Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Fanny Huang and Version 2 by Fanny Huang.

Plants have been vital to human survival for aeons, especially for their unique medicinal properties. Trees of the Eucalyptus genus are well known for their medicinal properties. The Corymbia genus comprises bloodwood, spotted and ghost gum trees, which were previously classified as subspecies of the Eucalyptus genus. In 1995, however, DNA and morphological research concluded that bloodwood, spotted and ghost gum trees were genetically distinct from other Eucalyptus species, and they were, therefore, reclassified as members of the Corymbia genus of the Myrtaceae family

- Corymbia

- Ethnopharmacology

- Biological Activities

- Myrtaceae

- Essential Oils

- Ethnomedicine

1. Introduction

Over the past century, pharmaceutical interventions have become increasingly important in the treatment of ailments around the world, particularly in more developed nations. This is reflected in the ever-increasing investment of the pharmaceutical industry into drug research and development, which is reported to have increased from $2.3 billion USD in 1981 to $83 billion USD in 2019 [1]. This trajectory is unlikely to change anytime soon given the increasing prevalence of resistance to anti-microbials [2], and the need for more treatments to deal with the continual rise of conditions such as metabolic disorders and autoimmune diseases [3][4]. In less developed nations, however, access to pharmaceutical treatments is still limited, and as such, they continue to rely heavily upon medicinal plants for the treatment of many ailments [5].

For millennia, plants have been utilised by native cultures across the world for food, shelter, livelihood and medicine [6]. Even today, it is estimated that 65–80% of the world′s population continues to rely upon natural remedies due to a lack of access to modern medicine [7]. Ironically, it is to the native populations of the world who lack access to modern medicine that many researchers have been turning for inspiration and direction. Ethnopharmacology is becoming increasingly prevalent as a means of discovering new drug leads, as indigenous populations′ knowledge of plant medicinal properties can be utilised to direct the search for bioactive compounds [8]. The popularity of ethnopharmacological drug discovery is unsurprising given that approximately 40% of all small molecule therapeutics are natural products or derived from natural product pharmacophores [9] and that many of the over 50,000 medicinal plants known worldwide have not been screened for bioactive compounds to this day [7][10]. This is especially true of the many medicinal plants endemic to Australia.

Indigenous (aboriginal) Australians have lived from the land for thousands of years and have an intimate connection to and knowledge of endemic flora and their medicinal properties. Trees of the Eucalyptus genus (Myrtaceae) represent perhaps one of the most renowned Australian aboriginal bush medicines. These species are well-known for their volatile essential oils (EOs) which are extracted from the leaves and used to treat respiratory infections and inflammatory conditions around the world [11]. Further, Eucalyptus trees, while endemic to Australia, have been cultivated around the world and have become essential medicinal plants for other native populations around the world [12][13].

Despite the extensive knowledge and fame of the Eucalyptus genus for its medicinal properties, comparatively little is known about species of the Corymbia genus, which have similar phytochemical and medicinal properties [14]. The Corymbia genus comprises bloodwood, spotted and ghost gum trees, which were previously classified as subspecies of the Eucalyptus genus. In 1995, however, DNA and morphological research concluded that bloodwood, spotted and ghost gum trees were genetically distinct from other Eucalyptus species, and they were, therefore, reclassified as members of the Corymbia genus of the Myrtaceae family [15][16]. One key morphological characteristic of many Corymbia spp. is their production of kino, a resinous exudate which is used to treat many ailments by the aboriginal peoples of Australia [17]. Along with the known ethnomedical uses of various Corymbia species, a broad range of biological activities are observed in the EOs, crude extracts and compounds isolated from this genus [18][19][20][21], highlighting the potential of the Corymbia genus to provide new drug leads and treatments for many common diseases.

