Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Marek Zieliński.

Organic farms should, by definition, place particular emphasis on the protection of agricultural soils, landscape care and activities aimed at producing high-quality agricultural products. In Poland, its development strength largely depends on the presence of areas facing natural or other specific constraints (ANCs). Nearly ¾ of organic utilized agriculture area (UAA) is located in communes with a large share of them. Organic farms achieve lower production effects in comparison to conventional farms, and their disproportions also depend on the quality of natural farming conditions. In Poland, the personal competences of farmers are also an important determinant in joining organic farming.

- areas facing natural or other specific constraints (ANCs)

- EU CAP

- Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN)

- organic farms

1. Introduction

Globally, negative changes in the natural environment are currently intensifying, often caused by agriculture [1,2][1][2]. The process results not only from the intensification of production in areas with favorable natural conditions for production, but also from the simultaneous abandonment of land that is particularly difficult to cultivate [3,4,5,6,7][3][4][5][6][7]. Thus, agriculture largely contributes to increased degradation of the natural environment [8,9][8][9]. This state of affairs results in the opinion that in order for agriculture to have a positive impact on its condition, it requires the presence of permanent and stable institutional rules of conduct consistent with social interest.

In the European Union (EU), in supporting agriculture in its efforts to protect the natural environment, an important role is played by the set of standards, regulations and incentives included in the European Green Deal (EGD) strategy of 2019, in its thematic strategies for 2020–2022, and also in the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), revised every few years, which increasingly emphasizes the role of institutional activities aimed at meeting society’s needs in terms of the consumption of high-quality agricultural goods and the stable and sustainable acquisition of a wide range of environmental goods [10,11,12][10][11][12]. One of the most important of them is the organic farming measure [13]. This measure has been a permanent part of European agricultural policy for many years, serving to promote in agriculture the agricultural production system that is most consistent with the social interest in order to effectively overcome the progressive degradation of the natural environment [14]. Financial support is provided to farmers who voluntarily decide to stop using conventional practices in agricultural production, including the use of chemical plant protection products and artificial fertilizers. As a result, this situation improves the quality of food offered by organic farms, ensures public health and brings a number of non-market benefits to the natural environment [15]. Moreover, participation of farms in this measure is often a real chance to improve their economic situation, due to the possibility of obtaining additional payments, selling certified organic products and developing agritourism. However, farms joining the organic farming system face many challenges. First of all, they must cope with a lower supply of nutrients in the soil and a limited ability to effectively combat weeds, pests and diseases, which, as a result, are often associated with lower yields of crops, as compared to conventional agriculture [16,17,18][16][17][18]. Despite these weaknesses, the organic farming system is able to meet one of the basic objectives of the EU CAP, which concerns the need to achieve a balance in agriculture between ensuring satisfactory agricultural income and providing environmental goods to society [19,20][19][20]. However, in agriculture, an acceptable level of income is usually an important condition for effective protection of the natural environment [21,22][21][22]. This situation is particularly important in areas facing natural or other specific constraints (ANCs), where farms have limited opportunities to obtain satisfactory economic effects from conventional production. The implementation of institutional environmental measures in these areas, including organic farming under the EU CAP, is one of the important opportunities. This circumstance occurs in agriculture in Poland, where the presence of ANCs is an important determinant of greater participation in this measure. These areas play an important role in Poland [23]. Their current share in the total area of utilized agricultural area is 58.7% [24].

2. Yields Gaps between Organic and Conventional Farming

The organic farming system is a comprehensive agricultural system that uses a number of processes to ensure sustainable functioning of ecosystems, food safety, animal welfare and social justice [29][25]. Organic farming, therefore, has a positive impact on protecting the natural environment, preserving biodiversity and offering high-quality food [30][26]. However, one of the basic weaknesses of this production system, as compared to conventional agriculture, is about the often lower production effects, which is related to the production only using natural means of production, which limits the possibilities of increasing productivity [31,32][27][28]. It is also the main criticism, because in common opinion, global food production should constantly increase to feed the constantly growing population of people who, at the same time, report an increasing demand for a high-calorie diet [33,34][29][30]. On the other hand, the fact is that in reality, global food production still keeps pace with the growing demand of the world’s population, but equitable access to it remains the problem; for many people, it is limited or impossible as a result of prevailing local social, political or economic factors [35][31]. Feledyn-Szewczyk et al. [36][32] indicated that the yields of cereal crops in organic farming, as compared to conventional agriculture are, on average, 25 to 50% lower. However, Alvarez [37][33] obtained research results indicating an average difference in crop yields of 25% to the detriment of organic farming, with a larger difference in the case of cereals (30%), and a much smaller difference in the case of legumes (10%). Ponti et al. [38][34] obtained a similar strength of differences between cereals and legumes in the compared agricultural production systems. Boschiero et al. [13] received an average 22% decrease in crop yields in the organic system, as compared to the conventional one. In turn, Seufert et al. [39][35] and Seufert and Ramankutty [40][36] presented results according to which average yields of crops in this production system turned out to be lower by between 5 and 34%. A different range of disproportions in crop yields to the detriment of organic farming was the result of research by Kirchmann and Ryan [41][37], which ranged from 20% to 45%. An even greater range in the difference occurred in the analyses of Ziętara and Mirkowska [42][38] and Hagner et al. [43][39], where it ranged from 28 to 60% and 12 to 45%, respectively. In turn, a much smaller difference occurred in the study by Sacco et al. [44][40], who obtained yields of organic plants that were 12 to 29% lower than those of analogous plants grown in a conventional system. All the mentioned research results have in common the belief of their authors that in economic reality, the scale of disproportions in crop yields in the organic and conventional systems depends to a large extent on the knowledge, skills and commitment of farmers in the proper selection of agricultural practices. For the success of crops in organic farming, it is, first of all, desirable to use long crop rotation cycles; they are the basic method of stabilizing yields in the production system, including through limiting the occurrence of weeds and outbreaks of diseases and pests, large-scale cultivation of intercrops, appropriate amounts and quality of natural fertilizers, varietal progress and proper selection of crop plants, which allows better use of the natural potential of a given habitat and effectively counteracts increasing occurrence of pests, as well as plant protection using biological agents [45,46,47,48][41][42][43][44]. When these practices are used in organic farming, the documented scale of disproportions in crop yields is often much smaller. This is confirmed by the results of research by Ponisio et al. [49][45], who, using correct agrotechnics, achieved differences in yields ranging on average from 3 to 13%, to the detriment of organic farming. The existence and strength of differences in crop yields in the organic and conventional systems may also depend on natural farming conditions. The issue becomes particularly important for agriculture in Poland, which is characterized by a large share of areas with difficult or particularly difficult conditions for farming within the ANCs’ delimitation. In Poland, organic farming is very important in these areas. Therefore, the question arises about potential differences in production effects in organic and conventional farming in communes with a large share of ANCs, as compared to other communes. An attempt was made to answer this question in the final section of this study.3. The Direction of Organic Farming Development in the EU, including Poland

