Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Maria Theodoratou and Version 2 by Mona Zou.

Coping strategies, the cognitive and behavioral responses to stress, were first systematically described by Lazarus and Folkman. Early psychoanalytic work established the foundation for this concept, which was later refined by empirical studies by theorists such as Pearlin and others. Lazarus articulated coping as a dynamic transaction involving cognitive, behavioral, and emotional adjustments to stress. Folkman extended this by introducing meaning-focused coping to complement the problem- and emotion-focused paradigms.

- coping strategies

- neuropsychology

- interventions

- stress pathways

- clinical settings

1. Introduction

Coping strategies, the cognitive and behavioral responses to stress, were first systematically described by Lazarus and Folkman [1]. Early psychoanalytic work established the foundation for this concept, which was later refined by empirical studies by theorists such as Pearlin and others [2][3][4][5][6][7][2,3,4,5,6,7]. Lazarus articulated coping as a dynamic transaction involving cognitive, behavioral, and emotional adjustments to stress [1][8][1,8]. Folkman extended this by introducing meaning-focused coping to complement the problem- and emotion-focused paradigms [9]. This body of research has had a significant impact on clinical and neuropsychology, underpinning methods to enhance adaptability and resilience [10][11][12][13][10,11,12,13]. Such strategies have been shown to be effective in improving outcomes in a variety of professional settings [14][15][14,15] and are particularly important for populations with special mental health needs [16]. Coping strategies span individual, interpersonal, and institutional dimensions, each of which is integral to resilience and stress management [17]. At the individual level, techniques such as cognitive reappraisal and action-oriented coping effectively reduce anxiety and improve wellbeing [18]. Interpersonally, the support of relationships and social networks is essential and has been consistently shown to benefit mental health [14]. Institutionally, organizational policies and initiatives promote mental health through access to resources and supportive work environments [19]. Within the field of mental health, clinical psychology and neuropsychology continue to innovate coping strategies for diverse populations. Clinical psychology, which focuses on psychological assessment and intervention, uses developmental and cognitive research to address mental health challenges and promote wellbeing [20][21][22][20,21,22]. Neuropsychology links brain structure and function to behavior and mental processes to inform interventions [23][24][25][23,24,25].2. Coping Strategies in Neuropsychology: A Multifaceted Exploration

2.1. Stress Mechanisms and Coping

Coping strategies’ effectiveness is inherently tied to individual and situational factors, with neuropsychological functions like memory and concentration significantly impacting their use [26][27][28][29][30][31][45,46,47,48,49,50]. Neuropsychology focuses on understanding how brain functions influence cognitive abilities and stress responses [32][51]. Stress triggers a biologically hardwired spectrum of responses that are shaped by evolutionary adaptations, with the brain playing a pivotal role in modulating these responses through stress appraisal [33][52].

Effective stress management hinges on executive functions that are crucial for decision making and planning, which are linked to stress appraisal and coping strategy selection. Strong executive functions suggest better stress management capabilities, contributing to cognitive resilience and life satisfaction [34][35][36][53,54,55]. Key brain regions, including the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex, coordinate stress perception and response, while chronic stress may lead to allostatic overload, affecting brain resilience and emotional regulation [37][38][39][40][41][56,57,58,59,60].

The interplay of oxytocin and vasopressin with human behavior, particularly with regard to stress and coping, is scientifically significant [42][43][44][61,62,63]. Oxytocin, known for its prosocial effects, can enhance social support and attenuate stress-related markers such as cortisol, while also influencing reward-related behaviors [45][46][47][64,65,66]. Research on oxytocin receptors, their dietary modulation, and the genetic and epigenetic factors underlying attachment and trauma are informing variability in stress resilience and psychopathology. These findings are critical to the development of personalized treatment strategies in the domains of the brain, psychological, and psychiatric sciences, including cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety, which may interact with these neuropeptide pathways [48][49][50][67,68,69].

