You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Wendy Huang and Version 1 by Sonil Nanda.

Second-generation biorefinery refers to the production of different types of biofuels, biomaterials, and biochemicals by using agri-based and other lignocellulosic biomasses as substrates, which do not compete with arable lands, water for irrigation, and food supply. From the perspective of transportation fuels, second-generation bioethanol plays a crucial role in minimizing the dependency on fossil-based fuels, especially gasoline. Significant efforts have been invested in the research and development of second-generation bioethanol for commercialization in both developing and developed countries.

- bioethanol

- biochemicals

- biofuels

- commercialization

- lignocellulosic biomass

- second-generation biorefinery

- supply chain

- pretreatment

- scaling up

1. Introduction

The global energy demand is seeing a significant escalation because of population growth and the industrial and economic progress seen in emerging nations like China and India. The current situation is characterized by growing concerns over greenhouse gas emissions, uncertainties relating to energy security, increasing fossil fuel prices, and geopolitical situations [1]. Renewable energy sources such as solar, hydro, tidal, wind, geothermal, and biomass-based energy have garnered heightened interest as potential substitutes for nonrenewable sources [2]. Nevertheless, the need for platform chemicals produced in petroleum refineries may only be substituted by renewable bioresources, namely refineries based on lignocellulosic biomass.

Lignocellulosic biorefineries are seeing a progressive global expansion whereby biomass is being used as a sustainable energy source [3]. The term lignocellulosic biorefinery pertains to a kind of biorefinery known as a second-generation biorefinery, whereby lignocellulosic biomass is used as the primary feedstock material. Lignocellulose is a plentiful and carbon-neutral bioenergy resource in comparison to conventional fossil fuels. Massive potential exists for lignocellulosic biomass to serve as a partial substitute for fossil fuels, petrochemicals, and synthetic plastics in the energy and consumer product market and meet sustainability [4]. The implementation of biorefineries offers a viable solution for the conversion of biomass into a diverse range of products, including high-value commodities and biofuels [5].

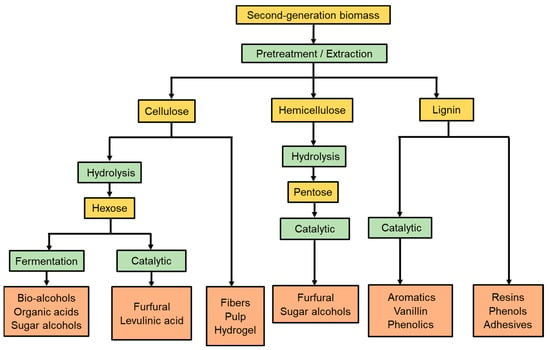

Figure 1 illustrates the many pathways involved in the production of several by-products in a second-generation biorefinery using lignocellulosic biomass. The methodological approach for the valorization of lignocellulosic biomasses to second-generation liquid biofuels, especially bioethanol, is constituted of three major steps: (i) partial disintegration of the recalcitrant moieties of the feedstock through pretreatment techniques, (ii) production of monomeric sugar hydrolysate from the fragmentation of biopolymeric matrix, and (iii) fermentation of monomeric sugars into alcohols [6]. Besides the fermentative or biochemical conversion, thermocatalytic routes can also be employed in the making of bioethanol to produce different platform chemicals like furfurals, phenolics, and levulinic acid.

Figure 1.

Bioproducts obtained from second-generation biorefinery of lignocellulosic biomass.

The predominant practice for managing lignocellulosic biomass, especially in developing countries, is direct combustion, which leads to the inefficient use of resources and air pollution [7]. Hence, the development of alternative technologies is essential to enhance the responsible usage, management, and valorization of lignocellulosic biomass [8]. The use of lignocellulose as a potential substitute is supported by its abundant and diverse sources of raw materials, as well as the advantageous market prospects of its conversion products. The primary components of biomass, including cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, play a crucial role in the biorefinery system and significantly contribute to the overall expansion of the global bioeconomy [9,10][9][10]. The generation of sugar monomers can be achieved using cellulose and hemicellulose, which are the polysaccharide constituents found in lignocellulosic biomass. The efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the bioconversion process are contingent upon the extent to which polysaccharides are effectively converted into monomeric sugars and subsequent fermentation to biofuels and biochemicals [11].

