DNA alkyltransferase and alkyltransferase-like family proteins are responsible for the repair of highly mutagenic and cytotoxic O6-alkylguanine and O4-alkylthymine bases in DNA. Their mechanism involves binding to the damaged DNA and flipping the base out of the DNA helix into the active site pocket in the protein. Alkyltransferases then directly and irreversibly transfer the alkyl group from the base to the active site cysteine residue. In contrast, alkyltransferase-like proteins recruit nucleotide excision repair components for O6-alkylguanine elimination. One or more of these proteins are found in all kingdoms of life, and where this has been determined, their overall DNA repair mechanism is strictly conserved between organisms.

- DNA repair

- O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase

- alkylation damage

1. Introduction

Alkylation of DNA bases and phosphodiesters in the DNA backbone can arise from both endogenous and exogenous agents. The former seems predominantly to be due to the nitrosation of amine-containing compounds and the subsequent metabolic activation of alkylating species by mixed function oxidases [1]. The methyl donor, S-adenosylmethionine, might also contribute to endogenous DNA methylation [1]. Exogenous agents include, for example, some constituents of cigarette smoke and certain cancer chemotherapeutic agents, although recent evidence suggests that there is a wide range of alkylation damage types in DNA and hence a large spectrum of environmental alkylating agents [2].

Alkylating agents can react with all the available N and O atoms in DNA [3][4][3, 4], and the relative amounts of the alkylation products are determined by the mass and the chemical nature of the alkylating species, which react by either SN1 or SN2 type nucleophilic substitution (reviewed in [1][3][4][5]). The simplest examples of SN1 agents are MNNG (N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine), the alkylnitrosoureas such as MNU (N-methyl-N-nitrosourea), nitrosamines such as NDMA (N,N-dimethylnitrosamine), and triazenes, including the cancer chemotherapeutic agents Temozolomide (TMZ) and Dacarbazine/DTIC. Examples of SN2 agents are MMS (methyl methanesulfonate) and DMS (dimethyl sulfate). In general, SN1 agents react more extensively with oxygen atoms, while SN2 agents attack mostly nitrogen atoms, but the relative amounts of the products are very different when comparing, for example, methylating and ethylating agents [6].

Several of the base alkylation products are mutagenic, clastogenic, and/or cytotoxic, while alkylated phosphodiesters in the DNA backbone have not been reported to have significant adverse biological effects. The most highly mutagenic alkylation products are the O6-alkylguanines and O4-alkylthymines. During replication, the former result in the mis-incorporation of thymine leading to G>A transition mutations, and the latter result in the mis-incorporation of guanine leading to T>C transition mutations [7][8][9]. O6-alkylguanines are also highly cytotoxic because the post-replication mispairs trigger futile rounds of DNA mismatch repair, resulting in single-strand gaps, replication fork collapse, and double-strand break formation, which ultimately leads to cell death [4][10][11][12].

O6-alkylguanines and O4-alkylthymines are repaired by the O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferases (AGTs, human version also known as O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase, MGMT). AGTs undertake the removal of alkyl groups attached to the O6 position of guanines and the O4 position of thymines in an autoinactivating (“suicide”) irreversible reaction that requires no cofactors and involves the transfer of the alkyl group to a cysteine residue in the active site pocket of AGT (as explained in detail below, section 4).

2. A Brief History of DNA Alkylation Damage and Repair

The history of research on DNA alkylating agents goes as far back as the early 1940s, when the cytotoxicity of mustard gas was exploited during world war II as a chemical weapon, but also investigated for uses in the then newly evolving field of cancer chemotherapy [13][14]. Between 1946 and 1948, interactions of alkylating nitrogen mustards with DNA bases and the DNA phosphate backbone were first reported [15][16][17]. The 1960s then saw a number of studies comparing the cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of different alkylating agents and relating these to the chemical modifications they generated in DNA [18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]. In the early studies, the predominant lesions found in DNA were the N7-alkylguanines [18][19][20][21][23] followed by the less abundant N3-alkyladenines [20][22][26]. It was subsequently shown that these lesions are targets of the Base Excision Repair pathway (BER). The highly mutagenic and cytotoxic methylation of the O6 position of guanine and the O4 position of thymine, the target lesions of the DNA alkyltransferases, were first reported in 1969 [27] and 1973 [28], respectively, as products of the methylating agent N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU).

The initial observations of the capability of cells to recover from the toxic effects of alkylation damage in DNA in the mid to late sixties [22][29] suggested that cells may possess protein systems to actively repair DNA alkyl lesions. Over the next decades, the versatility and complexity of the mechanisms that recognise and repair the majority of DNA alkylation damages have gradually been established in prokaryotes, archaea, and eukaryotes. They include, BER, Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER), DNA Mismatch Repair (MMR) and damage reversal.

3. The Adaptive Response

In the 1970s, it was discovered that exposure of E. coli to low doses of the methylating agent MNNG increases resistance to a subsequent higher dose of this agent [30][31]. This phenomenon, not related to the SOS response in E. coli, became known as the adaptive response and is regulated by the ada gene. While O6-alkylguanine repair is mediated by the carboxy-terminal (C-terminal) part of the Ada protein [32], the adaptive response to DNA alkylation damage is triggered by the amino-terminal (N-terminal) domain of Ada repairing one of the stereoisomers of the methylated phosphotriesters (MPTs) in the DNA backbone. Subsequently, in the late 1980s, a second O6-methylguanine repair activity was identified in E. coli and the encoding gene, which has extensive sequence homology to the C-terminal domain of ada, was named ogt [33]. In contrast to Ada, however, the gene product OGT demonstrated exclusively O6-alkylguanine (and O4-alkylthymine) repair activity and was shown to be constitutively expressed, i.e., without alkylation dependent upregulation [33][34].

MPT methyltransferase activity in Ada is conferred via four conserved cysteine residues in two consensus motifs (CRPSC and PCKRC) in the N-terminal domain that coordinate a Zn2+ ion [35]. For Ada from E. coli, methylation of C38 in the first of these two motifs has been shown to trigger a conformational switch in the protein [35]. This conformational change is also referred to as an electrostatic switch since cysteine alkylation upon MPT repair reduces the negative charge in the Zn2+ coordinating region, which vastly enhances its DNA binding affinity [35]. This activates it as a transcription factor that binds to the ada box in the promotor region of the ada gene, upregulating its expression [36][37], as well as that of other ada box genes involved in the adaptive response to alkylation damage, i.e., AlkA, AlkB, and AidB [38][39]. This response is also triggered to a lesser extent by ethylating agents, but as far as has been reported, not higher alkylating agents, implying that it has evolved as a response to intermittent increases in the levels of, predominantly, methylating agents in the E. coli environment.

The adaptive response to alkylation has since been found in a number of other prokaryotes, but also in different Aspergillus species, which demonstrate MPT repair-mediated adaptive responses [40][41]. In contrast to E. coli, where O6-alkylguanine repair and MPT repair-coupled transcription upregulation are both located in the same Ada protein [39], in Aspergillus, these two functions are on separate proteins [41]. A similar arrangement is found in the bacterium B. subtilis, which also contains two separate proteins for AGT and MPT alkyltransferase functions [41][42]. In addition to Aspergillus, Vicia faba has also been reported to show clastogenic adaptation by methylating agents [43], but the genes involved and the mechanism have yet to be defined. In contrast, higher eukaryotes including humans do not manifest an E. coli-like adaptive response to DNA alkylation damage.

4. Repair Mechanisms in the AGT Family

AGT family proteins are small proteins that typically consist of two domains (Figure 1A). Their mechanism of DNA repair is highly conserved and, as mentioned above, involves the irreversible transfer of the alkyl group from the O6 position of guanine or the O4 position of thymine onto a reactive cysteine in the protein. Crystal structures have demonstrated structural conservation between archaeal, bacterial, and eukaryotic AGTs (Figure 1B) [32][44][45][46][47][48][49] and, in particular, of several structural features that are directly linked to the highly conserved repair mechanism. Figure 1A shows these conserved elements, which are usually located in the C-terminal domain of AGTs: a nucleophilic cysteine for alkyl transfer from the damaged base, an active site loop, a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif for DNA binding, an arginine finger that is important for base flipping, and an asparagine hinge. All AGT genes encode an active site pocket that contains a conserved I/V PCHR V/I V/I motif, which harbors the nucleophilic cysteine (C145 in the human protein). Nucleophilic removal of the alkyl group from a guanine (or a thymine) base in the active site pocket is facilitated by interactions from neighboring amino acids (H146 and E172 in human AGT) that deprotonate and thus activate the cysteine in a catalytic triad (Figure 2) [50]. Subsequent transfer of the alkyl group to the cysteine moiety results in a restored guanine moiety and an alkylated AGT, which is then targeted for degradation (see below).