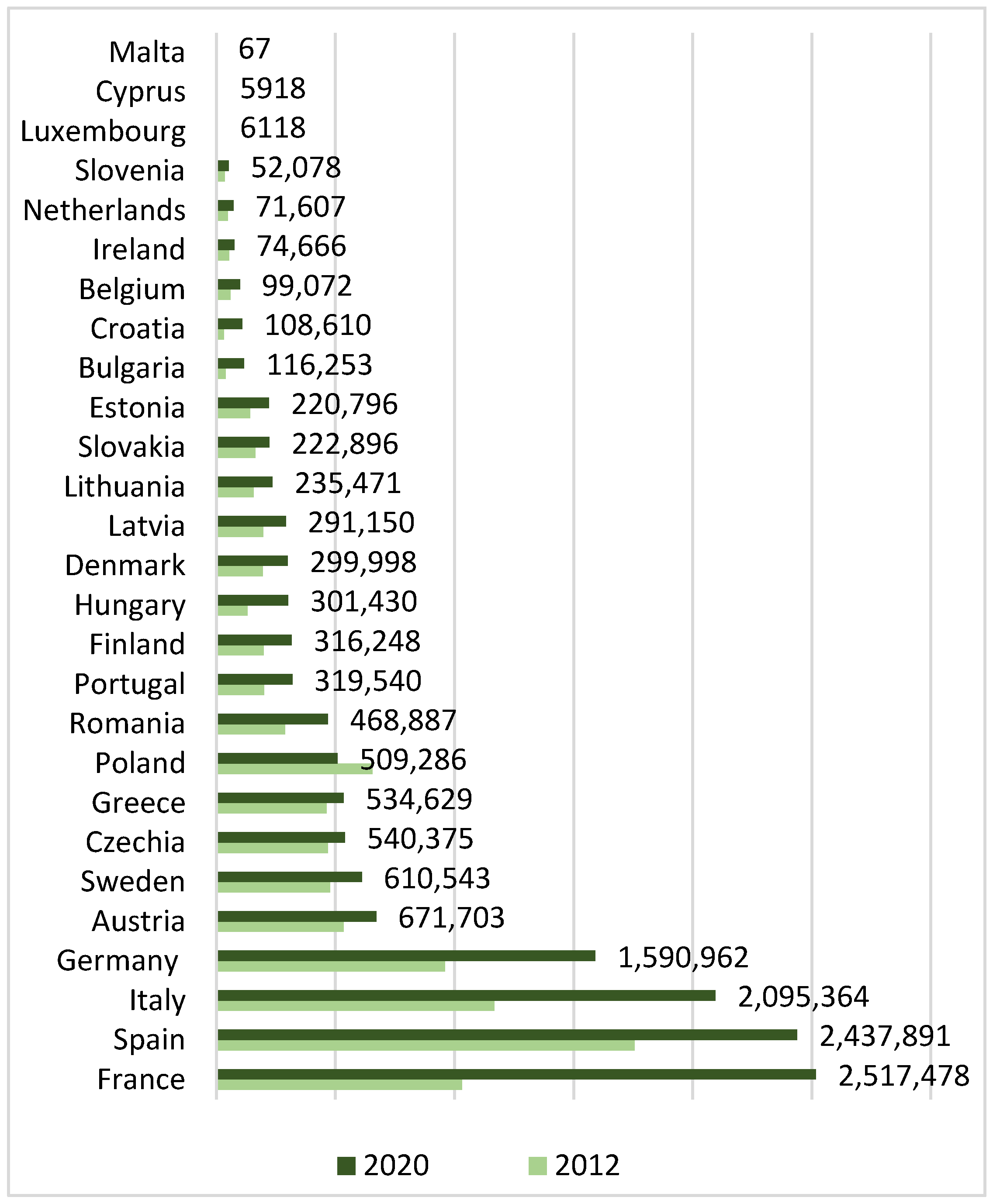

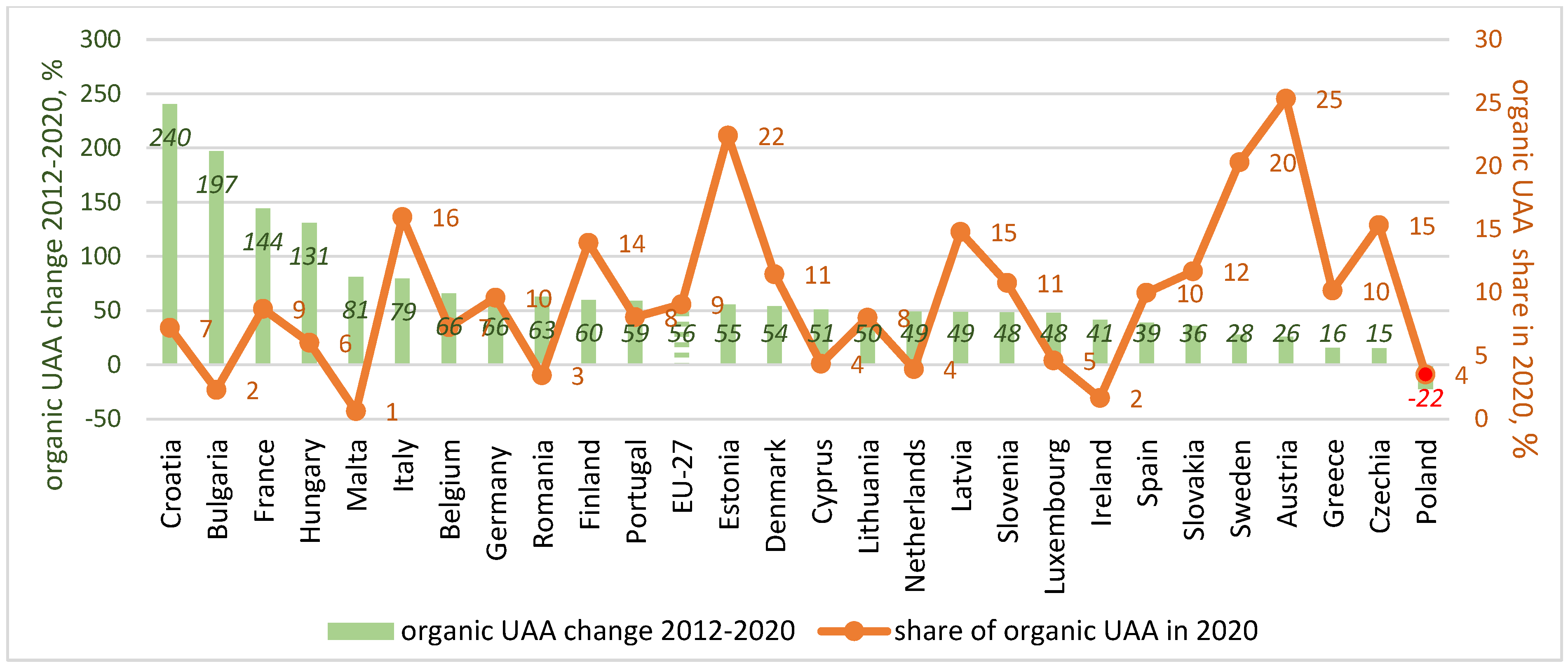

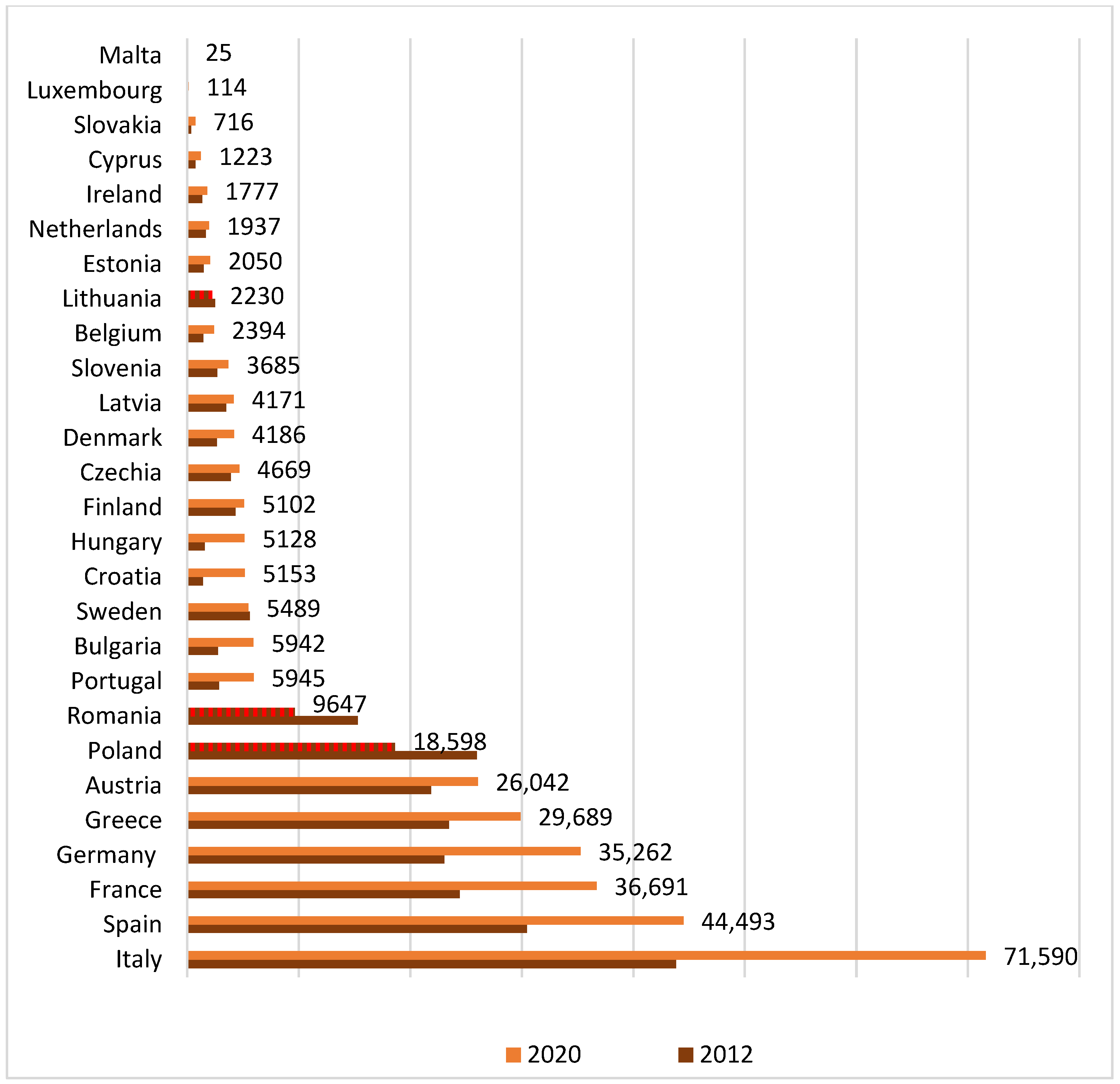

The EGD highlighted the importance of organic farming in achieving the EU environmental goals. According to the introduced European strategies, in 2030, the share of agricultural area covered by organic farming should reach 25% [50,51][46][47]. Such an ambitious goal of increasing the area of agricultural land in the organic system results from the role of those farms in shaping the natural environment, climate and society [52][48]. Based on Eurostat data, mainly for 2012 and 2020, the basic determinants of the development of organic farming in the EU (EU-27) are presented. One of the most important is the area of organic UAA, which increased by more than half in the adopted analysis period, from 9.5 million ha to 14.7 million ha. The area includes the area that was converted and which is in the process of being converted to organic farming. Currently, the area constitutes 9% of UAA intended for agricultural purposes in the EU and, when compared to the adopted strategic goal of 25%, it highlights the distance that