You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Meijing Wang.

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapy is one of the most promising modalities for cardiac repair. Accumulated evidence suggests that the therapeutic value of MSCs is mainly attributable to exosomes. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) replicate the beneficial effects of MSCs by regulating various cellular responses and signaling pathways implicated in cardiac regeneration and repair. miRNAs constitute an important fraction of exosome content and are key contributors to the biological function of MSC-Exo.

- mesenchymal stem cells

- microRNA

- cardiac regeneration

1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapy is one of the most promising modalities for cardiac repair and regeneration. Accumulated evidence from clinical trials have demonstrated its safety, practicality, and potential effectiveness for treatment of ischemic heart disease [1,2,3,4][1][2][3][4]. The findings from ourthe group and others have revealed that MSC paracrine action is the primary mechanism mediating tissue protection against ischemia [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. However, poor survival, limited homing, and insufficient engraftment of implanted MSCs greatly hamper a better prognosis.

Of note, emerging studies provide evidence that MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) emulate MSC secretome-mediated cardiac repair [13]. Indeed, MSC-Exos function as regulators of MSC-mediated paracrine protection by transporting miRNAs (miRNA or miR), messenger RNAs, and proteins to target cells [13]. Among these, miRNA is a key functional form in exosomes to deliver regulatory information, thus impacting the physiology of recipient cells. miRNAs constitute an important fraction of exosome content and are key contributors to the biological function of exosomes [14,15,16][14][15][16]. MSC-Exos carrying specific miRNAs have been reported to mediate cardiac repair and regeneration after myocardial infarction (MI), encouraging angiogenesis and cell proliferation, while reducing apoptosis and inflammation in the ischemic heart. Therefore, the MSC-Exo serves as a potential therapeutic while circumventing the risks and disadvantages associated with cell therapies.

MI remains the leading cause of heart failure and death worldwide. Myocardial ischemia, leading to myocardial dysfunction and infarction, is responsible for the irreversible loss of functional cardiomyocytes. Therapeutic prevention of myocyte loss in infarcted myocardium potentially through cardiac regeneration is therefore valuable and a topic of well-deserved attention in research [17].

