Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lindsay Dong and Version 1 by Sharon J. Nieter Burgmayer.

The pyranopterin dithiolene ligand is remarkable in terms of its geometric and electronic structure and is uniquely found in mononuclear molybdenum and tungsten enzymes. The pyranopterin dithiolene is found coordinated to the metal ion, deeply buried within the protein, and non-covalently attached to the protein via an extensive hydrogen bonding network that is enzyme-specific. However, the function of pyranopterin dithiolene in enzymatic catalysis has been difficult to determine. This focused account aims to provide an overview of what has been learned from the study of pyranopterin dithiolene model complexes of molybdenum and how these results relate to the enzyme systems.

- molybdenum enzymes

- pyranopterin

- molybdopterin

- dithiolene

1. Introduction

The pyranopterin molybdenum (Mo) enzymes factor prominently in global biogeochemical cycles and are critical to the life processes of most organisms on Earth [1,2,3,4,5,6,7][1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. In humans, these enzymes catalyze reactions that contribute to the production of reactive oxygen species associated with postischemic reperfusion injury [8,9][8][9] and oxidative stress [10], xenobiotic detoxification [10[10][11][12][13][14][15][16],11,12,13,14,15,16], drug metabolism [11,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24][11][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24] and prodrug activation [21[21][25],25], nitrite to NO conversion [24,26,27,28,29,30,31[24][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33],32,33], sulfite oxidation [1,34,35,36][1][34][35][36], molybdenum cofactor (Moco) sulfuration [26[26][33][37][38][39][40][41][42],33,37,38,39,40,41,42], and amino acid catabolism [43]. The importance of these enzymes in humans is underscored by the fact that Moco deficiency can result in early infant mortality [24]. More recently, pyranopterin Mo enzymes have been found to play key roles in the gut microbiome [17,44,45,46][17][44][45][46] and as methionine sulfoxide reductases in respiratory pathogens (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae) [1,47,48,49,50][1][47][48][49][50]. These are unusual metalloenzymes since they employ second- (Mo) and third-row (W) transition metal ions to perform a myriad of two-electron redox transformations [4]. Furthermore, Moco in these molybdoenzymes is unique in possessing a pyranopterin dithiolene ligand (PDT; also known as molybdopterin) [37[37][51][52][53][54][55][56],51,52,53,54,55,56], and Moco is biosynthesized in a complex series of reactions by nine different gene products in bacteria and seven in plants and humans [37,39,54,55,56,57,58,59,60][37][39][54][55][56][57][58][59][60]. The related pyranopterin W enzymes possess a closely analogous cofactor, the tungsten cofactor, or Tuco [3,61,62][3][61][62].

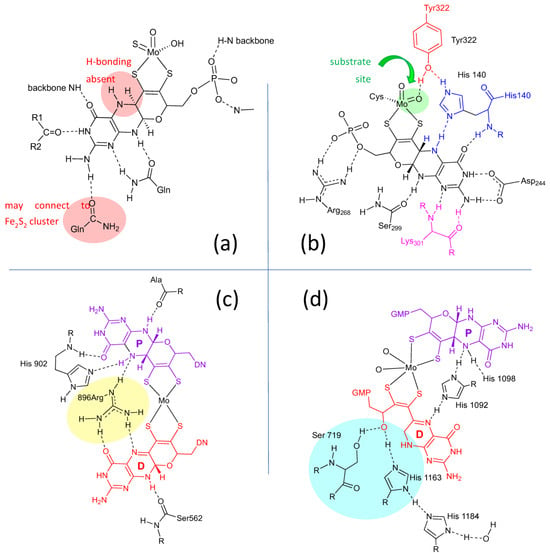

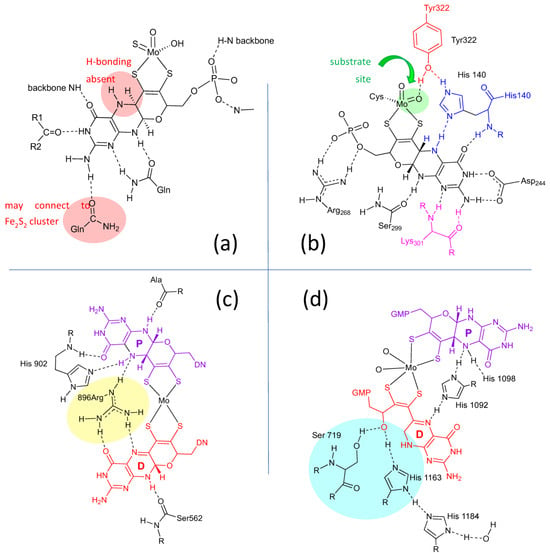

Figure 43. H-bonding interactions between the pyranopterin of Moco and adjacent protein residues. (a) Conserved H-bonding interactions identified for all 7 members of the XDH family. (b) Conserved H-bonding interactions identified for three members of the SUOX family. (c) H-bonding interactions within the DMSOR protein structure that are representative of 15 other members of the DMSOR family. (d) H-bonding interaction in E. coli nitrate reductase, whose Moco exhibits one non-cyclized pterin structure.

Figure 43. H-bonding interactions between the pyranopterin of Moco and adjacent protein residues. (a) Conserved H-bonding interactions identified for all 7 members of the XDH family. (b) Conserved H-bonding interactions identified for three members of the SUOX family. (c) H-bonding interactions within the DMSOR protein structure that are representative of 15 other members of the DMSOR family. (d) H-bonding interaction in E. coli nitrate reductase, whose Moco exhibits one non-cyclized pterin structure.

