Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Adam R. Szromek.

The topic of cultural heritage is the subject of many interdisciplinary studies. So far, these studies have focused on the issues of classifying particular types of heritage, their functions and benefits, components and determinants. However, relatively less attention was paid to the dimension of a methodical approach to education and rebuilding cultural identity through heritage. Meanwhile, generational changes, especially in the dimension of knowledge perception, indicate such a need.

- open innovation

- cultural heritage

- cultural identity

- generation

1. The Definition of Heritage

It is difficult to clearly define heritage, as well as other concepts in social sciences. As F. Benhamou [1] states, heritage is a social construction whose boundaries are unstable and blurred. Perhaps this argument is also an introduction to explaining the difficulties in using open innovations in the field of cultural heritage.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines heritage as “property which is or may be inherited; heritage”, “valuable things, such as historic buildings, that have been passed down from generation to generation” and “referring to things of historical or cultural value that are worth preserving” [2]. Heritage is something that can be passed down from generation to generation, something that can be preserved or inherited and something that has historical or cultural value. Heritage can be understood as a physical “object”: a piece of property, a building or a place that can be “owned” and “transferred” to someone else [2]. The extended definition considers heritage as intertwined forms of tangible heritage, such as buildings, monuments and works of art. But it also covers the intangible or living heritage, including folklore, cultural memories, celebrations and traditions, and natural heritage or cultural landscapes and sites of significant biodiversity [3]. It is also an extension of the definition proposed by UNESCO [4] under the Convention adopted in Paris on 16 November 1972, stating that cultural heritage is:

-

Monuments, including works of architecture, sculpture, painting, archaeological elements, which are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

-

Groups of buildings that include buildings that, because of their architecture, homogeneity or place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

-

Places, in the sense of works of man or of nature and man, and areas that are of Outstanding Universal Value from a historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view.

Speaking about heritage, it should be noted that this term is closely related to values (e.g., social, artistic, historical, scientific and spiritual) which have long been at the basis of the concept of heritage and its protection [5].

Other classifications of heritage are also described in the literature on the subject. For example, the following types of heritage can be cited: official, i.e., heritage that is legally and procedurally recognized as heritage and is entered into a register (e.g., [6]), tangible and intangible [2][3], inherent [3], natural/scientific (e.g., [7]), industrial (e.g., [8][9][10]), cultural (e.g., [11][12]) and digital cultural heritage (e.g., [13][14]), cultural sports [15] or agricultural [16], as well as gastronomy, as gastronomy is part of cultural heritage (e.g., [17]). Specializations of this term are also used, for example, the heritage of buildings, which is part of tangible heritage (cf. [18]).

Individual types of heritage are sometimes defined either in a narrower or broader sense. For example, industrial heritage defined more broadly includes industrial production and industrial-related construction, transport, education, services and other related industries. It also includes the related developments of new energy, new technologies and new materials that have brought about major changes in society, as well as social places involved in industrial activities, such as workers’ home areas and places of worship [19]. Given the narrow sense, industrial heritage mainly refers to the industrial remains of production, processing, storage and transport, including metallurgy, coal industry and many other industrial categories and all kinds of industrial and ancillary buildings. From the perspective of the form of the object of study, industrial heritage has two forms: tangible and intangible [19].

2. The Concept of Cultural Identity

Cultural identity refers to a sense of solidarity with the ideals of a particular cultural group, leading to approval of its beliefs, attitudes and behaviors [20]. Cultural identity “expresses the extent to which individuals share the values and attributes of the culture from which they come. It is a specific type of collective identity that, at the psychological level, unites individuals belonging to the same social group, while at the same time distinguishing them from members of other social groups” [21].

Cultural identity is a “common personality” developed, activated and modified by social actors in the context of social and historical interactions according to specific problems that prompt them to act [22].

Analyzing the etymology of this concept, it should be noted that identity provides uspeople with an answer to the question who am I? It is based on relationships with others and is characterized by the meanings that individuals assign to themselves [23]). The definition of adaptive “identity” has two components: (a) a coherent personal identity (a set of goals, values and beliefs that are internally consistent with each other); and (b) a coherent social identity (including cultural identity) [24].

In turn, the word “culture” has many more diverse definitions. It is an ambiguous concept and therefore difficult to define due to its multidimensional nature [25]). However, in the case of identity, an appropriate definition may be that taken from anthropology. Culture is defined there as “a comprehensive unit that contains knowledge, belief, art, morality, laws, customs and other abilities and habits which an individual adopts as a member of a given society” [26].