2. Biological Functions of MSC Exosomal miRNAs in Heart Repair

2.1. Cell Proliferation and Anti-Apoptosis

MSC secreted products have been well established to be cardioprotective in contexts of MI and heart failure [62][18]. Besides paracrine protection, evidence supports that MSC-derived factors improve outcomes of cardiac lineage differentiation, angiogenesis, anti-fibrotic healing, anti-inflammation, and immune modulation in damaged cardiac tissue [63,64][19][20]. Particularly, MSC-Exo cargos have been shown to decrease apoptosis, repair the damaged cardiomyocytes, increase cardiomyocyte proliferation, and promote re-entry into the cell cycle. A systems level analysis conducted by Ferguson et al. details the various biological effects of MSC exosomal miRNAs [28][21]. Considering its effect on the induction of proliferation in cardiomyocytes, miR-199a-3p is a particularly important miRNA included in the analysis. miR-199a is predicted to target 22 genes implicated in the regulation of cell death, proliferation, and cell cycle [28][21], which highlights the importance of miR-199a in supporting cell growth. Indeed, miR-199a-3p plays a key role in cardiomyocyte survival via activation of Akt survival pathway following simulated ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) in vitro using neonatal rat and adult mouse cardiomyocytes [65][22]. miR-199a-3p has also been determined to be one of few miRNAs crucial to the induction of cardiac regeneration [66][23]. OurThe study further reveals that miR-199a-3p is abundant in MSC-Exo and benefits cell survival in the heart following I/R [35][24]. miR-199a targets Crim1, a gene essential to the inhibition of cardiomyocyte proliferation [66][23], and has been found to increase cardiomyocyte proliferation by 30% [66][23]. Treatment with miR-199a-3p increases the percentage of EdU+ cardiomyocytes, associated with upregulated levels of cyclin genes in 7-day-old and adult rat cardiomyocytes ex vivo [66][23]. Similarly, MSC-Exo loaded with miR-199a significantly promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation as shown by increased EdU+ cardiomyocytes (from 18-day-old mouse hearts) in ex vivo culture and inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis through reduction in BAX expression [28][21]. Yet, p53 is another notable gene, the activity of which is altered by miRNA-199-3p. Additionally, p53 is intimately implicated in regulating apoptosis in a variety of mammalian cells including cardiomyocytes [67][25]. Upregulated p53 levels are related to increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis [68,69][26][27]. MSC exosomal miRNA-199a targets p53 to decrease expression of NF-κB and caspase-9, thus reducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis [28][21]. Additional evidence suggests that miR-199a-3p can target CABLES1 to mediate p53 suppression [70][28]. Of note, miR-199a is predicted to target retinoblastoma (RB1) (potentially regulating cell cycle arrest via RB1) [71][29], LKB1 for cell proliferation [72][30], and NEUROD1 for cell cycle arrest [73][31]. Collectively, these studies suggest that miR-199a can regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle phases through multiple signaling pathways. miR-21 is another cardio beneficial miRNA enriched in MSC-Exo. On the one hand, miR2-21-5p acts through PI3K to increase gene expression of calcium handling genes hECT, LTCC, and SERCA2, thus improving cardiac tissue contractility [74][32]. On the other hand, miR2-21-5p decreases BAX/BCL2 ratio, an indication of antiapoptotic activity and downregulates pro-apoptotic gene products PDCD4, PTEN, Peli1, and FasL, thereby conveying anti-apoptotic effects for cardiac repair [75,76][33][34]. miR-21a-5p in MSC-Exo cargo also acts as a major cardioprotective paracrine factor to mediate cardiac repair via control of PTEN-regulated apoptotic signaling [75][33]. Emerging evidence has demonstrated that MSC exosomal miRNAs improve cardiomyocyte survival via multiple signaling pathways. MSC-Exo miR-22 exerts anti-apoptotic effects through directly targeting methyl CpG binding protein 2 (Mecp2) [77][35]. miR-25-3p in MSC-Exo improves the viability of adult mouse cardiomyocytes that underwent oxygen-glucose deprivation in vitro and decreases apoptosis in mouse I/R hearts in vivo via reduction in FASL/PTEN pathway [78][36]. Overexpression of miR-30e in MSC-Exo significantly reduces infarct size, cardiac injury, and apoptosis, thus leading to improved cardiac function in the rat MI model [79][37]. MSC-Exo delivers miR-30e to increase cell proliferation (demonstrated by enhanced EdU+ cells) and downregulate the number of apoptotic cells in oxygen-glucose deprived H9c2 cells via the LOX1/NF-κB p65/caspase-9 axis [79][37]. miR-125b mediates cardio protection of MSC-Exo through modulating p53-Bnip3 signaling to reduce autophagic flux and cell death in hypoxia and serum starved neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes [80][38], while the exosomes from MSCs pretreated with the anti-miR-125b oligonucleotide have less benefit with larger infarct size and worsened cardiac function compared to the MSC-Exo group in a mouse MI model [80][38]. The expression of p53 was also downregulated by miR-221 from engineered MSCs. MSC-EV containing miR-221 significantly decreases neonatal rat ventricle cardiomyocyte apoptosis through reducing p53 and p53-upregulated PUMA [20][39]. Exosomal miR-221-3p from young MSCs further inhibits cardiomyocyte (H9c2 cells) apoptosis in vitro under hypoxia and serum deprivation and reduces myocardial apoptosis with improved cardiac function via the PTEN/Akt pathway in a rat MI model [81][40]. miR-205 is found to decrease cardiomyocyte apoptosis in neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia [82][41]. Overexpressing miR-338 in MSC-Exo ameliorates cell death in H2O2-stressed H9c2 cells and improves cardiac function in a rat MI model via decreasing BAX/BCL2 [83][42]. Moreover, miR-1246 mitigates hypoxia-induced cell death in H9c2 cells following oxygen and glucose deprivation ex vivo and decreases cardiac tissue damage in a rat LAD (left anterior descending coronary) ligation model through targeting serine protease 23 (PRSS23) and down-activating the Snail/alpha-smooth muscle actin signaling [84][43]. Interestingly, MSC-Exo delivers miR-182-5p to reduce cell pyroptosis in neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes under hypoxia and in mouse I/R hearts via downregulation of gasdermin D [85][44]. The morbidity and mortality of cardiac damage stems from the inability of adult cardiac tissue to proliferate in order to adequately replace the damaged tissue. Rather than cell proliferation, cardiac cells mainly undergo hypertrophy to adapt to cardiac demands [86][45]. Repression of cell cycle activators and expression of cell cycle inhibitors contribute to maintenance of cardiac cells in the resting phase of the cell cycle. However, manipulation of the cell cycle can re-engage myocardial cells that have exited the cell cycle to enact cell division [87][46]. Environmental oxygen, e.g., hypoxia, has been shown to regulate postnatal cardiomyocyte cell cycle re-entry, as indicated by increased levels of p-histone H3 (a marker for G2-M progression) and Aurora B kinase at the cleavage furrow (a marker for cytokinesis) [87][46]. Once again, miRNAs can be used to manipulate gene expression in cardiomyocytes. miR-590-3p and miR-199a-3p effectively increase cardiomyocyte proliferation in vitro [66][23]. miR-294 overexpression has also been shown to stimulate cell cycle activity in cardiomyocytes through the Wee1 pathway [88][47]. Increased expression of Ki67, p-histone H3, and Aurora B kinase has been noted in neonatal rodent ventricular myocytes treated with miR-294 [88][47]. While other miRNAs also promote cardiomyocyte proliferation, miR-590-3p and miR-199a-3p conduct this without simultaneously inducing hypertrophy. Translation to in vivo models further validates the proliferative effect of miR-590-3p and miR-199a-3p. DNA synthesis and present mitotic figures confirm the role of these miRNAs to encourage re-entry into the cell cycle [66][23]. In vivo and in vitro models have provided evidence of the efficacy of exosomes in apoptotic resistance and cardiac healing. miRNAs have been shown to be central to the function of exosomes. An extensive review by [89][48] provides a collection of the cardioprotective effects of at least 12 miRNAs compiled from data published by more than 15 studies. miRNA activity in altering various cellular pathways further supports their values in cardiac repair and regeneration. Though the presented pathways through which various miRNAs act are not shared completely, some overlap signaling pathways exist, and synergistic effects may further potentiate the therapeutic effects of the miRNAs in MSC-Exo.2.2. Angiogenic Effects on the Injured Heart