Figure 1. Structural conservation of AGTs. (A) Two-domain structure of human AGT (pdb 1eh6 [48]) with the C-terminal domain shown in blue colors, the N-terminal domain in red, and the connecting loop in grey. Conserved elements in the C-terminal domain are the active site cysteine in stick representation (yellow), the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif (pale purple), including the conserved arginine (R128), and tyrosine (Y114, or phenylalanine in some species) in stick representation, the asparagine hinge that connects the HTH motif and the active site (light blue), and the active site loop (cyan). The Zn2+ ion coordinated by a tetrad of cysteine and histidine residues in the N-terminal domain is shown in green, and the coordinating amino acids in stick representation. (B) Crystal structures of the bacterial E. coli Ada (ecAda, red, C-terminal domain only, pdb 1sfe [32]) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis OGT (mtOGT, pink, pdb 4bhb [44]), as well as archaeal Pyrococcus kodakaraensis AGT (PkOGT, green, pdb 1mgt [45]), and the AlphaFold structural model of archaeal Ferroplasma acidarmanus (FaOGT, cyan, S0ANZ2-F1 AlphaFold Protein Structure Database), are shown overlaid with human AGT in grey.

Figure 2. AGT-DNA interactions. (A) Structure of human AGT bound to an O6-methylguanine in DNA (pdb 1t38 [50]). The DNA is shown in light orange. The O6-methylguanine (stick representation) is shown flipped into the active site pocket of the protein, where it is attacked by the active site cysteine (yellow, replaced by serine in this variant to allow crystallization of a stable complex). The conserved arginine finger (R128) and tyrosine (Y114) that drive and stabilize base flipping are shown in purple in the stick representation. (B) Close-up view of the active site with the water-assisted hydrogen bonding (dotted lines) network between E172, H146, and C145 (yellow) that activates the cysteine nucleophile for de-alkylation of the damaged base (pdb 1eh6 [48]). Red crosses represent water molecules. A schematic of the dealkylation reaction is shown at the bottom (from [50]).

4.1. DNA Interactions and Base Flipping by AGT

AGTs dealkylate DNA bases in single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) as well as double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). AGT binding to dsDNA is mediated by the conserved HTH motif in the C-terminal domain (Figure 1A and Figure 2A). In contrast to the usual HTH interactions, for example, in transcriptional repressors that bind sequence-specifically in the major groove of DNA, the HTH motif of AGTs binds in the minor groove with exclusively non-specific protein-DNA interactions [50], consistent with the observed lack of sequence specificity of AGT-DNA interactions [51]. In the DNA bound state, the highly conserved arginine finger (R128 in human AGT) intercalates into the DNA minor groove to facilitate flipping of the alkylated base out of the DNA double helix and into the active site pocket [50][52]. The arginine residue subsequently fills the space vacated by the flipped-out base [50], stabilizing the extrahelical conformation. Base flipping is further supported through steric interactions by a conserved tyrosine (Y114 in human AGT) [50], which has also been proposed to protect the active site cysteine from oxidation by blocking the binding pocket gate for access of oxidising agents in some species [47].

4.2. The Active Site Pocket

The active site pocket is formed by part of the DNA binding HTH motif, the asparagine hinge that links the active site and DNA binding motif, and part of the active site loop (see Figure 1A). The size of the substrate binding pocket varies between species, depending on the flexibilities of the pocket-lining elements and the presence of bulky amino acid residues (Figure 3). This determines the range of alkyl modifications that can be accommodated and repaired. For human AGT, the affinity and repair activity are stronger for some bulky alkyl lesions compared to small (methyl) modifications on guanine. Thus, repair rates follow the order: benzyl > methyl > ethyl > propyl/butyl [53][54] as a consequence of advantageous hydrophobic interactions, in particular by P140 within the substrate binding pocket (Figure 3A) [53][54]. A conserved lysine (K165) is also essential for O6-benzylguanine, and probably also other bulky O6-alkylguanines, processing by human AGT [55]. In contrast to human AGT, E. coli OGT shows no preference for O6-benzylguanines over O6-methylguanines, likely due to the reduced hydrophobicity of its binding pocket [56]. The alkyltransferase (AGT) activity of the E. coli Ada protein is even completely limited to smaller alkyl groups [49][56][57]. This has been attributed to a bulky amino acid residue (W160) at the upper part of the lesion binding pocket, blocking access for bulkier alkyl groups (Figure 3B) [49][56][57]. Steric interference from bulky amino acid residues in the substrate binding pocket and reduced hydrophobicity of the pocket can cause a complete loss of affinity and repair activity for the bulky benzyl lesions in some species [58]. Other species have evolved highly flexible substrate binding pockets, which likely enables them to accommodate larger alkyl lesions including benzyl [44][59][60](Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Differences in the active site pocket. Detailed view of (A) the active site pocket of human AGT with benzylated cysteine C145 (pdb 1eh8 [48]) and (B) E. coli Ada AGT (pdb 1sfe [32]) in red overlaid with the benzylated human protein in yellow. The benzyl group on C145 in the human protein is shown in yellow both in (A,B). In (B), in the E. coli Ada AGT, tryptophan (W160) would sterically clash with bulky alkyl groups (such as the benzyl) on the cysteine in its active site pocket. Furthermore, the hydrophobic P140 that interacts with the benzyl group in the human variant (A) is replaced by alanine (A140) in the (AGT) alkyltransferase active site of E. coli Ada (B). (C) Flexibility in the active site loop of M. tuberculosis OGT. The black arrow indicates the shift in the loop between the apo form of the protein (bright pink, pdb 4bhb [44]) and the protein bound to a lesion-mimicking chloroethyl analog (N1,O6-ethanoxanthosine) that covalently crosslinks AGT to the DNA [50][59] (pale pink, pdb 4wx9).

4.3. Catabolism of AGT Following Alkylation

The transfer of an alkyl group from a damaged base to the active site cysteine has been shown to destabilize the conformation of the protein (Figure 4A) [48] as well as to disrupt interactions between the C- and N-terminal domains [46][61]. In the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus, destabilization results in a dramatically decreased melting temperature of 20 °C and 35 °C for the methylated and benzylated species, respectively [46]. Consequently, the protein “opens up”, as depicted in Figure 4B, consistent with the finding that alkylation of human AGT renders one of its lysine residues accessible to ubiquitination, which results in proteasomal degradation of AGT [62].

Figure 4. AGT destabilization by alkylation. (A) Accepting the benzyl group from O6-benzylguanine by C145 (yellow) results in the destabilization of a one-turn helix in the active site of human AGT (top: non-alkylated cysteine in a one-turn helix element, pdb 1eh6 [48]; bottom: benzylated cysteine within no secondary protein structure, pdb 1eh8 [48]). (B) In the thermostable archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus, alkylation of the AGT active site cysteine leads to the disruption (black arrow in structure) of interactions between the N-terminal domain (D27 shown in stick representation) and the active site loop (R133, stick representation) that support structural stability at high temperatures. The non-methylated SsOGT is shown in yellow (pdb 4zye), and the methylated form is in orange (pdb 4zyg [46]). This results in an opening of the globular structure of the methylated protein, as indicated schematically in the inset, where the red x indicates the rupture of the D27-R133 interaction (schematic adapted from [46]).

4.4. The N-Terminal Domain

In comparison with the C-terminal domain, which contains the alkyltransferase and DNA binding activities of AGT, the N-terminal domain of AGT is not as conserved (Figure 1B). Available structures of bacterial OGT and Ada and some of the archaeal AGTs (e.g., Pyrococcus kodakaraensis and Ferroplasma acidarmanus) show an additional N-terminal helix in close proximity to the active site (compared to human AGT) [32][44][45][48][49] (S0ANZ2_FERAC AlphaFold database). This additional feature does not sterically restrict the insertion of the alkylated base into the active site pocket and, hence, does not interfere with alkyltransferase activity. However, in some organisms, for example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Sulfolobus solfataricus, it is involved in intra-domain interactions that have been suggested to play a role in the stabilization of the protein [44][46][61] as supported by the large drop in melting temperature upon destabilization of intra-domain interactions by AGT alkylation (as mentioned above) [46]. Crystal structures also revealed the tetrahedral coordination of a Zn2+ ion for human AGT (by C5, C24, H29, and H85) [48], and a disulfide bridge for archaeal AGTs (Sulfolobus solfataricus and Sulfurisphaera tokodaii, between residues C29 and C31) [46][47]. These different intra-domain interactions are believed to stabilize the N-terminal domain fold and, hence, overall protein stability. The N-terminal domain also stabilises interactions with DNA and enhances alkyltransferase activity [44][46][61] possibly by capping the active site pocket that contains the inserted damaged base.

4.5. The Alkyltransferase-like (ATL) Proteins

Some members of the alkyltransferase family do not possess the N-terminal domain. Prominent examples are the alkyltransferase-like (ATL) proteins (Figure 5). ATLs share moderate sequence and high structural similarity with the C-terminal domain of AGTs (~30% sequence similarity between, e.g., human AGT and E. coli ATL [63])). In particular, all structural features for DNA binding and base flipping into the substrate binding pocket (HTH motif with arginine finger and tyrosine) are conserved between AGTs and ATLs (Figure 5A,B) [64][65]. Strikingly, however, these proteins do not possess the active site cysteine that is universal in AGTs: in most ATL proteins, the cysteine is replaced by a tryptophan, for example, in E. coli ATL or S. pombe Atl1 (Figure 5B). As a consequence, E. coli ATL and presumably all other ATL proteins have no in vitro alkyltransferase activity, nor any other catalytic DNA repair activity [63][66], but have been shown to interact with proteins from the NER pathway [64][67] to initiate alkyl lesion repair by NER (see below, section 6).

