Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jessie Wu and Version 1 by Janusz Blasiak.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is an eye disease and the most common cause of vision loss in the Western World. In its advanced stage, AMD occurs in two clinically distinguished forms, dry and wet, but only wet AMD is treatable. However, the treatment based on repeated injections with vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) antagonists may at best stop the disease progression and prevent or delay vision loss but without an improvement of visual dysfunction. Moreover, it is a serious mental and financial burden for patients and may be linked with some complications.

- age-related macular degeneration

- AMD

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGF

- anti-VEGF therapy

1. Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is an eye disease and a serious problem in aging societies [1]. Advanced AMD presents two clinically distinct forms: dry (atrophic) and wet (exudative, neovascular) [2]. Both forms may lead to legal blindness and sight loss, but currently, only wet AMD is treatable by intravitreal injections with antibodies to vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and its receptor (anti-VEGFA therapy) [3,4][3][4]. However, usually wet AMD treatment does not result in a cure for the disease, but at best stops its progression, preventing or delaying sight loss. In addition, the treatment is troublesome for patients as it includes repeated injections into one eye or both eyes and constitutes a serious financial burden for the patients. An alternative for resistance to or intolerance of anti-VEGFA treatment is photodynamic therapy, which may be applied along with the anti-VEGFA treatment [5,6][5][6].

Although anti-VEGFA treatment is a targeted therapy, it is not free from detrimental side effects that may lead to damage to the eye. Some dietary interventions may improve these effects and the efficacy of anti-VEGFA therapy, but the effects depend on many factors that may be difficult to anticipate [7]. Moreover, some patients display resistance to this kind of therapy [8].

In 2008, three independent research groups reported a successful subretinal injection of an AAV-based expression vector carrying the retinoid isomerohydrolase RPE65 (retinal pigment epithelium-specific 65 KDa protein) gene to improve vision in individuals with inherited blindness (Leber’s congenital amaurosis) [9,10,11][9][10][11]. This resulted in the first FDA-approved gene therapy product for the eye—Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl). However, possibly more important was that this initial success of gene therapy in the eye contributed to the rejuvenation of gene therapy in general after its serious setback associated with the death of a patient inspired a deeper look into the biology of virus vectors [12,13][12][13]. These experiments set the groundwork for the development of gene therapies for AMD.

Good and bad experiences of gene therapy enabled the elaboration of the strategy of safe and efficient cargo delivery by the vectors derived from adeno-associated viruses [14]. Consequently, recent studies on gene therapy in wet AMD have revolutionized the perspective of the treatment of this disease [15]. Instead of a replacement of faulty or lacking protein with its functional counterpart, new therapies direct the eye to synthesize anti-VEGF drugs. These therapies eliminate the burden of multiple intravitreal injections, offering a stable production of anti-VEGF proteins for a long time. The results obtained so far in ongoing and completed clinical trials are promising, but some aspects concerning safety and efficacy need further studies (https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Wet+Age-related+Macular+Degeneration&term=VEGF+gene+therapy&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search&type=Intr, accessed on 15 January 2024).

2. Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Pathogenesis and Therapy

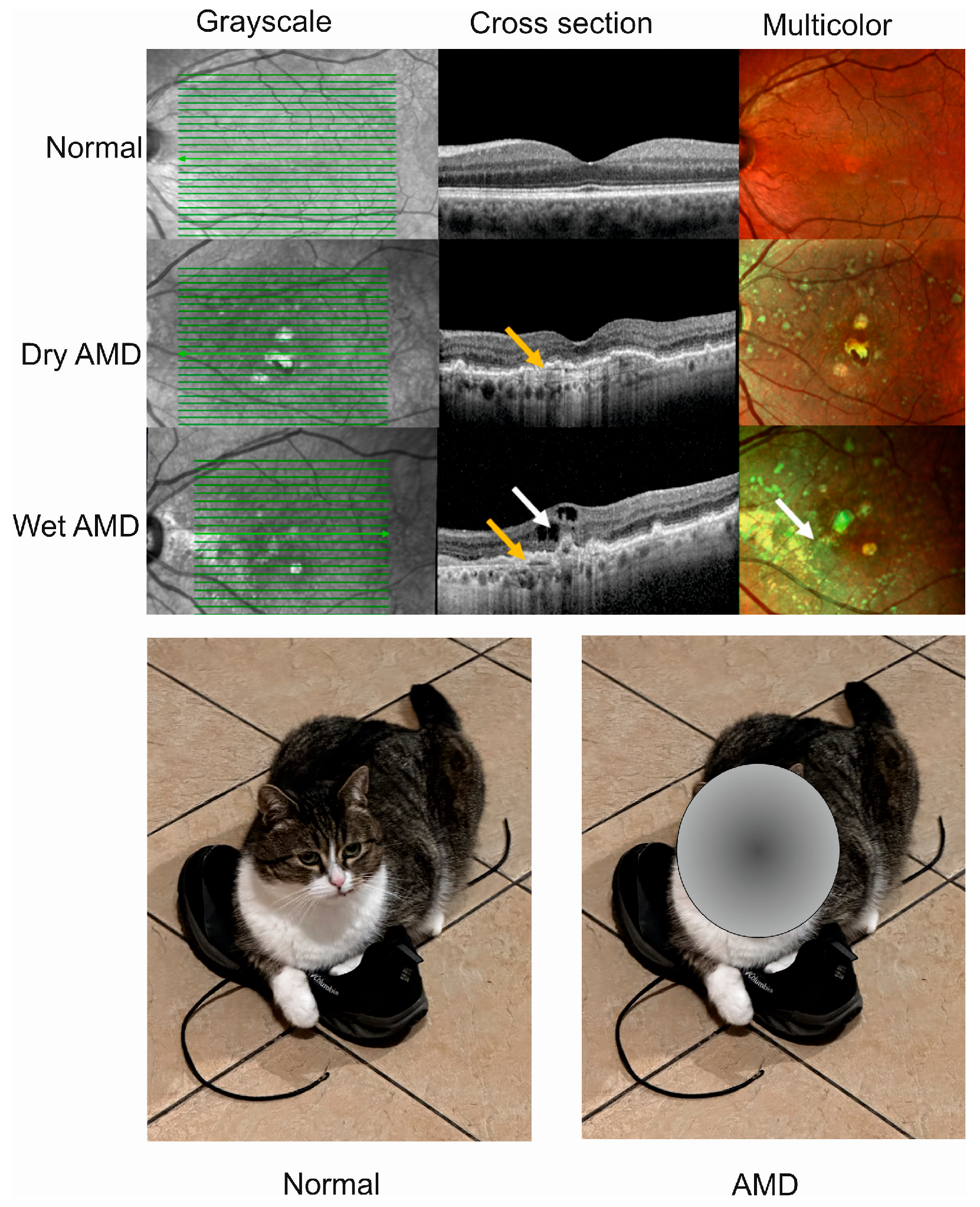

Age-related macular degeneration is a complex, multifactorial disease with aging, environmental/lifestyle, and genetic/epigenetic factors playing a role in its pathogenesis [17][16]. The complexity of this disease is also underlined in that each of these elements has several variants that may interplay both within each group of factors and with factors from a different group. For instance, AMD is not a monogenic disease, and as shown in genome-wide association studies, several genetic loci may be involved in its pathogenesis, containing genes of the following three main pathways: the complement pathway, lipid metabolism, and extracellular matrix remodeling. Variants of these genes may interact and their effect can be modulated by environmental/lifestyle AMD risk factors, including an unhealthy diet [18][17]. The most consistently reported loci that are associated with AMD are the rs1061170 (Tyr402His/p.Y402H) single nucleotide polymorphism variant in the complement factor H (CHF) and the age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2 and high-temperature requirement A serine peptidase 1 (ARMS2/HTRA1) [19,20][18][19]. Therefore, many mechanisms may be involved in AMD pathogenesis which, along with the limited possibility of studying live human eyes, results in limited treatment options for AMD. Advanced AMD happens in two clinically distinct forms, dry and wet, and individuals affected by either form may suffer from gaps or dark spots in their vision (Figure 1). Although wet AMD is responsible for a minority of all AMD cases, it accounts for about 90% of sight loss related to AMD and, somewhat paradoxically, only wet AMD is treatable [21][20]. The causal relationship, if any, between these two forms of AMD is not clear, and some studies suggest that they might be considered as two distinct diseases [22][21]. WResearchers showed that wet AMD might correlate with mortality in a 12-year prospective case–control study, but the question of whether wet AMD might be an independent risk factor for death is still open [23][22].