Analysis of MSC exosome properties contributing to cardioprotective effects reiterates the importance of miRNAs. Exosome miRNAs are mainstays in repairing damaged heart tissue following injury [90][49]. MSC-Exo contains many miRNAs predicted to regulate regenerative target mRNAs. Specifically, MSC-Exo miRNAs have been found to promote angiogenesis in the heart. miRNA profiling and bioinformatics have revealed that the top 23 miRNAs constitute 79.1% of the exosomal miRNA content from human BM-MSCs. Among them, miR-23a-3p and miR-130a-3p target the greatest number of genes related to angiogenesis and vascular development [28][21]. miR-130a-3p has been shown to downregulate anti-angiogenic homeobox genes GAX and HOXA5, thus inducing angiogenic effects [91][50]. Only modified MSC-Exo with specific enrichment of miR-130a-3p, as opposed to unmodified MSC-Exo, leads to a capillary-like network of tubular structures in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [28][21]. Human UC-MSC-Exo also promotes endothelial network formation by delivering miR-23a-3p to activate phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)/Akt signaling [21][51]. Similarly, through the PTEN/Akt pathway, human MSC exosomal miR-21 is identified to facilitate angiogenesis in a rat model of MI [76][34]. The involvement of miR-126-enriched exosomes is found to significantly promote angiogenesis, resulting in increased density of WF-containing cells indicative of vascular endothelium along the infarct border. Administration of the exosomes also displayed a dose-dependent relationship in the promotion of angiogenesis, with miR-126 enriched exosomes inducing greater epithelial progenitor cell migration and tube-like structure formation in hypoxic conditions than was observed in either regular MSC-Exo or control treatments [92][52]. The entities of specific exosomal miRNAs reported to promote cardiac repair through angiogenesis vary between different studies. This is to be expected due to the vast number of miRNAs included in endosomes and the great variability in potential downstream effects for each miRNA. A current study reports that the benefits of AD-MSC-Exo in migration of microvascular endothelial cells and angiogenesis are abolished with administration of an miRNA-205 inhibitor in a murine MI model [82][41]. In addition, human UC-MSC exosomal miR-1246 has been noted to increase angiogenesis in HUEVCs by targeting serine protease 23 and reducing activation of the Snail/alpha-smooth muscle actin pathway [84][43]. miR-210 abundantly detected in mouse BM-MSC-Exo is shown to downregulate Efna3, thus improving tubulogenesis in vitro and enhancing neoangiogenesis with more capillaries in peri-infarct regions in post-MI mouse hearts [93][53]. Intramyocardial injection of MSC-Exo loaded with miR-132 significantly increases neovascularization in the peri-infarct zone and preserves heart function in a murine MI model [94][54]. MSC exosomal miR-30b has been found to promote HUVEC tube-like structure formation using the loss and gain function approach [95][55]. Finally, miR-223-5p is identified as an effective candidate in TSA-pretreated MSC-Exo to mediate cardio protection through enhanced angiogenesis and inhibited CCR2 activation to reduce monocyte infiltration [96][56]. These are a few of the likely numerous miRNAs included in MSC-Exo with cardiac reparative properties through angiogenesis. The abundance of miRNAs shown to benefit cardiac repair is a good omen for therapeutics, as loading specific miRNAs in MSC-Exo can be investigated to yield optimal combinations to activate synergistic mechanisms and pathways.2.3. Anti-Fibrosis and Anti-Inflammation

