Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Deming Tan.

Photocatalytic synthesis of H2O2 has emerged as a compelling alternative, offering the prospect of harnessing solar energy directly to drive chemical reactions, thereby circumventing the need for energy-intensive processes and deleterious chemicals.

- covalent organic framework

- H2O2 photosynthesis

- photosynthesis

1. Introduction

The quest for sustainable and clean energy sources has become a paramount concern in the face of escalating global energy demands and the pressing challenges of climate change. Solar energy, being abundant and renewable, stands out as a promising candidate to address these challenges. Efficiently harnessing the vast potential of solar energy not only offers a solution to the impending energy crisis but also holds the promise of reducing the carbon footprint associated with conventional fossil fuels. Photocatalysis is a process that uses light to drive chemical reactions and has emerged as an important technology [1,2,3,4,5,6][1][2][3][4][5][6]. By converting solar energy into chemical energy, photocatalysis offers a dual advantage [4,7][4][7]: it provides an avenue for sustainable energy storage and paves the way for the synthesis of valuable chemicals, including H2, CO, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

Among various chemicals synthesized by photosynthesis, H2O2 has attracted significant attention [2,8,9,10][2][8][9][10]. H2O2 is valuable for its multifaceted applications and environmentally amicable nature, and has become an indispensable chemical field like industrial processes, environmental remediation, and healthcare and medical applications [11,12,13,14][11][12][13][14]. Its ability to decompose into water and oxygen underpins its appeal as an eco-friendly oxidant, minimizing the risk of generating secondary pollutants. The conventional anthraquinone oxidation process [15], which has been the industrial applicable for H2O2 production, is increasingly being scrutinized for its inherent drawbacks. These include not only the substantial energy consumption and the utilization of hazardous substrates but also the generation of significant amounts of waste, which poses considerable environmental and economic challenges. In light of these limitations, the researchers have pivoted towards seeking alternative, sustainable, and cleaner methods for H2O2 production, with a particular emphasis on minimizing environmental repercussions. Photocatalytic synthesis of H2O2 has emerged as a compelling alternative, offering the prospect of harnessing solar energy directly to drive chemical reactions, thereby circumventing the need for energy-intensive processes and deleterious chemicals [16,17][16][17]. This approach not only aligns with the global shift towards sustainable energy but also presents a pathway for the localized, on-demand production of H2O2, reducing the need for storage and transportation.

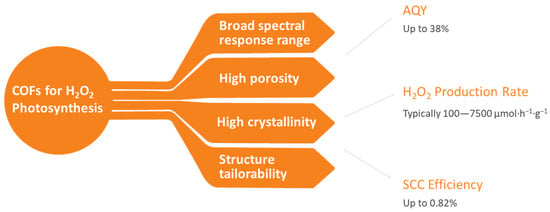

In the realm of photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis, the role of catalysts is paramount, dictating the efficiency, selectivity, and stability of the photocatalytic processes. Conventional photocatalysts are predominantly based on precious metals such as platinum [18], palladium [19], and gold [20[20][21],21], demonstrating commendable performance in facilitating the production of H2O2. However, the deployment of these noble metal-based catalysts is significantly hampered by their scarcity in the Earth’s crust, which intrinsically leads to high costs and poses sustainability concerns, especially in the context of large-scale applications and global accessibility. Consequently, the exploration of alternative non-metal-based photocatalysts has become a focal point in contemporary research, aiming to circumvent the limitations associated with noble-metal catalysts. Metal-free photocatalysts, particularly those based on linear polymers [22], polymeric carbon nitride (PCN) [23[23][24],24], polymer resins [25], supramolecular coordination [26[26][27],27], and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) [2[2][28][29],28,29], have emerged as promising candidates, offering the advantages of abundance and low cost under photocatalytic conditions. Among these, COFs, with their intrinsic porosity, tunable structures, and the ability to incorporate a myriad of organic functional groups (Figure 1), have garnered substantial attention since 2020 [30,31,32][30][31][32].

Figure 1.

