1. Introduction

A central part of cultural heritage studies is the review of historical archives that allow us to know the observations and experiences of those who recorded scarcely explored territories in the past, especially in the context of European colonization of vast areas of the world in the seventeenth century is crucial for heritage studies. The episode of the Dutch expedition to southern Chile (1642–1643) during the colonial period marks a turning point for the Spanish Crown in South America, as it spurred the reconquest of this vast territory that the Spaniards had lost to indigenous peoples starting in 1598. So far, the academic approach to this Dutch expedition has primarily relied on Spanish translations carried out by Medina. As we will explain later with more details, Medina published a translation based on a previous English translation of the diary (1923) and he reprinted a previous one based on the Dutch original (1924). Medina was one of the leading Chilean intellectuals at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. However, the original source itself has not undergone a comprehensive study; rather, it has been cited superficially and without in-depth analysis. The lack of a thorough examination of the original source has led to the notable discrepancies among various translations going unnoticed.

Despite the importance of the travel diary in question (Journael ende historis verhael van de Reyse gedaen bij Costen de Straet Le Maire naer de Custen van Chili), which lies in the fact that it presents a significantly different panorama than that presented by Chilean historiography regarding the state of affairs in the city of Valdivia and its inhabitants during the period of this expedition, it has been insufficiently studied

[1].

2. A War between Spain and Netherlands in Chilean Lands

During the 17th century, the colonization of South America progressed within the context of the expansion of European empires worldwide. Castile and Portugal divided a significant portion of the continent

[2], while the Netherlands, France, and England made incursions to occupy strategic positions in the territory to exploit raw materials and control trade routes. In the context of the “Eighty Years’ War” between the Netherlands and the Spanish Empire, also known as the War of Flanders (1568–1648), Flanders had expanded institutionally, politically, militarily, and economically across the world through the East and West India Companies

[3,4][3][4]. It is important to remember that Flanders was part of the Habsburg patrimonial heritage, but that the revolt eventually led to the Act of Abjuration in 1581 by the Prince of Orange. The Dutch used espionage and intelligence strategies to obtain maps of the Americas held by the Portuguese and Spanish. By the early 17th century, they were present in Pernambuco (Brazil), Guyana, the Northamerican east coast, and had occupied and attacked strategic positions in the Caribbean, such as Puerto Rico (1625). As part of the Dutch-Portuguese War, an extension of the Eighty Years’ War against the Habsburgs, Dutch expeditions led by Cordes (1599), van Noort (1599), and van Spilbergen (1615) allowed them to assess the state of Spanish positions in the southern part of the Viceroyalty of Peru

[5] (pp. 4–70). Throughout this time, the Dutch developed a “particular fascination” with Chile, imagining alliances with the fierce natives against the Habsburgs

[6]. Van Noort, a merchant and pirate who led a Dutch expedition to South America between 1598 and 1601, wrote: “The brave warriors” (…) “glorious victory” (…) “the revenge for the tyranny and slavery that the Spaniards made them suffer” (…) “destroyed papist idols, saying ‘now we have put an end to the Spanish God’”. Between 1620 and 1643, the Dutch carried out three Chilean expeditions in order to establish their fleet in the Pacific, control the passage through Cape Horn

[7] and the Strait of Magellan, form alliances with the Indigenous People inhabitants of Chile or “Chileans”, and seize the gold and silver being extracted and traded through the Pacific: L’Hermite (1624), Aventroot (1626), and Brouwer (1643). However, all these attempts failed to achieve their objectives. Unlike previous Dutch expeditions, the Brouwer expedition sought to consolidate a long-lasting Dutch settlement on Chilean soil.

In this context, a Dutch fleet entered through Cape Horn in 1642 en route to Chile, the southernmost position of the Spanish Crown in America

[5] (pp. 71–88) and

[8] (pp. 124–128). When the Dutch arrived in the former Spanish city of Valdivia in 1643, this territory had been under indigenous control for 45 years. The Dutch witnessed the state of the city and its surroundings, made contact with the main indigenous leaders, and planned a colonization attempt to exploit gold mines

[6].

