Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Ewelina Ewa Książek and Version 2 by Fanny Huang.

Citric acid finds broad applications in various industrial sectors, such as the pharmaceutical, food, chemical, and cosmetic industries. The bioproduction of citric acid uses various microorganisms, but the most commonly employed ones are filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus niger and yeast Yarrowia lipolytica.

- citric acid

- food additives

- acidity regulator

1. Introduction

Citric acid (CA), also known as 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid, is found in plant and animal tissues such as blood, bone, and muscle. For living organisms, citric acid is one of the essential carboxylic acids in the Krebs cycle, a series of reactions that oxidize glucose into carbon dioxide and water, releasing energy. Due to its harmless nature and chelating and sequestering properties for metal ions, citric acid has applications in the food, pharmaceutical, chemical, and even metallurgical industries [1][2][1,2]. The annual global production of citric acid currently reaches approximately 2.8 million tons, and the citric acid market is one of the fastest-growing segments in the food additive industry [3]. The continuous growth in citric acid production is attributed to its wide-ranging applications, not only in the food and pharmaceutical industries but also in biopolymer production, environmental protection, and biomedicine [4][5][4,5].

In industrial citric acid production, the dominant method is submerged fermentation involving strains of Aspergillus niger, yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, and some bacterial strains [6]. Aspergillus niger is considered the best among microorganisms in the commercial synthesis of citric acid due to its high production efficiency [7][8][7,8]. The development of citric acid production has significantly increased since the last century, thanks to biotechnology, which provides knowledge about fermentation techniques and product recovery; biochemistry, which provides insights into various factors influencing citric acid synthesis and inhibition; and molecular regulatory mechanisms and strategies to enhance citric acid production efficiency [1][9][1,9].

2. Physical and Chemical Properties

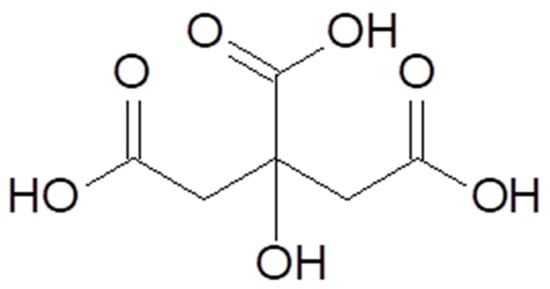

Citric acid [77–92–2], according to IUPAC nomenclature (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry), is also known as 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid. Citric acid is a polyprotic α-hydroxy acid but can also be classified as a β-hydroxy acid (Figure 1) [8][10][8,10]. It is present in plants, animal cells, and physiological fluids. In small quantities, citric acid is found in citrus fruits, especially lemons and limes. In amounts exceeding 1% of the dry weight of the product, it is present in lemons (4–8%), blackberries (1.5–3.0%), grapefruits (1.2–2.1%), as well as oranges, raspberries, and strawberries in the range of 0.6–1.3% [11][12][13][11,12,13].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of citric acid.

Citric acid is an organic compound, a tricarboxylic hydroxy acid, with three carboxylic functional groups. It is a triprotic compound that undergoes three constant dissociations, which allows it to form three types of salts and exhibit buffering properties. The chemical and physical properties of citric acid are presented in Table 1 [14][15][14,15]. Citric acid forms crystalline mono-, di-, and tri-basic salts with various cations. From a technological perspective, the most important are calcium citrate, potassium citrate, and sodium citrate [16].

Citric acid is a weak acid in two crystalline forms: Anhydrous citric acid (C6H8O7) and monohydrated citric acid (C6H8O7·H2O). Anhydrous citric acid crystallizes from a hot concentrated solution above 36.6 °C, forming a white crystalline powder. On the other hand, monohydrated citric acid crystallizes from a cold solution at temperatures below 36.6 °C, forming colorless, transparent crystals [16][17][16,17]. Anhydrous citric acid absorbs a small amount of water at 25 °C and relative humidity in the 25 to 50% range. If the humidity is between 50% and 75%, it absorbs water significantly, while approaching 75% relative humidity takes the form of a monohydrate. The anhydrous form of citric acid is obtained when the relative humidity is less than 40%. Monohydrated citric acid slightly absorbs moisture at a relative humidity of 65–75% [17].