2. Currently Known about Moco in the Enzymes

2.1. Protein X-ray Crystallography Gives Atomic Level Views of Moco

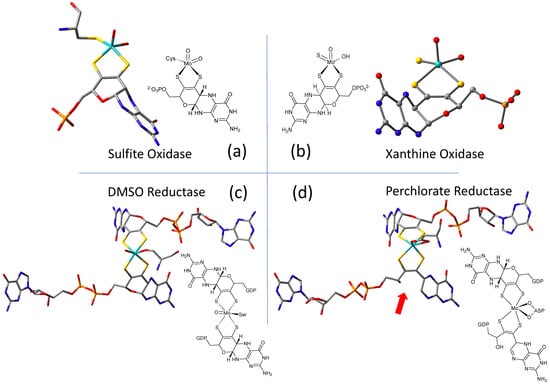

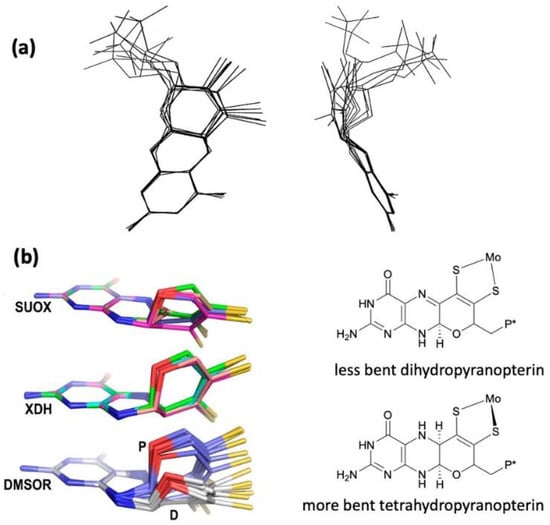

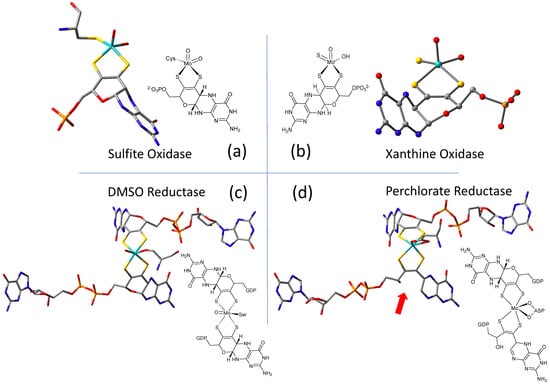

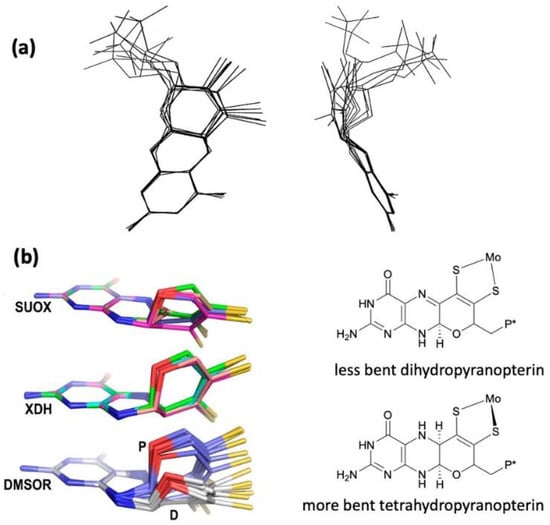

The W-containing aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase [76][63] and Mo dimethylsulfoxide reductase DMSOR(DMSOR) [77][64] were structurally characterized in 1995 and 1996, respectively, and the structures represent the first for any pyranopterin tungsten or molybdenum enzyme. Now there are crystal structures for a large number of molybdoenzymes, and this has led to a dramatic increase in our understanding of these enzymes. Figure 21 shows Moco as found in each of the three canonical molybdoenzyme families: sulfite oxidase (SUOX), xanthine oxidase (XDH), and dimethylsulfoxide reductase (DMSOR). These structures are depicted both as a three-dimensional image and in a bond line drawing representation. The 3D views emphasize the non-planar, bent nature of the pyranopterin component of Moco. As more examples of Moco structures located in different protein environments became available through protein crystallography, the dramatic range of pyranopterin conformations within the PDT ligand became apparent. This flexibility in pyranopterin conformation was noted as early as 1997 [78][65], and it is depicted as an overlay of the pyranopterin portions of Moco from different protein crystal structures (Figure 3a2). A more recent analysis of the metrical differences in the folding of 319 pyranopterins in 102 molybdenum protein structures led to the identification of two main pyranopterin conformations observed in the protein structures and to the proposal that the pterin might have different oxidation states among the three families (Figure 3b2) [79][66]. From the work emerged the proposal that the highly bent PDT ligands displayed in the XDH family enzymes corresponded to fully reduced pyranopterin structures, whereas the less bent pyranopterins in the PDTs from SUOX family proteins better fit a dihydropyranopterin structure (Figure 3b2). Intriguingly, the two PDT pyranopterins in the DMSOR family of proteins exhibited different conformations, where the highly bent proximal pyranopterin fits a reduced pyranopterin description while the distal PDT ligand is less bent and consistent with a dihydropterin assignment.

Figure 21. Representative examples of Moco structures for each of the SO, XO, and DMSO families, and one example of Moco possessing one PDT having an open, uncyclized pyran ligand. (a) Sulfite Oxidase (PDB 1SOX). (b) Xanthine Oxidase (PDB 3NRZ). (c) Dimethylsulfoxide Reductase (PDB 1EU1). (d) Perchlorate Reductase (PDB 5CH7) where the red arrow points to the open pyran ring position.

Figure 32. (a) Two views of the range of pyranopterin conformations observed in 1997. (b) Two distinct conformations suggest that pyranopterins in Moco have different oxidation states in different families. P* denotes a phosphate or a dinucleotide terminus. Adapted from Ref. [79][66].

A second type of structural anomaly is observed within the pyranopterin portion of Moco. Among the large number of molybdoenzyme structures, there are three proteins—all members of the DMSOR family—whose structures clearly show the distal PDT ligand with no pyran ring [80][67]. The first such example identified was dissimilatory nitrate reductase (NarGHI) from E. coli [81][68], followed by ethyl benzene dehydrogenase (EBDH) [82][69]. The most recent example is perchlorate reductase (PcrAB) [83][70] from Azospira suillum, which is shown as a representative example for this structural type in Figure 21d.

Lastly, the protein environment that encapsulates and protects Moco from degradation is recognized to play a role in Moco function. The abundance of H-bonds tethering pyranopterin to the protein is recognized to enforce the proper orientation and conformation of the cofactor. However, H-bonding analysis shows several other ways that H-bonds—or indeed, their absence—might be involved in catalysis. A study of all known PDT-containing protein structures that analyzed patterns of hydrogen bonding interactions between protein residues and Moco revealed multiple conserved features within each protein family [80][67]. These are summarized pictorially in Figure 43.

2.2. Information about the PDT of Moco Obtained from Spectroscopy

Direct spectroscopic studies that inform on the PDT component of Moco are sparse [89[71][72],90], and this is due to the fact that the vast majority of pyranopterin Mo enzymes possess additional highly absorbing chromophores, including flavin, [2Fe-2S], [4Fe-4S], and heme. However, spectroscopic probes of the PDT in molybdoproteins that lack these chromophores and in relevant model systems that possess a coordinated PDT ligand are important, and these studies will assist in defining both the proposed and still unknown role(s) of the PDT in catalysis. As detailed in the prior section, the PDT has no covalent interactions with the protein, and X-ray crystallography provides strong evidence that the PDT is extensively hydrogen bonded to the protein [80][67].

Early resonance Raman spectroscopic studies were performed on R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus DMSORs [93,94,95][73][74][75] and biotin sulfoxide reductase [96][76], but more direct probes of hydrogen bonding between the protein and the pyranopterin derive from Raman studies on bovine and bacterial XO/XDH [89,90,97,98][71][72][77][78]. These latter studies have been particularly revealing from the standpoint of observing low-frequency modes assignable to the PDT. Using lumazine as the reducing substrate, it has been shown that XO/XDH catalyzes the two-electron conversion of this substrate to violopterin [89,90,97,98,99,100[71][72][77][78][79][80][81][82],101,102], which subsequently binds strongly to the Mo(IV) center, allowing for spectral probing of an enzyme-product complex by optical spectroscopies. This Mo(IV)-violopterin state possesses an intense charge transfer band that absorbs light in the red/NIR region of the optical spectrum, providing an opportunity to probe a catalytically relevant product-bound species formed by enzymatic turnover by optically pumping into this band and probing the nature of resonantly enhanced protein and product vibrations. The importance of this band being in the red/NIR region of the spectrum is underscored by the fact that spectral contributions from both the [2Fe-2S] clusters and FAD are effectively eliminated, and this includes any notable background fluorescence from the FAD. The early resonance Raman studies by Hille and coworkers [98][78], which indicated that the low-energy charge transfer band was Mo → violapterin in nature, showed that numerous vibrational modes associated with the violopterin product were observed. The lower frequency vibrations in the 250–1100 cm−1 region were postulated to arise from the Mo coordination sphere. These studies suggested that the product was bound end-on to Mo(IV) in an Mo-O-R fashion [98][78].

Subsequently, Kirk and coworkers used a combination of electronic absorption and resonance Raman spectroscopies to spectroscopically interrogate the nature of the Mo(IV)-product species in XO/XDH through the use of two different heavy atom congeners of the lumazine substrate [89,90,97][71][72][77]. The two-electron oxidized 4-thioviolapterin (4-TV) and 2,4-thioviolapterin (2,4-TV) bind tightly to the Mo(IV) centers of wt-XDH and the Q102G and Q197A variants. These important studies provided deep insight into specific Moco-protein interactions. The electronic absorption and rR spectroscopies were evaluated in the context of vibrational and spectroscopic computations, and this enabled an unambiguous assignment of the intense Mo → violapterin charge transfer transition as being a Mo(xy) → violapterin (π*) metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) excitation [97][77]. The intensity of this low-energy MLCT band derives from the Mo(xy) redox orbital being oriented orthogonal to the product ring plane, since this allows for strong overlap between the Mo(xy) orbital and the π* orbitals of the thioviolapterin product molecules [89,90,97][71][72][77]. Thus, this MLCT transition can be described as a one-electron promotion from the doubly occupied Mo(xy) orbital to the LUMO of the product, and this effectively produces a hole on the Mo center (e.g., a formal Mo(V) center with the transfer of a full electron).

