A standardized assessment of Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) poses challenges across diverse tumor histologies, treatment modalities, and testing platforms, requiring careful consideration to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Despite clinical trials demonstrating favorable responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), not all patients with elevated TMB exhibit benefits, and certain tumors with a normal TMB may respond to ICIs. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the intricate interplay between TMB and the tumor microenvironment, as well as genomic features, is crucial to refine its predictive value. BAdvancements in bioinformatics advancements hold potential to improve the precision and cost-effectiveness of TMB assessments, addressing existing challenges.

- TMB

- tumor mutational burden

- ICI

- immune checkpoint inhibitor

1. Background

2. Challenges of Using TMB as Biomarker of Response to ICI

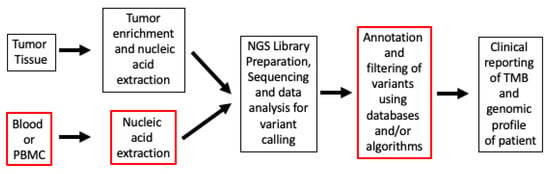

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) encompasses 32 Mb of the coding region, the entire set of 22,000 genes, which constitutes roughly 1% of the genome. WES, the gold standard for TMB calculation, measures the number of somatic alterations, whereas the FDA-authorized surrogate panel assays including the Memorial Sloan-Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets or MSK-IMPACT (468 genes) and F1CDx assay (324 genes) measure the density of somatic alterations, including target footprints of approximately 1.14 Mb and 0.8 Mb of the coding regions, respectively [12,13]. Keynote-158, the pivotal trial leading to the tissue-agnostic approval of pembrolizumab, evaluated tissue TMB (tTMB) in FFPE (Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded) tumor samples through the utilization of the F1CDx assay with a predefined criterion for classifying high tTMB as the presence of a minimum of 10 mut/Mb. The trial showed an objective response rate (ORR) of 29% in the tTMB-high versus 6% in the non-tTMB-high groups when treated with pembrolizumab at 200 mg IV (intravenously) every 3 weeks until unacceptable toxicity or disease progression [15]. The overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were secondary outcomes in the trial, and a mOS (median OS) benefit was not seen (11.5 months in t-TMB-high versus 12.8 months in non-tTMB-high group). The trial was certainly limited in the types of cancers (it included nine different cancer types) and patient numbers, including cancers with relative resistance to immunotherapy. Fourteen percent of patients assessed for efficacy in the TMB-high group also had Microsatellite Instability-High (MSI-H); however, after excluding patients with missing or MSI-H status, the ORR was 28%. A retrospective analysis of several keynote trials (Keynote-001, Keynote-002, Keynote-010, Keynote-012, Keynote-028, Keynote-045, Keynote-055, Keynote-059, Keynote-061, Keynote-086, Keynote-100) demonstrated improvement in ORR among patients treated with ICI, with tTMB ≥ 175 mutations/exome compared to TMB < 175 mutations/exome (31.4% vs. 9.5%, respectively). Additionally, an analysis of patients in Keynote-010, Keynote-045, and Keynote-061 showed improvements in PFS and OS compared to chemotherapy [18]. A more recent retrospective analysis also showed that patients in Keynote-042 derived PFS and OS benefits if their tTMB was ≥ 175 mutations/exome compared to tTMB < 175 mutations/exome [19]. Multiple other systematic reviews and metanalyses have indicated a strong association between high TMB and enhanced efficacy, with several studies also highlighting improved survival outcomes across cancers and in specific cancer types [20,21,22]. When it comes to evaluating TMB, inherent differences exist in testing workflow methods (Figure 1).