You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Fanny Huang and Version 1 by Hinh Ly.

Influenza virus infections occur in people and animals worldwide and cause variable disease outcomes depending on the species affected and strain of the virus. Influenza viruses can be transmitted between animals, persons, or from animals to humans and can cause severe disease pathology or death.

- influenza virus

- IAV

- IBV

- pathology

1. Introduction

The family Orthomyxoviridae encompasses four genera of influenza viruses: Alphainfluenzavirus (influenza A virus, IAV), Betainfluenzavirus (influenza B virus, IBV), Gammainfluenzavirus (influenza C virus, ICV), and Deltainfluenzavirus (influenza D virus, IDV) [1]. Influenza virus infections occur in people and animals worldwide and cause variable disease outcomes depending on the species affected and strain of virus. IAV and IAB infect humans and are responsible for seasonal influenza (flu) epidemics that result in 3–5 million severe illnesses and 290,000–650,000 deaths yearly worldwide [2]. Global flu pandemics, due to the introduction of new, antigenically distinct IAV strains in immunologically naïve populations, occur sporadically and cause increased morbidity and mortality [3]. IAV has a broad host range, infecting aquatic birds, domestic poultry, pigs, dogs, horses, bats, and people. Aquatic birds are considered the reservoir species and likely source of pandemic IAV in humans [4]. In contrast, IBV and ICV are primarily human pathogens, although IBV has been isolated from seals [5] and ICV from cattle [6], pigs [7], and dogs [8]. Infection with ICV is less common and mainly affects children [9]. IDV is a newly emerging virus detected in pigs [10] and cattle [11] with potential zoonotic risk [12].

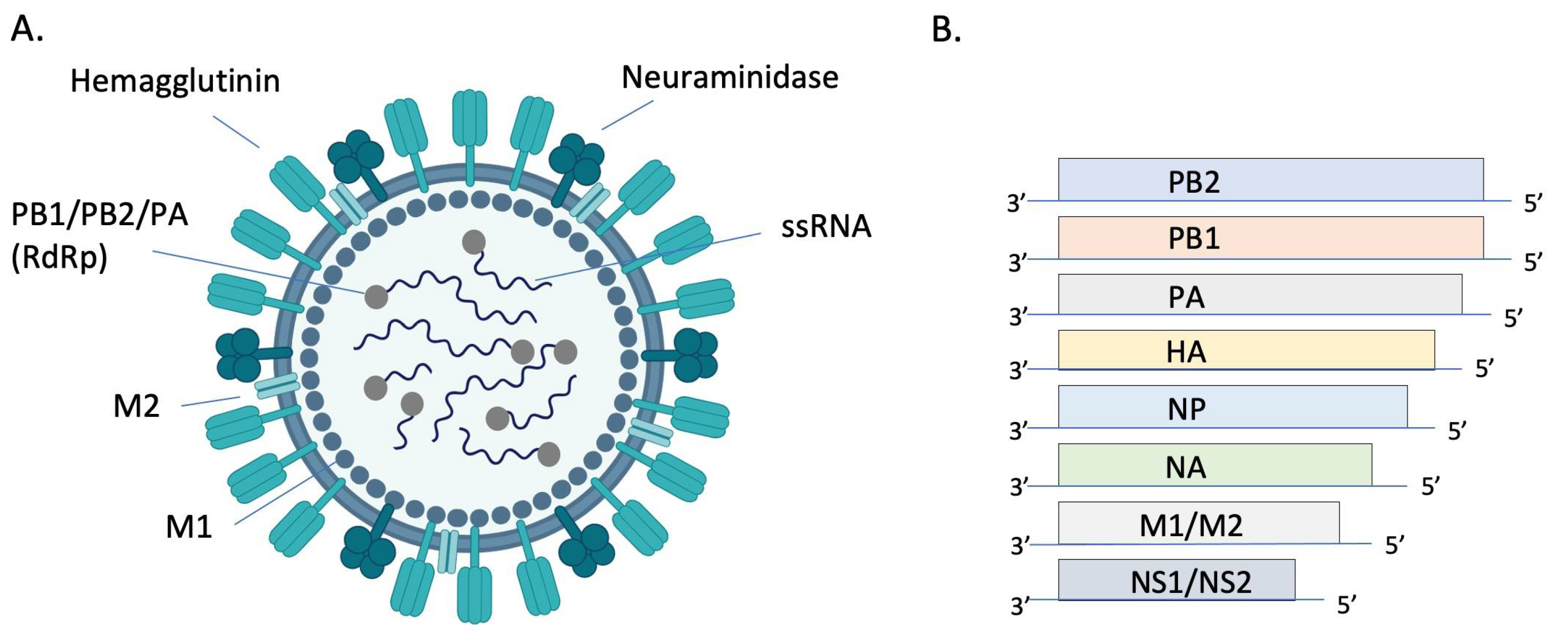

Orthomyxoviruses are enveloped, segmented, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA viruses. There are either 8 (IAV and IBV) or 7 (ICV and IDV) genome segments (Figure 1). The envelope of IAV and IBV is studded with the transmembrane glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), which are responsible for attachment/penetration and virion release, respectively. IAVs are classified into subtypes based on their HA and NA molecules, of which there are 18 (HA) and 11 (NA) currently identified. All but two subtypes of IAV are found in aquatic birds while only H1N1 and H3N2 currently circulate in humans [13]. HA and NA are immunodominant epitopes with HA serving as the major target of neutralizing antibodies [14]. Random point mutations in HA and NA, due to the error-prone RNA polymerase, cause slow and gradual antigenic changes (antigenic drift) whereas genetic reassortment via exchange of gene segments results in new, antigenically distinct strains of virus (antigenic shift). These strategies allow the virus to evade host immune responses and develop resistance to antivirals. The possibility of zoonotic transmission and emergence of new pathogenic influenza strains of pandemic potential poses a significant public health threat.

Figure 1. Structure and genomic organization of influenza A virus. The virion (A) consists of 8 negative sense ssRNA segments complexed with the nucleoprotein (NP, not pictured) to form the helical ribonucleoprotein (RNP). Each segment is associated with an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) complex composed of basic protein 1 (PB1), basic protein 2 (PB2), and the acidic protein (PA). Envelope-associated proteins include hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), matrix protein (M1), and the integral membrane protein (M2). Genomic segments 1–7 encode for one of these structural proteins and the 8th segment encodes for nonstructural proteins (NS) (B). Image (A) created with BioRender.com.

In addition to the expected annual flu burden, pandemic influenza viruses have emerged every 10–40 years due to the reassortment of human IAVs with gene segments of avian and/or swine origin [15]. These novel viruses result in increased morbidity and mortality due to lack of preexisting immunity in human populations [16]. The 1918 H1N1 “Spanish flu” was the deadliest pandemic in history, causing over 40 million deaths worldwide [17]. In addition to the human influenza viruses causing seasonal and pandemic disease, people are sporadically infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses of the H5 or H7 subtype, resulting in approximately 1000 deaths to date [18] and mortality rates of up to 60% [19].

