Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lindsay Dong and Version 1 by Gilberto Galindo.

Children from rural areas face numerous possibilities of neurodevelopmental conditions that may compromise their well-being and optimal development. Neuropsychology and electroencephalography (EEG) have shown strong agreement in detecting correlations between these two variables and suggest an association with specific environmental and social risk factors.

- electroencephalography

- infant welfare

1. Introduction

Impaired cognitive development under risk conditions depends on different factors and how much they affect one another. Common causes compromising the cognitive and central nervous system (CNS) are often observed in disadvantaged social groups such as rural entities living in poverty [1]. The emergence of developmental cognitive neuroscience in the field of rurality research is both revolutionary and difficult; it represents difficulties stemming from both implicit and overt assumptions underlying this discipline. It requires a variety of rational theoretical alternatives for hypothetical psychological processes. The studies in this field might relate to particular brain functions and how various experimental events at various levels are connected. Studies reveal evidence of low socioeconomic status as a factor influencing neurocognitive differences between children from different socioeconomic backgrounds [2], including academic achievement and psychiatric outcomes but particularly language and executive functioning [3,4][3][4]. Neuroimaging studies have consistently evidenced patterns of association between socioeconomic status and brain development [5]; however, compared to other neuroimaging techniques, electroencephalography (EEG) is a viable clinical diagnostic and research technique. It is economically accessible, non-invasive, functionally sensitive, temporarily precise, and continuously improved for further complex feature extraction in different clinical conditions [6,7][6][7]. Classification methods for the sensitive detection of differences between normal and cognitively impaired subjects through the analysis of the electrical activity in the brain have been explored and have shown good reliability, even using a small number of electrodes [8,9][8][9]. The EEG functionally probes the CNS to obtain a real-time record of electrical activity [10]. The origin of these electrical signals is in the pyramidal cells of the cerebral cortex; each neuron contains an electrical dipole that can be inhibitory or excitatory depending on the cell [11]. In this way, the method collects and records spectral information about the electrical activity from different brain regions through electrodes placed on the surface of the skull to capture the potential difference between them [12]. The standard EEG is a non-invasive, painless technique in which surface electrodes are attached to the scalp by a conductive gel and positioned according to the international 10–20 system. The voltage is measured between two electrodes. Usually, 16 to 24 electrodes are used for clinical purposes [13,14][13][14]; however, for research purposes, the number of electrodes can reach 128 electrode channels. Today, digital amplifiers are used, which facilitates signal analysis and storage as well as the ability to change parameters such as filters, sensitivity, recording time, and settings. A standard EEG, including activation techniques, primarily intermittent photostimulation and hyperventilation, should last at least 30 min [15]. These techniques are designed to provoke or enhance the appearance of abnormalities in brain activity. Neuron-related potentials recorded in the EEG are derived from the electrical activity of excitable tissues and gathered by measuring the potential difference between a scanner electrode and a reference electrode to investigate the biophysical basis of potentials of neuronal origin.

On the other hand, the conditions of rural development are part of society’s history. They are not a new public health concern. However, most diagnoses related to brain maturation, specifically using EEG techniques, prevention, or treatment methods, are often developed and implemented in urban facilities, leading to challenges for rural living children [16,17][16][17]. Rurality in definition has wide variance; the Office Management and Budget (OMB) and other census institutions are often good resources for defining conditions for rural development. Accordingly, a rural area is defined as a nonmetropolitan area in which there is neither a city nor an urbanized area with 50,000 or more inhabitants, and the culture of the population who live in this condition is shaped by density, geography, agricultural heritage, economic conditions [18], social styles [19], religion, behavioral norms, and health care. Usually, there is a significant distance to health care services, different from urban communities [20], particularly neuropsychology and psychophysiology practice in rural settings [21], as well environmental factors that affect the nervous system like air pollution [22]. Rural areas represent disparities in health risk factors compared to urban residential assets. Rural residents usually demonstrate higher smoking rates and crude alcohol consumption [23]. The status of poverty or malnutrition is associated with behavioral conditions, such as depression in children [24]. A growing body of research shows that the fetal environment affects brain development and determines the brain’s trajectory throughout the lifespan, particularly factors such as fetal alcohol exposure, teratogen exposure, and nutrient deficiencies [25].