Figure 5. Alkyltransferase-like proteins. (A) Overlay of human AGT (blue, pdb 1eh6 [48]) and S. pombe ATL (Atl1, pdb 3gva [64], pale pink). Note the complete absence of the N-terminal domain in Atl1. (B) Atl1 bound to O6- benzylguanine in DNA (pdb 3gyh [64]). ATL is shown in cyan, the DNA in pale orange with the lesion base (in stick representation) flipped into the protein’s substrate binding pocket. The amino acids involved in interactions with the alkyl group (W56, P50) and with the flipped-out base (R69) are also shown in stick representation. The conserved arginine (R39) and tyrosine (Y25) that mediate base flipping by direct interactions with the DNA are shown in purple-blue. DNA contacts by the C-terminal extension loop and extended N-terminal helix enhance DNA bending. (C) An overlay of the unbound form of Atl1 from S. pombe (pale pink, pdb 3gva [64]) and the lesion-bound form (cyan, pdb 3gyh [64]) demonstrate the large shift of the active site loop (arrow) towards the binding pocket that allows R69 to interact with the damaged base. W56 (in place of the active site cysteine in AGT) and P50 of the binding pocket, as well as R69 on the active site loop, are shown in stick representation. The bound DNA and flipped-out alkylated base have been removed for clarity. Below, are surface representations of unbound and lesion-bound Atl1 to visualize the open-to-close conformational change in the protein upon lesion binding, which results in stable alkyl lesion binding by ATL with KD’s in the low nanomolar to sub-nanomolar range [64][66][68][69].

5. The DNA Alkyltransferase Protein Family–Distribution in Nature

AGTs and their ATL homologs are highly conserved in nature, being found in all kingdoms of life, from bacteria to archaea and eukaryotes [63][64][65][64][66][70][71] (Figure 6). Some organisms possess only an AGT, for example, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and H. sapiens; others only an ATL, for example, the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe [66][72][73]. In some organisms such as E. coli [63][74], both AGT and ATL are present. Indeed, E. coli (and related prokaryotes) contains two different genes, Ogt and Ada that code for proteins with alkyltransferase activity. The Ada protein itself consists of two alkyltransferase domains, one acting on O6-alkylguanines and the other on MPTs, while in some other organisms, such as Aspergillus, the AGT and MPT functions are on separate proteins. Some organisms have also evolved fusion proteins of AGT with other enzymatic functions such as the AGTendoV fusion in Ferroplasma acidarmanus, which possesses AGT alkyltransferase activity as well as an endonuclease activity for the repair of other DNA alkylation products that are usually targeted by the BER pathway [75].

Figure 6. Distribution of the DNA alkyltransferase superfamily. (A) This overview shows currently identified species and is based on [40][41][42][44][45][47][60][61][63][64][65][69][70][71][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89]. The pdb identifier for structural data is given in brackets where available. * indicates that alkyltransferase activity is only implied by sequence and has not been shown experimentally. (B) Exemplary multiple sequence alignment (using EMBL-EBI Clustal Omega) for the AGT/ATL protein variants from E. coli, OGT, Ada, and ATL, the human, yeast (S. cerevisiae), and C. Rheinhardtii AGT proteins, as well as the archaeal AGTEndoV fusion protein from F. acidarmanus. * indicates fully conserved residue, : indicates conservation of strongly similar properties of a residue. Different AGTs possess sequence identities of ~30–50% and similarities of ~40–70% (protein blast, NCBI). ATLs from different species have typical sequence identities of around 50% (e.g., Vibrio parahaemolyticus versus E. coli). Even between AGTs and ATLs, sequence conservation is high (e.g., 34% identity for E. coli ATL and human AGT). Highlighted are the highly conserved regions and residues: the consensus motif PCHRV/IV/I for AGT with C replaced by W in ATL in yellow; in pink the conserved tyrosine that supports base flipping; in cyan, the conserved arginine finger; in green the glutamate (or aspartate in AGTEndoV) that activates cysteine for alkyl group transfer as part of a catalytic triad together with histidine in the consensus motif (see section 4). The HTH motif for DNA binding is boxed.

6. Functional Implications of Protein Interactions

Both AGT and ATL have been shown to form cooperative clusters on DNA at high protein concentrations (>4 μM; Figure 7 and Figure 8A,B) [51][67][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][51, 67, 90-97], while in the absence of DNA, they are predominantly monomeric [51][67][91][95][98][51, 67, 91, 95, 98] (Figure 7). It is worth noting that such cooperative clusters have yet to be demonstrated in a cellular context. Nevertheless, these data shed light on the probable lesion search and processing strategies of AGT and ATL, as outlined in the following sections. In addition to cooperative interactions between individual AGT or ATL monomers on DNA, both have been shown to interact with various other protein systems, and their role in repairing a large spectrum of different types of O6-alkylguanines and O4-alkylthymines has been investigated.

Figure 7. AGT is monomeric in the absence of DNA. Sedimentation velocity AUC shows predominantly monomeric AGT at high protein concentration in the absence of DNA ((left): 17 μM [95][98][95, 98]) as well as on DNA at low micromolar concentration (4 μM, (right)), and oligomers of AGT on DNA at high protein concentration (17 μM, (right)) [95].

6.1. Cooperative DNA Binding in DNA Lesion Search

In AGT, the protein-protein interactions for cooperative cluster formation, which are predominantly of an electrostatic nature, are located in the N-terminal domain (see model in Figure 8C) [90][91][90, 91]. The model of the DNA-bound AGT clusters shows protein-protein interactions between each monomer with its third removed neighbor (e.g., AGT#1 interacts with AGT#4, AGT#2 interacts with AGT#5, etc. in the cluster via residues in their N-terminal domains). In the case of ATL proteins, which lack the N-terminal domain of AGT, interactions for cluster formation on DNA have been modeled to reside in completely different sites, i.e., in the very N-terminal helix and the C-terminal extension loop that is not present in AGTs (Figure 8D) [67]. The relatively small interaction interface in the crude structural model suggests that cooperative interactions in ATL clusters are much weaker than those for AGT [67].

Both AGT and ATL clusters on DNA have been shown to be limited in their lengths [51][67][95][51, 67, 95], with approximately four monomers per cluster suggested for ATL versus approximately seven monomers per cluster for AGT (from EMSAs and AUC studies using DNA of different lengths, as well as cluster lengths in AFM analyses) [50][51][64][67][95][50, 51, 64, 67, 95]. These maximum lengths may be restricted by the energetic cost from the bending strain induced in the DNA by each added monomer in the cluster, which eventually cancels out the energy gained from the cooperative protein-protein interactions [51].

Figure 8. Cluster formation on DNA. (A) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of AGT clusters on undamaged DNA [51][99][51, 99]. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of AGT (top) and ATL (bottom) [67][96][67, 96]. Black and red arrows indicate clusters and lesion-specific complexes, respectively. Higher affinity for O6-methylguanine leads to the initial binding of monomeric AGT/ATL at the lesion, followed by cluster formation at higher protein concentrations (0–5.1 μM and 0–2 μM for AGT and ATL, respectively, with corresponding DNA concentrations of 150 nM and 50 nM). Note the one-step formation of clusters for the undamaged substrate indicative of cooperativity (shown only for ATL). (C,D) Models of AGT (C) and ATL (D) clusters on DNA [67][90][67, 90]. AGT clusters are stabilized by protein-protein interactions between each monomer and its third removed neighbor (e.g., between blue and pink molecules at the top, as indicated by the oval). In ATL clusters, an N-terminal helix and the C-terminus extension loop form a weak interaction interface (as indicated by the oval). Figures in panel (B) have originally been published in Nucleic Acids Research and PNAS (modified from original), copyright at Oxford University Press and the National Academy of Sciences, respectively.