Influenza viruses are transmitted by inhalation of droplets and/or aerosols and by direct contact with an infected individual or contaminated surface [20]. Prevention strategies include nonpharmaceutical interventions such as hand washing, use of hand sanitizer [21[21][22],22], social distancing, cough and sneeze hygiene, and cleaning of potentially contaminated surfaces [3]. Vaccination remains the most effective way of preventing disease. Efficacy of inactivated and live attenuated vaccines typically varies between 40–60% [23] depending on the age and health status of an individual, virulence of the season’s major strains of virus, and how well that season’s vaccine matches circulating strains [3]. Antivirals play an important role in combating disease, although drug resistance is a major challenge. Continued research efforts to develop universal influenza vaccines and novel antivirals are essential to combat this highly infectious and potentially fatal disease.

2. Influenza Pathology

Influenza viruses enter host cells by binding of HA to sialic acid residues on glycoproteins and glycolipids. Binding affinity for specific sialic acid residues is an important determinant of host range, tissue tropism, and the potential for cross-species transmission (recently reviewed in ref [39][24]). In short, human influenza viruses preferentially bind to sialic acids with an α2,6 linkage to galactose (SAα2,6Gal) whereas avian influenza viruses preferentially bind to α2,3 linkages (SAα2,3Gal) [40][25]. In people, SAα2,6Gal is found predominantly in the upper airway and SAα2,3Gal mainly in the lower airway [41][26]. In contrast, birds express SAα2,3Gal predominantly in the upper airway and intestinal tract [42][27]. Thus, mutations that allow avian influenza viruses to bind to SAα2,6Gal in the upper respiratory tract of people are likely required for efficient human-to-human transmission via respiratory droplets and aerosols. Influenza viruses replicate in the nucleus of respiratory and intestinal epithelial cells. Replication peaks at 48 h after infection and virus is shed for approximately 6–8 days [43][28]. Severity of disease is associated with viral replication in the lower respiratory tract [25][29]. While symptoms result from a combination of virus-mediated damage to epithelial cells and host immune responses (immunopathology), it is generally accepted that immunopathology plays the largest role in tissue damage [44][30]. Infected epithelial cells and innate immune cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that are important to control infection, but also lead to bystander damage to epithelial and endothelial cells. Excess neutrophil recruitment [45,46][31][32] and inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNFα, CXCL10, IL-2R, GCSF, MCP1, and MIP1α are associated with disease severity and poor outcomes [35,47,48,49][33][34][35][36]. Because lung specimens are usually collected during autopsy, pathology is only documented in fatal cases of human IAV infection. Characteristic findings of viral pneumonia are similar between pandemic and non-pandemic years [25,32,34,50,51,52,53,54][29][37][38][39][40][41][42][43] so are described together. Grossly, the trachea and bronchi are hemorrhagic and often filled with blood-tinged, foamy fluid. The lungs are dark red and edematous, reflecting the underlying hemorrhagic bronchopneumonia that is frequently complicated by secondary bacterial infection [32,34,53][37][38][42]. Histologically, the trachea and bronchi have epithelial necrosis and desquamation in addition to submucosal edema, congestion, and hemorrhage. In the lower airways, there is necrotizing bronchiolitis and alveolitis, interstitial mononuclear inflammation, interstitial and alveolar edema, thrombi, hyaline membranes, and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia. These changes are consistent with the exudative phase of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), which is the histologic hallmark of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [55][44]. With time, epithelial regeneration, interstitial fibrosis, and bronchiolitis obliterans may develop. Secondary bacterial pneumonia consisting of overwhelming neutrophilic inflammation, extensive necrosis, and hemorrhage can obscure the underlying viral effects [25][29]. Hemophagocytosis is a prominent feature of some cases of fatal disease and is thought to be mediated by hypercytokinemia [33,51][40][45]. Hemophagocytosis was present in the lymph nodes of 18 of 36 (53%) pediatric patients dying of non-pandemic influenza [52][41] and in 25 of 41 (61%) patients dying of 2009 pH1N1 [33][45]. The clinical significance of hemophagocytosis in these infections is unclear. While overall histologic findings are similar in fatal cases from pandemic and non-pandemic years (Table 1), antigen distribution appears to differ. In a study of 47 pediatric patients dying of seasonal influenza pneumonia from 2003–2004, antigen was detected primarily in the bronchial epithelial cells and mucous glands of the trachea, bronchi, and large bronchioles [52][41]. In contrast, antigen was mainly present in type I and II alveolar pneumocytes in patients dying of 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) [33][45]. These findings likely reflect differences in tissue tropism based on receptor location and the variable course of disease at the time of sampling. As the case numbers are significantly lower compared with seasonal and pandemic H1N1, there are fewer reports on the pathology of fatal avian H5N1 infection despite a case fatality rate of 56% [56][46]. Diffuse alveolar damage is the main histologic feature and most cases also display mild lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, alveolar histiocytosis, hemorrhage, and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia [51,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64][40][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54]. Depending on the time course of disease, DAD may be exudative or organizing and fibrotic [62,63][52][53]. Extrapulmonary lesions including lymphoid depletion, hepatic necrosis, and acute tubular necrosis, are frequently reported [51,58,60,61,65][40][48][50][51][55]. Viral RNA can be detected outside of the respiratory tract in the spleen, liver, intestines [62[52][53][54],63,64], and cerebrospinal fluid [66][56] although extrapulmonary antigen is only rarely documented [61][51], suggesting that systemic spread may not be the culprit of multiorgan failure. In the respiratory tract, viral antigen and RNA are found most commonly in type I and II pneumocytes although they can also be present in macrophages, sloughed epithelial cells, non-ciliated and ciliated bronchiolar epithelium, and tracheal epithelium [57,58,60,61,62,63][47][48][50][51][52][53]. The predominant viral distribution in pneumocytes is consistent with the lower airway distribution of SAα2,3Gal, the receptor for avian influenza viruses [41][26]. Hemophagocytosis is a frequent finding in the lungs, lymph nodes, and spleen [51,57,58,60,61,63,64][40][47][48][50][51][53][54]. In severe cases, reactive hemophagocytic syndrome, consisting of pancytopenia, abnormal clotting times, and reduced liver function, is the most prominent finding [51,60][40][50]. A combination of high viral loads and an intense cytokine response appear central to the pathogenicity of H5N1 in people [57,67,68,69][47][57][58][59].Table 1.