These issues considerably influence and mold behavioral, mental health, and cognitive features. For example, the impact of mental health disorders and cognitive impairment in rural areas is higher compared to urban areas [26]. Children lack basic assets for a good quality of life, directly related to risk-taking behaviors and non-optimal cognitive development [27]. The literature suggests that neonatal mortality and morbidity are higher in rural and marginalized regions due to economic constraints, the absence of specialized obstetric and neonatal services, and the lack of awareness of the dangers to maternal and fetal health during pregnancy [28], which are linked to a higher prevalence of risk factors for early brain damage such as very preterm birth, low birth weight, hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy, exposure to substances and maternal diseases, as well as septic processes [29]. In the case of the presence of early signs of neonatal seizures, EEG monitoring provides predictors related to unfavorable neurological signs, particularly in infants who experienced perinatal risks [30]. All these variables have been associated with an increased risk of neurocognitive developmental disorders.

Rural children, as compared with urban, show lower accuracy in visuospatial tasks measured by global and local visual features recognition and speed processing; they also present difficulties in internal image objects and visual memory [31]. According to this study, the lower abilities in visual feature processing relate to other neuropsychological domains such as letter processing, leading to the possibility of developing dyslexia, which according to Barbeiro and collaborators [32] is a widely underestimated neurodevelopmental disorder. A systematic review from Cainelli and collaborators [33] proposes that although learning disorders such as dyslexia have been widely studied, their brain electrophysiological causes remain not completely understood. In the report, they found most of the studies using spectral analysis of the EEG in resting states, including the specifics for activation or decrease in different brain lobes, as well as the non/significant differences.

2. Electroencephalography in Rural Children at Neurodevelopmental Risk

2.1. Qualitative Synthesis

2.1.1. EEG in Children at Neurodevelopmental Risk

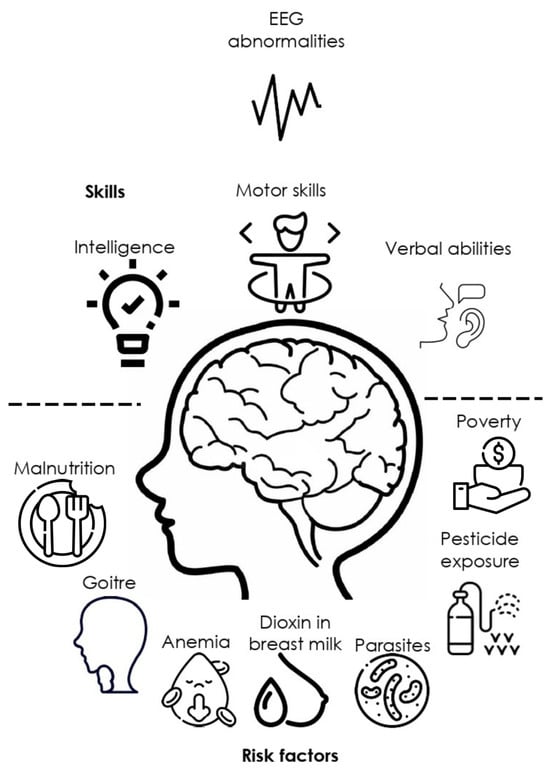

Living in rural areas is not a cognitive or central nervous system (CNS) development risk factor per se. However, this condition is frequently associated with exposure to pesticides affecting health [41][34], low-income [42][35], malnutrition in children and their parents [43][36], conditions which may directly or indirectly lead to cognitive impairment and electrophysiological abnormalities (Figure 21). Previous research seeking to describe an association between rurality and risk factors affecting mental health has shown that low schooling is the main related factor [44][37]. This problem is increased with the characteristics of rural communities that challenge the neuropsychological service delivery due to resource limitations, distance and costs, professional isolation, and beliefs about psychological services that reduce reliability all over these services [21].