European agriculture has to overcome in the coming years. From the perspective of the current development experience of European agriculture, the strategic goal regarding the development of organic farming is appropriate, and the direction of changes is consistent with the expected [53][49]. EU agriculture is diverse, also in the field of organic farming [52,54,55][48][50][51]. The differentiation is evidenced by both the absolute and relative difference in the area of organic UAA, as well as the pace of change in this respect in individual EU Member States (Figure 21 and Figure 32).

Figure 21.

Utilized agricultural organic farming area in EU-27 (in ha).

Figure 32. The change in organic utilized agricultural area in EU between 2012 and 2020 (%) and percentage of organic UAA in 2020 (%). UAA—utilized agricultural area.

Figure 43.

Number of agricultural organic producers in 2012 and 2020.

4. Natural Farming Conditions in Poland and the Development of Organic Farming Supported by the EU CAP

In the EU, including Poland, an important factor differentiating the possibility, direction and scale of agricultural production is the natural management conditions, which are characterized by spatial variability and a large share of ANCs (Figure 54). In the EU, the area of ANCs currently accounts for 57.9% of the total area of UAA. In Poland, the share of ANCs is close to the EU average, 58.7% [56][52]. From the point of view of the predisposition to provide society with high-quality agricultural products and a wide range of environmental goods, in Poland, the significantly greater presence of High Nature Value farmlands (HNVfs) in the total area of UAA is the advantage of communes with a high share of ANCs, as compared to communes that are the reference point [57,58][53][54].

Figure 54.

Distribution of ANCs by communes in Poland.

Table 1.

Organizational features of agriculture in communes with different saturation of ANCs in 2022 in Poland.

| Variable | Communes | |

|---|---|---|

| With a High Share of ANCs | Remaining | |

| Number of farms (thousands) | 620.6 | 631.4 |

| UAA (thousand ha), including: | 6705.4 | 7459.0 |

| arable lands (thousand ha) | 4807.8 | 6440.2 |

| permanent grasslands (thousand ha) | 1790.3 | 737.6 |

Source: own study on the basis of ARMA for 2022.

