Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Peter Kokol and Version 2 by Fanny Huang.

Obesity is a complex disease that, like COVID-19, has reached pandemic proportions. Consequently, it has become a rapidly growing scientific field, represented by an extensive body of research publications.

- obesity

- weight loss

- motivation

- synthetic knowledge synthesis

1. Introduction

Obesity is a complex disease that, along with COVID-19, has reached pandemic proportions [1][6]. At the same time, it poses a significant long-term health problem, with enhanced involvement of younger populations. Globally, there are more people who are obese than underweight and also more deaths are connected to obesity than underweight, with the exception of some parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Overweight and obesity and related chronic diseases (high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, etc.) are largely preventable by the consumption of healthier foods and regular physical activity, with these being the easiest choices and also the most accessible, available, and economically affordable [2][7].

Nevertheless, the promotion of and access to healthy lifestyles are needed to consider the full effect of individual responsibility. Therefore, at the societal level it is important to support individuals through the sustained implementation of evidence-based and population-based policies in concordance with recommendations to prevent obesity. An example of such a policy is a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. Moreover, low-income individuals must gain access to more physical activity options and healthier dietary choices that are economically affordable for everyone [2][7].

2. Weight Management on the Level of Primary Healthcare

2.1. Weight Management in Overweight Patients as Part of Primary Care Supported by Qualitative Research

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians screen all adults for obesity and refer them to an intervention called lifestyle modification, which includes diet, physical activity, and behavioral therapy. Participants lost up to 8% of their weight in 6 months and were provided with, at least, monthly counseling to prevent weight regain. They are currently introducing ICT to monitor food intake, activity, and weight to make interventions even more successful [3][42]. Nutritional counseling in a primary care environment is recognized as a starting point in the management of obesity [4][43], especially if supported by digital technology [5][6][44,45]. If integrated into family-centered pediatric weight management, it has been shown to be very successful in pediatric populations [7][8][46,47], but the sustainability of healthy lifestyle changes requires continuous support [9][48]. The importance of long-term counseling support has been confirmed by Kumanyika et al. [10][49], who showed that each additional coaching visit is associated with a 0.37 kg greater estimated 24-month weight loss.

2.2. Barriers to Weight Loss

Weight maintenance remains a challenge, and understanding the barriers that patients experience during weight loss is crucial to improving the weight-loss and maintenance processes [11][50]. Factors such as a lack of resource support, logistics, knowledge regarding weight-loss interventions, understanding of the root causes of obesity, patient readiness for change, and family physicians’ perceptions about surgical weight loss have been identified as barriers to successful weight management [12][51]. Delahanty et al. [13][52] identified different types of barriers, such as a lack of self-monitoring, insufficient physical activity, internal thought/mood cues, vacation/holidays, social cues, access/weather, time management, and aches/pains during exercise. Another study highlighted habitual overconsumption; proximity and convenience of food available; momentary lack of motivation and sense of control; overeating triggers such as social media; eating with family, friends, and colleagues; provision of food by someone; emotions (e.g., sad and stressed); and physiological conditions [14][53].

2.3. Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery and Body Self-Image

Behavior and body image can affect the relationship between obesity and weight maintenance. Body image concerns may be one reason for choosing surgery [15][54]. In a study conducted by Faccio et al. [16][55], participants reported that even one year after surgery, they behaved as if they were still obese, and greater awareness was needed to help them realize that they were no longer obese. In another study, participants experienced little or no control in relation to food and eating before the bariatric procedure, but they believed that surgery would be the first step toward gaining control in this area. One year post-operatively, they acquired established routines and had higher self-esteem. However, after two years, fear of weight gain resurfaced, and their self-image became more realistic [17][56]. A systematic review of post-bariatric surgery body images revealed that adapting to a new body can be challenging because of a persistently obese view of the self. Furthermore, patients are dissatisfied with excessive skin after bariatric surgery and a negative self-image is replaced by dissatisfaction [18][57].