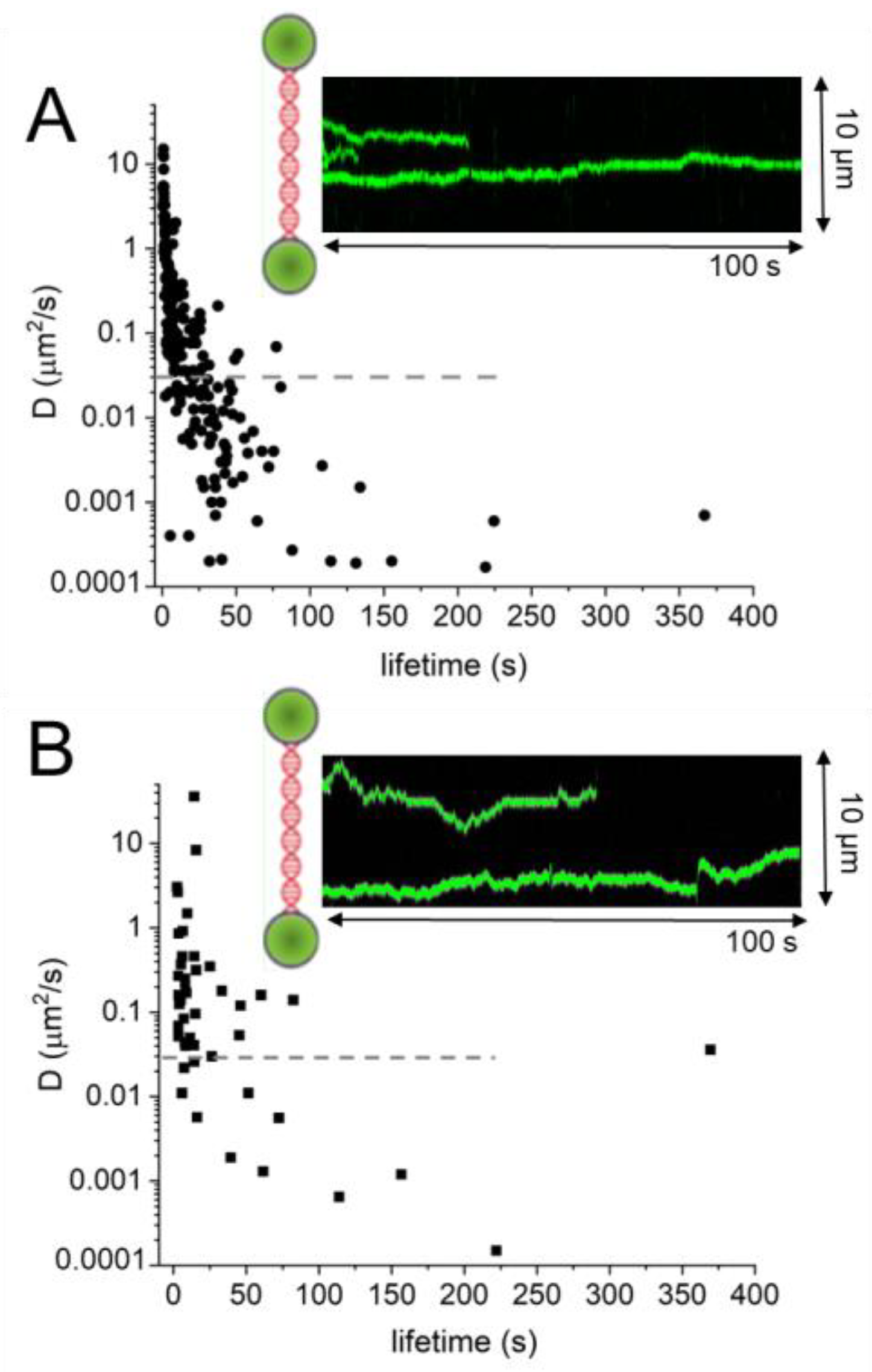

Preferential repair by AGT of O6-methylguanines towards the 3′ compared to the 5′ end of a short ssDNA substrate has suggested 5′-to-3′ directionality of AGT on DNA [50]. It has been speculated that cooperative clusters may play a role in enhancing the speed and efficiency of target site localization by preferential addition of monomer subunits at their 5′ ends and preferential dissociation from their 3′ ends [50][51][50, 51]. However, recent studies using single-molecule fluorescence microscopy coupled with a dual trap optical tweezers system have demonstrated no enhancement of DNA translocation for AGT clusters versus monomers [95]. Furthermore, no directionality of AGT movement on DNA (either as monomers or clusters and on dsDNA as well as ssDNA) has been observed in these single molecule visualizations of AGT cluster movement on DNA [95]. In fact, both AGT and ATL clusters moved without any directional bias on DNA (Figure 9) [67][95][67, 95]. A possible explanation for the apparent contrast between results from the AGT lesion repair assay and the single molecule fluorescence experiments, may be the different distance regimes probed (70 nucleotide long ssDNA, probing distances < ~20 nm in repair assays versus ≥ ca. 100 nm pixel resolution in single molecule fluorescence experiments, and a potential directionality in cluster growth versus non-directional DNA scanning by AGT clusters.

Using optical tweezers-coupled single molecule fluorescence data, DNA lesion search dynamics on DNA by AGT and ATL have been quantified by mean square displacement (MSD) analyses (Figure 9) [67][95][67, 95]. Diffusion constants of long-lived complexes on DNA were predominantly lower than the theoretical limit for rotational movement along the DNA double helix, and are thus consistent with AGT and ATL clusters scanning the DNA by rotational sliding along the DNA minor groove (to which the proteins bind, see e.g. Figure 2).

Figure 9. DNA lesion search dynamics. One-dimensional diffusion constants (D) on DNA plotted over the lifetimes of complexes on the DNA for (A) AGT [95] and (B) ATL [67]. The insets show representative kymographs (green traces) obtained by fluorescence microscopy-coupled dual trap optical tweezers, in which the y direction corresponds to the positions on the DNA tether (shown schematically between two beads held in the two optical traps), and the x direction to time. Mean square displacement analyses gave higher D values for ATL than for AGT: average values of 1.3 μm2/s for ATL versus 0.7 μm2/s for AGT. For AGT, higher diffusion constants predominantly stem from short-lived complexes (with lifetimes on the DNA of <10 s). The horizontal dashed lines in the D over lifetime plots indicate the theoretical limit for rotational diffusion of (quantum dot labelled) AGT and ATL along the DNA double helix. While these data were obtained at different protein concentrations (for ATL: 2 μM; for AGT: 4 μM) and in different buffers (for ATL: 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 25 mM Na-acetate, 10 mM Mg-acetate; for AGT: 10 mM Tris pH 7.7, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT), measurements with 4 μM ATL in the AGT experimental buffer gave comparable results as for the ATL buffer above (average D value of 1.5 μm2/s).

6.2. Cooperative DNA Binding in DNA Lesion Processing

While AGT clusters also form on undamaged DNA (see previous section), recent single-molecule fluorescence optical tweezers studies demonstrated preferential formation and/or stabilization of AGT clusters at an O6-methylguanine in DNA [95]. This is in contrast to the monomeric lesion-bound AGT complexes seen in crystal structures (e.g., Figure 3A) but is consistent with previous biochemical studies that also proposed a role of cooperative complex formation by AGT in lesion binding [96]. Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments showed a clear dependence of the oligomeric state of DNA-bound AGT on the protein:DNA ratio [95]; and while in crystallographic studies, the [protein]:[DNA] ratio is 1:1, single molecule fluorescence microscopy or biochemical assays typically employ [protein]>>[DNA].

6.3. AGT Interactions with DNA Replication

Although AGT does not require any other protein factors for alkyl lesion repair, several interactions with proteins from other DNA repair and DNA processing pathways have been identified. Proteins in cancer cell extracts that were co-immunoprecipitated with AGT included the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) clamp that serves as a platform for replication proteins on DNA and the MCM2 (minichromosome maintenance complex 2) component of the replicative helicase as well as the ORC1 origin recognition complex [100]. It should be noted, however, that these co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed in the presence of DNA, so apparent interactions between proteins may in fact be due to mutual DNA binding. Direct physical contacts between AGT and DNA replication proteins hence remain to be demonstrated. Larger alkylguanines such as O6-pyridyloxobutylguanine (pobG) or O6-benzylguanine have been shown to present replication blocks [101], which can be overcome by specific translesion synthesis polymerases [102].

6.4. AGT Interactions with DNA Mismatch Repair Proteins

G:T mispairs, which arise from the misincorporation of thymine opposite O6-alkylguanine during DNA replication, are targets of the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) pathway. As mentioned above, in the absence of alkyl lesion repair by AGT, futile rounds of MMR due to persisting alkylG:T mispairing in DNA replication eventually cause cell death [103]. Proteomic analyses have identified a potential interaction of AGT with MSH2 [100], which, together with MSH3 or MSH6, recognizes base-base or insertion-deletion mismatches in DNA to initiate the MMR pathway. However, as above (section 6.3), these experiments were performed in the presence of DNA, so direct physical interactions between MSH2 and AGT remain to be confirmed.

6.5. Roles of AGT in Transcription Regulation

Like the E. coli Ada protein [39], hAGT can also modulate transcription, although not of its own gene: upon alkylation, hAGT has been shown to directly interact with the estrogen receptor (ER) transcription factor [104]. This blocks ER activation by its coactivator and represses the production of cell growth-enhancing factors and cell proliferation [104]. DNA alkylation is thus translated by hAGT into a signal for cell cycle arrest, allowing more time for the synthesis of more AGT and, hence, to repair toxic (and mutagenic) alkyl lesions before the next round of replication. hAGT has also been shown to interact with the CPB/p300 histone acetylase [104], which modifies histones to open chromatin, allowing transcription but also making the DNA more vulnerable to alkylation (and other) damaging agents.

6.6. AGT and ATL Interactions with NER

ATLs have been shown to directly interact with NER proteins [64][67][64, 67]. In addition to an epistatic relationship with the eukaryotic NER endonuclease XPG homolog in S. pombe (by S. pombe Atl1), direct interactions with the prokaryotic NER initiating enzyme UvrA and the NER UvrC endonuclease have been demonstrated (for S. pombe Atl1 and E. coli ATL) [64][67][64, 67], supporting the direct recruitment of the NER system by ATL. Stronger binding affinity to larger alkyl lesions (e.g., O6-oxobutylguanine, pobG) lesions versus smaller lesions (e.g., O6-methylguanine) by ATL [64][68][64, 68] (see also Figure 5C) may play an important role in pathway selection for alkyl lesion repair. Weaker binding affinities for smaller alkyl lesions may, following recruitment, allow the NER proteins to displace ATL from the lesion for repair by the global genome repair sub-pathway of NER (GG-NER), while larger alkyl lesions that have stronger binding affinities for ATL may lead to persistent ATL complexes on the DNA, which could stall RNA polymerase transcription and activate the transcription-coupled NER sub-pathway (TC-NER) [68]. Clonogenic assays indeed demonstrated the involvement of the GG-NER sub-pathway in the ATL-associated repair of small alkyl lesions [68]. In contrast, cells containing bulkier alkyl lesions were more sensitive to the deletion of TC-NER-specific genes [68].

