Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based algorithms, in particular, Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), have recently revolutionized image creation. Precise segmentation of lesions may contribute to an efficient diagnostics process and a more effective selection of targeted therapy. For example, an AI-based algorithm for the segmentation of pigmented skin lesions has been developed, which enables diagnosis in the earlier stages of the disease, without invasive medical procedures. With flexibility and scalability, AI can be also considered an efficient tool for cancer diagnosis, particularly in the early stages of the disease.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Machine Learning

- Virtual Reality

- Extended Reality

- Mixed Reality

- cardiology

- personalized medicine

- Metaverse

- Augmented Reality

1. Introduction

| AI/ML Model | Application Fields (In General) | Application Fields (In Cardiology) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANNs | classification, pattern recognition, image recognition, natural language processing (NLP), speech recognition, recommendation systems, prediction, cybersecurity, object manipulation, path planning, sensor fusion | prediction of atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarctions, and dilated cardiomyopathy detection of the structural abnormalities in heart tissues | [8] [9] |

| RNNs | ordinal or temporal problems (language translation, speech recognition, NLP image captioning), time series prediction, music generation, video analysis, patient monitoring, disease progression prediction | segmentation of the heart and subtle structural changes cardiac MRI segmentation |

[10] [11] |

| LSTMs | ordinal or temporal problems (language translation, speech recognition, NLP, image captioning), time series prediction, music generation, video analysis, patient monitoring, disease progression prediction | segmentation and classification of 2D echo images segmentation and classification of 3D Doppler images segmentation and classification of video graphics images and detection of the AMI in echocardiography |

[12] [13] |

| CNNs | pattern recognition, segmentation/classification, object detection, semantic segmentation, facial recognition, medical imaging, gesture recognition, video analysis | cardiac image segmentation to diagnose CAD cardiac image segmentation to diagnose Tetralogy of Fallot localization of the coronary artery atherosclerosis detection of cardiovascular abnormalities detection of arrhythmia detection of coronary artery disease prediction of the survival status of heart failure patients prediction of cardiovascular disease LV dysfunction screening prediction of premature ventricular contraction detection |

[14][15] [16] [17] [18] [19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] [31] [32] [33] [34][35] |

| Transformers | NLP, speech processing, computer vision, graph-based tasks, electronic health records, building conversational AI systems and chatbots | coronary artery labeling prediction of incident heart failure arrhythmia classification cardiac abnormality detection segmentation of MRI in case of cardiac infarction classification of aortic stenosis severity LV segmentation heart murmur detection myocardial fibrosis segmentation ECG classification |

[36][37] [38] [39][40][41][42] [43] [44] [45][46] [41][47][48] [49] [41] [50] |

| SNNs | pattern recognition, cognitive robotics, SNN hardware, brain–machine interfaces, neuromorphic computing | ECG classification detection of arrhythmia extraction of ECG features |

[51][52][53] [54][55][56] [57] |

| GANs | image-to-image translation, image synthesis, and generation, data generation for training, data augmentation, creating realistic scenes | CVD diagnosis segmentation of the LA and atrial scars in LGE CMR images segmentation of ventricles based on MRI scans left ventricle segmentation in pediatric MRI scans generation of synthetic cardiac MRI images for congenital heart disease research |

[58] [59] [60] [61] [62] |

| GNNs | graph/node classification, link prediction, graph generation, social/biological network analysis, fraud detection, recommendation systems | classification of polar maps in cardiac perfusion imaging analysis of CT/MRI scans prediction of ventricular arrhythmia segmentation of cardiac fibrosis diagnosis of cardiac condition: LV motion in cardiac MR cine images automated anatomical labeling of coronary arteries prediction of CAD automation of coronary artery analysis using CCTA screening of cardio, thoracic, and pulmonary conditions in chest radiograph |

[63][64] [65] [64] [64] [66] [67] [68] [69] [70] |

| QNNs | optimization of hardware operations, user interfaces | classification of ischemic heart disease | [20] |

| GA | optimization techniques, risk prediction, gene therapies, medicine development | classification of heart disease | [71] |

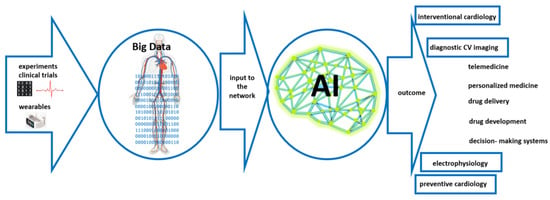

2. Artificial Intelligence-Based Support in Cardiology

2.1. Application of the You-Only-Look-Once (YOLO) Algorithm

2.2. Genetic Algorithms

The analysis of medical data can also be approached using metaheuristic methods such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) in particular, and Artificial Immune Systems (AISs) that search the possible solution space based on mechanisms taken from the theory of evolution and natural immune systems. GAs can also be used to improve diagnosis as well as the selection of targeted therapy in the field of cardiology. Reddy et al. [71] applied GAs to the diagnostics of early-stage heart disease, which has crucial implications in the selection of further therapy methods. For example, GAs allowed for the optimization of classification rules. As a consequence, the level of accuracy increased and the computational cost was reduced (due to the simplification of the selection process). GAs can also be applied to the determination of personalized parameters of the cardiomyocyte electrophysiology model [76]. Here, the Cauchy mutation was applied. In most cases, GAs were used to limit the number of parameters that are then used as input to another AI-based algorithm, such as a Support Vector Machine (SVM) [77][78]. Genetic Algorithms can effectively search for optimal segmentation solutions in the case of heart image segmentation, where anatomical structures may have different shapes. However, GAs may exhibit difficulties with complex limitations or domain-specific knowledge in cardiac image segmentation tasks. On the other hand, GAs can also be effective in the optimization of the input parameters to neural networks. They are inherently robust concerning noise and local optima. This is an important feature taking into account motion artifacts or imaging noise in cardiac image segmentation. A huge disadvantage of GAs is the cost of computing large search spaces or high-dimensional feature spaces, which is crucial, especially for real-time computations or in clinical settings (such as may occur in cardiology applications). Thus, finding the optimal parameter can be difficult and time-consuming.2.3. Artificial Neural Networks