Citric acid is highly soluble in water and organic solvents such as ethanol, 2-propanol, ether, ethyl acetate, 1.4-dioxane, tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile, and ethanol-water mixtures [18]. It has a higher solubility in alcohol than in water. Adding alcohol to an aqueous solution significantly increases the solubility of citric acid [19][20][19,20]. The solubility of citric acid in different solvents can be ranked as follows: Tetrahydrofuran < 1.4-dioxane < water < 2-propanol < ethanol < acetonitrile [21]. Citric acid does not dissolve in chloroform, toluene, benzene, carbon disulfide, or tetrachloride [17]. Its solubility increases with an increasing temperature of 20.55–60.05 °C [19][20][21][19,20,21].

When heated to 150 °C, citric acid remains stable, losing only its crystalline water. Above 175 °C, it undergoes a melting and decomposition process. Dehydration of citric acid leads to the formation of trans-aconitic acid. It is assumed that further thermal transformations of trans-aconitic acid due to dehydration result in the production of aconitic anhydride or a mixture of both isomers [15][22][15,22].

Citric acid can chelate metal ions by forming bonds between the metal, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups of the citric acid molecule. Citric acid and its salts form complexes with copper, nickel, iron, magnesium, zinc, and tin. This valuable property helps prevent changes in chemical potential, precipitation of solids, or changes in chemical properties [15][23][15,23].

Citric acid esterifies with alcohols under typical conditions in the presence of catalysts such as sulfuric acid, p-toluenesulfonic acid, or ion-exchange resin. The esterification reaction of citric acid with alcohols, occurring at temperatures above 150 °C, does not require the presence of a catalyst. Citric acid forms polyesters with polyalcohols such as sorbitol and mannitol. Interrupting the esterification reaction before completion results in the formation of free carboxylic groups, forming salts [15].

Table 1.

Chemical and physical properties of citric acid.

| Properties | Characteristic | References |

|---|---|---|

| Molar mass | Anhydrous: 192.12 g∙mol−1 Monohydrate: 210.14 g∙mol−1 |

[11] |

| Appearance and form | powdery, colorless transparent crystals or white, granular, fine powder Anhydrous: monoclinic holohedral crystals. Monohydrate: rhombic crystals |

[14] |

| Melting point | Anhydrous: 153° C Monohydrate: ≈100 °C |

[8] |

| Boiling point | None, decomposition into water and CO2 > 175 °C | [24] |

| Vapor pressure | 1.7 × 10−8 mmHg at 25 °C | [18] |

| Density | Anhydrous: 1.665 g∙cm−3 at 20 °C Monohydrate: 1.542 g∙cm−3 at 20 °C |

[14] |

| Octanol/water partition coefficient | logPOW = −1.72 ± 0.4 at 20 °C | [10] |

| Partition coefficient | logP = −1.198 ± 0.4 w 25 °C | [14] |

| dissociation constant | pK1 = 3.128 pK2 = 4.761 at 25 °C pK3 = 6.396 |

[14] |

| Henry’s constant | KH = 2.3 ×·10−7 Pam3∙mol−1 | [25] |

| Solubility |

|

[14] |

2. Application of Citric Acid in the Food Industry

From a health quality perspective, citric acid, when used as a food additive, has been approved as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives, and its Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) does not require limitation [26][54]. Derivatives of citric acid, such as calcium citrate, iron citrate, manganese citrate, potassium citrate, sodium citrate, diammonium citrate, isopropyl citrate, and stearyl citrate, have also received GRAS status as food additives [13].

Citric acid is characterized by its low production cost, easy accessibility, non-toxicity, biocompatibility, universality, and the safety of its decomposition products. It finds wide applications in the food, pharmaceutical, biomedical, chemical, agricultural, and environmental protection industries [27][92]. In food products, citric acid serves various functions, including acidity regulation, preservation, antioxidant properties, emulsification, flavor and aroma enhancement, buffering, and antibacterial activity. Citric acid’s ability to chelate metal ions and its buffering properties, when combined with citrates, make it an ideal additive in food and nutraceutical production [28][29][30][42,192,193].

Citric acid plays a significant role as an antioxidant in oil production and in limiting the oxidation of lipids in meat processing. It inhibits lipid oxidation by forming bonds between pro-oxidative metal ions and the carboxyl or hydroxyl groups of the acid. The antioxidant activity of citric acid in food depends on the dose applied and increases with higher acid concentrations [31][194].

In meat processing, citric acid reduces the pink color and increases the brightness of heat-treated meat. In cooked meat, citric acid limits the endogenous pink color and the color induced by sodium nitrite and nicotinamide. Reduction of the pink color in meat may also result from the chelation of heme iron by citric acid, preventing heme from binding with ligands that cause a pink color [32][33][195,196].

