Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Laura-Marinela AILIOAIE and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

The gut microbiota has been shown to contribute to the regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in the renin-angiotensin complex through systemic and local pathways. ACE2 is already known to be the cornerstone of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the COVID-19 disease due to the specific coupling of the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. As SARS-CoV-2 penetrates the cell membrane, it also affects the mitochondria of infected cells, thereby triggering altered metabolism, mitophagy, and atypical levels of mitochondrial proteins in extracellular vesicles.

- immunomodulation

- long COVID

- microbiome

12. Molecular and Cellular Pathophysiological Mechanisms at Gut Level in Long COVID

The pathophysiology of LC is a hot, unresolved, current topic that raises the opinions of many experts who have proposed various scenarios, but which generally have roughly the same guidelines. Although the intestine and the lung apparently function separately, these two organs share the same embryonic origin and similar morphological components. In the fetal period, starting at about the 4th week, the lung bud develops as a protrusion of endodermal tissue from the foregut and then forms the laryngotracheal bud. After the 16th week and throughout infancy, the lung continues to develop and mature [1][47].

Comparing the structures of the lung with those of the intestine, it can be noticed that both are covered with mucous membranes that produce a nitrogenous glycoprotein called mucin, which has a local protective role and a common immunological ability to defend through the mucosa. There is evidence to show that when changes occur in the gut microbiota, signals are also transmitted to the lungs. Thus, gut microbiota and microbial metabolites actively participate in monitoring and regulating lung microbiota composition in cases of inflammation or infection and may even reject lung transplantation [2][3][48,49].

The entry of the SARS-CoV-2 virus into the human body will change the microbiota and the balance of microbial metabolites, which will lead to important systemic disorders with organ damage and the appearance of a variety of clinical symptoms. The gut microbiota has been shown to contribute to the regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in the renin-angiotensin complex through systemic and local pathways. ACE2 is already known to be the cornerstone of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the COVID-19 disease due to the specific coupling of the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. While in the intestine, particularly at the “brush” border of proximal and distal enterocytes in the small intestine, ACE2 expression is more than fourfold higher than in other tissues and is reduced in the lung [4][50], which makes it plausible to consider the intestine as the entry point of the virus into the human body.

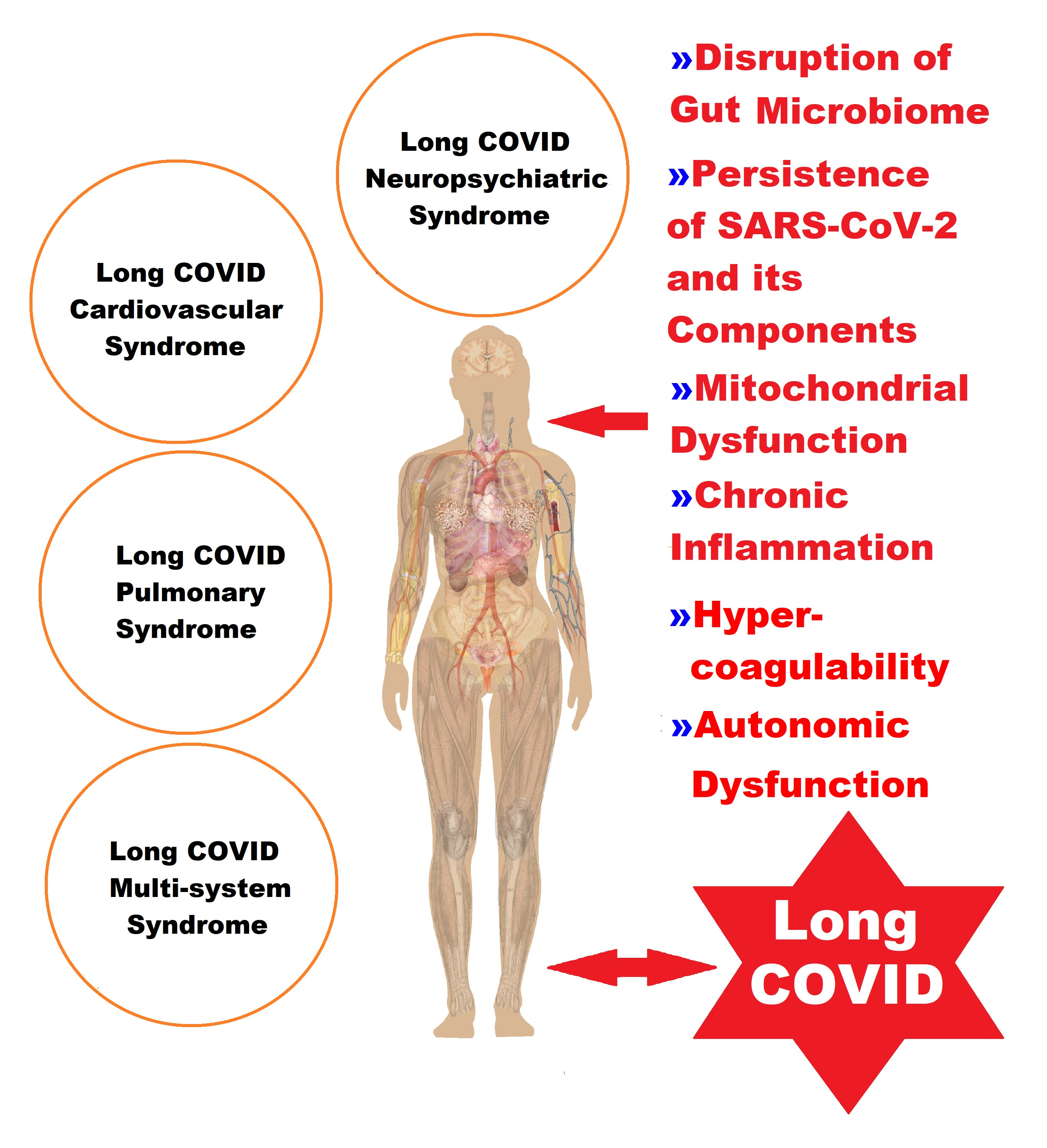

The variety of presentations of LC is illustrated in Figure 1. This has delayed scientific progress in unraveling all its pathophysiological mechanisms, and therefore the approach must be multidisciplinary.

