Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Giuseppe Andò and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

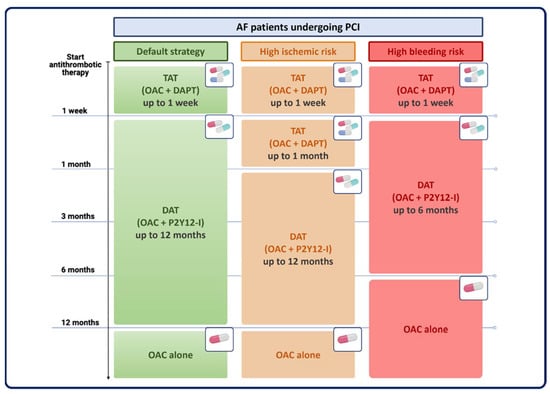

The antithrombotic management of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) poses numerous challenges. Triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT), which combines dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with oral anticoagulation (OAC), provides anti-ischemic protection but increases the risk of bleeding. Therefore, TAT is generally limited to a short phase (1 week) after PCI, followed by aspirin withdrawal and continuation of 6–12 months of dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT), comprising OAC plus clopidogrel, followed by OAC alone.

- DAPT

- triple antithrombotic therapy

- P2Y12 inhibitors

- atrial fibrillation

- PCI

- bleeding

1. Introduction

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy is recommended in several clinical conditions, with atrial fibrillation (AF) being the most common. Nowadays, more than 4 million people in Europe and 2 million in the U.S.A. suffer from AF [1]. As many as 20–30% of patients with AF undergo PCI, while approximately 10% of PCI candidates have chronic or new-onset AF, requiring long-term OAC [2][3][2,3]. Patients with AF usually require concomitant antiplatelet therapy following acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This clinical scenario represents a challenge for antithrombotic management due to the simultaneous need to prevent coronary thrombotic events, along with cerebrovascular and systemic embolism, while minimizing the risk of bleeding.

2. Antithrombotic Therapy in AF-PCI Patients: A Clinical Conundrum

Prevention of coronary ischemic events after PCI can be effectively achieved with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor [4][5][6][4,5,6], while long-term use of OAC provides protection against cerebrovascular and systemic embolism in patients with AF [2]. The combination of DAPT plus OAC, the so-called triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT), is effective in reducing atherothrombotic and cardioembolic risk. However, it has been associated with up to a 3-fold increase in bleeding complications compared with less intensive regimens [7][8][9][7,8,9]. The hemorrhagic risk associated with TAT depends on its duration and type, and both can be modulated to improve clinical outcomes. In most cases, TAT duration should be limited to the early (1 week) post-PCI phase, while 1-month TAT could be considered in selected patients with high ischemic and low bleeding risk. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have a better safety profile than vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and should be preferred as a first-line strategy (Figure 1). For concomitant antiplatelet therapy, early cessation of aspirin and continuation of the P2Y12 inhibitor clopidogrel plus OAC for 6–12 months is usually recommended, followed by OAC alone as a long-term maintenance strategy. Of note, the use of more potent agents, ticagrelor and prasugrel, in this setting is discouraged due to excessive bleeding hazards, and, therefore, they should be reserved for very selected cases. The above considerations summarize the results of several randomized trials conducted to determine the optimal pharmacological treatment of AF-PCI patients. Evidence from individual trials and subsequent study-level meta-analyses have been incorporated into current guidelines to provide practical algorithms for treatment decisions.

Figure 1. Antithrombotic strategies in AF-PCI patients according to individual ischemic and bleeding risk. AF = atrial fibrillation; DAPT = dual antiplatelet therapy; DAT = dual antithrombotic therapy; OAC = oral anticoagulation therapy; P2Y12-I = P2Y12 inhibitors; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; TAT = triple antithrombotic therapy.