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are networks whose structure and principle of operation are to some extent modeled on the functioning of fragments of the real nervous system (the brain) [79][80]. This computational invention contributes to the development of medical imaging, especially in cardiology, where their design, inspired by the human brain, enables them to interpret complex patterns within medical data effectively. ANNs consist of layers composed of several neurons, which apply specific weights and biases to the inputs. These neurons utilize non-linear activation functions that enable the network to detect complex patterns and relationships that linear functions might overlook. The output layer plays a pivotal role in making predictions or classifications based on the analysis, such as identifying signs of heart disease, classifying different cardiac conditions, or determining the severity of a disorder [81][82]. In cardiology, the ability to detect conditions accurately and at an early stage is of paramount importance, and the application of ANNs for the analysis of medical images is an important development in this area. Considering the high global prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, the application of ANNs in cardiac imaging may substantially improve diagnostic techniques [83]. ANNs provide an efficient computational tool to detect structural abnormalities in heart tissues. They also play a vital role in assessing cardiac function, evaluating important metrics such as ejection fraction, and analysis of blood flow patterns, essential for diagnosing heart failure or valvular heart disease. ANNs can automatically learn hierarchical features from raw image data without the need to manually extract features, which is beneficial for segmenting complex organs such as the heart. However, ANN application in the field of medical image processing requires converting two-dimensional images to one-dimensional vectors. This increases the number of parameters and increases the cost of calculation. However, as in the case of YOLO-based segmentation algorithms, an ANN-based approach also requires large and good-quality training data to provide high accuracy.2.4. Convolutional Neural Networks

Another neural network that has been applied to medical image processing is the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). As opposed to traditional neural networks such as ANNs, which typically process data in a straightforward, sequential manner, CNNs can discern spatial relationships within datasets. This is due to the way they are designed and constructed, intended as they are to maintain and interpret the spatial structure of input data, an attribute that is vital for the accurate assessment of medical images. For example, Roy et al. [14] applied CNNs to cardiac image segmentation to diagnose coronary artery disease (CAD). CNNs were used to analyze 2D X-ray images, significantly enhancing image segmentation accuracy and setting new standards in medical image analysis. Similarly, as in Gao et al. [84], Galea et al. [85] proposed combining U-Net and DeepLabV3+ CNN architectures for the segmentation of cardiac images from smaller datasets. Tandon et al. [86] applied CNNs in cardiology with a specific focus on cardiovascular imaging for patients with Repaired Tetralogy of Fallot (RTOF). A CNN originally designed for ventricular contouring was retrained and adapted to the complexities of RTOF. This enabled an increase in algorithm accuracy. In turn, Stough et al. [87] developed a fully automatic method for segmenting heart substructures in 2D echocardiography images using CNNs that was validated against a robust dataset, and Sander and Išgum [88] focused on enhancing the segmentation of cardiac structures in cardiac MRI. This method integrates automatic segmentation with an assessment of segmentation uncertainty to identify potential local failures. The measures of predictive uncertainty were calculated and trained by another CNN to detect local segmentation errors for potential expert correction. This approach combining automatic segmentation with manual correction of detected errors could significantly reduce the time required for expert segmentation. In the context of cardiology, fully connected layers of CNNs are responsible for synthesizing information to perform critical analytical tasks. These include classifying different cardiac conditions, detecting anomalies such as irregularities in heart size or shape, and making predictive assessments based on a comprehensive analysis of cardiac structure and function. CNNs are particularly good at handling complex datasets from various imaging modalities in cardiology, including MRI, CT scans, and ultrasound [89]. The strength of CNNs lies in their ability to handle high-dimensional data and to effectively capture the spatial structures within medical images in cardiology. This leads to more precise and comprehensive analyses of cardiac health. However, in the case of sparse or partial input data, their use is difficult and does not provide high prediction accuracy, while high segmentation accuracy is associated with high computational costs. Nor do CNNs take into account spatial relations in images which is important in the case of cardiology. To overcome this limitation, Capsule Networks (CNs) were introduced [90]. Their output is in the form of vectors that enable some spatial relations to be saved. The disadvantage of this approach is the lack of verification on a large dataset.2.5. Recurrent Neural Networks

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are known for their ability to model long-term dependencies and are crucial for capturing the intricate details of cardiac structures. Unlike traditional feedforward neural networks that process inputs in a one-directional manner, RNNs are designed to handle sequences of data. This is achieved through their internal memory, which allows them to retain information from previous inputs and use it in the processing of new data [91]. In the case of medical data in the form of echocardiography, and cardiac MRI segmentation, RNNs have shown promising performance [11]. They also excel in handling the sequential and temporal aspects of both MRI and CT data, crucial for monitoring dynamic changes in cardiac tissues over time [59]. In turn, Wahlang et al. [12] combined RNNs and their variations in Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) successfully in the segmentation and classification of 2D echo images, 3D Doppler images, and video graphic images. Wang and Zhang [39] also considered the segmentation of the left ventricle wall in four-chamber view cardiac sequential images. RNN was applied to provide detailed information for the initial image, while LSTM to generate the segmentation result: this approach increases accuracy. Another RRN application in the field of cardiology was presented by Muraki et al. [13]. Here, simple RNNs, LSTM, and other RNN variations (such as Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)) were successfully used to detect acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in echocardiography. RNNs have proven to be well suited to managing the sequential and temporal characteristics inherent in MRI and CT data, a capability that is essential for accurately tracking the dynamic alterations in cardiac tissues due to the possibility of effective capturing of long-range non-linear dependencies, such as modeling the risk trajectory of heart failure [92]. However, one limitation of RNNs is connected with vanishing or exploding gradients.2.6. Spiking Neural Networks

Calculations related to the analysis of cardiac data are very time-consuming and involve a great deal of computing resources. One alternative that can potentially reduce computational cost could be Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). Currently, SNNs are not yet as accurate in comparison to traditional neural networks: they have characteristics that are more similar to biological neurons [93]. They may also be advantageous in wearable and implantable devices for their energy efficiency and real-time processing capabilities. This makes them ideal for continuous cardiac monitoring, as they require less frequent recharging or battery replacement, a significant benefit for devices like cardiac monitors and pacemakers. For example, Rana and Kim [94] modify the synaptic weights such as to be binary. This operation provides a reduction in computational complexity and power consumption. This is crucial, especially in the context of wearable monitors where continuous monitoring is key but the constraints of power and computational resources are limiting factors. Their binarized SNN model may be a highly efficient alternative for ECG classification, setting a new standard in continuous cardiac health monitoring technologies. SNNs, however, are more computationally efficient (connected to the high level of computational speed and real-time performance). As a consequence, SNNs consume less energy, which translates into better use of hardware resources. However, their learning algorithms require improvement (in terms of accuracy gains), in comparison, for example, to the accuracies achieved by the application of CNNs [95]. In the case of SNNs, the requirement of increasingly powerful hardware is also of high importance. SNNs also have a significant limitation in practical applications due to the smaller number of available tools, libraries, and structures in comparison to other neural network types. SNNs also provide worse results in terms of accuracy compared to traditional approaches. To fully exploit the potential of SNNs, including detecting anomalies in biomedical signals and designing more detailed networks, the SNNs’ learning mechanisms/rules need to be improved.2.7. Generative Adversarial Networks