The advantages of COFs for the photosynthesis of H

2

O

2

.

COFs are typically a class of porous polymers formed by organic building blocks connected through covalent bonds. They were first synthesized by Yaghi et al. under solvothermal conditions through the self-condensation of phenyl diboronic acid (PDBA) and the co-condensation of PDBA with hexahydroxytriphenylene (HHTP) [33]. This work opened the door to COF research. Subsequently, various methods for synthesizing COFs have been reported, including solvothermal [34[34][35][36][37][38],35,36,37,38], microwave [39[39][40][41],40,41], ionothermal [42[42][43][44],43,44], and mechanochemical methods [45,46][45][46] for powder synthesis, and interfacial methods [47,48,49][47][48][49] for thin-film synthesis. At the same time, a wide variety of organic building blocks and linkages have been reported. To date, reported linkages include boroxine [50], boronate-ester [51[51][52][53],52,53], imine [54[54][55][56][57],55,56,57], hydrazone [58[58][59],59], squaraine [60[60][61][62],61,62], azine [63,64,65][63][64][65], imide [66,67][66][67], C=C [68[68][69][70][71],69,70,71], 1,4-dioxin linkage [72,73][72][73], among others. The COFs synthesized by these methods have shown great potential in applications such as sensing [74[74][75][76],75,76], catalysis [5[5][77][78][79],77,78,79], energy storage and conversion, [6,80,81,82,83][6][80][81][82][83] organic electronic devices [84,85[84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92],86,87,88,89,90,91,92], etc. [6,80,81,82,83,93,94,95,96][6][80][81][82][83][93][94][95][96].

2. Principles of Photocatalytic H2O2 Generation

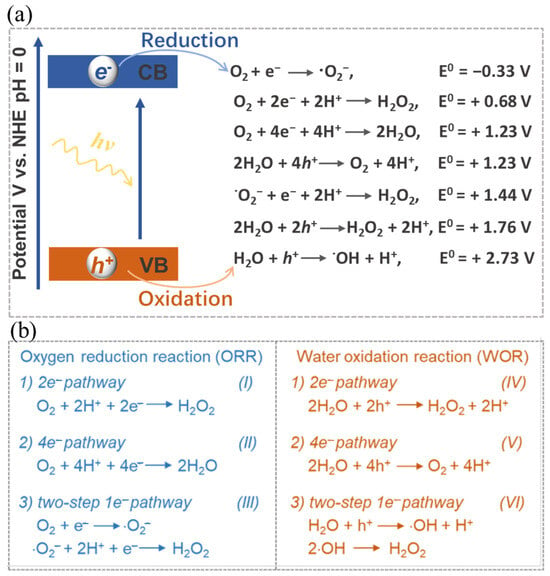

Equation (1) illustrates the full process of photocatalytic synthesis of H2O2. This procedure encompasses two distinct half-reactions, namely the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) (Equations (2) and (3)) and the water oxidation reaction (WOR) (Equation (4)). In response to the impetus of photons, the electrons within the catalyst undergo a transition from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), thus giving rise to the emergence of photo-excited h+ and e− species. The subsequent migration of these charges to the catalyst’s surface facilitates their active participation in a cascading series of reduction-oxidation reactions (Figure 2a), thereby selectively yielding H2O2.

Figure 2. (a) Schematic illustration and (b) Corresponding energy diagrams of the oxygen reduction and water oxidation involved in H2O2 photosynthesis. Reproduced with permission [1].