3. Randomized Trials Comparing Different Antithrombotic Regimens in AF-PCI Patients

Several randomized trials have compared prolonged TAT regimens with less intensive antithrombotic strategies in patients with AF undergoing PCI (Table 1). Early studies included VKA-based anticoagulation in the experimental and control groups, thus essentially reflecting the comparison of single versus dual antiplatelet therapy in addition to VKAs [10]. After the introduction of DOACs, three randomized trials [11][12][13][11,12,13] were designed to compare dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT) with a DOAC (i.e., rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or edoxaban) versus TAT with a VKA. One trial, given its factorial design, compared both anticoagulation regimens (apixaban versus VKAs) and antiplatelet regimens (aspirin versus placebo) to provide definitive answers on whether the type and/or duration of TAT are relevant for practice [14][15][14,15]. Importantly, in all four randomized DOAC trials [11][12][13][15][11,12,13,15], DAT consisted of OAC plus a P2Y12 inhibitor (mostly clopidogrel) with early aspirin discontinuation after ACS or PCI, a combination regimen that was considered the most promising in this setting based on pharmacological and clinical considerations [11][12][13][15][11,12,13,15]. In this area, a recent sub-analysis of a randomized trial also provided additional evidence evaluating an abbreviated versus standard antiplatelet regimen in high bleeding risk (HBR) patients undergoing PCI with an indication for OAC [16][17][16,17]. Finally, two randomized trials evaluated the safety and efficacy of OAC with or without single antiplatelet therapy in the long-term (>1 year) after PCI.Table 1.

Randomized clinical trials including AF-PCI patients.

| Trial | Year | No. of Patients | Study Population | Experimental Group | Control Group | Key Endpoints | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOEST [10] | 2013 | 573 | OAC and PCI (ACS 27.1%) | OAC + P2Y12I (clopidogrel) for 1 to 12 months | OAC + P2Y12I (clopidogrel) + aspirin for 1 to 12 months | Any bleeding episode. | HR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.26–0.50; p < 0.0001 |

| ISAR-TRIPLE [18] | 2015 | 614 | OAC and PCI (ACS 32%) | OAC + P2Y12I (clopidogrel) + aspirin for 6 weeks |

OAC + P2Y12I (clopidogrel) + aspirin for 6 months. | Composite of ischemic events (death, MI, definite stent thrombosis, stroke) and TIMI major bleeding. | HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.68–1.91; p = 0.63 |

| PIONEER- AF PCI [13] |

2016 | 2124 | AF and PCI (ACS 51.6%) | OAC (rivaroxaban 15 mg/day) + P2Y12 I for 12 months (group 1); OAC (rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily) + DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (group 2). | VKA + DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (group 3). | Clinically significant bleeding (composite of major or minor bleeding according to TIMI criteria, and bleeding requiring medical attention). | HR (group 1 vs. group 3): 0.59; 95% CI: 0.47–0.76; p < 0.001. HR (group 2 vs. group 3): 0.63; 95% CI: 0.50–0.80; p < 0.001. |

| RE-DUAL PCI [12] | 2017 | 2725 | AF and PCI (ACS 64%) | OAC (dabigatran 110 mg or 150 mg twice daily) + P2Y12 I (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) | Warfarin + DAPT (aspirin + clopidogrel or ticagrelor) for 1 month (BMS) or 3 months (DES) | Major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding event (ISTH criteria) | HR (dabigatran 110 mg b.i.d.): 0.52; 95% CI: 0.42–0.63; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority; p < 0.001 for superiority. HR (dabigatran 150 mg b.i.d.): 0.72; 95% CI: 0.58–0.88; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority; p = 0.002 for superiority |

| ENTRUST-AF PCI [11] | 2019 | 1506 | AF and PCI (ACS 52%) | OAC (edoxaban 60 mg) + P2Y12I for 12 months | OAC (VKA) + DAPT for 1–12 months | Major bleeding or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (ISTH criteria) | HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.65–1.05; p = 0.001 for non-inferiority; p = 0.1154 for superiority. |

| AUGUSTUS [15] | 2019 | 4614 | AF and PCI (ACS 61.2%) | OAC (apixaban 5 mg bid or VKA) + P2Y12I for 6 months | OAC (apixaban or VKA) + DAPT for 6 months | Major bleeding or bleeding clinically relevant nonmajor (ISTH criteria) | HR (apixaban vs. VKA): 0.69; 95% CI: 0.58–0.81; p < 0.001 for both non-inferiority and superiority. HR (aspirin vs. placebo): 1.89; 95% CI: 1.59–2.24; p < 0.001. |

| MASTER DAPT [16] (OAC sub-analysis) |

2021 | 4579 (1666) | HBR and PCI after 1-month DAPT (OAC indication) (ACS 42.2%) |