Figure 21.

Main social, ecological, and health factors associated with EEG abnormalities and cognitive impairment.

Ueda and collaborators demonstrated a difference in frontal and occipital power variance function in the theta and alpha bands to be smaller in participants presenting mild cognitive impairment compared with healthy subjects [45][38]. Few studies have reported EEG features of suboptimal or impaired cognitive development in recent years. Rural or vulnerable environment development conditions characterized by low to middle income, farm-working as a sustainable productive activity, lack or deficient drain systems, treated water services at homes, nutrition deficiencies, and toxin exposure are linked to different particular neuropsychological and neurophysiological EEG features [46][39], which could be a predictive factor for anticipating risk or protective factors. However, these studies offer a clear direction about the relevance of EEG features for analyzing cognitive development in children from at-risk rural environments.

Later IQ scores can be predicted employing EEG pattern-measuring strategies even during early neonatal development periods, as suggested by previous studies. For example, in their study, Beckwith and Parmelee [47][40] proposed three visual methods to analyze EEG in preterm infants, one to describe unusual EEG patterns, a second to code the persistent remarkable delay on EEG maturation, and a third to describe the distribution of patterns within and across states of consciousness. Their results suggest that the integrity of the electrical neurophysiological organization of the brain has implications for later development, as measured in five-year follow-ups. Other severe EEG abnormalities such as epileptiform signs [48][41] and stress exposure have also been underestimated in at-risk populations. Several neuropsychological and EEG features have proven to have a high sensitivity to indicate a possible neurophysiological decline in conditions such as Parkinson’s disease [49][42], autism [50][43], epilepsy [51][44], parental history of alcohol consumption [52][45], as well as cognitive impairment in areas such as memory, attention, language, and school success [53][46].

Thus, neuropsychological tests and EEG analysis are useful tools for studying cognitive impairment in at-risk populations. For example, qEEG analysis in Pakistani children suggested gamma power as a neural marker of cognitive function, specifically associated with executive function and verbal IQ [54][47]. Cognitive impairment in vulnerable rural populations is often severely underestimated or mistaken for other common developmental disorders. This is partly because most children with, for example, attention problems are impulsive and have low academic achievement. However, the cognitive and behavioral deficits associated with attention disorders are related to different brain impairments, such as less effective executive function, increased frontal theta waves, and a deficit in selective modulation of cortical activity [55][48]. Moreover, this underestimation is also due to the difficulty distinguishing between neurotypical development and mild cognitive impairment at the cognitive and electrophysiological levels.

In the same direction, the literature has widely reported that severe health risks are not the only condition causing abnormalities in children’s bioelectrical functional state, with a significant association with other cognitive processes. In a study with 172 children, 10 to 12 years old, children with slight deficits in executive functions showed signs of suboptimal functional states of the limbic structures. Most evident behavioral deficits were related to motor and tactile perseverations and deviations in emotional–motivational regulation, such as poor motivation in task performance and poor communication skills, according to the authors [56][49].

2.1.2. EEG, Environmental, and Social Risk Factors

Environmental exposure to toxins is present in rural and urban facilities, which leads to toxic concentrations of these compounds in different regions of the CNS. Furthermore, they may have a neurobiological effect even during prenatal in utero stages [70][50], leading to future developmental consequences. For example, exposure to lead and cadmium in children with learning disabilities in a rural population is related to differences in IQ performance, demonstrating that higher lead concentrations measured from hair are inversely correlated with intelligence and brain functioning [71][51].