Weight Regains after Bariatric Surgery

Post-bariatric weight gain may be associated with problematic or eating-disordered behaviors, such as loss of control of eating and depression; therefore, psychiatric treatment for such patients is advised [19][58]. Another important factor is patient self-efficacy expectations, which are positively associated with weight loss [20][59]. Positive psychological well-being, a novel approach to improving adherence by increasing positive associations with health behaviors, including physical activity after bariatric surgery, or other similar behavioral interventions, such as reward-based eating or self-compassion, could help patients maintain lifestyle changes [21][22][60,61]

2.4. Evolution of Research

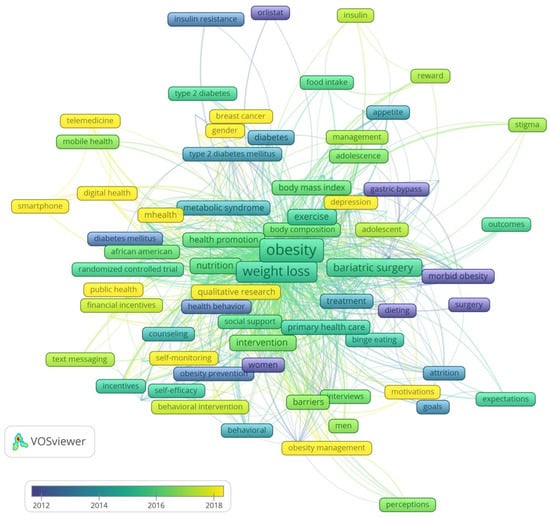

The historical trends are presented in Figure 1. Until 2012, research in the field of weight loss and motivation focused on morbid obesity, body self-image, diet, surgical techniques for weight loss, and the internet as an opportunity to motivate and search for useful information. In the 2012–2014 period, the research focus shifted to the psychological factors of obesity and weight loss in terms of eating habits and health concerns. Research on the association between obesity and diabetes was also initiated. The phenomenon of motivation in connection with behavioral change and obesity/weight loss began to be intensively researched in the 2015–2016 period. During this period, research on bariatric surgery became popular. In the 2017–2018 period, intriguing research was conducted in the fields of behavioral change interventions, motivating changes, and obstacles to weight loss. One of the more interesting concepts that appeared in this period is “self-determination theory”. Research conducted after 2018 has been devoted to the use of digital health, smart technologies, telemedicine, and social media in motivational interventions and weight maintenance. The number of qualitative studies has also increased. Self-control and sleeve gastrectomy are also interesting research trends. A virtual model of weight achievement and intensive treatment employed during COVID-19 is also effective for weight reduction and maintenance [23][62].

Figure 1.

Trends in motivation in weight loss research.

2.5. Research Cooperation

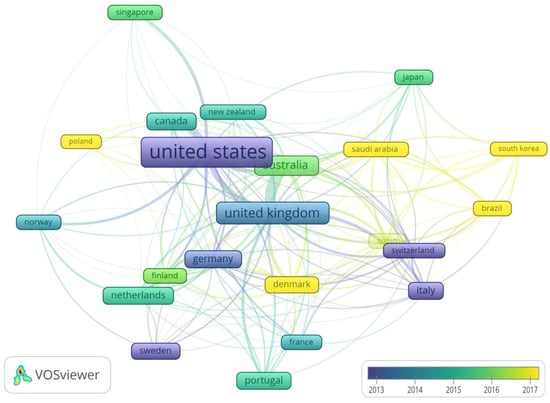

The country cooperation based on co-authorship is shown in Figure 2. Evidently, 22 countries have published 20 or more papers. The United Kingdom and Australia (n = 43), the United States and Canada (n = 28), the United States and the United Kingdom (n = 21), and the United States and Australia (n = 15) were the countries with the highest number of international publications. The most cited publications were from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. The oldest publications were from the United States, Italy, Switzerland, and Sweden, and the youngest from Poland, Denmark, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea (Figure 2). Research cooperation on the motivation for weight loss between developed and less-developed countries is almost nonexistent.

Figure 2. Country cooperation map based on co-authorships. The colors represent the average age of the publications, and the rectangle size is proportional to the number of citations.