Many CRISPR–Cas systems have been used as a backbone for the development of potent research tools, with Cas9 being the most widespread. While most of the utilized systems are DNA-targeting, recently more and more attention is being gained by those that target RNA. Their ability to specifically recognize a given RNA sequence in an easily programmable way makes them ideal candidates for developing new research tools.

This article is associated with review article "RNA-Targeting CRISPR–Cas Systems and Their Applications" published in MDPI International Journal of Molecular Sciences" on 7 February 2020 by Michał Burmistrz, Kamil Krakowski and Agata Krawczyk-Balska. Mentioned article presents a comprehensive and concise review of a current knowledge on RNA-targeting CRISPR/Cas systems. These systems gain a lot of attention recently as they not only shed a new light on biology of prokaryotes but also are considered as a valuable extension for CRISPR/Cas toolbox. Mechanism of each type is described, including both crRNA maturation and interference stages. In addition to that, paper lists the applications for each of presented CRISPR/Cas types.

- CRSIPR/Cas

- Cas9

- Cas13

- RNA

- Cmr

- Csm

1. Introorduction

The mechanism of CRISPR–Cas systems consists of three phases: adaptation, maturation, and interference. During the adaptation phase, new spacers are incorporated into the CRISPR array into its leader end [6]. During the maturation phase the CRISPR array is transcribed. The resulting transcript called pre-CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) is further processed into a set of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) molecules, each containing a single spacer flanked by fragments of a repeat sequence [7][8][9][10][11][12]. Subsequently, crRNAs are incorporated into ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes together with Cas proteins. RNP complexes scan nucleic acids searching for a sequence complementary to that encoded by crRNA [13]. Recognition of such a sequence triggers the interference phase that leads to degradation of a recognized nucleic acid [14][15][16].

Discovery of the CRISPR–Cas systems has revolutionized modern molecular biology. Due to their unique mechanism, they possess several features highly desirable for potential tools in this field. First of all, they are highly specific in terms of recognized sequence. Furthermore, this specificity can be easily altered by modifying the sequence coding the crRNA. The modular structure of the CRISPR locus makes these modifications even easier. The range of applications for CRISPR–Cas systems can be further expanded by modifying the Cas proteins themselves

[17]. Most of the CRISPR–Cas systems described to date are those targeting DNA sequences. In recent years several new types of CRISPR–Cas systems targeting RNA were discovered, paving the way for the development of new tools for research and biotechnology." [18]

