how each variable affects and depends on the others based on the relationships in the MDI matrix. The values in each row and column of the MDI matrix are added up to find the variables that have the most overall influence (high row sum) and the variables that depend on others the most (high column sum).

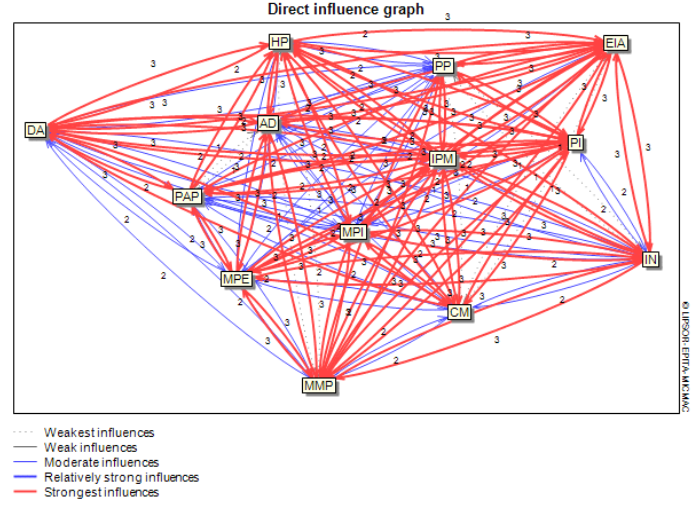

Picture 4. Direct influence graph.

The absence of variables that are key variables is emphasized by the image of the direct influence graph, which shows the relationship of variables that strongly influence other variables. The more lines that go into a variable, the stronger the attribute is influenced or dependent on other attributes. More lines from an attribute mean a stronger influence on other variables.

Some of the factors that have the biggest impacts on how well a spatial planning policy is carried out are policy integration, data availability, monitoring/control plan mechanisms, plan evaluation mechanisms, integrated planning management, environmental impact assessment, and hazard potential. These are shown in the direct influence graph. However, the value of these variables is not high enough to classify them as influence variables; they are more appropriately classified as relay variables.

3.3. Indirect Influence Relationship between Variables

3.3 Indirect influence relationship between variables

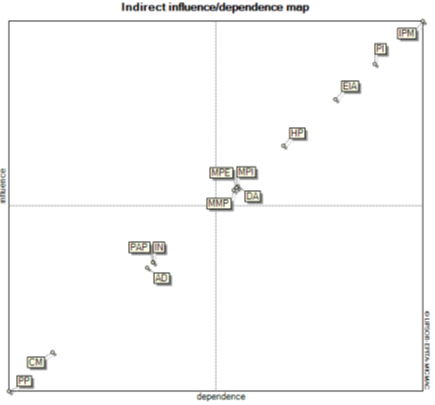

The positions of 13 variables are not too different from those seen in the analysis of direct influence relationships between variables. This is shown by the finding of indirect influence relationships between variables. What is different is only the position of the data availability, institutions, and coordination mechanism variables that have changed their position.

Influence relationships between variables are obtained from the degree or rating of influence obtained through iteration of the Boolean matrix (16)[16]. The Indirect Influence/Dependence Matrix (MII) is derived from the MDI by increasing the power through the number (specified as 'n') of successive iterations. Like MDI, MII, the number of columns represents the degree of instability of that metric, while the number of rows indicates the extent of influence that metric has, indirectly, on other.

Picture 5. Categorization of variables based on degree of influence and indirect dependency on other variables

Table 6. Matrix of indirect influence (MII)

Matrix of indirect influence (MII).