Abbreviated DAPT regimen (SAPT for 5 months + OAC) | Standard DAPT regimen (DAPT for 2 months + SAPT until 11 months + OAC) | First co-primary endpoint: NACE (death, MI, stroke, and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding) Second co-primary endpoint: MACCE (death, MI, or stroke) Third co-primary endpoint: major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleedings (BARC type 2, 3, or 5) |

HR (NACE): 0.83; 95% CI; 0.60–1.15; p = 0.26. HR (MACCE): 0.88; 95% CI; 0.60–1.30. HR (BARC 2, 3 or 5): 0.83; 95% CI; 0.62–1.12; p = 0.25. |

| OAC-ALONE [19] | 2019 | 696 | AF beyond 1 year after PCI | OAC for 12 months | OAC + SAPT for 12 months | Primary endpoint: all-cause death, MI, stroke, or systemic embolism. Major secondary endpoint: primary endpoint or major bleeding (ISTH criteria). |

HR (primary endpoint): 1.16; 95% CI: 0.79–1.72; p = 0.20 for non-inferiority, p = 0.45 for superiority. HR (major secondary endpoint): 0.99; 95% CI, 0.71–1.39; p = 0.016 for non-inferiority, p = 0.96 for superiority. |

| AFIRE [20] | 2019 | 2236 | AF and PCI or CABG (>1 year earlier) or CAD not requiring revascularization | OAC (rivaroxaban) for 6 months | OAC (rivaroxaban) + SAPT for 6 months | Primary efficacy endpoint: stroke, systemic embolism, MI, unstable angina requiring revascularization, or death from any cause. Primary safety endpoint: major bleeding (ISTH criteria). |

HR (efficacy endpoint): 0.72; 95% CI: 0.55–0.95; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority. HR (safety endpoint): 0.59; 95% CI: 0.39–0.89; p = 0.01 for superiority. |

| OPTIMA-3 [21] | 2024 (study completion estimated) | 2274 | AF and PCI (ACS 100%) | OAC (warfarin) + DAPT for 1 month, followed by SAPT (clopidogrel) up to 12 months | OAC (warfarin) + DAPT (clopidogrel + aspirin) for 6 months, followed by SAPT (clopidogrel) up to 12 months | Primary endpoint: MACCE at 12 months. Major secondary endpoint: major bleeding or bleeding clinically relevant nonmajor (ISTH criteria). |

Ongoing |

| OPTIMA-4 [21] | 2024 (study completion estimated) | 1472 | AF and PCI (ACS 100%) | OAC (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily) + SAPT (clopidogrel) up to 12 months | OAC (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily) + SAPT (ticagrelor) up to 12 months | Primary efficacy endpoint: MACCE at 12 months Primary safety endpoint: Major bleeding or bleeding clinically relevant nonmajor (ISTH criteria). |

Ongoing |

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; AF = atrial fibrillation; BARC= Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; BMS = bare metal stent; CABG = coronary Artery Bypass Graft; CAD = coronary artery disease; DAPT = dual antiplatelet therapy; DES = drug-eluting stent; HBR = high bleeding risk; ISTH = International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; MACCE = major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event; MI = myocardial infarction; NACE = net adverse clinical events; OAC = oral anticoagulation therapy; P2Y12I = P2Y12 inhibitors; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; SAPT = single antiplatelet therapy; TIMI = Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction; VKA = vitamin K antagonists.