2. Overview of RNA-Targeting CRISPR–Cas Systems

2.1. Type III (Cmr/Csm) Systems

Type III (Cmr/Csm) Systems

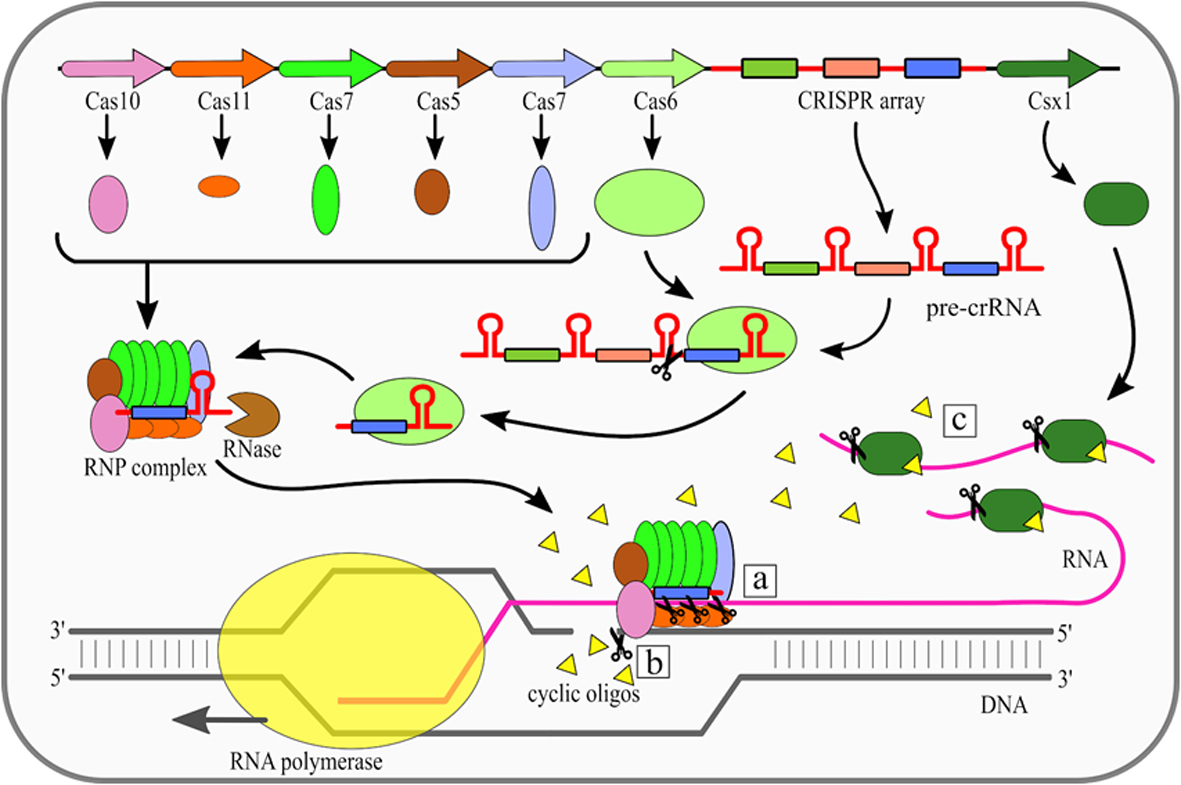

The effector complexes of type III systems consist of multiple subunits and thus they belong to the class 1 CRISPR-Cas systems. Maturation of crRNAs in majority of type III systems includes two stages: first pre-crRNA is cleaved by Cas6, then resulting crRNAs are further trimmed in a mechanism that has not been fully described yet. A unique feature of type III CRISPR-Cas systems is that they use three nuclease activities (Fig. 1). The first one is a sequence specific RNA cleavage performed by the Cas7, which is a integral part of the RNP complex [19][20] (Fig. 1a). The second nuclease activity of this type is Cas10-dependent non-specific ssDNA cleavage [21]. This activity requires transcription to occur. Once the RNA polymerase opens the DNA double helix it exposes the antisense strand. Digestion of the antisense strand is triggered by the complementarity between crRNA and the targeted RNA [22]. The third nuclease activity of type III CRISPR/Cas systems is a non-specific RNA degradation. This activity also depends on Cas10, but its mechanism is different. In this case so called palm domain of Cas10 is involved in conversion of ATP into cyclic oligoadenylates [23][24]. Conversion is non constitutive and it is triggered by binding of the RNP complex with targeted RNA with simultaneous non-complementarity between crRNA handle and targeted RNA. These cyclic oligoadenylates allosterically activate the Csm6/Csx1 (depending on a given system subtype) proteins, which are responsible for RNA cleavage, yet they are not incorporated into RNP complexes themselves.

Figure 1. Mechanism of the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)–CRISPR-associated (Cas) type III (Csm/Cmr) system. Cas6 endoribonuclease cleaves pre-CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) within the repeat region. Subsequently, the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is assembled, while the 3' end of crRNA is trimmed by an unknown nuclease. There are three nuclease activities of the RNP complex: (a) specific RNA cleavage, (b) non-specific ssDNA cleavage, (c) non-specific RNA degradation. [18]