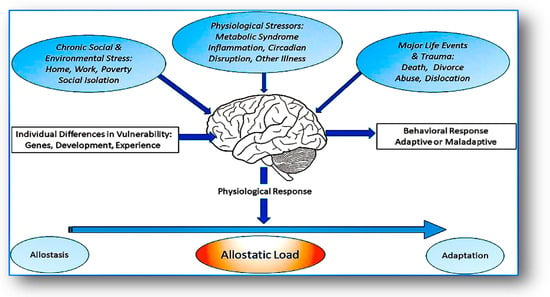

Allostasis, the body’s process of maintaining stability through physiological adaptations, is extremely important under stress [51][70]. Short-term stress responses can be beneficial for survival [52][53][71,72], but prolonged stress can lead to an “allostatic overload” that negatively impacts physical and mental health [Figure 12] Recent research is moving beyond physical effects to explore the neurobiological basis of psychological resilience and the development of stress-related disorders such as PTSD and depression. A better understanding of the neurochemical survival responses and the neural regulation of emotion, memory, and social behavior under extreme stress may revolutionize the prevention and treatment of these conditions, as well as inform the most psychologically beneficial coping strategies [54][73].

Figure 12. Allostatic load and its impact: the role of the brain and limbic regions in stress response and disease progression. Adapted from McEwen, B.S.; Akil, H. Revisiting the Stress Concept: Implications for Affective Disorders. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0733-19.2019.

Neuropsychological research examines how neuropeptides such as oxytocin and vasopressin affect brain function and behavior, particularly in relation to stress and coping mechanisms. Imbalances in these systems may contribute to conditions such as depression and anxiety, which alter coping strategies. Consequently, therapies targeting these neuropeptide systems are being investigated as treatments for stress-related disorders [55][56][74,75].

For example, intranasal oxytocin is being investigated for its potential to improve social cognition and coping in conditions such as autism and social anxiety. Vasopressin, while sharing some roles with oxytocin in social behavior, primarily modulates coping by enhancing threat preparedness, influencing the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, and affecting social behaviors ranging from bonding to aggression [57][58][76,77].

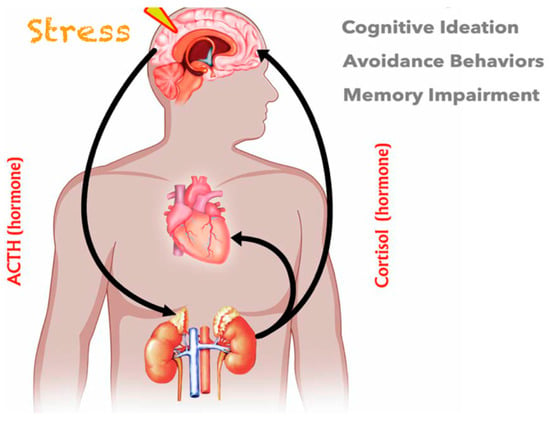

Vasopressin can promote the fight or flight response, aiding in acute stress management, but excessive activation can lead to chronic stress and related health problems. This highlights the fine line between adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms. In addition, cognitive processes play a central role in assessing threats and directing behavioral responses, while the pituitary and adrenal systems, including cortisol, regulate long-term stress and restore equilibrium [59][60][61][62][78,79,80,81].

A vasopressin imbalance is associated with social dysfunction and increased stress in neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacological targeting of vasopressin receptors may help reduce maladaptive stress responses and improve social functioning in these conditions [63][64][65][82,83,84]. The balance of vasopressin actions is critical for both immediate survival and long-term mental and social wellbeing.

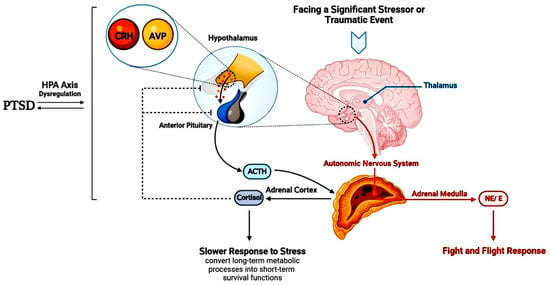

Stressful events activate the sympathetic–adrenal–medullary (SAM) and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axes, with regulation by the amygdala and prefrontal cortex [Figure 23]. The amygdala initiates immediate stress responses, while the prefrontal cortex manages longer-term evaluations and influences the activities of the SAM and HPA axes [Figure 34]. The SAM axis rapidly triggers physical fight or flight responses, while the HPA axis has a slower response, releasing hormones such as cortisol that regulate themselves through a feedback loop [66][67][68][85,86,87].