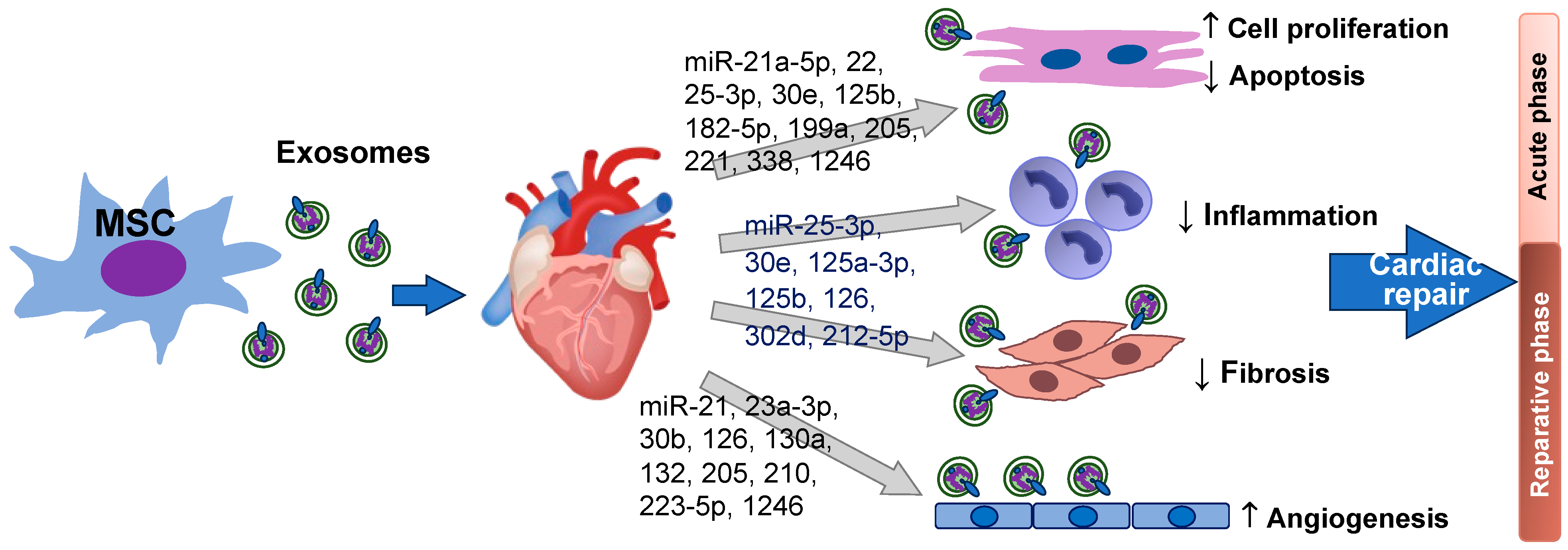

Fibrosis is the excessive formation of fibrous connective tissue, often as a result of chronic inflammation. Following MI, fibrosis contributes to adverse remodeling of the heart. Excessive fibrosis can impair the structure and function of the heart. Studies [28,97,98][21][57][58] have indicated that MSC-Exo is able to ameliorate cardiac fibrosis and limit adverse ventricular remodeling after MI by modulating the activity of fibroblasts and downregulating pro-fibrotic signals to reduce the production of extracellular matrix proteins, thus preventing the formation of excessive scar tissue. Inflammation following MI can increase deposition of extracellular collagen as well, leading to scar formation. Microparticle engineered inhibition of MSC pro-inflammatory secretome has been reported to reduce collagen deposition in human and murine cardiac fibroblasts [99][59]. Improving cardiac regeneration while limiting scar formation is important to long term cardiac repair. MSC-Exo containing different miRNAs may regulate fibrotic pathways and promote tissue repair through different pathways, including suppression of inflammation and cell death, and improvement of angiogenesis. It is reported that miR-125a-3p is enriched in MSC-Exo and plays an important role in MSC-Exo elicited cardio protection, as shown by the increasing cardiac function and limiting adverse remodeling in mouse I/R hearts [100][60]. miR-125a-3p is considered to target Tgfbr1, Klf13, and Daam1 to regulate the function of fibroblasts, macrophages, and endothelial cells, thus reducing fibroblast proliferation and activation, promoting M2 macrophage polarization to attenuate inflammation, and facilitating angiogenesis [100][60]. miR-126 is also found to reduce production of inflammatory cytokines, enhance VEGF, and decrease pro-fibrotic gene expression to mitigate adverse myocardial remodeling post MI in murine models [55,92][52][61]. Of note, the same exosomal miRNA could regulate different processes for cardiac repair attributable to the complex mechanism of action and different variables of the comprehensive effects. Through anti-apoptotic effects, MSC-Exo with increased miR-22 content has been shown to significantly reduce cardiac fibrosis compared to MSC-Exo with inhibition of miR-22 in a mouse MI model [77][35]. Also, AD-MSC exosomal miR-205 markedly decreases cardiac fibrosis via promoted angiogenesis and attenuated cardiomyocyte apoptosis [82][41]. miR-25-3p containing MSC-Exo is found to suppress expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in oxygen-glucose deprivation stressed adult mouse cardiomyocytes and in mouse I/R hearts via inhibition of EZH2 (enhancer of zest homologue 2)/SOCS3 axis [78][36]. Overexpressing miR-30e in MSC-Exo significantly decreases the level of fibrosis and suppresses MI-induced inflammation as shown by the increased anti-inflammatory factor CD206 in the rat infarcted myocardium in vivo [79][37]. MSC-EV-delivered miR-302d-3p diminishes inflammation, reduces myocardial fibrosis, and decreases apoptosis in the infarcted area through repressing the NFκB pathway-related MD2 and BCL6 levels [101][62]. Furthermore, miR-212-5p enriched MSC-EVs have been