2.2. Type VI (Cas13) Systems

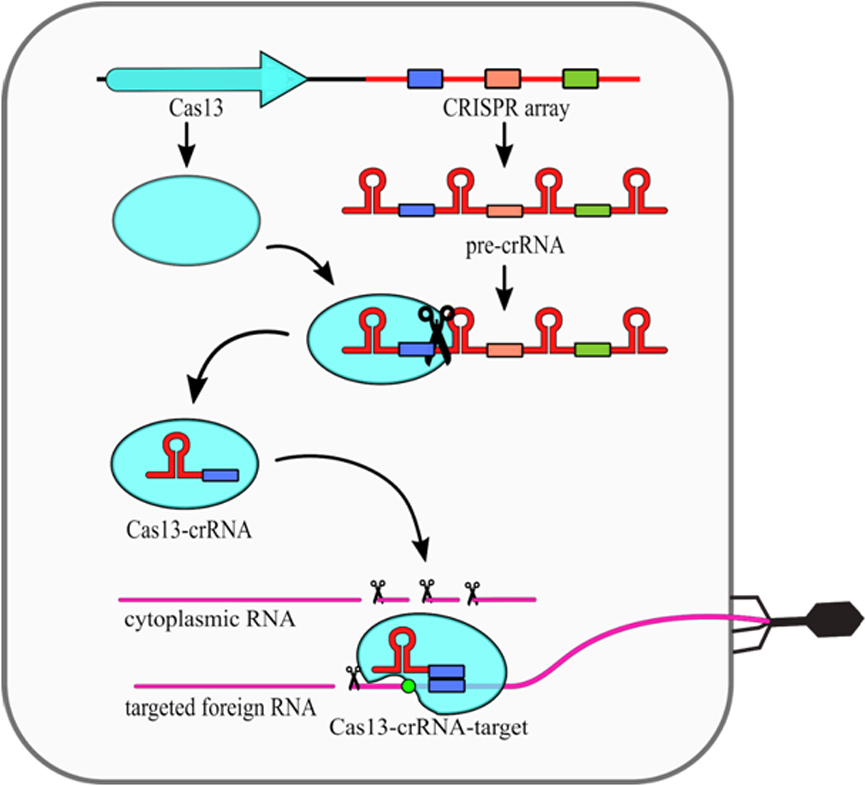

The type VI CRISPR-Cas systems present a relatively simple structure, as they require only one Cas13 protein and crRNA molecule (Fig. 2). Cas13 performs the primary processing of pre-crRNA itself [25]. Secondary crRNA processing is performed presumably by other host nucleases. What is interesting, it was shown that the type VI nucleolytic activy can be maintained even when non processed crRNA molecules are used [26]. The intereference mechanism of this type includes conformational change of Cas13 protein, which is induced by compelementarity between crRNA and targeted ssRNA. Upon that change, two HEPN domains are moved closed together to form a single catalytic site. As this site is exposed outside of the Cas13 it cleaves not only targeted ssRNA, but also any other ssRNA in the vicinity. This phenomenon is known as a collateral damage of Cas13 system [17].

FiguThe effector comple 2. Mechanism of the xes of type III systems consist of multiple subunits and thus they belong to the class 1 CRISPR–Cas13 (type VI)-Cas systems. Maturation of crRNAs in majority of type III system. The CRISPR array is transs includes two stages: first pre-crRNA is cleaved by Cas6, then resulting crRNAs are further trimmed in a mechanism that has not been fully described into a long preyet. A unique feature of type III CRISPR-Cas systems is that they use three nuclease activities (Fig. 1). The first one is a sequence specific RNA cleavage performed by the Cas7, which is a integral part of the RNP complex [19][20] (Fig. 1a). The second nuclease activity of this type is Cas10-dependent non-specrRNA ific ssDNA cleavage [21]. This activity requires transcript, which is subsequently processed into mature crRNAion to occur. Once the RNA polymerase opens the DNA double helix it exposes the antisense strand. Digestion of the antisense strand is triggered by the complementarity between crRNA and the targeted RNA [22]. The third nuclease by Cas13 protein. The crRNA-Cas13 complex scansactivity of type III CRISPR/Cas systems is a non-specific RNA degradation. This activity also depends on Cas10, but its mechanism is different. In this case so called palm domain of Cas10 is involved in conversion of ATP into cyclic oligoadenylates [23][24]. thConve ssRNA searching for protospacer. Crsion is non constitutive and it is triggered by binding of the RNP complex with targeted RNA with simultaneous non-complementarity between crRNA and the protospacer sequence together withhandle and targeted RNA. These cyclic oligoadenylates allosterically activate the Csm6/Csx1 (depending on a given system subtype) proteins, which are responsible for RNA cleavage, yet they are not incorporated into RNP complexes themselves.

Figure 1. Mechanism of the pClusteresence of Protospacer Flanking Sequence (PFS) (green circle) induces conformational changes ofd Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)–CRISPR-associated (Cas) type III (Csm/Cmr) system. Cas6 endoribonuclease cleaves pre-CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) within the repeat region. Subsequently, the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is assembled, while the 3' end of crRNA is trimmed by an unknown nuclease. There are three nuclease activities of the RNP complex: (a) specific RNA cleavage, (b) non-specific ssDNA cleavage, (c) non-specific RNA degradation. [18]

Type VI (Cas13) Systems.

The type VI CRISPR-Cas13, which results in higher eukaryotess systems present a relatively simple structure, as they require only one Cas13 protein and crRNA molecule (Fig. 2). Cas13 performs the primary processing of pre-crRNA itself [25]. Secondand prokaryotesry crRNA processing is performed presumably by other host nucleotide binding (HEPN) domainsases. What is interesting, it was shown that the type VI nucleolytic activation any can be maintained even when non processed crRNA molecules are used t[26]. The ir displacement to the protein surface. This results in nonspecific RNA cleavage.ntereference mechanism of this type includes conformational change of Cas13 protein, which is induced by compelementarity between crRNA and targeted ssRNA. Upon that change, two HEPN domains are moved closed together to form a single catalytic site. As this site is exposed outside of the Cas13 it cleaves not only targeted ssRNA, but also any other ssRNA in the vicinity. This phenomenon is known as a collateral damage of Cas13 system [1817].