Figure 23. Responses to stress. Adapted from Raise-Abdullahi, P.; Meamar, M.; Vafaei, A.A.; Alizadeh, M.; Dadkhah, M.; Shafia, S.; Ghalandari-Shamami, M.; Naderian, R.; Afshin Samaei, S.; Rashidy-Pour, A. Hypothalamus and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Review. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13071010.

Figure 34. HPA axis’s role in stress and coping. Adapted from Hinds, J.A.; Sanchez, E.R. The Role of the Hypothalamus–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) Axis in Test-Induced Anxiety: Assessments, Physiological Responses, and Molecular Details. Stresses 2022, 2, 146–155. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses2010011.

The specificity of the HPA and SAM axes in responding to and recovering from stress underlies the need to consider stressor characteristics when assessing the impact of stress biology on resilience and vulnerability [69][70][88,89]. A neuropsychological perspective on these axes may inform effective coping strategies to enhance resilience to stress-related disorders [71][90].

2.2. Coping Strategies via the Neuropsychological Approach

Cognitive Coping Strategies

The following coping mechanisms have gained prominence in neuropsychological research and practice:

-

Distraction shifts the focus away from stressors, affecting working memory and attentional systems. It includes simple, accessible methods such as engaging with nature, movies, music, tactile activities, smells, and tastes to provide immediate sensory relief and present moment awareness [76][77][95,96].

-

Mental and physical distraction: Focusing on constructive tasks such as counting, visualizing, writing, and reminiscing can draw attention away from anxiety [78][97[79],98]. Physical activities such as dancing, walking, or doing housework not only provide distraction but also improve the environment, providing both immediate and lasting therapeutic effects [80][99].

-

Physical exercise: Recognized for its behavioral and mental health benefits, exercise also acts as a neuropsychological intervention [81][82][100,101]. It stimulates brain regions that are involved in memory and learning, and the release of endorphins after exercise improves one’s mood, linking physical and cognitive wellbeing [83][84][85][102,103,104].

-

Mindfulness: This practice is increasingly recognized in neuropsychology for its effects on brain regions that are associated with attention and awareness [85][104]. By anchoring awareness in the present, mindfulness provides relief from repetitive negative thoughts and can improve coping with mental health problems [86][105]. These strategies demonstrate how targeted activities can engage the brain’s neuroplasticity and cognitive resources to counter stress and improve mental health.

Emotional Coping Strategies

Carver and colleagues (1989) defined emotion-focused coping as including strategies such as seeking emotional support, expressing and regulating emotions, disengagement, reframing, denial, acceptance, religious involvement, and substance abstinence [87][106]. Emotion-focused coping strategies are frequently employed, with research indicating distinct gender-based preferences: women tend to prioritize seeking emotional support, whereas men more commonly resort to direct problem-solving approaches to manage stress [88][89][107,108]. Social support not only provides comfort but also has physiological benefits, helping to dampen stress responses and influencing brain regions that are associated with emotion regulation [90][91][109,110].

Coping strategies range from adaptive, which promote resilience and neural adaptability, to maladaptive, such as avoidance, which may temporarily reduce stress but may lead to increased distress over time [92][93][94][111,112,113]. Adaptive strategies are associated with positive neural patterns, while maladaptive strategies may increase the brain’s stress pathways, which may affect long-term mental health.

3. Coping in Clinical Conditions

3.1. Coping with Chronic Pain

Neuropsychology links chronic pain to the functioning of brain areas like the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and prefrontal cortex, which influence both the physical sensation of pain and its cognitive and emotional aspects [95][114]. Chronic pain is not just a physical sensation; it is deeply connected to cognitive and emotional states, which are influenced by these regions [96][115]. Understanding the role of these areas can offer insights into how interventions might impact pain perception [97][116]. For instance, the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in decision making and emotional regulation, might be a target for strategies aiming to reshape one’s relationship with pain. By tapping into the neural substrates of pain, neuropsychological research paves the way for more effective, brain-based interventions that not only manage pain but also enhance the lives of those living with chronic pain [98][117].

Coping with pain, clinical psychological interventions primarily focus on cognitive, behavioral, and mindfulness strategies to improve the understanding of pain, reduce its psychological impact, and increase functional capacity despite its presence [99][118]. A crucial component of these strategies is psychoeducation, which empowers patients by providing knowledge about the nature and mechanisms of chronic pain, fostering better self-management [100][101][119,120].