The upscaling of biochemicals and biofuel production from lignocellulosic biomass continues to pose significant problems, necessitating the resolution of many fundamental operational obstacles. The primary obstacle to the efficient use of biomass is the intricate recalcitrance and structure of lignocellulosic biomass [12,13][12][13]. The limited production of fermentable sugars could be attributed to the presence of lignin polymer and the common component of lignocellulosic feedstocks, which act as barriers to the nonspecific binding of hydrolytic enzymes [14,15,16][14][15][16]. To address these concerns, it is necessary to include lignin removal as an additional pretreatment step. This step is essential for eliminating the refractory nature of lignocellulosic biomass and facilitating its further processing [17]. Numerous pretreatment methods have been proposed over recent years to generate fermentable sugars effectively [13,18,19][13][18][19]. However, pretreatment is a costly and energy-intensive process that has a significant influence on the economic competitiveness of lignocellulosic biorefineries. The economic feasibility of the biomass market and supply chain, the level of technological advancement of the utilized technologies, and the transition from laboratory-scale to pilot-scale processes are additional significant obstacles that hinder the commercialization of lignocellulosic biorefineries [9,20][9][20].

The process of expanding biorefinery operations from a laboratory setting to a commercial scale is intricate and requires significant financial investment. Similarly, the optimization of energy efficiency and the effective management of waste by-products are imperative technical endeavors. Economic hurdles encompass several factors, such as substantial upfront investment requirements, the challenge of maintaining economic sustainability in the face of volatile oil prices, and the scarcity of available financing alternatives [21]. The prioritization of environmental sustainability and the active involvement of local communities is of utmost importance [22]. Developing countries have notable hurdles and roadblocks concerning the diversification of biomass sources, the scaling up of biorefinery technologies, and the commercialization of biofuels [23]. The restricted spectrum of biomass sources is mostly attributed to the geographical diversity of feedstocks with a heavy reliance on agricultural residues and a lack of awareness of sustainable waste management practices [24]. Addressing these obstacles and filling the gaps in knowledge is imperative to fully harness the promise of biofuels in the area and advance a sustainable, low-carbon energy trajectory.

2. Supply Chain and Availability of Second-Generation Biomass

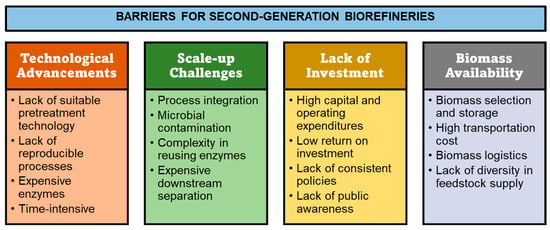

The potential obstacles for second-generation biorefinery operations are illustrated in Figure 2. Despite the higher initial investment required, biorefining proves to be a more economically efficient approach. Therefore, to ensure economic feasibility, the feedstock utilized in the biorefinery must be both cost-effective and readily accessible [19]. Various categories of second-generation biomasses can be used as feedstock, contingent upon their availability at different times throughout the year. Nevertheless, the main challenge in the commercialization of second-generation biorefineries is the consistent affordability of seasonal feedstock [83][25]. Considerable amounts of agricultural residues are generated in Asian countries such as China and India, presenting a viable opportunity for utilization as feedstock in biorefineries. According to a report by Datta et al. [84][26], India produced over 685 million metric tons of agricultural waste in 2018. However, a significant portion of this trash, up to 87 million metric tons, was disposed of by open burning on the farm, which consistently led to poor regional air quality and smog formation lingering for several days.

Figure 2.

Potential challenges in the commercialization of second-generation biorefineries.