2.3. Type II (Cas9) Systems

InFigure 2. addition toMechanism of the CRISPR array and Cas proteins type II CRISPR/Cas systems encode additional trans activating RNA (tracrRNA), which mediates interaction between crRNAs and Cas9. The primary processing of type II p–Cas13 (type VI) system. The CRISPR array is transcribed into a long pre-crRNAs is performed by RNase III [9]. Fragment of tracrRNA binds to a repeat sequence creating a duplex. This dulex is then cleaved by RNase III [8]. Sranscript, which is subsequently, this intermediatprocessed into mature crRNA is further trimmed by an unknown nucleases by Cas13 protein. The maturated crRNA:tracrRNA duplex is incorporated into Cas9. Similar to type III systems, Cas9 was shown to possess several nucleolytic activities (Figure. 3). The most common nuclease activity among type II systems is specific dsDNA cleavage (Figure. 3a). For some type II CRISPR/Cas systems additional nucleolytic directed against RNA have been described. In Francisella novicida typcrRNA-Cas13 complex scans the ssRNA searching for protospacer. Complementarity between crRNA and the protospacer sequence together with the presence of Protospacer Flanking Sequence (PFS) (green circle) induces II encodes addiconformational small RNA named scaRNAchanges of Cas13, which is supposed to replace crRNA in the RNP complex. This enable it to target RNA instead of DNA [27].results in higher eukaryotes and prokaryotes nucleotide binding (HEPN) Recent studies have shown that some of the type II CRISPR-Cas systems present natural nucleolytic activity against ssRNA targets. To date, this particular ssRNA targeting activity has beenomains activation and their displacement to the protein surface. This results in nonspecific RNA cleavage. described for [18]