The low income in rural areas is, at the same time, a multiphasic factor that is allocated to different situations in adverse developmental settings. Children growing up under vulnerable conditions are frequently exposed to higher levels of stress due to stressful home environments explained by low income [72][52], anxiety [73][53], as well as prenatal cortisol exposure from the stressed mother [74][54]. Stress-related neurochemicals in early childhood, measured utilizing cortisol concentrations, are associated with impaired development of executive functions. In their study, Blair and Berry [75][55] describe findings that indicate children from 7 to 48 months with lower cortisol levels under resting conditions perform better on a battery of executive functions tasks. On the other hand, there there has been an advancement in the understanding of electrical neural activity assessed by using EEG. EEG power can be quantified among the different frequency bands and has been proven to be associated with different cognitive processes.

2.2. Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis was taken from 11 studies reporting EEG abnormalities, mainly related to epileptic EEG features and seizure history. According to the data from children from rural areas, the reports have in common a first recognition based on epileptic history and a particular characterization of EEG features. Six studies report a significant association between EEG abnormalities and cognitive impairment; the standard calculation from three studies showed a significant correlation between the two variables. A variety of poverty-related risk factors are commonly presented to infants and young children in low- and middle-income countries, increasing the possibility that these individuals may experience poor neurodevelopmental outcomes [79][56]. For the first instance, according to results from studies [80][57], inequalities in children’s and teenagers’ access to health care services and sociodemographic factors are considered as risk factors and are still present despite medical insurance coverage; for example, place of residence (rural/small city) showed a p < 0.01. In particular, reports of the presence of malnutrition [81][58], acute encephalopathy, head injury before seizure onset, unfavorable prenatal events, and acute encephalopathy were the most likely proximate causes of convulsive features (p < 0.001) according to this analysis. Another significant association (p < 0.001) was found for data from children living in rural areas who presented co-morbidity of attention deficit with hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy [82][59]. Epilepsy and unfavorable prenatal occurrences have a high association according to research data [83][60]. Access inequities to treatments in children who present neurodevelopmental risks are commonly reported; for example, sociodemographic research [80][57] showed that children with epilepsy aged 1 to 5 years old as opposed to other children and adolescents and children with epilepsy as opposed to children living in smaller cities and rural areas were more likely to receive specialized attention by neuropediatricians. Other countries, for example, reported that ERPs are effective for assessing children in rural areas [84,85][61][62] and are a useful tool to describe the neurophysiological maturity of the brain for the processing of visual novel information as well as face and auditory processing. Non-optimal development of sensorial brain systems such as brain somatomotor [89][63], or frontostriatal and cerebellar circuitry [90,91][64][65] can lead to clinical co-morbidity with ADHD.3. Summary

EEG is perhaps the most advantageous technique for research and diagnosis to implement in at-risk rural conditions. Neurophysiological factors underlie different cognitive impairment expressions, often underestimated in rural environments [39][66]. Many cognitive symptoms are often generalized and erroneously used in common clinical practice. Early exposure to adverse conditions such as malnutrition, poverty, parental drug use, parental neglect, infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, and perinatal conditions such as prematurity are frequent risk factors associated with poor performance in motor coordination, language, executive functioning, and intelligence tasks, suggesting a negative impact on neurocognitive development and adaptive capacity in children with such conditions. The results of the behavioral tests were also linked to electrophysiological findings such as bilateral slowing; the presence of paroxysmal activity; low gamma power; decreased relative delta, alpha, and beta power; as well as increased theta power. On the one hand, the EEG reports address several mainly epileptiform features. However, slow bifrontal waves, a decrease in alpha and theta power, centro-parietal paroxysmal activity, abnormal background waves, and synchronous theta are commonly observed in later infants, while lower gamma power, a decrease in relative delta, and an increase in alpha and beta are reported from earlier developmental stages. Furthermore, on the other hand, basic neuropsychological assessments offer sensitive information about the cognitive performance of children and adults under rural risk living conditions.References

- Buda, A.; Dean, O.; Adams, H.R.; Mwanza-Kabaghe, S.; Potchen, M.J.; Mbewe, E.G.; Kabundula, P.P.; Mweemba, M.; Matoka, B.; Mathews, M.; et al. Neighborhood-Based Socioeconomic Determinants of Cognitive Impairment in Zambian Children with HIV: A Quantitative Geographic Information Systems Approach. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021, 10, 1071–1079.