2.3. What Is Known about Pterin Oxidation State and Pterin Redox Reactivity in Moco

2.3.1. Earliest Redox Studies on PDT in Molybdenum Enzymes

Rajagopalan was the first to probe the redox state of Moco in several studies initiated shortly after his proposal of its tetrahydropterin structure using detailed absorption spectral analyses [106,107][83][84]. The absorption spectrum of XO includes a 300 nm absorption consistent with either a tetrahydropterin or an unstable quinonoid dihydropterin, but it eliminated the possibility of a 7,8-dihydropterin structure. Oxidation of sulfite oxidase and xanthine oxidase by the redox dye dichlorophenylindophenol (DCIP) showed a 2e−/2H+ reaction occurred at the PDT to produce a fully oxidized pterin that was identified by electronic absorption spectroscopy, and this result indicated that Moco in both XO and SO possesses a pterin at the dihydro-level of reduction [106,107][83][84]. On the basis of extensive reactivity studies in the Rajagopalan labs [106[83][84],107], the native state of the pterin of Moco in XO was proposed to be a quinonoid dihydropterin, whereas SO was argued to have a different tautomeric dihydropterin structur.2.3.2. Redox Studies on Pyranopterin

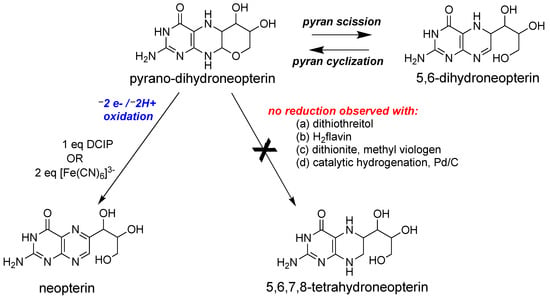

Following the discovery of the pyranopterin structure of PDT [76,77][63][64], Burgmayer et al. investigated the redox behavior of a synthetic reduced pyranopterin in reactions with either DCIP or ferricyanide to corroborate the Rajagopalan studies [92,111,112,113][85][86][87][88]. The work demonstrated that a reduced tetrahydropyranopterin (i.e., the pyrano-dihydroneopterin in Figure 74) reacted as a dihydropterin; that is, it required 1 eq DCIP or 2 eq ferricyanide to generate the oxidized pterin product neopterin (Figure 74).

Figure 74. Redox reactivity of a model pyranopterin.

2.3.3. Role of PDT Oxidation State in Reductive Activation of DMSO Family Enzymes

It is well known that enzymes within the DMSOR family are isolated as heterogeneous samples that can be activated by a prereduction step that reduces unknown species. A recent investigation of such a reductive activation in nitrate reductase concludes with the proposal that it is the pterin of PDT that requires reduction [115,116,117]. Dissimilatory

Nitrate reductase NarGHI from E. coli was the first enzyme identified by protein crystallography to possess a Moco structure with one pyranopterin (proximal) and one bicyclic, pyran-opened pterin (distal) (Figure 21d) [81][68]. Variants were made at amino acid residues having H-bonding interactions at the O atom of the open, distal PDT pterin (Figure 21d) to assess the effect on the Mo redox potential Em [118][92]. It was found that when Ser719 was replaced by alanine, there was very little effect on Mo Em, whereas the H1163A and H1184A variants caused large effects (ΔEm values of −88 and −36 mV, respectively). On this basis, it was proposed that a charge transfer relay involving both His residues and three water molecules regulates the protonation state of the pyran-OH and thereby the Mo reduction potential. This charge relay was also proposed as initiating the pyranopterin ring opening reaction of the distal PDT via proton abstraction. A second mutation investigated the amino acid bridging the proximal and distal pterins at their N5 atom positions within each pterin. For NarGHI nitrate reductase and most members of the DMSOR family, this bridging residue is a histidine (His1092 in Figure 43d), whose H-bonding to the proximal PDT at pterin N5 is believed to maintain the reduced pyranopterin structure. Alanine variants of His1092 and His1098 also caused large ΔEm values of −143 and −101 mV, respectively. The results of the work support the hypothesis that changes in the pterin component of the PDT, both in terms of its oxidation state and its structure (or tautomeric form), can affect the Mo reduction potential. This modulation of the reduction potential may be used to tune an enzyme to function with a variety of substrates, th

Redox reactivity of a model pyranopterin.

E. coli nitrate reductase (Ec Nar) was studied using protein film voltammetry to obtain kinetic parameters for the reductive activation [115]. Based on the kinetic analysis, there are two inactive species in equilibrium in the Nar enzyme, and only one of these is reductively activated by sodium dithionite. Furthermore, it is proposed that the equilibrium involves the cyclization of an open pterin form of PDT to a cyclized pyranopterin form of PDT prior to the reduction step that produces the active Nar enzyme.

2.3.3. Role of PDT Oxidation State in Reductive Activation of DMSO Family Enzymes

It is well known that enzymes within the DMSOR family are isolated as heterogeneous samples that can be activated by a prereduction step that reduces unknown species. A recent investigation of such a reductive activation in nitrate reductase concludes with the proposal that it is the pterin of PDT that requires reduction [89][90][91]. Dissimilatory

nitrate reductase (Ec Nar) was studied using protein film voltammetry to obtain kinetic parameters for the reductive activation [89]. Based on the kinetic analysis, there are two inactive species in equilibrium in the Nar enzyme, and only one of these is reductively activated by sodium dithionite. Furthermore, it is proposed that the equilibrium involves the cyclization of an open pterin form of PDT to a cyclized pyranopterin form of PDT prior to the reduction step that produces the active Nar enzyme.

2.3.4. Pterin Protein Environment in DMSOR Family Enzymes Correlates with Mo Reduction Potential

3. What Has Been Learned about Moco from Model Studies Directly Probing PDT-Mo Interactions?

3.1. Studies That Define “Simple” Mo-Ditholene Interactions

3.1.1. Tp*MoO(bdt)

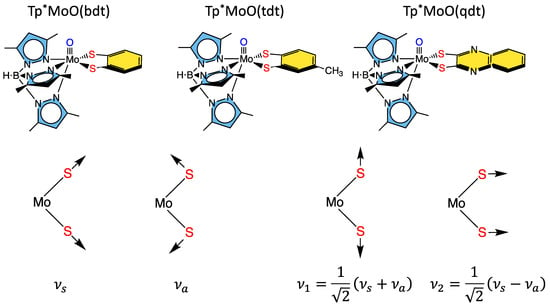

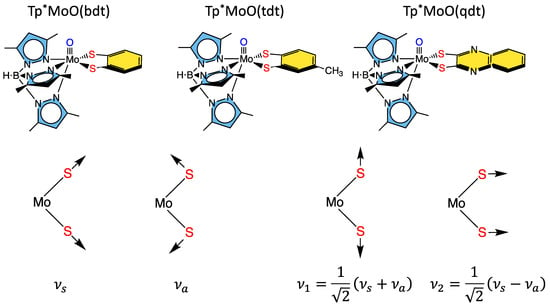

Some of the first comprehensive spectroscopic studies on oxo-molybdenum dithiolene model complexes were performed by Kirk and Enemark on Tp*MoO(dithiolene) complexes (Tp* = tris-(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)hydroborate; dithiolene = bdt, tdt, qdt) (Figure 85) [2,84,91,122][2][93][94][95]. The work showed evidence for low-energy dithiolene → Mo LMCT transitions that indicated a three-center, pseudo-σ, Mo(xy)—S(dithiolene) bonding interaction is present in this system. From an electron transfer viewpoint, these results supported the hypothesis that in-plane Mo-S covalency could be important in modulating active site reduction potentials by destabilizing the Mo(xy) redox orbital in mono-oxo sites. For mono-oxo enzyme active sites [84[93][96][97],123,124], the strong ligand field produced by the Mo≡O bond orients the Mo(xy) orbital to be orthogonal to this bond, with implications for both atom and electron transfer reactivity [123][96]. Thus, if the pyranopterin component of the PDT is involved in electron transfer regeneration of catalytically competent active sites, there must be a long-range superexchange pathway that couples the Mo(xy) redox orbital into the PDT [84,110,125][93][98][99]. The low-frequency rR spectra of these key molecules show two important totally symmetric vibrational modes that can be described: S-Mo-S stretching and bending (Figure 85, bottom left) [2,84,91,122][2][93][94][95]. Since these vibrations have the same symmetry, they can mix to yield the vibrational modes given at the bottom right of Figure 85.

Figure 85. Top: Tp*MoO(dithiolene) first-generation model complexes that have been extensively probed spectroscopically using a combination of MCD, electronic absorption, photoelectron, electron paramagnetic resonance, and resonance Raman spectroscopies. Bottom: Symmetry coordinates for two totally symmetric low-frequency normal modes and their respective linear combinations.

