Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Lindsay Dong and Version 2 by Lindsay Dong.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is typically first diagnosed in early childhood. Medication and cognitive behavioural therapy are considered effective in treating children with ADHD, whereas these treatments appear to have some side effects and restrictions. Virtual reality (VR), therefore, has been applied to exposure therapy for mental disorders. Previous studies have adopted VR in the cognitive behavioural treatment for children with ADHD.

- attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- virtual reality

- cognitive behavioural therapy

1. Introduction

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity that interferes with cognitive and social functioning [1]. ADHD is classified into three subtypes, based primarily on the presentation of symptoms. Individuals with the inattentive subtype may have difficulty maintaining attention, organizing tasks, following instructions, and completing assignments or activities [1]. Individuals with the hyperactive–impulsive subtype may frequently fidget, squirm, or feel restless and have difficulty staying seated, engage in excessive talking, and have a strong need for movement or physical activity [2]. Individuals with the combined subtype exhibit symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity–impulsivity. This subtype often presents with a wide range of symptoms that can vary in severity [2]. Impaired social functioning can lead to inappropriate social interactions, poor peer relationships, and even peer rejection. Specific behaviours associated with social rejection among children with ADHD include aggression, explosiveness, inflexibility, control, bossiness, inattention during activities, and rule violations [2]. About 60% of children with ADHD experience peer rejection [3] because they are usually disliked in the initial social interaction [4], which results in reduction in future opportunities to practice social skills. Persistent peer rejection or social impairment is related to a significant risk for many unhealthy outcomes in adolescent development. Numerous studies have shown that social impairment is associated with depression and anxiety [5][6].

Medication (e.g., methylphenidate) is the most effective way to manage ADHD-related symptoms by increasing the activities in the brain [7]. However, once patients stop taking the medication, the symptoms return [8]. It was found that these medications have side effects, including sleep problems, loss of appetite, headaches or stomach pains [9]. As a result, some parents may not provide medication for their children with ADHD [10]. In addition to medication, cognitive behavioural therapies such as social skill interventions are one of the common and widespread approaches for improving social skills among children with ADHD [11]. According to the meta-analysis of Storebø et al. [11], the forms of social skills intervention often include roleplays, games, and exercises performed individually or in small groups. These traditional approaches can offer real-life practice opportunities in a supportive environment [12]. Specific social skills can be taught to the children based on their unique needs and preferences. Immediate feedback can be provided by the instructors to allow the children better understanding of their improvement and weaknesses [13]. Even so, these traditional training approaches possibly bring some limitations to the learning process of children with ADHD, for instance, time and space constraints, and distractions caused by the environment. These children have symptoms of inattention; face-to-face training can easily be interfered with by other factors.

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a promising tool for the rehabilitation of psychological disorders, such as ADHD, and for providing a safe and effective learning environment [14][15]. VRs create a three-dimensional environment that allows users immersion and interaction with the virtual world [16]. Although numerous VR applications for children and adolescents with ADHD have been demonstrated [15][17][18][19], these VRs are mainly used for enhancing attention, hyperactivity, impulsivity and executive functions in a safe environment. To the best of our knowledge, research on the use of VR to improve social skills in children with ADHD is limited. Yet, several studies assessed the efficacy of VR on social skills among children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability and found better performance on social skills after VR-based interventions [20][21][22]. Given the benefits of VR in creating a better learning environment and a limited amount of research on the development of VR-based social skills training for children with ADHD, it is critical to develop a VR-based social skills intervention for children with ADHD.

2. Virtual Reality Intervention for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

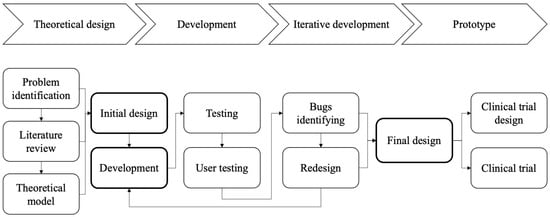

Social VR is the result of interdisciplinary collaboration among healthcare researchers, professionals, an educator, and virtual reality development engineers. The development process of Social VR is shown in Figure 1. The basic information and comparability of the descriptor of the Social VR are demonstrated in Table 1. Table 1 is a prototype table which was conceptualised and proposed by Baranowski [23] to delineate the essentials of a new game.

Figure 1. Design and development process.