Summary of clinical and pathologic findings in human and laboratory animal influenza infections.

| Common Animal Strain/Species | Virus Strain | Clinical Signs | Microscopic Pathology | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | N/A | Seasonal IAV | Varying degrees of fever, non-productive cough, dyspnea, coryza, fatigue, and myalgia (classic flu symptoms); vomiting and diarrhea in severe cases | Necrotizing tracheobronchitis and bronchointerstitial pneumonia with thrombi, edema, hemorrhage, hyaline membranes, and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (diffuse alveolar damage) | [25,26,50][29][39][60] |

| 2009 pH1N1 | Mild to severe flu symptoms | Same as seasonal IAV | [30,34,50,52][38][39][41][61] | ||

| 1918 H1N1 | Mild to severe flu symptoms | Same as seasonal IAV | [17,25,53][17][29][42] | ||

| HPAI H5N1 and H7N9 | Mild to severe flu symptoms with history of contact with live poultry | Same as seasonal IAV Extrapulmonary necrotic lesions are common and hemophagocytosis may be the most prominent lesion |

[19,35,1936,37,][3350,][3951,]70,71][[40][62][63][64][65] | ||

| Mouse | BALB/c C57BL/6 DBA/2J A/J |

PR8 | Dyspnea, ruffled fur, weight loss, and anorexia | Interstitial pneumonia, suppurative bronchiolitis and alveolitis, hyaline membranes, and alveolar edema | [72,73,74,75][66][67][68][69] |

| BALB/c C57BL/6 |

2009 pH1N1 | Variable weight loss (dose and strain dependent) | Histiocytic to neutrophilic bronchitis, bronchiolitis and alveolitis with varying epithelial necrosis (strain dependent) | [76,77,78,79][70][71][72][73] | |

| BALB/c | 1918 H1N1 | Weight loss and death | Interstitial pneumonia, suppurative bronchiolitis and alveolitis, hyaline membranes, and alveolar edema | [76,80,81][70][74][75] | |

| BALB/c DBA/2J |

HPAI H5N1 | Dyspnea, ruffled fur, weight loss, and anorexia | Interstitial pneumonia, suppurative bronchiolitis and alveolitis, hyaline membranes, and alveolar edema Encephalitis and myocardial necrosis |

[81,82,7683,]84,85,[77][78][7986,87,88][75][][80][81][82] | |

| C57BL/6 BALB/c |

H7N9 | Weight loss, ruffled fur, hunching | Bronchiolitis, patchy interstitial pneumonia, and varying amounts of bronchiolar and alveolar epithelial necrosis | [89,90,91,92][83][84][85][86] | |

| BALB/c | LPAI | Variable weight loss, ruffled fur, and hunching (strain dependent) | Necrotizing bronchitis and bronchiolitis with peribronchial pneumonia | [93,94,95,96,97][87][88][89][90][91] | |

| Hamster | Golden Syrian hamster | Seasonal IAV | Mild weight loss and temperature changes | None or mild necrotizing rhinitis and bronchopneumonia with perivascular cuffing | [98,99,100,101,102][92][93][94][95][96] |

| 2009 pH1N1 | Mild weight loss | Necrotizing rhinitis, bronchiolitis, perivasculitis, edema, and mild interstitial pneumonia | [101,103,104,105][95][97][98][99] | ||

| HPAI H5N1 | Not reported | Intranasal route: Bronchiolitis and bronchopneumonia Intragastric route: Interstitial pneumonia |

[106][100] | ||

| Ferret | Mustela putorius furo | Seasonal IAV | Asymptomatic or mild lethargy with sneezing, nasal discharge, and mild weight loss | Conventional intranasal model: Rhinitis and mild bronchiolitis and pneumoniaHigh dose intratracheal model: Moderate rhinitis and severe necrotizing bronchointerstitial pneumonia with edema | [107,108,,112][101109,][102110,][103][104]111[105][106] |

| 2009 pH1N1 | Lethargy, anorexia, dyspnea, and elevated body temperature | Necrotizing rhinotracheitis, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis with varying degrees of interstitial pneumonia and diffuse alveolar damage | [77,110,71][104]111,[105]112][[106] | ||

| 1918 H1N1 | Weight loss, sneezing, dyspnea, lethargy, and death | Necrotizing rhinitis, bronchiolitis and bronchointerstitial pneumonia with edema | [113,114,115][107][108][109] | ||

| HPAI H5N1 | Lethargy, anorexia, dyspnea, nasal discharge, sneezing, weight loss, elevated body temperature, diarrhea, and neurologic signs (ataxia, torticollis, and hind limb paresis) | Severe necrotizing bronchointerstitial pneumonia with diffuse alveolar damage Meningoencephalitis |

[111,116,117,118,119][105][110][111][112][113] | ||

| LPAI | Transiently elevated body temperature and weight loss; occasional dyspnea and lethargy | Suppurative rhinitis | [91,120,121][85][114][115] | ||

| NHP | Cynomolgus macaques (most common), rhesus macaques, and common marmosets | Seasonal IAV | Asymptomatic or mild lethargy | Mild bronchointerstitial pneumonia and peribronchiolitis | [122,123][116][117] |

| 2009 pH1N1 | Asymptomatic or mildly elevated body temperature and lethargy; tachypnea, dyspnea, and nasal discharge reported for some strains of virus | Suppurative rhinitis in mild cases; necrotizing bronchopneumonia with edema and hyaline membranes in severe cases (strain dependent) | [124,125,126,127,128,129][118][119][120][121][122][123] | ||

| 1918 H1N1 | Anorexia, lethargy, cough, nasal discharge, and tachypnea | Necrotizing bronchointerstitial pneumonia with hemorrhage, edema, and hyaline membranes | [123,130,131][117][124][125] | ||

| HPAI H5N1 | Anorexia, lethargy, cough, tachypnea, elevated body temperature, diarrhea, and thrombocytopenia | Necrotizing bronchointerstitial pneumonia with hemorrhage, edema, hyaline membranes, and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia Lymphoid necrosis and renal tubular necrosis |

[130,132,133,134][124][126][127][128] |

References

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.-D.; Chen, X.; Tian, J.-H.; Chen, L.-J.; Li, K.; Wang, W.; Eden, J.-S.; Shen, J.-J.; Liu, L.; et al. The Evolutionary History of Vertebrate RNA Viruses. Nature 2018, 556, 197–202.

- Influenza (Seasonal). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Krammer, F.; Smith, G.J.D.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Peiris, M.; Kedzierska, K.; Doherty, P.C.; Palese, P.; Shaw, M.L.; Treanor, J.; Webster, R.G.; et al. Influenza. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2018, 4, 3.

- Webster, R.G.; Bean, W.J.; Gorman, O.T.; Chambers, T.M.; Kawaoka, Y. Evolution and Ecology of Influenza A Viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56, 152–179.

- Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Martina, B.E.E.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Influenza B Virus in Seals. Science 2000, 288, 1051–1053.

- Zhang, H.; Porter, E.; Lohman, M.; Lu, N.; Peddireddi, L.; Hanzlicek, G.; Marthaler, D.; Liu, X.; Bai, J. Influenza C Virus in Cattle with Respiratory Disease, United States, 2016–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1926–1929.

- Guo, Y.J.; Jin, F.G.; Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.M. Isolation of Influenza C Virus from Pigs and Experimental Infection of Pigs with Influenza C Virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1983, 64 Pt 1, 177–182.

- Manuguerra, J.C.; Hannoun, C. Natural Infection of Dogs by Influenza C Virus. Res. Virol. 1992, 143, 199–204.