Co-localization of AGT with sites of active transcription [58][104][105][58, 104, 105] also hints at a potential role of AGT in the TC-NER pathway similar to that proposed for ATL on large alkyl lesions in DNA. Previous studies also implicated the NER pathway in the repair of O6-ethylguanine, O6-chloroethylguanine, and large branched-chain O6-alkylguanines [102][106][107][108][102, 106-108], although the role of AGT in NER of these lesions remains to be established.

6.7. Posttranslational Modifications of AGT

AGT has also recently been shown to directly interact with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) with high, nanomolar affinity [109]. PARP1 functions in BER as well as other DNA repair pathways by adding poly-ADP-ribose chains (PAR) to its protein targets, as well as itself. These PAR chains can bind to several DNA repair proteins, leading to their enhanced recruitment to specific PARP1-marked DNA lesions [110][111][112]. For example, PARylation has been shown to be involved in the recruitment of the BER endonuclease APE1, the structure factor XRCC1 that plays a role in the organization of the BER mechanism, as well as other enzymes [112][113][114]. PARylation of AGT has been shown to enhance AGT activity in alkyl lesion repair [109].

In addition to PARylation, AGT has been shown to be posttranslationally modified by phosphorylation, which inhibits AGT repair activity [115][116][117].

7. AGT in Cancer Chemotherapy

Methylating agents (dacarbazine, temozolomide (TMZ), procarbazine, and streptozotocin) and chloroethylating agents (e.g., 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-N-nitrosourea (BCNU)), among others, are used as cytotoxics in the treatment of various types of human cancers [118]. These drugs are also referred to collectively as O6-alkylating agents, and there is ample evidence that AGT provides protection against the toxic effects of these agents in cultured cells [119][120][121]. AGT expression levels and activities vary greatly in different human tumor types and also normal tissues [70][122][123][124][70, 122-124], and it seems reasonable to suggest that this may be the basis of the successful use of O6-alkylating agents only in certain tumor types.

The possibility that inhibition of AGT activity might be a strategy for enhancing the chemotherapeutic effectiveness in tumors treated with O6-alkylating agents has led to the synthesis and testing of a substantial number of candidate drugs. These “pseudosubstrates” are predominantly free-base guanines modified at the O6-position with a wide range of alkyl groups [125], although other compounds are also effective AGT inactivators [126]. Alkyl group transfer to the active pocket cysteine prevents the repair of O6-alkylguanine in DNA and, at least for O6-benzylguanine, results in AGT ubiquitination and degradation in the proteasome (see above) [62][127][62, 127].

Human tumor xenografts grown in immune-deficient mice have been used to demonstrate the ability of these agents, principally O6-benzylguanine but also other alkyl guanine modifications, to enhance tumor growth inhibition by alkylating agents such as TMZ, and promising preclinical responses were obtained [128][129][130]. However, none of the clinical trials of combination therapies (of AGT inhibitors and alkylating agents) have, so far, shown sufficient patient benefit. Potential improvements may be expected from AGT inactivators that specifically target tumor cells [131][132][133] or attenuating AGT activity by tumor treating fields [134], alkylating drug combinations [135], or antisense strategies [136] in future studies. Another strategy that has been explored is myeloprotective ex vivo gene therapy using inactivator-resistant mutant AGTs cloned into retrovirus or lentivirus vectors in attempts to reduce dose-limiting bone marrow toxicity concomitantly with tumor sensitisation [137][138][139][140]. Indeed, given that some O6-alkylating agents are front-line therapies, any strategies that might improve the outcome for cancer patients is worth pursuing.

References

- Fahrer, J. and Christmann, M. DNA Alkylation Damage by Nitrosamines and Relevant DNA Repair Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4684. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054684.

- Abdelhady, R.; Senthong, P.; Eyers, C.E.; Reamtong, O.; Cowley, E.; Cannizzaro, L.; Stimpson, J.; Cain, K.; Wilkinson, O.J.; Williams, N.H.; Povey, A.C. Mass Spectrometric Analysis of the Active Site Tryptic Peptide of Recombinant O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase Following Incubation with Human Colorectal DNA Reveals the Presence of an O6-Alkylguanine Adductome. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2023, 36, 1921–1929. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.3c00207.

- Singer, B. DNA damage: Chemistry, repair, and mutagenic potential. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1996, 23, 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1006/rtph.1996.0002.

- Fu, D.; Calvo, J.A.; Samson, L.D. Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 104–120. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3185.

- Wyatt, M.D. and Pittman, D.L. Methylating agents and DNA repair responses: Methylated bases and sources of strand breaks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 1580–1594. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx060164e.

- Beranek, D.T. Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutat. Res. 1990, 231, 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0027-5107(90)90173-2.

- Yarosh, D.B. The role of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in cell survival, mutagenesis and carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 1985, 145, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8817(85)90034-3.

- Mackay, W.J.; Han, S.; Samson, L.D. DNA alkylation repair limits spontaneous base substitution mutations in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 3224–3230. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.176.11.3224-3230.1994.

- Warren, J.J.; Forsberg, L.J.; Beese, L.S. The structural basis for the mutagenicity of O6-methyl-guanine lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19701–19706. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0609580103.

- Kaina, B; Ziouta, A.; Ochs, K.; Coquerelle, T. Chromosomal instability, reproductive cell death and apoptosis induced by O6-methylguanine in Mex-, Mex+ and methylation-tolerant mismatch repair compromised cells: Facts and models. Mutat. Res. 1997, 381, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00187-5.

- Fink, D.; Aebi, S.; Howell, S.B. The role of DNA mismatch repair in drug resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998, 4(1), 1-6.

- Kanzawa, T.; Germano, I.M.; Komata, T.; Ito, H.; Kondo, Y.; Kondo, S. Role of autophagy in temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity for malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11, 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359.

- Gilman, A. The initial clinical trial of nitrogen mustard. Am. J. Surg. 1963, 105, 574-578. http://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(63)90232-0.

- Singh, R.K.; Kumar, S.; Prasad, D.N.; Bhardwaj, T.R. Therapeutic journery of nitrogen mustard as alkylating anticancer agents: Historic to future perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 151, 401-433. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.04.001.

- Chanutin, A. and Gjessing, E.C. The effect of nitrogen mustards upon the ultraviolet absorption spectrum of thymonucleate, uracil and purines. Cancer Res. 1946, 6(11), 599-601.

- Elmore, D.T.; Gulland, J.M.; Jordan, D.O.; Taylor, H.F. The reaction of nucleic acids with mustard gas. Biochem J. 1948, 42(2), 308-16.

- Brookes, P. and Lawley, P.D. The reaction of mustard gas with nucleic acids in vitro and in vivo. Biochem J. 1960, 77(3), 478-84. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj0770478.

- Craddock, V.M. and P.N. Magee, P.N. Methylation of Liver DNA in the Intact Animal by the Carcinogen Dimethylnitrosamine during Carcinogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1965, 95, 677-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2787(65)90526-5.

- Craddock, V.M. and Magee, P.N. Analysis of bases of rat-liver nucleic acids after administration of the carcinogen dimethylnitrosamine. Biochem J. 1966, 100(3), 724-32. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj1000724.

- Lawley, P.D.; Brookes, P.; Magee, P.N.; Craddock, V.M.; Swann, P.F. Methylated bases in liver acids from rats treated with dimethylnitrosamine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1968, 157(3), 646-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2787(68)90167-6.

- Swann, P.F. and Magee, P.N. Nitrosamine-induced carcinogenesis. The alklylation of nucleic acids of the rat by N-methyl-N-nitrosourea, dimethylnitrosamine, dimethyl sulphate and methyl methanesulphonate. Biochem J. 1968, 110(1), 39-47. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj1100039.

- Lawley, P.D. Methylation of DNA by N-methyl-N-nitrosourethane and N-methyl-N-nitroso-N'-nitroguanidine. Nature 1968, 218(5141), 580-581. http://doi.org/10.1038/218580a0.

- Schoental, R. Methylation of nucleic acids by N[14C]-methyl-N-nitrosourethane in vitro and in vivo. Biochem J. 1967, 102(1), 5C-7C. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj1020005c.

- Verly, W.G. and Brakier, L. The letal action of monofunctional and bifunctional alkylating agents on T7 coliphage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1969, 174(2), 674-85. http://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2787(69)90296-2.

- Lawley, P.D. and Brookes, P. Further Studies on the Alkylation of Nucleic Acids and Their Constituent Nucleotides. Biochem J. 1963, 89(1), 127-38. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj0890127.

- Lawley, P.D. and Brookes, P. Methylation of adenine in deoxyadenylic acid or deoxyribonucleic acid at N-7. Biochem J. 1964, 92(3), 19C-20C. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj0920019c.

- Loveless, A. Possible relevance of O-6 alkylation of deoxyguanosine to the mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of nitrosamines and nitrosamides. Nature 1969, 223(5202), 206-207. http://doi.org/10.1038/223206a0.