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are network architectures that consist of two core components: the generator and the discriminator. The generator shoulders the responsibility of creating data that faithfully emulates specific data (artificial data identical to real data) to cheat the discriminator. It initiates the process with an input of random noise, meticulously refining it through multiple layers of neural network architecture. Each layer integrated within the generator network fulfills a distinct role, harnessing techniques such as convolutional or fully connected layers. These layers operate cohesively to progressively metamorphose the initial noise input into an output that becomes increasingly indistinguishable from the target data. A discriminator is designed to distinguish artificial data (produced by a generator) from real data based on small nuances. Thus, the core concept of this solution is to train two networks that compete with each other. As a consequence, they are expected to produce more authentic data [96]. GANs seem to be promising computational tools to elevate patient care and improve clinical outcomes, in particular in the field of cardiology. First, the most important GAN application field is CVD diagnosis [58]. Retinal fundus images were used as input to the network. This approach led to the analysis of microstructural alterations within retinal blood vessels to pinpoint pivotal risk factors associated with CVD, such as Hypertensive Retinopathy (HR) and Cholesterol-Embolization Syndrome (CES). Moreover, the incorporation of a retrained ImageNet model for customized image classification further bolstered predictive accuracy. GANs have shown exceptional proficiency in handling complex and varied cardiac datasets. They generate highly realistic images, aiding training and research, particularly where access to real patient data is limited. GANs are instrumental in enlarging existing datasets and creating diverse and extensive data for training more accurate and robust diagnostic models. In addition to image generation, GANs are adept at image-to-image translation tasks, a significant feature in medical imaging [97]. They can transform MRI images into CT scans, offering different perspectives of the same anatomical structure without needing multiple imaging modalities. This is particularly beneficial in scenarios where certain imaging equipment might be unavailable. However, the main disadvantages of GANs are the complex training needed that does not necessarily lead to hoped-for results, a tendency to overfit, and high computational costs. Moreover, GANs are difficult to interpret, which is of key importance in medicine, especially in cardiology.2.8. Graph Neural Networks

If the data format is approached differently, as in non-Euclidean space in the form of graphs, it can be understood in terms of vertices (i.e., objects). Then, the concept of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can be applied [98]. All relations in this type of neural network are expressed as those between nodes and edges of the graph. These networks are designed to handle graph data that form a critical aspect in medical fields, especially when the intricate relationships and connections between data points are essential for accurate diagnosis and health condition analysis. This principle of operation is useful in medical imaging, especially in neuroimaging and molecular imaging, where understanding complex relationships is crucial [51][99]. In the field of cardiology, GNNs have been effectively employed in several key areas. They have been used in the classification of polar maps in cardiac perfusion imaging, a critical technique for assessing heart muscle activity and blood flow. Another significant application of GNNs in cardiology is the estimation of left ventricular ejection fraction in echocardiography. This measurement is vital for evaluating heart health, specifically in assessing the volume of blood the left ventricle pumps out with each contraction [63]. This allows for more accurate analyses through an understanding of the intricate graph structures of the heart’s imagery. GNNs are also being utilized in analyzing CT/MRI scans. This approach can also be used to interpret the relationships and structures within the scan, providing detailed insights into various conditions and helping in diagnosis and treatment planning [65]. GNNs provide a powerful tool for understanding and interpreting complex data structures, such as those found in medical image processing. One of the key strengths of GNNs is their adaptability to varying input sizes and structures, an essential feature in medical imaging where patient data can greatly differ. The architecture of GNNs is tailored to process and interpret graph-structured data, making it a powerful tool in areas such as medical image processing where data often forms complex networks. This specialized structure of GNNs sets them apart in their ability to handle data that is inherently interconnected, such as neurological networks or molecular structures. It is also worth stressing that GNNs were created for tasks that cannot be effectively solved by other types of networks based on input data in Euclidean space. However, GNNs are difficult to interpret. On the other hand, computational cost is also a crucial parameter. Here, QNNs may provide some insight, while the GA can effectively help in the optimization of the input parameters to neural networks.2.9. Transformers