- Thielen, B.K.; Friedlander, H.; Bistodeau, S.; Shu, B.; Lynch, B.; Martin, K.; Bye, E.; Como-Sabetti, K.; Boxrud, D.; Strain, A.K.; et al. Detection of Influenza C Viruses Among Outpatients and Patients Hospitalized for Severe Acute Respiratory Infection, Minnesota, 2013–2016. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1092–1098.

- Hause, B.M.; Ducatez, M.; Collin, E.A.; Ran, Z.; Liu, R.; Sheng, Z.; Armien, A.; Kaplan, B.; Chakravarty, S.; Hoppe, A.D.; et al. Isolation of a Novel Swine Influenza Virus from Oklahoma in 2011 Which Is Distantly Related to Human Influenza C Viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003176.

- Hause, B.M.; Collin, E.A.; Liu, R.; Huang, B.; Sheng, Z.; Lu, W.; Wang, D.; Nelson, E.A.; Li, F. Characterization of a Novel Influenza Virus in Cattle and Swine: Proposal for a New Genus in the Orthomyxoviridae Family. mBio 2014, 5, e00031-14.

- White, S.K.; Ma, W.; McDaniel, C.J.; Gray, G.C.; Lednicky, J.A. Serologic Evidence of Exposure to Influenza D Virus among Persons with Occupational Contact with Cattle. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 81, 31–33.

- Influenza Type A Viruses|Avian Influenza (Flu). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/influenza-a-virus-subtypes.htm (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Brandenburg, B.; Koudstaal, W.; Goudsmit, J.; Klaren, V.; Tang, C.; Bujny, M.V.; Korse, H.J.W.M.; Kwaks, T.; Otterstrom, J.J.; Juraszek, J.; et al. Mechanisms of Hemagglutinin Targeted Influenza Virus Neutralization. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80034.

- Webster, R.G.; Govorkova, E.A. Continuing Challenges in Influenza. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1323, 115–139.

- Palese, P. Influenza: Old and New Threats. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S82–S87.

- Palese, P.; Tumpey, T.M.; Garcia-Sastre, A. What Can We Learn from Reconstructing the Extinct 1918 Pandemic Influenza Virus? Immunity 2006, 24, 121–124.

- Shi, J.; Zeng, X.; Cui, P.; Yan, C.; Chen, H. Alarming Situation of Emerging H5 and H7 Avian Influenza and Effective Control Strategies. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 12, 2155072.

- Gambotto, A.; Barratt-Boyes, S.M.; De Jong, M.D.; Neumann, G.; Kawaoka, Y. Human Infection with Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Influenza Virus. Lancet 2008, 371, 1464–1475.

- Killingley, B.; Nguyen-Van-Tam, J. Routes of Influenza Transmission. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2013, 7, 42–51.

- Stebbins, S.; Cummings, D.A.T.; Stark, J.H.; Vukotich, C.; Mitruka, K.; Thompson, W.; Rinaldo, C.; Roth, L.; Wagner, M.; Wisniewski, S.R.; et al. Reduction in the Incidence of Influenza A but Not Influenza B Associated with Use of Hand Sanitizer and Cough Hygiene in Schools: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011, 30, 921–926.

- Torner, N.; Soldevila, N.; Garcia, J.J.; Launes, C.; Godoy, P.; Castilla, J.; Domínguez, A.; CIBERESP Cases and Controls in Pandemic Influenza Working Group, Spain. Effectiveness of Non-Pharmaceutical Measures in Preventing Pediatric Influenza: A Case-Control Study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 543.

- CDC Seasonal Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Studies|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/effectiveness-studies.htm (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Zhao, C.; Pu, J. Influence of Host Sialic Acid Receptors Structure on the Host Specificity of Influenza Viruses. Viruses 2022, 14, 2141.

- Rogers, G.N.; Paulson, J.C.; Daniels, R.S.; Skehel, J.J.; Wilson, I.A.; Wiley, D.C. Single Amino Acid Substitutions in Influenza Haemagglutinin Change Receptor Binding Specificity. Nature 1983, 304, 76–78.

- Shinya, K.; Ebina, M.; Yamada, S.; Ono, M.; Kasai, N.; Kawaoka, Y. Influenza Virus Receptors in the Human Airway. Nature 2006, 440, 435–436.

- Pillai, S.P.; Lee, C.W. Species and Age Related Differences in the Type and Distribution of Influenza Virus Receptors in Different Tissues of Chickens, Ducks and Turkeys. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 5.

- Knipe, D.M.; Howley, P. Fields Virology; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4698-7422-7.

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Morens, D.M. The Pathology of Influenza Virus Infections. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008, 3, 499–522.

- Boyd, D.F.; Wilson, T.L.; Thomas, P.G. Chapter Seven—One Hundred Years of (Influenza) Immunopathology. In Advances in Virus Research; Carr, J.P., Roossinck, M.J., Eds.; Immunopathology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 107, pp. 247–284.

- Tang, B.M.; Shojaei, M.; Teoh, S.; Meyers, A.; Ho, J.; Ball, T.B.; Keynan, Y.; Pisipati, A.; Kumar, A.; Eisen, D.P.; et al. Neutrophils-Related Host Factors Associated with Severe Disease and Fatality in Patients with Influenza Infection. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3422.

- Guan, W.; Yang, Z.; Wu, N.C.; Lee, H.H.Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Shen, L.; Wu, D.C.; Chen, R.; Zhong, N.; et al. Clinical Correlations of Transcriptional Profile in Patients Infected with Avian Influenza H7N9 Virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1238–1248.

- Gao, H.-N.; Lu, H.-Z.; Cao, B.; Du, B.; Shang, H.; Gan, J.-H.; Lu, S.-H.; Yang, Y.-D.; Fang, Q.; Shen, Y.-Z.; et al. Clinical Findings in 111 Cases of Influenza A (H7N9) Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2277–2285.

- Fiore-Gartland, A.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; Agan, A.A.; Mistry, A.J.; Thomas, P.G.; Matthay, M.A.; PALISI PICFlu Investigators; Hertz, T.; Randolph, A.G. Cytokine Profiles of Severe Influenza Virus-Related Complications in Children. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1423.

- Bradley-Stewart, A.; Jolly, L.; Adamson, W.; Gunson, R.; Frew-Gillespie, C.; Templeton, K.; Aitken, C.; Carman, W.; Cameron, S.; McSharry, C. Cytokine Responses in Patients with Mild or Severe Influenza A(H1N1)Pdm09. J. Clin. Virol. 2013, 58, 100–107.

- Oshansky, C.M.; Gartland, A.J.; Wong, S.-S.; Jeevan, T.; Wang, D.; Roddam, P.L.; Caniza, M.A.; Hertz, T.; Devincenzo, J.P.; Webby, R.J.; et al. Mucosal Immune Responses Predict Clinical Outcomes during Influenza Infection Independently of Age and Viral Load. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 449–462.

- Hers, J.F.P.; Masurel, N.; Mulder, J. Bacteriology and histopathology of the respiratory tract and lungs in fatal Asian influenza. Lancet 1958, 272, 1141–1143.