3.1. Randomized Trials of Antithrombotic Strategies within One Year after PCI

The WOEST trial [10] (What is the Optimal antiplatElet and Anticoagulant Therapy in Patients With Oral Anticoagulation and Coronary StenTing) randomized 573 PCI patients on OAC for AF (69%) or other medical conditions (31%) to receive clopidogrel alone (DAT group) or clopidogrel plus aspirin (TAT group) using an open-label design. The primary outcome of any bleeding episode within one year post-PCI occurred in 19.4% of patients receiving DAT and in 44.4% of those receiving TAT (HR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.26–0.50; p < 0.0001). DAT was also associated with a lower incidence of the composite secondary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, target-vessel revascularization, and stent thrombosis compared to TAT (HR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.38–0-94; p = 0.025). The ISAR-TRIPLE [18] (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen-Testing of a 6-Week Versus a 6-Month Clopidogrel Treatment Regimen in Patients With Concomitant Aspirin and Oral Anticoagulant Therapy Following Drug-Eluting Stenting) trial was designed to evaluate whether reducing the duration of TAT from six months to six weeks by discontinuing clopidogrel in patients receiving concomitant aspirin and OAC after PCI with a drug-eluting stent (DES), improved the net clinical outcome of death, MI, definite stent thrombosis, stroke, or major bleeding at nine months. The trial randomized 614 patients to 6-week TAT versus 6-month TAT and showed no significant difference between the two treatment strategies in terms of the primary net clinical outcome (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.68–1.91; p = 0.63). Similarly, no difference was observed in the key efficacy endpoint of cardiac death, MI, definite stent thrombosis, and ischemic stroke or the key safety endpoint of major bleeding. Starting the DOAC era, the PIONEER-AF PCI [13] (Open-Label, Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Study Exploring Two Treatment Strategies of Rivaroxaban and a Dose-Adjusted Oral Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment Strategy in Subjects with Atrial Fibrillation who Undergo Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial randomized 2124 patients with non-valvular AF undergoing PCI into three groups: rivaroxaban 15 mg once daily plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months (group 1); rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (group 2); standard therapy with a VKA plus DAPT for 1, 6, or 12 months (group 3). Rivaroxaban 15 mg or 2.5 mg plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months was associated with lower rates of clinically significant bleeding (16.8% in group 1, 18.0% in group 2, and 26.7% in group 3; HR for group 1 vs. group 3: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.47–0.76, p < 0.001; HR for group 2 vs. group 3: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.50–0.80, p < 0.001) with similar efficacy in terms of major adverse cardiovascular events (6.5% in group 1, 5.6% in group 2, and 6.0% in group 3; p values were not significant for all comparisons). In the RE-DUAL PCI [12] (Randomised Evaluation of Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran versus Triple Therapy with Warfarin in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial, 2725 patients with AF-PCI were randomized to receive TAT with warfarin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor and aspirin for 1–3 months or DAT with clopidogrel or ticagrelor plus dabigatran 110 mg or 150 mg twice daily. The incidence of the primary endpoint (major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding event, defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH)) was 15.4% in the DAT group with dabigatran 110 mg compared to 26.9% in the TAT group (HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.42–0.63; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority; p < 0.001 for superiority) and 20.2% in the DAT group with dabigatran 150 mg compared to 25.7% in the TAT group (HR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.58–0.88; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority). In addition, DAT was not inferior to TAT for preventing thromboembolic events (HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.84–1.29; p = 0.005 for non-inferiority). The ENTRUST-AF PCI [11] (Edoxaban Treatment Versus Vitamin K Antagonist in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) trial randomized 1506 AF-PCI patients to DAT with edoxaban 60 mg once daily plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months or TAT with a VKA for 1–12 months. The edoxaban-based regimen was not inferior to the VKA-based regimen regarding bleeding (HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.65–1.05; p = 0.001 for non-inferiority), with no significant differences in ischemic events. In the AUGUSTUS trial [15] (An Open-label, 2-by-2 Factorial, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety of Apixaban vs. Vitamin K Antagonist and Aspirin vs. Placebo in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Acute Coronary Syndrome and/or Percutaneous Coronary Intervention), the only DOAC trial with a 2-by-2 factorial design, 4614 patients were randomized to receive apixaban or a VKA plus aspirin or placebo for six months. Major and clinically relevant bleeding events were observed in 10.5% of the patients receiving apixaban compared to 14.7% of those receiving VKA (HR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.58–0.81; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority and superiority) and in 16.1% of patients receiving aspirin compared to 9.0% of those receiving placebo (HR: 1.89; 95% CI: 1.59–2.24; p < 0.001). Patients on apixaban had a lower incidence of death or hospitalization than those in the VKA group (23.5% vs. 27.4%; HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.74–0.93; p = 0.002) and a similar incidence of ischemic events. In summary, the antithrombotic regimen with apixaban without aspirin resulted in less bleeding and fewer hospitalizations, with no significant differences in the incidence of ischemic events, compared with regimens with a VKA, aspirin, or both. In the MASTER DAPT trial [16] (Management of High Bleeding Risk Patients Post Bioresorbable Polymer Coated Stent Implantation with an Abbreviated Versus Standard DAPT Regimen), 4579 patients at HBR were randomized after 1-month DAPT to abbreviated or standard antiplatelet therapy. Randomization was stratified by concomitant OAC indication. In the population with an OAC indication (N = 1666), at one month from PCI, patients changed immediately to single antiplatelet for five months (abbreviated regimen) or continued ≥ 2 months of dual antiplatelet and single antiplatelet (standard regimen). No difference was observed for the co-primary endpoints of net adverse clinical outcomes of death, MI, stroke, or Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 3 or 5 bleeding (HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.60–1.15); nor were differences observed in the major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE) of death, MI, or stroke (HR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.60–1.30), and BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding (HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.62–1.12) between abbreviated versus standard antiplatelet regimens in addition to long-term OAC. Of note, in the per-protocol analysis of the trial, including the MASTER DAPT adherent OAC population, discontinuation of single antiplatelet therapy six months after PCI was associated with similar MACCE and lower BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding (HR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.22–0.99) than single antiplatelet therapy continuation, suggesting the potential benefit of this strategy [22]. Several issues should be considered when interpreting these findings. None of the trials discussed above were powered to draw definitive conclusions about the anti-ischemic efficacy of DAT versus TAT, especially for relatively rare events, such as stent thrombosis [7][13][18][7,13,18]. In all DOAC trials, aspirin was not discontinued at the time of PCI; therefore, patients in the DAT groups also received TAT after PCI for variable periods (up to 72 h in PIONEER-AF PCI, 120 h in RE-DUAL PCI, 14 days in AUGUSTUS, and 5 days in ENTRUST-AF PCI). There is also no conclusive evidence on whether aspirin or clopidogrel should be part of the DAT, and data on potent P2Y12 inhibitors are limited [4][12][4,12]. Finally, it should be noted that the evidence in high-risk patients, including those undergoing complex PCI or presenting with ACS, is derived from subgroup analyses of randomized trials and remains exploratory. In particular, specific subsets, such as patients with ST-segment elevation MI, were underrepresented in these trials (i.e., less than 10% of the trial populations); therefore, caution should be exercised when extending these results to these patients.3.2. Randomized Trials of Antithrombotic Strategies beyond One Year after PCI