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the solar-to-chemical energy conversion efficiency (SCC) in the context of photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis remains relatively low at present, seldom surpassing 1% [97]. This efficiency discrepancy is quite pronounced when compared to the performance observed in photocatalytic hydrogen production from water [98,99][98][99]. Several factors contribute to this relatively low efficiency, including limited light absorption, a propensity for charge recombination, and challenges in achieving desirable selectivity towards H2O2 [97,100,101][97][100][101]. Particularly, achieving selectivity towards H2O2 presents a significant hurdle (Figure 2). The WOR process commonly tends to favor O2 production via the 4e− pathway rather than H2O2 production through the 2e− pathway [17]. Additionally, side reactions and H2O2 decomposition also impact both the yield and selectivity [102,103][102][103]. Through the desirable optimization of catalyst structures and reaction conditions, significant enhancements can be achieved in terms of the yield and selectivity of photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the solar-to-chemical energy conversion efficiency (SCC) in the context of photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis remains relatively low at present, seldom surpassing 1% [97]. This efficiency discrepancy is quite pronounced when compared to the performance observed in photocatalytic hydrogen production from water [98,99][98][99]. Several factors contribute to this relatively low efficiency, including limited light absorption, a propensity for charge recombination, and challenges in achieving desirable selectivity towards H2O2 [97,100,101][97][100][101]. Particularly, achieving selectivity towards H2O2 presents a significant hurdle (Figure 2). The WOR process commonly tends to favor O2 production via the 4e− pathway rather than H2O2 production through the 2e− pathway [17]. Additionally, side reactions and H2O2 decomposition also impact both the yield and selectivity [102,103][102][103]. Through the desirable optimization of catalyst structures and reaction conditions, significant enhancements can be achieved in terms of the yield and selectivity of photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis.

References

- Yong, Z.; Ma, T. Solar-to-H2O2 Catalyzed by Covalent Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 135, e202308980.

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Miao, J.; Wen, X.; Chen, C.; Zhou, B.; Long, M. Keto-enamine-based covalent organic framework with controllable anthraquinone moieties for superior H2O2 photosynthesis from O2 and water. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143085.

- Yang, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, X.; Kong, A. Weakly Hydrophilic Imine-Linked Covalent Benzene-Acetylene Frameworks for Photocatalytic H2O2 Production in the Two-Phase System. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 8066–8075.

- Wu, M.; Shan, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, G. Three-dimensional covalent organic framework with tty topology for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140121.

- Li, J.; Gao, S.Y.; Liu, J.; Ye, S.; Feng, Y.; Si, D.H.; Cao, R. Use in Photoredox Catalysis of Stable Donor–Acceptor Covalent Organic Frameworks and Membrane Strategy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2305735.

- Chatterjee, A.; Sun, J.; Rawat, K.S.; Van Speybroeck, V.; Van Der Voort, P. Exploring the Charge Storage Dynamics in Donor–Acceptor Covalent Organic Frameworks Based Supercapacitors by Employing Ionic Liquid Electrolyte. Small 2023, 19, 2303189.

- Kofuji, Y.; Ohkita, S.; Shiraishi, Y.; Sakamoto, H.; Tanaka, S.; Ichikawa, S.; Hirai, T. Graphitic Carbon Nitride Doped with Biphenyl Diimide: Efficient Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Peroxide Production from Water and Molecular Oxygen by Sunlight. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7021–7029.

- Yu, F.Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Tan, H.Q.; Li, Y.G.; Kang, Z.H. Versatile Photoelectrocatalysis Strategy Raising Up the Green Production of Hydrogen Peroxide. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2300119.

- Tian, Q.; Zeng, X.K.; Zhao, C.; Jing, L.Y.; Zhang, X.W.; Liu, J. Exceptional Photocatalytic Hydrogen Peroxide Production from Sandwich-Structured Graphene Interlayered Phenolic Resins Nanosheets with Mesoporous Channels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213173.

- Shao, C.; He, Q.; Zhang, M.; Jia, L.; Ji, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, Y. A covalent organic framework inspired by C3N4 for photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide with high quantum efficiency. Chin. J. Catal. 2023, 46, 28–35.

- Jones, C.W. Applications of Hydrogen Peroxide and Derivatives; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Volume 2.

- Targhan, H.; Evans, P.; Bahrami, K.J. A review of the role of hydrogen peroxide in organic transformations. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 104, 295–332.

- Urban, M.V.; Rath, T.; Radtke, C. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2): A review of its use in surgery. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2017, 169, 222–225.

