Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Zhidong Liu and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

Chronic wounds are a major health challenge that require new treatment strategies. Hydrogels are promising drug delivery systems for chronic wound healing because of their biocompatibility, hydration, and flexibility. However, conventional hydrogels cannot adapt to the dynamic and complex wound environment, which involves low pH, high levels of reactive oxygen species, and specific enzyme expression. Therefore, smart responsive hydrogels that can sense and respond to these stimuli are needed.

- smart responsive hydrogel

- chronic wound healing

- drug delivery system

1. pH-Responsive Gels

1.1. pH-Responsive Design

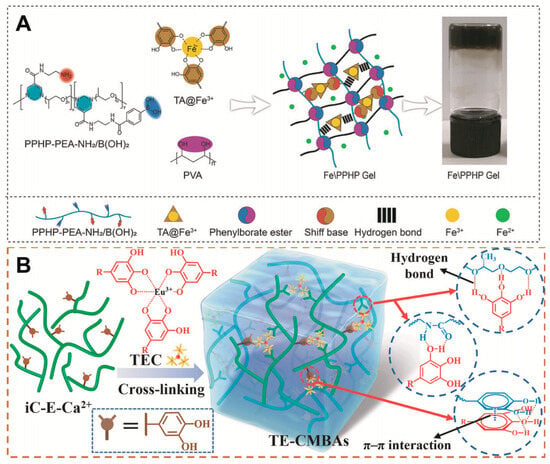

Changes in pH are typical of chronic wounds. Therefore, one of the most common types of hydrogels used in chronic wound care are those designed for acidic environments. There are several ways to construct pH-responsive hydrogels. One is to use hydrogels that contain bonds that break within a certain pH range (Figure 12A). Typically, these bonds are stable at physiological pH but hydrolysed under weakly acidic conditions. The second approach is the use of pH-sensitive polymeric materials. Most of these polymeric materials are polyelectrolytes, the pKa of which is within the physiological pH range [1][48]. In addition, pH-responsiveness can be achieved using acid-catalysed hydrolysis [2][3][49,50], nanoparticles [4][51], and electrostatic interactions [5][45].

1.2. Schiff Bases

Schiff bases form reversible imine bonds, which impart smart response properties to hydrogels in acidic environments [6][7][52,53]. The flexibility and versatility of Schiff bases make them important for chemical and biological research [8][9][54,55]. Further, there is a wide degree of flexibility for the selection of different carbonyl compounds for reaction with different amines [10][56], and it is relatively easy to introduce amino or aldehyde groups into polymeric compounds via chemical modification [1][11][48,57]. Crucially, Schiff bases can coordinate with metal ions via the hybrid orbitals of their nitrogen atoms and lone pairs to form metal complexes with different stabilities and functions [12][58], and some such ligands and their complexes have shown good antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and other biological activity [13][14][15][59,60,61].

The structural and functional characteristics of aldehydes and amines are key to the formation of Schiff bases [16][62]. For example, chitosan (CS) contains amino and hydroxyl groups and provides a rich backbone that can be chemically modified for various purposes [17][63]. Further, CS is inexpensive and readily available [18][19][64,65]. However, modified chitosan has better antibacterial and free radical scavenging ability than pristine CS [20][21][22][66,67,68]. Therefore, CS and its derivatives are often used as monomers in pH-responsive hydrogels. For example, Fang et al. reported a novel multi-functional hydrogel comprising two components. Schiff bases were formed between aldehyde-modified polyethylene glycol (PEG) and quaternised chitosan (QCS) N [20][66]. Similarly, tunicate cellulose nanocrystals (TCNCs) can be isolated from the mantle of marine animals, and polydopamine (PDA)-coated TCNCs have been used as the reinforcing agent of QCS. Crucially, the quinone group of PDA can interact with the amino group of QCS to form a Schiff base [23][30]. To achieve better mechanical properties, Hu et al. designed a double-crosslinked hydrogel. Briefly, oxidised dextran-dopamine (OD-DA) was prepared by forming a Schiff base structure between the amino group in DA hydrochloride and the aldehyde group in oxidised dextran. Subsequently, the amino group in the QCS reacts with the aldehyde group in OD-DA via a Schiff base reaction. The hydrogel achieved antimicrobial and angiogenesis-promoting effects after encapsulating Ag-NPs and deferoxamine (DFO) [24][69]. Similarly, Liu produced hydrogels by modifying CS with 4-formylphenylboronic acid (FPBA) and innovatively combined the pH-responsiveness with an immune response. Specifically, a Schiff base bond was formed between the amino group of CS and the aldehyde group of FPBA. In addition, the presence of N-formyl-met-leu-phe (fMLP) recruited a large number of neutrophils to gather at the site of infection, creating a low-pH microenvironment that triggered hydrogel degradation. The Fas ligand then induces apoptosis in activated neutrophils and promotes inflammation resolution. Further, macrophages remove apoptotic neutrophils, and this process activates key signalling pathways to promote the anti-inflammatory phenotypic transformation of macrophages and tissue regeneration [25][26][70,71].