The OAC-ALONE trial [19] (Optimizing Antithrombotic Care in Patients With AtriaL fibrillatiON and Coronary stEnt) was designed to compare a single-drug strategy of OAC alone with a combination strategy of OAC plus single antiplatelet agent (aspirin or clopidogrel) in patients with AF from one year after stent implantation onwards. The study initially planned to enroll 2000 patients over 12 months but was terminated early after enrolling 696 patients over 38 months. The primary endpoint of all-cause death, MI, stroke, or systemic embolism was observed in 15.7% of patients treated with OAC alone and 13.6% of patients treated with OAC plus a single antiplatelet agent, not achieving the non-inferiority for the ischemic endpoint (HR: 1.16; 95% CI: 0.79–1.72; p = 0.20 for non-inferiority, p = 0.45 for superiority). The key secondary endpoint of all individual ischemic endpoints and ISTH major bleedings occurred in 19.5% of OAC-alone patients and 19.4% of those receiving OAC plus an antiplatelet agent (HR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.71–1.39; p = 0.016 for non-inferiority, p = 0.96 for superiority). Overall, the trial was underpowered and inconclusive regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of the two strategies. More recently, the AFIRE [20] (Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic Events with Rivaroxaban in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease Study) trial included 2236 patients with AF and established chronic coronary disease who had undergone PCI (1564 patients, 71.4% of whom with at least one DES) or coronary artery bypass grafting (252 patients, 11.4%) more than one year earlier or were managed medically. Patients were randomized to receive rivaroxaban monotherapy (15 mg daily for patients with a creatinine clearance of ≥50 mL/min, 10 mg daily for those with a creatinine clearance of 15–49 mL/min) or combination therapy with rivaroxaban plus a single antiplatelet agent. Rivaroxaban monotherapy was non-inferior to combination therapy for the primary efficacy endpoint of death, stroke, systemic embolism, MI, or unstable angina requiring revascularization (HR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.55–0.95; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority) and was superior for the primary safety endpoint of major bleeding (HR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.39–0.89; p = 0.01 for superiority). In the subgroup analysis by revascularization strategy, the point estimate of the treatment effect for the primary endpoint was numerically in favor of rivaroxaban monotherapy in the PCI subgroup (HR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.45–0.85) but not in the CABG subgroup (HR: 1.19; 95% CI: 0.67–2.11). The trial was stopped early due to increased mortality with the combination therapy, and its results support current recommendations to discontinue antiplatelet therapy at 12 months after PCI and continue with OAC monotherapy. Of note, the inclusion of only East Asian patients and the Japanese-approved dose of rivaroxaban (10 mg or 15 mg once daily, depending on creatinine clearance) instead of the globally approved daily dose of 20 mg should be considered when interpreting these results.4. Synthesis of Evidence from Meta-Analyses