Citric acid and its salts are widely used in the food industry to prevent enzymatic browning [34][198]. Enzymatic browning of fruits and vegetables is a phenomenon that reduces shelf life and influences consumer decisions [35][36][199,200].

Citric acid is used as an additive in rinse water before deep freezing and in fruit syrups [37][201]. Adding citric acid to stored fruits and vegetables positively affects color retention and organoleptic quality and extends their shelf life. It can also be combined with other anti-browning agents, such as ascorbic acid [38][202].

The inhibition of citric acid’s polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity is due to its pH-lowering capacity. PPO activity gradually decreases with increasing citric acid concentrations. However, the citric acid concentration needed to inhibit PPO activity varies depending on the PPO activity and buffer solutions used [34][198]. Radish slices immersed in a 0.3% aqueous citric acid solution showed no browning during storage. Querioz et al. found that a citric acid concentration of 100 mM inhibited the PPO activity of cashew apples [35][199]. However, a 10 mM citric acid solution inhibited banana PPO [39][148].

Citric acid also contributes to a decrease in the thermodynamic parameters of polyphenol oxidase. This is believed to be due to a reduction in the stability of PPO and the number of non-covalent bonds in the enzyme’s structure, leading to changes in the protein’s secondary and tertiary structure [34][198].

Citric acid can be considered a substance capable of controlling cellular respiration and contributing to the better preservation of fruits and vegetables during storage [36][40][200,203].

2.1. Newly Emerging Applications of Citric Acid

Research into new applications of citric acid in various industries is currently the subject of many studies [41][42][43][44][45][46][211,212,213,214,215,216]. One of the new applications of citric acid is the production of household detergents. Citric acid chelates Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions responsible for water hardness and does not contribute to the eutrophication of aquatic systems, unlike phosphates used in detergents [47][217]. New and innovative applications of citric acid in the food industry and beyond are expected to lead to increased production.

2.1.1. Cross-linking Agent and Plasticizer

Citric acid can successfully be used in the process of cross-linking proteins [48][218], polysaccharides [49][219], and hydroxyapatite [50][220]. A breakthrough in using citric acid as a cross-linking agent came with the discovery by Rothenberg and Alberts from the University of Amsterdam. They demonstrated that glycerol and citric acid can polymerize, creating a water-soluble, biodegradable, and thermosetting resin. The combination of citric acid and glycerol at temperatures above 100 °C and below 130 °C under normal conditions leads to the formation of polyester resins through the Fischer esterification reaction [51][221].

The use of citric acid as a compatibilizer for various polysaccharides, including starch, thermoplastic starch, cotton, chitosan, and cellulose, is justified by its multi-carboxyl structure [52][222]. This allows it to be used as a cross-linking agent, plasticizer, and hydrolyzing agent [53][223].

The mechanism of the cross-linking reaction is based on the well-known Fischer esterification reaction between the carboxyl groups of citric acid and the hydroxyl groups of starch [54][224]. Citric acid can react with all three hydroxyl groups of starch. Esterification between starch and citric acid leads to mono-, di-, and tri-esters forming. Esterification primarily occurs within the branching points of amylopectin [55][225]. The formation of ester bonds can be catalyzed by reducing the pH or adding Lewis acids, which are chemical compounds capable of accepting an electron pair from a base [54][224]. In many previous studies on starch cross-linking, temperatures above 100 °C have initiated the cross-linking process [56][226]. Heating citric acid causes dehydration and the formation of an anhydride, which can react with starch to form starch citrate. With further heating, the citrate undergoes dehydration, and cross-linking can occur [57][58][227,228].

It is possible to conduct cross-linking reactions at lower temperatures (around 70 °C) using higher concentrations of citric acid. However, the efficiency of the reaction under these conditions is low because only a tiny amount of added citric acid participates in the cross-linking reaction. Furthermore, citric acid that has not reacted can act as a plasticizer [55][225]. As a plasticizer, citric acid increases the tensile strength of starch films. The improvement in tensile strength is more significant than when glycerol is used as a plasticizer [59][229]. Excessive citric acid concentration does not interact with starch molecules but can react with water, disrupting hydrogen bonds and reducing the matrix’s cohesion. This results in increased water solubility, susceptibility to deformation, and reduced thermal resistance [60][153].