|

No |

Variables |

Total number of rows |

Total number of columns |

|

1 |

Policy Integration |

980341 |

980341 |

|

2 |

Coordination Mechanism |

800494 |

800494 |

|

3 |

Authority Distribution |

853266 |

853266 |

|

4 |

Data Availability |

903989 |

903989 |

|

5 |

Planning Approaches and Procedures |

856591 |

856591 |

|

6 |

Mechanism for Plan Implementation |

903117 |

903117 |

|

7 |

Monitoring/Control Mechanism Plan |

901625 |

901625 |

|

8 |

Mechanism of Plan Evaluation |

903164 |

903164 |

|

9 |

Integrated Planning Management |

1007158 |

1007158 |

|

10 |

Institutions |

856519 |

856519 |

|

11 |

Public Participation |

776141 |

776141 |

|

12 |

Environmental Impact Assessment |

958335 |

958335 |

|

13 |

Hazard Potential |

929350 |

929350 |

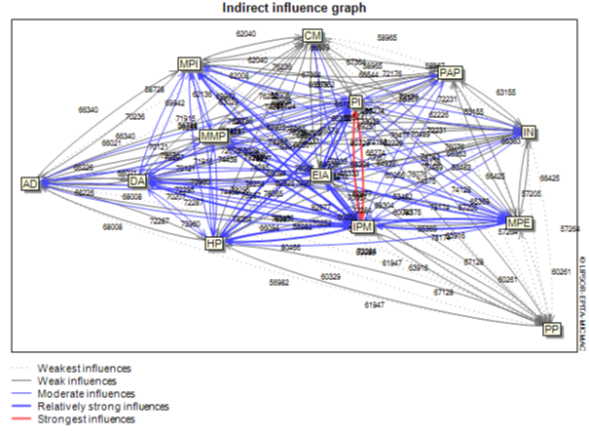

Picture 6. Indirect influence graph.

The strongest relationship between indirect influence is still the integrated planning management and policy integration, which is similar to what was found when the direct relationship between variables was looked at. This shows that the relationships between variables, both direct and indirect, result from a stable system.

3.4. Shifting Variables based on Influence and Dependency

3.4 Shifting variables based on influence and dependency

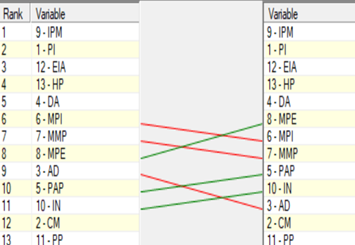

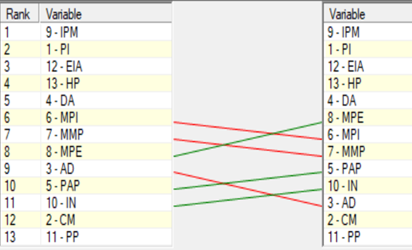

After mapping the interactions between variables, the next step is to identify changes in their ranking based on influence and dependency. This change shows where the variable rank was in the starting situation (MDI matrix) and after MDII has done a Boolean iteration (16), (33)[16][33].

|

|

|

Picture 7. Classify variables according to their influence and dependence

Classify variables according to their influence and dependence.

The above graph shows that the order of some variables has changed. For example, the mechanism for the plan implementation variable fell from sixth to seventh place after taking into account indirect influence factors. Similarly, the monitoring/control mechanism plan variable, which was originally in the 7th position, dropped to the 8th position, and the authority distribution variable, which was originally in the 9th position, dropped to the 11th position. On the other hand, some variables increased in order, such as the mechanism of plan evaluation, which was originally in the 8th position, increased to the 6th position; the planning approach and prosedures variable, which was originally in the 10th position, became the 9th position; and the institution variable, which was originally in the 11th position, became the 10th position.

From a dependence perspective, the three primary variables—integrated planning management policy integration and environmental impact assessment—consistently rank among the top three. Some variables have decreased by one level, such as the mechanism for plan implementation and monitoring/control mechanism plan variables, while the authority distribution variable has decreased by 2 ranks after the MDII iteration. While the mechanism of plan evaluation variable has increased by 2 levels, the planning approaches and procedures and institution variables have increased in rank by 1 level after considering the effect of the MDII iteration.

Picture 8. Displacement map

In the figure, the dotted line shows the change in the position of the variable from the initial position to the final position after accounting for indirect effects. These shifts are still in the same quadrant, although they change in magnitude.

After taking indirect influences into account, the position of the variables tends not to change—either the influence or the degree of dependency from direct to indirect influences. Although the monitoring/control mechanism plan, mechanism for plan implementation, and data availability variables have slightly shifted towards quadrant I, their positions remain in quadrant II. This shows that the system is stable.