Pivotal AF-PCI trials, each with a relatively small sample size distributed across multiple treatment arms, were generally designed to detect superiority for bleeding events and non-inferiority for ischemic events [11][12][13][15][11,12,13,15]. However, none had enough statistical power to explore rare events such as stent thrombosis or intracranial bleeding. To this purpose, meta-analyses are useful to enhance statistical power and more accurately determine the clinical impact of multiple antithrombotic treatment strategies on such uncommon events. Given the immense complexity of treatment decisions for AF patients undergoing PCI or with ACS—considering antithrombotic type, duration, and dosage, which could result in hundreds of thousands of possible treatment permutations—it’s unsurprising that numerous articles have been published [23]. Despite only seven randomized trials investigating the impact of DAT or TAT in these patients [10][11][12][13][15][18][24][10,11,12,13,15,18,24], over 80 meta-analyses have been published. This abundance of meta-analyses arises because attempts to summarize evidence have been associated with various interpretations of data from the available trials. Specifically, the main differences in results from these meta-analyses are linked to diverse approaches to study inclusion, endpoint selection, timing, and treatment type and dosage. These are summarized in Table 2. In general, all published meta-analyses confirm original findings from individual trials that DAT is associated with a reduction of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding compared with TAT. Golwala et al., in one of the first studies published in the field, confirmed that DAT, compared with TAT, was associated with a 47% reduction of TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) major and minor bleeding, maintaining a substantial equipoise in terms of trial-defined MACE [25]. This meta-analysis published in 2018 lacked the more definitive evidence provided by two additional pivotal AF-PCI trials, AUGUSTUS and ENTRUST-AF-PCI, which were available later. An updated meta-analysis by Gargiulo et al. [26] evaluated the impact of DAT compared to TAT, including all four pivotal AF-PCI trials, and encompassed 10,234 patients. In this study, DAT was associated with a 44% reduction of ISTH major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding and a 46% reduction of ISTH major bleeding [26]. Regarding ischemic endpoints, while prior meta-analyses confirmed no difference between DAT and TAT in terms of MACE, Gargiulo et al. suggested a possible increase of ischemic events in patients assigned to DAT, with a 59% increase in trial-defined stent thrombosis and a borderline increase in MI [26]. This was also confirmed by Andò et al., who found that DAT was associated with a significant 54% increase in stent thrombosis, a 23% increase in MI, a significant increase in cardiovascular mortality without impacting all-cause mortality or study-defined MACE [27]. The signal for higher rates of ischemic events with DAT was primarily driven by an excess of ischemic events in patients assigned to DAT with dabigatran 110 mg. A dedicated analysis of the AUGUSTUS trial also highlighted a possible increase in stent-related events in the first 30 days after the procedure in patients assigned to DAT [28]. This underscores, for the first time, the presence of a possible trade-off between ischemic and bleeding events to be considered in patients assigned to DAT or TAT. Notably, while a bleeding-ischemic event trade-off was observed, overall rates of bleeding events largely surpassed those of ischemic events, reflecting a lower number needed to treat with DAT to obtain a bleeding benefit compared to preventing rarer events such as stent thrombosis or MI. In this context, several elements have been suggested by international guidelines to base treatment decisions in these cases [29][30][31][29,30,31]. Clinical presentation has been considered a possible element to highlight a higher ischemic risk population that might benefit from a longer initial treatment with TAT. Therefore, Gargiulo et al. specifically explored the impact of DAT compared to TAT in 10,193 patients with ACS or CCS [32]. They found that irrespective of clinical presentation, DAT was associated with a similar reduction of ISTH major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding in both patients with ACS and CCS, where a reduction of 37% and 32%, respectively, was observed, with negative interaction testing [32]. In both subgroups, there was no difference between DAT and TAT for all-cause death, MACE, or stroke. However, MI and stent thrombosis were numerically higher with DAT versus TAT consistently in ACS and CCS [32].Table 2.