- Ciriminna, R.; Albanese, L.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Hydrogen peroxide: A key chemical for today’s sustainable development. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 3374–3381.

- Campos-Martin, J.M.; Blanco-Brieva, G.; Fierro, J.L. Hydrogen peroxide synthesis: An outlook beyond the anthraquinone process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6962–6984.

- Yu, W.; Hu, C.; Bai, L.; Tian, N.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H. Photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide evolution: What is the most effective strategy? Nano Energy 2022, 104, 107906.

- Zeng, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X. Photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide evolution: What is the most effective strategy? Green Chem. 2021, 23, 1466–1494.

- Liu, D.; Shen, J.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Long, J.; Lin, H.; Wang, X. Metallic Pt and PtO2 Dual-Cocatalyst-Loaded Binary Composite RGO-CNx for the Photocatalytic Production of Hydrogen and Hydrogen Peroxide. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 6380–6389.

- Chu, C.; Huang, D.; Zhu, Q.; Stavitski, E.; Spies, J.A.; Pan, Z.; Mao, J.; Xin, H.L.; Schmuttenmaer, C.A.; Hu, S. Electronic tuning of metal nanoparticles for highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. ACS Catal. 2018, 9, 626–631.

- Hirakawa, H.; Shiota, S.; Shiraishi, Y.; Sakamoto, H.; Ichikawa, S.; Hirai, T. Au Nanoparticles Supported on BiVO4: Effective Inorganic Photocatalysts for H2O2 Production from Water and O2 under Visible Light. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4976–4982.

- Zuo, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Song, H.; Zong, P.; Hou, W.; Li, B.; Guo, Z.; Meng, X.; Du, Y. Finely dispersed Au nanoparticles on graphitic carbon nitride as highly active photocatalyst for hydrogen peroxide production. Catal. Commun. 2019, 123, 69–72.

- Liu, L.; Gao, M.Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Cooper, A.I. Linear Conjugated Polymers for Solar-Driven Hydrogen Peroxide Production: The Importance of Catalyst Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 19287–19293.

- Shiraishi, Y.; Kanazawa, S.; Sugano, Y.; Tsukamoto, D.; Sakamoto, H.; Ichikawa, S.; Hirai, T. Highly selective production of hydrogen peroxide on graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) photocatalyst activated by visible light. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 774–780.

- Liu, B.; Du, J.; Ke, G.; Jia, B.; Huang, Y.; He, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, Z. Boosting O2 Reduction and H2O Dehydrogenation Kinetics: Surface N-Hydroxymethylation of g-C3N4 Photocatalysts for the Efficient Production of H2O2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2111125.

- Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhao, C.; Pi, Y.; Li, X.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, J.; Wu, L.; Liu, J. Ambient Preparation of Benzoxazine-based Phenolic Resins Enables Long-term Sustainable Photosynthesis of Hydrogen Peroxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202302829.

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, S.; Sun, L.X.; Xing, Y.H.; Bai, F.Y. Synthesis and structure of a 3D supramolecular layered Bi-MOF and its application in photocatalytic degradation of dyes. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1270, 133895.

- Ham, R.; Nielsen, C.J.; Pullen, S.; Reek, J.N. Supramolecular Coordination Cages for Artificial Photosynthesis and Synthetic Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5225.

- Sun, J.; Sekhar Jena, H.; Krishnaraj, C.; Singh Rawat, K.; Abednatanzi, S.; Chakraborty, J.; Laemont, A.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.Y.; et al. Pyrene-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Peroxide Production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216719.

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, C.; Bian, G.; Xu, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lou, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Y. H2O2 generation from O2 and H2O on a near-infrared absorbing porphyrin supramolecular photocatalyst. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 361–371.

- Gong, Y.-N.; Guan, X.; Jiang, H.-L. Covalent organic frameworks for photocatalysis: Synthesis, structural features, fundamentals and performance. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 475, 214889.

- Tan, F.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; Dong, X.; Yang, J.; Ou, Z.; Qi, H.; Liu, W.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Aqueous Synthesis of Covalent Organic Frameworks as Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Peroxide Production. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 3751–3761.