4. Discussion

- Discussion

One intriguing thing that this study showed was that, based on the preferences of people who have power over spatial planning in the Rebana Metropolitan Area, none of the 13 variables that were looked at are the main variable. This means that none of them are very dependent on the other variables. Eight factors affect one spatial planning policy but depend on other factors a lot. These factors are integrated planning management, policy integration, environmental impact analysis, potential hazards, plan implementation mechanisms, plan evaluation mechanisms, plan monitoring/control mechanisms, and data availability. This means that all eight variables have an equal role in realizing a spatial planning policy.

Integrated planning management and policy integration, which have the highest scores as the most influential variables, have the same goal of increasing efficiency, coherence, and effectiveness in the decision-making process. By fostering cross-sectoral collaboration and optimizing resource allocation, organizations can better address complex issues while achieving their strategic goals. Integrated systems that are being developed with the help of technology will make these connections even stronger, leading to more responsive government and better results in public administration (34), (35), (36)[34][35][36].

(37)[37] says that integrated planning management is a way of coordinating different planning processes across different areas and levels of government in a way that leads to long-lasting results. On the other hand, policy integration involves harmonizing different policy areas to improve coherence and effectiveness in governance (38)[38]. The Rebana Metropolitan Area, which consists of 7 districts/city in West Java Province, has various spatial plans at the district/city level (district/city spatial plans and detailed spatial plans) and provincial level (provincial spatial plans). This does not include development plans owned by the Rebana Metropolitan Management Agency, as well as other sectoral plans, such as regional long-term and medium-term development plans that are closely related to spatial plans. Because of this, it makes sense to focus on integrated planning management and policies in order to create one spatial planning policy. This is because integrated planning management can adapt to different institutional, sectoral, and spatial settings. As (39)[39] pointed out, integration between different types of planning is needed to make things run more smoothly and efficiently. This integration is critical to address the interconnectedness of land and resource use, especially in areas facing rapid development pressures.

Stakeholders in Rebana Metropolitan spatial planning perspective that current development must be carried out with the principle of sustainable development. This can be seen from the importance of environmental impact analysis variables in realizing one spatial planning policy. It is important to combine environmental impact assessments with integrated planning processes so that environmental factors are properly taken into account when making decisions about spatial planning. This will help promote sustainable development and reduce negative environmental effects. This integration is particularly relevant in coastal areas, where competing interests such as tourism, agriculture, and conservation often clash (40)[40]. Another reason for the importance of environmental impact assessment is that the coastal areas of West Java, Indonesia, are highly vulnerable to various natural disasters, including tsunamis, floods, and coastal erosion. This vulnerability is exacerbated by a combination of geological, meteorological, and socioeconomic factors.

Four other variables that have considerable dependency on each other are plan implementation mechanisms, plan evaluation mechanisms, plan monitoring/control mechanisms, and data availability. The first three variables are part of a continuous process in spatial planning in Indonesia as stated in Government Regulation No. 21 of 2021 on the Arrangement of Spatial Planning. And of course, spatial planning requires data in the process. Data plays an important role in spatial planning, as it informs the decision-making process, enhances stakeholder engagement, and supports the development of sustainable urban environments. The integration of different types of data—from environmental assessments to socio-economic indicators—allows planners to create comprehensive strategies that can address a wide range of urban development challenges. Effective data integration is needed to harmonize these policies and improve the resilience of small cities (41)[41]. This highlights the need for comprehensive data systems that can support coherent planning processes and facilitate stakeholder collaboration. Moreover, a data-driven approach can help overcome policy fragmentation and improve overall planning effectiveness (42)[42].

The other five variables are about how to coordinate, how power is shared, how planning works and what steps are taken, institutions, and public participation. These are called autonomous variables or excluded variables. These five variables have little influence on the implementation of a spatial policy. However, the variables of planning approaches and procedures, the distribution of authority, and institutions have a great deal of dependency on each other. These three variables are actually important aspects of effective spatial planning. Understanding how these elements interact can lead to more sustainable and efficient land and resource management. This synthesis explores the linkages between these components, drawing on various references that highlight their importance in spatial planning. Institutions play an important role in shaping planning approaches and the distribution of authority. These institutions provide the regulatory framework on which spatial planning is based (43)[43].