Differential elements considered in AF-PCI meta-analyses.

| Differential Elements Considered in AF-PCI Meta-Analyses |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; AF = atrial fibrillation; DAT = dual antithrombotic therapy; OAC = oral anticoagulation therapy; P2Y12I= P2Y12 inhibitors; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; TAT = triple antithrombotic therapy; VKA = vitamin K antagonists; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

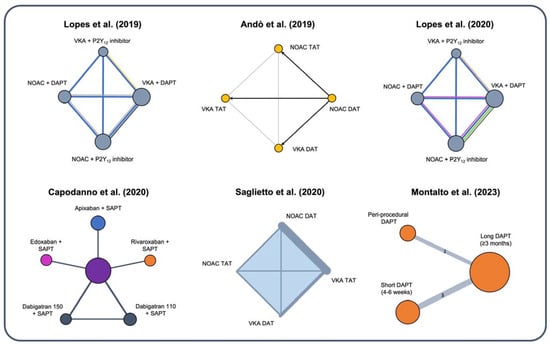

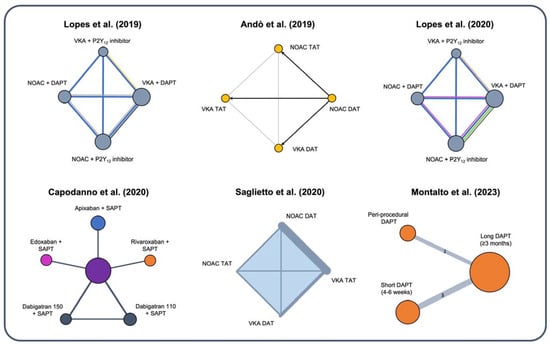

Several network meta-analyses attempted to indirectly compare various treatment options with diverse designs (Figure 2) [27][33][34][35][36][37][27,33,34,35,36,37]. Lopes et al. included five randomized trials and 11,542 patients based on four different treatment types: NOAC + DAPT, NOAC + SAPT, VKA + DAPT, and VKA + SAPT [34]. They found that compared with VKA + DAPT, regimens of VKA-based and NOAC-based DAT were associated with a 43% and 48% reduction in TIMI major bleeding, respectively. All four treatments explored showed a similar risk of MACE [34]. Similarly, Saglietto et al. showed that both VKA and NOAC-based DAT regimens reduced the occurrence of TIMI major bleeding by 38% and 48%, respectively, but only NOAC-based DAT significantly reduced ICH by 67% compared to VKA-based TAT [35]. No difference in MACE was observed among the different explored treatment strategies, and a trend toward higher risks of ST was observed for NOAC-based DAT compared to both VKA and NOAC-based TAT. Capodanno et al. performed a network meta-analysis by including four trials, while the multiple treatment arms accounted for the different types of OAC associated with DAT or TAT [36]. They consistently found that NOAC-based DAT was associated with a 44% reduction of clinically significant bleeding. Interestingly, in this analysis, indirect comparisons taking into account the possible impact of different OAC types on overall safety performance showed that the safety profile of NOAC-based DAT might be affected by the type of OAC implemented, with a signal towards the highest safety of an apixaban-based DAT [36]. These studies confirmed that NOACs provide a more beneficial safety profile than VKA in an AF-PCI population and that a NOAC-based DAT strategy should be preferred. Nevertheless, the possible trade-offs in specific patients with a higher risk for stent-related events should be accounted for.