- Li, H.; Wang, L.; Yu, G. Covalent organic frameworks: Design, synthesis, and performance for photocatalytic applications. Nano Today 2021, 40, 101247.

- Côté, A.P.; Benin, A.I.; Ockwig, N.W.; O’Keeffe, M.; Matzger, A.J.; Yaghi, O.M. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 2005, 310, 1166–1170.

- Huang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Liu, X. Solvothermal synthesis of microporous, crystalline covalent organic framework nanofibers and their colorimetric nanohybrid structures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 8845–8849.

- Chen, X.; Huang, N.; Gao, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, F.; Jiang, D. Towards covalent organic frameworks with predesignable and aligned open docking sites. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6161–6163.

- Xu, L.; Ding, S.-Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Q.-Y. Highly crystalline covalent organic frameworks from flexible building blocks. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4706–4709.

- Khalil, S.; Meyer, M.D.; Alazmi, A.; Samani, M.H.; Huang, P.-C.; Barnes, M.; Marciel, A.B.; Verduzco, R. Enabling solution processable COFs through suppression of precipitation during solvothermal synthesis. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 20964–20974.

- Xiong, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chu, J.; Zhang, R.; Gong, M.; Wu, B.J. Solvothermal synthesis of triphenylamine-based covalent organic framework nanofibers with excellent cycle stability for supercapacitor electrodes. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51510.

- Campbell, N.L.; Clowes, R.; Ritchie, L.K.; Cooper, A.I. Rapid microwave synthesis and purification of porous covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 204–206.

- Ren, S.; Bojdys, M.J.; Dawson, R.; Laybourn, A.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Adams, D.J.; Cooper, A.I. Porous, fluorescent, covalent triazine-based frameworks via room-temperature and microwave-assisted synthesis. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2357–2361.

- Wei, H.; Chai, S.; Hu, N.; Yang, Z.; Wei, L.; Wang, L. The microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis of a crystalline two-dimensional covalent organic framework with high CO2 capacity. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12178–12181.

- Kuhn, P.; Antonietti, M.; Thomas, A. Porous, covalent triazine-based frameworks prepared by ionothermal synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3450–3453.

- Bojdys, M.J.; Jeromenok, J.; Thomas, A.; Antonietti, M. Rational extension of the family of layered, covalent, triazine-based frameworks with regular porosity. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2202–2205.

- Guan, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Yusran, Y.; Xue, M.; Fang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Valtchev, V.; Qiu, S. Fast, ambient temperature and pressure ionothermal synthesis of three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4494–4498.

- Chandra, S.; Kandambeth, S.; Biswal, B.P.; Lukose, B.; Kunjir, S.M.; Chaudhary, M.; Babarao, R.; Heine, T.; Banerjee, R. Chemically stable multilayered covalent organic nanosheets from covalent organic frameworks via mechanical delamination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17853–17861.

- Shinde, D.B.; Aiyappa, H.B.; Bhadra, M.; Biswal, B.P.; Wadge, P.; Kandambeth, S.; Garai, B.; Kundu, T.; Kurungot, S.; Banerjee, R.J. A mechanochemically synthesized covalent organic framework as a proton-conducting solid electrolyte. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 2682–2690.

- Dey, K.; Pal, M.; Rout, K.C.; Kunjattu, H.S.; Das, A.; Mukherjee, R.; Kharul, U.K.; Banerjee, R. Selective molecular separation by interfacially crystallized covalent organic framework thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13083–13091.

- Hao, Q.; Zhao, C.; Sun, B.; Lu, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Wan, L.-J.; Wang, D. Confined synthesis of two-dimensional covalent organic framework thin films within superspreading water layer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12152–12158.

- Zhou, D.; Tan, X.; Wu, H.; Tian, L.; Li, M. Synthesis of C−C Bonded Two-Dimensional Conjugated Covalent Organic Framework Films by Suzuki Polymerization on a Liquid–Liquid Interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1376.