2. Ethnomedical Uses of Corymbia Species

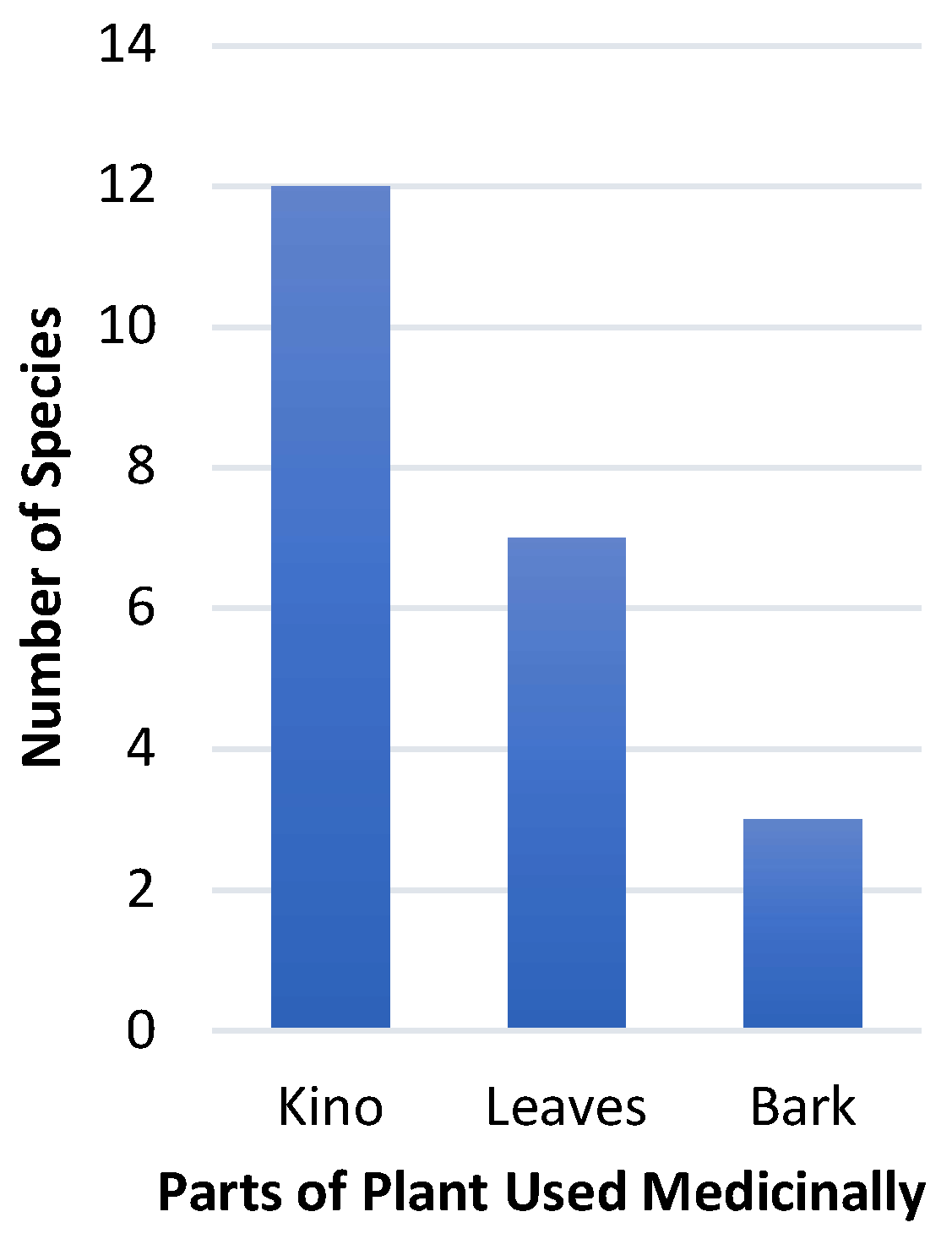

The ethnopharmacological data for the Corymbia genus presented in Table 1 show that of the 115 species known, ethnomedical uses have only been reported for 14 of these species. Of those 14 species, the kino was used medicinally in 12 spp., followed by the leaves (7 spp.) and bark (3 spp., Figure 1).

Figure 1. The use of plant parts in ethnomedically utilised Corymbia species (N = 14).

Table 1. Ethnopharmacological data for Corymbia spp. plants and biological testing performed.

| Species | Origin of Plant Studied | Part(s) of Plant Studied § | Ethnomedical Uses | Compounds Isolated | Biological Testing Performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. bleeseri (Blakely) | Australia | K | Kino is applied to cuts and wounds to promote healing [22] and is used to treat skin lesions, scabies, cramps, sore throats and coughs [17]. | – † [23] | – |

| C. calophylla (Lindl.) |

Australia | K, B | Kino is used to treat chronic bowel conditions and dysentery [17]. | Aromadendrin; kaempferol; ellagic acid [24]; oleanolic acid acetate [25]; (+)-afzelechin *; pyrogallol; (+)-catechin [26]; leucopelargonidin *; aromadendrin; sakuranetin [27]. | – |

| C. citriodora (Hook.) | Algeria; Australia; Bangladesh; Benin; Brazil; China; Colombia; Cote d′Ivoire; Democratic Republic of the Congo; Egypt; India; Türkiye; Kenya; Madagascar; Morocco; Nigeria; Pakistan; Portugal; Taiwan; Thailand; USA | L, K, T, Fr, H | Leaves and bark are used as antiseptics, expectorants, and treatments for influenza and colds, toothaches [28][29] and diarrhoea [29]; hot water extracts of the dried leaves are used to treat colds, influenzas, respiratory infections and sinus congestion [30][31][32][33][34][35]; water extracts are also used to treat, vomiting, nausea, indigestion, bloating, irritable bowel and abdominal pain [30]; leaves are used in India and Africa to treat obesity, ageing, cardiovascular illnesses, diabetes and respiratory problems [36][37]; in Nigeria, leaves are boiled and consumed for the treatment of typhoid fever, stomach aches and malaria [38]; Dharawal people use leaves to treat inflammation, wounds and fungal infections [39]. Kino is traditionally used to treat diarrhoea and bladder inflammation and is applied to cuts and abrasions [40][41]. |