Father Alonso de Ovalle stated during the contemporaneous period of the expeditions: “The Dutch enemy is well aware of the quality of this river and port, and for many years, they have set their eyes on it and made efforts to obtain it”

[9] (p. 26). Brouwer (who died on the way to Valdivia and was buried there) and Herckmans (who assumed command of the expedition) managed to establish themselves in the city for a little over two months, engaging in negotiations with various caciques (indigenous chiefs) from different parts of southern Chile. The Dutch sought military alliance with the Mapuche-Huilliche against the Spaniards, the spread of Calvinism among the population that had shown an “anti-Catholic” sentiment, control of trade routes through the South Pacific, and the exploitation of the now legendary gold deposits surrounding Valdivia. Initially, the Dutch, seeing the availability of the Mapuche-Huilliche, sent one of the ships to Pernambuco, or Dutch Brazil at that moment, in search of more men and weapons to begin conquest and colonization. However, Herckmans decided to abandon the city on 28 October 1643, due to the refusal of the Mapuche-Huilliche to supply them with food and the indigenous population’s unwillingness to reveal the location of the gold deposits. De Ovalle

[9] suggests that the indigenous leaders may have adhered to the terms established in the Treaty of Quillín or Peace of Quillin, which they had signed with the Spanish in 1641. In 1645, the Marquis of Mancera once again took Valdivia with the largest Spanish royal navy ever seen in southern America. The city was occupied, its surroundings were fortified, the Mapuche-Huilliche who had negotiated with the Dutch were punished, and the indigenous population returned to Spanish subjugation through encomienda (forced labor system) and captivity.

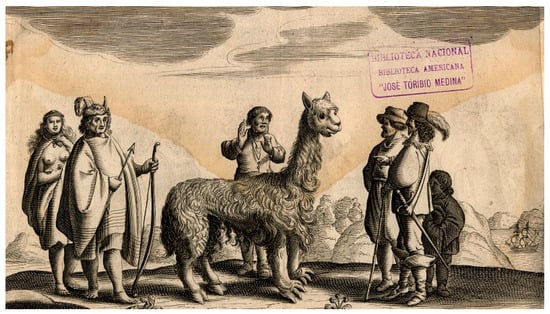

Figure 1 constitutes one of the earliest published pictorial representations of the indigenous population of Chile, and in this case, it holds significant value as it is not from a Spanish source. In this image, the way in which the indigenous people are dressed stands out (the woman is depicted with her breasts exposed), the weapons they possess, a llama, and the landscape in which they live, featuring hills and forests. Of equal importance is the llama in this figure, which is called “camel-sheep” in the Dutch and in the German texts. The relevance of this animal lies in the fact, as we will see during the analysis, that the indigenous people used it as a currency or high value exchange object with the Dutch and most certainly among themselves, too. Other documents generated during this expedition show a couple of indigenous individuals, some plants found in the area, translations of words from the Mapuche language, and maps of the cities of Castro and Valdivia (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Dutch representation of a Chilean Indian couple, members of the Brouwer expedition and a llama or chiliweke, illustrated in Journal and History. Photo: Netherlands Scheepvaartmuseum, Amsterdam. Source: Biblioteca Nacional, Biblioteca Americana José Toribio Medina (

https://www.museodeniebla.gob.cl, accessed on 31 January 2021).

Figure 2.

Overlay of the Dutch map onto a satellite image of the present-day city of Valdivia. Source of satellite image: Hugo Romero-Toledo. Source of Dutch map: Een corte Beschrijvinge vant Leven, Seden ende Manieren der Chilesen (1643).

There are at least three Spanish sources that recount the Dutch expedition to Valdivia, and that are not based on any of the versions of the Dutch’s expedition diary analyzed here. The first is by De Aguirre

[10], who notes that the Dutch expedition brought a letter from the Prince of Orange, which was presented to the indigenous chiefs, especially Manquipillian (possibly the Mapuche leader Manqueante, lord of the Mariquina valley). According to De Aguirre’s account, the Dutch promised to return the following year with ten to twelve ships and two thousand men. Additionally, the author mentions the Dutch commitment to bring five thousand weapons, ammunition, provisions for three years, clothing, and hostages to repopulate and fortify Valdivia. It is important to note the promise to bring a thousand Black men to relieve the “Indians’’ from personal service. The source of this information is four Dutch soldiers who remained in Valdivia, and the testimony of the cacique Manqueante himself given to the Spaniards

[10] (num. CII). Manqueante at this point had turned into a key ally of the Spaniards and the four Dutchmen had abandoned the expedition because of the food scarcity and can be considered prisoners. In the same chronicle, it is possible to identify an episode in which the indigenous ambassadors of Manqueante who attend negotiations with the Spaniards are armed with Dutch breastplates, swords, and steel helmets

[10] (num. CLXV).