reported to reduce the levels of α-SMA, Collagen I, TGF-β1, and IL-1β in cardiac fibroblasts in vitro, attenuating cardiac fibrosis via inhibiting the NLRC5/VEGF/TGF-β1/SMAD axis [102][63]. Collectively, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of MSC exosomal miRNAs promote a more favorable microenvironment for tissue repair and prevent further damage in the heart during the acute phase of MI. Meanwhile, pro-angiogenic and anti-fibrotic activities of MSC exosomal miRNAs promote blood vessel formation to increase blood supply for delivery of oxygen and nutrients, thereby supporting tissue repair and regeneration in the reparative phase. Figure 1 summarizes MSC exosomal miRNAs in cardiomyocyte proliferation/survival, anti-inflammation, anti-fibrosis, and angiogenesis during cardiac repair after heart injury.

Figure 1. miRNAs derived from MSC exosomes improve cardiomyocyte survival/proliferation, promote angiogenesis, suppress inflammation, and reduce cardiac fibrosis in the heart after injury. Except the heart image from Heart Research Institute, this figure is created by the authors using PowerPoint.

References

- Chullikana, A.; Majumdar, A.S.; Gottipamula, S.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Kumar, A.S.; Prakash, V.S.; Gupta, P.K. Randomized, double-blind, phase I/II study of intravenous allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells in acute myocardial infarction. Cytotherapy 2015, 17, 250–261.

- Suncion, V.Y.; Ghersin, E.; Fishman, J.E.; Zambrano, J.P.; Karantalis, V.; Mandel, N.; Nelson, K.H.; Gerstenblith, G.; DiFede Velazquez, D.L.; Breton, E.; et al. Does transendocardial injection of mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial function locally or globally?: An analysis from the Percutaneous Stem Cell Injection Delivery Effects on Neomyogenesis (POSEIDON) randomized trial. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1292–1301.

- Heldman, A.W.; DiFede, D.L.; Fishman, J.E.; Zambrano, J.P.; Trachtenberg, B.H.; Karantalis, V.; Mushtaq, M.; Williams, A.R.; Suncion, V.Y.; McNiece, I.K.; et al. Transendocardial mesenchymal stem cells and mononuclear bone marrow cells for ischemic cardiomyopathy: The TAC-HFT randomized trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 62–73.

- Rodrigo, S.F.; van Ramshorst, J.; Hoogslag, G.E.; Boden, H.; Velders, M.A.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Roelofs, H.; Al Younis, I.; Dibbets-Schneider, P.; Fibbe, W.E.; et al. Intramyocardial injection of autologous bone marrow-derived ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells in acute myocardial infarction patients is feasible and safe up to 5 years of follow-up. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2013, 6, 816–825.

- Wang, M.; Tan, J.; Wang, Y.; Meldrum, K.K.; Dinarello, C.A.; Meldrum, D.R. IL-18 binding protein-expressing mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial protection after ischemia or infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17499–17504.

- Wang, M.; Tsai, B.M.; Crisostomo, P.R.; Meldrum, D.R. Pretreatment with adult progenitor cells improves recovery and decreases native myocardial proinflammatory signaling after ischemia. Shock 2006, 25, 454–459.