- Lawley, P.D.; Orr, D.J.; Shah, S.A.; Farmer, P.B.; Jarman, M. Reaction products from N-methyl-N-nitrosourea and deoxyribonucleic acid containing thymidine residues. Synthesis and identification of a new methylation product, O4-methyl-thymidine. Biochem J. 1973, 135, 193–201. http://doi.org/10.1042/bj13350193.

- Loveless, A.; Cook, J.; Wheatley, P. Recovery from the 'Lethal' Effects of Cross-Linking Alkylation. Nature 1965, 205, 980-983. http://doi.org/10.1038/205980a0.

- Samson, L. and Cairns, J. New Pathway for DNA-Repair in Escherichia coli. Nature 1977, 267, 281–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/267281a0.

- Jeggo, P.; Defais, M.; Samson, L.; Schendel, P. Adaptive Response of Escherichia coli to Low-Levels of Alkylating Agent—Comparison with Previously Characterized DNA-Repair Pathways. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1977, 157, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/Bf00268680.

- Moore, M.H.; Gulbis, J.M.; Dodson, E.J.; Demple, B.; Moody, P.C. Crystal structure of a suicidal DNA repair protein: The Ada O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase from E. coli. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 1495–1501. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06410.x.

- Potter, P.M.; Wilkinson, M.C.; Fitton, J.; Carr, F.J.; Brennand, J.; Cooper, D.P.; Margison, G.P. Characterization and Nucleotide-Sequence of Ogt, the O6-Alkylguanine-DNA-Alkyltransferase Gene of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987, 15, 9177–9193. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/15.22.9177.

- Potter, P.M.; Kleibl, K.; Cawkwell, L.; Margison, G.P. Expression of the Ogt Gene in Wild-Type and Ada Mutants of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 8047–8060. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/17.20.8047.

- He, C.; Hus, J.C.; Sun, L.J.; Zhou, P.; Norman, D.P.; Dotsch, V.; Wei, H.; Gross, J.D.; Lane, W.S.; Wagner, G.; et al. A methylation-dependent electrostatic switch controls DNA repair and transcriptional activation by E. coli ada. Mol. Cell 2005, 20, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.013.

- Nakabeppu, Y. and Sekiguchi, M. Regulatory mechanisms for induction of synthesis of repair enzymes in response to alkylating agents: Ada protein acts as a transcriptional regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 6297–6301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.17.6297.

- Takinowaki, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ohkubo, T. 1H, 13C and 15N resonance assignments of the N-terminal 16 kDa domain of Escherichia coli Ada protein. J. Biomol. NMR 2004, 29, 447–448. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JNMR.0000032549.04619.87.

- Teo, I.; Sedgwick, B.; Demple, B.; Li, B.; Lindahl, T. Induction of resistance to alkylating agents in E. coli: The ada+ gene product serves both as a regulatory protein and as an enzyme for repair of mutagenic damage. EMBO J. 1984, 3, 2151–2157. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02105.x.

- Sedgwick, B.; Robins, P.; Totty, N.; Lindahl, T. Functional domains and methyl acceptor sites of the Escherichia coli ada protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 4430–4433.

- Baker, S.M.; Margison, G.P.; Strike, P. Inducible alkyltransferase DNA repair proteins in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20, 645–651. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/20.4.645.

- O’Hanlon, K.A.; Margison, G.P.; Hatch, A.; Fitzpatrick, D.A.; Owens, R.A.; Doyle, S.; Jones, G.W. Molecular characterization of an adaptive response to alkylating agents in the opportunistic pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 7806–7820. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks522.

- Morohoshi, F.; Hayashi, K.; Munakata, N. Bacillus subtilis ada operon encodes two DNA alkyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 5473–5480. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/18.18.5473.

- Baranczewski, P.; Nehls, P.; Rieger, R.; Rajewsky, M.F.; Schubert, I. Removal of O6-methylguanine from plant DNA in vivo is accelerated under conditions of clastogenic adaptation. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1997, 29, 400–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(1997)29:4<400::aid-em9>3.0.co;2-d.

- Miggiano, R.; Casazza, V.; Garavaglia, S.; Ciaramella, M.; Perugino, G.; Rizzi, M.; Rossi, F. Biochemical and structural studies of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis O6-methylguanine methyltransferase and mutated variants. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 2728–2736. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.02298-12.

- Hashimoto, H.; Inoue, T.; Nishioka, M.; Fujiwara, S.; Tagaki, M.; Imanaka, T.; Kai, Y. Hyperthermostable protein structure maintained by intra and inter-helix ion-pairs in archaeal O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 292, 707–716. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1999.3100.

- Perugino, G.; Miggiano, R.; Serpe, M.; Vettone, A.; Valenti, A.; Lahiri, S.; Rossi, F.; Rossi, M.; Rizzi, M.; Ciaramella, M. Structure-function relationships governing activity and stability of a DNA alkylation damage repair thermostable protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 8801–8816. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv774.

- Kikuchi, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Iizuka, Y.; Tsunoda, M. Roles of the hydroxy group of tyrosine in crystal structures of Sulfurisphaera tokodaii O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2021, 77, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053230X21011055.

- Daniels, D.S.; Mol, C.D.; Arvai, A.S.; Kanugula, S.; Pegg, A.E.; Tainer, J.A. Active and alkylated human AGT structures: A novel zinc site, inhibitor and extrahelical base binding. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1719–1730. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/19.7.1719.

- Wibley, J.E.; Pegg, A.E.; Moody, P.C. Crystal structure of the human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.2.393.

- Daniels, D.S.; Woo, T.T.; Luu, K.X.; Noll, D.M.; Clarke, N.D.; Pegg, A.E.; Tainer, J.A. DNA binding and nucleotide flipping by the human DNA repair protein AGT. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 11, 714–720. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb791.

- essmer, I.; Melikishvili, M.; Fried, M.G. Cooperative cluster formation, DNA bending and base-flipping by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 8296–8308. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks574.

- Hu, J.; Ma, A.; Dinner, A.R. A two-step nucleotide-flipping mechanism enables kinetic discrimination of DNA lesions by AGT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4615–4620. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708058105.

- Mijal, R.S.; Thomson, N.M.; Fleischer, N.L.; Pauly, G.T.; Moschel, R.C.; Kanugula, S.; Fang, Q.; Pegg, A.E.; Peterson, L.A. The repair of the tobacco specific nitrosamine derived adduct O6-[4-Oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase variants. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004, 17, 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx0342417.

- Coulter, R.; Blandino, M.; Tomlinson, J.M.; Pauly, G.T.; Krajewska, M.; Moschel, R.C.; Peterson, L.A.; Pegg, A.E.; Spratt, T.E. Differences in the rate of repair of O6-alkylguanines in different sequence contexts by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 1966–1971. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx700271j.

- Xu-Welliver, M.; Kanugula, S.; Loktionova, N.A.; Crone, T.M.; Pegg, A.E. Conserved residue lysine165 is essential for the ability of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase to react with O6-benzylguanine. Biochem. J. 2000, 347, 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1042/0264-6021:3470527.

- Goodtzova, K.; Kanugula, S.; Edara, S.; Pauly, G.T.; Moschel, R.C.; Pegg, A.E. Repair of O6-benzylguanine by the Escherichia coli Ada and Ogt and the human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 8332–8339. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.13.8332.

- Crone, T.M.; Kanugula, S.; Pegg, A.E. Mutations in the Ada O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase conferring sensitivity to inactivation by O6-benzylguanine and 2,4-diamino-6-benzyloxy-5-nitrosopyrimidine. Carcinogenesis 1995, 16, 1687–1692. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/16.8.1687.

- Pegg, A.E.; Boosalis, M.; Samson, L.; Moschel, R.C.; Byers, T.L.; Swenn, K.; Dolan, M.E. Mechanism of inactivation of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase by O6-benzylguanine. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 11998–12006. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00096a009.

- Miggiano, R.; Perugino, G.; Ciaramella, M.; Serpe, M.; Rejman, D.; Pav, O.; Pohl, R.; Garavaglia, S.; Lahiri, S.; Rizzi, M. Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase protein clusters assembled on to damaged DNA. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20150833.

- Roberts, A.; Pelton, J.G.; Wemmer, D.E. Structural studies of MJ1529, an O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2006, 44, S71–S82. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.1823.

- Morrone, C.; Miggiano, R.; Serpe, M.; Massarotti, A.; Valenti, A.; Del Monaco, G.; Rossi, M.; Rossi, F.; Rizzi, M.; Perugino, G.; et al. Interdomain interactions rearrangements control the reaction steps of a thermostable DNA alkyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.10.020.

- Xu-Welliver, M. and Pegg, A.E. Degradation of the alkylated form of the DNA repair protein, O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 823–830. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/23.5.823.

- Pearson, S.J.; Ferguson, J.; Santibanez-Koref, M.; Margison, G.P. Inhibition of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by an alkyltransferase-like protein from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 3837–3844. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki696.

- Tubbs, J.L.; Latypov, V.; Kanugula, S.; Butt, A.; Melikishvili, M.; Kraehenbuehl, R.; Fleck, O.; Marriott, A.; Watson, A.J.; Verbeek, B.; et al. Flipping of alkylated DNA damage bridges base and nucleotide excision repair. Nature 2009, 459, 808–813. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08076.