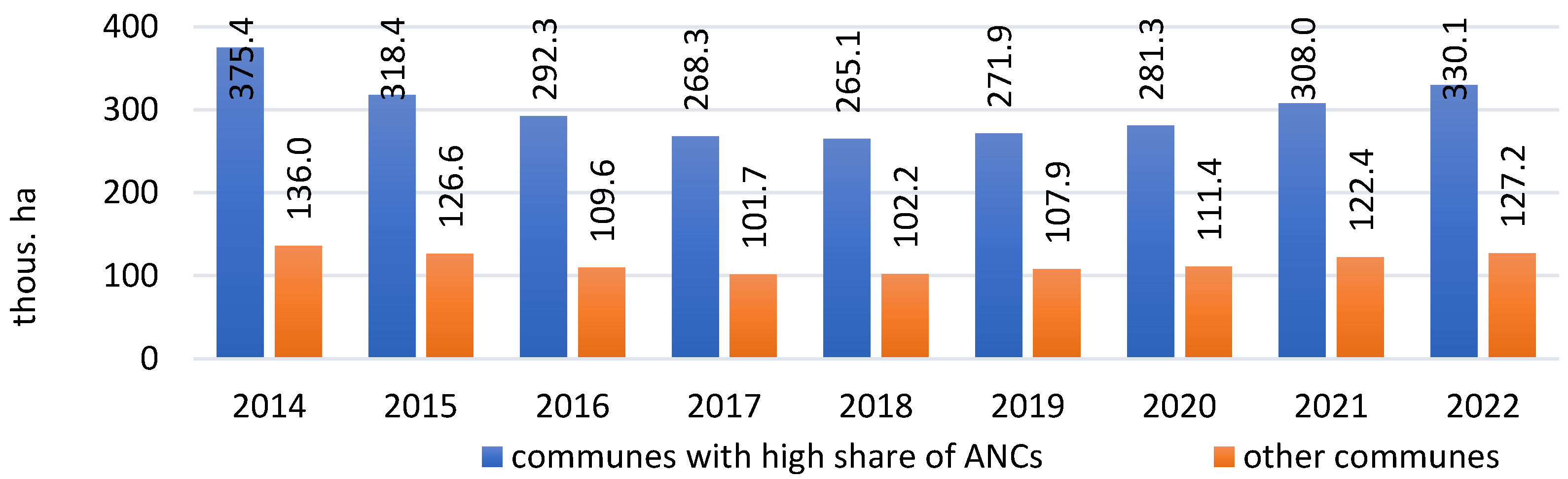

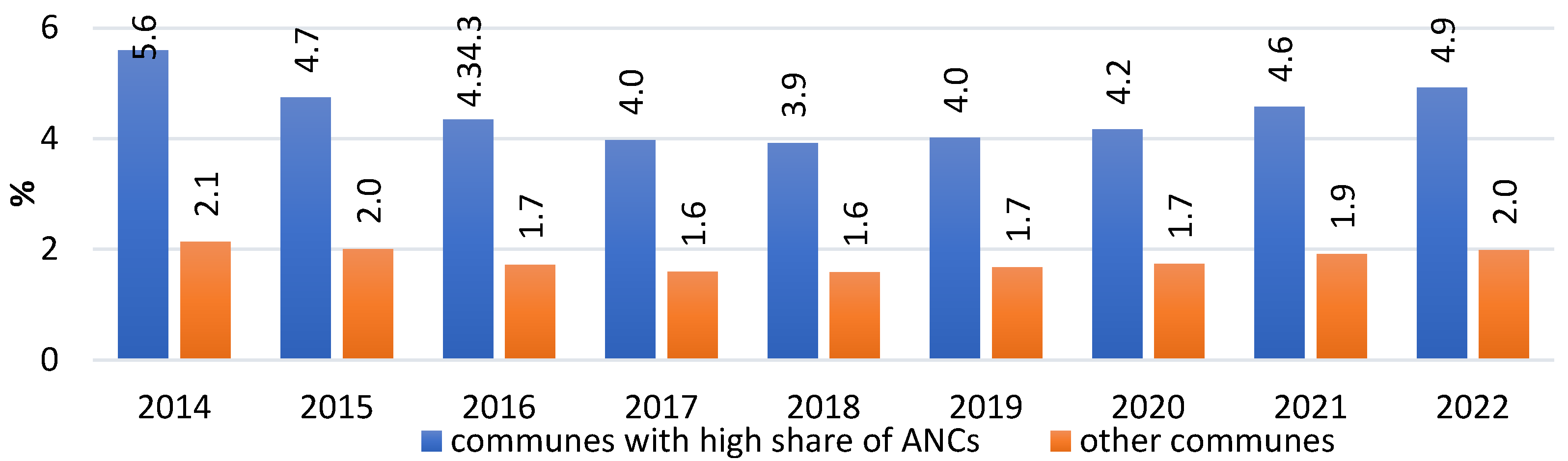

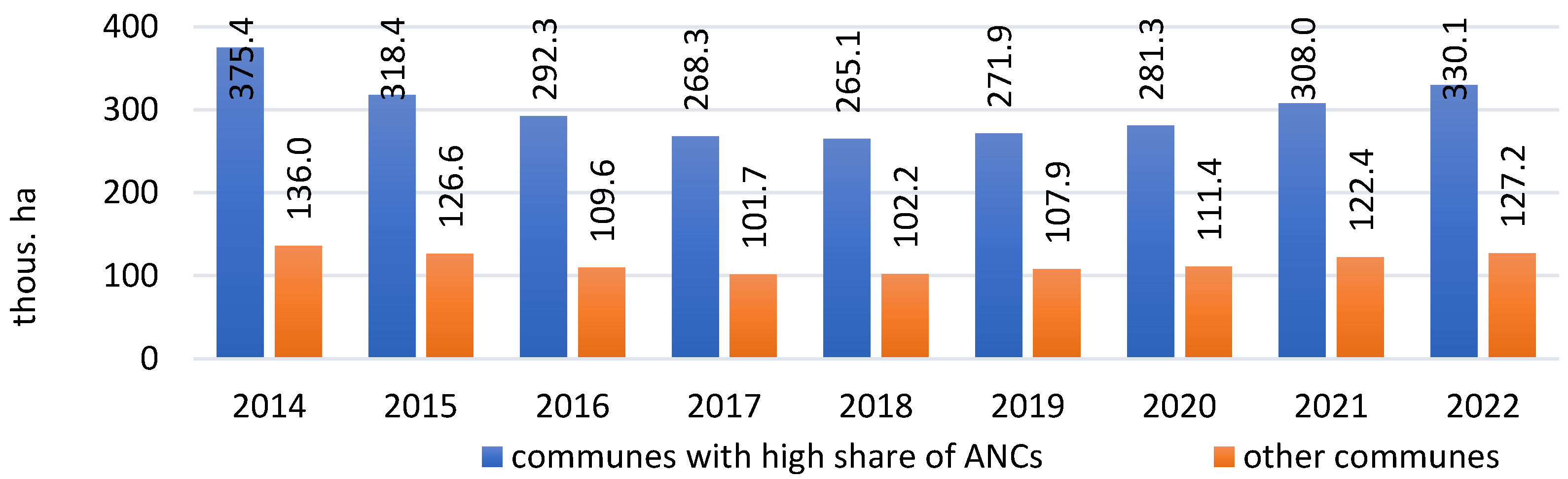

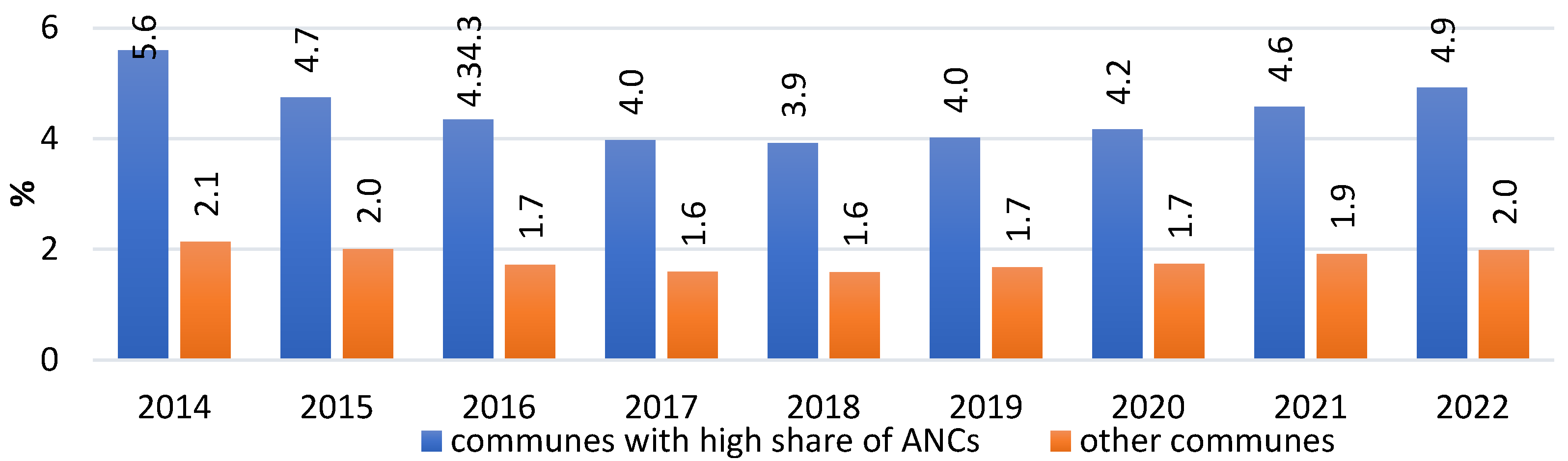

In areas with a high share of ANCs, the coexistence of diversified plant production with structural plants on arable land and animal production on permanent grasslands is one of the basic conditions for conducting profitable agricultural production. It then ensures optimal soil protection by maintaining and increasing their fertility, including through the use of natural fertilizers, as well as ensuring the good condition of the landscape, including by grazing animals. In this context, organic farming under the EU CAP has a lot to offer. This opinion is confirmed by the fact that in 2014–2022, 71.6% to 74.8% of the total area of UAA with organic farming supported under the CAP 2014–2020 was located in communes with a high share of ANCs. In addition, its share in the total area of UAA ranged from 3.9 to 5.6%, while in the remaining communes, it ranged from 1.6 to 2.1% (Figure 65, Figure 76 and Figure 87).

Figure 65.

Distribution of area supported under the organic farming measure under the EU CAP by communes in Poland in 2022.

Figure 76. UAA supported under the organic farming measure in the CAP 2014–2020 by communes with different ANCs saturation in Poland in 2014–2022 (thousand ha).

Figure 87. Share of UAA supported under the organic farming measure in the CAP 2014–2020 in total UAA by communes with different ANCs saturation in Poland in 2014–2022 (%).

References

- FAO. Emissions Due to Agriculture. Global, Regional and Country Trends 2000–2018. FAOSTAT Analytical Brief 18; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020.