- Mauad, T.; Hajjar, L.A.; Callegari, G.D.; Da Silva, L.F.F.; Schout, D.; Galas, F.R.B.G.; Alves, V.A.F.; Malheiros, D.M.A.C.; Auler, J.O.C.; Ferreira, A.F.; et al. Lung Pathology in Fatal Novel Human Influenza A (H1N1) Infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 181, 72–79.

- Guarner, J.; Falcón-Escobedo, R. Comparison of the Pathology Caused by H1N1, H5N1, and H3N2 Influenza Viruses. Arch. Med. Res. 2009, 40, 655–661.

- To, K.-F.; Chan, P.K.S.; Chan, K.-F.; Lee, W.-K.; Lam, W.-Y.; Wong, K.-F.; Tang, N.L.S.; Tsang, D.N.C.; Sung, R.Y.T.; Buckley, T.A.; et al. Pathology of Fatal Human Infection Associated with Avian Influenza A H5N1 Virus. J. Med. Virol. 2001, 63, 242–246.

- Guarner, J.; Paddock, C.D.; Shieh, W.-J.; Packard, M.M.; Patel, M.; Montague, J.L.; Uyeki, T.M.; Bhat, N.; Balish, A.; Lindstrom, S.; et al. Histopathologic and Immunohistochemical Features of Fatal Influenza Virus Infection in Children during the 2003-2004 Season. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 132–140.

- Lucke, B.; Kime, E. PATHOLOGIC ANATOMY AND BACTERIOLOGY OF INFLUENZA: EPIDEMIC OF AUTUMN, 1918. Arch. Intern. Med. 1919, 24, 154–237.

- Lindsay, M.I.; Herrmann, E.C.; Morrow, G.W.; Brown, A.L. Hong Kong Influenza: Clinical, Microbiologic, and Pathologic Features in 127 Cases. JAMA 1970, 214, 1825–1832.

- The ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012, 307, 2526–2533.

- Shieh, W.-J.; Blau, D.M.; Denison, A.M.; DeLeon-Carnes, M.; Adem, P.; Bhatnagar, J.; Sumner, J.; Liu, L.; Patel, M.; Batten, B.; et al. 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1). Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 166–175.

- Avian Influenza Weekly Update Number 924. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/emergency/surveillance/avian-influenza/ai_20231203.pdf?sfvrsn=5f006f99_123 (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Peiris, J.S.M.; Yu, W.C.; Leung, C.W.; Cheung, C.Y.; Ng, W.F.; Nicholls, J.M.; Ng, T.K.; Chan, K.H.; Lai, S.T.; Lim, W.L.; et al. Re-Emergence of Fatal Human Influenza A Subtype H5N1 Disease. Lancet 2004, 363, 617–619.

- Ungchusak, K.; Auewarakul, P.; Dowell, S.F.; Kitphati, R.; Auwanit, W.; Puthavathana, P.; Uiprasertkul, M.; Boonnak, K.; Pittayawonganon, C.; Cox, N.J.; et al. Probable Person-to-Person Transmission of Avian Influenza A (H5N1). N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 333–340.

- Chotpitayasunondh, T.; Ungchusak, K.; Hanshaoworakul, W.; Chunsuthiwat, S.; Sawanpanyalert, P.; Kijphati, R.; Lochindarat, S.; Srisan, P.; Suwan, P.; Osotthanakorn, Y.; et al. Human Disease from Influenza A (H5N1), Thailand, 2004. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 201–209.

- Chan, P.K.S. Outbreak of Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infection in Hong Kong in 1997. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34 (Suppl. S2), S58–S64.

- Gu, J.; Xie, Z.; Gao, Z.; Liu, J.; Korteweg, C.; Ye, J.; Lau, L.T.; Lu, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, B.; et al. H5N1 Infection of the Respiratory Tract and beyond: A Molecular Pathology Study. Lancet 2007, 370, 1137–1145.

- Uiprasertkul, M.; Puthavathana, P.; Sangsiriwut, K.; Pooruk, P.; Srisook, K.; Peiris, M.; Nicholls, J.M.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Vanprapar, N.; Auewarakul, P. Influenza A H5N1 Replication Sites in Humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1036–1041.

- Uiprasertkul, M.; Kitphati, R.; Puthavathana, P.; Kriwong, R.; Kongchanagul, A.; Ungchusak, K.; Angkasekwinai, S.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; Srisook, K.; Vanprapar, N.; et al. Apoptosis and Pathogenesis of Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus in Humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 708–712.

- Chokephaibulkit, K.; Uiprasertkul, M.; Puthavathana, P.; Chearskul, P.; Auewarakul, P.; Dowell, S.F.; Vanprapar, N. A Child with Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2005, 24, 162–166.

- Ku, A.S.; Chan, L.T. The First Case of H5N1 Avian Influenza Infection in a Human with Complications of Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Reye’s Syndrome. J. Paediatr. Child Health 1999, 35, 207–209.

- De Jong, M.D.; Cam, B.V.; Qui, P.T.; Hien, V.M.; Thanh, T.T.; Hue, N.B.; Beld, M.; Phuong, L.T.; Khanh, T.H.; Chau, N.V.V.; et al. Fatal Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in a Child Presenting with Diarrhea Followed by Coma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 686–691.

- De Jong, M.D.; Simmons, C.P.; Thanh, T.T.; Hien, V.M.; Smith, G.J.D.; Chau, T.N.B.; Hoang, D.M.; Van Vinh Chau, N.; Khanh, T.H.; Dong, V.C.; et al. Fatal Outcome of Human Influenza A (H5N1) Is Associated with High Viral Load and Hypercytokinemia. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 1203–1207.

- Cheung, C.Y.; Poon, L.L.M.; Lau, A.S.; Luk, W.; Lau, Y.L.; Shortridge, K.F.; Gordon, S.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.M. Induction of Proinflammatory Cytokines in Human Macrophages by Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses: A Mechanism for the Unusual Severity of Human Disease? Lancet 2002, 360, 1831–1837.

- Korteweg, C.; Gu, J. Pathology, Molecular Biology, and Pathogenesis of Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Infection in Humans. Am. J. Pathol. 2008, 172, 1155–1170.

- Minodier, L.; Charrel, R.N.; Ceccaldi, P.-E.; Van der Werf, S.; Blanchon, T.; Hanslik, T.; Falchi, A. Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Influenza, Clinical Significance, and Pathophysiology of Human Influenza Viruses in Faecal Samples: What Do We Know? Virol. J. 2015, 12, 215.

- Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza; Bautista, E.; Chotpitayasunondh, T.; Gao, Z.; Harper, S.A.; Shaw, M.; Uyeki, T.M.; Zaki, S.R.; Hayden, F.G.; Hui, D.S.; et al. Clinical Aspects of Pandemic 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1708–1719.

- Tran, T.H.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen, T.D.; Luong, T.S.; Pham, P.M.; Van Vinh Chau, N.; Pham, T.S.; Vo, C.D.; Le, T.Q.M.; Ngo, T.T.; et al. Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in 10 Patients in Vietnam. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1179–1188.