Figure 1. Advanced age-related macular degeneration (AMD) presents two clinically distinct forms: dry and wet. Optical coherence tomography of normal, dry AMD, and wet AMD eyes (upper panel). Yellow arrows indicate degenerated retinal pigment epithelial layers (green lines) and a white arrow shows edema and intraretinal fluid observed in cross-sectional view corresponding to increased intensity of green color in the multicolor image. Advanced AMD causes disturbances in or loss of central vision (lower panel).

3. Gene Therapy for Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration

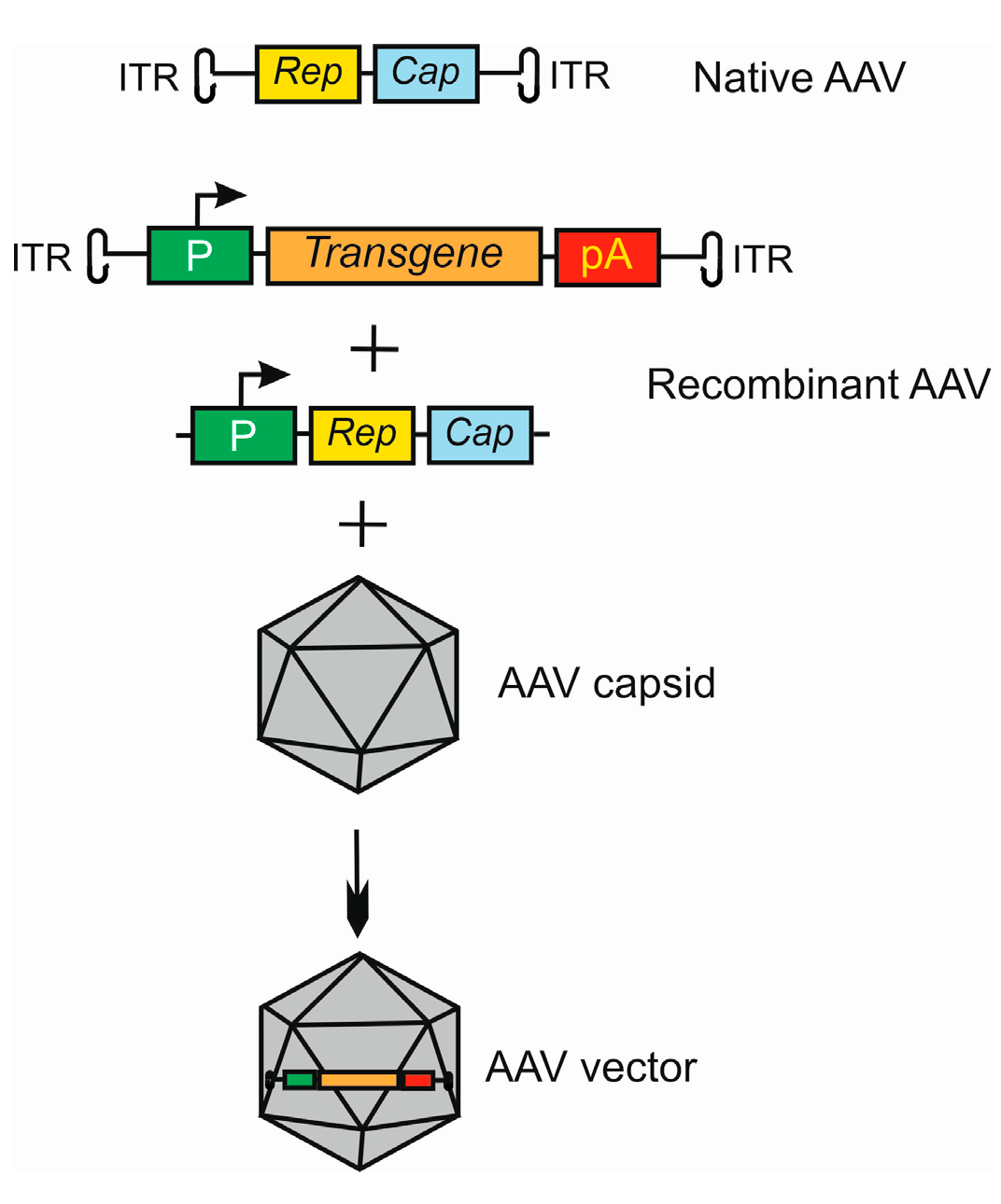

The eye seems to be predisposed as a target for gene therapy due to its relatively small size, with a compartmentalized structure and immune-privileged status [16][32]. These eye characteristics lower the risk of systemic exposure. Moreover, advanced non-invasive methods of imaging in the eye, including optical coherence tomography, fundoscopy, angiography, and two-photon microscopy, assist in the real-time monitoring of the progress of the gene therapy procedures and their safety [33]. Another advantageous feature of the eye for gene therapy is that changes in a single gene may be associated with various clinical states. For example, homozygous mutation in the “historic” RPE65 gene may result in either Leber’s congenital amaurosis 2 or rare forms of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) [34]. The development of gene therapy has brought a better understanding of the biology of viral vectors, as they are basic vectors used in eye gene therapy [35]. In general, virus vectors can be divided into integrating and non-integrating with the host genome. Due to safety concerns, non-integrating viral vectors may be the current strategies and those used in at least the near future for transgene delivery in gene therapy [36]. Among many non-integrating viral vector types, adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors have many features of key significance for eye gene therapy [37]. Adeno-associated viruses consist of two parts, an icosahedral protein capsid and a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome [38,39,40][38][39][40]. The AAV genome has 4.8 kb of ssDNA and two T-shaped inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), on either end of the genome [41] (Figure 2). The terminal repeats flank two open reading frames, Rep and Cap, that are transcribed and translated to produce the virus life cycle proteins Rep78, Rep68, Rep52, Rep40, and VP1, VP2, and VP3 capsid proteins resulting from the use of alternate promoters and alternate splicing.

Figure 2. Basic strategy of the use of adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector in gene therapy. The AVV genome contains two open reading frames (ORFs), Rep and Cap, flanked by two inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). Recombinant AAV is formed by replacing ORFs with an expressional cassette containing a promoter (P), and a transgene that may also be an RNA molecule and terminator, here a polyadenylation sequence (pA). The Rep and Cap are added in trans. This construct is packaged into the AAV capsid to form an AAV vector. Many variants of this procedure may be applied, dependent on the tropism and serotype of AAV in conjunction with target cell and tissue type.