Type II (Cas9) Systems

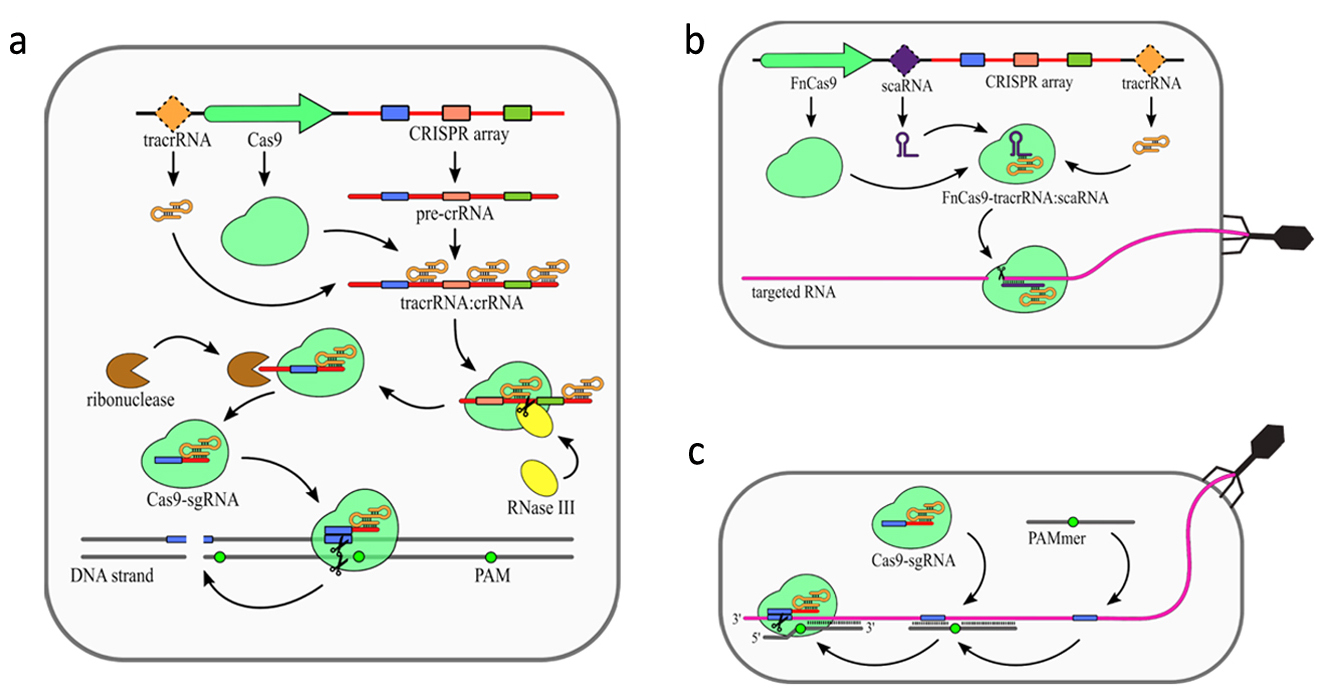

In addition to CRISPR array and Cas proteins type II CRISPR/Cas systems encode additional trans activating RNA (tracrRNA), which mediates interaction between crRNAs and Cas9. The primary processing of type II pre-crRNAs is performed by RNase III [9]. Fragment of tracrRNA binds to a repeat sequence creating a duplex. This dulex is then cleaved by RNase III [8]. Subsequently, this intermediate crRNA is further trimmed by an unknown nuclease. The maturated crRNA:tracrRNA duplex is incorporated into Cas9. Similar to type III systems, Cas9 was shown to possess several nucleolytic activities (Fig. 3). The most common nuclease activity among type II systems is specific dsDNA cleavage (Fig. 3a). For some type II CRISPR/Cas systems additional nucleolytic directed against RNA have been described. In Francisella novicida type II encodes additional small RNA named scaRNA, which is supposed to replace crRNA in the RNP complex. This enable it to target RNA instead of DNA [27]. Recent studies have shown that some of the type II CRISPR-Cas systems present natural nucleolytic activity against ssRNA targets. To date, this particular ssRNA targeting activity has been described for

Staphylococcus aureus

[28]

,

Campylobacter jejuni

[29]

, and

Neisseria meningitides

[30]

. However, still very little is known about mechanistic details of this activity.

Figure 3. Mechanism of the CRISPR–Cas9 (type II) system. (a) DNA targeting CRISPR array transcription generates pre-crRNA. Maturation of the crRNAs is dependent on trans activating RNA (tracrRNA), which is partially complementary to the repeat sequences in the pre-crRNA resulting in tracrRNA/crRNA duplex formation. Those duplexes are bound and stabilized by Cas9 protein. Host RNase III is then recruited to cleave pre-crRNA into units containing single spacer sequences. Further trimming of the crRNAs is performed by unknown ribonuclease. The complex of Cas9 and single guide RNA (sgRNA: tracrRNA–crRNA) scans DNA until it finds a Protospacer-Associated Motif (PAM) sequence. The DNA strand is then unwound, allowing sgRNA for complementarity verification. Positive recognition results in cleavage of both DNA strands. (b) scaRNA-dependent RNA targeting was observed for Cas9 from Francisella novicida (FnCas9). Small CRISPR/Cas-associated RNA (scaRNA) hybridizes with tracrRNA to form heteroduplex that binds Cas9 protein. FnCas9–tracrRNA/scaRNA complex targets RNA partially complementary to scaRNA sequence. The precise mechanism of FnCas9 remains unclear. (c) PAM-presenting oligonucleotide (PAMer)-dependent RNA targeting Functional Cas9–sgRNA complex is able to target RNA in the presence of PAMmers–short DNA oligonucleotides containing PAM. When the PAMmer is bound to target RNA, the Cas9–sgRNA complex is able

to recognize and cleave the RNA as long as complementarity between sgRNA and targeted RNA is maintained. [18]

4. Applications Based on RNA-Targeting CRISPR–Cas Systems

Applications Based on RNA-Targeting CRISPR–Cas Systems

Table 1. Applications based on RNA-targeting CRISPR-Cas systems. [18] modified.

| Application | CRISPR-Cas type (technology name) | Reference |

|

RNA knockdown |

Cas9 |

[28] |

|

Cas13a/b/c |

[31][32][33][25][34] | |

|

Csm/Cmr |

[35][36] | |

|

Cas13d (CasRx) |

[37] | |

|

RNA imagingand tracking |

dCas9 |

[38] |

|

dCas13a |

[33] | |

|

RNA editing |

Cas13b (REPAIR) |

[39] |

|

nucleic acid detection |

Cas13a (SHERLOCKv1) |

[40] |

|

Cas13 + Csm6 (SHERLOCKv2) |

[41] | |

|

splicing alteration |

dCas13d (dCasRx) |

[35] |

|

resistance againstRNA viruses |

FnCas9 |

[42][43] |

|

Cas13a |

[19] | |

|

induction of apoptosis |

Cas13a |

[17] |

|

regulation of gene expression |

Cas13b |

[19] |

|

specific RNA isolation |

dCas9 |

[44] |

|

elimination of repetitive sequences |

Cas9 |

[20] |

References

- Kira S. Makarova; Nick V. Grishin; Svetlana A. Shabalina; Yuri I. Wolf; Eugene V. Koonin; A putative RNA-interference-based immune system in prokaryotes: computational analysis of the predicted enzymatic machinery, functional analogies with eukaryotic RNAi, and hypothetical mechanisms of action. Biology Direct 2006, 1, 7-7, 10.1186/1745-6150-1-7.