3.1.2. Remote Charge Effects on Oxygen Atom Transfer Reactivity

Differences in the electron-donating ability of the PDT, which could result from S-fold distortions, contributing thiol-thione resonance forms, PDT protonation, etc., possess the potential to affect the rates of oxygen atom transfer reactivity in pyranopterin Mo enzymes. Recent model compound studies have shown that changing the molecular charge by a single unit at a position remote from the Mo ion can have dramatic effects on thermodynamic parameters and reaction kinetics related to oxygen atom transfer reactivity [126][100]. In comparing Tp*MoVIO2Cl with [Tpm*MoVIO2Cl]1+, differences in their respective molecular charges arise from a single atom substitution (N → C). The change in charge at the virtual parity of their geometric structures leads to a dramatic +350 mV change in the MoVI/MoV reduction potential. A comparative analysis of the frontier molecular orbitals and electrostatic potential energy surfaces between Tp*MoIVO2Cl and [Tpm*MoIVO2Cl]1+ showed that the remarkable shift in the reduction potential can be explained by a stabilization of the [Tpm*MoIVO2Cl]1+ LUMO. This LUMO stabilization results in an increase in the oxygen atom transfer reaction rate by several orders of magnitude, and the observed rate acceleration was accompanied by a larger thermodynamic driving force in accordance with the Bell-Evans-Polanyi principle. Thus, the Mo reduction potential in the enzymes can be modified by a few hundred mVs with changes in charge that are remote from the Mo center. This charge effect study conclusively showed that the structural changes that accompany charge changes are likely to be difficult or even impossible to observe in the enzymes using protein X-ray crystallography.

3.1.3. Mo-Dithione Interactions Relevant to Molybdoenzymes

Although the Mo ion redox cycles between the Mo(IV) and Mo(VI) states in most molybdoenzymes, with one-electron nitrite to NO• and the tungstoenzyme-catalyzed non-redox hydration of acetylene being notable examples [28[28][29][30][31][32][101][102][103][104],29,30,31,32,127,128,129,130], the PDT has not been shown to be redox active in catalysis [48], although it is capable of storing up to six redox equivalents. Two of these equivalents are localized on the dithiolene, and four are localized on the pterin. Spectroscopic and electronic structure studies on [Mo4+O(iPr2Pipdt)2Cl][PF6] (Pipdt = N,N-piperazine-2,3-dithione) have been used to explore the potential non-innocence of the dithiolene in PDT [131][105]. The electronic absorption spectrum of this complex is unusual for a Mo(IV) complex in that it possesses a relatively intense (ε ~ 1400 M−1cm−1) low-energy (E ~ 13,500 cm−1) metal-to-ligand charge-transfer (LMCT) band. Typically, low-energy LMCT transitions in mono-oxo Mo sites are not observed due to the large terminal oxo-derived ligand field splitting of the t2g orbitals and the double occupancy of the lowest energy Mo(xy) orbital. However, if the dithiolene is oxidized to a dithione and ligand acceptor orbitals are available, low-energy MLCT may be observed. This is the case for [Mo4+O(iPr2Pipdt)2Cl]1+, where the MLCT has been assigned as Mo(xy) → dithione(π*) HOMO → LUMO transition based on spectral computations and resonance Raman enhancement of bands with C–C and C–S stretching characters. The iPr2Pipdt ligand was described in valence bond terms using a natural bond orbital approach to be comprised of a hybrid of contributing dithione (63%) and di-zwitterionic dithiolene (37%) resonance structures. The π-acceptor character of this type of dithione was also shown in studies on MoO(SPh)2(iPr2Dt0) (iPr2Dt0 = N,N′-isopropyl-piperazine-2,3-dithione), where an intense thiolate → dithione ligand-to-ligand CT band was assigned at ~18,000 cm−1. This assignment was based on spectroscopic computations and resonance Raman enhancement of a 378 cm−1 vibration that was shown to possess dithione ligand S−Mo−S + C−N stretch character. The π-acceptor character of the ligand is also exemplified in a dramatic dithione ligand fold angle distortion of 70°, which derives from the pseudo-Jahn–Teller effect [91][94].

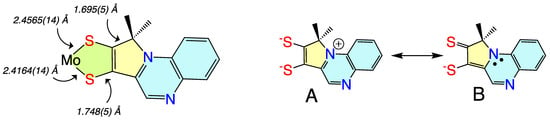

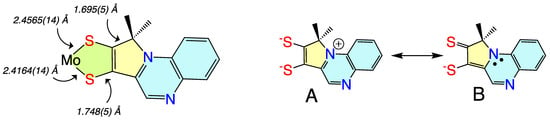

3.1.4. Donor-Acceptor Quinoxaline Dithiolene Ligands

Non-innocent metal-ligand redox behavior in molybdenum dithiolene complexes that possess ligands comprised of nitrogen heterocycles was initially reported by Pilato in a series of pyridinyl- and quinoxalinyl- dithiolene complexes of molybdenum of the type Cp2Mo(S2C2(heterocycle)H) [132][106], foreshadowing the results scholars would obtain using pyranopterin dithiolene ligands. The potential for such non-innocent behavior in the molybdenum cofactor was originally demonstrated using a ligand (pyrrolo-S2BMOQO) comprised of an N-heterocycle (quinoxaline) that is appended to a dithiolene fragment that was covalently bound to a Mo(IV) ion [133][107]. These quinoxalyldithiolene ligands effectively served as first-generation models for how the PDT may function in Moco. Tp*MoO(pyrrolo-S2BMOQO) is formed from the dehydration of TEA[Tp*MoO(S2BMOQO)] (TEA = tetraethylammonium; Tp* = hydrotris(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)-borate), where an intramolecular cyclization within the S2BMOQO ligand occurs. A combination of DFT computations, which were interpreted in the context of resonance Raman and electronic absorption spectroscopies and complemented by X-ray crystallographic studies, revealed that an asymmetric dithiolene chelate was present in Tp*MoO(pyrrolo-S2BMOQO). Additionally, it was shown that this five-membered MoS2C2 chelate ring possessed considerable thione-thiolate character. A valence bond description was used to describe the observed Mo-ligand chelate ring thione-thiolate bonding character, and this analysis showed that there were two dominant resonance structures that contribute to the electronic structure description (Figure9 6).

Figure 96. (left) Bond lengths determined from X-ray crystallography for Tp*MoO(pyrrolo-S2BMOQO). (right) Contributing resonance structures for the ligand showing dominant dithiolene (A) and thione-thiolate (B) structures.

3.2. Model Systems That Incorporate Both Dithiolene and Pyranopterin Structures on Molybdenum

The first Moco model compound to successfully incorporate a pterin dithiolene ligand on a Mo(4+) ion was reported from Pilato’s labs in 1991 [134,135][108][109]. These Cp2Mo(IV)(S2C2(pterin)(COMe)) systems were constructed on a bis-cyclopentadienyl-Mo(IV) structure that lacked a terminal oxo ligand. Limited studies of this molecule demonstrated one electron oxidation to Mo(V) and reactivity towards acids. Subsequently, Garner and coworkers [136][110] reported a pterin dithiolene ligand in a related complex, CpCo(S2C2(pterin)(H)).

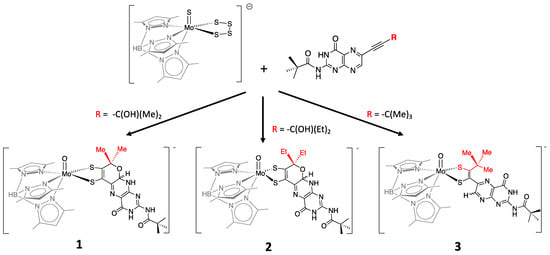

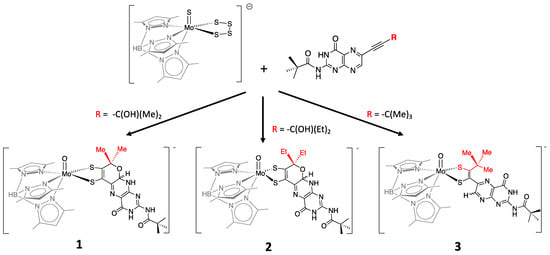

More recently, a number of pterin- and quinoxaline-dithiolene Mo compounds have been designed in the Burgmayer labs. Each is synthesized from the reaction of a molybdenum tetrasulfide precursor [Tp*MoS(S4)]− with a suitably substituted pterinyl- or quinoxalyl-alkyne, as depicted in Figure 107. The pivaloyl group added to the exocyclic amine group of the pterin overcomes the notorious insolubility of pterins. Those complexes shown in Figure 107 have been studied in detail to provide considerable insight about the (pterin-dithiolene)-Mo system.