- Aramini, J.M.; Tubbs, J.L.; Kanugula, S.; Rossi, P.; Ertekin, A.; Maglaqui, M.; Hamilton, K.; Ciccosanti, C.T.; Jiang, M.; Xiao, R.; et al. Structural basis of O6-alkylguanine recognition by a bacterial alkyltransferase-like DNA repair protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13736–13741. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.093591.

- Pearson, S.J.; Wharton, S.; Watson, A.J.; Begum, G.; Butt, A.; Glynn, N.; Williams, D.M.; Shibata, T.; Santibanez-Koref, M.F.; Margison, G.P. A novel DNA damage recognition protein in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 2347–2354. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl270.

- Rill, N.; Mukhortava, A.; Lorenz, S.; Tessmer, I. Alkyltransferase-like protein clusters scan DNA rapidly over long distances and recruit NER to alkyl-DNA lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9318–9328. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916860117.

- Latypov, V.F.; Tubbs, J.L.; Watson, A.J.; Marriott, A.S.; McGown, G.; Thorncroft, M.; Wilkinson, O.J.; Senthong, P.; Butt, A.; Arvai, A.S.; et al. Atl1 regulates choice between global genome and transcription-coupled repair of O6-alkylguanines. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.028.

- Wilkinson, O.J.; Latypov, V.; Tubbs, J.L.; Millington, C.L.; Morita, R.; Blackburn, H.; Marriott, A.; McGown, G.; Thorncroft, M.; Watson, A.J.; et al. Alkyltransferase-like protein (Atl1) distinguishes alkylated guanines for DNA repair using cation-pi interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18755–18760. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1209451109.

- Margison, G.P.; Povey, A.C.; Kaina, B.; Santibanez Koref, M.F. Variability and regulation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Carcinogenesis 2003, 24, 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgg005.

- Perugino, G.; Vettone, A.; Illiano, G.; Valenti, A.; Ferrara, M.C.; Rossi, M.; Ciaramella, M. Activity and regulation of archaeal DNA alkyltransferase: Conserved protein involved in repair of DNA alkylation damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 4222–4231. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.308320.

- Margison, G.P.; Butt, A.; Pearson, S.J.; Wharton, S.; Watson, A.J.; Marriott, A.; Caetano, C.M.; Hollins, J.J.; Rukazenkova, N.; Begum, G.; et al. Alkyltransferase-like proteins. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 1222–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.014.

- Morita, R.; Nakagawa, N.; Kuramitsu, S.; Masui, R. An O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase-like protein from Thermus thermophilus interacts with a nucleotide excision repair protein. J. Biochem. 2008, 144, 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvn065.

- Mazon, G.; Philippin, G.; Cadet, J.; Gasparutto, D.; Fuchs, R.P. The alkyltransferase-like ybaZ gene product enhances nucleotide excision repair of O6-alkylguanine adducts in E. coli. DNA Repair 2009, 8, 697–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.022.

- Kanugula, S.; Pauly, G.T.; Moschel, R.C.; Pegg, A.E. A bifunctional DNA repair protein from Ferroplasma acidarmanus exhibits O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and endonuclease V activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 3617–3622. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408719102.

- Kanugula, S. and Pegg, A.E. Novel DNA repair alkyltransferase from Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2001, 38, 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/em.1077.

- Elkins, J.G.; Podar, M.; Graham, D.E.; Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.; Randau, L.; Hedlund, B.P.; Brochier-Armanet, C.; Kunin, V.; Anderson, I.; et al. A korarchaeal genome reveals insights into the evolution of the Archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 8102–8107. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801980105.

- Waters, E.; Hohn, M.J.; Ahel, I.; Graham, D.E.; Adams, M.D.; Barnstead, M.; Beeson, K.Y.; Bibbs, L.; Bolanos, R.; Keller, M.; et al. The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans: Insights into early archaeal evolution and derived parasitism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12984–12988. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1735403100.

- Putnam, N.H.; Srivastava, M.; Hellsten, U.; Dirks, B.; Chapman, J.; Salamov, A.; Terry, A.; Shapiro, H.; Lindquist, E.; Kapitonov, V.V.; et al. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization. Science 2007, 317, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1139158.

- Kanugula, S. and Pegg, A.E. Alkylation damage repair protein O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase from the hyperthermophiles Aquifex aeolicus and Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Biochem. J. 2003, 375, 449–455. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20030809.

- Kooistra, R.; Zonneveld, J.B.; Watson, A.J.; Margison, G.P.; Lohman, P.H.; Pastink, A. Identification and characterisation of the Drosophila melanogaster O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 1795–1801. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.8.1795.

- Skorvaga, M.; Raven, N.D.; Margison, G.P. Thermostable archaeal O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6711–6715. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.12.6711.

- Tang, L.; Guerard, M.; Zeller, A. Quantitative assessment of the dose-response of alkylating agents in DNA repair proficient and deficient ames tester strains. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2014, 55, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/em.21825.

- Onodera, T.; Morino, K.; Tokishita, S.; Morita, R.; Masui, R.; Kuramitsu, S.; Ohta, T. Role of alkyltransferase-like (ATL) protein in repair of methylated DNA lesions in Thermus thermophilus. Mutagenesis 2011, 26, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/geq093.

- Rafferty, J.A.; Elder, R.H.; Watson, A.J.; Cawkwell, L.; Potter, P.M.; Margison, G.P. Isolation and partial characterisation of a Chinese hamster O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20, 1891–1895. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/20.8.1891.

- Gerson, S.L.; Trey, J.E.; Miller, K.; Berger, N.A. Comparison of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity based on cellular DNA content in human, rat and mouse tissues. Carcinogenesis 1986, 7, 745–749. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/7.5.745.

- Iyama, A.; Sakumi, K.; Nakabeppu, Y.; Sekiguchi, M. A unique structural feature of rabbit DNA repair methyltransferase as revealed by cDNA cloning. Carcinogenesis 1994, 15, 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/15.4.627.

- Leclere, M.M.; Nishioka, M.; Yuasa, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Takagi, M.; Imanaka, T. The O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus sp. KOD1: A thermostable repair enzyme. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1998, 258, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004380050708.

- Mattossovich, R.; Merlo, R.; Fontana, A.; d’Ippolito, G.; Terns, M.P.; Watts, E.A.; Valenti, A.; Perugino, G. A journey down to hell: New thermostable protein-tags for biotechnology at high temperatures. Extremophiles 2020, 24, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-019-01134-3.

- Adams, C.A.; Melikishvili, M.; Rodgers, D.W.; Rasimas, J.J.; Pegg, A.E.; Fried, M.G. Topologies of complexes containing O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 389, 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.067.

- Adams, C.A. and Fried, M.G. Mutations that probe the cooperative assembly of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase complexes. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 1590–1598. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi101970d.

- Melikishvili, M.; Rasimas, J.J.; Pegg, A.E.; Fried, M.G. Interactions of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) with short double-stranded DNAs. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 13754–13763. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi801666c.

- Melikishvili, M. and Fried, M.G. Resolving the contributions of two cooperative mechanisms to the DNA binding of AGT. Biopolymers 2015, 103, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.22684.

- Rasimas, J.J.; Kar, S.R.; Pegg, A.E.; Fried, M.G. Interactions of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) with short single-stranded DNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 3357–3366. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M608876200.

- Kono, S.; van den Berg, A.; Simonetta, M.; Mukhortava, A.; Garman, E.F.; Tessmer, I. Resolving the subtle details of human DNA alkyltransferase lesion search and repair mechanism by single-molecule studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2116218119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116218119.

- Melikishvili, M. and Fried, M.G. Lesion-specific DNA-binding and repair activities of human O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 9060–9072. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks674.

- Melikishvili, M. and Fried, M.G. Quaternary interactions and supercoiling modulate the cooperative DNA binding of AGT. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 7226–7236. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx223.

- Rasimas, J.J.; Pegg, A.E.; Fried, M.G. DNA-binding mechanism of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Effects of protein and DNA alkylation on complex stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 7973–7980. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M211854200.

- Tessmer, I. and Fried, M.G. Insight into the cooperative DNA binding of the O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase. DNA Repair 2014, 20, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.01.006.

- Niture, S.K.; Doneanu, C.E.; Velu, C.S.; Bailey, N.I.; Srivenugopal, K.S. Proteomic analysis of human O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by affinity chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 337, 1176–1184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.177.

- Choi, J.Y.; Chowdhury, G.; Zang, H.; Angel, K.C.; Vu, C.C.; Peterson, L.A.; Guengerich, F.P. Translesion synthesis across O6-alkylguanine DNA adducts by recombinant human DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 38244–38256. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M608369200.

- Du, H.; Wang, P.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. Repair and translesion synthesis of O6-alkylguanine DNA lesions in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11144–11153. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA119.009054.

- Roos, W.; Baumgartner, M.; Kaina, B. Apoptosis triggered by DNA damage O6-methylguanine in human lymphocytes requires DNA replication and is mediated by p53 and Fas/CD95/Apo-1. Oncogene 2004, 23, 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1207080.

- Teo, A.K.; Oh, H.K.; Ali, R.B.; Li, B.F. The modified human DNA repair enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase is a negative regulator of estrogen receptor-mediated transcription upon alkylation DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 7105–7114. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.21.20.7105-7114.2001.

- Ali, R.B.; Teo, A.K.; Oh, H.K.; Chuang, L.S.; Ayi, T.C.; Li, B.F. Implication of localization of human DNA repair enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase at active transcription sites in transcription-repair coupling of the mutagenic O6-methylguanine lesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 1660–1669. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.18.3.1660.