- D’Angiulli, A.; Lipina, S.J.; Olesinska, A. Explicit and implicit issues in the developmental cognitive neuroscience of social inequality. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 254.

- Olson, L.; Chen, B.; Fishman, I. Neural correlates of socioeconomic status in early childhood: A systematic review of the literature. Child Neuropsychol. 2021, 27, 390–423.

- Tomasi, D.; Volkow, N.D. Effects of family income on brain functional connectivity in US children: Associations with cognition. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 1–8.

- Rakesh, D.; Whittle, S. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain—A systematic review of neuroimaging findings in youth. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 130, 379–407.

- Esqueda-Elizondo, J.J.; Juárez-Ramírez, R.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Galindo-Aldana, G.M.; Jiménez-Beristáin, L.; Serrano-Trujillo, A.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Inzunza-González, E. Attention Measurement of an Autism Spectrum Disorder User Using EEG Signals: A Case Study. Math. Comput. Appl. 2022, 27, 21.

- Ramírez-Arias, F.J.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Colores-Vargas, J.M.; García-Canseco, E.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; Galindo-Aldana, G.M.; Inzunza-González, E. Evaluation of Machine Learning Algorithms for Classification of EEG Signals. Technologies 2022, 10, 79.

- Wu, W.; Ma, L.; Lian, B.; Cai, W.; Zhao, X. Few-Electrode EEG from the Wearable Devices Using Domain Adaptation for Depression Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1087.

- Jan, D.; de Vega, M.; López-Pigüi, J.; Padrón, I. Applying Deep Learning on a Few EEG Electrodes during Resting State Reveals Depressive States. A Data Driven Study. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1506.

- Pfurtscheller, G.; Lopes da Silva, F.H. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: Basic principles. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 1842–1857.

- Selim, R.; Benbadis, M.; Aatif, M.; Husain, M.; Peter, W.; Kaplan, M.; William, O.; Tatum, I.V.D. Handbook of EEG Interpretation; Demos Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- Fried, S.; Moshé, S.L. Basic physiology of the EEG. Neurol. Asia 2011, 16, 23–25.

- Schomer, D.L.; Lopes da Silva, F.H. Niedermeyer’s Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017.

- Jellinger, K.A. Niedermeyer’s Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, 6th ed. In Eur. J. Neurol.; 2011; Volume 18, p. e126.

- Miley, C.E.; Forster, F.M. Activation of partial complex seizures by hyperventilation. Arch. Neurol. 1977, 34, 371–373.

- Blackstock, J.S.; Chae, K.B.; Mauk, G.W.; McDonald, A. Achieving Access to Mental Health Care for School-Aged Children in Rural Communities: A Literature Review. Rural Educ. 2018, 39, 12–25.

- Smith, S.L.; Franke, M.F.; Rusangwa, C.; Mukasakindi, H.; Nyirandagijimana, B.; Bienvenu, R.; Uwimana, E.; Uwamaliya, C.; Ndikubwimana, J.S.; Dorcas, S.; et al. Outcomes of a primary care mental health implementation program in rural Rwanda: A quasi-experimental implementation-effectiveness study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228854.

- Crichlow, M.A.; Northover, P.; Giusti-Cordero, J. Race and Rurality in the Global Economy; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2018.

- Bohem, R.; Visse, S. Book reviews. Prof. Geogr. 1986, 38, 430–457.