One further type of neural network that has recently come into focus in the field of medicine concerns transformers. These learn rules based on the context and tracking the relations between the data. Originally, they were networks used for natural language processing (NLP). Their effectiveness in these tasks resulted in the development of transformers such as the Detection Transformer (DETR) for tasks related to vision analysis [100], the Swin-Transformer [101], the Vision Transformer (ViT) [102], and the Data-Efficient Image Transformer (DeiT) [102]. The DETR is dedicated to object detection which also includes manual analytical processes, and it uses CNN to learn 2D representations of the input data (images). In turn, the ViT converts input to a series of fixed-size non-overlapping patches and treats them as a token. Each of them encodes the spatial position of each part of the image to provide spatial information, while the spatial information of the pixels is lost during tokenization. However, ViTs require large training datasets. On the other hand, DeiTs also provide high accuracy in the case of small training datasets, while Swin-Transformers allow the cost of calculations to be reduced. They process an image divided into overlapping areas showing tokens at multiple scales with a hierarchical structure using a shifted window (local self-attention). The transformer principle of operation is based on the self-attention mechanism. This enables the network to decide on the importance of different parts of the input data for future prediction (i.e., weight). This may be beneficial for the evaluation of the relationships between different regions in medical images. The application of transformer networks allows for a deeper understanding of cardiac function, which aids in refining diagnostic methods and improving treatment strategies. For example, Jungiewicz et al. focused on stenosis detection in coronary arteries, comparing different variants of the Inception Network with the ViT [36]. They analyzed small fragments from coronary angiography videos, highlighting the role of dataset configuration in model performance. A key innovation in their approach is the use of Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) alongside Vision Transformers (VTs), which enhances the accuracy and reliability of stenosis detection. They also employed Explainable AI techniques to understand the differences in classification performance between the models. Their findings indicate that while Convolutional Neural Networks generally outperform transformer-based architectures, the gap narrows significantly with the addition of SAM to VTs. In some measures, the SAM-VT model even surpasses other models. It turned out that ViT can effectively be applied to diagnose coronary angiography. Zhang et al. [37] present a Topological Transformer Network (TTN) for automated coronary artery branch labeling in Cardiac CT Angiography (CCTA). The TTN, inspired by the success of transformers in sequence data analysis, treats vessel branch labeling as a sequence labeling learning problem. It introduces a unique topological encoding to represent spatial positions of vessel segments within the arterial tree, enhancing classification accuracy. The network also includes a segment-depth loss function to address the class imbalance between primary and secondary branches. The effectiveness of a TTN is demonstrated in CCTA scans, where it achieves unprecedented results, outperforming existing methods in overall branch labeling and side branch identification. TTNs mark a departure from traditional methods, representing the first transformer-based vessel branch labeling method in the field. The integration of this method into computer-aided diagnosis systems can enhance the generation of cardiovascular disease diagnosis reports, thereby improving patient outcomes in cardiac care. This approach significantly enhances the detection and analysis of myocardial ischemia and infarction by tracking wall-motion abnormalities in the left ventricle. The core innovation is the integration of a co-attention mechanism within the Spatial Transformer Network (STN), which improves feature extraction between frames for smoother motion fields and enhanced interpretability in noisy 3D echocardiography images. Additionally, a novel temporal regularization term guides the motion of the left ventricle, producing smooth and realistic cardiac displacement paths. The CA-STN outperforms traditional methods that rely on heavy regularization functions, marking a new standard in cardiac motion tracking. Strain analysis using the Co-Attention STNs aligns with matched SPECT perfusion maps, illustrating the clinical utility of 3D echocardiography for localizing and quantifying myocardial strain following ischemic injury. This study contributes a novel tool for cardiac imaging and opens new possibilities for early detection and interventions in myocardial injuries. Thus, an approach based on transformers in cardiological data segmentations offers advantages such as global context modeling, parallel processing, attention mechanisms, transfer learning, and interpretability for cardiac image segmentation. However, transformers process the input data sequentially, which may cause some important information to be missed and the segmentation performed (especially for tasks requiring precise localization of anatomical structures in heart images) to be inaccurate. Like CNN and the YOLO algorithm, this approach requires a large amount of good-quality data and the involvement of significant computational resources. Careful hyperparameter tuning and regularization techniques can overcome this disadvantage, but potentially increase the complexity of the training process.2.10. Quantum Neural Networks

Recently, some work has also been devoted to the development of quantum neural networks (QNNs) that are based on the idea of quantum mechanics [103][104]. These may have huge potential to speed up calculations and reduce the computational costs associated with them. This approach can be developed in two ways related to the segmentation of medical images. The first is the use of quantum circuits to train classical neural networks, and the second is the design and training of quantum networks, as proposed by Mathur et al. [81]. Indeed, Shahwar et al. [105] showed the potential of QNNs in the classification of Alzheimer’s detection, and Ullah et al. [20] proposed a quantum version of the Fully Convolutional Neural Network (FCNN) as applied to a challenge that concerned the classification of ischemic heart disease. This allowed for a prediction accuracy of over 80 percent. However, the approach based on quantum neural networks requires further improvement. When it comes to interventional practice, QNNs have the potential for stenosis detection in X-ray coronary angiography [106], and they can be also applied to selecting medicines for patients with high accuracy [107][108]. Thus, QNNs may also provide some insight into the reduction in computational cost.3. Evaluation Metrics in Medical Image Segmentation

Artificial Intelligence has the chance to become a high-precision tool in medicine. However, there are certain technical risks (TERs) connected with the application of AI in clinical and educational practice, including algorithm performance, legal regulation, and safety. For example, it is known that small, even imperceptible changes in the training dataset can drastically change the results of predictions, which in medicine can have very serious consequences and influence learning. The key to the evaluation of AI adaptability is to use an appropriate metric to assess the correctness and accuracy of different kinds of forecasts including clinical prognoses and for this to be understood by users [109]. For example, overfitting between training and testing datasets will reduce the accuracy of the algorithm. Other crucial factors that influence the qualitative efficiency of the AI-based algorithm’s dataset include data availability issues. However, even if developers do not have sufficient quantity and quality of data, cross-validation can be applied [110]. This procedure helps avoid overfitting by the selection of a subset. Thus, the choice of a proper evaluation metric depends on the specific task type. The binary classifier Dice coefficient (also called the Sørensen–Dice index) and the Index of Union (IoU) are most commonly used in medical image segmentation metrics. However, in the field of cardiology, accuracy is of particular concern.Moreover, an important element in improving the effectiveness of cardiology data segmentation is the collection of as much reliable, good-quality data as possible while keeping class balance in mind. This procedure should take into account input data diversity that helps AI models better generalize unseen cases while their reliability is improved. It is also necessary to provide diverse and representative input data whenever possible, which can help mitigate bias in AI-based algorithms. Another issue related to data is the application of the open data policy following UNESCO guidelines (especially for scientific applications, and research) so that more efficient AI algorithms can be developed in the area of cardiology. Moreover, compliance with ethical and bioethical standards in the collection, storage, and use of medical data is essential for the development of reliable AI systems in cardiology. As a consequence, the establishment of standards for the quality, integrity, and interoperability of cardiology data used in AI applications in cardiology as well as the development of the protocols for the validation and regulation of AI-based algorithms is of high importance. It is also necessary to develop guidelines on how to integrate artificial intelligence technologies into cardiology workflows as well as strategies for managing risks associated with the implementation of AI-based technologies in cardiology. Finally, it should be the responsibility of the cardiology community to ensure the control of results and feedback loops in the implementation of mechanisms for monitoring the performance of AI algorithms in cardiology and the collection of feedback from clinicians and patients.

References

- Boonstra, M.J.; Oostendorp, T.F.; Roudijk, R.W.; Kloosterman, M.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Loh, P.; Van Dam, P.M. Incorporating Structural Abnormalities in Equivalent Dipole Layer Based ECG Simulations. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 2690.

- He, B.; Hu, W.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, S.; Han, X.; Su, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L. Image Segmentation Algorithm of Lung Cancer Based on Neural Network Model. Expert Syst. 2021, 39, e12822.