Figure 107.

Pterin-dithiolene model compounds for Moco.

4. What We Have Learned from Model Systems That Pertain to Moco in Enzymes? An Update

4.1. Previous Roles of the Pterin Defined

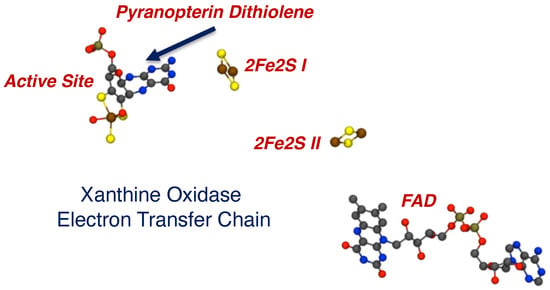

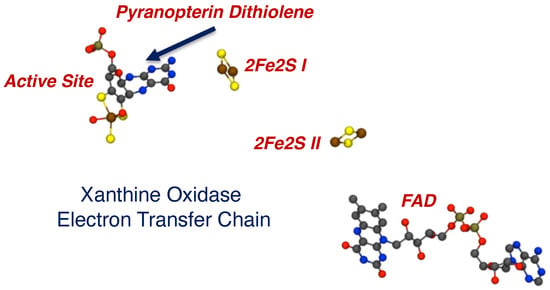

The PDT is the least understood critical component of Moco in all pyranopterin Mo and W enzymes. This is remarkable, given the complex biosynthetic pathway and the ubiquitous nature of PDT in all the enzymes. At present, there is good evidence for three key roles of the PDT in catalysis, and these include functioning as an anchor for the Mo/W ion, serving as a through-bond electron transfer conduit for obligatory one-electron transfers in the electron transfer half reaction of the enzymes, and, with respect to the dithiolene component of the PDT, enabling redox potential modulation of the active site. Early protein crystallography studies indicated that the dithiolene component of the PDT could be either completely or partially dissociated from the metal ion, suggesting a role for this behavior in the catalytic cycles of some pyranopterin-containing enzymes. However, it is now understood that these structures represent active sites that have been damaged by the high flux of the X-ray beam during data collection. Thus, bidentate coordination of the dithiolene moiety is necessary for catalysis. Studies by Hille and coworkers were among the first to suggest a role of the PDT in electron transfer regeneration of the active site in xanthine oxidase (

Figure 23) [148,149,150]. An extensive amount of model compound studies, including those detailed here, strongly suggest that the nature of the dithiolene ligand, remote charge effects, and the degree of the sulfur-fold angle can all affect the effective nuclear charge of the metal ion to drive large changes in the Mo redox potential. However, new roles for the PDT have been suggested that involve different oxidation states of the pterin component of the PDT, hydrogen bonding and proton transfer involving the pterin, and the role of thione-thiol resonance structure contributions to the electronic structure of the dithiolene chelate.8) [111][112][113]. An extensive amount of model compound studies, including those detailed here, strongly suggest that the nature of the dithiolene ligand, remote charge effects, and the degree of the sulfur-fold angle can all affect the effective nuclear charge of the metal ion to drive large changes in the Mo redox potential. However, new roles for the PDT have been suggested that involve different oxidation states of the pterin component of the PDT, hydrogen bonding and proton transfer involving the pterin, and the role of thione-thiol resonance structure contributions to the electronic structure of the dithiolene chelate.

Figure 238.

The electron transfer chain in XO, indicating a vectorial pathway for electron egress involving the Mo ion, the PDT, two spinach ferredoxin type 2Fe2S clusters, and a flavin. Electrons exit the enzyme at FAD.

4.2. Recent Results Define New Roles for the PDT in Catalysis

An early hypothesis that the PDT might serve to modulate the Mo redox potential has now been demonstrated and quantified for pterin-dithiolene model complexes. The partially reduced pyranopterin structure is electron withdrawing with respect to the Mo-dithiolene unit, and this results in the Mo(V) ion being a stronger oxidant in these systems. The redox-flexible dithiolene responds by accessing a partially oxidized thione/thiolate resonance structure. Pyran ring cleavage severs the PDT electron conduit, as the dithiolene is now electronically isolated from the pterin, which can now rotate out of the Mo-dithiolene plane. Reduction of pyranopterin is expected to also decrease this electronic relay from Mo-dithiolene to pterin as the sp3-hybridized bridgehead carbon between pterin and dithiolene interrupts extended π-conjugation in the PDT.

It is worth emphasizing that the degree of thione-thiolate character in the chelate ring is Mo oxidation state-specific, with thione-thiolate character being observed only for Mo(IV) [86,92,139][85][114][115]. Higher oxidation states of Mo typically result in the dithiol resonance form of the ligand dominating and an increase in the chelate ring S-S fold angle to reduce the effective nuclear charge on the Mo ion [79,88,91,122][66][94][95][116].

References

- Ingersol, L.J.; Kirk, M.L. Structure, Function, and Mechanism of Pyranopterin Molybdenum and Tungsten Enzymes. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry III; Constable, E.C., Parkin, G., Que, L., Jr., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 790–811.

- Yang, J.; Enemark, J.H.; Kirk, M.L. Metal-Dithiolene Bonding Contributions to Pyranopterin Molybdenum Enzyme Reactivity. Inorganics 2020, 8, 19.

- Kirk, M.L.; Kc, K. Molybdenum and Tungsten Cofactors and the Reactions They Catalyze. Transition Metals and Sulfur—A Strong Relationship for Life. In Metal Ions in Life Sciences; Sosa Torres, M., Kroneck, P., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Volume 20, pp. 313–342.

- Hille, R.; Schulzke, C.; Kirk, M.L. Molybdenum and Tungsten Enzymes; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2017.

- Kirk, M.L.; Hille, R. Spectroscopic Studies of Mononuclear Molybdenum Enzyme Centers. Molecules 2022, 27, 4802.

- Hille, R.; Hall, J.; Basu, P. The Mononuclear Molybdenum Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3963–4038.

- Hille, R.; Nishino, T.; Bittner, F. Molybdenum enzymes in higher organisms. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 1179–1205.

- Peglow, S.; Toledo, A.H.; Anaya-Prado, R.; Lopez-Neblina, F.; Toledo-Pereyra, L.H. Allopurinol and xanthine oxidase inhibition in liver ischemia reperfusion. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2011, 18, 137–146.

- Nishino, T. The Conversion of Xanthine Dehydrogenase to Xanthine Oxidase and the Role of the Enzyme in Reperfusion Injury. J. Biochem. 1994, 116, 1–6.

- Kumar, R.; Joshi, G.; Kler, H.; Kalra, S.; Kaur, M.; Arya, R. Toward an Understanding of Structural Insights of Xanthine and Aldehyde Oxidases: An Overview of their Inhibitors and Role in Various Diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2018, 38, 1073–1125.

- Ahire, D.; Basit, A.; Christopher, L.J.; Iyer, R.; Leeder, J.S.; Prasad, B. Interindividual Variability and Differential Tissue Abundance of Mitochondrial Amidoxime Reducing Component Enzymes in Humans. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 191.

- Mota, C.; Esmaeeli, M.; Coelho, C.; Santos-Silva, T.; Wolff, M.; Foti, A.; Leimkuhler, S.; Romao, M.J. Human aldehyde oxidase (hAOX1): Structure determination of the Moco-free form of the natural variant G1269R and biophysical studies of single nucleotide polymorphisms. FEBS Open Bio 2019, 9, 925–934.

- Mota, C.; Coelho, C.; Leimkuhler, S.; Garattini, E.; Terao, M.; Santos-Silva, T.; Romao, M.J. Critical overview on the structure and metabolism of human aldehyde oxidase and its role in pharmacokinetics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 368, 35–59.