The second source is Father Diego de Rosales

[11], written in 1674, but only published in 1878. He derives his account from a prisoner who is interrogated by a Jesuit priest. Rosales’ text confuses the Dutch with the English in some paragraphs but is clear in stating that the expedition departed from Amsterdam under the command of Henry Braut (deformation of Brouwer). According to the interrogated prisoner, the Dutch mission was to populate the city of Valdivia, and for this purpose, they brought tools, six hundred soldiers, officers, and sailors. Rosales notes Braut’s death and his replacement by Elias Erquemans (deformation of Herckmanns). Subsequently, based on a report from a Spanish soldier to the Marquess, Rosales mentions that the “English’’ had fortified Valdivia and, although they were suffering from hunger, had formed alliances with the indigenous people of Mariquina, Osorno, and Villarrica. The Dutch had promised to expel the Spaniards, recording their victory over them in Chiloé. De Rosales mentions that the Dutch stated that they were coming to aid the indigenous people and were willing to advance toward Arauco and Yumbel. Based on another letter sent to the Marquess by another Spanish soldier, it is mentioned that the Dutch sailed up a river (likely the Cruces River) to speak with Chief Manqueante. Rosales recounts that there were exchanges of goods between the indigenous people and the “English”, and the latter provided them with weapons to fight against the Spaniards. Rosales presents a letter that Elias Erquemans allegedly sent to Manqueante, stating that they were withdrawing due to lack of supplies

[11] (p. 228). In the following years, reports arrived from Dutch soldiers who had remained or had been captured, indicating that the Spaniards had occupied Valdivia, the fortification built by the Dutch, and had unearthed Captain Braut.

The third source is Alcedo y Herrera

[12], who records in his chronicle that the Dutch expedition took place in 1633, changing the name from Brouwer to Henrique Beaut. The Dutch objective was to take Valdivia, establish a colony in the South Sea, and fortify it. In their version, the Spanish governor, with a troop of garrison soldiers and the assistance of “allied Indians”, forcibly drove out the Dutch, compelling them to retreat by force

[12] (pp. 148–149).

As can be observed, the visit of “foreigners”, enemies of Spain, is mentioned in the two most significant contemporary Spanish sources about the Dutch expedition. The presence of the Dutch aroused the greatest concerns of the colonial Spanish government, which had long feared the arrival of the “European enemy” on the Chilean shores, particularly in the southern territories that indigenous groups had reconquered since 1598

[13] (p. 258). In this context, the initial Dutch and German accounts of the Dutch expedition were published, thereby rendering visible, for the first time, the existence of former Spanish territories currently under indigenous control, primed for potential conquest.

3. Colonial Narratives: Transimperial Eyes

The study of colonial narratives requires interdisciplinary work to decolonize knowledge and to evaluate the historical and cultural heritage of colonization areas. Anthropology, history, geography, literary studies, translation studies, and cultural studies, among others, have been developing systematic reflections on the production of Eurocentric discourses and material practices that narrated, imagined, and acted upon Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas, identified as “the rest of the world”, since the late 1970s

[14]. Chronicles have been incorporated into the field of travel narratives analysis

[15,16,17[15][16][17][18],

18], which opens up the opportunity to interpret the accounts of chroniclers in light of what the social sciences and humanities have developed regarding how hegemonic or dominant positions materially produce and/or discursively construct colonized territories. These colonial narratives extend beyond the temporal limits of when they were written

[19], transforming into a male, white, Christian, heterosexual, and socio-economic political project that simplifies the ontological complexities of different world

[20] into a simplified narrative of barbarism versus civilization, natural resources, or virgin lands where history is inscribed from the metropolis

[21]. Moreover, they share similarities with “patchwork quilts” as they consist of fragments from various earlier texts, expertly or less expertly arranged by the compiler.

Hulme

[22] argues that colonial narrative is a set of linguistic practices, colonial relationships, bureaucratic documents, and romanticized accounts through which the non-European world is produced. The colonial narrative is deeply related to military strategies, political orders, social reforms, mixed with memory and personal experiences, reflecting geographic, ideological, national, and religious projects. Colonial narratives justify the processes of occupying indigenous territories and the dispossession of lifeworlds, mobilizing ideas of civilization and barbarism. An important part of this discourse in the Americas is constituted by the Caribbean and cannibalism

[22], the tropics and diseases

[23], the Amazon as the Garden of Eden

[24], the remoteness and vastness of Patagonia

[25,26,27][25][26][27]. In these narratives, the physical borders of the territories are not important, but rather historically constructed entities with movable and fluid boundaries, socially constructed and materially produced from hegemonic positions.