FTIR spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction of starch films with citric acid have shown that citric acid can effectively inhibit starch recrystallization or retrogradation due to strong hydrogen bonding between starch and citric acid [54][224]. Additionally, citric acid-cross-linked starch films exhibit significantly higher tensile strength, up to 150% more than non-cross-linked films. However, achieving the appropriate increase in material strength requires an optimal amount of citric acid [61][230]. Citric acid concentrations below 5% act as a cross-linking agent and enhance the tensile strength of starch films. When the concentration increases from 5% to 30%, tensile strength decreases, but flexibility and material adhesiveness increase. This suggests that excess free citric acid is a plasticizer [62][231].

The main disadvantage of citric acid as a cross-linking and plasticizing agent in starch barrier films is starch degradation due to acid hydrolysis. Acid hydrolysis of starch glycosidic bonds involves the cleavage of these bonds, resulting in the protonation of oxygen and the addition of a water molecule, leading to the formation of a reducing sugar group. Effectively preventing starch hydrolysis during cross-linking in the presence of citric acid can be achieved by maintaining a pH of 4 or lower and a temperature below 105 °C [54][224].

As a cross-linking agent, citric acid strengthens bonds by incorporating covalent bonds that complement intermolecular hydrogen bonds, improving the resistance of starch films to moisture. Strong hydrogen bonds between the carboxyl groups of citric acid and the hydroxyl groups of starch result in improved interactions between molecules and reduced solubility of the films in water [60][153].

When citric acid is added in the range of 1% to 10% to thermoplastic starch, it significantly reduces water vapor permeability. This effect is due to replacing hydrophilic groups with hydrophobic ester groups that impede the diffusion of water vapor molecules through the matrix. However, water vapor permeability increases when the citric acid concentration exceeds 10%. This can be attributed to the plasticizing effect caused by an excess of citric acid. Increased citric acid concentration leads to enhanced chain mobility and increased interchain spaces, resulting from the attachment of free citric acid to the polymer chain. As a result, the water vapor diffusion coefficient increases, accelerating water vapor penetration through the starch films [63][64][65][232,233,234].

Starch films cross-linked with citric acid have higher thermal resistance [56][226]. The reason for this is that the cross-links are responsible for the resistance of cross-linked films. Cross-linked starch films exhibit significantly improved thermal resistance at temperatures above 320 °C [61][230].

The three carboxyl groups and one hydroxyl group in citric acid also allow it to cross-link glycerol, cellulose, and sebacic acid through condensation reactions, forming ester copolymers capable of drug delivery [8]. Gentamicin incorporated into the polymer effectively kills bacteria. Citric acid delivers ketoconazole as a cross-linking agent for beta-cyclodextrins on hydrogel hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC) membranes. The formation of drug-cyclodextrin complexes contributes to increased solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs [66][235].

2.1.2. Citric Acid in the Synthesis of Deep Eutectic Solvents

Deep eutectic solvents (DES) are homogeneous mixtures of two or more components capable of interacting with each other as a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and a hydrogen bond donor (HBD). Deep eutectic solvent mixtures are formed by mixing two or more components in the appropriate molar ratio in the presence of heat. Additionally, this process does not require an additional purification step [67][68][236,237]. Deep eutectic solvents are one of the most promising discoveries in “green chemistry”. They can serve as an alternative to conventional organic solvents and have numerous advantages, such as renewability, reusability, biodegradability, non-toxicity, widespread availability, shallow vapor pressure, low flammability, and ease of preparation. Moreover, the components that produce deep eutectic solvents are inexpensive and safe [69][70][238,239].

Deep eutectic solvents have been divided into four types depending on their composition. Types I, II, and IV contain metal salts and are considered toxic and less sustainable than type III deep eutectic solvents. Type III deep eutectic solvents are synthesized from readily biodegradable and regenerable raw materials such as feed additive (choline chloride, ChCl), fertilizer (urea), antifreeze (ethylene glycol), sweetener (glycerol), and plant metabolites (sugars, sugar alcohols, and organic acids) [71][240]. The most frequently studied eutectics in the literature are type III, based on the combination of quaternary ammonium salts and a compound serving as a hydrogen bond donor. Type III is the most commonly used deep eutectic solvent due to the strong interaction of hydrogen bonds between the hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and the hydrogen bond donor (HBD). Many compounds have been successfully utilized to create deep eutectic solvents. HBAs are mainly quaternary ammonium or phosphonium salts, while HBDs are most commonly amides, alcohols, and carboxylic acids. Citric acid is one of the most commonly employed HBDs among carboxylic acids [68][237]. The most popular systems for producing deep eutectic solvents using choline chloride and citric acid are 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1 [72][73][241,242]. The presence of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups allows for the formation of sufficiently strong hydrogen bonds. Deep eutectic solvents based on choline chloride and carboxylic acids demonstrate greater extraction efficiency than traditional solvents such as water and ethanol [74][243].