- Yuen, K.; Chan, P.; Peiris, M.; Tsang, D.; Que, T.; Shortridge, K.; Cheung, P.; To, W.; Ho, E.; Sung, R.; et al. Clinical Features and Rapid Viral Diagnosis of Human Disease Associated with Avian Influenza A H5N1 Virus. Lancet 1998, 351, 467–471.

- Yu, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ding, W.; Jia, H.; Chan, J.F.-W.; To, K.K.-W.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Liang, W.; et al. Clinical, Virological, and Histopathological Manifestations of Fatal Human Infections by Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1449–1457.

- Huang, J.-B.; Li, H.-Y.; Liu, J.-F.; Lan, C.-Q.; Lin, Q.-H.; Chen, S.-X.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Wang, X.-H.; Lin, X.; Pan, J.-G.; et al. Histopathological Findings in a Critically Ill Patient with Avian Influenza A (H7N9). J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, E672–E677.

- Srivastava, B.; Błazejewska, P.; Hessmann, M.; Bruder, D.; Geffers, R.; Mauel, S.; Gruber, A.D.; Schughart, K. Host Genetic Background Strongly Influences the Response to Influenza a Virus Infections. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4857.

- Pica, N.; Iyer, A.; Ramos, I.; Bouvier, N.M.; Fernandez-Sesma, A.; García-Sastre, A.; Lowen, A.C.; Palese, P.; Steel, J. The DBA.2 Mouse Is Susceptible to Disease Following Infection with a Broad, but Limited, Range of Influenza A and B Viruses. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 12825–12829.

- Fukushi, M.; Ito, T.; Oka, T.; Kitazawa, T.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T.; Kirikae, T.; Yamashita, M.; Kudo, K. Serial Histopathological Examination of the Lungs of Mice Infected with Influenza A Virus PR8 Strain. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21207.

- Chen, J.; Fang, F.; Li, X.; Chang, H.; Chen, Z. Protection against Influenza Virus Infection in BALB/c Mice Immunized with a Single Dose of Neuraminidase-Expressing DNAs by Electroporation. Vaccine 2005, 23, 4322–4328.

- Belser, J.A.; Wadford, D.A.; Pappas, C.; Gustin, K.M.; Maines, T.R.; Pearce, M.B.; Zeng, H.; Swayne, D.E.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.; Katz, J.M.; et al. Pathogenesis of Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) and Triple-Reassortant Swine Influenza A (H1) Viruses in Mice. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4194–4203.

- Maines, T.R.; Jayaraman, A.; Belser, J.A.; Wadford, D.A.; Pappas, C.; Zeng, H.; Gustin, K.M.; Pearce, M.B.; Viswanathan, K.; Shriver, Z.H.; et al. Transmission and Pathogenesis of Swine-Origin 2009 A(H1N1) Influenza Viruses in Ferrets and Mice. Science 2009, 325, 484–487.

- Manicassamy, B.; Medina, R.A.; Hai, R.; Tsibane, T.; Stertz, S.; Nistal-Villán, E.; Palese, P.; Basler, C.F.; García-Sastre, A. Protection of Mice against Lethal Challenge with 2009 H1N1 Influenza A Virus by 1918-like and Classical Swine H1N1 Based Vaccines. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000745.

- Groves, H.T.; McDonald, J.U.; Langat, P.; Kinnear, E.; Kellam, P.; McCauley, J.; Ellis, J.; Thompson, C.; Elderfield, R.; Parker, L.; et al. Mouse Models of Influenza Infection with Circulating Strains to Test Seasonal Vaccine Efficacy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 126.

- Tumpey, T.M.; Basler, C.F.; Aguilar, P.V.; Zeng, H.; Solórzano, A.; Swayne, D.E.; Cox, N.J.; Katz, J.M.; Taubenberger, J.K.; Palese, P.; et al. Characterization of the Reconstructed 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic Virus. Science 2005, 310, 77–80.

- Tumpey, T.M.; Szretter, K.J.; Van Hoeven, N.; Katz, J.M.; Kochs, G.; Haller, O.; García-Sastre, A.; Staeheli, P. The Mx1 Gene Protects Mice against the Pandemic 1918 and Highly Lethal Human H5N1 Influenza Viruses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10818–10821.

- Lu, X.; Tumpey, T.M.; Morken, T.; Zaki, S.R.; Cox, N.J.; Katz, J.M. A Mouse Model for the Evaluation of Pathogenesis and Immunity to Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses Isolated from Humans. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 5903–5911.

- Gao, P.; Watanabe, S.; Ito, T.; Goto, H.; Wells, K.; McGregor, M.; Cooley, A.J.; Kawaoka, Y. Biological Heterogeneity, Including Systemic Replication in Mice, of H5N1 Influenza A Virus Isolates from Humans in Hong Kong. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 3184–3189.

- Nishimura, H.; Itamura, S.; Iwasaki, T.; Kurata, T.; Tashiro, M. Characterization of Human Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Infection in Mice: Neuro-, Pneumo- and Adipotropic Infection. J. Gen. 2000, 81, 2503–2510.

- Gubareva, L.V.; McCullers, J.A.; Bethell, R.C.; Webster, R.G. Characterization of Influenza A/HongKong/156/97 (H5N1) Virus in a Mouse Model and Protective Effect of Zanamivir on H5N1 Infection in Mice. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 178, 1592–1596.

- Dybing, J.K.; Schultz-Cherry, S.; Swayne, D.E.; Suarez, D.L.; Perdue, M.L. Distinct Pathogenesis of Hong Kong-Origin H5N1 Viruses in Mice Compared to That of Other Highly Pathogenic H5 Avian Influenza Viruses. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 1443–1450.

- Tanaka, H.; Park, C.-H.; Ninomiya, A.; Ozaki, H.; Takada, A.; Umemura, T.; Kida, H. Neurotropism of the 1997 Hong Kong H5N1 Influenza Virus in Mice. Vet. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 1–13.

- Boon, A.C.M.; Finkelstein, D.; Zheng, M.; Liao, G.; Allard, J.; Klumpp, K.; Webster, R.; Peltz, G.; Webby, R.J. H5N1 Influenza Virus Pathogenesis in Genetically Diverse Mice Is Mediated at the Level of Viral Load. mBio 2011, 2, e00171-11.

- Zhao, G.; Liu, C.; Kou, Z.; Gao, T.; Pan, T.; Wu, X.; Yu, H.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Du, L.; et al. Differences in the Pathogenicity and Inflammatory Responses Induced by Avian Influenza A/H7N9 Virus Infection in BALB/c and C57BL/6 Mouse Models. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92987.

- Mok, C.K.P.; Lee, H.H.Y.; Chan, M.C.W.; Sia, S.F.; Lestra, M.; Nicholls, J.M.; Zhu, H.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.M.S. Pathogenicity of the Novel A/H7N9 Influenza Virus in Mice. mBio 2013, 4, e00362-13.

- Belser, J.A.; Gustin, K.M.; Pearce, M.B.; Maines, T.R.; Zeng, H.; Pappas, C.; Sun, X.; Carney, P.J.; Villanueva, J.M.; Stevens, J.; et al. Pathogenesis and Transmission of Avian Influenza A (H7N9) Virus in Ferrets and Mice. Nature 2013, 501, 556–559.