- Wan, S.; Guo, J.; Kim, J.; Ihee, H.; Jiang, D. A photoconductive covalent organic framework: Self-condensed arene cubes composed of eclipsed 2D polypyrene sheets for photocurrent generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5439–5442.

- Spitler, E.L.; Dichtel, W.R. Lewis acid-catalysed formation of two-dimensional phthalocyanine covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 672–677.

- Ma, H.; Ren, H.; Meng, S.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, H.; Sun, F.; Zhu, G. A 3D microporous covalent organic framework with exceedingly high C3H8/CH4 and C2 hydrocarbon/CH4 selectivity. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 9773–9775.

- Dalapati, S.; Jin, E.; Addicoat, M.; Heine, T.; Jiang, D. Highly emissive covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5797–5800.

- Vitaku, E.; Dichtel, W.R. Synthesis of 2D imine-linked covalent organic frameworks through formal transimination reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12911–12914.

- Waller, P.J.; AlFaraj, Y.S.; Diercks, C.S.; Jarenwattananon, N.N.; Yaghi, O.M. Conversion of imine to oxazole and thiazole linkages in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9099–9103.

- Cusin, L.; Peng, H.; Ciesielski, A.; Samori, P. Chemical Conversion and Locking of the Imine Linkage: Enhancing the Functionality of Covalent Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14236–14250.

- Qian, C.; Feng, L.; Teo, W.L.; Liu, J.; Zhou, W.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y. Imine and imine-derived linkages in two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 881–898.

- Zhang, Y.; Farrants, H.; Li, X. Adding a Functional Handle to Nature′ s Building Blocks: The Asymmetric Synthesis of β-Hydroxy-α-Amino Acids. Chem. Asian J. 2014, 9, 1752–1764.

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Feng, X.; Xia, H.; Mu, Y.; Liu, X. Covalent organic frameworks as pH responsive signaling scaffolds. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 11088–11091.

- Nagai, A.; Chen, X.; Feng, X.; Ding, X.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, D. A squaraine-linked mesoporous covalent organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 125, 3858–3862.

- Ding, N.; Zhou, T.; Weng, W.; Lin, Z.; Liu, S.; Maitarad, P.; Wang, C.; Guo, J. Multivariate Synthetic Strategy for Improving Crystallinity of Zwitterionic Squaraine-Linked Covalent Organic Frameworks with Enhanced Photothermal Performance. Small 2022, 18, 2201275.

- Ben, H.; Yan, G.; Liu, H.; Ling, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Local spatial polarization induced efficient charge separation of squaraine-linked COF for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2104519.

- Li, Z.; Zhi, Y.; Feng, X.; Ding, X.; Zou, Y.; Liu, X.; Mu, Y. An azine-linked covalent organic framework: Synthesis, characterization and efficient gas storage. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 12079–12084.

- Alahakoon, S.B.; Thompson, C.M.; Nguyen, A.X.; Occhialini, G.; McCandless, G.T.; Smaldone, R.A. An azine-linked hexaphenylbenzene based covalent organic framework. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 2843–2845.

- Yu, S.Y.; Mahmood, J.; Noh, H.J.; Seo, J.M.; Jung, S.M.; Shin, S.H.; Im, Y.K.; Jeon, I.Y.; Baek, J.B. Direct synthesis of a covalent triazine-based framework from aromatic amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8438–8442.

- Fang, Q.; Zhuang, Z.; Gu, S.; Kaspar, R.B.; Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Qiu, S.; Yan, Y. Designed synthesis of large-pore crystalline polyimide covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4503.

- Fang, Q.; Wang, J.; Gu, S.; Kaspar, R.B.; Zhuang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Guo, H.; Qiu, S.; Yan, Y. 3D porous crystalline polyimide covalent organic frameworks for drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8352–8355.

- Zhuang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, F.; Cao, Y.; Liu, F.; Bi, S.; Feng, X. A two-dimensional conjugated polymer framework with fully sp 2-bonded carbon skeleton. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 4176–4181.