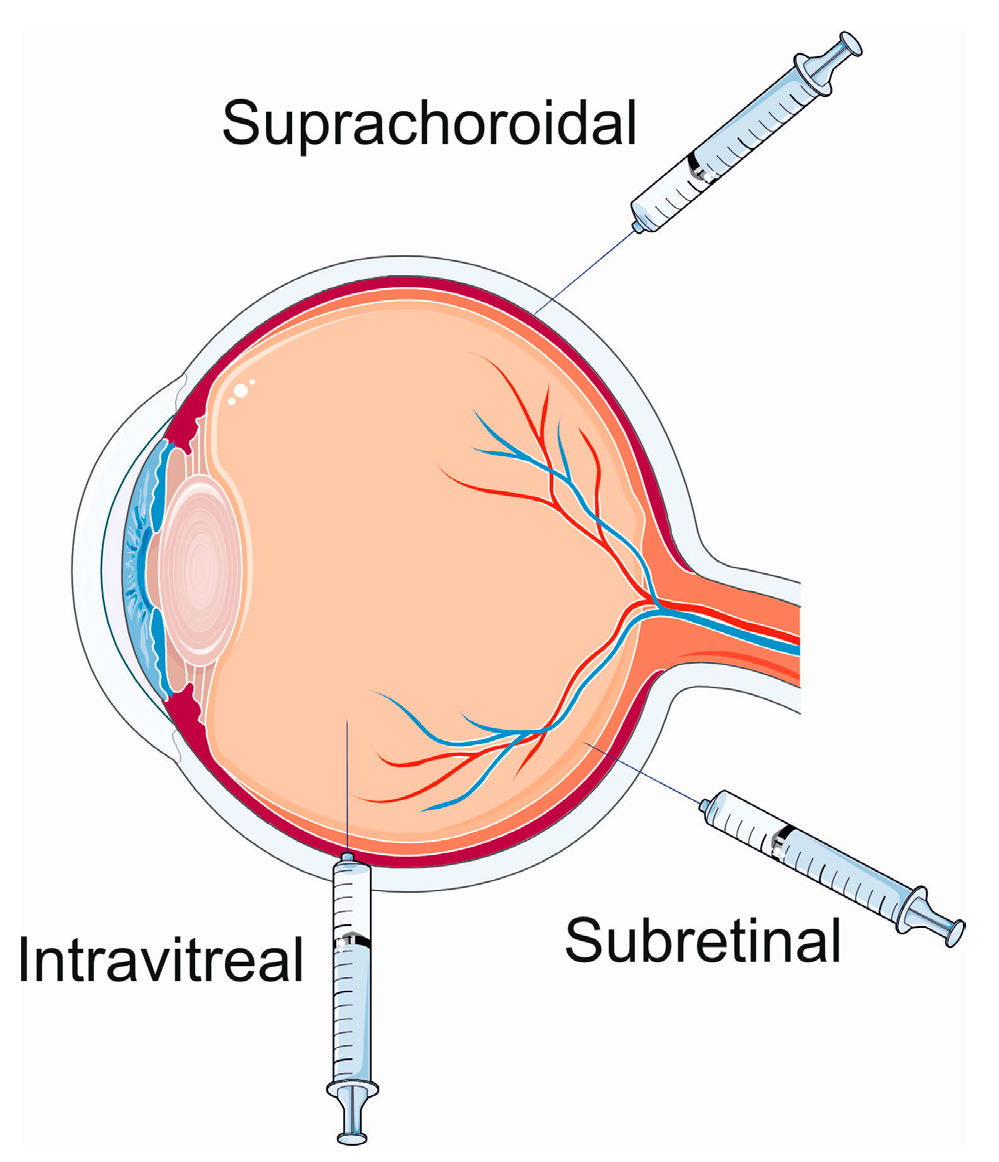

Figure 3. Ocular gene therapy delivery routes. Parts of this figure were drawn by using pictures from Servier Medical Art. Servier Medical Art by Servier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/, accessed on 15 January 2024).

References

- Flores, R.; Carneiro, Â.; Vieira, M.; Tenreiro, S.; Seabra, M.C. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Pathophysiology, Management, and Future Perspectives. Ophthalmologica 2021, 244, 495–511.

- Stahl, A. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2020, 117, 513–520.

- Granstam, E.; Aurell, S.; Sjövall, K.; Paul, A. Switching anti-VEGF agent for wet AMD: Evaluation of impact on visual acuity, treatment frequency and retinal morphology in a real-world clinical setting. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 259, 2085–2093.

- Miller, J.W. VEGF: From Discovery to Therapy: The Champalimaud Award Lecture. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2016, 5, 9.

- Oncel, D.; Oncel, D.; Mishra, K.; Oncel, M.; Arevalo, J.F. Current Management of Subretinal Hemorrhage in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmologica 2023, 246, 295–305.

- Han, X.; Chen, Y.; Gordon, I.; Safi, S.; Lingham, G.; Evans, J.; Keel, S.; He, M. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Age-related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2023, 30, 213–220.

- Blasiak, J.; Chojnacki, J.; Szczepanska, J.; Fila, M.; Chojnacki, C.; Kaarniranta, K.; Pawlowska, E. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate, an Active Green Tea Component to Support Anti-VEGFA Therapy in Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3358.