Shikimic acid; quinic acid; glutaric acid; succinic acid; malic acid; citric acid [42]; (±)-(trans)-p-menthane-3,8-diol; (±)-(cis)-p-menthane-3,8-diol [43]; 6-[1-(p-hydroxyphenyl) ethyl]-7-O-methyl aromadendrin [40]; citronellol acetate [44]; 3,5,4′,5″-tetrahydroxy-7-methoxy-6-[1-(p-hydroxy-phenyl)ethyl]flavanone; 3,5,7,4′,5″-pentahydroxy-6-[1-(p-hydroxy-phenyl)ethyl] flavanone [45]; 1-O,2-O-digaloil-6-O-trans-p-coumaroyl-β-D-glucoside; 1-O-trans-p-coumaroyl-6-O-cinamoil-β-D-glucoside; α- and β-6-O-trans-p-coumaroyl-D-glucoside; 7-methylaromadendrin-4′-O-6″-trans-p-coumaroyl-β-D-glucoside; aromadendrin; aromadendrin-7-methyl ether; naringenin; sakuranetin; kaempferol-7-methyl ether; gallic acid [46]; citriodora A *; 3β,7β,25-trihydroxycucurbita-5,23-(E)-dien-19-al; kuguacin A; kuguacin H; 3β,7β-dihydroxy-25-methoxycucurbita-5,23-(E)-dien-19-al; kuguacin S [47]; trans-calamenene; T-muurolol; α-cadinol; 2β-hydroxy-α-cadinol; 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde; 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid; linoleic acid; squalene; α-tocopherol; erythrodiol; morolic acid; betulonic acid; cycloeucalenol; cycloeucalenol vernolitate *; β-sitosterol; β-sitosteryl-β-D-glucoside; sitostenone; yangambin; sesamin [48]; rhamnocitrin; 6-[1-(p-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]-7-O-methyl aromadendrin *; 6-[1-(p-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]-rhamnocitrin; kaempferol; 7-O-methyl aromadendrin [49]; citriodolic acids A–C *; rosmarinic acid; ferulic acid; gallic acid [50]; ellagic acid; gallic acid; quercetin; myricetin; 3-O-methylellagic acid-4′-O-α-L-rhamnoside; quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactoside; kaempferol-3-O-β-D-glucoside; quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucuronide; quercetin-3-O-rutinoside; 3,3′,4-tri-O-methylellagic acid-4′-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl [39]; rhodomyrtosone E *; betulinic acid; oleanolic acid; ursolic acid; corosolic acid; asiatic acid; madasiatic acid; euscaphic acid; 5,7,4′-trihydroxy dihydroflavanol; isoquercitrin; isomyricitrin; myricitrin; gallic acid [51]; citrioside A *; hesperidin; baicalin; puerarin; trifolirhizin 6′-monoacetate; trifolirhizin [52]; citrioside C *; kaempferol-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl (12)-α-L-rhamnoside; kaempferol-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside; quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside [53]; 7-O-methylaromadendrin; aromadendrin-dimethyl ether; 7-O-methylkempferol; ellagic acid [54]. | Anti-Fungal Activity: potent fungicidal activity of leaf EO against C. albicans, C. krusei and C. tropicalis [55]; anti-fungal activity of leaf EO against M. canis, M. gypseum, T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum [56]; anti-fungal activity of leaf EO against A. alternata, C. lunata and B. specifera [57]; leaf EO enhanced wound healing rate of C. albicans-infected wounds in rats [44]; anti-fungal activity of petroleum ether leaf extract [58]; anti-fungal activity observed in leaf/twig EO [33]; fungicidal activity of leaf EO against C. albicans [36]; anti-fungal activity against P. notatum, A. niger and F. oxysporium observed for 7-O-methylaromadendrin, 7-O-methylkaempferol and ellagic acid [54]. Anti-Bacterial Activity: anti-bacterial activity of leaf extracts against M. aureus, E. coli and My. Pheli [54]; anti-bacterial activity of petroleum ether leaf extract [58]; anti-bacterial activity observed from leaf/twig EO [33]; anti-bacterial activity of leaf EO against S. sanguinis and S. salivarius with anti-biofilm activity [18]; bactericidal activity of leaf EO against E. coli and S. aureus [36]; bactericidal activity of leaf EO [37]; anti-bacterial activity of aqueous EtOH leaf extract [59]; anti-bacterial activity of fruit and twig EOs against several species [60]; anti-bacterial activity of leaf extract against S. aureus [61]; airborne TB inhibition by volatile leaf EO components [62]; leaf EO inhibits the growth of V. campbellii BB120 bacteria [63] and treatment of brine shrimp infected with V. campbellii with EO enabled their survival [64]. Acaricidal Activity: acaricidal activity of leaf EO against A. nitens larvae [65]; leaf EO and citronellal reduced R. microplus reproductive parameters and increased larval mortality [66]. Anti-Protozoal Activity: anti-trypanosomal activity of leaf EO against T. brucei [67], T. evansi [67] and T. cruzi [68]; anti-trypanosomal activity of EtOH extract against T. brucei [69]; anti-plasmodial activity observed against P. falciparum 3D7 and INDO strains [70]. Anti-Viral Activity: potent anti-viral activity against RSV observed in citriodolic acids A–C [50], citrioside A [52] and quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside [53]. Insecticidal Activity: fumigant activity against the R. speratus [71]; larvicidal activity against A. aegypti [72]; larvicidal activity of leaf hexane extract against An. Stephensi, Cx. Quinquefasciatus and Ae. Aegypti [73]; larvicidal activity of aqueous EtOH leaf extract [59]; larvicidal activity of leaf EOs against S. frugiperda larvae [74]; insecticidal activity of MeOH extract against T. castaneum [75]. Anti-Oxidant/Anti-Inflammatory Activity: leaf EO showed significant inhibition and IC50 values of 4.8–344 µg/mL in DPPH assays [31][33][76][77][78][79][80]; floral EO showed moderate DPPH inhibition [31]; leaf EO showed potent peroxidation inhibition in a linoleic acid/β-carotene assay [33]; leaf and floral EOs showed micromolar protease inhibition [31]; anti-inflammatory properties via inhibition of LOX-1 [28]; kino EtOH extract [32] and flavanols isolated from kino exhibited 15-LOX inhibition [49]; potential anti-inflammatory and anti-viral activity of leaf EO via LOX and ACE2 inhibition [81]; potent anti-inflammatory and gastroprotective properties of ellagitannin fraction in rats [20]; potent inhibition of LPS-induced inflammation in RAW264.7 macrophages [82]; ellagic acid isolated from C. citriodora leaves showed anti-inflammatory and gastroprotective activity in an EtOH-induced acute gastric ulcer mouse model [39]; leaf EO showed significant anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity in rats and mice [35]. Anti-Diabetic Activity: betulinic acid and corosolic acid isolated from C. citriodora leaves enhanced GLUT-4 translocation activity [51]; aqueous leaf extract enhanced insulin secretion and glucose uptake in vitro and had anti-diabetic effects in high-fat-fed rats [80][83]; EtOH leaf extract had anti-diabetic and insulinotropic activity in high-fat-fed rats [21]. Anti-Cancer Activity: Anti-proliferative activity of aqueous extract against MIA, PaCa-2, BxPC-3, CFPAC-1 and HPDE cells [30]; leaf EO exhibited anti-proliferative activity against THP-1 cells [84]; EtOAc fraction of EtOH kino extract and isolated 6-[1-(p-hydroxyphenyl) ethyl]-7-O-methylaromadendrin exhibited potent anti-proliferative activity and apoptosis induction in B16F10 melanoma cells [40]; aqueous fraction of EtOH kino extract inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells [41]; leaf EO showed potent anti-cancer activity against HCT-116, MCF-7 and hepG-2 cells [76]; moderate cytotoxicity of leaf EO against A-549, PC-3, T98G and T47D cells [57]; fruit EO was cytotoxic toward A549, HeLa and CHOK1 cells [85]. Other Bioactivity: aqueous extract of leaves and branches detoxified mycotoxins aflatoxins B1 and B2 [86]; leaf EO exhibited anti-spasmodic effects via inhibition of acetylcholine-induced contraction of a rat ileum [29]; mosquito repellence [43][87]; acetone leaf extract delayed loss of climbing ability and reduced oxidative stress in transgenic Drosophila expressing h-αS in the neurons [88]. |

| C. dichromophlo-ia (F. Muell.) | Australia | – | Kino infusions are used to treat respiratory complaints [17]; mixed with water as a general tonic and analgesic mouth rinse for toothaches [17][89]; mixed with water for sore eyes, lips, wounds, skin lesions, burns, scabies, cramps and sore throats [17]; kino sucked or decoction prepared as tonic for cardiac complaints [17][89]. Leaves are boiled in water and consumed for respiratory conditions [22]. |

– | – |

| C. eximia (Schauer) | Australia | L | Dharawal people use leaves to treat colds, fever, chest and muscle pain, extreme diarrhoea and syphilitic sores and as a wash for joints [90]. | – | Ethanolic leaf extract showed anti-inflammatory properties in RAW 264.7 macrophages [90]. |

| C. gummifera (Gaertn.) | Australia | K, L | Leaves used for respiratory conditions and as a wash for joints [90]. Leaves and kino are used as haemostatics and to treat diarrhoea, ringworm, venereal sores and other STIs [17][91]. |