Various molar ratios of choline chloride and citric acid monohydrate significantly influence the physicochemical properties of deep eutectic solvents. Adding citric acid monohydrate increases viscosity, surface tension, and density. Deep eutectic solvents with a higher molar ratio of choline chloride exhibit a higher melting point. Citric acid-based deep eutectic solvents can find broad industrial applications, particularly in extracting hydrophilic components from plant or animal materials [74][243].

In the studies conducted by Kurtulbaş et al., deep eutectic solvents were intentionally designed, incorporating a hydrogen bond donor (HBD) (glycerol and ethylene glycol) and a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) (citric acid) in a specified molar ratio (1:4) for the extraction of bioactive compounds (phenols and anthocyanins). In the current investigation, Hibiscus sabdariffa was extracted using microwave-assisted extraction (MAEX). The most effective extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa was obtained from a mixture of citric acid and ethylene glycol through microwave-assisted extraction [70][239].

Hu et al., investigated the molecular mechanisms of isoliquiritigenin extraction using deep eutectic solvents of choline chloride and citric acid. The results indicated that deep eutectic solvents exhibited higher efficiency in isoliquiritigenin extraction as an extraction solvent than ethanol with water. Additionally, the increased efficiency in isoliquiritigenin extraction was primarily attributed to the strong interaction between isoliquiritigenin and the extraction solvent and the rapid diffusion of isoliquiritigenin [68][237].

2.1.3. Antibacterial Agent

Using organic acids to control bacterial flora in food, extend shelf life, and improve the safety of plant- and animal-derived products has become a common practice in the food industry. In Europe, the legal basis for using organic acids as agents contributing to the safety of animal-derived products is Regulation 853/2004 of the European Parliament and the Council [75][76][77][244,245,246].

Citric acid effectively combats pathogenic microflora in fresh and processed pork, beef, poultry, and fresh vegetables and fruits [78][79][80][81][82][247,248,249,250,251]. Its antibacterial activity involves penetrating through the cell membranes, where the pH is higher than in the surrounding environment. The mechanism of citric acid’s antibacterial action is related to acidifying the cytoplasm, disrupting metabolic processes, or accumulating the dissociated acid anion to a toxic level [83][84][252,253]. Organic acids are weak acids, so they do not completely dissociate in an aqueous environment, and their microbiological activity depends on the degree of dissociation and the pH of the food product. Reducing the pH increases the concentration of the acid, reduces the polarity of the molecules, improves acid diffusion through microbial cell membranes into the cells, and consequently increases antibacterial activity [84][85][253,254]. The effectiveness of organic acids also depends on the acid concentration, acid properties, temperature, exposure time, and microbial susceptibility [82][86][251,255].

Citric acid in concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 3.0% restricts the growth of bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Vibrio parahaemoliticus [75][78][80][82][244,247,249,251].

Citric acid exhibits synergistic effects when used in mixtures with other organic acids. A mixture of caprylic and citric acids significantly inhibits the growth of bacteria. The synergy between citric and caprylic acids is associated with the loss of cell membrane integrity and changes in its permeability. The mechanism of the synergistic action of both acids involves damaging or destabilizing the cell membrane, leading to increased permeability and, consequently, cell death. Damage to the bacterial membrane allows hydrogen ions to penetrate, resulting in a strong bactericidal effect [79][87][88][248,256,257].

Combining citric acid with other decontamination methods, such as ozonation, UV-C radiation, and ultrasonication, can significantly impact the inactivation of microorganisms in fresh food [89][41].

The effectiveness of citric acid’s antibacterial action varies and depends on many factors. Citric acid exhibits optimal antibacterial effects in a low pH environment, at low temperatures, and when used in high concentrations. Available literature sources report that using citric acid at concentrations above 2% may cause adverse sensory changes in food products [84][90][253,258]. The antibacterial effectiveness of citric acid also depends on the initial amount of microflora on the product’s surface. Depending on the initial bacterial count, citric acid reduces the number of microorganisms by 1 to 2 log cfu∙g−1 [75][244].