3. Intergenerational Differences

Actively learning about cultural heritage (not necessarily your own heritage) often becomes the first step to discovering or rediscovering your personal cultural identity. Although undertaking such cognitive activity often results from curiosity about different cultures, it is undoubtedly also closely related to the appreciation of cultural heritage [27], and what requires personal involvement may go beyond various social frameworks, including generational ones. For this reason, the challenge is not only to preserve identity but often to revive a lost identity while facing current challenges and embracing new demands and trends [28]. These challenges may undoubtedly include generational differences and especially the impact of Internet technologies on the conditions of growing up of subsequent generations. Therefore, an individual approach to discovering cultural identity in individual generations of modern societies seems to be an important issue. This topic is present in the literature in various contexts, which proves significant differences in the perception of reality by representatives of different generations. To highlight the identified intergenerational differences, the demographic classification adopted in the literature (e.g., [29][30]), which lists eight generational groups, i.e., groups of people born in a specific period of time, who are linked by specific socio-cultural conditions, has been used. The classification characterizes individual generations starting from 1883, and among them, the first three are pre-war generations, i.e., Lost Generation (1883–1900), Greatest Generation (1901–1927) and Silent Generation (1928–1945) [31][32]. These are generations whose representatives are largely dead, which is why most research is conducted on post-war generations. The first generational group, born shortly after WWII, i.e., in 1945–1964, is the Baby Boomers. This is the generation of the post-war population boom, among whom the main group is modern retirees but also professionally active people at the end of their careers. This makes it a socially and financially established group, focused on recreational and health goals. It can be expected that their cognitive need for the past presented by cultural heritage, and especially industrial heritage, will often be associated with memories and personal contact with places, objects or machines and devices that are currently museum exhibits. At the same time, this generation is the most distanced from the achievements of the digital revolution out of the five post-war generations, and the most related to direct interaction with another person. The second considered generation is Generation X, whose members were born in the years 1965–1980. They are, therefore, the last generation brought up without the Internet and without mobile phones but at the same time are very entrepreneurial, with the ability to adapt to a difficult situation, which results from the difficult economic conditions of the 1980s and 1990s, in which they grew up [33]. Their attitude towards cultural heritage may result from several essential characteristics. First of all, this is a generation in which the family, and thus the intergenerational bond, is of great importance. This may mean being able to share one’s own heritage with the next generation, but also passing on a commitment to a personal cultural identity to the next generation. In learning about cultural heritage, this generation may partly refer to personal memories, but rather in relation to the functioning of their parents and grandparents, rather than their own. The third generation is Millennials, i.e., representatives of Generation Y, whose community was born between 1981 and 1994. This means that they have been shaped by the experiences of the primary processes of globalization and the digital revolution. This is a social group that tolerates multiculturalism well and often does not even imagine state or mental borders, neither in terms of access to consumer goods and services nor in mobility. Migration and communication processes do not constitute any barriers for them; therefore, their relations are less local and more often global. As the generation directly preceding the digital era, and thus brought up in its initial period, they are characterized by a great ability to undertake travel and share travel experiences online [34]. The literature shows that Generation Y is more active than previous generations, and at the same time, better organized in terms of the use of Internet tools for this purpose [35]. Generation Z is the fourth post-war generation, the beginning of which coincides with the digital revolution, as it covers the period from 1995 to 2010. The uniqueness of this generation is related to the approach to communication tools developed by the digital approach, especially social media. It is also their main form of communication, dominating over personal interactions [30]. It can be expected that this generation will look for motivation to learn about cultural heritage in social media. It is also an important area of social research related to the innovations being introduced. This opportunity is related to travel restrictions for several reasons. One of them is the financial reason resulting from the fact that they are the youngest professionally active generation, which affects their financial possibilities. However, another reason may be the possibility of satisfying the needs in an alternative way, not requiring a trip, but only using virtual reality. The third reason, although perhaps not the least, is the desire to protect the natural environment by limiting travel. The last generation whose members were born after 2010 is still children at the time of publishing the article. This generation was conventionally called the Alpha generation [36], whose members were born in the new millennium. There is also an interesting approach to the observed generational divide, in which the Gen-C (as connected to the Internet) [37] generation stands out. However, this is not a generation determined by age but by psychographic features that define their behavior, values, attitudes and lifestyle related to digital technologies.4. Impact of Heritage on Education and Cultural Identity by Using of Open Innovation

The role of heritage in education is appreciated by subsequent researchers. A broad review of the literature on heritage in educational discourses is published by O. Fontal et al. [38]. The authors, based on 223 publications on this topic, identified as many as five areas of research. These are:-

Heritage education in formal education;

-

Heritage education, cultural heritage, and educational innovation;

-

Archaeological heritage education;

-

Heritage education, case studies, and historical awareness;

-

Heritage education, and classified research genealogies and methodologies.