- Wei, X.; Du, Z.; Zhao, L.; Feng, D.; Wei, G.; He, Y.; Tan, J.; Lee, W.H.; Hampel, H.; Dodel, R.; et al. IFATS collection: The conditioned media of adipose stromal cells protect against hypoxia-ischemia-induced brain damage in neonatal rats. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 478–488.

- Cai, L.; Johnstone, B.H.; Cook, T.G.; Liang, Z.; Traktuev, D.; Cornetta, K.; Ingram, D.A.; Rosen, E.D.; March, K.L. Suppression of hepatocyte growth factor production impairs the ability of adipose-derived stem cells to promote ischemic tissue revascularization. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 3234–3243.

- Wang, M.; Crisostomo, P.R.; Herring, C.; Meldrum, K.K.; Meldrum, D.R. Human progenitor cells from bone marrow or adipose tissue produce VEGF, HGF, and IGF-I in response to TNF by a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 291, R880–R884.

- Rehman, J.; Traktuev, D.; Li, J.; Merfeld-Clauss, S.; Temm-Grove, C.J.; Bovenkerk, J.E.; Pell, C.L.; Johnstone, B.H.; Considine, R.V.; March, K.L. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation 2004, 109, 1292–1298.

- Gnecchi, M.; He, H.; Liang, O.D.; Melo, L.G.; Morello, F.; Mu, H.; Noiseux, N.; Zhang, L.; Pratt, R.E.; Ingwall, J.S.; et al. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 367–368.

- Wang, M.; Tan, J.; Coffey, A.; Fehrenbacher, J.; Weil, B.R.; Meldrum, D.R. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-stimulated hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha mediates estrogen receptor-alpha-induced mesenchymal stem cell vascular endothelial growth factor production. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 138, 163–171.e1.

- Shao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, P.; Meng, Q.; Geng, Y.J.; Yu, X.Y.; et al. MiRNA-Sequence Indicates That Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes Have Similar Mechanism to Enhance Cardiac Repair. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4150705.

- Lai, R.C.; Arslan, F.; Lee, M.M.; Sze, N.S.; Choo, A.; Chen, T.S.; Salto-Tellez, M.; Timmers, L.; Lee, C.N.; El Oakley, R.M.; et al. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010, 4, 214–222.

- Baglio, S.R.; Pegtel, D.M.; Baldini, N. Mesenchymal stem cell secreted vesicles provide novel opportunities in (stem) cell-free therapy. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 359.

- Eirin, A.; Riester, S.M.; Zhu, X.Y.; Tang, H.; Evans, J.M.; O’Brien, D.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Lerman, L.O. MicroRNA and mRNA cargo of extracellular vesicles from porcine adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Gene 2014, 551, 55–64.

- Mohsin, S.; Siddiqi, S.; Collins, B.; Sussman, M.A. Empowering adult stem cells for myocardial regeneration. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 1415–1428.

- Öztürk, S.; Elçin, Y.M. Cardiac Stem Cell Characteristics in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 3101–3112.

- Öztürk, S.; Elçin, A.E.; Elçin, Y.M. Functions of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cardiac Repair. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1312, 39–50.

- Gallina, C.; Turinetto, V.; Giachino, C. A New Paradigm in Cardiac Regeneration: The Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 2015, 765846.

- Ferguson, S.W.; Wang, J.; Lee, C.J.; Liu, M.; Neelamegham, S.; Canty, J.M.; Nguyen, J. The microRNA regulatory landscape of MSC-derived exosomes: A systems view. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1419.

- Park, K.M.; Teoh, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Broskova, Z.; Bayoumi, A.S.; Tang, Y.; Su, H.; Weintraub, N.L.; Kim, I.M. Carvedilol-responsive microRNAs, miR-199a-3p and -214 protect cardiomyocytes from simulated ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. 2016, 311, H371–H383.

- Eulalio, A.; Mano, M.; Dal Ferro, M.; Zentilin, L.; Sinagra, G.; Zacchigna, S.; Giacca, M. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature 2012, 492, 376–381.

- Scott, S.R.; March, K.L.; Wang, I.W.; Singh, K.; Liu, J.; Turrentine, M.; Sen, C.K.; Wang, M. Bone marrow- or adipose-mesenchymal stromal cell secretome preserves myocardial transcriptome profile and ameliorates cardiac damage following ex vivo cold storage. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2022, 164, 1–12.

- Vaseva, A.V.; Moll, U.M. The mitochondrial p53 pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 414–420.