- Meliopoulos, V.A.; Karlsson, E.A.; Kercher, L.; Cline, T.; Freiden, P.; Duan, S.; Vogel, P.; Webby, R.J.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, M.; et al. Human H7N9 and H5N1 Influenza Viruses Differ in Induction of Cytokines and Tissue Tropism. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 12982–12991.

- Lee, Y.-N.; Lee, D.-H.; Cheon, S.-H.; Park, Y.-R.; Baek, Y.-G.; Si, Y.-J.; Kye, S.-J.; Lee, E.-K.; Heo, G.-B.; Bae, Y.-C.; et al. Genetic Characteristics and Pathogenesis of H5 Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses from Wild Birds and Domestic Ducks in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12151.

- Belser, J.A.; Lu, X.; Maines, T.R.; Smith, C.; Li, Y.; Donis, R.O.; Katz, J.M.; Tumpey, T.M. Pathogenesis of Avian Influenza (H7) Virus Infection in Mice and Ferrets: Enhanced Virulence of Eurasian H7N7 Viruses Isolated from Humans. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 11139–11147.

- Driskell, E.A.; Jones, C.A.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Howerth, E.W.; Tompkins, S.M. Avian Influenza Virus Isolates from Wild Birds Replicate and Cause Disease in a Mouse Model of Infection. Virology 2010, 399, 280–289.

- Gillim-Ross, L.; Santos, C.; Chen, Z.; Aspelund, A.; Yang, C.-F.; Ye, D.; Jin, H.; Kemble, G.; Subbarao, K. Avian Influenza H6 Viruses Productively Infect and Cause Illness in Mice and Ferrets. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10854–10863.

- Joseph, T.; McAuliffe, J.; Lu, B.; Jin, H.; Kemble, G.; Subbarao, K. Evaluation of Replication and Pathogenicity of Avian Influenza a H7 Subtype Viruses in a Mouse Model. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10558–10566.

- Heath, A.W.; Addison, C.; Ali, M.; Teale, D.; Potter, C.W. In Vivo and in Vitro Hamster Models in the Assessment of Virulence of Recombinant Influenza Viruses. Antiviral Res. 1983, 3, 241–252.

- Ali, M.J.; Teh, C.Z.; Jennings, R.; Potter, C.W. Transmissibility of Influenza Viruses in Hamsters. Arch. Virol. 1982, 72, 187–197.

- Jennings, R.; Denton, M.D.; Potter, C.W. The Hamster as an Experimental Animal for the Study of Influenza. I. The Role of Antibody in Protection. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1976, 162, 217–226.

- Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Nakajima, N.; Ichiko, Y.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Noda, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Syrian Hamster as an Animal Model for the Study of Human Influenza Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01693-17.

- Paterson, J.; Ryan, K.A.; Morley, D.; Jones, N.J.; Yeates, P.; Hall, Y.; Whittaker, C.J.; Salguero, F.J.; Marriott, A.C. Infection with Seasonal H1N1 Influenza Results in Comparable Disease Kinetics and Host Immune Responses in Ferrets and Golden Syrian Hamsters. Pathogens 2023, 12, 668.

- Zhang, A.J.; Lee, A.C.-Y.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Liu, F.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Chu, H.; Lau, S.-Y.; Wang, P.; Chan, C.C.-S.; et al. Coinfection by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 and Influenza A(H1N1)Pdm09 Virus Enhances the Severity of Pneumonia in Golden Syrian Hamsters. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, e978–e992.

- Kim, H.K.; Kang, J.-A.; Lyoo, K.-S.; Le, T.B.; Yeo, Y.H.; Wong, S.-S.; Na, W.; Song, D.; Webby, R.J.; Zanin, M.; et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 and Influenza A Virus Co-Infection Alters Viral Tropism and Haematological Composition in Syrian Hamsters. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e3297–e3304.

- Oishi, K.; Horiuchi, S.; Minkoff, J.M.; Ten Oever, B.R. The Host Response to Influenza A Virus Interferes with SARS-CoV-2 Replication during Coinfection. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0076522.

- Shinya, K.; Makino, A.; Tanaka, H.; Hatta, M.; Watanabe, T.; Le, M.Q.; Imai, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Systemic Dissemination of H5N1 Influenza A Viruses in Ferrets and Hamsters after Direct Intragastric Inoculation. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 4673–4678.

- Pappas, C.; Yang, H.; Carney, P.J.; Pearce, M.B.; Katz, J.M.; Stevens, J.; Tumpey, T.M. Assessment of Transmission, Pathogenesis and Adaptation of H2 Subtype Influenza Viruses in Ferrets. Virology 2015, 477, 61–71.

- Huang, S.S.H.; Banner, D.; Fang, Y.; Ng, D.C.K.; Kanagasabai, T.; Kelvin, D.J.; Kelvin, A.A. Comparative Analyses of Pandemic H1N1 and Seasonal H1N1, H3N2, and Influenza B Infections Depict Distinct Clinical Pictures in Ferrets. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27512.

- Svitek, N.; Rudd, P.A.; Obojes, K.; Pillet, S.; Von Messling, V. Severe Seasonal Influenza in Ferrets Correlates with Reduced Interferon and Increased IL-6 Induction. Virology 2008, 376, 53–59.

- Munster, V.J.; De Wit, E.; Van den Brand, J.M.A.; Herfst, S.; Schrauwen, E.J.A.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Van de Vijver, D.; Boucher, C.A.; Koopmans, M.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; et al. Pathogenesis and Transmission of Swine-Origin 2009 A(H1N1) Influenza Virus in Ferrets. Science 2009, 325, 481–483.

- Van den Brand, J.M.A.; Stittelaar, K.J.; Van Amerongen, G.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Simon, J.; De Wit, E.; Munster, V.; Bestebroer, T.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Kuiken, T.; et al. Severity of Pneumonia Due to New H1N1 Influenza Virus in Ferrets Is Intermediate between That Due to Seasonal H1N1 Virus and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 993–999.

- Van den Brand, J.M.A.; Stittelaar, K.J.; Van Amerongen, G.; Reperant, L.; De Waal, L.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Kuiken, T. Comparison of Temporal and Spatial Dynamics of Seasonal H3N2, Pandemic H1N1 and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus Infections in Ferrets. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42343.

- Tumpey, T.M.; Maines, T.R.; Van Hoeven, N.; Glaser, L.; Solórzano, A.; Pappas, C.; Cox, N.J.; Swayne, D.E.; Palese, P.; Katz, J.M.; et al. A Two-Amino Acid Change in the Hemagglutinin of the 1918 Influenza Virus Abolishes Transmission. Science 2007, 315, 655–659.

- De Wit, E.; Siegers, J.Y.; Cronin, J.M.; Weatherman, S.; Van den Brand, J.M.; Leijten, L.M.; Van Run, P.; Begeman, L.; Van den Ham, H.-J.; Andeweg, A.C.; et al. 1918 H1N1 Influenza Virus Replicates and Induces Proinflammatory Cytokine Responses in Extrarespiratory Tissues of Ferrets. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1237–1246.