Aromadendrin; ellagic acid [24]. | Moderate anti-inflammatory activity observed in RAW 264.7 macrophages [90]. |

| C. intermedia (R.T. Baker) | Australia | K, L, FL | The Yaegl aboriginal community uses kino to treat warts and wounds and as a haemostatic [92][93]. | Intermediones A–D *; (4S)-ficifolidione [19]. | Intermediones A, B and D showed moderate anti-plasmodial activity against P. falciparum 3D7 [19]; intermedianone A also displayed anti-proliferative activity against HEK-293 cells [19]. |

| C. maculata (Hook.) | Australia, Egypt, India, Nigeria | L, K, B | Kino is applied directly to burns, and used to treat muscle aches, cramps, wounds, scabies, ringworm, venereal sores, muscle aches and cramps [94]; kino is also ingested to treat coughs, colds, influenza and other infections, dysentery and diarrhoea [94]; kino is also used to treat chronic bowel inflammation [17]. Dharawal people use leaves to treat respiratory infections, fever, chest and muscle pain, and as a wash for joints [90]; juice extracted from the leaves is used to treat paralysis and rheumatism in India [30]. In Australian bush medicine, gum derived from the bark is used to treat bladder infections [30]. |

β-Germacrenol [95]; 8-demethyl eucalyptin; 8-demethyleucalyptin; myrciaphenone A–B; quercetin-3-O-β-D-xyloside; myricetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside; quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactoside; quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside; quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside; syringic acid; gallic acid-3-methyl ether; gallic acid-4-methyl ether; gallic acid [96]; ellagic acid; p-coumaric acid; naringenin; 7-O-methylaromadendrin [97]; leucopeargoniidin-3-O-α-L-rhamno-β-D-glucoside *; 5,7-dihydroxy 4′-methoxy flavanone [98]; cinnamic acid; 7-O-methyl aromadendrin; sakuranetin; 1,6-dicinnamoyl-O-α-D-glucoside* [99]; p-coumaric acid; 1-O-cinnamoyl 6-O-coumaroyl-β-D-glucoside *; 7-methylaromadendrin-4′-O-(6′′-trans-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucoside * [100]; 3β,13β-dihydroxy-urs-11-en-28-oic acid [101]; 6-[1-(p-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]-7-O-methylaromadendrin [40]. | Potent anti-leishmanial activity against L. donovani observed in eucalyptin, Myciaphenone A and five flavonoid glycosides [96]; potent anti-trypanosomal activity against T. brucei [101]; leaf aqueous extract inhibited PaCa-2 cell proliferation [30]; MeOH extract showed anti-inflammatory properties in vitro [102]; EtOH leaf extract exhibited anti-inflammatory properties in RAW 264.7 macrophages [90]; MeOH kino extract showed significant anti-inflammatory properties in rats [102]; 7-O-methylaromadendrin, sakuranetin and 1,6-dicinnamoyl-O-α-D-glucoside isolated from the kino [99] exhibited anti-oxidant and hepatoprotective properties in rats [103]. |

| C. opaca (D.J. Carr & S.G.M. Carr) | Australia | – | Kino is applied directly to scabies, cuts and sores, and the gum is boiled in water and applied to sore eyes [22]. | – | – |

| C. papuana (F. Muell.) | Australia | B | Kino is used as a decoction for sores, cramps, burns, pains and cuts, skin lesions, scabies, sore throat and cough; infusions are used for colds and sore eyes [17]. | Morolic acid [104]. | – |

| C. polycarpa (F. Muell.) | Iran | L | Kino is used to treat sores, burns, cuts, burns, yaws, ulcers, dysentery and toothaches [17][91]. | – † [105][106] | Anti-bacterial activity of leaf EO against S. aureus [107]. |

| C. terminalis (F. Muell.) | Australia | – | Kino is applied to wounds, cuts, sores, toothaches, scabies, skin lesions scabies and cramps [17][22]; it is also taken in water for diarrhoea, headaches, coughs, heart disease and blood conditions [17][22][89]. Bark is used to treat dysentery [91]. |

– ‡ [108] | – |

| C. tessellaris (F. Muell.) | Australia | – | Kino is consumed for dysentery [17]; gum is used for constipation [91]. | –† [109] | – |

| C. torelliana (F. Muell.) | Australia, Papua New Guinea, Nigeria | K, L, B FR, FL | Leaves are used to treat gastrointestinal disorders, sore throats, bacterial respiratory and urinary tract infections [110]; leaf poultice is applied to ulcers and wounds [110]; hot water extracts of leaves are used in Nigerian traditional medicine as an analgesic, anti-inflammatory, cancer treatment and to alleviate intestinal disorders [111]. | Torellianones A–F *; torellianol A *; ficifolidione; (4R)-ficifolidione; kunzeanone A–B [112]; (+)-pinene; (±)-α-pinene; (-)-β-pinene; ocimene; (+)-aromadendrene; benzaldehyde [113]; 5-hydroxy-7,4′-dimethoxy-6-methylflavone [114]; hydroxymyristic acid methyl ester; methyl (E)- and (Z)-6-(8-oxooctadecahydrochrysen-1-yl)non-7-enoate [115]; (2S)-cryptostrobin; (2S)-stroboponin; (2S)- cryptostrobin 7-methyl ether; (2S)- desmethoxymatteucinol; (2S)-pinostrobin; (2S)-pinocembrin [116]; 3,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavanone; 3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavanone; 4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone; 3,4′,5-trihydroxy-7-methoxyflavanone; (+)-(2S)-4′,5,7-trihydroxy-6-methylflavanone; 4′,5,7-trihydroxy-6,8-dimethylflavanone; 4′,5-dihydroxy-7-methoxyflavanone [117]. |

Torellianones C–F, (4R)- and (4S)-ficifolidones and kunzeanone A exhibited anti-plasmodial activity against P. falciparum [112]; potent in vitro anti-H. pylori activity of leaf and stem extracts across various strains [110]; leaf and stem bark extracts and isolated compounds showed anti-TB activity [115]; anti-bacterial activity of stingless bee propolis, fruit resin and isolated flavonoids against S. aureus [116]; moderate anti-bacterial activities and potent cytotoxicity to PC-3, Hep G2, Hs 578T and MDA-MB-231 exhibited by leaf and fruit EOs [111]; anti-tuberculosis activity observed in hydroxymyristic acid methyl ester and methyl (E)- and (Z)-6-(8-oxooctadecahydrochrysen-1-yl)non-7-enoate [115]; MeOH extract of leaves and bark showed anti-secretory and gastroprotective properties in rats with EtOH/HCl-induced ulceration [118]. |

§ Code for part of plant studied: L = leaves; K = kino/resin/exudate; B = bark; FR = fruit; FL = flowers; T = twigs; H = heartwood. * Novel compound(s) that were isolated. † No compounds were isolated; however, a chemical profile of the leaf EO was reported. ‡ Raman spectrum of kino previously obtained.