Catechol groups are widespread in nature and have been particularly studied in marine mussels, where they act as glues. They can be oxidised or coordinated with metal ions [27][72]. Notably, the catechol moiety functionalisation of QCS enhances its adhesion for use as a dressing, and the tensile adhesion strength of acid-treated hydrogel adhesives is significantly reduced such that they can be removed on demand [28][29][30][31,73,74]. Cationic amino acids can also promote the destruction of the hydration layer between the catechol and the tissue, thus enhancing its adhesion. For example, l-arginine side chains contain many amino groups that favour the formation of Schiff base bonds [31][17]. Tannic acid (TA) is rich in catechol units and contains several highly concentrated phenolic groups (Figure 12B). TA can chelate europium ions, and these complexes promote angiogenesis. Specifically, under acidic conditions, the metal–phenol coordination bonds break and release metal ions that facilitate wound healing [32][29]. In addition, there is no clear indications to suggest that Eu ions is particularly toxic compared to other heavy metals [33][34][75,76].

1.3. Boronic Ester Bonds

Polymers containing borate bonds are ideal pH-responsive biomaterials [36][78]. Boronate bonds are formed by the condensation of molecules containing 1,2- or 1,3-diols with boronic acid derivatives [37][79]. Benzene boric acid (BA) is a Lewis acid with a unionised hydrophobic form and an ionised hydrophilic form in aqueous solution. Notably, ionised BA easily bonds with sodium alginate containing 1,2-diol groups via reversible covalent bonds to form a more hydrophilic structure. When the hydrogel is exposed to an acidic wound, the hydrogel structure is destroyed because of the dissociation of the boronic ester, thus facilitating drug release [38][80].

1.4. pKa

Usually, pH-responsive hydrogels contain either weakly acidic or basic groups. These groups can accept or release protons at different pH values. Acrylic acid (AA) is a weak acid and undergoes deprotonation at pH values above the dissociation constant of its carboxylic acid group, resulting in hydrogel swelling. Weak polycations contain derivatives of ammonia, such as chitosan, p(l-lysine). Notably, the protonation of nitrogen via its lone pairs provides a positive charge to the macromolecular chain. The consequent charge repulsion causes the hydrogels to swell in acidic media below the pKa [39][40][20,46]. Accordingly, Cui et al. created a hydrogel that actively regulated wound pH; briefly, the hydrogel could release or remove H+ ions from different microenvironments to tune the pH of the wound surface precisely and accelerate wound healing [41][81].

1.5. Electrostatic Interactions

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) is a natural protein that can be crosslinked with internal electron-deficient polyesters to form hydrogels via amino-yne click chemistry [42][43][44][45][46][82,83,84,85,86]. Crucially, BSA chains are negatively charged in neutral environments, and, under these conditions, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) can bond to the BSA chain segments via electrostatic interactions. In a weakly acidic microenvironment, the charge of BSA is eliminated, resulting in the release of bonded bFGF, which promotes wound healing [5][45].

The pH plays a key role in physiological processes involved in wound healing [41][81]. pH-responsive hydrogels not only release drugs at the wound sites but also act as pH regulators. However, pH differences between individuals can affect drug release behaviour and must be considered when designing the hydrogel.

2. Thermoresponsive Gels

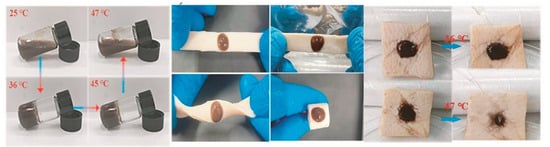

Materials with a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) between room temperature and physiological temperature have been widely used in biomedical engineering (Figure 23). Notably, such hydrogels solidify when their temperature exceeds the LCST, making them ideal candidates for use in irregular wound dressings [47][48][87,88].