- Evans, L.M.; Sözümert, E.; Keenan, B.E.; Wood, C.E.; du Plessis, A. A Review of Image-Based Simulation Applications in High-Value Manufacturing. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 1495–1552.

- Arafin, P.; Billah, A.M.; Issa, A. Deep Learning-Based Concrete Defects Classification and Detection Using Semantic Segmentation. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 23, 383–409.

- Ye-Bin, M.; Choi, D.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, J.; Oh, T.H. ENInst: Enhancing Weakly-Supervised Low-Shot Instance Segmentation. Pattern. Recognit. 2024, 145, 109888.

- Hong, F.; Kong, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Z. Unified 3D and 4D Panoptic Segmentation via Dynamic Shifting Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 1–16.

- Rudnicka, Z.; Szczepanski, J.; Pregowska, A. Artificial Intelligence-Based Algorithms in Medical Image Scan Seg-Mentation and Intelligent Visual-Content Generation-a Concise over-View. Electronics 2024, 13, 746.

- Sammani, A.; Bagheri, A.; Van Der Heijden, P.G.M.; Te Riele, A.S.J.M.; Baas, A.F.; Oosters, C.A.J.; Oberski, D.; Asselbergs, F.W. Automatic Multilabel Detection of ICD10 Codes in Dutch Cardiology Discharge Letters Using Neural Networks. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 37.

- Muscogiuri, G.; Van Assen, M.; Tesche, C.; De Cecco, C.N.; Chiesa, M.; Scafuri, S.; Guglielmo, M.; Baggiano, A.; Fusini, L.; Guaricci, A.I.; et al. Review Article Artificial Intelligence in Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography: From Anatomy to Prognosis. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6649410.

- Yasmin, F.; Shah, S.M.I.; Naeem, A.; Shujauddin, S.M.; Jabeen, A.; Kazmi, S.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Kumar, P.; Salman, S.; Hassan, S.A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in the Diagnosis and Detection of Heart Failure: The Past, Present, and Future. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 1095–1113.

- Samieiyeganeh, M.E.; Rahmat, R.W.; Khalid, F.B.; Kasmiran, K.B. An overview of deep learning techniques in echocardiography image segmentation. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2020, 98, 3561–3572.

- Wahlang, I.; Kumar Maji, A.; Saha, G.; Chakrabarti, P.; Jasinski, M.; Leonowicz, Z.; Jasinska, E.; Dimauro, G.; Bevilacqua, V.; Pecchia, L. Electronics Article. Electronics 2021, 10, 495.

- Muraki, R.; Teramoto Id, A.; Sugimoto, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Yamada, A.; Watanabe, E. Automated Detection Scheme for Acute Myocardial Infarction Using Convolutional Neural Network and Long Short-Term Memory. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264002.

- Roy, S.S.; Hsu, C.H.; Samaran, A.; Goyal, R.; Pande, A.; Balas, V.E. Vessels Segmentation in Angiograms Using Convolutional Neural Network: A Deep Learning Based Approach. CMES Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 136, 241–255.

- Liu, J.; Yuan, G.; Yang, C.; Song, H.; Luo, L. An Interpretable CNN for the Segmentation of the Left Ventricle in Cardiac MRI by Real-Time Visualization. CMES Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 135, 1571–1587.

- Tandon, A. Artificial Intelligence in Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. In Intelligence-Based Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery: Artificial Intelligence and Human Cognition in Cardiovascular Medicine; Academic Press: London, UK, 2024; pp. 201–209.

- Candemir, S.; White, R.D.; Demirer, M.; Gupta, V.; Bigelow, M.T.; Prevedello, L.M.; Erdal, B.S. Automated Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis Detection and Weakly Supervised Localization on Coronary CT Angiography with a Deep 3-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2020, 83, 101721.

- Singh, N.; Gunjan, V.K.; Shaik, F.; Roy, S. Detection of Cardio Vascular Abnormalities Using Gradient Descent Optimization and CNN. Health Technol. 2024, 14, 155–168.

- Banerjee, D.; Dey, S.; Pal, A. An SNN Based ECG Classifier for Wearable Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Workshop on Learning from Time Series for Health, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2 December 2022.

- Ullah, U.; García, A.; Jurado, O.; Diez Gonzalez, I.; Garcia-Zapirain, B. A Fully Connected Quantum Convolutional Neural Network for Classifying Ischemic Cardiopathy. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 134592–134605.

- Çınar, A.; Tuncer, S.A. Classification of Normal Sinus Rhythm, Abnormal Arrhythmia and Congestive Heart Failure ECG Signals Using LSTM and Hybrid CNN-SVM Deep Neural Networks. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2021, 24, 203–214.

- Fradi, M.; Khriji, L.; Machhout, M. Real-Time Arrhythmia Heart Disease Detection System Using CNN Architecture Based Various Optimizers-Networks. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 41711–41732.

- Rahul, J.; Sharma, L.D. Automatic Cardiac Arrhythmia Classification Based on Hybrid 1-D CNN and Bi-LSTM Model. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 42, 312–324.

- Ahmed, A.A.; Ali, W.; Abdullah, T.A.A.; Malebary, S.J.; Yao, Y.; Huang, X.; Ahmed, A.A.; Ali, W.; Abdullah, T.A.A.; Malebary, S.J. Citation: Classifying Cardiac Arrhythmia from ECG Signal Using 1D CNN Deep Learning Model. Mathematics 2023, 11, 562.

- Eltrass, A.S.; Tayel, M.B.; Ammar, A.I. A New Automated CNN Deep Learning Approach for Identification of ECG Congestive Heart Failure and Arrhythmia Using Constant-Q Non-Stationary Gabor Transform. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 65, 102326.

- Zheng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Hu, F.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Q.; Liang, Y. Electronics Article. Electronics 2020, 9, 121.

- Cheng, J.; Zou, Q.; Zhao, Y. ECG Signal Classification Based on Deep CNN and BiLSTM. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 365.

- Rawal, V.; Prajapati, P.; Darji, A. Hardware Implementation of 1D-CNN Architecture for ECG Arrhythmia Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 85, 104865.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. A CNN Model for Cardiac Arrhythmias Classification Based on Individual ECG Signals. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2022, 13, 548–557.