The kino of Corymbia genus plants is commonly applied directly to cuts (haemostatic), burns and wounds by aboriginal people and is added to water to make antiseptic washes [17][22][92][93][94]. Kino is applied locally to treat infections such as ringworm, venereal sores and other STIs [17][91] and is also ingested to treat pulmonary and heart complaints, gastrointestinal and bladder infections, diarrhoea and dysentery [17][40][41][89]. The kino of C. terminalis is also used as a tonic to treat blood conditions and to relieve headaches [22].

Hot water extracts of Corymbia spp. leaves are frequently used by aboriginal people as antiseptics for wounds and infections, analgesic baths for rheumatism and are ingested to treat respiratory and urinary tract infections and severe diarrhoea [28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][90]. The leaves of C. citriodora, C. maculata and C. torelliana have also been adopted by the native populations of Cote d′Ivoire, Nigeria, India and Brazil for the treatment of toothaches, obesity and diabetes, respiratory and intestinal complaints, skin conditions, cancer, typhoid fever and malaria [28][30][34][35][36][37][38][111].

The less commonly used barks of the Corymbia spp. also possess medicinal properties. Gum derived from the bark of C. maculata is used in Australian bush medicine to treat bladder infections [30], while the bark of C. terminalis is used by aboriginal communities in Queensland to treat dysentery [91]. The bark of C. citriodora is also reported to be used in Nigeria as an antiseptic and expectorant and as a treatment for toothaches, diarrhoea and snake bites [29].

References

- PhRMA. PhRMA Annual Membership Survey. 2020. Available online: https://phrma.org/-/media/Project/PhRMA/PhRMA-Org/PhRMA-Org/PDF/P-R/PhRMA_Membership_Survey_2020.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910.

- Ford, E.S.; Giles, W.H.; Mokdad, A.H. Increasing Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome Among US Adults. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2444–2449.

- Conrad, N.; Misra, S.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G.; Taylor, P.N.; Mason, J.; Sattar, N.; McMurray, J.J.; McInnes, I.B. Incidence, Prevalence, and Co-Occurrence of Autoimmune Disorders Over Time and by Age, Sex, and Socioeconomic Status: A Population-Based Cohort Study of 22 million Individuals in the UK. Lancet 2023, 401, 1878–1890.

- Li, L.; Xu, H.; Qu, L.; Nisar, M.; Farrukh Nisar, M.; Liu, X.; Xu, K. Water extracts of Polygonum Multiflorum Thunb. and its active component emodin relieves osteoarthritis by regulating cholesterol metabolism and suppressing chondrocyte inflammation. Acupunct. Herb. Med. 2023, 3, 96–106.

- Abidullah, S.; Rauf, A.; Zaman, W.; Ullah, F.; Ayaz, A.; Batool, F.; Saqib, S. Consumption of wild food plants among tribal communities of Pak-Afghan border, near Bajaur, Pakistan. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 254–270.

- Calixto, J.B. Twenty-Five Years of Research on Medicinal Plants in Latin America: A Personal View. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 131–134.

- Zaman, W.; Ye, J.; Saqib, S.; Liu, Y.; Shan, Z.; Hao, D.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, P. Predicting potential medicinal plants with phylogenetic topology: Inspiration from the research of traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 281, 114515.

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs Over the Last 25 Years. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 461–477.

- Schippmann, U.; Leaman, D.J.; Cunningham, A.B. Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity: Global Trends and Issues. In Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002.

- Kesharwani, V.; Gupta, S.; Kushwaha, N.; Kesharwani, R.; Patel, D.K. A review on therapeutics application of eucalyptus oil. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 6, 110–115.

- Turnbull, J. Eucalypts in China. Aust. For. 1981, 44, 222–234.

- Silva-Pando, F.; Pino-Pérez, R. Introduction of Eucalyptus into Europe. Aust. For. 2016, 79, 283–291.

- Vuong, Q.V.; Chalmers, A.C.; Jyoti Bhuyan, D.; Bowyer, M.C.; Scarlett, C.J. Botanical, phytochemical, and anticancer properties of the Eucalyptus species. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 907–924.

- Rozefelds, A. Eucalyptus Phylogeny and History: A Brief Summary. Tasforests 1996, 8, 15–26.

- Hill, K.D.; Johnson, L.A. Systematic Studies in the Eucalypts 7. A Revision of the Bloodwoods, genus Corymbia (Myrtaceae). Telopea 1995, 6, 185–504.

- Locher, C.; Currie, L. Revisiting Kinos—An Australian Perspective. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 128, 259–267.

- Marinkovic, J.; Markovic, T.; Nikolic, B.; Soldatovic, I.; Ivanov, M.; Ciric, A.; Sokovic, M.; Markovic, D. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Potential of Leptospermum petersonii F.M.Bailey, Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. Pelargonium graveolens L′Hér. and Pelargonium roseum (Andrews) DC. Essential Oils Against Selected Dental Isolates. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2021, 24, 304–316.

- Senadeera, S.P.D.; Robertson, L.P.; Duffy, S.; Wang, Y.; Avery, V.M.; Carroll, A.R. β-Triketone-Monoterpene Hybrids from the Flowers of the Australian Tree Corymbia intermedia. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 2455–2461.

- Al-Sayed, E.; El-Naga, R.N. Protective Role of Ellagitannins from Eucalyptus citriodora Against Ethanol-Induced Gastric Ulcer in Rats: Impact on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Calcitonin-Gene Related Peptide. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 5–15.

- Ansari, P.; Choudhury, S.T.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Insulin Secretory Actions of Ethanol Extract of Eucalyptus citriodora Leaf, Including Plasma DPP-IV and GLP-1 Levels in High-Fat-Fed Rats, as Well as Characterization of Biologically Effective Phytoconstituents. Metabolites 2022, 12, 757.

- Smith, N.M. Ethnobotanical Field Notes from The Northern Territory, Australia. J. Adel. Bot. Gard. 1991, 14, 1–65.

- Bignell, C.; Dunlop, P.; Brophy, J. Volatile Leaf Oils of Some Queensland and Northern Australian Species of the Genus Eucalyptus (series II). Part II. Subgenera (a) Blakella, (b) Corymbia, (c) Unnamed, (d) Idiogenes, (e) Monocalyptus and (f) Symphyomyrtus. Flavour Fragr. J. 1997, 12, 277–284.

- Hills, W.E. The Chemistry of Eucalypt Kinos. II. Aromadendrin, Kaempferol, and Ellagic acid. Aust. J. Chem. 1952, 5, 379–386.