N-Isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) is often used for hydrogel preparation [49][50][89,90]. For example, Yan et al. incorporated Ag-nanoparticle-modified reduced graphene oxide nanosheets (Ag@rGO) into a polymer containing NIPAM. On phrase transformation into a hydrogel, strong synergistic coordination interactions between the Ag@rGO nanosheets and collapsed PNIPAM chains maintained the hydrogel state and enhanced its stability at low temperatures [51][36]. However, patients with chronic wounds do not experience significant changes in body temperature; therefore, the temperature stimulus is often used in conjunction with other stimuli when designing hydrogels.

Figure 23. Phase transition of gels at different temperatures and their behaviour on porcine skin [52]. Reproduced with permission.

Phase transition of gels at different temperatures and their behaviour on porcine skin [91]. Reproduced with permission.

3. ROS-Responsive Gels

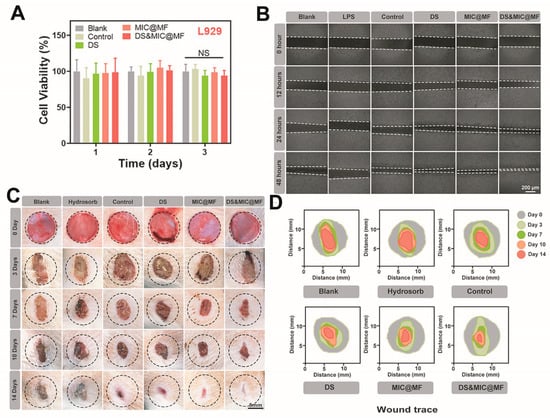

Excess ROS accumulated in wounds not only induce strong inflammatory responses but can also restrict angiogenesis and hinder wound tissue regeneration [53][54][55][56][57][92,93,94,95,96]. The design of ROS-responsive hydrogels is typically based on borate ester bonds and thiol groups. However, an alternative design is the incorporation of ROS-responsive nanoparticles and cross-linking agents. For example, catechol groups can scavenge overproduced ROS and shorten the inflammatory phase [7][53]. Furthermore, in the presence of ROS, the oxidation of TA to its quinone form can increase the degradation of the hydrogel network, thereby promoting rapid drug release [58][97]. For example, Li et al. encapsulated copper ions in an ROS-sensitive TA scaffold, and copper-based metal–phenolic networks (MPNs) released the drug to the wound upon an increase in the ROS levels [59][98]. In addition, Zhao et al. developed an ROS-responsive hydrogel that was cross-linked by the reaction between phenylboronic acid (PBA) and hydroxyl groups. This hydrogel was gradually degraded with an increase in the concentration of H2O2, demonstrating that such hydrogels have the ability to respond to ROS [54][93]. Similarly, TA-conjugated nanoparticles (PPBA-TA NPs) with ROS-scavenging and antimicrobial properties were prepared based on the antioxidant effects of TA and ROS-responsive phenylboronic acid ester (PBAE). The PPBA-TA NPs were then reacted with a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution to form injectable hydrogels. This hydrogel acts as an effective ROS-scavenging agent to alleviate inflammation, promote cell migration, and accelerate wound closure [60][99]. Wu developed a dual-carrying hydrogel that possessed good biodegradability and could achieve the spatio-temporal delivery of diclofenac sodium and Mangifera [55][94], as shown in Figure 34. It promotes blood vessel proliferation and accelerates wound healing. Guo et al. also developed a hydrogel containing micelles (MIC). The thiol groups present in amphiphilic polymers make the MIC responsive to ROS exposure, which could disrupt the MIC and cause the release of encapsulated paeoniflorin [61][100].

ROS-responsive hydrogel dressings reduce ROS levels in the wound environment while enabling intelligent drug release. However, as mentioned above, ROS can be a double-edged sword. For example, maintaining ROS at normal levels allows antimicrobial activity to occur without causing a dramatic inflammatory response [62][101]. This can reduce the use of exogenous antimicrobials, further reducing the risk of side effects.