- Khozeimeh, F.; Sharifrazi, D.; Izadi, N.H.; Hassannataj Joloudari, J.; Shoeibi, A.; Alizadehsani, R.; Tartibi, M.; Hussain, S.; Sani, Z.A.; Khodatars, M.; et al. RF-CNN-F: Random Forest with Convolutional Neural Network Features for Coronary Artery Disease Diagnosis Based on Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17.

- Aslan, M.F.; Sabanci, K.; Durdu, A. A CNN-Based Novel Solution for Determining the Survival Status of Heart Failure Patients with Clinical Record Data: Numeric to Image. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102716.

- Yoon, T.; Kang, D. Bimodal CNN for Cardiovascular Disease Classification by Co-Training ECG Grayscale Images and Scalograms. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2937.

- Sun, L.; Shang, D.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Tian, F.; Liang, J.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wu, H.; et al. MSPAN: A Memristive Spike-Based Computing Engine With Adaptive Neuron for Edge Arrhythmia Detection. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 761127.

- Wang, J.; Zang, J.; Yao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, C. Multiclassification for Heart Sound Signals under Multiple Networks and Multi-View Feature. Measurement 2024, 225, 114022.

- Wang, L.-H.; Ding, L.-J.; Xie, C.-X.; Jiang, S.-Y.; Kuo, I.-C.; Wang, X.-K.; Gao, J.; Huang, P.-C.; Patricia, A.; Abu, A.R. Automated Classification Model With OTSU and CNN Method for Premature Ventricular Contraction Detection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 156581–156591.

- Jungiewicz, M.; Jastrzębski, P.; Wawryka, P.; Przystalski, K.; Sabatowski, K.; Bartuś, S. Vision Transformer in Stenosis Detection of Coronary Arteries. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 228, 120234.

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, G.; Wang, W.; Cao, S.; Dong, S.; Yu, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, K. TTN: Topological Transformer Network for Automated Coronary Artery Branch Labeling in Cardiac CT Angiography. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2023, 12, 129–139.

- Rao, S.; Li, Y.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Hassaine, A.; Canoy, D.; Cleland, J.; Lukasiewicz, T.; Salimi-Khorshidi, G.; Rahimi, K.; Shishir Rao, O. An Explainable Transformer-Based Deep Learning Model for the Prediction of Incident Heart Failure. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 2022, 26, 3362–3372.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. A Dense RNN for Sequential Four-Chamber View Left Ventricle Wall Segmentation and Cardiac State Estimation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 696227.

- Ding, C.; Wang, S.; Jin, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. A Novel Transformer-Based ECG Dimensionality Reduction Stacked Auto-Encoders for Arrhythmia Beat Detection. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 5897–5912.

- Ding, Y.; Xie, W.; Wong, K.K.L.; Liao, Z. DE-MRI Myocardial Fibrosis Segmentation and Classification Model Based on Multi-Scale Self-Supervision and Transformer. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 226, 107049.

- Hu, R.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L. A Transformer-Based Deep Neural Network for Arrhythmia Detection Using Continuous ECG Signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 144, 105325.

- Gaudilliere, P.L.; Sigurthorsdottir, H.; Aguet, C.; Van Zaen, J.; Lemay, M.; Delgado-Gonzalo, R. Generative Pre-Trained Transformer for Cardiac Abnormality Detection. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/mitdb/1.0.0/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Lecesne, E.; Simon, A.; Garreau, M.; Barone-Rochette, G.; Fouard, C. Segmentation of Cardiac Infarction in Delayed-Enhancement MRI Using Probability Map and Transformers-Based Neural Networks. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 242, 107841.

- Ahmadi, N.; Tsang, M.Y.; Gu, A.N.; Tsang, T.S.M.; Abolmaesumi, P. Transformer-Based Spatio-Temporal Analysis for Classification of Aortic Stenosis Severity from Echocardiography Cine Series. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 366–376.

- Han, T.; Ai, D.; Li, X.; Fan, J.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Coronary Artery Stenosis Detection via Proposal-Shifted Spatial-Temporal Transformer in X-Ray Angiography. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 153, 106546.

- Ning, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xi, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, C. CAC-EMVT: Efficient Coronary Artery Calcium Segmentation with Multi-Scale Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Houston, TX, USA, 9–12 December 2021; pp. 1462–1467.

- Deng, K.; Meng, Y.; Gao, D.; Bridge, J.; Shen, Y.; Lip, G.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y. TransBridge: A Lightweight Transformer for Left Ventricle Segmentation in Echocardiography. In Simplifying Medical Ultrasound; Noble, J.A., Aylward, S., Grimwood, A., Min, Z., Lee, S.-L., Hu, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 63–72.

- Alkhodari, M.; Kamarul Azman, S.; Hadjileontiadis, L.J.; Khandoker, A.H. Ensemble Transformer-Based Neural Networks Detect Heart Murmur in Phonocardiogram Recordings. In Proceedings of the 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC), Tampere, Finland, 4–7 September 2022.

- Meng, L.; Tan, W.; Ma, J.; Wang, R.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Y. Enhancing Dynamic ECG Heartbeat Classification with Lightweight Transformer Model. Artif. Intell. Med. 2022, 124, 102236.

- Chu, M.; Wu, P.; Li, G.; Yang, W.; Gutiérrez-Chico, J.L.; Tu, S. Advances in Diagnosis, Therapy, and Prognosis of Coronary Artery Disease Powered by Deep Learning Algorithms. JACC Asia 2023, 3, 1–14.

- Feng, Y.; Geng, S.; Chu, J.; Fu, Z.; Hong, S. Building and Training a Deep Spiking Neural Network for ECG Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 77, 103749.

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wong, W.F. Energy Efficient ECG Classification with Spiking Neural Network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 63, 102170.

- Kovács, P.; Samiee, K. Arrhythmia Detection Using Spiking Variable Projection Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC), Tampere, Finland, 4–7 September 2022; Volume 49.

- Singhal, S.; Kumar, M. GSMD-SRST: Group Sparse Mode Decomposition and Superlet Transform Based Technique for Multi-Level Classification of Cardiac Arrhythmia. IEEE Sens. J. 2024.

- Kiladze, M.R.; Lyakhova, U.A.; Lyakhov, P.A.; Nagornov, N.N.; Vahabi, M. Multimodal Neural Network for Recognition of Cardiac Arrhythmias Based on 12-Load Electrocardiogram Signals. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 133744–133754.