- White, D.E.; Zampatti, L.S. The Chemistry of Western Australian Plants. Part VII.* Oleanolic Acid Acetate from Eucalyptus calophylla Bark. J. Chem. Soc. 1952, 4996–5000.

- Hillis, W.E.; Carle, A. The Chemistry of Eucalypt Kinos. III. (+)-Afzelechin, Pyrogallol, and (+)-Catechin from Eucalyptus calophylla Kino. Aust. J. Chem. 1960, 13, 390–395.

- Ganguly, A.K.; Seshadri, T.R. 543. Leucoanthocyanidins of Plants. Part III. Leucopelargonidin from Eucalyptus calophylla Kino. J. Chem. Soc. 1961, 2787–2790.

- Bedi Sahouo, G.; Tonzibo, Z.F.; Boti, B.; Chopard, C.; Mahy, J.P.; N’Guessan, Y.T. Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Activities: Chemical Constituents of Essential Oils of Ocimum gratissimum, Eucalyptus citriodora and Cymbopogon giganteus Inhibited Lipoxygenase L-1 and Cyclooxygenase of PGHS. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2003, 17, 191–197.

- Ayinde, B.A.; Owolabi, O.J. Inhibitory Effects of the Volatile Oils of Callistemon citrinus (Curtis) Skeels and Eucalyptus citriodora Hook (Myrtaceae) on the Acetylcholine Induced Contraction of Isolated Rat Ileum. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 25, 435–439.

- Bhuyan, D.J.; Vuong, Q.V.; Bond, D.R.; Chalmers, A.C.; van Altena, I.A.; Bowyer, M.C.; Scarlett, C.J. Exploring the Least Studied Australian Eucalypt Genera: Corymbia and Angophora for Phytochemicals with Anticancer Activity Against Pancreatic Malignancies. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600291.

- Gopan, R.; Renju, K.V.; Pradeep, N.S.; Sabulal, B. Volatile Oil of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook, from South India: Chemistry and Antibacterial Activity. Int. J. Essent. Oil Ther. 2009, 3, 147–151.

- Hung, W.J.; Chen, Z.T.; Lee, S.W. Antioxidant and Lipoxygenase Inhibitory Activity of the Kino of Eucalyptus citriodora. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 80, 955–959.

- Salem, M.Z.M.; Elansary, H.O.; Ali, H.M.; El-Settawy, A.A.; Elshikh, M.S.; Abdel-Salam, E.M.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K. Bioactivity of Essential Oils Extracted from Cupressus macrocarpa Branchlets and Corymbia citriodora Leaves Grown in Egypt. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 23.

- Ribeiro, R.V.; Bieski, I.G.C.; Balogun, S.O.; Martins, D.T.D.O. Ethnobotanical study of Medicinal Plants Used by Ribeirinhos in the North Araguaia Microregion, Mato Grosso, Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 205, 69–102.

- Silva, J.; Abebe, W.; Sousa, S.M.; Duarte, V.G.; Machado, M.I.L.; Matos, F.J.A. Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Essential Oils of Eucalyptus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 277–283.

- Koudoro, Y.A.; Agbangnan Dossa, C.P.; Yèhouénou, B.B.; Tchobo, F.P.; Alitonou, G.A.; Avlessi, F.; Sohounhloué, D.C.K. Phytochemistry, Antimicrobial and Antiradical Activities Evaluation of Essential Oils, Ethanolic and Hydroethanolic Extracts of the Leaves of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. from Benin. Sci. St. Res. Chem. Chem. Eng. Biotechnol. Food Ind. 2014, 15, 59–73.

- Mishra, M.P.; Padhy, R.N. In vitro Antibacterial Efficacy of 21 Indian Timber-Yielding Plants Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Causing Urinary Tract Infection. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2013, 4, 347–357.

- Akin-Osanaiye, B.C.; Agbaji, A.S.; Dakare, M.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Oils and Extracts of Cymbopogon citratus (Lemon Grass), Eucalyptus citriodora and Eucalyptus camaldulensis. J. Med. Sci. 2007, 7, 694–697.

- Yu, Q.; Feng, Z.; Huang, L.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, F. Ellagic Acid (EA), a Tannin was Isolated from Eucalyptus citriodora Leaves and its Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 2277–2288.

- Duh, P.D.; Chen, Z.T.; Lee, S.W.; Lin, T.P.; Wang, Y.T.; Yen, W.J.; Kuo, L.F.; Chu, H.L. Antiproliferative Activity and Apoptosis Induction of Eucalyptus citriodora Resin and its Major Bioactive Compound in Melanoma B16F10 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 7866–7872.

- Shen, K.H.; Chen, Z.T.; Duh, P.D. Cytotoxic Effect of Eucalyptus citriodora Resin on Human Hepatoma HepG2 Cells. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2012, 40, 399–413.

- Anet, E.F.L.J.; Birch, A.J.; Massy-Westropp, R.A. The Isolation of Shikimic Acid from Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. Aust. J. Chem. 1957, 10, 93–94.

- Barasa, S.S.; Ndiege, I.O.; Lwande, W.; Hassanali, A. Repellent Activities of Stereoisomers of p-Menthane-3,8-diols Against Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2002, 39, 736–741.

- El-Sakhawy, M.A.; Soliman, G.A.; El-Sheikh, H.H.; Ganaie, M.A. Anticandidal Effect of Eucalyptus Oil and Three Isolated Compounds on Cutaneous Wound Healing in Rats. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. 2023, 27, 26–37.

- Freitas, M.O.; Lima, M.A.S.; Silveira, E.R. NMR Assignments of Unusual Flavonoids from the Kino of Eucalyptus citriodora. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2007, 45, 262–264.

- Freitas, M.O.; Lima, M.A.S.; Silveira, E.R. Polyphenol Compounds of the Kino of Eucalyptus citriodora. Quim. Nova 2007, 30, 1926–1929.

- He, Y.; Shang, Q.; Tian, L. A New Triterpenoid and Potential Anticancer Cytotoxic Activity of Isolated Compounds from the Roots of Eucalyptus citriodora. J. Chem. Res. 2015, 39, 70–72.

- Lee, C.K.; Chang, M.H. The Chemical Constituents from the Heartwood of Eucalyptus citriodora. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2000, 47, 555–560.

- Lee, S.W.; Hung, W.J.; Chen, Z.T. A New Flavonol from the Kino of Eucalyptus citriodora. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 37–42.

- Lin, S.Q.; Zhou, Z.L.; Yin, W.Q. Three New Polyphenolic Acids from the Leaves of Eucalyptus citriodora with Antivirus Activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 1641–1646.

- Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhou, Q.; Mei, Z.; Yang, G.; Yang, X.; Feng, Y. Chemical Constituents from Eucalyptus citriodora Hook Leaves and their Glucose Transporter 4 Translocation Activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3096–3099.

- Zou, X.; Huang, D.; Zhou, C.; Li, L.; Chen, K.; Guo, Z.; Lin, S.; Yin, W.; Zhou, Z. A New Flavonoid Glycoside from the Leaves of Eucalyptus citriodora. J. Chem. Res. 2014, 38, 532–534.

- Zhou, Z.L.; Yin, W.Q.; Zou, X.P.; Huang, D.Y.; Zhou, C.L.; Li, L.M.; Chen, K.C.; Guo, Z.Y.; Lin, S.Q. Flavonoid Glycosides and Potential Antivirus Activity of Isolated Compounds from the Leaves of Eucalyptus citriodora. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2014, 57, 813–817.

- Satwalekar, S.; Gupta, T.; Narasimharao, P. Chemical and Antibacterial Properties of Kino from Eucalyptus spp. Citriodorol—The Antibiotic Principle from the Kino of E. Citriodora. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 1957, 39, 195–212.

- Cavalcanti, A.L.; Aguiar, Y.P.C.; Santos, F.G.D.; Cavalcanti, A.F.C.; De Castro, R.D. Susceptibility of Candida albicans and Candida non-albicans Strains to Essential Oils. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2017, 10, 1101–1107.

- Tolba, H.; Moghrani, H.; Benelmouffok, A.; Kellou, D.; Maachi, R. Essential Oil of Algerian Eucalyptus citriodora: Chemical Composition, Antifungal Activity. J. Mycol. Med. 2015, 25, e128–e133.

- Gupta, S.; Bhagat, M.; Sudan, R.; Dogra, S.; Jamwal, R. Comparative Chemoprofiling and Biological Potential of Three Eucalyptus Species Growing in Jammu and Kashmir. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2015, 18, 409–415.

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, K. Efficacy of Lawsonia inermis Linn. and Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. Extracts as Inhibitors of Growth and Enzymatic Activity of Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. J. Biol. Act. Prod. Nat. 2011, 1, 168–182.

- Udaya Prakash, N.K.; Bhuvaneswari, S.; Sripriya, N.; Arulmozhi, R.; Kavitha, K.; Aravitha, R.; Bharathiraja, B. Studies on Phytochemistry, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Larvicidal and Pesticidal Activities of Aromatic Plants from Yelagiri Hills. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 325–328.

- Su, Y.C.; Hsu, K.P.; Ho, C.L. Composition, in vitro Antibacterial and Anti-Mildew Fungal Activities of Essential Oils from Twig and Fruit Parts of Eucalyptus citriodora. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 1647–1650.

- Da Cruz, J.E.R.; Da Costa Guerra, J.F.; De Souza Gomes, M.; Freitas, G.R.O.; Morais, E.R. Phytochemical Analysis and Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Peumus boldus, Psidium guajava, Vernonia polysphaera, Persea americana, Eucalyptus citriodora Leaf Extracts and Jatropha multifida Raw Sap. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 433–444.

- Ramos Alvarenga, R.F.; Wan, B.; Inui, T.; Franzblau, S.G.; Pauli, G.F.; Jaki, B.U. Airborne Antituberculosis Activity of Eucalyptus citriodora Essential Oil. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 603–610.

- Zheng, X.; Feyaerts, A.F.; Dijck, P.V.; Bossier, P. Inhibitory Activity of Essential Oils Against Vibrio campbellii and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1946.

- Zheng, X.; Han, B.; Kumar, V.; Feyaerts, A.F.; Van Dijck, P.; Bossier, P. Essential Oils Improve the Survival of Gnotobiotic Brine Shrimp (Artemia franciscana) Challenged with Vibrio campbellii. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 693932.

- Clemente, M.A.; De Oliveira Monteiro, C.M.; Scoralik, M.G.; Gomes, F.T.; De Azevedo Prata, M.C.; Daemon, E. Acaricidal Activity of the Essential Oils from Eucalyptus citriodora and Cymbopogon nardus on Larvae of Amblyomma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae) and Anocentor nitens (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasitol. Res. 2010, 107, 987–992.

- Rodrigues, L.; Giglioti, R.; Gomes, A.C.P.; Katiki, L.M.; Otsuk, I.P.; da Silva Matos, R.; Nodari, E.F.; Veríssimo, C.J. In vitro Effect of Volatile Substances from Eucalyptus Oils on Rhipicephalus microplus. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2020, 30, 737–742.

- Habila, N.; Agbaji, A.S.; Ladan, Z.; Bello, I.A.; Haruna, E.; Dakare, M.A.; Atolagbe, T.O. Evaluation of in vitro Activity of Essential Oils Against Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma evansi. J. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 2010, 534601.

- Silva Maiolini, T.C.; Rosa, W.; de Oliveira Miranda, D.; Costa-Silva, T.A.; Tempone, A.G.; Pires Bueno, P.C.; Ferreira Dias, D.; Aparecida Chagas de Paula, D.; Sartorelli, P.; Lago, J.H.G.; et al. Essential Oils from Different Myrtaceae Species from Brazilian Atlantic Forest Biome–Chemical Dereplication and Evaluation of Antitrypanosomal Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202200198.

- Jain, S.; Jacob, M.; Walker, L.; Tekwani, B. Screening North American Plant Extracts in vitro Against Trypanosoma brucei for Discovery of New Antitrypanosomal Drug Leads. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 131.

- Singh, N.; Kaushik, N.K.; Mohanakrishnan, D.; Tiwari, S.K.; Sahal, D. Antiplasmodial Activity of Medicinal Plants from Chhotanagpur Plateau, Jharkhand, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 165, 152–162.

- Park, I.L.K.; Shin, S.C. Fumigant Activity of Plant Essential Oils and Components from Garlic (Allium sativum) and Clove Bud (Eugenia caryophyllata) Oils Against the Japanese Termite (Reticulitermes speratus Kolbe). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4388–4392.

- Vera, S.S.; Zambrano, D.F.; Méndez-Sanchez, S.C.; Rodríguez-Sanabria, F.; Stashenko, E.E.; Duque Luna, J.E. Essential Oils with Insecticidal Activity against Larvae of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 2647–2654.

- Singh, R.K.; Dhiman, R.C.; Mittal, P.K. Studies on Mosquito Larvicidal Properties of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook (Family-Myrtaceae). J. Commun. Dis. 2007, 39, 233–236.