3. Efficiency of Pretreatment and Enzymatic Saccharification

Along with the availability of biomass and the supply chain, choosing an effective pretreatment method for different feedstocks is a crucial challenge that must be taken into consideration. Biomass pretreatment is considered an essential step in the effective usage of second-generation biomass because it disintegrates the structure of biomass and separates the cellulose hemicellulose from the lignin matrix [17]. Furthermore, it improves the efficiency of the final products followed by subsequent saccharification and fermentation processes. Several physicals (e.g., extrusion and milling), physicochemical (e.g., steam explosion and ammonia fiber expansion), chemical (e.g., alkalis, acids, and ionic liquids), and biological (e.g., bacteria, fungi, and enzymes) pretreatment methods have been developed for effective biomass pretreatment and hydrolysis [13,19,20][13][19][20]. Table 1 lists the benefits and drawbacks of a few biomass pretreatment technologies. A significant problem in second-generation biomass pretreatment is the formation of high-solid loadings. Therefore, for easier processing, increased production and productivity and efficient feeding of biomass into various reactors with a high total solid concentration is crucial. Additionally, the economics of the process can be enhanced by recovering and reusing the chemicals and enzymes used in any pretreatment procedure.Table 1.

Comparison of second-generation biomass pretreatment methods.

| Methods | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological pretreatment | |||

|

|

|

|

| Chemical pretreatment | |||

|

|

|

|

| Physicochemical pretreatment | |||

|

|

|

|

4. Technology Scale-Up

The process of scaling up second-generation biorefineries to meet the increasing need for renewable energy products presents considerable challenges. In many cases, the parameters and operational conditions that have been adjusted at the laboratory scale may not exhibit the same level of efficiency when applied to demonstration-scale or pilot-scale operations [70,99][27][48]. The identification of pertinent factors for transitioning from laboratory-scale to pilot-scale, and subsequently to commercial-scale is of utmost importance. Several important factors need to be considered when scaling up biorefineries for commercialization, including the development of techno-economic models, process optimization, technological advancements, lifecycle analysis, and the simulation of cost and risk mitigation [77,104,105][28][53][54]. Furthermore, it is important to consider several other essential factors, such as minimizing waste discharge streams, limiting water consumption, efficiently utilizing resources (biomass, materials, equipment, and labor), appropriately integrating pretreatment and conversion techniques, diversifying products for the expansion of second-generation biorefineries [106][55]. The sequence of expenses in biomass management and processing involves prioritizing operational expenditures followed by capital expenditures, as the latter determines the approach for scaling up operations. To mitigate the risk of a commercial failure, it is imperative to safeguard capital expenditures and actively seek opportunities to minimize it to the greatest extent possible. One potential strategy for reducing the initial expenses involved with establishing a greenfield site is to leverage the existing infrastructure within enterprises engaged in the production of biochemicals [20]. It is also essential to consider the automation of second-generation biorefinery operations for effective commercialization. Automation can eliminate manual interventions, enhance operational efficiencies, and reduce energy use [48,95][33][44]. The implementation of second-generation bioethanol facilities in future production is imperative due to several factors. These include the substantial production costs associated with such facilities, significant political and regulatory problems surrounding their establishment, as well as the technological hazards they provide, and their limited potential returns. Besides automating the conversion processes, another major step can be taken in the commercialization of second-generation biofuels, which is the establishment of an integrated, flexible, and versatile conversion process. Unlike the “single product” biorefinery approach, the integrated biorefinery approach works in synergy to combine biological and thermochemical conversion processes to utilize resources and by-products and manage wastes to deliver multiple products. The commercialization of the integrated biorefinery process appears to be more attractive, feasible, and sustainable. For instance, in a bioethanol refinery, a major by-product is CO2 resulting from microbial metabolism, which can be reused as a non-polar solvent by converting it into supercritical CO2 fluid that can be used as an environmentally friendly extraction medium for food-grade extractions. Moreover, the major problem in a commercial bioethanol plant relies on the utilization of the residual or spent feedstock generated from the bioethanol making can be used as the feedstock for the production of carbon-rich bioproducts (e.g., biochar, hydrochar, and activated carbon) through the carbonization of the residual biomass, which can be used as a solid fuel that can be used in the distillers to for energy or can be used as a fertilizer in agriculture. This integration of the different bioconversion processes will feasibly achieve the commercial bioethanol refineries by establishing a multiproduct and zero-waste approach.References

- Nanda, S.; Mohammad, J.; Reddy, S.N.; Kozinski, J.A.; Dalai, A.K. Pathways of lignocellulosic biomass conversion to renewable fuels. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2014, 4, 157–191.