- Yang, S.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X. Resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A comprehensive review. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 1857–1867.

- Bainbridge, J.W.; Smith, A.J.; Barker, S.S.; Robbie, S.; Henderson, R.; Balaggan, K.; Viswanathan, A.; Holder, G.E.; Stockman, A.; Tyler, N.; et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2231–2239.

- Hauswirth, W.W.; Aleman, T.S.; Kaushal, S.; Cideciyan, A.V.; Schwartz, S.B.; Wang, L.; Conlon, T.J.; Boye, S.L.; Flotte, T.R.; Byrne, B.J.; et al. Treatment of leber congenital amaurosis due to RPE65 mutations by ocular subretinal injection of adeno-associated virus gene vector: Short-term results of a phase I trial. Hum. Gene Ther. 2008, 19, 979–990.

- Maguire, A.M.; Simonelli, F.; Pierce, E.A.; Pugh, E.N., Jr.; Mingozzi, F.; Bennicelli, J.; Banfi, S.; Marshall, K.A.; Testa, F.; Surace, E.M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2240–2248.

- Dunbar, C.E.; High, K.A.; Joung, J.K.; Kohn, D.B.; Ozawa, K.; Sadelain, M. Gene therapy comes of age. Science 2018, 359, eaan4672.

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; von Kalle, C.; Schmidt, M.; Le Deist, F.; Wulffraat, N.; McIntyre, E.; Radford, I.; Villeval, J.L.; Fraser, C.C.; Cavazzana-Calvo, M.; et al. A serious adverse event after successful gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 255–256.