- Li, Z.; Calvet, L.E. Extraction of ECG Features with Spiking Neurons for Decreased Power Consumption in Embedded Devices Extraction of ECG Features with Spiking Neurons for Decreased Power Consumption in Embedded Devices Extraction of ECG Features with Spiking Neurons for Decreased Power Consumption in Embedded Devices. In Proceedings of the 2023 19th International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Methods and Applications to Circuit Design (SMACD), Funchal, Portugal, 3–5 July 2023.

- Revathi, T.K.; Sathiyabhama, B.; Sankar, S. Diagnosing Cardio Vascular Disease (CVD) Using Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) in Retinal Fundus Images. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 2563–2572. Available online: http://annalsofrscb.ro (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Chen, J.; Yang, G.; Khan, H.R.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Mohiaddin, R.H.; Wong, T.; Firmin, D.N.; Keegan, J. JAS-GAN: Generative Adversarial Network Based Joint Atrium and Scar Segmentations on Unbalanced Atrial Targets. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 2021, 26, 103–114.

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; Guo, X.; Ren, Y. Comparative Analysis of U-Net and TLMDB GAN for the Cardiovascular Segmentation of the Ventricles in the Heart. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 215, 106614.

- Decourt, C.; Duong, L. Semi-Supervised Generative Adversarial Networks for the Segmentation of the Left Ventricle in Pediatric MRI. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 123, 103884.

- Diller, G.P.; Vahle, J.; Radke, R.; Vidal, M.L.B.; Fischer, A.J.; Bauer, U.M.M.; Sarikouch, S.; Berger, F.; Beerbaum, P.; Baumgartner, H.; et al. Utility of Deep Learning Networks for the Generation of Artificial Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Images in Congenital Heart Disease. BMC Med. Imaging 2020, 20, 113.

- Rizwan, I.; Haque, I.; Neubert, J. Deep Learning Approaches to Biomedical Image Segmentation. Inf. Med. Unlocked 2020, 18, 100297.

- Van Lieshout, F.E.; Klein, R.C.; Kolk, M.Z.; Van Geijtenbeek, K.; Vos, R.; Ruiperez-Campillo, S.; Feng, R.; Deb, B.; Ganesan, P.; Knops, R.; et al. Deep Learning for Ventricular Arrhythmia Prediction Using Fibrosis Segmentations on Cardiac MRI Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 Computing in Cardiology (CinC), Tampere, Finland, 4–7 September 2022.

- Liu, X.; He, L.; Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X. A Neural Network for High-Precise and Well-Interpretable Electrocardiogram Classification. bioRxiv 2023.

- Lu, P.; Bai, W.; Rueckert, D.; Noble, J.A. Modelling Cardiac Motion via Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks to Boost the Diagnosis of Heart Conditions. In Statistical Atlases and Computational Models of the Heart; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020.

- Yang, H.; Zhen, X.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hua, X.-S. CPR-GCN: Conditional Partial-Residual Graph Convolutional Network in Automated Anatomical Labeling of Coronary Arteries. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020.

- Huang, F.; Lian, J.; Ng, K.-S.; Shih, K.; Vardhanabhuti, V.; Huang, F.; Lian, J.; Ng, K.-S.; Shih, K.; Vardhanabhuti, V. Citation: Predicting CT-Based Coronary Artery Disease Using Vascular Biomarkers Derived from Fundus Photographs with a Graph Convolutional Neural Network. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1390.

- Gao, R.; Hou, Z.; Li, J.; Han, H.; Lu, B.; Zhou, S.K. Joint Coronary Centerline Extraction And Lumen Segmentation From Ccta Using Cnntracker And Vascular Graph Convolutional Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Nice, France, 13–16 April 2021; pp. 1897–1901.

- Chakravarty, A.; Sarkar, T.; Ghosh, N.; Sethuraman, R.; Sheet, D. Learning Decision Ensemble Using a Graph Neural Network for Comorbidity Aware Chest Radiograph Screening. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 1234–1237.

- Reddy, G.T.; Praveen, M.; Reddy, K.; Lakshmanna, K.; Rajput, D.S.; Kaluri, R.; Gautam, S. Hybrid Genetic Algorithm and a Fuzzy Logic Classifier for Heart Disease Diagnosis. Evol. Intell. 2020, 13, 185–196.

- Priyanka; Baranwal, N.; Singh, K.N.; Singh, A.K. YOLO-Based ROI Selection for Joint Encryption and Compression of Medical Images with Reconstruction through Super-Resolution Network. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 150, 1–9.

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02696.

- Zhuang, Z.; Jin, P.; Joseph Raj, A.N.; Yuan, Y.; Zhuang, S. Automatic Segmentation of Left Ventricle in Echocardiography Based on YOLOv3 Model to Achieve Constraint and Positioning. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 3772129.

- Alamelu, V.; Thilagamani, S. Lion Based Butterfly Optimization with Improved YOLO-v4 for Heart Disease Prediction Using IoMT. Inf. Technol. Control 2022, 51, 692–703.

- Smirnov, D.; Pikunov, A.; Syunyaev, R.; Deviatiiarov, R.; Gusev, O.; Aras, K.; Gams, A.; Koppel, A.; Efimov, I.R. Correction: Genetic Algorithm-Based Personalized Models of Human Cardiac Action Potential. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231695.

- Kanwal, S.; Rashid, J.; Nisar, M.W.; Kim, J.; Hussain, A. An Effective Classification Algorithm for Heart Disease Prediction with Genetic Algorithm for Feature Selection. In Proceedings of the 2021 Mohammad Ali Jinnah University International Conference on Computing (MAJICC), Karachi, Pakistan, 15–17 July 2021.

- Alizadehsani, R.; Roshanzamir, M.; Abdar, M.; Beykikhoshk, A.; Khosravi, A.; Nahavandi, S.; Plawiak, P.; Tan, R.S.; Acharya, U.R. Hybrid Genetic-Discretized Algorithm to Handle Data Uncertainty in Diagnosing Stenosis of Coronary Arteries. Expert Syst. 2020, 39, e12573.

- Badano, L.P.; Keller, D.M.; Muraru, D.; Torlasco, C.; Parati, G. Artificial Intelligence and Cardiovascular Imaging: A Win-Win Combination. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2020, 24, 214–223.

- Souza Filho, E.M.; Fernandes, F.A.; Pereira, N.C.A.; Mesquita, C.T.; Gismondi, R.A. Ethics, Artificial Intelligence and Cardiology. Arq. Bras. De Cardiol. 2020, 115, 579–583.