The field of colonial narrative studies can be divided into three main groups: firstly, there is the criticism of the colonial from Marxist positions, where the concepts of discourse and ideology are strongly inspired by Gramsci and Althusser, and where the production of colonial narratives is directly related to how imperial powers are being deployed in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Perspectives belonging to this tradition include Said

[28], also influenced by Foucault, Hulme

[22], Pratt

[29], and Bhabha

[30], among others. In Pratt’s seminal work

[29], a series of concepts such as “contact zone” are mobilized to identify spaces of colonial encounters, where people who are geographically, historically, and linguistically separated enter into relationships of coercion, inequality, and conflict. Another conceptual contribution is the “anti-conquest” strategy of representation, where narrators become innocent witnesses whose imperial eyes observe the events happening around them. Pratt’s work focuses on the narratives of the 18th century and criticizes how bourgeois forms of subjectivity and power inaugurate a new territorial phase of capitalism, seeking raw materials, expanding trade, and rivaling with other European powers. More recent currents of travel narrative studies have sought to subvert colonial narratives by discrediting European versions, for example, by questioning the true quality of “discoveries” and showing how narrators have altered certain findings to fit within the European ontology

[16]. For instance, ancient society ruins are portrayed as abandoned, disregarding any potential use that the groups inhabiting the territories at the time of the narrator’s visit could have given them.

The second group of perspectives has developed in light of Derrida and Foucault, placing special emphasis on how regimes of truth and domains of knowledge have been produced. Works such as Chatwin’s “In Patagonia”

[26] and feminist studies like Mills’ “Discourses of Difference”

[31] analyze how colonial narratives have been produced by white men, soldiers, explorers, priests, or scholars who freely moved within the public sphere. These perspectives engage in textual analysis that deconstructs racial and gender colonial relationships, with a particular focus on translation studies, which involve not only translating languages but also discourses and cultures. Bassnett

[32] argues that narratives like “The Odyssey” or “The Iliad” established women as objects of desire or destinations, rather than co-travelers, and that this was further intensified with the idea of the New World associated with the search for fortune, risk, and heroic explorations. In his analysis of colonial discourse, Spurr

[19] also points out the radicalization of racial and ethnic differences, which tend to lead to inferiorization and conceive people as extensions of the landscape. The colonizer establishes their authority by demarcating identity and difference from the savage other, but this is an ongoing process. Far from being univocal, colonial discourse is ambivalent and employs different strategies to establish power relations.

The third perspective corresponds to what is known as the “decolonial turn”, which aims precisely at how oppression is based on the naturalization of the inferiorization of the voices, knowledge, and actions of the “others”. This intersectionality with processes of coloniality, understood as a fundamental part of modernity

[33[33][34],

34], implies that the “other” is conceived through the naturalization of territorial, racial, cultural, and epistemic hierarchies that enable the reproduction of domination. Together, these hierarchies constitute the “dark side” of modernity and are sustained by a pattern of colonial power through the coloniality of being, knowing, and power

[35[35][36],

36], embodying the “hybris of point zero”, meant from which Eurocentric epistemic universalisms have been posited

[33].

Besides the important decolonial approach, we have to insert this study within a specific field of the history of science and knowledge. A key element of this current is to analyze any text within its historical circumstances and not from a present point of view

[37] (p. 60). María Portuondo

[38] has shown how important the acquisition of scientific knowledge concerning the Americas was to the Spanish administration and the great care they took to keep this knowledge to themselves. Arndt Brendecke

[39] emphasizes the relevance of empirical data obtained in situ in case of the Spanish Monarchy, which lead to the famous geographic accounts, an inquiry carried out during the final quarter of the 16th century, in order to gain more specific information about the recently conquered and incorporated territories. The expedition that produced the diary was still part of what Benjamin Schmidt

[40] (p. 1) has called “the Dutch discovery of America”. America had come to the Netherlands long before, but it was at the beginning of the 17th century when the Dutch started to go there themselves

[41] (pp. 5–6).

Translations also played a decisive role in the distribution of knowledge in Early Modern time. Research on Early Modern translations has increased in the last two decades and has helped us to understand the various motivations and practices carried out around the art of translation

[41,42,43][41][42][43]. One of those practices that becomes relevant to this study is second hand translations, when one does not translate from the original, but from a translation made into another language already. For example, in Early Modern times, French versions of Spanish texts were often made from the already existing Italian translation

[44] (p. 112). Concerning the English, in those days, they rarely mastered the Dutch language and it was quite common that they translated from other languages

[45] (p. 43). It was also quite normal to alter the original within specific interests

[46] (pp. 226–238). Both those aspects will be very relevant within this study.

Following a decolonial approach we aim to unveil and contrast the colonial/imperial discourses behind the Dutch, German, English and Spanish translated versions of the source narrative because “in the transformations that occur in the translation processes, as well as in the circumstances that surround them and the personal intentions that influence them, one can understand the representations that a group forms about the familiar and the foreign”

[47] (p. 85). Through a critical reading of the source narration and a comparative reading of the previously mentioned translated versions we aim to identify the historical and cultural heritage of this territory. This critical reading consists of the identification of ethnographical representations of the Mapuche-Huilliche People and of the city of Valdivia and shifts in terms of the way in which these versions communicate these representations. Then we proceeded to link these shifts to the imperial discourses/contexts that generated the versions.