- Wang, D.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 358–378.

- Khanani, A.M.; Thomas, M.J.; Aziz, A.A.; Weng, C.Y.; Danzig, C.J.; Yiu, G.; Kiss, S.; Waheed, N.K.; Kaiser, P.K. Review of gene therapies for age-related macular degeneration. Eye 2022, 36, 303–311.

- Fleckenstein, M.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Guymer, R.H.; Chakravarthy, U.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 31.

- Acar, I.E.; Galesloot, T.E.; Luhmann, U.F.O.; Fauser, S.; Gayán, J.; den Hollander, A.I.; Nogoceke, E. Whole Genome Sequencing Identifies Novel Common and Low-Frequency Variants Associated With Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 24.

- Grassmann, F.; Heid, I.M.; Weber, B.H. Recombinant Haplotypes Narrow the ARMS2/HTRA1 Association Signal for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Genetics 2017, 205, 919–924.

- Park, D.H.; Connor, K.M.; Lambris, J.D. The Challenges and Promise of Complement Therapeutics for Ocular Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1007.

- Gabrielle, P.H.; Maitrias, S.; Nguyen, V.; Arnold, J.J.; Squirrell, D.; Arnould, L.; Sanchez-Monroy, J.; Viola, F.; O’Toole, L.; Barthelmes, D.; et al. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of submacular haemorrhage with loss of vision in neovascular age-related macular degeneration in daily clinical practice: Data from the FRB! registry. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, e1569–e1578.

- Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Wilkinson, C.P.; Bird, A.; Chakravarthy, U.; Chew, E.; Csaky, K.; Sadda, S.R. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 844–851.

- Blasiak, J.; Watala, C.; Tuuminen, R.; Kivinen, N.; Koskela, A.; Uusitalo-Järvinen, H.; Tuulonen, A.; Winiarczyk, M.; Mackiewicz, J.; Zmorzyński, S.; et al. Expression of VEGFA-regulating miRNAs and mortality in wet AMD. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 8464–8471.

- Curcio, C.A. Soft Drusen in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Biology and Targeting Via the Oil Spill Strategies. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, Amd160–Amd181.

- Park, S.W.; Im, S.; Jun, H.O.; Lee, K.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, W.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, J.H. Dry age-related macular degeneration like pathology in aged 5XFAD mice: Ultrastructure and microarray analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 40006–40018.

- Hobbs, S.D.; Pierce, K. Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration (Wet AMD). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023.

- Karampelas, M.; Malamos, P.; Petrou, P.; Georgalas, I.; Papaconstantinou, D.; Brouzas, D. Retinal Pigment Epithelial Detachment in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2020, 9, 739–756.

- Chaikitmongkol, V.; Bressler, S.B.; Bressler, N.M. Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): Non-neovascular and Neovascular AMD. In Albert and Jakobiec’s Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology; Albert, D.M., Miller, J.W., Azar, D.T., Young, L.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3565–3617.

- Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Hartnett, M.E. VEGFA activates erythropoietin receptor and enhances VEGFR2-mediated pathological angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 1230–1239.

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Chong, V.; Loewenstein, A.; Larsen, M.; Souied, E.; Schlingemann, R.; Eldem, B.; Monés, J.; Richard, G.; Bandello, F. Guidelines for the management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 98, 1144–1167.

- Lu, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, H.; Ren, G.; Shi, F.; Kuang, L.; Yan, S.; et al. Factors for Visual Acuity Improvement after Anti-VEGF Treatment of Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration in China: 12 Months Follow up. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 735318.

- Schauwvlieghe, A.M.; Dijkman, G.; Hooymans, J.M.; Verbraak, F.D.; Hoyng, C.B.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; Peto, T.; Vingerling, J.R.; Schlingemann, R.O. Comparing the Effectiveness of Bevacizumab to Ranibizumab in Patients with Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration. The BRAMD Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153052.

- Choi, E.H.; Suh, S.; Sears, A.E.; Hołubowicz, R.; Kedhar, S.R.; Browne, A.W.; Palczewski, K. Genome editing in the treatment of ocular diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1678–1690.

- Ringel, M.J.; Tang, E.M.; Tao, Y.K. Advances in multimodal imaging in ophthalmology. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2021, 13, 25158414211002400.