- Mathur, P.; Srivastava, S.; Xu, X.; Mehta, J.L. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Cardiovascular Disease. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2020, 14, 1179546820927404.

- Miller, D.D. Machine Intelligence in Cardiovascular Medicine. Cardiol. Rev. 2020, 28, 53–64.

- Swathy, M.; Saruladha, K. A Comparative Study of Classification and Prediction of Cardio-Vascular Diseases (CVD) Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques. ICT Express 2021, 8, 109–116.

- Gao, Z.; Wang, L.; Soroushmehr, R.; Wood, A.; Gryak, J.; Nallamothu, B.; Najarian, K. Vessel Segmentation for X-Ray Coronary Angiography Using Ensemble Methods with Deep Learning and Filter-Based Features. BMC Med. Imaging 2022, 22, 10.

- Galea, R.R.; Diosan, L.; Andreica, A.; Popa, L.; Manole, S.; Bálint, Z. Region-of-Interest-Based Cardiac Image Segmentation with Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1965.

- Tandon, A.; Mohan, N.; Jensen, C.; Burkhardt, B.E.U.; Gooty, V.; Castellanos, D.A.; McKenzie, P.L.; Zahr, R.A.; Bhattaru, A.; Abdulkarim, M.; et al. Retraining Convolutional Neural Networks for Specialized Cardiovascular Imaging Tasks: Lessons from Tetralogy of Fallot. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2021, 42, 578–589.

- Stough, J.V.; Raghunath, S.; Zhang, X.; Pfeifer, J.M.; Fornwalt, B.K.; Haggerty, C.M. Left Ventricular and Atrial Segmentation of 2D Echocardiography with Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2020: Image Processing, Houston, TX, USA, 10 March 2020.

- Sander, J.; de Vos, B.D.; Išgum, I. Automatic Segmentation with Detection of Local Segmentation Failures in Cardiac MRI. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21769.

- Lin, A.; Chen, B.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G. DS-TransUNet: Dual Swin Transformer U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 4005615.

- Koresh, H.J.D.; Chacko, S.; Periyanayagi, M. A Modified Capsule Network Algorithm for Oct Corneal Image Segmentation. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2021, 143, 104–112.

- Khan, M.Z.; Gajendran, M.K.; Lee, Y.; Khan, M.A. Deep Neural Architectures for Medical Image Semantic Segmentation: Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 83002–83024.

- Lu, X.H.; Liu, A.; Fuh, S.C.; Lian, Y.; Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; Marelli, A.; Li, Y. Recurrent Disease Progression Networks for Modelling Risk Trajectory of Heart Failure. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245177.

- Fu, Q.; Dong, H. An Ensemble Unsupervised Spiking Neural Network for Objective Recognition. Neurocomputing 2021, 419, 47–58.

- Rana, A.; Kim, K.K. A Novel Spiking Neural Network for ECG Signal Classification. J. Sens. Sci. Technol. 2021, 30, 20–24.

- Kim, Y.; Panda, P. Visual Explanations from Spiking Neural Networks Using Inter-Spike Intervals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19037.

- Kazeminia, S.; Baur, C.; Kuijper, A.; van Ginneken, B.; Navab, N.; Albarqouni, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A. GANs for Medical Image Analysis. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 109, 101938.

- Olender, M.L.; Nezami, F.R.; Athanasiou, L.S.; De La Torre Hernández, J.M.; Edelman, E.R. Translational Challenges for Synthetic Imaging in Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2021, 2, 559–560.

- Wieneke, H.; Voigt, I. Principles of Artificial Intelligence and Its Application in Cardiovascular Medicine. Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 47, e24148.

- Hasan Rafi, T.; Shubair, R.M.; Farhan, F.; Hoque, Z.; Mohd Quayyum, F. Recent Advances in Computer-Aided Medical Diagnosis Using Machine Learning Algorithms with Optimization Techniques. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 137847–137868.

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. Available online: https://github.com/facebookresearch/detr (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Huang, J.; Ren, L.; Feng, L.; Yang, F.; Yang, L.; Yan, K. AI Empowered Virtual Reality Integrated Systems for Sleep Stage Classification and Quality Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Neural. Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 1494–1503.

- Jannatul Ferdous, G.; Akhter Sathi, K.; Hossain, A.; Moshiul Hoque, M.; Member, S.; Ali Akber Dewan, M. LCDEiT: A Linear Complexity Data-Efficient Image Transformer for MRI Brain Tumor Classification. IEEE Access 2017, 11, 20337–20350.

- Beer, K.; Bondarenko, D.; Farrelly, T.; Osborne, T.J.; Salzmann, R.; Scheiermann, D.; Wolf, R. Training Deep Quantum Neural Networks. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 808.

- Landman, J.; Mathur, N.; Li, Y.Y.; Strahm, M.; Kazdaghli, S.; Prakash, A.; Kerenidis, I. Quantum Methods for Neural Networks and Application to Medical Image Classification. Quantum 2022, 6, 881.

- Shahwar, T.; Zafar, J.; Almogren, A.; Zafar, H.; Rehman, A.U.; Shafiq, M.; Hamam, H. Automated Detection of Alzheimer’s via Hybrid Classical Quantum Neural Networks. Electronics 2022, 11, 721.

- Ovalle-Magallanes, E.; Avina-Cervantes, J.G.; Cruz-Aceves, I.; Ruiz-Pinales, J. Hybrid Classical–Quantum Convolutional Neural Network for Stenosis Detection in X-Ray Coronary Angiography. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 189, 116112.

- Kumar, A.; Choudhary, A.; Tiwari, A.; James, C.; Kumar, H.; Kumar Arora, P.; Akhtar Khan, S. An Investigation on Wear Characteristics of Additive Manufacturing Materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 3654–3660.

- Belli, C.; Sagingalieva, A.; Kordzanganeh, M.; Kenbayev, N.; Kosichkina, D.; Tomashuk, T.; Melnikov, A. Hybrid Quantum Neural Network For Drug Response Prediction. Cancers 2023, 15, 2705.

- Pregowska, A.; Perkins, M. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Technology and Ethical Risk. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4643763 (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Rastogi, D.; Johri, P.; Tiwari, V.; Elngar, A.A. Multi-Class Classification of Brain Tumour Magnetic Resonance Images Using Multi-Branch Network with Inception Block and Five-Fold Cross Validation Deep Learning Framework. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 88, 105602.