The variables of coordination mechanisms, distribution of authority, and institutions are closely related to governance. Governance structures play a critical role in the success of integrated spatial planning. This integration is especially important in areas where water management and spatial planning have historically been treated as separate domains (44)[44], as is the case in the Rebana Metropolitan Area. When talking about how complicated it is to govern interactions between land and sea, O'Hagan et al. say that good management needs to carefully balance the needs of different stakeholders and the rules that govern those interactions (45)[45]. This complexity is also noted by Pittman and Armitage, who highlight the need for appropriate boundaries in governance to effectively address land-sea relationships (46)[46]. Integration of governance across multiple scales is essential to ensure that management strategies are responsive to the unique challenges posed by land-sea interactions

5. Conclusions

- Conclusions

There aren't any variables that become key variables, which means that all variables—especially those that are part of relay variables—work together to carry out one spatial planning policy in the Rebana Metropolitan Area. Bringing together land and sea spatial planning is challenging because of the complicated nature of spatial planning. To make it work, environmental impact assessment and integrated spatial planning need to be supported by integrated planning management and policy integration. This will help lower negative environmental impacts and increase positive outcomes, which will promote sustainable development.

The other five variables, although included in the excluded variables category, basically still have a role in realizing one spatial planning policy. One of the reasons why one spatial planning policy has not been realized is the absence of planning approaches and procedures that integrate land spatial planning and sea spatial planning. Current spatial planning approaches and procedures still prioritize spatial planning on land and do not integrate it with marine spatial planning. So, one way to make one spatial planning policy happen is to come up with integrated land and sea spatial planning approaches and procedures. These should be integrated not only in terms of maps but also in terms of what they plan to do.

Author Contributions: For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, R.R., E.R., A.F. and L.A.; methodology, R.R and A.F..; software, A.F.; validation, R.R., E.R., A.F. and L.A.; formal analysis, R.R and A.F.; investigation, R.R. resources, R.R. data curation, R.R. and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.; writing—review and editing, R.R., E.R., A.F. and L.A.; visualization, R.R and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

[26]

[27]

[28]

[29]

[30]

[31]

[32]

[33]

[34]

[35]

[36]

[37]

[38]

[39]

[40]

[41]

[42]

[43]

[44]

[44]

[45]

[46]

References

- Prima Yurista, Ananda and Agung Wicaksono, Dian. KOMPABILITAS RENCANA ZONASI WILAYAH PESISIR DAN PULAU-PULAU KECIL (RZWP3K) SEBAGAI RENCANA TATA RUANG YANG INTEGRATIF (Compatibility of Zoning Plan for Coastal Areas and Small Islands as Integrated Spatial Planning). Rechtsvinding. 2017, 6, 183.

- Matthew S. Merrifield; Ellen Hines; Xiaohang Liu; Michael W. Beck; Building Regional Threat-Based Networks for Estuaries in the Western United States. PLOS ONE. 2011, 6, e17407.

- Charles Loiseau; Lauric Thiault; Rodolphe Devillers; Joachim Claudet; Cumulative impact assessments highlight the benefits of integrating land-based management with marine spatial planning. Sci. Total. Environ.. 2021, 787, 147339.

- Shuo Wang; Jiaju Lin; Xiongzhi Xue; Yanhong Lin; Benefits and approaches of incorporating land–sea interactions into coastal spatial planning: evidence from Xiamen, China. Front. Mar. Sci.. 2024, 11, 1337147.

- Alberto Innocenti; Francesco Musco; Land–Sea Interactions: A Spatial Planning Perspective. Sustain.. 2023, 15, 9446.

- Tarmo Pikner; Joanna Piwowarczyk; Anda Ruskule; Anu Printsmann; Kristīna Veidemane; Jacek Zaucha; Ivo Vinogradovs; Hannes Palang; Sociocultural Dimension of Land–Sea Interactions in Maritime Spatial Planning: Three Case Studies in the Baltic Sea Region. Sustain.. 2022, 14, 2194.

- M. Howells; P. Ramírez-Monsalve; Maritime Spatial Planning on Land? Planning for Land-Sea Interaction Conflicts in the Danish Context. Plan. Pr. Res.. 2021, 37, 152-172.

- Kidd, S., Jones, H., Jay, S. Taking Account of Land-Sea Interactions in Marine Spatial Planning; Zaucha, J., Gee, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan, Cham: London, 2019; pp. 245-270.