- Beedham, C.; Miceli, J.J.; Obach, R.S. Ziprasidone metabolism, aldehyde oxidase, and clinical implications. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003, 23, 229–232.

- Vickers, S.; Polsky, S.L. The biotransformation of nitrogen containing xenobiotics to lactams. Curr. Drug Metab. 2000, 1, 357–389.

- Pritsos, C.A. Cellular distribution, metabolism and regulation of the xanthine oxidoreductase enzyme system. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2000, 129, 195.

- Maini Rekdal, V.; Bess, E.N.; Bisanz, J.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Balskus, E.P. Discovery and inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Science 2019, 364, eaau6323.

- Kubitza, C.; Bittner, F.; Ginsel, C.; Havemeyer, A.; Clement, B.; Scheidig, A.J. Crystal structure of human mARC1 reveals its exceptional position among eukaryotic molybdenum enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11958–11963.

- Ott, G.; Havemeyer, A.; Clement, B. The mammalian molybdenum enzymes of mARC. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 20, 265–275.

- Havemeyer, A.; Lang, J.A.; Clement, B. The fourth mammalian molybdenum enzyme mARC: Current state of research. Drug Metab. Rev. 2011, 43, 524–539.

- Havemeyer, A.; Grünewald, S.; Wahl, B.; Bittner, F.; Mende, R.; Erdélyi, P.; Fischer, J.; Clement, B. Reduction of N-Hydroxy-sulfonamides, Including N-Hydroxy- valdecoxib, by the Molybdenum-Containing Enzyme mARC. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 1917–1921.

- Yang, J.; Struwe, M.; Scheidig, A.; Mengell, J.; Clement, B.; Kirk, M.L. Active Site Structures of the Escherichia coli N-Hydroxylaminopurine Resistance Molybdoenzyme YcbX. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 5315–5319.

- Clement, B.; Struwe, M.A. The History of mARC. Molecules 2023, 28, 4713.

- Schwarz, G. Molybdenum cofactor and human disease. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 31, 179–187.

- Gruenewald, S.; Wahl, B.; Bittner, F.; Hungeling, H.; Kanzow, S.; Kotthaus, J.; Schwering, U.; Mendel, R.R.; Clement, B. The Fourth Molybdenum Containing Enzyme mARC: Cloning and Involvement in the Activation of N-Hydroxylated Prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 8173–8177.

- Tejada-Jimenez, M.; Chamizo-Ampudia, A.; Calatrava, V.; Galvan, A.; Fernandez, E.; Llamas, A. From the Eukaryotic Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis to the Moonlighting Enzyme mARC. Molecules 2018, 23, 3287.

- Llamas, A.; Chamizo-Ampudia, A.; Tejada-Jimenez, M.; Galvan, A.; Fernandez, E. The molybdenum cofactor enzyme mARC: Moonlighting or promiscuous enzyme? BioFactors 2017, 43, 486–494.

- Maia, L.; Moura, J.G. Nitrite reduction by molybdoenzymes: A new class of nitric oxide-forming nitrite reductases. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 20, 403–433.

- Wang, J.; Krizowski, S.; Fischer-Schrader, K.; Niks, D.; Tejero, J.; Sparacino-Watkins, C.; Wang, L.; Ragireddy, V.; Frizzell, S.; Kelley, E.E.; et al. Sulfite Oxidase Catalyzes Single-Electron Transfer at Molybdenum Domain to Reduce Nitrite to Nitric Oxide. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 23, 283–294.

- Sparacino-Watkins, C.E.; Tejero, J.S.; Sun, B.; Gauthier, M.C.; Thomas, J.; Ragireddy, V.; Merchant, B.A.; Wang, J.; Azarov, I.; Basu, P.; et al. Nitrite Reductase and Nitric-oxide Synthase Activity of the Mitochondrial Molybdopterin Enzymes mARC1 and mARC2. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 10345–10358.

- Maia, L.B.; Moura, J.J.G. Nitrite reduction by xanthine oxidase family enzymes: A new class of nitrite reductases. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 16, 443–460.

- Yang, J.; Giles, L.J.; Ruppelt, C.; Mendel, R.R.; Bittner, F.; Kirk, M.L. Oxyl and Hydroxyl Radical Transfer in Mitochondrial Amidoxime Reducing Component-Catalyzed Nitrite Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5276–5279.

- Giles, L.J.; Ruppelt, C.; Yang, J.; Mendel, R.R.; Bittner, F.; Kirk, M.L. Molybdenum Site Structure of MOSC Family Proteins. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 9460–9462.

- Kirk, M.L.; Stein, B. The Molybdenum Enzymes. In Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II, 2nd ed.; Jan, R., Kenneth, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 263–293.

- Hemann, C.; Hood, B.L.; Fulton, M.; Hansch, R.; Schwarz, G.; Mendel, R.R.; Kirk, M.L.; Hille, R. Spectroscopic and kinetic studies of Arabidopsis thaliana sulfite oxidase: Nature of the redox-active orbital and electronic structure contributions to catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 16567.

- Enemark, J.H. Consensus structures of the Mo(v) sites of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes derived from variable frequency pulsed EPR spectroscopy, isotopic labelling and DFT calculations. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 13202–13210.

- Mendel, R.R.; Leimkuhler, S. The biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactors. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 20, 337–347.

- Wollers, S.; Heidenreich, T.; Zarepour, M.; Zachmann, D.; Kraft, C.; Zhao, Y.D.; Mendel, R.R.; Bittner, F. Binding of sulfurated molybdenum cofactor to the C-terminal domain of ABA3 from Arabidopsis thaliana provides insight into the mechanism of molybdenum cofactor sulfuration. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 9642–9650.

- Schwarz, G.; Mendel, R.R. Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis and Molybdoenzymes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 623–647.

- Heidenreich, T.; Wollers, S.; Mendel, R.R.; Bittner, F. Characterization of the NifS-like domain of ABA3 from Arabidopsis thaliana provides insight into the mechanism of molybdenum cofactor sulfuration. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 4213–4218.

- Wahl, B.; Reichmann, D.; Niks, D.; Krompholz, N.; Havemeyer, A.; Clement, B.; Messerschmidt, T.; Rothkegel, M.; Biester, H.; Hille, R.; et al. Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of the human mitochondrial amidoxime reducing components hmARC-1 and hmARC-2 suggests the existence of a new molybdenum-enzyme family in eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 37847–37859.

- Anantharaman, V.; Aravind, L. MOSC domains: Ancient, predicted sulfur-carrier domains, present in diverse metal-sulfur cluster biosynthesis proteins including Molybdenum cofactor sulfurases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002, 207, 55–61.

- Heider, J.; Ma, K.; Adams, M.W.W. Purification, Characterization, and Metabolic Function of Tungsten-Containing Aldehyde Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase from the Hyperthermophilic and Proteolytic Archaeon Thermococcus Strain ES-1. J. Bacter. 1995, 177, 4757–4764.

- Schut, G.J.; Thorgersen, M.P.; Poole, F.L.; Haja, D.K.; Putumbaka, S.; Adams, M.W.W. Tungsten enzymes play a role in detoxifying food and antimicrobial aldehydes in the human gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2109008118.

- Rekdal, V.M.; Bernadino, P.N.; Luescher, M.U.; Kiamehr, S.; Le, C.; Bisanz, J.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Bess, E.N.; Balskus, E.P. A widely distributed metalloenzyme class enables gut microbial metabolism of host- and diet-derived catechols. elife 2020, 9, e50845.

- Rekdal, V.M.; Balskus, E.P. Gut Microbiota: Rational Manipulation of Gut Bacterial Metalloenzymes Provides Insights into Dysbiosis and Inflammation. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 2291–2293.

- Struwe, M.A.; Kalimuthu, P.; Luo, Z.Y.; Zhong, Q.F.; Ellis, D.; Yang, J.; Khadanand, K.C.; Harmer, J.R.; Kirk, M.L.; McEwan, A.G.; et al. Active site architecture reveals coordination sphere flexibility and specificity determinants in a group of closely related molybdoenzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100672.

- Ingersol, L.J.; Yang, J.; Khadanand, K.C.; Pokhrel, A.; Astashkin, A.V.; Weiner, J.H.; Johnston, C.A.; Kirk, M.L. Addressing Ligand-Based Redox in Molybdenum-Dependent Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 142, 2721–2725.