- Yao, Y.; Xu, J.H.; Sun, D.-Q. Untangling global levelised cost of electricity based on multi-factor learning curve for renewable energy: Wind, solar, geothermal, hydropower and bioenergy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124827.

- Jha, S.; Okolie, J.A.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K. A review of biomass resources and thermochemical conversion technologies. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2022, 45, 791–799.

- Mujtaba, M.; Fraceto, L.F.; Fazeli, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Savassa, S.M.; de Medeiros, G.A.; do Espírito Santo Pereira, A.; Mancini, S.D.; Lipponen, J.; Vilaplana, F. Lignocellulosic biomass from agricultural waste to the circular economy: A review with focus on biofuels, biocomposites and bioplastics. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136815.

- Forde, G.M.; Rainey, T.J.; Speight, R.; Batchelor, W.; Pattenden, L.K. Matching the biomass to the bioproduct: Summary of up-and downstream bioprocesses. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2016, 1, 20160046.

- Loow, Y.L.; Wu, T.Y.; Yang, G.H.; Jahim, J.M.; Teoh, W.H.; Mohammad, A.W. Role of energy irradiation in aiding pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for improving reducing sugar recovery. Cellulose 2016, 23, 2761–2789.

- Chai, W.S.; Bao, Y.; Jin, P.; Tang, G.; Zhou, L. A review on ammonia, ammonia-hydrogen and ammonia-methane fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111254.

- Okolie, J.A.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Kozinski, J.A. Chemistry and specialty industrial applications of lignocellulosic biomass. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2021, 12, 2145–2169.

- Patel, A.; Shah, A.R. Integrated lignocellulosic biorefinery: Gateway for production of second-generation ethanol and value-added products. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2021, 6, 108–128.

- Pattnaik, F.; Patra, B.R.; Okolie, J.A.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Naik, S. A review of thermocatalytic conversion of biogenic wastes into crude biofuels and biochemical precursors. Fuel 2022, 320, 123857.

- Yu, H.T.; Chen, B.Y.; Li, B.Y.; Tseng, M.C.; Han, C.C.; Shyu, S.G. Efficient pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass with high recovery of solid lignin and fermentable sugars using Fenton reaction in a mixed solvent. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 287.

- Okolie, J.A.; Rana, R.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Kozinski, J.A. Supercritical water gasification of biomass: A state-of-the-art review of process parameters, reaction mechanisms and catalysis. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 578–598.

- Bhatia, S.K.; Jagtap, S.S.; Bedekar, A.A.; Bhatia, R.K.; Patel, A.K.; Pant, D.; Banu, J.R.; Rao, C.V.; Kim, Y.G.; Yang, Y.H. Recent developments in pretreatment technologies on lignocellulosic biomass: Effect of key parameters, technological improvements, and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 300, 122724.

- Ponnusamy, V.K.; Nguyen, D.D.; Dharmaraja, J.; Shobana, S.; Banu, J.R.; Saratale, R.G.; Chang, S.W.; Kumar, G. A review on lignin structure, pre-treatments, fermentation reactions and biorefinery potential. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 271, 462–472.

- Zhao, C.; Qiao, X.; Shao, Q.; Hassan, M.; Ma, Z. Evolution of the lignin chemical structure during the bioethanol production process and its inhibition to enzymatic hydrolysis. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 5938–5947.

- Agrawal, R.; Verma, A.; Singhania, R.R.; Varjani, S.; Di Dong, C.; Patel, A.K. Current understanding of the inhibition factors and their mechanism of action for the lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 332, 125042.

- Mankar, A.R.; Pandey, A.; Modak, A.; Pant, K.K. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: A review on recent advances. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 334, 125235.

- Medina, J.D.C.; Woiciechowski, A.; Filho, A.Z.; Nigam, P.S.; Ramos, L.P.; Soccol, C.R. Steam explosion pretreatment of oil palm empty fruit bunches (EFB) using autocatalytic hydrolysis: A biorefinery approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 173–180.

- Cheah, W.Y.; Sankaran, R.; Show, P.L.; Ibrahim, T.N.B.T.; Chew, K.W.; Culaba, A.; Chang, J.-S. Pretreatment methods for lignocellulosic biofuels production: Current advances, challenges, and future prospects. Biofuel Res. J. 2021, 7, 1115–1127.