- Watanabe, T.; Watanabe, S.; Shinya, K.; Kim, J.H.; Hatta, M.; Kawaoka, Y. Viral RNA Polymerase Complex Promotes Optimal Growth of 1918 Virus in the Lower Respiratory Tract of Ferrets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 588–592.

- Maines, T.R.; Chen, L.-M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Chen, H.; Rowe, T.; Ortin, J.; Falcón, A.; Hien, N.T.; Mai, L.Q.; Sedyaningsih, E.R.; et al. Lack of Transmission of H5N1 Avian–Human Reassortant Influenza Viruses in a Ferret Model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12121–12126.

- Imai, M.; Watanabe, T.; Kiso, M.; Nakajima, N.; Yamayoshi, S.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Hatta, M.; Yamada, S.; Ito, M.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; et al. A Highly Pathogenic Avian H7N9 Influenza Virus Isolated from A Human Is Lethal in Some Ferrets Infected via Respiratory Droplets. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 615–626.e8.

- Pearce, M.B.; Pappas, C.; Gustin, K.M.; Davis, C.T.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.J.; Swayne, D.E.; Maines, T.R.; Belser, J.A.; Tumpey, T.M. Enhanced Virulence of Clade 2.3.2.1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A H5N1 Viruses in Ferrets. Virology 2017, 502, 114–122.

- Zitzow, L.A.; Rowe, T.; Morken, T.; Shieh, W.-J.; Zaki, S.; Katz, J.M. Pathogenesis of Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses in Ferrets. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 4420–4429.

- Richard, M.; Schrauwen, E.J.A.; De Graaf, M.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Spronken, M.I.J.; Van Boheemen, S.; De Meulder, D.; Lexmond, P.; Linster, M.; Herfst, S.; et al. Limited Airborne Transmission of H7N9 Influenza A Virus between Ferrets. Nature 2013, 501, 560–563.

- Belser, J.A.; Pulit-Penaloza, J.A.; Sun, X.; Brock, N.; Pappas, C.; Creager, H.M.; Zeng, H.; Tumpey, T.M.; Maines, T.R. A Novel A(H7N2) Influenza Virus Isolated from a Veterinarian Caring for Cats in a New York City Animal Shelter Causes Mild Disease and Transmits Poorly in the Ferret Model. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00672-17.

- Kobayashi, S.D.; Olsen, R.J.; LaCasse, R.A.; Safronetz, D.; Ashraf, M.; Porter, A.R.; Braughton, K.R.; Feldmann, F.; Clifton, D.R.; Kash, J.C.; et al. Seasonal H3N2 Influenza A Virus Fails to Enhance Staphylococcus Aureus Co-Infection in a Non-Human Primate Respiratory Tract Infection Model. Virulence 2013, 4, 707–715.

- Kobasa, D.; Jones, S.M.; Shinya, K.; Kash, J.C.; Copps, J.; Ebihara, H.; Hatta, Y.; Hyun Kim, J.; Halfmann, P.; Hatta, M.; et al. Aberrant Innate Immune Response in Lethal Infection of Macaques with the 1918 Influenza Virus. Nature 2007, 445, 319–323.

- Skinner, J.A.; Zurawski, S.M.; Sugimoto, C.; Vinet-Oliphant, H.; Vinod, P.; Xue, Y.; Russell-Lodrigue, K.; Albrecht, R.A.; García-Sastre, A.; Salazar, A.M.; et al. Immunologic Characterization of a Rhesus Macaque H1N1 Challenge Model for Candidate Influenza Virus Vaccine Assessment. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. CVI 2014, 21, 1668–1680.

- Josset, L.; Engelmann, F.; Haberthur, K.; Kelly, S.; Park, B.; Kawoaka, Y.; García-Sastre, A.; Katze, M.G.; Messaoudi, I. Increased Viral Loads and Exacerbated Innate Host Responses in Aged Macaques Infected with the 2009 Pandemic H1N1 Influenza A Virus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 11115–11127.

- Marriott, A.C.; Dennis, M.; Kane, J.A.; Gooch, K.E.; Hatch, G.; Sharpe, S.; Prevosto, C.; Leeming, G.; Zekeng, E.-G.; Staples, K.J.; et al. Influenza A Virus Challenge Models in Cynomolgus Macaques Using the Authentic Inhaled Aerosol and Intra-Nasal Routes of Infection. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157887.

- Safronetz, D.; Rockx, B.; Feldmann, F.; Belisle, S.E.; Palermo, R.E.; Brining, D.; Gardner, D.; Proll, S.C.; Marzi, A.; Tsuda, Y.; et al. Pandemic Swine-Origin H1N1 Influenza A Virus Isolates Show Heterogeneous Virulence in Macaques. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1214–1223.

- Moncla, L.H.; Ross, T.M.; Dinis, J.M.; Weinfurter, J.T.; Mortimer, T.D.; Schultz-Darken, N.; Brunner, K.; Capuano, S.V., III; Boettcher, C.; Post, J.; et al. A Novel Nonhuman Primate Model for Influenza Transmission. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78750.

- Mooij, P.; Koopman, G.; Mortier, D.; Van Heteren, M.; Oostermeijer, H.; Fagrouch, Z.; De Laat, R.; Kobinger, G.; Li, Y.; Remarque, E.J.; et al. Pandemic Swine-Origin H1N1 Influenza Virus Replicates to Higher Levels and Induces More Fever and Acute Inflammatory Cytokines in Cynomolgus versus Rhesus Monkeys and Can Replicate in Common Marmosets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126132.

- Cillóniz, C.; Shinya, K.; Peng, X.; Korth, M.J.; Proll, S.C.; Aicher, L.D.; Carter, V.S.; Chang, J.H.; Kobasa, D.; Feldmann, F.; et al. Lethal Influenza Virus Infection in Macaques Is Associated with Early Dysregulation of Inflammatory Related Genes. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000604.

- Feldmann, F.; Kobasa, D.; Embury-Hyatt, C.; Grolla, A.; Taylor, T.; Kiso, M.; Kakugawa, S.; Gren, J.; Jones, S.M.; Kawaoka, Y.; et al. Oseltamivir Is Effective against 1918 Influenza Virus Infection of Macaques but Vulnerable to Escape. mBio 2019, 10, e02059-19.

- Baskin, C.R.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; Tumpey, T.M.; Sabourin, P.J.; Long, J.P.; García-Sastre, A.; Tolnay, A.-E.; Albrecht, R.; Pyles, J.A.; Olson, P.H.; et al. Early and Sustained Innate Immune Response Defines Pathology and Death in Nonhuman Primates Infected by Highly Pathogenic Influenza Virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3455–3460.

- Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Kuiken, T.; Van Amerongen, G.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Fouchier, R.A.; Osterhaus, A.D. Pathogenesis of Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Infection in a Primate Model. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 6687–6691.

- Kuiken, T.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Van Amerongen, G.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. Pathology of Human Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Infection in Cynomolgus Macaques (Macaca Fascicularis). Vet. Pathol. 2003, 40, 304–310.

More