- Ikeda, S.; Hamada, M.; Hiwada, K. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis with enhanced expression of P53 and Bax in right ventricle after pulmonary arterial banding. Life Sci. 1999, 65, 925–933.

- Xie, Z.; Koyama, T.; Abe, K.; Fuji, Y.; Sawa, H.; Nagtashima, K. Upregulation of P53 protein in rat heart subjected to a transient occlusion of the coronary artery followed by reperfusion. Jpn. J. Physiol. 2000, 50, 159–162.

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cui, J.; Sun, M.; Pu, Z.; Wang, C.; Du, W.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Hou, J.; et al. miR199a-3p regulates P53 by targeting CABLES1 in mouse cardiac c-kit(+) cells to promote proliferation and inhibit apoptosis through a negative feedback loop. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 127.

- Sdek, P.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Y.; Huang, C.J.; Ko, C.Y.; Butler, P.C.; Weiss, J.N.; Maclellan, W.R. Rb and p130 control cell cycle gene silencing to maintain the postmitotic phenotype in cardiac myocytes. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 407–423.

- Boudeau, J.; Sapkota, G.; Alessi, D.R. LKB1, a protein kinase regulating cell proliferation and polarity. FEBS Lett. 2003, 546, 159–165.

- Mutoh, H.; Naya, F.J.; Tsai, M.J.; Leiter, A.B. The basic helix-loop-helix protein BETA2 interacts with p300 to coordinate differentiation of secretin-expressing enteroendocrine cells. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 820–830.

- Mayourian, J.; Ceholski, D.K.; Gorski, P.A.; Mathiyalagan, P.; Murphy, J.F.; Salazar, S.I.; Stillitano, F.; Hare, J.M.; Sahoo, S.; Hajjar, R.J.; et al. Exosomal microRNA-21-5p Mediates Mesenchymal Stem Cell Paracrine Effects on Human Cardiac Tissue Contractility. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 933–944.

- Luther, K.M.; Haar, L.; McGuinness, M.; Wang, Y.; Lynch Iv, T.L.; Phan, A.; Song, Y.; Shen, Z.; Gardner, G.; Kuffel, G.; et al. Exosomal miR-21a-5p mediates cardioprotection by mesenchymal stem cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 119, 125–137.

- Wang, K.; Jiang, Z.; Webster, K.A.; Chen, J.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; et al. Enhanced Cardioprotection by Human Endometrium Mesenchymal Stem Cells Driven by Exosomal MicroRNA-21. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 209–222.

- Feng, Y.; Huang, W.; Wani, M.; Yu, X.; Ashraf, M. Ischemic preconditioning potentiates the protective effect of stem cells through secretion of exosomes by targeting Mecp2 via miR-22. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88685.

- Peng, Y.; Zhao, J.L.; Peng, Z.Y.; Xu, W.F.; Yu, G.L. Exosomal miR-25-3p from mesenchymal stem cells alleviates myocardial infarction by targeting pro-apoptotic proteins and EZH2. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 317.

- Pu, L.; Kong, X.; Li, H.; He, X. Exosomes released from mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing microRNA-30e ameliorate heart failure in rats with myocardial infarction. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 4007–4025.

- Xiao, C.; Wang, K.; Xu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, Q.; Zhu, D.; et al. Transplanted Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reduce Autophagic Flux in Infarcted Hearts via the Exosomal Transfer of miR-125b. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 564–578.

- Yu, B.; Gong, M.; Wang, Y.; Millard, R.W.; Pasha, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ashraf, M.; Xu, M. Cardiomyocyte protection by GATA-4 gene engineered mesenchymal stem cells is partially mediated by translocation of miR-221 in microvesicles. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73304.

- Sun, L.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, F. Down-Regulated Exosomal MicroRNA-221—3p Derived From Senescent Mesenchymal Stem Cells Impairs Heart Repair. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 263.

- Wang, T.; Li, T.; Niu, X.; Hu, L.; Cheng, J.; Guo, D.; Ren, H.; Zhao, R.; Ji, Z.; Liu, P.; et al. ADSC-derived exosomes attenuate myocardial infarction injury by promoting miR-205-mediated cardiac angiogenesis. Biol. Direct 2023, 18, 6.

- Fu, D.L.; Jiang, H.; Li, C.Y.; Gao, T.; Liu, M.R.; Li, H.W. MicroRNA-338 in MSCs-derived exosomes inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis in myocardial infarction. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 10107–10117.

- Wang, Z.; Gao, D.; Wang, S.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W. Exosomal microRNA-1246 from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells potentiates myocardial angiogenesis in chronic heart failure. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 2211–2225.