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Awasthi, A.K.; Lukk, T.; Tuohy, M.G.; Gong, L.; Nguyen-Tri, P.; Goddard, A.D.; Bill, R.M.; Nayak, S.C.; et al. Lignocellulosic biorefineries: The current state of challenges and strategies for efficient commercialization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111258.

- Raj, T.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Kumar, A.N.; Banu, J.R.; Yoon, J.; Bhatia, S.K.; Yang, Y.H.; Varjani, S.; Kim, S.H. Recent advances in commercial biorefineries for lignocellulosic ethanol production: Current status, challenges and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126292.

- Kothari, R.; Vashishtha, A.; Singh, H.M.; Pathak, V.V.; Tyagi, V.V.; Yadav, B.C.; Ashokkumar, V.; Singh, D.P. Assessment of Indian bioenergy policy for sustainable environment and its impact for rural India: Strategic implementation and challenges. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101078.

- Velankar, H.R.; Thulluri, C.; Mattam, A.J. Development of second-generation ethanol technologies in India: Current status of commercialization. In Advanced Biofuel Technologies; Tuli, D., Kasture, S., Kuila, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 135–149.

- Sharma, A.; Srikavya, B.P.; Urade, A.D.; Joshi, A.; Narain, R.S.; Dwarakanath, V.; Alam, T.; Prasad, R.S. Economic and environmental impacts of biofuels in Indian context. Mater. Today Proc. 2023.

- Karp, S.G.; Schmitt, C.C.; Moreira, R.; Penha, R.O.; Murawski de Mello, A.F.; Herrmann, L.W.; Soccol, C.R. Sugarcane biorefineries: Status and perspectives in bioeconomy. Bio Energy Res. 2022, 15, 1842–1853.

- Datta, A.; Emmanuel, M.A.; Ram, N.K.; Dhingra, S. Crop Residue Management: Solution to Achieve Better Air Quality. Available online: https://www.teriin.org/policy-brief/crop-residue-management-solution-achieve-better-air-quality (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Chandel, A.K.; Garlapati, V.K.; Singh, A.K.; Antunes, F.A.F.; da Silva, S.S. The path forward for lignocellulose biorefineries: Bottlenecks, solutions, and perspective on commercialization. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 264, 370–381.

- Kumar, B.; Verma, P. Biomass-based biorefineries: An important architype towards a circular economy. Fuel 2021, 288, 119622.

- Junqueira, T.L.; Cavalett, O.; Bonomi, A. The virtual sugarcane biorefinery-a simulation tool to support public policies formulation in bioenergy. Ind. Biotechnol. 2016, 12, 62–67.

- Bhowmick, G.D.; Sarmah, A.K.; Sen, R. Lignocellulosic biorefinery as a model for sustainable development of biofuels and value added products. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1144–1154.

- Sarker, T.R.; Nanda, S.; Meda, V.; Dalai, A.K. Densification of waste biomass for manufacturing solid biofuel pellets: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 231–264.

- Nunes, L.; Causer, T.; Ciolkosz, D. Biomass for energy: A review on supply chain management models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109658.

- Singh, N.; Singhania, R.R.; Nigam, P.S.; Dong, C.D.; Patel, A.K.; Puri, M. Global status of lignocellulosic biorefinery: Challenges and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126415.

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Singh, S.; Cheng, G. Transforming lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels enabled by ionic liquid pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 322, 124522.

- Hoang, A.T.; Nizetic, S.; Ong, H.C.; Chong, C.T.; Atabani, A.E.; Pham, V.V. Acid-based lignocellulosic biomass biorefinery for bioenergy production: Advantages, application constraints, and perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113194.

- Yoo, C.G.; Meng, X.; Pu, Y.; Ragauskas, A.J. The critical role of lignin in lignocellulosic biomass conversion and recent pretreatment strategies: A comprehensive review. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122784.

- Hassan, S.S.; Williams, G.A.; Jaiswal, A.K. Moving towards the second generation of lignocellulosic biorefineries in the EU: Drivers, challenges, and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 590–599.