- Warren, J.C.; Smalley, K.B. Rural Public Health: Best Practices and Preventive Models; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014.

- Allott, K.; Lloyd, S. The provision of neuropsychological services in rural/regional settings: Professional and ethical issues. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2009, 16, 193–206.

- Costa, L.G.; Cole, T.B.; Dao, K.; Chang, Y.C.; Coburn, J.; Garrick, J.M. Effects of air pollution on the nervous system and its possible role in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 210, 107523.

- Luo, D.; Du, J.; Wang, P.; Yang, W. Urban-rural comparisons in health risk factor, health status and outcomes in Tianjin, China: A cross-sectional survey (2009–2013). Aust. J. Rural Health 2019, 27, 535–541.

- Jiménez-Ceballos, B.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Ocharan-Hernández, M.E.; Guerra-Araiza, C.; Farfán García, E.D.; Muñoz-Ramírez, U.E.; Fuentes-Venado, C.E.; Pinto-Almazán, R. Nutritional Status and Poverty Condition Are Associated with Depression in Preschoolers. Children 2023, 10, 835.

- Doyle, C.; Cicchetti, D.; Georgieff, M.K.; Tran, P.V.; Carlson, E.S. Atypical fetal development: Fetal alcohol syndrome, nutritional deprivation, teratogens, and risk for neurodevelopmental disorders and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 1063–1086.

- Smalley, K.B.; Warren, J.C.; Rainer, J. Rural Mental Health: Issues, Policies, and Best Practices; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012.

- Bell, E.; Merrick, J. Rural Child Health: International Aspects; Health and Human Development, Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- Beck, S.; Wojdyla, D.; Say, L.; Betran, A.P.; Merialdi, M.; Requejo, J.H.; Rubens, C.; Menon, R.; Van Look, P.F.A. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: A systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 31–38.

- Chattopadhyay, N.; Mitra, K. Neurodevelopmental outcome of high risk newborns discharged from special care baby units in a rural district in India. J. Public Health Res. 2015, 4, 7–12.

- Doandes, F.M.; Manea, A.M.; Lungu, N.; Brandibur, T.; Cioboata, D.; Costescu, O.C.; Zaharie, M.; Boia, M. The Role of Amplitude-Integrated Electroencephalography (aEEG) in Monitoring Infants with Neonatal Seizures and Predicting Their Neurodevelopmental Outcome. Children 2023, 10, 833.

- Galindo, G.; Solovieva, Y.; Machinskaya, R.; Quintanar, L. Atención selectiva visual en el procesamiento de letras: Un estudio comparative. OCNOS Rev. De Estud. Sobre Lect. 2016, 15, 69–80.

- Barbiero, C.; Montico, M.; Lonciari, I.; Monasta, L.; Penge, R.; Vio, C.; Tressoldi, P.E.; Carrozzi, M.; De Petris, A.; De Cagno, A.G.; et al. The lost children: The underdiagnosis of dyslexia in Italy. A cross-sectional national study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210448.

- Cainelli, E.; Vedovelli, L.; Carretti, B.; Bisiacchi, P. EEG correlates of developmental dyslexia: A systematic review. Ann. Dyslexia 2023, 73, 184–213.

- Corcino, C.O.; Teles, R.B.d.A.; Almeida, J.R.G.d.S.; Lirani, L.d.S.; Araújo, C.R.M.; Gonsalves, A.d.A.; Maia, G.L.d.A. Evaluation of the effect of pesticide use on the health of rural workers in irrigated fruit farming. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2019, 24, 3117–3128.

- Monjura, K.; Raynes-Greenow, C.; Aminur, R.; Ashraful, A. Correction: Perceptions and practices related to birthweight in rural Bangladesh: Implications for neonatal health programs in low- and middle-income settings. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229165.

- Chanchani, D. Maternal and child nutrition in rural Chhattisgarh: The role of health beliefs and practices. Anthropol. Med. 2019, 26, 142–158.