- Jin, E.; Asada, M.; Xu, Q.; Dalapati, S.; Addicoat, M.A.; Brady, M.A.; Xu, H.; Nakamura, T.; Heine, T.; Chen, Q. Two-dimensional sp2 carbon–conjugated covalent organic frameworks. Science 2017, 357, 673–676.

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, Q.; Hu, F.; Wang, R.; Li, P.; Huang, X.; Li, Z. Fully conjugated two-dimensional sp2-carbon covalent organic frameworks as artificial photosystem I with high efficiency. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5376–5381.

- Lyu, H.; Diercks, C.S.; Zhu, C.; Yaghi, O.M. Porous crystalline olefin-linked covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6848–6852.

- Zhang, B.; Wei, M.; Mao, H.; Pei, X.; Alshmimri, S.A.; Reimer, J.A.; Yaghi, O.M. Crystalline dioxin-linked covalent organic frameworks from irreversible reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12715–12719.

- Guan, X.; Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Xue, M.; Fang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Valtchev, V.; Qiu, S. Chemically stable polyarylether-based covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 587–594.

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Yan, Y.; Xia, F.; Huang, A.; Xian, Y. Highly fluorescent polyimide covalent organic nanosheets as sensing probes for the detection of 2, 4, 6-trinitrophenol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13415–13421.

- Das, G.; Garai, B.; Prakasam, T.; Benyettou, F.; Varghese, S.; Sharma, S.K.; Gándara, F.; Pasricha, R.; Baias, M.; Jagannathan, R. Fluorescence turn on amine detection in a cationic covalent organic framework. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3904.

- Zhang, J.-L.; Yao, L.-Y.; Yang, Y.; Liang, W.-B.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, D.-R. Conductive covalent organic frameworks with conductivity-and pre-reduction-enhanced electrochemiluminescence for ultrasensitive biosensor construction. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 3685–3692.

- Kurisingal, J.F.; Kim, H.; Choe, J.H.; Hong, C.S. Covalent organic framework-based catalysts for efficient CO2 utilization reactions. Coord. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 473, 214835.

- Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Shang, S.; Gao, W.; Du, C.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, J. Near-Equilibrium Growth of Chemically Stable Covalent Organic Framework/Graphene Oxide Hybrid Materials for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202113067.

- Liu, S.; Wang, M.; He, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Qian, T.; Yan, C. Covalent organic frameworks towards photocatalytic applications: Design principles, achievements, and opportunities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 475, 214882.

- Yu, A.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, M.; Xie, D.; Tang, Y. Fast rate and long life potassium-ion based dual-ion battery through 3D porous organic negative electrode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2001440.

- Yang, X.; Hu, Y.; Dunlap, N.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Su, Z.; Sharma, S.; Jin, Y.; Huang, F.; Wang, X. A truxenone-based covalent organic framework as an all-solid-state lithium-ion battery cathode with high capacity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 20385–20389.

- Haldar, S.; Rase, D.; Shekhar, P.; Jain, C.; Vinod, C.P.; Zhang, E.; Shupletsov, L.; Kaskel, S.; Vaidhyanathan, R. Incorporating Conducting Polypyrrole into a Polyimide COF for Carbon-Free Ultra-High Energy Supercapacitor. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200754.

- Shah, R.; Ali, S.; Raziq, F.; Ali, S.; Ismail, P.M.; Shah, S.; Iqbal, R.; Wu, X.; He, W.; Zu, X.; et al. Exploration of metal organic frameworks and covalent organic frameworks for energy-related applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 477, 214968.

- Ma, L.; Wang, S.; Feng, X.; Wang, B. Recent advances of covalent organic frameworks in electronic and optical applications. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 1383–1394.

- Sun, B.; Li, X.; Feng, T.; Cai, S.; Chen, T.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y. Resistive switching memory performance of two-dimensional polyimide covalent organic framework films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 51837–51845.