Table 1. Brief description of Social VR characteristics.

| Social VR Characteristics | Description | |

|---|---|---|

[30]. These three scenarios offer a structured and predictable setting, which can be beneficial for children with ADHD who often thrive in environments with clear routines and expectations [30].

Table 2. Description of each condition.

| Condition | Target | Description | Interaction | Instant Feedback | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | |||||||

MTR |

Social interaction Attention Initiation Inhibition |

Participants take the MTR to the destinations required by the instructions. Participants are required to abide by MTR etiquette and manners during the ride. Various passengers and strangers ask the participants for help. Multiple activities take place inside the compartment, training participants’ attention, initiative, and inhibition. |

|

| |||

| Health topics | Social skills for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | ||||||

| Social interaction | Attention Initiation Inhibition |

Participants follow the instructions of the teacher and complete each task accordingly. The participants interact with the classmates and teachers. Participants encounter several incidents in the classroom and playground to train their attention, initiation, and inhibition. |

|

||||

| Avatar | |||||||

Campus |

|

Targeted age groups | |||||

Market & Restaurant |

Social interaction | Children aged 6–12 years | |||||

| Attention Inhibition Working memory |

Participants purchase some items at the market and buy takeaway food at the restaurant according to the instructions. Participants interact with the salespeople and waiters. |

|

Other targeted group characteristics | Exclusion criteria: with an IQ lower than 85; with severe physical or learning disabilities; perceived dizziness and motion sickness while using VR | |||

|

Short description of the game idea | A VR program aimed at enhancing social interaction skills and ADHD-related symptoms | |||||

|

|

Target players | Individual | ||||

| Guiding knowledge, behaviour change theory models, or conceptual frameworks | Learning theory, Barkley’s Behavioural disinhibition theory and Brown’s Model of ADHD | ||||||

| Intended health behaviour changes | Improvement in social interaction skills | ||||||

| Knowledge elements to be learned | Social skills | ||||||

| Behaviour change procedures or therapeutic procedures used | Awareness of the problems, intention to take actions, feedback on the actions, practicing the desired actions, repetition, and sustaining the desired behaviours | ||||||

| Clinical or parental support needed | Clinical support | ||||||

| Data are shared with parent or clinician | Yes | ||||||

| Type of game | Everyday life conditions | ||||||

| Story | |||||||

| Synopsis | A child has a series of tasks in Mass Transit Railway (MTR), Campus, Market and Restaurant conditions. In the MTR condition, the child needs to start from one destination to another. During their travelling, they must decide how to respond to different contingencies. In the Campus condition, they need to comply with the instruction of the teacher in the scenario. In the Market and Restaurant conditions, they need to purchase a number of items, in which they encounter different daily life interactions | ||||||

| How the story relates to targeted behaviour change | Through these scenarios, they learn to comply with rules, etiquette, manner, and properly communicate and interact with others. These improve their attention, initiative, inhibitive, emotional control, and self-control | ||||||

| Game components | |||||||

| Player’s game goals and objectives | Social interaction skills training | ||||||

| Rules | Restricted social skills training (20 min per session) | ||||||

| Game mechanics | MTR, Campus, and Market and Restaurant for social skills, social interaction, attention, initiative, inhibition, self-control and emotional control | ||||||

| Procedures to generalise or transfer outside of the game | Mainly help enhance social skills through real-life scenarios | ||||||

| Virtual environment | |||||||

| Setting | The scenarios included MTR stations, Compartment, Classroom, Playground, Market, and Restaurant | Characteristics | The scenarios contain passer-by, teachers, classmate, sales, and waiters to interact with children | ||||

| Abilities | Characters communicate and interact with the children through different events and incidents | ||||||

| Game platform(s) needed to play the game | Unity real-time development platform | ||||||

| Sensors used | Oculus Quest 2 | ||||||

| Estimated play time | 1–2 h | ||||||

The design of Social VR is theoretically driven by learning theory, Barkley’s model [24] and Brown’s model [25]. Learning theory depicts the conditions and processes during learning, providing models for developing instructions that facilitate better learning [26]. The theory explains how people understand and integrate information into mental models that generate new knowledge, what motivates people to learn and what environments promote or hinder learning [27]. Therefore, to provide appropriate training for enhancing social interaction skills in children with ADHD, the design of Social VR should consider the features of ADHD. Barkley’s model is based on the idea that the inability to inhibit is at the root of the problems experienced by people with ADHD, and inhibition is indispensable for four efficient functions, namely (1) nonverbal working memory, (2) verbal working memory, (3) self-regulation of affect/motivation/arousal, and (4) reconstitution (generativity and planning). In Brown’s model, six separate clusters were categorised to describe cognitive impairments in individuals with ADHD, including (1) activation, (2) focus, (3) effort, (4) emotion, (5) memory and (6) action. Although the emphases of these models are distinct, a comprehensive understanding of ADHD thus needs to consider the multiple factors that may contribute to ADHD-related symptoms.