- Talib, M.; van Schooneveld, M.J.; van Duuren, R.J.G.; Van Cauwenbergh, C.; Ten Brink, J.B.; De Baere, E.; Florijn, R.J.; Schalij-Delfos, N.E.; Leroy, B.P.; Bergen, A.A.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Retinal Degenerations Associated with LRAT Mutations and Their Comparability to Phenotypes Associated with RPE65 Mutations. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 24.

- Bulcha, J.T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 53.

- Ghosh, S.; Brown, A.M.; Jenkins, C.; Campbell, K. Viral Vector Systems for Gene Therapy: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Progress and Biosafety Challenges. Appl. Biosaf. 2020, 25, 7–18.

- Kessler, P.D.; Podsakoff, G.M.; Chen, X.; McQuiston, S.A.; Colosi, P.C.; Matelis, L.A.; Kurtzman, G.J.; Byrne, B.J. Gene delivery to skeletal muscle results in sustained expression and systemic delivery of a therapeutic protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14082–14087.

- Drouin, L.M.; Agbandje-McKenna, M. Adeno-associated virus structural biology as a tool in vector development. Future Virol. 2013, 8, 1183–1199.

- Xie, Q.; Bu, W.; Bhatia, S.; Hare, J.; Somasundaram, T.; Azzi, A.; Chapman, M.S. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10405–10410.

- Zengel, J.; Carette, J.E. Structural and cellular biology of adeno-associated virus attachment and entry. Adv. Virus Res. 2020, 106, 39–84.

- Bennett, A.; Mietzsch, M.; Agbandje-McKenna, M. Understanding capsid assembly and genome packaging for adeno-associated viruses. Future Virol. 2017, 12, 283–297.

- Pillay, S.; Zou, W.; Cheng, F.; Puschnik, A.S.; Meyer, N.L.; Ganaie, S.S.; Deng, X.; Wosen, J.E.; Davulcu, O.; Yan, Z.; et al. Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) Serotypes Have Distinctive Interactions with Domains of the Cellular AAV Receptor. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128.

- Maurer, A.C.; Weitzman, M.D. Adeno-Associated Virus Genome Interactions Important for Vector Production and Transduction. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 499–511.

- Bessis, N.; GarciaCozar, F.J.; Boissier, M.C. Immune responses to gene therapy vectors: Influence on vector function and effector mechanisms. Gene Ther. 2004, 11 (Suppl. 1), S10–S17.

- Kotin, R.M.; Siniscalco, M.; Samulski, R.J.; Zhu, X.D.; Hunter, L.; Laughlin, C.A.; McLaughlin, S.; Muzyczka, N.; Rocchi, M.; Berns, K.I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 2211–2215.

- Au, H.K.E.; Isalan, M.; Mielcarek, M. Gene Therapy Advances: A Meta-Analysis of AAV Usage in Clinical Settings. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 809118.

- Rodrigues, G.A.; Shalaev, E.; Karami, T.K.; Cunningham, J.; Slater, N.K.H.; Rivers, H.M. Pharmaceutical Development of AAV-Based Gene Therapy Products for the Eye. Pharm. Res. 2018, 36, 29.

- de Smet, M.D.; Lynch, J.L.; Dejneka, N.S.; Keane, M.; Khan, I.J. A Subretinal Cell Delivery Method via Suprachoroidal Access in Minipigs: Safety and Surgical Outcomes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 311–320.

- Naftali Ben Haim, L.; Moisseiev, E. Drug Delivery via the Suprachoroidal Space for the Treatment of Retinal Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 967.

- Wu, K.Y.; Fujioka, J.K.; Gholamian, T.; Zaharia, M.; Tran, S.D. Suprachoroidal Injection: A Novel Approach for Targeted Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1241.

- Ladha, R.; Caspers, L.E.; Willermain, F.; de Smet, M.D. Subretinal Therapy: Technological Solutions to Surgical and Immunological Challenges. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 846782.

- Anderson, W.J.; da Cruz, N.F.S.; Lima, L.H.; Emerson, G.G.; Rodrigues, E.B.; Melo, G.B. Mechanisms of sterile inflammation after intravitreal injection of antiangiogenic drugs: A narrative review. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2021, 7, 37.

- Hartman, R.R.; Kompella, U.B. Intravitreal, Subretinal, and Suprachoroidal Injections: Evolution of Microneedles for Drug Delivery. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 34, 141–153.

- Kiser, P.D. Retinal pigment epithelium 65 kDa protein (RPE65): An update. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 88, 101013.

More