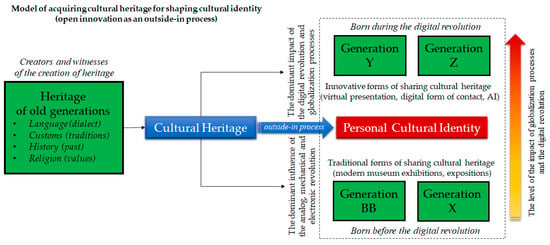

Figure 1.

Model of acquiring cultural heritage for shaping cultural identity.

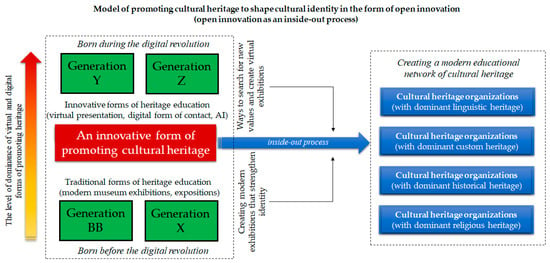

Figure 2.

Model of sharing cultural heritage to shape cultural identity in the form of open innovation.

References

- Benhamou, F. Heritage. In Handbook of Cultural Economics, 3rd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishings: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 279–286.

- Harrison, R. What is heritage. In Understanding the Politics of Heritage; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2010; pp. 5–42.

- Ahmad, Y. The scope and definitions of heritage: From tangible to intangible. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2006, 12, 292–300.

- UNESCO. United Nations Educational, Scientific And Cultural Organisation, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Adopted by the General Conference at Its Seventeenth Session Paris, 16 November 1972, Art. 1; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972.

- Avrami, E.; Macdonald, S.; Mason, R.; Myers, D. (Eds.) Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019.

- Kang, S.; Hwang, J. An Investigation into the Performance of an Ambidextrously Balanced Innovator and Its Relatedness to Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 23.

- Zhang, Z.; Xiong, K.; Huang, D. Natural world heritage conservation and tourism: A review. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 55.

- Kerstetter, D.; Confer, J.; Bricker, K. Industrial heritage attractions: Types and tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 91–104.

- Wang, X.; Huang, Z. Construction Strategies of Industrial Heritage Tourism Complex from Multiple Perspectives. J. Landsc. Res. 2023, 15, 89–92.

- Della Lucia, M.; Pashkevich, A. A sustainable afterlife for post-industrial sites: Balancing conservation, regeneration and heritage tourism. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 641–661.

- Brooks, C.; Waterton, E.; Saul, H.; Renzaho, A. Exploring the relationships between heritage tourism, sustainable community development and host communities’ health and wellbeing: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282319.

- Dong, B.; Bai, K.; Sun, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y. Spatial distribution and tourism competition of intangible cultural heritage: Take Guizhou, China as an example. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 64.

- Chernbumroong, S.; Nadee, W.; Jansukpum, K.; Puritat, K.; Julrode, P. The Effects of Gamified Exhibition in a Physical and Online Digital Interactive Exhibition Promoting Digital Heritage and Tourism. TEM J. 2022, 11, 1520–1530.

- Li, H.; Ito, H. Visitor’s experience evaluation of applied projection mapping technology at cultural heritage and tourism sites: The case of China Tangcheng. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 52.

- Wilson, J.P. Homes of sports: A study of cultural heritage tourism and football. J. Sport Tour. 2022, 26, 315–333.

- Lee, C.-K.; Olya, H.; Park, Y.-N.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Kim, M.J. Sustainable intelligence and cultural worldview as triggers to preserve heritage tourism resources. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 899–918.

- Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Grubor, B.; Banjac, M.; Đerčan, B.; Tešanović, D.; Šmugović, S.; Radivojević, G.; Ivanović, V.; Vujasinović, V.; Stošić, T. The Sustainability of Gastronomic Heritage and Its Significance for Regional Tourism Development. Heritage 2023, 6, 3402–3417.

- Al-Sakkaf, A.; Zayed, T.; Bagchi, A. A review of definition and classification of heritage buildings and framework for their evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on New Horizons in Green Civil Engineering (NHICE-02), Victoria, BC, Canada, 29 April–1 May 2020; pp. 24–26.

- Yang, L. Study on the Development Model of the Combination of “Third-Tier” Industrial Heritage and Rural Tourism under the Concept of Urban Image. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 2730532.

- Warne, A.D. Ethnic and Cultural Identity: Perceptions, Discrimination and Social Challenges; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2015.

- Peng, A.C.; Van Dyne, L.; Oh, K. The Influence of Motivational Cultural Intelligence on Cultural Effectiveness Based on Study Abroad: The Moderating Role of Participant’s Cultural Identity. J. Manag. Educ. 2015, 39, 572–596.

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, W. The Impact of Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity in the Brand Value of Agricultural Heritage: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 79.