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Gamage, J.; Jayasinghe, N.; Kodikara, N.; Suraweera, P.; Merah, O. Role of organic farming for achieving sustainability in agriculture. Farming Syst. 2023, 1, 100005.

- Czyżewski, A.; Stępień, S.; Nowe Uwarunkowania Ekonomiczne Wspólnej Polityki Rolnej (WPR) Unii Europejskiej. Ekonomista, nr. 6. 2017. Available online: https://ekonomista.pte.pl/pdf-155585-82414?filename=Nowe%20uwarunkowania.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Van der Zanden, E.; Verburg, P.H.; Schulp, C.J.E.; Verkerk, P.J. Trade-offs of European agricultural abandonment. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 290–301.

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019.

- CBD. Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. Montreal. 2019. Available online: http://41.89.141.8/kmfri/handle/123456789/1609 (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Zgłobicki, W.; Karczmarczuk, K.; Baran-Zgłobicka, B. Intensity and Driving Forces of Land Abandonment in Eastern Poland. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3500.

- Pe’er, G.; Bonn, A.; Bruelheide, H.; Dieker, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Feindt, P.; Hagedorn, G.; Hansurgens, B.; Herzon, I.; Lomba, A.; et al. Action needed for the EU Common Agricultural Policy to address sustainability challenges. People Nat. 2020, 2, 305–316.

- Koninger, J.; Panagos, P.; Jones, A.; Briones, M.J.I.; Orgiazzi, A. In deference of soil biodiversity: Towards an inclusive protection in the European Union. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 268, 109475.

- Lefebvre, M.; Espinosa, M.; Paloma Gomez, S.; Paracchini, M.L.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I. Agricultural landscapes as multi-scale public good and the role of the Common Agricultural Policy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 58, 2088–2112.

- Jespersen, L.M.; Baggesen, D.L.; Fog, E.; Halsnæs, K.; Hermansen, J.E.; Andreasen, L.; Strandberg, B.; Sørensen, J.T.; Halberg, N. Contribution of organic farming to public goods in Denmark. Org. Agric. 2017, 7, 243–266.

- McGurk, E.; Hynes, S.; Thorne, F. Participation in agri-environmental schemes: A contingent valuation study of farmers in Ireland. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 262, 110243.

- Boschiero, M.; De Laurentiis, V.; Caldeira, C.; Sala, S. Comparison of organic and conventional cropping systems: Asystematic review of life cicle assessment studies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 102, 107187.

- Lee, S.K.; Choe, C.Y.; Park, H.S. Measuring the environmental effects of organic farming. A meta-analysis of structural variables in empirical research. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 162, 263–274.

- Jahantab, M.; Abbasi, B.; Bodic, L.P. Farmland allocation in the conversion from conventional to organic farming. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 311, 1103–1119.

- Jarosch, K.; Oberson, A.; Frossard, E.; Lucie, G.; Dubois, D.; Mader, P.; Jochen, M. Phosphorus (P) balances and P availability in a field trial comparing organic and conventional farming systems since 35 years. In Proceedings of the 19th EGU General Assembly, EGU2017, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 April 2017.

- Schrama, M.; de Haan, J.J.; Kroonen, M.; Verstegen, H.; Van der Putten, W.H. Crop yield gap and stability in organic and conventional farming systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 123–130.

- Stubenrauch, J.; Ekardt, F.; Heyl, K.; Garske, B.; Schrott, L.V.; Ober, S. How to legally overcome the distinction between organic and conventional farming-Governance approaches for sustainable farming on 100% of the land. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 716–725.

- M’barek, R.; Barreiro_Hurle, J.; Boulanger, P.; Caivano, A.; Ciaian, P.; Dudu, H.; Espinosa, M.; Fellmann, T.; Ferrari, E.; Gomez y Paloma, S.; et al. Scenar 2030. Pathways for the European Union and Food Sector beyond 2020. Summary Report; European Comission: Luxembourg, 2017.

- Uthes, S.; Kelly, E.; Konig, H.J. Farm-level indicators for crop and landscape diversity derived from agricultural beneficiaries data. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105725.

- Finger, F.; El Benni, N. Farm income in European agriculture: New perspectives on measurement and implications for policy evaluation. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2021, 48, 253–265.

- Sidhoum, A.A.; Mennig, P.; Sauer, J. Do agri-environment measures help improve environmental and economic efficiency? Evidence from Bavarian dairy farmers. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2023, 50, 918–953.

- Krasowicz, S. Regional aspects in the work of the Institute of Soil science and plant cultivation-State Research Institute in Pulawy. Econ. Reg. Stud. 2017, 10, 110–119.

- Zieliński, M.; Józwiak, W.; Ziętara, W.; Wrzaszcz, W.; Mirkowska, Z.; Sobierajewska, J.; Adamski, M. Kierunki i Możliwości Rozwoju Rolnictwa Ekologicznego w Polsce w Ramach Europejskiego Zielonego Ładu; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- Łuczka, W.; Kalinowski, S.; Shmygol, N. Organic farming Support Policy in a Sustainable Development Context: A Polish Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 4208.