While both CBT and ACT employ distinct techniques, their overarching aim is to cultivate understanding and promote behavioral change. While CBT emphasizes the transformation of maladaptive thought patterns, ACT focuses on their acceptance and the pursuit of actions that resonate with personal values [102][121].

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) emphasizes the role of cognitive processes in determining our emotional responses and behaviors [103][122]. It operates on the principle that changing maladaptive thought patterns can lead to changes in behavior and emotional responses, thereby providing tools and techniques for patients to better cope with stressors.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is rooted in the belief that the interplay between our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors dictates our mental wellbeing [104][123]. In essence, how we think about a situation affects our emotional response, which then influences our resulting behavior. One of the central techniques in CBT is cognitive restructuring [105][106][107][124,125,126]. Through this process, individuals identify and challenge negative thought patterns, replacing them with more positive or realistic ones. Behavioral activation, especially relevant for depression, introduces activities step by step to counteract the inertia that is often seen in depressed individuals [108][127]. For anxiety disorders, exposure therapy is commonly used, systematically exposing individuals to their feared stimuli or situations in a controlled setting [109][128]. Beyond these, CBT can also involve training in specific skills, such as communication or assertiveness, to enhance coping.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), on the other hand, merges traditional behavior therapy techniques with mindfulness strategies. Its primary goal is psychological flexibility, which encourages individuals to remain open, adaptable, and effective, even when faced with unwanted thoughts or emotions [110][129]. A key principle of ACT is cognitive defusion, where individuals are taught to view their thoughts as mere words rather than taking them as literal truths. For instance, rather than accepting the thought “I’m a failure” as an inherent truth, one learns to see it as just a collection of words. Acceptance, another cornerstone of ACT, involves letting thoughts, feelings, and memories flow without resistance. Paired with this is mindfulness, promoting a nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment. Central to ACT is the process of value clarification, helping individuals discern their core values in life. This understanding then guides the committed action, where individuals set and pursue goals aligned with their identified values, regardless of the personal challenges that they might face.

Additionally, it is worth noting the relevance of other therapeutic approaches such as Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) and Self-Management. PST focuses on helping individuals develop strategies to directly address and resolve the problems causing them stress, promoting proactive coping [111][130]. Self-Management, meanwhile, equips individuals with skills and strategies to manage their symptoms, behaviors, and overall wellbeing, making it a valuable tool in the context of chronic illnesses or long-term conditions [112][131].

Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) is rooted in clinical psychology and serves as a bridge to understanding how individuals interpret and act upon challenges in their environment [113][132]. It targets problem solving deficits to reduce psychological distress. PST enhances an individual’s ability to identify and correct maladaptive cognitive patterns, thereby building resilience and contributing to long-term mental health. The therapy aids individuals in recognizing problematic cognitive patterns, understanding their causes and effects, and subsequently developing adaptive strategies. By enhancing problem solving skills, PST not only addresses immediate issues but also fortifies the individual’s resilience, a pivotal aspect in clinical psychology’s goal of long-term mental wellbeing.

Self-Management, while rooted in clinical psychology, has significant overlaps with neuropsychology, especially when addressing conditions with neurological underpinnings. Self-management strategies empower individuals, particularly those with neurological conditions or cognitive impairments, to actively participate in managing their health and cognitive functions [114][115][133,134]. For instance, someone with a traumatic brain injury might employ self-management techniques to understand their cognitive limitations, develop compensatory strategies, and optimize their daily functioning. Emotional self-regulation, a cornerstone of self-management, is also of keen interest in both clinical psychology and neuropsychology, highlighting the intricate interplay between emotional processing regions in the brain and one’s psychological state. By fostering a proactive attitude towards health and cognition, individuals can significantly improve their quality of life, reflecting the shared objectives of both clinical psychology and neuropsychology.

Interestingly, addressing pain catastrophizing can prevent individuals from amplifying the threat of pain [116][117][135,136], while group therapy offers a supportive community to share experiences and coping techniques [118][119][137,138]. For those fearful of movement due to pain, graded exposure gradually reintroduces activity, ensuring that patients remain active and engaged in their daily lives [120][139].