- Stern, A.; Keren, L.; Wurtzel, O.; Amitai, G.; Sorek, R. Self-targeting by CRISPR: gene regulation or autoimmunity? Trends Genet. TIG 2010, 26, 335–340.

- Reuben McKay Vercoe; James T. Chang; Ron Leonard Dy; Corinda Taylor; Tamzin Gristwood; James S. Clulow; Corinna Richter; Rita Przybilski; Andrew Robert Pitman; Peter C Fineran; Cytotoxic Chromosomal Targeting by CRISPR/Cas Systems Can Reshape Bacterial Genomes and Expel or Remodel Pathogenicity Islands. PLOS Genetics 2013, 9, e1003454, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003454.

- Ruud. Jansen; Jan. D. A. Van Embden; Wim. Gaastra; Leo. M. Schouls; Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Molecular Microbiology 2002, 43, 1565-1575, 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x.

- Ido Yosef; Moran G. Goren; Udi Qimron; Proteins and DNA elements essential for the CRISPR adaptation process in Escherichia coli.. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40, 5569-76, 10.1093/nar/gks216.

- Rodolphe Barrangou; C. Fremaux; H. Deveau; M. Richards; P. Boyaval; Sylvain Moineau; D. A. Romero; Philippe Horvath; CRISPR Provides Acquired Resistance Against Viruses in Prokaryotes. Science 2007, 315, 1709-1712, 10.1126/science.1138140.

- Judith Reeks; James H. Naismith; Malcolm F White; CRISPR interference: a structural perspective. Biochemical Journal 2013, 453, 155-166, 10.1042/bj20130316.

- Elitza Deltcheva; Krzysztof Chylinski; Cynthia M. Sharma; Karine Gonzales; Yanjie Chao; Zaid A. Pirzada; Maria R. Eckert; Jörg Vogel; Emmanuelle Charpentier; CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 2011, 471, 602-7, 10.1038/nature09886.

- Martin Jinek; Krzysztof Chylinski; Ines Fonfara; Michael Hauer; Jennifer A. Doudna; Emmanuelle Charpentier; A Programmable Dual-RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816-821, 10.1126/science.1225829.

- Caryn R. Hale; Sonali Majumdar; Joshua Elmore; Neil Pfister; Mark Compton; Sara Olson; Alissa M. Resch; Claiborne V. C. Glover; Brenton R. Graveley; Michael P Terns; Michael P Terns; Essential Features and Rational Design of CRISPR RNAs that Function with the Cas RAMP Module Complex to Cleave RNAs. Molecular Cell 2012, 45, 292-302, 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.023.

- Jing Zhang; Christophe Rouillon; Melina Kerou; Judith Reeks; Kim Brügger; Shirley Graham; Julia Reimann; Giuseppe Cannone; Huanting Liu; Sonja-Verena Albers; James H. Naismith; Laura Spagnolo; Malcolm F White; Structure and Mechanism of the CMR Complex for CRISPR-Mediated Antiviral Immunity. Molecular Cell 2012, 45, 303-13, 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.013.

- Michal Burmistrz; Jose Ignacio Rodriguez Martinez; Daniel Krochmal; Dominika Staniec; Krzysztof Pyrc; Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR) RNAs in the Porphyromonas gingivalis CRISPR-Cas I-C System. Journal of Bacteriology 2017, 199, e00275-17, 10.1128/JB.00275-17.

- Ekaterina Semenova; Matthijs M. Jore; Kirill A. Datsenko; Anna Semenova; Edze R. Westra; Barry Wanner; John Van Der Oost; Stan J. J. Brouns; Konstantin Severinov; Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 10098-10103, 10.1073/pnas.1104144108.

- Matthijs M Jore; Magnus Lundgren; Esther Van Duijn; Jelle B Bultema; Edze R. Westra; Sakharam P Waghmare; Blake Wiedenheft; Ümit Pul; Reinhild Wurm; Rolf Wagner; Marieke R Beijer; Arjan Barendregt; Kaihong Zhou; Ambrosius P. Snijders; Mark J. Dickman; Jennifer A Doudna; Egbert J Boekema; Albert J. R. Heck; John Van Der Oost; Stan J J Brouns; Structural basis for CRISPR RNA-guided DNA recognition by Cascade. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2011, 18, 529-536, 10.1038/nsmb.2019.

- Michael Spilman; Alexis Cocozaki; Caryn Hale; Yaming Shao; Nancy Ramia; Rebeca Terns; Michael Terns; Hong Li; Scott M. Stagg; Structure of an RNA Silencing Complex of the CRISPR-Cas immune system. Molecular Cell 2013, 52, 146-52, 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.008.