- Rohrer, J.E.; Borders, T.F.; Blanton, J. Rural residence is not a risk factor for frequent mental distress: A behavioral risk factor surveillance survey. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 46.

- Ueda, T.; Musha, T.; Asada, T.; Yagi, T. Classification Method for Mild Cognitive Impairment Based on Power Variability of EEG Using Only a Few Electrodes. Electron. Commun. Jpn. 2016, 99, 107–114.

- Agarwal, K.N.; Das, D.; Agarwal, D.K.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Mishra, S. Soft neurological signs and EEG pattern in rural malnourished children. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1989, 78, 873–878.

- Beckwith, L.; Parmelee, A.H.J. EEG patterns of preterm infants, home environment, and later IQ. Child Dev. 1986, 57, 777–789.

- Placencia, M.; Sander, J.W.; Roman, M.; Madera, A.; Crespo, F.; Cascante, S.; Shorvon, S.D. The characteristics of epilepsy in a largely untreated population in rural Ecuador. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1994, 57, 320–325.

- Cozac, V.V.; Chaturvedi, M.; Hatz, F.; Meyer, A.; Fuhr, P.; Gschwandtner, U. Increase of EEG Spectral Theta Power Indicates Higher Risk of the Development of Severe Cognitive Decline in Parkinson’s Disease after 3 Years. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 284.

- Levin, A.R.; Varcin, K.J.; O’Leary, H.M.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Nelson, C.A. EEG power at 3 months in infants at high familial risk for autism. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2017, 9, 34.

- Kanemura, H.; Sano, F.; Ohyama, T.; Mizorogi, S.; Sugita, K.; Aihara, M. EEG characteristics predict subsequent epilepsy in children with their first unprovoked seizure. Epilepsy Res. 2015, 115, 58–62.

- Ehlers, C.L.; Wall, T.L.; Garcia-Andrade, C.; Phillips, E. Effects of age and parental history of alcoholism on EEG findings in mission Indian children and adolescents. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001, 25, 672–679.

- Amores-Villalba, A.; Mateos-Mateos, R. Revisión de la neuropsicología del maltrato infantil: La neurobiología y el perfil neuropsicológico de las víctimas de abusos en la infancia. Psicol. Educ. 2017, 23, 81–88.

- Tarullo, A.R.; Obradović, J.; Keehn, B.; Rasheed, M.A.; Siyal, S.; Nelson, C.A.; Yousafzai, A.K. Gamma power in rural Pakistani children: Links to executive function and verbal ability. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 26, 1–8.

- Machinskaya, R.I.; Semenova, O.A.; Absatova, K.A.; Sugrobova, G.A. Neurophysiological factors associated with cognitive deficits in children with ADHD symptoms: EEG and neuropsychological analysis. Psychol. Neurosci. 2014, 7, 461–473.

- Semenova, O.; Machinskaya, R. The influence of the functional state of brain regulatory systems on the efficiency of voluntary regulation of cognitive activity in children: II. neuropsychological and EEG analysis of brain regulatory functions in 10–12-year-old children with learning difficulties. Hum. Physiol. 2015, 41, 478–486.

- Cottrell, J.N.; Thomas, D.S.; Mitchell, B.L.; Childress, J.E.; Dawley, D.M.; Harbrecht, L.E.; Jude, D.A.; Valentovic, M.A. Rural and urban differences in prenatal exposure to essential and toxic elements. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. Part A 2018, 81, 1214–1223.

- Thatcher, R.W.; Lester, M.L. Nutrition, environmental toxins and computerized EEG: A mini-max approach to learning disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 1985, 18, 287–297.

- Urizar, G.G.J.; Caliboso, M.; Gearhart, C.; Yim, I.S.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Process Evaluation of a Stress Management Program for Low-Income Pregnant Women: The SMART Moms/Mamás LÍSTAS Project. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 2019, 46, 930–941.