3.2. Coping in Neurodegenerative Diseases

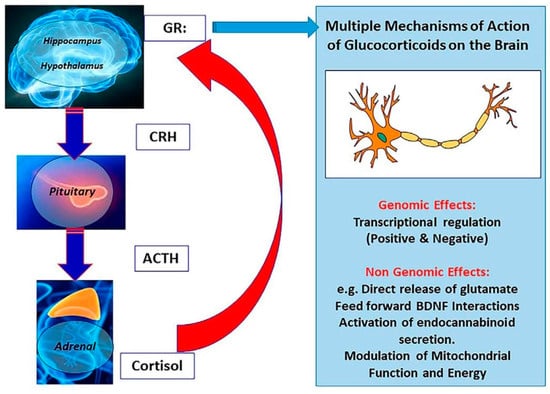

Neurodegenerative diseases, particularly conditions like Alzheimer’s Disease, lead to profound cognitive and emotional challenges that significantly impact daily life. Patients grappling with these diseases often resort to various coping strategies to navigate and adapt to the evolving landscape of their condition [121][140]. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, understanding coping mechanisms requires a neuropsychological understanding of stress responses, particularly those involving the HPA axis [122][141]. Chronic stress leads to continuous glucocorticoid release [Figure 45]. This process can damage hippocampal neurons that are critical for memory and exacerbate cognitive decline, increasing susceptibility to diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Prolonged stress also disrupts cortisol receptors, causing cognitive and mood problems that are characteristic of neurodegeneration. These findings underscore the importance of stress management in the trajectories and coping strategies of neurodegenerative diseases.

Figure 45. Limbic HPA axis regulation: the feedback role of glucocorticoids in stress response modulation. Adapted from McEwen, B.S.; Akil, H. Revisiting the Stress Concept: Implications for Affective Disorders. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0733-19.2019.

Stress triggers the HPA axis to release cortisol, which is beneficial in the short term but harmful with prolonged exposure, damaging memory-related hippocampal neurons and increasing Alzheimer’s risk. Chronic stress also impairs cortisol-regulating brain receptors, leading to cognitive deficits and mood issues that are seen in neurodegenerative diseases [123][124][125][126][127][128][142,143,144,145,146,147]. In the face of stress, the brain employs coping mechanisms as a form of defense. When such approaches induce the desired effects, they help modulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and normalize cortisol levels. Regulating the HPA is particularly important for protecting regions such as the hippocampus from potential damage [129][148].

Certain coping techniques, encompassing mindfulness and cognitive behavioral approaches, fortify neuroplasticity, enabling the brain to counteract the effects of stress [130][149].

Moreover, physical activity leads to the secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports the health of nerve cells and stimulates the formation of new brain cells, thereby enhancing cognitive functions. [131][150]. Beyond this, adaptive coping reduces oxidative stress, a known contributor to neuronal damage [132][151]. Coping also strengthens the prefrontal cortex (PFC), empowering it to modulate the emotional responses that are triggered by the amygdala [133][152]. Techniques that emphasize cognitive control, such as reframing thoughts or practicing mindfulness, amplify the PFC’s balancing influence.

On a holistic level, coping mechanisms, when applied effectively, engage multiple neurological pathways to counter the detrimental impacts of chronic stress. By fostering resilience and maintaining neurochemical equilibrium, they provide a shield against potential brain damage, underscoring the value of mental and emotional self-care in neuroprotection [134][153]. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, these coping mechanisms extend to the use of methods, such as memory aids and environmental modifications. In rehabilitation, particularly following neurological or mental health setbacks, coping strategies play a pivotal role. Beyond the primary goal of regaining lost functions after a brain injury, individuals face the profound challenge of reestablishing their identity. Here, strategies such as mindfulness and cognitive restructuring become indispensable tools for adjustment. Similarly, in mental health rehabilitation, the objective is not merely symptom management but also rebuilding an individual’s rapport with themselves and their environment.

Therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) help rectify maladaptive cognitive patterns [135][154], while Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) fosters present-focused awareness [136][155]. Employing these strategies not only simplifies the recovery journey but also instills a sense of agency, guiding individuals towards psychological balance.

By studying these coping mechanisms through the lens of neuropsychology, re-searchers can understand not just the behaviors themselves but the underlying neural mechanisms that make them effective or ineffective. This understanding can then be applied in clinical settings to improve mental health treatment and outcomes.