- Marilena Papageorgiou; Stella Kyvelou; Aspects of marine spatial planning and governance: adapting to the transboundary nature and the special conditions of the sea. Eur. J. Environ. Sci.. 2018, 8, 31-37.

- Gumbira, Gugum and Harsanto, Budi. Decision Support System for An Eco-Friendly Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in Indonesia. Science Engineering and Information Technology. 2019, 9, 1177-1182.

- Amri S., Adrianto L., Bengen D., Kurnia R. SPATIAL PROJECTION OF LAND USE AND ITS CONNECTION WITH URBAN ECOLOGY SPATIAL PLANNING IN THE COASTAL CITY, CASE STUDY IN MAKASSAR CITY, INDONESIA. International Journal of Remote Sensing and Earth Science. 2017, 14, 95.

- Aggeliki Doxa; Cécile Hélène Albert; Agathe Leriche; Arne Saatkamp; Prioritizing conservation areas for coastal plant diversity under increasing urbanization. J. Environ. Manag.. 2017, 201, 425-434.

- Stivani Ayuning Suwarlan; Lee Yoke Lai; Ismail Said; A REVIEW OF AGRICULTURAL AND COASTAL CITIES IN INDONESIA IN FINDING URBAN SPRAWL PRIORITY PARAMETERS. Modul.. 2022, 22, 91-99.

- Karlina Triana; A'An Johan Wahyudi; Sea Level Rise in Indonesia: The Drivers and the Combined Impacts from Land Subsidence. ASEAN J. Sci. Technol. Dev.. 2020, 37, 115-121.

- Kim E. Reuter; Daniel Juhn; Hedley S. Grantham; Integrated land-sea management: recommendations for planning, implementation and management. Environ. Conserv.. 2016, 43, 181-198.

- Fauzi, A. Teknik Analisis Keberlanjutan; Fauzi, A, Eds.; PT. Gramedia Pustaka Utama: Jakarta, 2019; pp. 27-51.

- Shi C, Hutchinson S, Yu L, Xu S. Towards a sustainable coast: an integrated coastal zone management framework for Shanghai, People's Republic of China. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2001, 44, 411-427.

- Maesaroh S, Barus B, Laode Syamsul Iman. Analysis of Coastal Areas Utilization in Pandeglang District, Banten Province. Jurnal Tanah Lingkungan. 2013, 15, 45-51.

- Cominac D, Wiranto S, Said B. Sinergisme Rencana Zonasi Wilayah Pesisir dan Pulau-Pulau Kecil (RZWP3K). Jurnal Keamanan Maritim. 2020, 6, -.

- Prima Yurista A, Sosio Yusticia J. MENINJAU PERENCANAAN PEMANFAATAN PULAU-PULAU KECIL DI KABUPATEN GUNUNGKIDUL DALAM PERSPEKTIF PENATAAN RUANG YANG INTEGRATIF. Mimbar Hukum. 2020, 32, 436-449.

- Maciej Nowak; Giancarlo Cotella; Przemysław Śleszyński; The Legal, Administrative, and Governance Frameworks of Spatial Policy, Planning, and Land Use: Interdependencies, Barriers, and Directions of Change. Land. 2021, 10, 1119.

- Abdullah Radwan Arabeyyat; Jamal Ahmad Alnsour; Sakher A. I. A L-Bazaiah; Mahmoud A. Al-Habees; Managing Urban Environment: Assessing the Role of Planning and Governance in Controlling Urbanization in the City of Amman, Jordan. J. Environ. Manag. Tour.. 2024, 15, 263-271.

- Thia-Eng, Chua. The essential elements of science and management in coastal environmental managements. Hydrobiologia. 1997, 352, 159-166.

- A.H. Pickaver; C. Gilbert; F. Breton; An indicator set to measure the progress in the implementation of integrated coastal zone management in Europe. Ocean Coast. Manag.. 2004, 47, 449-462.

- Brian Shipman; Tim Stojanovic; Facts, Fictions, and Failures of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Europe. Coast. Manag.. 2007, 35, 375-398.

- M.E. Portman; L.S. Esteves; X.Q. Le; A.Z. Khan; Improving integration for integrated coastal zone management: An eight country study. null. 2012, 439, 194-201.