- Dhouib, R.; Othman, D.; Lin, V.; Lai, X.J.; Wijesinghe, H.G.S.; Essilfie, A.T.; Davis, A.; Nasreen, M.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Hansbro, P.M.; et al. A Novel, Molybdenum-Containing Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase Supports Survival of Haemophilus influenzae in an In vivo Model of Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1743.

- Lansbury, L.; Lim, B.; Baskaran, V.; Lim, W.S. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 266–275.

- Burgmayer, S.J.N.; Kirk, M.L. The Role of the Pyranopterin Dithiolene Component of Moco in Molybdoenzyme Catalysis. In Metallocofactors That Activate Small Molecules: With Focus on Bioinorganic Chemistry; Ribbe, M.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 179, pp. 101–151.

- Mendel, R.R. The History of the Molybdenum Cofactor-A Personal View. Molecules 2022, 27, 4934.

- Chrysochos, N.; Ahmadi, M.; Trentin, I.; Lokov, M.; Tshepelevitsh, S.; Ullmann, G.M.; Leito, I.; Schulzke, C. Aiding a Better Understanding of Molybdopterin: Syntheses, Structures, and pK(a) Value Determinations of Varied Pterin-Derived Organic Scaffolds Including Oxygen, Sulfur and Phosphorus Bearing Substituents. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1230, 129867.

- Leimkühler, S. The biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactors in Escherichia coli. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 2007–2026.

- Krausze, J.; Hercher, T.W.; Zwerschke, D.; Kirk, M.L.; Blankenfeldt, W.; Mendel, R.R.; Kruse, T. The functional principle of eukaryotic molybdenum insertases. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 1739–1753.

- Iobbi-Nivol, C.; Leimkühler, S. Molybdenum enzymes, their maturation and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2013, 1827, 1086–1101.

- Kruse, T. Eukaryotic Molybdenum Insertases. Encycl. Inorg. Bioinorg. Chem. 2020, 1–6.

- Hercher, T.W.; Krausze, J.; Hoffmeister, S.; Zwerschke, D.; Lindel, T.; Blankenfeldt, W.; Mendel, R.R.; Kruse, T. Insights into the Cnx1E catalyzed MPT-AMP hydrolysis. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20191806.

- Mendel, R.R. The Molybdenum Cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 13165–13172.

- Probst, C.; Yang, J.; Krausze, J.; Hercher, T.W.; Richers, C.P.; Spatzal, T.; Khadanand, K.C.; Giles, L.J.; Rees, D.C.; Mendel, R.R.; et al. Mechanism of molybdate insertion into pterin-based molybdenum cofactors. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 758–765.

- Dobbek, H.; Huber, R. The Molybdenum and Tungsten Cofactors: A Crystallographic View. In Metal Ions in Biological Systems; Sigel, A., Sigel, H., Eds.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 39, pp. 227–263.

- Johnson, J.L.; Rajagopalan, K.V.; Mukund, S.; Adams, M.W.W. Identification of Molybdopterin As the Organic-Component of the Tungsten Cofactor in 4 Enzymes From Hyperthermophilic Archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 4848–4852.

- Chan, M.K.; Mukund, S.; Kletzin, A.; Adams, M.W.W.; Rees, D.C. Structure of a Hyperthermophilic Tungstopterin Enzyme, Aldehyde Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase. Science 1995, 267, 1463–1469.

- Schindelin, H.; Kisker, C.; Hilton, J.; Rajagopalan, K.V.; Rees, D.C. Crystal structure of DMSO reductase: Redox-linked changes in molybdopterin coordination. Science 1996, 272, 1615–1621.

- Schindelin, H.; Kisker, C.; Rees, D.C. The molybdenum-cofactor: A crystallographic perspective. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 2, 773–781.

- Rothery, R.A.; Stein, B.; Solomonson, M.; Kirk, M.L.; Weiner, J.H. Pyranopterin conformation defines the function of molybdenum and tungsten enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14773–14778.

- Rothery, R.A.; Weiner, J.H. Shifting the metallocentric molybdoenzyme paradigm: The importance of pyranopterin coordination. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 20, 349–372.

- Bertero, M.G.; Rothery, R.A.; Palak, M.; Hou, C.; Lim, D.; Blasco, F.; Weiner, J.H.; Strynadka, N.C.J. Insights into the respiratory electron transfer pathway from the structure of nitrate reductase A. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003, 10, 681–687.

- Kloer, D.P.; Hagel, C.; Heider, J.; Schulz, G.E. Crystal structure of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase from Aromatoleum aromaticum. Structure 2006, 14, 1377–1388.

- Youngblut, M.D.; Tsai, C.L.; Clark, I.C.; Carlson, H.K.; Maglaqui, A.P.; Gau-Pan, P.S.; Redford, S.A.; Wong, A.; Tainer, J.A.; Coates, J.D. Perchlorate Reductase Is Distinguished by Active Site Aromatic Gate Residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 9190–9202.

- Dong, C.; Yang, J.; Leimkühler, S.; Kirk, M.L. Pyranopterin Dithiolene Distortions Relevant to Electron Transfer in Xanthine Oxidase/Dehydrogenase. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 7077–7079.

- Dong, C.; Yang, J.; Reschke, S.; Leimkühler, S.; Kirk, M.L. Vibrational Probes of Molybdenum Cofactor–Protein Interactions in Xanthine Dehydrogenase. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 6830–6837.

- Garton, S.D.; Hilton, J.; Oku, H.; Crouse, B.R.; Rajagopalan, K.V.; Johnson, M.K. Active Site Structures and Catalytic Mechanism of Rhodobacter sphaeroides Dimethyl Sulfoxide Reductase as Revealed by Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 12906–12916.

- Johnson, M.K.; Garton, S.D.; Oku, H. Resonance Raman as a Direct Probe for the Catalytic Mechanism of Molybdenum Oxotransferases. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 2, 797–803.

- Bell, A.F.; He, X.; Ridge, J.P.; Hanson, G.R.; McEwan, A.G.; Tonge, P.J. Active site heterogeneity in dimethyl sulfoxide reductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus revealed by Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 440–448.

- Garton, S.D.; Temple, C.A.; Dhawan, I.K.; Barber, M.J.; Rajagopalan, K.V.; Johnson, M.K. Resonance Raman Characterization of Biotin Sulfoxide Reductase: Comparing Oxomolybdenum Enzymes in the Me2SO Reductase Family. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 6798–6805.

- Yang, J.; Dong, C.; Kirk, M.L. Xanthine oxidase-product complexes probe the importance of substrate/product orientation along the reaction coordinate. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 13242–13250.

- Hemann, C.; Ilich, P.; Stockert, A.L.; Choi, E.Y.; Hille, R. Resonance Raman studies of xanthine oxidase: The reduced enzyme—Product complex with violapterin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 3023–3031.

- Davis, M.; Olson, J.; Palmer, G. The Reaction of Xanthine Oxidase with Lumazine: Characterization of the Reductive Half-reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 3526–3533.

- Kim, J.H.; Ryan, M.G.; Knaut, H.; Hille, R. The reductive half-reaction of xanthine oxidase: The involvement of prototropic equilibria in the course of the catalytic sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 6771–6780.

- Hemann, C.; Ilich, P.; Hille, R. Vibrational spectra of lumazine in water at pH 2–13: Ab initio calculation and FTIR/Raman spectra. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 2139–2155.

- Pauff, J.M.; Cao, H.; Hille, R. Substrate Orientation and Catalysis at the Molybdenum Site in Xanthine Oxidase Crystal Structures in Complex with Xanthine and Lumazine. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 8751–8758.

- Gardlik, S.; Rajagopalan, K. Oxidation of Molybdopterin in Sulfite Oxidase by Ferricyanide- Effect on Electron Transfer Activities. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 4889–4895.

- Gardlik, S.; Rajagopalan, K.V. The State of Reduction of Molybdopterin in Xanthine-Oxidase and Sulfite Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 13047–13054.

- Gates, C.; Varnum, H.; Getty, C.; Loui, N.; Chen, J.; Kirk, M.L.; Yang, J.; Nieter Burgmayer, S.J. Protonation and Non-Innocent Ligand Behavior in Pyranopterin Dithiolene Molybdenum Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 13728–13742.