- Bronstein, S.M.; Skopek, T.R.; Swenberg, J.A. Efficient repair of O6-ethylguanine, but not O4-ethylthymine or O2-ethylthymine, is dependent upon O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and nucleotide excision repair activities in human cells. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 2008–2011.

- Taira, K.; Kaneto, S.; Nakano, K.; Watanabe, S.; Takahashi, E.; Arimoto, S.; Okamoto, K.; Schaaper, R.M.; Negishi, K.; Negishi, T. Distinct pathways for repairing mutagenic lesions induced by methylating and ethylating agents. Mutagenesis 2013, 28, 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/get010.

- Yamada, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Okamoto, K.; Arimoto, S.; Takahashi, E.; Nigishi, K.; Negishi, T. Chloroethylating anticancer drug-induced mutagenesis and its repair in Escherichia coli. Genes Environ. 2019, 41, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41021-019-0123-x.

- Cropper, J.D.; Alimbetov, D.S.; Brown, K.T.G.; Likhotvorik, R.I.; Robles, A.J.; Guerra, J.T.; He, B.; Chen, Y.; Kwon, Y.; Kurmasheva, R.T. PARP1-MGMT complex underpins pathway crosstalk in O6-methylguanine repair. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01367-4.

- London, R.E. XRCC1—Strategies for coordinating and assembling a versatile DNA damage response. DNA Repair 2020, 93, 102917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2020.102917.

- Pascal, J.M. The comings and goings of PARP-1 in response to DNA damage. DNA Repair 2018, 71, 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.08.022.

- Tessmer, I. The roles of non-productive complexes of DNA repair proteins with DNA lesions. DNA Repair 2023, 129, 103542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2023.103542.

- Wei, H. and Yu, X. Functions of PARylation in DNA Damage Repair Pathways. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2016, 14, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2016.05.001.

- Whitaker, A.M.; Schaich, M.A.; Smith, M.R.; Flynn, T.S.; Freudenthal, B.D. Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage: From mechanism to disease. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2017, 22, 1493–1522. https://doi.org/10.2741/4555.

- Srivenugopal, K.S.; Mullapudi, S.R.; Shou, J.; Hazra, T.K.; Ali-Osman, F. Protein phosphorylation is a regulatory mechanism for O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase in human brain tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 282–287.

- Raghavan, S.; Baskin, D.S.; Sharpe, M.A. A “Clickable” Probe for Active MGMT in Glioblastoma Demonstrates Two Discrete Populations of MGMT. Cancers 2020, 12, 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12020453.

- Mullapudi, S.R.; Ali-Osman, F.; Shou, J.; Srivenugopal, K.S. DNA repair protein O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase is phosphorylated by two distinct and novel protein kinases in human brain tumour cells. Biochem. J. 2000, 351 Pt 2, 393–402.

- Peng, Y. and Pei, H. DNA alkylation lesion repair: Outcomes and implications in cancer chemotherapy. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2021, 22, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B2000344.

- Longhurst, S.J.; Rafferty, J.A.; Arrand, J.R.; Cortez, N.; Giraud, C.; Berns, K.I.; Fairbairn, L.J. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated expression of O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase protects human epithelial and hematopoietic cells against chloroethylating agent toxicity. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 301–310. https://doi.org/10.1089/10430349950019084.

- Jansen, M.; Bardenheuer, W.; Sorg, U.R.; Seeber, S.; Flasshove, M.; Moritz, T. Protection of hematopoietic cells from O6-alkylation damage by O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase gene transfer: Studies with different O6-alkylating agents and retroviral backbones. Eur. J. Haematol. 2001, 67, 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0609.2001.067001002.x.

- von Wronski, M.A.; Harris, L.C.; Tano, K.; Mitra, S.; Bigner, D.D.; Brent, T.P. Cytosine methylation and suppression of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase expression in human rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines and xenografts. Oncol. Res. 1992, 4, 167–174.

- Chen, J.M.; Zhang, Y.P.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Fujimoto, J.; Ikenaga, M. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity in human tumors. Carcinogenesis 1992, 13, 1503–1507. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/13.9.1503.

- Saad, A.A.; Kassem, H.; Povey, A.C.; Margison, G.P. Expression of O-Alkylguanine-DNA Alkyltransferase in Normal and Malignant Bladder Tissue of Egyptian Patients. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 840230. https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/840230.

- Povey, A.C.; Hall, C.N.; Cooper, D.P.; O’Connor, P.J.; Margison, G.P. Determinants of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity in normal and tumour tissue from human colon and rectum. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 85, 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000101)85:1<68::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-0.

- Kaina, B.; Margison, G.P.; Christmann, M. Targeting O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase with specific inhibitors as a strategy in cancer therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 3663–3681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-010-0491-7.

- Sun, G.; Bai, P.; Fan, T.; Zhao, L.; Zhong, R.; McElhinney, R.S.; McMurry, T.B.H.; Donnelly, D.J.; McCormick, J.E.; Kelly, J.; et al. QSAR and Chemical Read-Across Analysis of 370 Potential MGMT Inactivators to Identify the Structural Features Influencing Inactivation Potency. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2170. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15082170.

- Berg, S.L.; Gerson, S.L.; Godwin, K.; Cole, D.E.; Liu, L.; Balis, F.M. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of O6-benzylguanine and time course of peripheral blood mononuclear cell O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase inhibition in the nonhuman primate. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 4606–4610.

- Wedge, S.R. and Newlands, E.S. O6-benzylguanine enhances the sensitivity of a glioma xenograft with low O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity to temozolomide and BCNU. Br. J. Cancer 1996, 73, 1049–1052. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1996.203.

- Kokkinakis, D.M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Chendil, D.; Moschel, R.C.; Pegg, A.E. Sensitization of pancreatic tumor xenografts to carmustine and temozolomide by inactivation of their O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase with O6-benzylguanine or O6-benzyl-2′-deoxyguanosine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 3801–3807.

- Clemons, M.; Kelly, J.; Watson, A.J.; Howell, A.; McElhinney, R.S.; McMurry, T.B.; Margison, G.P. O6-(4-bromothenyl)guanine reverses temozolomide resistance in human breast tumour MCF-7 cells and xenografts. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 93, 1152–1156. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602833.

- Zhu, R.; Seow, H.A.; Baumann, R.P.; Ishiguro, K.; Penketh, P.G.; Shyam, K.; Sartorelli, A.C. Design of a hypoxia-activated prodrug inhibitor of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 6242–6247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.008.

- Wei, G.; Loktionova, N.A.; Pegg, A.E.; Moschel, R.C. Beta-glucuronidase-cleavable prodrugs of O6-benzylguanine and O6-benzyl-2’-deoxyguanosine. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm0493865.

- Reinhard, J.; Eichhorn, U.; Wiessler, M.; Kaina, B. Inactivation of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by glucose-conjugated inhibitors. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 93, 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.1336.

- Burri, S.H.; Gondi, V.; Brown, P.D.; Mehta, M.P. The Evolving Role of Tumor Treating Fields in Managing Glioblastoma: Guide for Oncologists. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 41, 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000395.

- Lazaridis, L.; Bumes, E.; Cacilia Spille, D.; Schulz, T.; Heider, S.; Agkatsev, S.; Schmidt, T.; Blau, T.; Oster, C.; Feldheim, J.; et al. First multicentric real-life experience with the combination of CCNU and temozolomide in newly diagnosed MGMT promoter methylated IDH wildtype glioblastoma. Neurooncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac137. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdac137.

- Han, X.; Abdallah, M.O.E.; Breuer, P.; Stahl, F.; Bakhit, Y.; Potthoff, A.L.; Pregler, B.E.F.; Schneider, M.; Waha, A.; Wullner, U.; et al. Downregulation of MGMT expression by targeted editing of DNA methylation enhances temozolomide sensitivity in glioblastoma. Neoplasia 2023, 44, 100929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2023.100929.

- Davis, B.M.; Reese, J.S.; Koc, O.N.; Lee, K.; Schupp, J.E.; Gerson, S.L. Selection for G156A O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase gene-transduced hematopoietic progenitors and protection from lethality in mice treated with O6-benzylguanine and 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 5093–5099.

- Woolford, L.B.; Southgate, T.D.; Margison, G.P.; Milsom, M.D.; Fairbairn, L.J. The P140K mutant of human O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) confers resistance in vitro and in vivo to temozolomide in combination with the novel MGMT inactivator O6-(4-bromothenyl)guanine. J. Gene Med. 2006, 8, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgm.816.

- Adair, J.E.; Beard, B.C.; Trobridge, G.D.; Neff, T.; Rockhill, J.K.; Silbergeld, D.L.; Mrugala, M.M.; Kiem, H.P. Extended survival of glioblastoma patients after chemoprotective HSC gene therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 133ra157. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003425.

- Adair, J.E.; Johnston, S.K.; Mrugala, M.M.; Beard, B.C.; Guyman, L.A.; Baldock, A.L.; Bridge, C.A.; Hawkins-Daarud, A.; Gori, J.L.; Born, D.E.; et al. Gene therapy enhances chemotherapy tolerance and efficacy in glioblastoma patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 4082–4092. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI76739.