- Atif, N.; Nazir, H.; Zafar, S.; Chaudhri, R.; Atiq, M.; Mullany, L.C.; Rowther, A.A.; Malik, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Rahman, A. Development of a Psychological Intervention to Address Anxiety During Pregnancy in a Low-Income Country. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 927.

- St John, A.M.; Kao, K.; Liederman, J.; Grieve, P.G.; Tarullo, A.R. Maternal cortisol slope at 6 months predicts infant cortisol slope and EEG power at 12 months. Dev. Psychobiol. 2017, 59, 787–801.

- Blair, C.; Berry, D.J. Moderate within-person variability in cortisol is related to executive function in early childhood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 81, 88–95.

- Katus, L.; Mason, L.; Milosavljevic, B.; McCann, S.; Rozhko, M.; Moore, S.E.; Elwell, C.E.; Lloyd-Fox, S.; de Haan, M. ERP markers are associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes in 1-5 month old infants in rural Africa and the UK. NeuroImage 2020, 210, 116591.

- Mattsson, P.; Tomson, T.; Edebol Eeg-Olofsson, K.; Brännström, L.; Ringbäck Weitoft, G. Association between sociodemographic status and antiepileptic drug prescriptions in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 2149–2155.

- Kariuki, S.M.; Matuja, W.; Akpalu, A.; Kakooza-Mwesige, A.; Chabi, M.; Wagner, R.G.; Connor, M.; Chengo, E.; Ngugi, A.K.; Odhiambo, R.; et al. Clinical features, proximate causes, and consequences of active convulsive epilepsy in Africa. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 76–85.

- Chidi, I.R.; Chidi, N.A.; Ebele, A.A.; Chinyelu, O.N. Co-Morbidity of attention deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and epilepsy In children seen In University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu: Prevalence, Clinical and social correlates. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2014, 21, 273–278.

- Burton, K.J.; Rogathe, J.; Whittaker, R.; Mankad, K.; Hunter, E.; Burton, M.J.; Todd, J.; Neville, B.G.R.; Walker, R.; Newton, C.R.J.C. Epilepsy in Tanzanian children: Association with perinatal events and other risk factors. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 752–760.

- Kihara, M.; de Haan, M.; Garrashi, H.H.; Neville, B.G.R.; Newton, C.R.J.C. Atypical brain response to novelty in rural African children with a history of severe falciparum malaria. J. Neurol. Sci. 2010, 296, 88–95.

- Kihara, M.; Hogan, A.M.; Newton, C.R.; Garrashi, H.H.; Neville, B.R.; de Haan, M. Auditory and visual novelty processing in normally-developing Kenyan children. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 121, 564–576.

- Marcos-Vidal, L.; Martínez-García, M.; Pretus, C.; Garcia-Garcia, D.; Martínez, K.; Janssen, J.; Vilarroya, O.; Castellanos, F.X.; Desco, M.; Sepulcre, J.; et al. Local functional connectivity suggests functional immaturity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 2442–2454.

- Cao, Q.; Zang, Y.; Sun, L.; Sui, M.; Long, X.; Zou, Q.; Wang, Y. Abnormal neural activity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroreport 2006, 17, 1033–1036.

- Casey, B.J.; Castellanos, F.X.; Giedd, J.N.; Marsh, W.L.; Hamburger, S.D.; Schubert, A.B.; Vauss, Y.C.; Vaituzis, A.C.; Dickstein, D.P.; Sarfatti, S.E.; et al. Implication of right frontostriatal circuitry in response inhibition and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 374–383.

- Aihua, F.; Lijie, W.; Xiang, C.; Xiaoyan, L.; Ling, L.; Baozhen, W.; Huiwen, L.; Xiuting, M.; Ruoyan Gai, T. Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD): Implications for health and nutritional issues among rural children in China. BioScience Trends 2015, 9, 82–87.

More