Figure 1. A representation of the complex picture of the clinical manifestations of LC, classified into four syndromes, in correlation with the pathophysiological elements.

Because of research gaps and especially the fluctuation of current hypotheses in the literature, numerous studies are needed to better understand the relationships between the gastrointestinal tract and its involvement in LC, to better manage the disease, and to discover innovative treatments or means of preventive intervention at the digestive tract level [5][51].

The pathophysiological processes leading to the appearance of the more than 200 symptoms of LC are believed to have a multifactorial etiology that includes host conditions (age, sex, ethnicity, genetic factors, metabolic or endocrine diseases, chronic inflammation, immunological imbalances, and autoimmune diseases), viral agents (occult persistence of SARS-CoV-2 or its viral components and reactivation of latent viruses), and downstream effects (grade of lesions from primary acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, vascular endothelial abnormalities, microclots, thrombosis, neurological signaling dysfunction, reduction in tissue oxygen, and disruption of the gut microbiome) [6][7][8][9][10][37,52,53,54,55] (Table 1).

Table 1.

The multifactorial etiology of the pathophysiology of LC.

| Host Conditions | Viral Agents | Downstream Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Age Sex Ethnicity Genetic factors Metabolic/endocrine diseases Chronic inflammation Immunological imbalances/autoimmune diseases |

Occult persistence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 viral components Reactivation of latent viruses [(Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes simplex virus 1, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), and human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7)] |

Grade of lesions from primary acute SARS-CoV-2 infection Vascular endothelial abnormalities Microclots Thromboses Dysfunctional neurological signaling Reduction in tissue oxygen/hypoxia Disruption of the intestinal microbiome |

23. Gut Microbiota Dynamics in Long COVID

A growing number of studies have shown that the gut bacterial microbiome of patients with COVID-19 was greatly altered compared to healthy people, in that there was a significant reduction in commensal bacteria, which were replaced by opportunistic pathogens. In healthy individuals, the taxa Eubacterium, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia, and Lachnospiraceae form an integral and predominant part of the natural gut microbiome, whereas in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, their feces were enriched with opportunists, which include Clostridium hathewayi, Actinomyces viscosus, and Bacteroides nordii. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome that occurred during the manifestations of COVID-19 has been observed to persist even in patients who have recovered from the disease, and changes in the microbiota could underlie chronic symptoms, demonstrating that the gut microbiome is directly correlated with the condition of host health in the LC phase [11][12][13][89,90,91].

34. Mitochondria and Long COVID—The Hidden Molecular Connections and the Quantum Leap

Over the past two decades, the role of mitochondrial function in health and disease has become increasingly recognized, and rapid advances in our scientific knowledge show tremendous promise to one day elucidate the mysteries of this ancient organelle to therapeutically modulate it when it is necessary. However, the researchers still have much to clarify and understand about how viruses take control of infected cells to multiply, relying entirely on hijacking the host cell’s own molecular machinery, strategically influencing cellular metabolism, and altering not only the structure but also the functions of the organelles inside the cell, implicitly the mitochondria, which could be a key factor in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Mitochondria are versatile and critical metabolic structures not only for energy production but also for modulating cellular immunity through several mechanisms, which generate cell apoptosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling, mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS) activation, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)-dependent mitochondrial immune activation. These events are regulated by mitochondrial dynamics and its damage-associated molecular patterns (mtDAMPs), complex phenomena by which mitochondria change, including their length and connectivity (structure), in response to the stress generated by the virus that hijacks all processes to avoid the immune response mediated by mitochondria to survive and proliferate, thus generating even more cellular stress and inducing disease progression [14][15][16][103,104,105]. Although post-viral fatigue syndrome has been known for decades, the mechanism by which viruses cause this syndrome is still unknown, and it is assumed that the breakdown of mitochondrial metabolic pathways could be the main cause. Similarly, COVID-19 infection could produce a redox imbalance that causes long-term, the so-called LC. There is a bidirectional connection between redox dysregulation, systemic inflammation, the damaged ability to generate adenosine triphosphate, and the general hypometabolic condition. Comprehending all these phenomena and the molecular basis of LC may lead to innovative management modalities [17][18][19][106,107,108]. LC is still an unresolved puzzle present in both children and adults [20][121], and the molecular mechanisms involved in the modulation of intestinal permeability with impact on autoimmunity [21][122], as well as the onset and persistence of LC symptoms as a consequence of the complex interaction between infection, dysbiosis and inflammation at the molecular and cellular levels, could advance new lines of medical action to avoid LC. Complement activation in a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and chronic or persistent inflammatory response associated with complement system dysregulation, microthrombosis phenomena, and endothelial dysfunction [22][128] could trigger the various manifestations in LC.To prevent a decline in the quality of life among LC patients, follow-up and assistance through individualized health programs are essential.