2.1.4. Deamidation of Gluten

Wheat gluten is widely used in the food industry, serving various purposes, such as emulsifiers and imparting cohesiveness and elasticity. However, its utility is limited due to its low solubility under neutral conditions. A practical method to enhance the properties of gluten is deamidation using carboxylic acids, including citric acid [91][92][259,260].

The deamidation reaction transforms amidic groups into carboxylic groups, mainly glutamine and asparagine residues. This transformation results in increased electrostatic repulsion, the disruption of hydrogen bonds, and the dissociation of polymers, ultimately improving the solubility of gluten. While treating gluten with citric acid, the availability of peptide bonds and hydrogen ions influences the competition between hydrolysis and deamidation. The degree of hydrolysis of deamidated gluten decreases with increased citric acid concentration and treatment time, contributing to an increase in soluble protein content after deamidation [45][93][215,261]. Deamidation by citric acid increases the solubility of gluten to around 70% at pH 7. The shift of the protein’s isoelectric point towards acidic pH confirms that deamidation increases the quantity of protein polyelectrolytes, resulting in improved solubility at neutral pH. Deamidation involves the cleavage of peptide bonds, indicating that it is primarily responsible for increasing protein solubility rather than hydrolysis [93][94][261,262].

Deamidation of gluten with citric acid significantly enhances its emulsifying, foaming, and elasticity properties. Emulsions stabilized with deamidated gluten feature smaller emulsion droplet sizes, indicating their ability to reduce surface tension. High emulsion stability results from the increased flexibility of the gliadin molecule or its molecular rearrangement [93][261]. The improvement in the foaming capacity of deamidated gluten is attributed to the increased molecule flexibility, leading to enhanced protein adsorption and anchoring at phase boundaries [95][96][263,264]. Deamidation also leads to changes in the secondary conformation of the protein, driven by increased electrostatic repulsion and a reduction in hydrogen bonds [94][262]. The secondary structure of gluten consists of 34.5% α-helices, 17.3% β-turns, and 44.8% β-sheets. Deamidation increases α-helices and β-turns while reducing β-sheets [92][95][260,263].

Citric acid exhibits a solid capability to break peptide bonds in gluten, which leads to a transformation in the tertiary structure of the protein. Protein fractions of gluten with a higher molecular weight are more susceptible to degradation than those with a lower molecular weight. After deamidation with citric acid, the presence of sulfhydryl groups in gluten has been confirmed, while the tertiary structure becomes less compact [95][96][263,264].

Deamidation with citric acid can contribute to the improvement of the nutritional properties of gluten. From a nutritional standpoint, gluten is not considered a good protein source due to its deficiency in lysine and threonine. Deamidation with citric acid increases the overall quantity of essential amino acids, including lysine [93][261].

2.1.5. Extractant

Citric acid can be an effective pectin extractor from fruit pomace instead of toxic mineral acids such as sulfuric or nitric acid. Pectin extraction using citric acid can reduce waste from fruit and vegetable processing and limit the harmful environmental impact of wastewater from conventional extraction methods [97][98][265,266].

The process of pectin extraction typically occurs at around 97 °C with a pH of 2.5 using water acidified with citric acid [30][97][193,265].

Extracting pectin from citrus fruit peels using citric acid allows for obtaining pectins with a high galacturonic acid content, essential for their application as a gelling agent. Pectins also have a high molecular weight, indicating a high content of neutral sugars. The viscosity of the extracted pectins increases with a higher concentration of citric acid. Although the extraction process may yield lower efficiency than traditional methods, it results in pectins of high purity [99][267].

The pectins extracted from cocoa husks were characterized by a high degree of acetylation, contained rhamnogalacturonan, and had side chains rich in galactose. Despite their high degree of acetylation, these pectins formed gels in a low pH environment and at a high glucose concentration, suggesting their potential use as an additive in acidic products [100][268].

2.1.6. Inhibition of Protein Adhesion

The issue of protein adhesion to steel surfaces poses numerous challenges in food production and processing. Proteins adhering to equipment surfaces can serve as a nutrient source for microorganisms, leading to product contamination. Removing allergens and preventing cross-contamination is a critical point in the food production process. One method to inhibit the adhesion of chicken egg white proteins to stainless steel surfaces is to use a citric acid solution [101][269].

The effect of inhibiting protein adhesion by citric acid involves changing the surface charge of steel from positive to negative in an environment with a pH of 7.4 due to the attachment of dissociated carboxyl groups from the acid. This leads to the repulsion of negatively charged protein molecules such as ovalbumin or ovomucoid [46][101][216,269].