4. Glucose-Responsive Gels

Hyperglycaemia is typical in diabetes, and glucose-responsive hydrogels are commonly used to treat diabetic ulcers. Glucose contains an ortho-diol group, and PBA forms a more hydrophilic structure when combined with glucose after ionisation, thereby facilitating drug release. In addition, hydrogels doped with glucose oxidase (GOX) and cutanea lectin A can be used for glucose-responsive hydrogel design. Based on this, a glucose-responsive hydrogel microneedle was prepared by the in situ copolymerisation of gelatine methacrylate, the glucose-responsive monomer 4-(2-acrylamide-ethylaminoformyl)-3-fluorobenzene-boric acid (AFPBA), and gluconic insulin (G-insulin). Thus, this hydrogel could control glucose levels by releasing insulin in diabetic patients [63][102]. Similarly, by grafting PBA onto poly(ethylene glycol) succinate–benzaldehyde (PEGS-BA), the PBA moiety formed a dynamic phenylboronic acid ester with a catechol structure. Thus, the hydrogel released metformin in highly glycaemic environments [31][17]. Yang used a hydrogel loaded with GOX to break down excess glucose into hydrogen peroxide and glucuronic acid, thereby altering the microenvironment of hyperglycaemic wounds [64][103]. The hydrogel particles contain complexes of the lectin concanavalin A (ConA) and 2-glucosyloxyethyl methacrylate (GEMA). The GEMA-ConA gel particles selectively recognised glucose, and the swelling ratio of the GEMA-ConA gel particles gradually increased with the increase in glucose concentration. These results indicate that smart gel particles can be used as tools in drug delivery systems to treat diabetes [65][104].

Diabetic ulcers are typical chronic wounds, and the high glucose concentration in diabetic wounds causes vasoconstriction and inhibits blood vessels, which blocks the supply of O2 and impedes the healing process. Further, a high glucose environment can exacerbate bacterial infection [31][66][67][17,105,106]. Therefore, controlling blood glucose levels at the wound site is key in the design of hydrogels for the treatment of diabetic ulcers.

5. Enzyme-Responsive Gels

Wound-specific enzyme expression can be used to design smart-response hydrogels, for example, the degradation of hyaluronan-based hydrogels that are cross-linked by an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)−Fe3+ complex by bacterial hyaluronidase (HAase). On hydrogel degradation, Fe3+ is rapidly absorbed by the surrounding bacteria and subsequently reduced to Fe2+, which reacts with H2O2 to form hydroxyl radicals that damage the proteins and nucleic acids, thus yielding an antibacterial effect [68][107].

MMPs can also degrade the extracellular matrix, which is involved in tissue remodelling, and the overexpression of MMPs can contribute to the development of chronic wounds. Therefore, exosomes have been loaded into MMP-degradable PEG smart hydrogel, and this has been shown to be beneficial for diabetic wound healing [69][108].

Enzyme-responsive hydrogels degrade only in the presence of certain enzymes but remain stable in other environments. Therefore, these smart responsive hydrogels are very specific [70][109]. Crucially, depending on the severity of the wound, the level of enzyme expression varies, and, accordingly, the ability of a hydrogel to release a drug varies, achieving controlled release. If designed as a multi- or cascade response system, they may be favourable for achieving successful wound control.

6. Photo-Responsive Gels

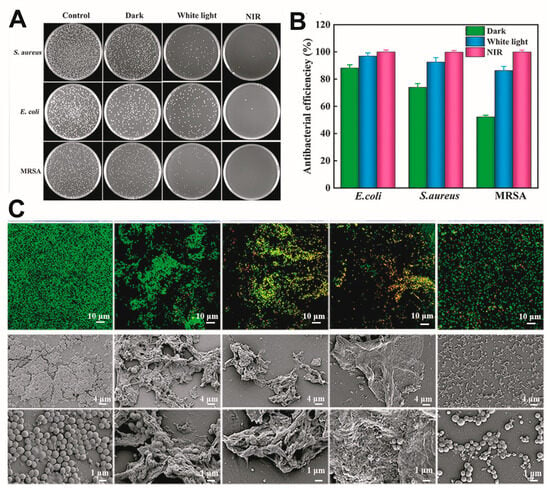

The use of light as a stimulus provides a wealth of inspiration for hydrogel design. Altered polymer conformations or degradation on exposure to light can trigger drug release, and photocurable hydrogels can be used for 3D printing and the development of customised wound dressings [40][71][46,110]. In existing studies, photothermal therapy (PTT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT) have been widely used for chronic wound treatment. The combination of these novel therapies with photo-responsive hydrogels not only maintains the time- and position-controlled release of the cargo but has also been adopted for antibacterial treatment. For example, the heat generated by near-infrared (NIR) radiation can be used to achieve physical sterilisation, promote micro-blood circulation, and release drugs or metal ions [72][73][74][75][76][111,112,113,114,115]. In addition, the heat generated can be used to induce a phase change in the hydrogel to match the shape of a wound [77][116]. During PDT, photosensitisers (PSs) can produce cytotoxic ROS at specific wavelengths and induce bacterial death through oxidative stress. However, some PSs can be repelled by negatively charged bacterial cell membranes. To solve this problem, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), porous materials comprising organic linkers and metal nodes, are often used for PDT [78][117]. The combined use of PDT and PTT can often yield enhanced results [52][91]; see Figure 45.