- Gisewhite, D.R.; Yang, J.; Williams, B.R.; Esmail, A.; Stein, B.; Kirk, M.L.; Burgmayer, S.J.N. Implications of Pyran Cyclization and Pterin Conformation on Oxidized Forms of the Molybdenum Cofactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12808–12818.

- Williams, B.R.; Gisewhite, D.; Kalinsky, A.; Esmail, A.; Burgmayer, S.J.N. Solvent-Dependent Pyranopterin Cyclization in Molybdenum Cofactor Model Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 8214–8222.

- Williams, B.R.; Fu, Y.C.; Yap, G.P.A.; Burgmayer, S.J.N. Structure and Reversible Pyran Formation in Molybdenum Pyranopterin Dithiolene Models of the Molybdenum Cofactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19584–19587.

- Ceccaldi, P.; Rendon, J.; Leger, C.; Toci, R.; Guigliarelli, B.; Magalon, A.; Grimaldi, S.; Fourmond, V. Reductive activation of E. coli respiratory nitrate reductase. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 1055–1063.

- George, G.N.; Hilton, J.; Temple, C.; Prince, R.C.; Rajagopalan, K.V. Structure of the Molybdenum Site of Dimethyl Sulfoxide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1256–1266.

- Jacques, J.G.J.; Fourmond, V.; Arnoux, P.; Sabaty, M.; Etienne, E.; Grosse, S.; Biaso, F.; Bertrand, P.; Pignol, D.; Leger, C.; et al. Reductive activation in periplasmic nitrate reductase involves chemical modifications of the Mo-cofactor beyond the first coordination sphere of the metal ion. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 2014, 1837, 277–286.

- Wu, S.Y.; Rothery, R.A.; Weiner, J.H. Pyranopterin Coordination Controls Molybdenum Electrochemistry in Escherichia coli Nitrate Reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 25164–25173.

- Inscore, F.E.; McNaughton, R.; Westcott, B.L.; Helton, M.E.; Jones, R.; Dhawan, I.K.; Enemark, J.H.; Kirk, M.L. Spectroscopic evidence for a unique bonding interaction in oxo-molybdenum dithiolate complexes: Implications for sigma electron transfer pathways in the pyranopterin dithiolate centers of enzymes. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 1401–1410.

- Stein, B.W.; Yang, J.; Mtei, R.; Wiebelhaus, N.J.; Kersi, D.K.; LePluart, J.; Lichtenberger, D.L.; Enemark, J.H.; Kirk, M.L. Vibrational Control of Covalency Effects Related to the Active Sites of Molybdenum Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14777–14788.

- Inscore, F.E.; Knottenbelt, S.Z.; Rubie, N.D.; Joshi, H.K.; Kirk, M.L.; Enemark, J.H. Understanding the origin of metal-sulfur vibrations in an oxo-molybdenurn dithiolene complex: Relevance to sulfite oxidase. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 967.

- McNaughton, R.L.; Helton, M.E.; Rubie, N.D.; Kirk, M.L. The oxo-gate hypothesis and DMSO reductase: Implications for a psuedo-sigma bonding interaction involved in enzymatic electron transfer. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 4386.

- Winkler, J.R.; Gray, H.B. Electronic Structures of Oxo-Metal Ions. In Molecular Electronic Structures of Transition Metal Complexes I; Mingos, D.M.P., Day, P., Dahl, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 142, pp. 17–28.

- Helton, M.E.; Kirk, M.L. A model for ferricyanide-inhibited sulfite oxidase. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 4384–4385.

- Yang, J.; Rothery, R.; Sempombe, J.; Weiner, J.H.; Kirk, M.L. Spectroscopic Characterization of YedY: The Role of Sulfur Coordination in a Mo(V) Sulfite Oxidase Family Enzyme Form. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15612–15614.

- Paudel, J.; Pokhrel, A.; Kirk, M.L.; Li, F.F. Remote Charge Effects on the Oxygen-Atom-Transfer Reactivity and Their Relationship to Molybdenum Enzymes. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 2054–2068.

- Kroneck, P.M.H. Acetylene hydratase: A non-redox enzyme with tungsten and iron-sulfur centers at the active site. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 21, 29–38.

- Liao, R.Z.; Thiel, W. On the Effect of Varying Constraints in the Quantum Mechanics Only Modeling of Enzymatic Reactions: The Case of Acetylene Hydratase. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 3954–3961.

- Liao, R.Z.; Yu, J.G.; Himo, F. Mechanism of tungsten-dependent acetylene hydratase from quantum chemical calculations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22523.

- Seiffert, G.B.; Ullmann, G.M.; Messerschmidt, A.; Schink, B.; Kroneck, P.M.; Einsle, O. Structure of the non-redox-active tungsten/ enzyme acetylene hydratase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3073–3077.

- Mtei, R.P.; Perera, E.; Mogesa, B.; Stein, B.; Basu, P.; Kirk, M.L. A Valence Bond Description of Dizwitterionic Dithiolene Character in an Oxomolybdenum-Bis(dithione) Complex. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 5467–5470.

- Hsu, J.K.; Bonangelino, C.J.; Kaiwar, S.P.; Boggs, C.M.; Fettinger, J.C.; Pilato, R.S. Direct conversion of alpha-substituted ketones to metallo-1,2-enedithiolates. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 4743–4751.

- Gisewhite, D.R.; Nagelski, A.L.; Cummins, D.C.; Yap, G.P.A.; Burgmayer, S.J.N. Modeling Pyran Formation in the Molybdenum Cofactor: Protonation of Quinoxalyl–Dithiolene Promoting Pyran Cyclization. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 5134–5144.

- Pilato, R.S.; Eriksen, K.A.; Greaney, M.A.; Stiefel, E.I.; Goswami, S.; Kilpatrick, L.; Spiro, T.G.; Taylor, E.C.; Rheingold, A.L. Model Complexes for Molybdopterin-Containing Enzymes: Preparation and Crystallographic Characterization of a Molybdenum-Ene-1-Perthiolate-2-Thiolate (Trithiolate) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 9372–9374.

- Pilato, R.S.; Eriksen, K.; Greaney, M.A.; Gea, Y.; Taylor, E.C.; Goswami, S.; Kilpatrick, L.; Spiro, T.G.; Rheingold, A.L.; Stiefel, E.I. Pterins, Quinoxalines, and Metallo-ene-dithiolates—Synthetic Approach to the Molybdenum Cofactor. ACS Symp. Ser. 1993, 535, 83–97.

- Dinsmore, A.; Birks, J.H.; Garner, C.D.; Joule, J.A. Synthesis of (eta(5)-cyclopentadienyl)-1-(4-benzyloxycarbonyl-3;4-dihydroquin oxalin-2-yl)ethene-1;2-dithiolatocobalt(III) and (eta(5)-cyclopentadienyl)-1-ethene-1;2-dithiolatocobalt(III). J. Chem. Soc. -Perkin Trans. 1 1997, 1997, 801–807.

- Hille, R.; Massey, V. Studies on the Oxidative Half-Reaction of Xanthine Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 9090–9095.

- Jones, R.M.; Inscore, F.E.; Hille, R.; Kirk, M.L. Freeze-Quench Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectroscopic Study of the “Very Rapid” Intermediate in Xanthine Oxidase. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 4963–4970.

- Hille, R.; Anderson, R.F. Coupled Electron/Proton Transfer in Complex Flavoproteins: Solvent Kinetic Isotope Effect Studies of Electron Transfer in Xanthine Oxidase and Trimethylamine Dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 31193–31201.

- Matz, K.G.; Mtei, R.P.; Leung, B.; Burgmayer, S.J.N.; Kirk, M.L. Noninnocent Dithiolene Ligands: A New Oxomolybdenum Complex Possessing a Donor Acceptor Dithiolene Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7830–7831.

- Matz, K.G.; Mtei, R.P.; Rothstein, R.; Kirk, M.L.; Burgmayer, S.J.N. Study of Molybdenum(4+) Quinoxalyldithiolenes as Models for the Noninnocent Pyranopterin in the Molybdenum Cofactor. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 9804–9815.

- Yang, J.; Mogesa, B.; Basu, P.; Kirk, M.L. Large Ligand Folding Distortion in an Oxomolybdenum Donor Acceptor Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 785–793.

More