In view of the inhibition behaviours and executive impairment among children with ADHD, creating a concentrated, organised and productive environment is essential in children’s learning process [28]. An immersive, realistic and interactive environment can be provided by VR to engage and motivate children to learn [29]. In this usability study, the Social VR prototype had three conditions, including (1) MTR; (2) Campus; and (3) Market and Restaurant, which cultivate children’s manners and etiquette in different circumstances. Each condition specifically focuses on social interaction skills, initiation, inhibition, self-control and emotional control (Table 2). The participants need to interact with different characteristics (e.g., passengers, teachers, classmates, sales and waiters) in the three conditions so as to complete a series of tasks. Immediate feedback is provided to indicate the correctness of the responses of the participants. Furthermore, these three conditions contain scenarios that are familiar to participants, increasing the ecological validity of the scenarios and facilitating the transfer of acquired abilities to daily life activities

Note. RA: research assistant.

The virtual reality development engineers created the scenarios using the Unity platform software based on the above requirements. The initial version of the Social VR prototype was iteratively tested to detect all bugs and areas for improvement throughout the development process. In addition to enhancing the social interaction skills of children with ADHD, the social VR is designed to prevent all discomfort and symptoms of motion sickness. Children with ADHD were recruited to collect feedback on their interactions with the prototype to validate the prototype. Modifications to the initial version were made based on suggestions for its usability, such as ease of use, authenticity, satisfaction, and adverse effects (e.g., motion sickness), from users who participated in testing the initial version. The modification included optimising the frame rate to provide smooth and fluid visuals, reducing the latency between head movement and visual updates in the VR environment and limiting the field of view changes, especially during scene transitions or when the user is moving.

The aim of Social VR was to assist children with ADHD in acquiring the knowledge and skills related to social interaction. Immersive virtual environments were utilised in the education setting to make the learning process more engaging and motivating [31]. Considering the features and intention, Social VR is defined as a gamification-based intervention [32].

References

- Biele, G.; Overgaard, K.R.; Friis, S.; Zeiner, P.; Aase, H. Cognitive, emotional, and social functioning of preschoolers with attention deficit hyperactivity problems. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 78.

- McDonald, K.L.; Wang, J.; Menzer, M.M.; Rubin, K.H.; Booth-LaForce, C. Prosocial behavior moderates the effects of aggression on young adolescents’ friendships. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2011, 5, 127–137.

- Carpenter Rich, E.; Loo, S.K.; Yang, M.; Dang, J.; Smalley, S.L. Social functioning difficulties in ADHD: Association with PDD risk. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 329–344.

- Glenn, D.E.; Michalska, K.J.; Lee, S.S. Social skills moderate the time-varying association between aggression and peer rejection among children with and without ADHD. Aggress. Behav. 2021, 47, 659–671.

- Nelson, J.M.; Gregg, N. Depression and anxiety among transitioning adolescents and college students with ADHD, dyslexia, or comorbid ADHD/dyslexia. J. Atten. Disord. 2012, 16, 244–254.

- Yang, H.-N.; Tai, Y.-M.; Yang, L.-K.; Gau, S.S.-F. Prediction of childhood ADHD symptoms to quality of life in young adults: Adult ADHD and anxiety/depression as mediators. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 3168–3181.

- Adler, L.D.; Nierenberg, A.A. Review of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHD. Postgrad. Med. 2010, 122, 184–191.

- Handelman, K.; Sumiya, F. tolerance to stimulant medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Literature review and case report. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 959.

- Childress, A.C.; Komolova, M.; Sallee, F.R. An update on the pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of ADHD with long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine formulations. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 937–974.

- van de Loo-Neus, G.H.H.; Rommelse, N.; Buitelaar, J.K. To stop or not to stop? How long should medication treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder be extended? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 584–599.