Photo-responsiveness can also be achieved using encapsulated drug carriers. For example, a carrier encapsulating a drug that breaks down under ultraviolet (UV)/NIR irradiation. In one example, Pluronic F127 containing azo groups was prepared, and cyclodextrin (CD) was used to modify QCS because of the inherent photosensitivity of CDs to azo groups. Under 365 nm UV irradiation, micelles loaded with curcumin were released from the hydrogel, yielding antibacterial effects and encouraging wound healing [23][30]. In another example, on NIR-II light irradiation (1064 nm), the shell of liposomes burst to release an encapsulated drug, thus enhancing the PTT effect for synergistic bacterial elimination [77][116].

The role of oxygen in wound therapy has long been recognised. Wang et al. developed a NIR-excitation-based device that increases the portability of oxygen therapy. The device consisted of an upper layer for replaceable oxygen generation, a unidirectional delivery system, and a lower layer of perfluorinated hyperbranched polymer/gelatine hydrogel. This hydrogel could be used as an oxygen reservoir for precise delivery to wounds. In contrast, Zhang et al. proposed an interesting material that was not strictly a photo-responsive hydrogel. They used calcium alginate hydrogels loaded with Weissella and lipid-membrane-encapsulated Chlorella vulgaris to reduce inflammation and the hypoxic microenvironment for chronic wound healing by producing NO and O2 in dark and light environments, respectively [79][118].

Photo-responsive hydrogels offer the advantage of controlling the release behaviour of the hydrogel by adjusting the timing and intensity of light irradiation. Moreover, light irradiation is a non-contact method that requires inexpensive and portable equipment, making it convenient for clinical use. Common light sources for photo-responsive hydrogels are UV and IR light. However, it should be noted that UV light may cause further damage to the fragile wound tissue after long-term exposure, whereas IR light is safer and can penetrate deeper into the tissue [80][119]. In addition, sunlight is also an important factor to consider in practical applications.

7. Electro-Responsive Gels

Electroactive hydrogels can be constructed using conductive polymers as monomers. In addition, the introduction of metal nanoparticles, metal ions, or carbon compounds (e.g., graphene) can provide hydrogels with conductivity [81][120] and confer additional benefits [82][83][84][121,122,123], such as enhanced physical properties and antimicrobial effects. However, the homogeneity of the dispersion of the conductive medium inevitably affects electrical conduction and must be considered when designing such hydrogels.

Tang et al. designed a conductive scaffold by homogeneously dispersing PDA-reduced-graphene oxide (pGO) in a polymer system. The distribution of pGO in the hydrogel provided a channel for the transmission of electrical signals, which affected cell affinity [85][124]. In addition, Walker et al. recently prepared a biocompatible conductive hydrogel using a choline-based bio-ionic fluid [86][32]. Moreover, Lei created electroactive hydrogels by crosslinking with dynamic borate ester bonds and hydrogen bonds, which improved the current transmission and facilitated intercellular signalling in the tissue [87][33]. Furthermore, Jiang et al. developed a dual-conducting (electrical and ionic) hydrogel with a low impedance across a wide frequency range, resulting in more efficient charge injection during stimulation. This ensured efficient signal exchange and energy delivery between the circuits and soft skin tissue [88][125].

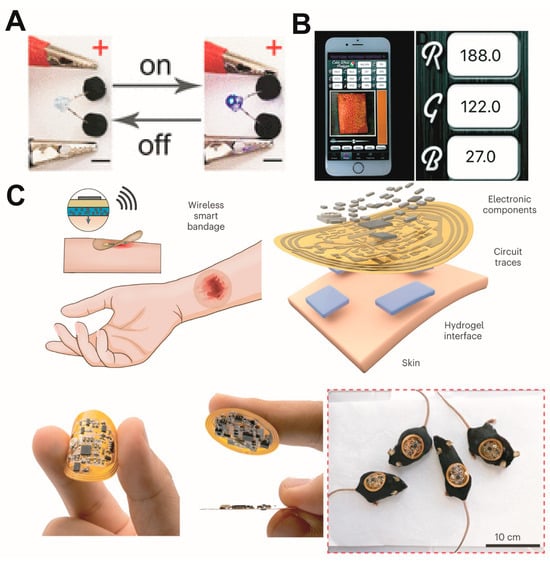

Crucially, this hydrogel can conduct electricity, allowing it to be connected to smart electronic devices that can be loaded with modules for various functions. Hydrogel dressings are now evolving into intelligent integrated treatment-monitoring platforms (Figure 56).