- Yue, R.; Lu, S.; Luo, Y.; Zeng, J.; Liang, H.; Qin, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Pu, J.; Hu, H. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal microRNA-182-5p alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeting GSDMD in mice. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 202.

- Yutzey, K.E. Cardiomyocyte Proliferation: Teaching an Old Dogma New Tricks. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 627–629.

- Puente, B.N.; Kimura, W.; Muralidhar, S.A.; Moon, J.; Amatruda, J.F.; Phelps, K.L.; Grinsfelder, D.; Rothermel, B.A.; Chen, R.; Garcia, J.A.; et al. The oxygen-rich postnatal environment induces cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest through DNA damage response. Cell 2014, 157, 565–579.

- Borden, A.; Kurian, J.; Nickoloff, E.; Yang, Y.; Troupes, C.D.; Ibetti, J.; Lucchese, A.M.; Gao, E.; Mohsin, S.; Koch, W.J.; et al. Transient Introduction of miR-294 in the Heart Promotes Cardiomyocyte Cell Cycle Reentry After Injury. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, 14–25.

- Ouyang, Z.; Wei, K. miRNA in cardiac development and regeneration. Cell Regen. 2021, 10, 14.

- Woodall, B.P.; Gustafsson, Å.B. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Mediated Autophagy Inhibition. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 518–520.

- Chen, Y.; Gorski, D.H. Regulation of angiogenesis through a microRNA (miR-130a) that down-regulates antiangiogenic homeobox genes GAX and HOXA5. Blood 2008, 111, 1217–1226.

- Hu, H.; Zhang, H.; Bu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lv, F.; Pan, M.; Huang, X.; Cheng, L. Small Extracellular Vesicles Released from Bioglass/Hydrogel Scaffold Promote Vascularized Bone Regeneration by Transferring miR-23a-3p. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 6201–6220.

- Luo, Q.; Guo, D.; Liu, G.; Chen, G.; Hang, M.; Jin, M. Exosomes from MiR-126-Overexpressing Adscs Are Therapeutic in Relieving Acute Myocardial Ischaemic Injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 2105–2116.

- Wang, N.; Chen, C.; Yang, D.; Liao, Q.; Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Zeng, C.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles, via miR-210, improve infarcted cardiac function by promotion of angiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 2085–2092.

- Ma, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Meng, Q.; Sun, J.; Shao, L.; Yu, Y.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-132, Delivered by Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes, Promote Angiogenesis in Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 3290372.

- Gong, M.; Yu, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Paul, C.; Millard, R.W.; Xiao, D.S.; Ashraf, M.; Xu, M. Mesenchymal stem cells release exosomes that transfer miRNAs to endothelial cells and promote angiogenesis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 45200–45212.

- Li, S.; Yang, K.; Cao, W.; Guo, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Fan, A.; Huang, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, L.; et al. Tanshinone IIA enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via up-regulating miR-223-5p. J. Control Release 2023, 358, 13–26.

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Xie, L.; Zhao, Z.A.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Lei, W.; Shen, Z. MicroRNA-133 overexpression promotes the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells on acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 268.

- Wen, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, T. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for post-myocardial infarction cardiac repair: microRNAs as novel regulators. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 657–671.

- Ranganath, S.H.; Tong, Z.; Levy, O.; Martyn, K.; Karp, J.M.; Inamdar, M.S. Controlled Inhibition of the Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Pro-inflammatory Secretome via Microparticle Engineering. Stem Cell Rep. 2016, 6, 926–939.

- Gao, L.; Qiu, F.; Cao, H.; Li, H.; Dai, G.; Ma, T.; Gong, Y.; Luo, W.; Zhu, D.; Qiu, Z.; et al. Therapeutic delivery of microRNA-125a-5p oligonucleotides improves recovery from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice and swine. Theranostics 2023, 13, 685–703.

- Zhu, L.P.; Tian, T.; Wang, J.Y.; He, J.N.; Chen, T.; Pan, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.X.; Qiu, X.T.; Li, C.C.; et al. Hypoxia-elicited mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitates cardiac repair through miR-125b-mediated prevention of cell death in myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2018, 8, 6163–6177.

- Liu, Y.; Guan, R.; Yan, J.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, S.; Qu, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-Shuttled microRNA-302d-3p Represses Inflammation and Cardiac Remodeling Following Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2022, 15, 754–771.

- Wu, Y.; Peng, W.; Fang, M.; Wu, M.; Wu, M. MSCs-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Carrying miR-212-5p Alleviate Myocardial Infarction-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis via NLRC5/VEGF/TGF-beta1/SMAD Axis. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2022, 15, 302–316.

More