- Storebø, O.J.; Elmose Andersen, M.; Skoog, M.; Joost Hansen, S.; Simonsen, E.; Pedersen, N.; Tendal, B.; Callesen, H.E.; Faltinsen, E.; Gluud, C. Social skills training for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD008223.

- Mikami, A.Y.; Smit, S.; Khalis, A. Social Skills Training and ADHD—What Works? Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 93.

- Willis, D.; Siceloff, E.R.; Morse, M.; Neger, E.; Flory, K. Stand-alone social skills training for youth with ADHD: A systematic review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 348–366.

- Bashiri, A.; Ghazisaeedi, M.; Shahmoradi, L. The opportunities of virtual reality in the rehabilitation of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A literature review. Korean J. Pediatr. 2017, 60, 337–343.

- Corrigan, N.; Păsărelu, C.R.; Voinescu, A. Immersive virtual reality for improving cognitive deficits in children with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Virtual Real. 2023, 18, 1–20.

- Li, L.; Yu, F.; Shi, D.; Shi, J.; Tian, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q. Application of virtual reality technology in clinical medicine. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3867–3880.

- Adabla, S.; Nabors, L.; Hamblin, K. A scoping review of virtual reality interventions for youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 5, 304–315.

- Parsons, T.D.; Duffield, T.; Asbee, J.A. Comparison of virtual reality classroom continuous performance tests to traditional continuous performance tests in delineating ADHD: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2019, 29, 338–356.

- Romero-Ayuso, D.; Toledano-González, A.; Rodríguez-Martínez, M.D.C.; Arroyo-Castillo, P.; Triviño-Juárez, J.M.; González, P.; Ariza-Vega, P.; González, A.D.P.; Segura-Fragoso, A. Effectiveness of virtual reality-based interventions for children and adolescents with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Children 2021, 8, 70.

- Dechsling, A.; Orm, S.; Kalandadze, T.; Sütterlin, S.; Øien, R.A.; Shic, F.; Nordahl-Hansen, A. Virtual and augmented reality in social skills interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 4692–4707.

- Ke, F.; Moon, J.; Sokolikj, Z. Virtual reality–based social skills training for children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2022, 37, 49–62.

- Montoya-Rodríguez, M.M.; de Souza Franco, V.; Tomás Llerena, C.; Molina Cobos, F.J.; Pizzarossa, S.; García, A.C.; Martínez-Valderrey, V. Virtual reality and augmented reality as strategies for teaching social skills to individuals with intellectual disability: A systematic review. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2022.

- Baranowski, T. Descriptions for articles introducing a new game for health. Games Health J. 2014, 3, 55–56.

- Barkley, R.A. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 65–94.

- Brown, T.E. ADD/ADHD and impaired executive function in clinical practice. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2008, 10, 407–411.

- Sherlin, L.H.; Arns, M.; Lubar, J.; Heinrich, H.; Kerson, C.; Strehl, U.; Sterman, M.B. neurofeedback and basic learning theory: Implications for research and practice. J. Neurother. 2011, 15, 292–304.

- Ziegler, S.; Pedersen, M.L.; Mowinckel, A.M.; Biele, G. Modelling ADHD: A review of ADHD theories through their predictions for computational models of decision-making and reinforcement learning. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 633–656.

- Xin, Y. Influence of learning engagement on learning effect under a virtual reality (VR) environment. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 226–237.

- Cardona-Reyes, H.; Ortiz-Aguinaga, G.; Barba-Gonzalez, M.L.; Muñoz-Arteaga, J. User-centered virtual reality environments to support the educational needs of children with ADHD in the COVID-19 pandemic. IEEE Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Aprendiz. 2021, 16, 400–409.

- Zangiacomi, A.; Flori, V.; Greci, L.; Scaglione, A.; Arlati, S.; Bernardelli, G. An immersive virtual reality-based application for treating ADHD: A remote evaluation of acceptance and usability. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 205520762211432.

- Johnson, D.; Deterding, S.; Kuhn, K.-A.; Staneva, A.; Stoyanov, S.; Hides, L. Gamification for health and wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv. 2016, 6, 89–106.

- Gentry, S.; L’Estrade Ehrstrom, B.; Gauthier, A.; Alvarez, J.; Wortley, D.; van Rijswijk, J.; Car, J.; Lilienthal, A.; Tudor Car, L.; Nikolaou, C.K.; et al. Serious gaming and gamification interventions for health professional education. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD012209.

More