- Drygas, M.; Nurzyńska, I.; Bańkowska, K. Charakterystyka i Uwarunkowania Rozwoju Rolnictwa Ekologicznego w Polsce; IRWiR PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- Runowski, H. Organic Farming-Progress or Regress. Rocz. Nauk Rol. Ser. G 2009, 96, 4. Available online: https://sj.wne.sggw.pl/pdf/RNR_2009_n4_s182.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Berbeć, A.K.; Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Thalmann, C.; Wyss, R.; Grenz, J.; Kopiński, J.; Stalenga, J.; Radzikowski, P. Assessing the Sustainability Performance of Organic and Low-Input Conventional Farms from Eastern Poland with the RISE Indicator System. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1792.

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264.

- Röös, E.; Mie, A.; Wivstad, M.; Salomon, E.; Johansson, B.; Gunnarsson, S.; Wallenbeck, A.; Hoffmann, R.; Nilsson, U.; Sundberg, C.; et al. Risks and opportunities of increasing yields in organic farming. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 14.

- Holt-Gimenez, E.; Shattuck, A.; Altieri, M.; Herren, H.; Gliessman, S. We already grow enough food for 10 billion people…and still can’t end hunger. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 595–598.

- Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Nakielska, M.; Jończyk, K.; Berbeć, A.K.; Kopiński, J. Assessment of the Suitability of 10 Winter Tricitale Cultivars (x Triticosecale Wittm. Ex A. Camus) for organic agriculture: Polish case study. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1144.

- Alvarez, R. Comparing Productivity of Organic and Conventional Farming Systems: A Quantative Review. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 68, 1947–1958.

- De Ponti, T.; Rijk, B.; van Ittersum, M.K. The crop yield gap between organic and conventional agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2012, 108, 1–9.

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 2012, 485, 229–232.

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N. Many shades of gray-The context-dependent performance of organic agriculture. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602638.

- Kirchmann, H.; Ryan, M.H. Nutrients in organic farming—Are there advantages from the 721 exclusive use of organic manures and untreated minerals? In Proceedings of the 4th International Crop 722 Science Congress, Brisbane, Australia, 26 September–1 October 2004.

- Ziętara, W.; Mirkowska, Z. The green deal: Towards organic farming or greening of agriculture. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2021, 368, 29–54.

- Hagner, M.; Pohjanletho, I.; Nuutinen, V.; Setälä, H.; Velmala, S.; Vesterinen, E.; Pennanen, T.; Lemola, R.; Peltonniemi, K. Impacts of long-term organic production on soil fauna in boreal dairy and cereal farming. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 189, 104944.

- Sacco, D.; Moretti, B.; Monaco, S.; Grignani, C. Six-year transition from conventional to organic farming: Effects on crop production and soil quality. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 69, 10–20.

- Mayer, J.; Gunst, L.; Mäder, P.; Samson, M.; Carcea, M.; Narducci, V.; Thomsen, I.; Dubois, D. Productivity, quality and sustainability of winter wheat under long-term conventional and organic management in Switzerland. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 65, 27–39.

- Niggli, U.; Schmidt, J.; Watson Ch Kriipsalu, M.; Shanskiy, M.; Barberi, P.; Kowalska, J.; Schmitt, A.; Daniel, C.; Wenthe, U.; Conder, M.; et al. Organic Knowledge Network Arable State-of-the-Art Research Results and Best Practices. 2016. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/30506/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Jończyk, K. Aktualny stan i bariery rozwoju ekologicznej hodowli i nasiennictwa oraz znaczenie doboru odmian. Ekologiczne doświadczalnictwo odmianowe. W opracowaniu pod redakcją K. Jończyka pt. Rolnictwo ekologiczne w Polsce. Stud. Rap. IUNG-PIB Nr 2023, 70, 89–98.

- Radzikowski, P.; Jończyk, K.; Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Jóźwicki, T. Assessment of Resistance of Different Varieties of Winter Wheat to Leaf Fungal Diseases in Organic Farming. Agriculture 2023, 13, 875.

- Ponisio, C.L.; M’Gonigle, K.L.; Mace, K.C.; Palomino, J.; de Valpine, P.; Kremen, C. Diversification practices reduce organic to conventional yield gap. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20141396.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commmission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Commmittee and the Commmittee of the Regions, Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Wrzaszcz, W. Tendencies and Perspectives of Organic Farming Development in the EU—The Significance of European Green Deal Strategy. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 12, 143.

- Prandecki, K.; Wrzaszcz, W. Challenges for agriculture in Poland resulting from the implementation of the strategic objectives of the European Green Deal. Ekon. Śr.-Econ. Environ. 2022, XXIV, 109–122.

- Chmieliński, P.; Wrzaszcz, W.; Zieliński, M.; Wigier, M. Intensity and Biodiversity: The ‘Green’ Potential of Agriculture and Rural Territories in Poland in the Context of Sustainable Development. Energies 2022, 15, 2388.

- Zieliński, M.; Koza, P.; Łopatka, A. Agriculture from areas facing natural or other specific constraints (ANCs) in Poland, its characteristics, directions of changes and challenges in the context of the European Green Deal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11828.

- EC. CAP Context Indicators-2019 Update. 2019. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/performance-agricultural-policy/cap-indicators/context-indicators_en (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Jadczyszyn, J.; Zieliński, M. Assessment of farms from High Nature Value Farmland areas in Poland. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2020, 22, 108–118.

- Zieliński, M.; Jadczyszyn, J. Importance and challenges for agriculture from High Nature Value farmlands (HNVf) in Poland in the context of the provision of public goods under the European Green Deal. Ekon. Śr. Econ. Environ. 2022, 3, 194–219.

More