- Yuan, Y.; Jiang, B.; Chen, H.; Ww, S.; Jin, Y.; Xiao, H. Recent advances in understanding the effects of lignin structural characteristics on enzymatic hydrolysis. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 205.

- Huang, C.; Jiang, X.; Shen, X.; Hu, J.; Tang, W.; Wu, X.; Ragauskas, A.; Jameel, H.; Meng, X.; Yong, Q. Lignin-enzyme interaction: A roadblock for efficient enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111822.

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial fermentation: The most favorable biotechnological methods for the release of bioactive peptides. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2021, 3, 100047.

- Islam, M.K.; Wang, H.; Rehman, S.; Dong, C.; Hsu, H.Y.; Lin, C.S.K.; Leu, S.Y. Sustainability metrics of pretreatment processes in a waste derived lignocellulosic biomass biorefinery. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122558.

- Saini, J.K.; Singhania, R.R.; Satlewal, A.; Saini, R.; Gupta, R.; Tuli, D.; Mathur, A.; Adsul, M. Improvement of wheat straw hydrolysis by cellulolytic blends of two Penicillium spp. Renew. Energy 2016, 98, 43–50.

- Saini, J.K.; Patel, A.K.; Adsul, M.; Singhania, R.R. Cellulase adsorption on lignin: A roadblock for economic hydrolysis of biomass. Renew. Energy 2016, 98, 29–42.

- Ubando, A.T.; Felix, C.B.; Chen, W.H. Biorefineries in circular bioeconomy: A comprehensive review. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 299, 122585.

- Adsul, M.; Sandhu, S.K.; Singhania, R.R.; Gupta, R.; Puri, S.K.; Mathur, A. Designing a cellulolytic enzyme cocktail for the efficient and economical conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to biofuels. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2020, 133, 109442.

- Singhania, R.R.; Sukumaran, R.K.; Patel, A.K.; Larroche, C.; Pandey, A. Advancement and comparative profiles in the production technologies using solid-state and submerged fermentation for microbial cellulases. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2010, 46, 541–549.

- Saini, R.; Saini, J.K.; Adsul, M.; Patel, A.K.; Mathur, A.; Tuli, D.K.; Singhania, R.R. Enhanced cellulase production by Penicillium oxalicum for bioethanol application. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 188, 240–246.

- Singhania, R.R.; Ruiz, H.A.; Awasthi, M.K.; Dong, C.-D.; Chen, C.-W.; Patel, A.K. Challenges in cellulase bioprocess for biofuel applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111622.

- Siqueira, J.G.W.; Rodrigues, C.; Vandenberghe, L.P.D.S.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soccol, C.R. Current advances in on-site cellulase production and application on lignocellulosic biomass conversion to biofuels: A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 132, 105419.

- Karnaouri, A.; Antonopoulou, I.; Zerva, A.; Dimarogona, M.; Topakas, E.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. Thermophilic enzyme systems for efficient conversion of lignocellulose to valuable products: Structural insights and future perspectives for esterases and oxidative catalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 279, 362–372.

- Han, J.; Cao, R.; Zhou, X.; Xu, Y. An integrated biorefinery process for adding values to corncob in co-production of xylooligosaccharides and glucose starting from pretreatment with gluconic acid. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123200.

- Xia, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Tan, Z.; He, S.; Zhu, X.; Shi, H.; Liu, P.; Bilal, M.; et al. Improved lignocellulose degradation efficiency by fusion of beta-glucosidase, exoglucanase, and carbohydrate-binding module from Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Bioresources 2019, 14, 6767–6780.

- Nizami, A.S.; Rehan, M.; Waqas, M.; Naqvi, M.; Ouda, O.K.M.; Shahzad, K.; Miandad, R.; Khan, M.Z.; Syamsiro, M.; Ismail, I.M.I.; et al. Waste biorefineries: Enabling circular economies in developing countries. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 1101–1117.

- Sharma, B.; Larroche, C.; Dussap, C.G. Comprehensive assessment of second-generation bioethanol production. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 313, 123630.

- Oh, Y.K.; Hwang, K.R.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.R.; Lee, J.S. Recent developments and key barriers to advanced biofuels: A short review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 257, 320–333.

More