- Blake Wiedenheft; Gabriel C. Lander; Kaihong Zhou; Matthijs M. Jore; Stan J. J. Brouns; John Van Der Oost; Jennifer A. Doudna; Eva Nogales; Structures of the RNA-guided surveillance complex from a bacterial immune system.. Nature 2011, 477, 486-489, 10.1038/nature10402.

- Omar O. Abudayyeh; Jonathan S. Gootenberg; Silvana Konermann; Julia Joung; Ian M. Slaymaker; David B.T. Cox; Sergey Shmakov; Kira S. Makarova; Ekaterina Semenova; Leonid Minakhin; Konstantin Severinov; Aviv Regev; Eric S. Lander; Eugene V. Koonin; Feng Zhang; C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. null 2016, null, 054742, 10.1101/054742.

- Michał Burmistrz, Kamil Krakowski, Agata Krawczyk-Balska . RNA-Targeting CRISPR-Cas Systems and Their Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 7;21(3). pii: E1122. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031122.

- Silvana Konermann; Peter Lotfy; Nicholas J. Brideau; Jennifer Oki; Maxim N. Shokhirev; Patrick Hsu; Transcriptome Engineering with RNA-Targeting Type VI-D CRISPR Effectors. Cell 2018, 173, 665-676.e14, 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.033.

- Ranjan Batra; David A. Nelles; Elaine Pirie; Steven` Blue; Ryan J. Marina; Harrison Wang; Isaac A. Chaim; James D. Thomas; Nigel Zhang; Vu Nguyen; et al.Stefan AignerSebastian MarkmillerGuangbin XiaKevin D. CorbettMaurice SwansonGene W. Yeo Elimination of Toxic Microsatellite Repeat Expansion RNA by RNA-Targeting Cas9. Cell 2017, 170, 899-912.e10, 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.010.

- Michael Estrella; Fang-Ting Kuo; Scott Bailey; RNA-activated DNA cleavage by the Type III-B CRISPR–Cas effector complex. Genes & Development 2016, 30, 460-470, 10.1101/gad.273722.115.

- Migle Kazlauskiene; Gintautas Tamulaitis; Georgij Kostiuk; Česlovas Venclovas; Virginijus Siksnys; Spatiotemporal Control of Type III-A CRISPR-Cas Immunity: Coupling DNA Degradation with the Target RNA Recognition. Molecular Cell 2016, 62, 295-306, 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.024.

- Ole Niewoehner; Carmela Garcia-Doval; Jakob T. Rostøl; Christian Berk; Frank Schwede; Laurent Bigler; Jonathan Hall; Luciano A. Marraffini; Martin Jinek; Type III CRISPR–Cas systems produce cyclic oligoadenylate second messengers. Nature 2017, 548, 543-548, 10.1038/nature23467.

- Guillermo Montoya; Kazlauskiene M; Kostiuk G; Venclovas Č; Tamulaitis G; Siksnys V; Faculty of 1000 evaluation for A cyclic oligonucleotide signaling pathway in type III CRISPR-Cas systems.. F1000 - Post-publication peer review of the biomedical literature 2017, 357, , 10.3410/f.727762357.793538304.

- Lei Qi; Shmakov S; Abudayyeh Oo; Makarova Ks; Wolf Yi; Gootenberg Js; Semenova E; Minakhin L; Joung J; Konermann S; Severinov K; Zhang F; Koonin Ev; Faculty of 1000 evaluation for Discovery and Functional Characterization of Diverse Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems.. F1000 - Post-publication peer review of the biomedical literature 2017, 60, , 10.3410/f.725924909.793532243.

- Alexandra Seletsky; Mitchell O'connell; David Burstein; Gavin J. Knott; Jennifer A. Doudna; RNA Targeting by Functionally Orthogonal Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas Enzymes.. Molecular Cell 2017, 66, 373-383.e3, 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.04.008.

- Timothy R Sampson; Sunil D. Saroj; Anna Llewellyn; Yih-Ling Tzeng; David S. Weiss; A CRISPR/Cas system mediates bacterial innate immune evasion and virulence. Nature 2013, 497, 254-257, 10.1038/nature12048.

- Steven C Strutt; Rachel M Torrez; Emine Kaya; Oscar A Negrete; Jennifer A. Doudna; RNA-dependent RNA targeting by CRISPR-Cas9. eLife 2018, 7, , 10.7554/eLife.32724.

- Gaurav Dugar; Ryan T. Leenay; Sara K. Eisenbart; Thorsten Bischler; Belinda U. Aul; Chase L. Beisel; Cynthia M. Sharma; CRISPR RNA-Dependent Binding and Cleavage of Endogenous RNAs by the Campylobacter jejuni Cas9. Molecular Cell 2018, 69, 893-905.e7, 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.032.