- Hurliman A, March A. The role of spatial planning in adapting to climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Climate Change. 2012, 3, 477-488.

- Małgorzata Krajewska; Sabina Źróbek; Maruška Šubic Kovač; The Role of Spatial Planning in the Investment Process in Poland and Slovenia. Real Estate Manag. Valuat.. 2014, 22, 52-66.

- Septian Anugrah; Sutran Sutran; Laode M Faisal; Andrinal Andrinal; Renny Agrianty; Andi Zulfikar; Dony Apdillah; Analisis Keselarasan Integrasi RZWP3K dan RTRW Provinsi Kepulauan Riau (Kasus: Lingkungan Pesisir Pulau Bintan). J. Mar. Res.. 2022, 11, 455-466.

- Melissa R. Poe; Karma C. Norman; Phillip S. Levin; Cultural Dimensions of Socioecological Systems: Key Connections and Guiding Principles for Conservation in Coastal Environments. Conserv. Lett.. 2013, 7, 166-175.

- Michelle Voyer; Natalie Gollan; Kate Barclay; William Gladstone; ‘It׳s part of me’; understanding the values, images and principles of coastal users and their influence on the social acceptability of MPAs. Mar. Policy. 2015, 52, 93-102.

- Anna Katarzyna Andrzejewska; Challenges of Spatial Planning in Poland in the Context of Global Climate Change—Selected Issues. Build.. 2021, 11, 596.

- Tatan Sukwika; Penentuan Faktor Kunci Untuk Pengembangan Pengelolaan TPST-Bantargebang Berkelanjutan: Pendekatan MICMAC. J. Tataloka. 2021, 23, 524-535.

- Amirudin A, Felta Wijaya A, Yossomsakdi S. Integrated Planning Approach Among Planng Scale and Sector (A Case Study of Minalang City's Vision as the City Education). Wacana. 2014, 17, -.

- Philipp Rode; Urban planning and transport policy integration: The role of governance hierarchies and networks in London and Berlin. J. Urban Aff.. 2017, 41, 39-63.

- Joanna Vince; Maree Fudge; Liam Fullbrook; Marcus Haward; Understanding policy integration through an integrative capacity framework. Policy Soc.. 2024, 43, 381-395.

- D R Indrawati; D P Simarmata; Lake Toba catchment management in an integrated manner: a necessity. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci.. 2023, 1266, -.

- Jeroen J. L. Candel; Robbert Biesbroek; Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sci.. 2016, 49, 211-231.

- Min Zhao; Haixia Pan; Construction logic and implementation strategies of spatial planning system of China. Front. Urban Rural. Plan.. 2023, 1, 1-14.

- Rigonato MB, Mello K de, Valente RA. The Importance of Integrating Financial Incentives and Command and Control Instruments to Protect Water Quality. In: III SEVEN INTERNATIONAL MULTIDISCIPLINARY CONGRESS. Seven Congress; 2023.

- Setyono JS, Handayani W, Rudiarto I, Esariti L. Resilience Concept in Indonesian Small Town Development and Planning: a Case of Lasem, Central Java. In: E3s Web of Conferences [Internet]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf

- Anita Kokx; Tejo Spit; Increasing the Adaptive Capacity in Unembanked Neighborhoods? An Exploration into Stakeholder Support for Adaptive Measures in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Am. J. Clim. Chang.. 2012, 01, 181-193.

- Maciej J. Nowak; Renato Monteiro; Jorge Olcina-Cantos; Dimitra G. Vagiona; Spatial Planning Response to the Challenges of Climate Change Adaptation: An Analysis of Selected Instruments and Good Practices in Europe. Sustain.. 2023, 15, 10431.

- T. Hartmann; P. Driessen; The flood risk management plan: towards spatial water governance. J. Flood Risk Manag.. 2013, 10, 145-154.

- Anne Marie O'Hagan; Shona Paterson; Martin Le Tissier; Addressing the tangled web of governance mechanisms for land-sea interactions: Assessing implementation challenges across scales. Mar. Policy. 2020, 112, 103715.

- Jeremy Pittman; Derek Armitage; Governance across the land-sea interface: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2016, 64, 9-17.