Importantly, most trials, and consequently the resulting evidence from meta-analyses, predominantly tie the safety and efficacy impact of DAT to NOAC therapy compared to a VKA-based TAT. As VKA is no longer the standard of care in AF-PCI patients and is no longer an informative comparator, it is crucial to evaluate the impact of DAT vs. TAT by unlinking OAC from the antiplatelet therapy regimen. Indeed, it is well-established that NOACs are associated with a reduced risk of bleeding per se compared to VKA, which could confound the impact of DAT vs. TAT irrespective of the antiplatelet regimen implemented [38]. To address this specific question, a recent meta-analysis by Montalto et al. explored the impact of DAPT and its duration, irrespective of the type of OAC, specifically excluding all trials that tied antiplatelet and anticoagulant strategy together [37]. Specifically, this meta-analysis aimed to determine the optimal duration of DAPT after PCI in patients with any indication for OAC. The study included five randomized clinical trials (N = 7665) that exclusively randomized patients to DAPT duration after PCI and excluded studies that tied the randomization process of DAT vs. TAT to OAC type [37]. The results suggest that abbreviated DAPT (i.e., periprocedural or up to 6 weeks) compared to prolonged DAPT (3 months or longer) in association with OAC is associated with a significant reduction of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding and major bleeding (RR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.52–0.91; p = 0.01 and RR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.52–0.95; p = 0.01, respectively) with no difference for MACE (RR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.70–1.33; p = 0.6), all-cause death, cardiovascular death, stent thrombosis, or MI [37]. A network meta-analysis comparing three different treatment strategies, namely peri-procedural TAT, short TAT for 4–6 weeks, and longer TAT for ≥3 months, showed that peri-procedural TAT had the highest probability of preventing clinically relevant non-major bleeding and major bleeding, while still having the highest probability of ranking better for MACE compared to the other two treatment strategies [37].

Importantly, most trials, and consequently the resulting evidence from meta-analyses, predominantly tie the safety and efficacy impact of DAT to NOAC therapy compared to a VKA-based TAT. As VKA is no longer the standard of care in AF-PCI patients and is no longer an informative comparator, it is crucial to evaluate the impact of DAT vs. TAT by unlinking OAC from the antiplatelet therapy regimen. Indeed, it is well-established that NOACs are associated with a reduced risk of bleeding per se compared to VKA, which could confound the impact of DAT vs. TAT irrespective of the antiplatelet regimen implemented [38]. To address this specific question, a recent meta-analysis by Montalto et al. explored the impact of DAPT and its duration, irrespective of the type of OAC, specifically excluding all trials that tied antiplatelet and anticoagulant strategy together [37]. Specifically, this meta-analysis aimed to determine the optimal duration of DAPT after PCI in patients with any indication for OAC. The study included five randomized clinical trials (N = 7665) that exclusively randomized patients to DAPT duration after PCI and excluded studies that tied the randomization process of DAT vs. TAT to OAC type [37]. The results suggest that abbreviated DAPT (i.e., periprocedural or up to 6 weeks) compared to prolonged DAPT (3 months or longer) in association with OAC is associated with a significant reduction of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding and major bleeding (RR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.52–0.91; p = 0.01 and RR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.52–0.95; p = 0.01, respectively) with no difference for MACE (RR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.70–1.33; p = 0.6), all-cause death, cardiovascular death, stent thrombosis, or MI [37]. A network meta-analysis comparing three different treatment strategies, namely peri-procedural TAT, short TAT for 4–6 weeks, and longer TAT for ≥3 months, showed that peri-procedural TAT had the highest probability of preventing clinically relevant non-major bleeding and major bleeding, while still having the highest probability of ranking better for MACE compared to the other two treatment strategies [37].

Figure 2. Different designs of recent network meta-analyses evaluating optimal treatment in AF patients with ACS or undergoing PCI [27][33][34][35][36][37][27,33,34,35,36,37]. DAPT = dual antiplatelet therapy; DAT = dual antithrombotic therapy; NOAC = novel oral anticoagulants; SAPT = single antiplatelet therapy; TAT = triple antithrombotic therapy; VKA = vitamin K antagonist.