- Beth A. Rousseau; Zhonggang Hou; Max J. Gramelspacher; Yan Zhang; Programmable RNA Cleavage and Recognition by a Natural CRISPR-Cas9 System from Neisseria meningitidis. Molecular Cell 2018, 69, 906-914.e4, 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.025.

- Michał Burmistrz; Krzysztof Pyrc; CRISPR-Cas Systems in Prokaryotes. Polish Journal of Microbiology 2015, 64, 193-202, 10.5604/01.3001.0009.2114.

- Hakim Manghwar; Keith Lindsey; Xianlong Zhang; Shuangxia Jin; CRISPR/Cas System: Recent Advances and Future Prospects for Genome Editing.. Trends in Plant Science 2019, 24, 1102-1125, 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.09.006.

- Sergey Brezgin; Anastasiya Kostyusheva; Dmitry Kostyushev; Vladimir Chulanov; Dead Cas Systems: Types, Principles, and Applications.. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 6041, 10.3390/ijms20236041.

- Solmaz Khosravi; Takayoshi Ishii; Steven Dreissig; Andreas Houben; Application and prospects of CRISPR/Cas9-based methods to trace defined genomic sequences in living and fixed plant cells. Chromosome Research 2019, 28, 7-17, 10.1007/s10577-019-09622-0.

- Maria Teresa Valenti; Michela Serena; Luca Dalle Carbonare; Donato Zipeto; CRISPR/Cas system: An emerging technology in stem cell research. World Journal of Stem Cells 2019, 11, 937-956, 10.4252/wjsc.v11.i11.937.

- Mehdi Banan; Recent advances in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-ins in mammalian cells. Journal of Biotechnology 2020, 308, 1-9, 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2019.11.010.

- Manzoor N. Khanzadi; Abid Ali Khan; CRISPR/Cas9: Nature's gift to prokaryotes and an auspicious tool in genome editing. Zeitschrift für allgemeine Mikrobiologie 2019, 60, 91-102, 10.1002/jobm.201900420.

- Ziga ZebeC; Andrea Manica; Jing Zhang; Malcolm F White; Christa Schleper; CRISPR-mediated targeted mRNA degradation in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus.. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, 5280-8, 10.1093/nar/gku161.

- Sergey Shmakov; Aaron Smargon; David Scott; David Cox; Neena Pyzocha; Winston Yan; Omar O. Abudayyeh; Jonathan S. Gootenberg; Kira S. Makarova; Yuri I. Wolf; Konstantin Severinov; Feng Zhang; Eugene V. Koonin; Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR–Cas systems. Nature Reviews Genetics 2017, 15, 169-182, 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.184.

- Liang Liu; Xueyan Li; Jun Ma; Zongqiang Li; Lilan You; Jiuyu Wang; Min Wang; Xinzheng Zhang; Yanli Wang; The Molecular Architecture for RNA-Guided RNA Cleavage by Cas13a. Cell 2017, 170, 714-726.e10, 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.050.

- Kira S. Makarova; Vivek Anantharaman; L. Aravind; Eugene V. Koonin; Live virus-free or die: coupling of antivirus immunity and programmed suicide or dormancy in prokaryotes. Biology Direct 2012, 7, 40-40, 10.1186/1745-6150-7-40.

- Martin Jinek; Fuguo Jiang; David W. Taylor; Samuel H. Sternberg; Emine Kaya; Enbo Ma; Carolin Anders; Michael Hauer; Kaihong Zhou; Steven Lin; Matias Kaplan; Anthony T. Iavarone; Emmanuelle Charpentier; Eva Nogales; Jennifer A. Doudna; Structures of Cas9 Endonucleases Reveal RNA-Mediated Conformational Activation. Science 2014, 343, 1247997-1247997, 10.1126/science.1247997.

- H. Travis Ichikawa; John C. Cooper; Leja Lo; Jason Potter; Michael P Terns; Michael P Terns; Programmable type III-A CRISPR-Cas DNA targeting modules. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0176221, 10.1371/journal.pone.0176221.

- Rodolphe Barrangou; Charles A. Gersbach; Expanding the CRISPR Toolbox: Targeting RNA with Cas13b. Molecular Cell 2017, 65, 582-584, 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.002.

- Silvana Konermann; Peter Lotfy; Nicholas J. Brideau; Jennifer Oki; Maxim N. Shokhirev; Patrick Hsu; Transcriptome Engineering with RNA-Targeting Type VI-D CRISPR Effectors. Cell 2018, 173, 665-676.e14, 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.033.

- Rodolphe Barrangou; Charles A. Gersbach; Expanding the CRISPR Toolbox: Targeting RNA with Cas13b. Molecular Cell 2017, 65, 582-584, 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.002.