- Hao, Q.; Li, Z.J.; Bai, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, Y.W.; Wan, L.J.; Wang, D. A covalent organic framework film for three-state near-infrared electrochromism and a molecular logic gate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 133, 12606–12611.

- Zhou, K.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, G.; Ma, X.-Q.; Niu, W.; Han, S.-T.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y.J. Covalent Organic Frameworks for Neuromorphic Devices. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 7173–7192.

- Yu, H.; Zhou, P.K.; Chen, X. Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding Interactions Induced Enhancement in Resistive Switching Memory Performance for Covalent Organic Framework-Based Memristors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2308336.

- Ding, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, K.; Zheng, Q.; Han, S.-T.; Peng, X.; Zhou, Y. Porous crystalline materials for memories and neuromorphic computing systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 7071–7136.

- Zhou, P.K.; Yu, H.; Huang, W.; Chee, M.Y.; Wu, S.; Zeng, T.; Lim, G.J.; Xu, H.; Yu, Z.; Li, H. Photoelectric Multilevel Memory Device based on Covalent Organic Polymer Film with Keto–Enol Tautomerism for Harsh Environments Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 2306593.

- Zhou, P.K.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X. Recent advances in covalent organic polymers-based thin films as memory devices. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 1.

- Gu, Q.; Zha, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Yao, W.; Liu, J.; Kang, F.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.Y.; Lei, D. Constructing Chiral Covalent-Organic Frameworks for Circularly Polarized Light Detection. Adv. Mater. 2023, 2306414.

- Xu, F.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Wu, D.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Gu, C.; Fu, R.; Jiang, D. Radical covalent organic frameworks: A general strategy to immobilize open-accessible polyradicals for high-performance capacitive energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 127, 6918–6922.

- Xu, F.; Yang, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Wei, B.; Jiang, D. Energy-storage covalent organic frameworks: Improving performance via engineering polysulfide chains on walls. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 6001–6006.

- Wu, J.; Xu, F.; Li, S.; Ma, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Fu, R.; Wu, D. Porous polymers as multifunctional material platforms toward task-specific applications. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1802922.

- Zhuang, R.; Zhang, X.; Qu, C.; Xu, X.; Yang, J.; Ye, Q.; Liu, Z.; Kaskel, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, H. Fluorinated porous frameworks enable robust anode-less sodium metal batteries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh8060.

- Wu, T.; He, Q.; Liu, Z.; Shao, B.; Liang, Q.; Pan, Y.; Huang, J.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.J. Tube wall delamination engineering induces photogenerated carrier separation to achieve photocatalytic performance improvement of tubular g-C3N4. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127177.

- Gu, C.-C.; Xu, F.-H.; Zhu, W.-K.; Wu, R.-J.; Deng, L.; Zou, J.; Weng, B.-C.; Zhu, R.-L. Recent advances on covalent organic frameworks (COFs) as photocatalysts: Different strategies for enhancing hydrogen generation. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 7302–7320.

- Reza, M.S.; Ahmad, N.B.H.; Afroze, S.; Taweekun, J.; Sharifpur, M.; Azad, A.K. Hydrogen Production from Water Splitting through Photocatalytic Activity of Carbon-Based Materials. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2023, 46, 420–434.

- Hou, H.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X. Production of Hydrogen Peroxide by Photocatalytic Processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17356–17376.

- Di, T.; Xu, Q.; Ho, W.; Tang, H.; Xiang, Q.; Yu, J. Review on metal sulphide-based Z-scheme photocatalysts. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 1394–1411.

- Teranishi, M.; Naya, S.-I.; Tada, H. In situ liquid phase synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from molecular oxygen using gold nanoparticle-loaded titanium (IV) dioxide photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7850–7851.

- Tsukamoto, D.; Shiro, A.; Shiraishi, Y.; Sugano, Y.; Ichikawa, S.; Tanaka, S.; Hirai, T. Photocatalytic H2O2 Production from Ethanol/O2 System Using TiO2 Loaded with Au–Ag Bimetallic Alloy Nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 599–603.

More