- Bataille, C.D.; Vough, H.C. More Than the Sum of My Parts: An Intrapersonal Network Approach to Identity Work in Response to Identity Opportunities and Threats. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2022, 47, 93–115.

- Schwartz, S.J.; Montgomery, M.J.; Briones, E. The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Hum. Dev. 2006, 49, 1–30.

- Behrens, P. Curing Culture Cancer: Positive Work Culture or Curing Your Culture’s Cancer? J. Bus. Agil. 2022, 3, 18–22.

- Delpechitre, D.; David, S.B. Cross-Cultural Selling: Examining the Importance of Cultural Intelligence in Sales Education. J. Mark. Educ. 2017, 39, 94–108.

- Hernández González, A.d.M.; Iturbe Vargas, M. La repercusión del turismo en la identidad cultural de los Pueblos Mágicos de Chiapas. Hosp. ESDAI 2019, 36, 5–41.

- Aziz, N.A.E. Historic Identity Transformation in Cultural Heritage Sites the Story of Orman Historical Garden in Cairo City, Egypt. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 12, 81–98.

- Lissitsa, S.; Zychlinski, E.; Kagan, M. The Silent Generation vs Baby Boomers: Socio-demographic and psychological predictors of the “gray” digital inequalities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 128, 107098.

- Szromek, A.R.; Hysa, B.; Karasek, A. The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7151.

- Arsenault, P.M. Validating generational differences: A legitimate diversity and leadership issue. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2004, 25, 124–141.

- Dolot, A. The characteristics of Generation Z. E-mentor 2018, 2, 44–50.

- Zabel, K.L.; Biermeier-Hanson, B.B.J.; Baltes, B.B.; Early, B.J.; Shepard, A. Generational Differences in Work Ethic: Fact or Fiction? J. Bus. Psychol. Sci. Bus. Media 2016, 32, 301–315.

- Xiang, Z.; Magnini, V.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Information Technology and Consumer Behaviour in Travel and Tourism: Insights from Travel Planning Using the Internet. J. Retail.-Ing Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 244–249.

- Sun, S.; Nang Fong, L.H.; Law, R.; Luk, C. An An Investigation of Gen-Y’s Online Hotel Information Search: The Case of Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 443–456.

- Azimirad, A. Pregnancy in adolescence; It is time to get ready for generations Z and Alpha. Gynecol. Obstet. Clin. Med. 2023, 3, 71–75.

- A Research Report. Generating Success with Generation, C. Infomentum. Making Change Work. March 2014. Available online: https://www.infomentum.com/genc (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Fontal, O.; Martínez-Rodríguez, M.; García-Ceballos, S. The Educational Dimension as an Emergent Topic in the Management of Heritage: Mapping Scientific Production, 1991–2022. Heritage 2023, 6, 7126–7139.

- Simsek, G.; Elitok Kesici, A. Heritage education for primary school children through drama: The case of Aydin, Turkey. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 3817–3824.

- Mendoza, R.; Baldiris, S.; Fabregat, R. Framework to Heritage Education using Emerging Technologies. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 75, 239–249.

- Manca, S.; Raffaghelli, J.E.; Sangra, A. A learning ecology-based approach for enhancing Digital Holocaust Memory in European cultural heritage education. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19286.

- Lucas-Palacios, L.; Trabajo-Rite, M.; Delgado-Algarra, E.J. Heritage education in initial teacher training from a feminist and animal ethics perspective. A study on critical-empathic thinking for social change. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 129, 104153.

- Ott, M.; Pozzi, F. Towards a new era for Cultural Heritage Education: Discussing the role of ICT. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1365–1371.

- Shafiei, M.; Hakaki, N.A. A Multi-Dimensional Causal Model of Effective Factors on Open Innovation in Manufacturing SMEs in Iran. Int. J. Asian Bus. Inf. Manag. 2019, 10, 91–110.

- Szczepański, M.S.; Ślęzak-Tazbir, W. Region i społeczność lokalna w perspektywie socjologicznej. In Edukacja Kulturowa. Przestrzeń—Kultura—Przekaz; Brzezińska, A.W., Hulewska, A., Słomska-Nowak, J., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Zarządzania “Edukacja”: Wrocław, Poland, 2009.

- Żmijewska, E. Tożsamość kulturowa (narodowa, etniczna): Przyczynek do dyskusji o pojęciach: Na przykładzie Ślązaków i Kaszubów. Pedagog. Przedszkolna Wczesnoszkolna 2014, 2, 7–24.

- Dictionary of Sociology and Social Sciences ; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; pp. 402–403.

- Mielicka-Pawłowska, H. Ethnos as a Basis of Cultural Identity. Humanistyka Przyrodozn. 2018, 24, 193–209.

More