- Cruz, G.S.; Wanderley-Teixeira, V.; da Silva, L.M.; Dutra, K.A.; Guedes, C.A.; de Oliveira, J.V.; Navarro, D.M.A.F.; Araújo, B.C.; Teixeira, Á.A.C. Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Activity of the Essential Oils of Foeniculum vulgare Mill. Ocimum basilicum L. Eucalyptus staigeriana F. Muell. ex Bailey, Eucalyptus citriodora Hook and Ocimum gratissimum L. and Their Major Components on Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2017, 20, 1360–1369.

- Sahi, N.M. Evaluation of Insecticidal Activity of Bioactive Compounds from Eucalyptus citriodora Against Tribolium castaneum. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2016, 8, 1256–1270.

- Ghareeb, M.A.; Refahy, L.A.; Saad, A.M.; Ahmed, W.S. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities of the Essential Oil from Eucalyptus citriodora (Hook.) Leaves. Der Pharma Chem. 2016, 8, 192–200.

- Chahomchuen, T.; Insuan, O.; Insuan, W. Chemical Profile of Leaf Essential Oils from Four Eucalyptus Species from Thailand and Their Biological Activities. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105248.

- Jirovetz, L.; Bail, S.; Buchbauer, G.; Stoilova, I.; Krastanov, A.; Stoyanova, A.; Stanchev, V.; Schmidt, E. Chemical Composition, Olfactory Evaluation and Antioxidant Effects of the Leaf Essential Oil of Corymbia citriodora (Hook) from China. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 599–606.

- Zhao, Q.; Bowles, E.J.; Zhang, H.Y. Antioxidant Activities of Eleven Australian Essential Oils. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 837–842.

- Arjun, P.; Shivesh, J.; Alakh, N.S. Antidiabetic Activity of Aqueous Extract of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. in Alloxan Induced Diabetic Rats. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2009, 5, 51–54.

- Ak Sakallı, E.; Teralı, K.; Karadağ, A.E.; Biltekin, S.N.; Koşar, M.; Demirci, B.; Hüsnü Can Başer, K.; Demirci, F. In vitro and in silico Evaluation of ACE2 and LOX Inhibitory Activity of Eucalyptus Essential Oils, 1,8-Cineole, and Citronellal. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17, 1934578X221109409.

- Ho, C.L.; Li, L.H.; Weng, Y.C.; Hua, K.F.; Ju, T.C. Eucalyptus Essential Oils Inhibit the Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response in RAW264.7 Macrophages Through Reducing MAPK and NF-κB Pathways. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 200.

- Ansari, P.; Flatt, P.R.; Harriott, P.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Insulinotropic and Antidiabetic Properties of Eucalyptus citriodora Leaves and Isolation of Bioactive Phytomolecules. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 1049–1061.

- Miguel, M.G.; Gago, C.; Antunes, M.D.; Lagoas, S.; Faleiro, M.L.; Megías, C.; Cortés-Giraldo, I.; Vioque, J.; Figueiredo, A.C. Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Antiproliferative Activities of Corymbia citriodora and the Essential Oils of Eight Eucalyptus Species. Medicines 2018, 5, 61.

- Koundal, R.; Kumar, D.; Walia, M.; Kumar, A.; Thakur, S.; Chand, G.; Padwad, Y.S.; Agnihotri, V.K. Chemical and in vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Essential Oil from Eucalyptus citriodora Fruits Growing in the Northwestern Himalaya, India. Flavour Fragr. J. 2016, 31, 158–162.

- Iram, W.; Anjum, T.; Iqbal, M.; Ghaffar, A.; Abbas, M. Mass Spectrometric Identification and Toxicity Assessment of Degraded Products of Aflatoxin B1 and B2 by Corymbia citriodora Aqueous Extracts. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14672.

- Hadis, M.; Lulu, M.; Mekonnen, Y.; Asfaw, T. Field Trials on the Repellent Activity of Four Plant Products Against Mainly Mansonia Population in Western Ethiopia. Phytother. Res. 2003, 17, 202–205.

- Siddique, Y.H.; Mujtaba, S.F.; Jyoti, S.; Naz, F. GC-MS Analysis of Eucalyptus citriodora Leaf Extract and its Role on the Dietary Supplementation in Transgenic Drosophila Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 29–35.

- Reid, E.J.; Betts, T. Records of Western Australian Plants Used by Aboriginals as Medicinal Agents. Planta Med. 1979, 36, 164–173.

- Akhtar, M.A.; Raju, R.; Beattie, K.D.; Bodkin, F.; Münch, G. Medicinal Plants of the Australian Aboriginal Dharawal People Exhibiting Anti-Inflammatory Activity. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 2935403.

- Turpin, G.; Ritmejerytė, E.; Jamie, J.; Crayn, D.; Wangchuk, P. Aboriginal Medicinal Plants of Queensland: Ethnopharmacological Uses, Species Diversity, and Biodiscovery Pathways. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 1–15.

- Packer, J.; Brouwer, N.; Harrington, D.; Gaikwad, J.; Heron, R.; Yaegl Community, E.; Ranganathan, S.; Vemulpad, S.; Jamie, J. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by the Yaegl Aboriginal Community in Northern New South Wales, Australia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 244–255.

- Packer, J.; Naz, T.; Harrington, D.; Jamie, J.F.; Vemulpad, S.R. Antimicrobial Activity of Customary Medicinal Plants of the Yaegl Aboriginal community of Northern New South Wales, Australia: A Preliminary Study. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 276.

- von Martius, S.; Hammer, K.A.; Locher, C. Chemical Characteristics and Antimicrobial Effects of Some Eucalyptus Kinos. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 144, 293–299.

- Cornwell, C.P.; Reddy, N.; Leach, D.N.; Grant Wyllie, S. Germacradienols in the Essential Oils of the Myrtaceae. Flavour Fragr. J. 2001, 16, 263–273.

- Sidana, J.; Neeradi, D.; Choudhary, A.; Singh, S.; Foley, W.J.; Singh, I.P. Antileishmanial Polyphenols from Corymbia maculata. J. Chem. Sci. 2013, 125, 765–775.

- Gell, R.J.; Pinhey, J.T.; Ritchie, E. The Constituents of the Kino of Eucalyptus maculata Hook. Aust. J. Chem. 1958, 11, 372–375.

- Mishra, C.S.; Misra, K. Chemical Examination of the Stem Bark of Eucalyptus maculata. Planta Med. 1980, 38, 169–173.

- Abdel-Sattar, E.; Kohiel, M.A.; Shihata, I.A.; El-Askary, H. Phenolic Compounds from Eucalyptus maculata. Pharmazie 2000, 55, 623–624.

- Rashwan, O.A. New Phenylpropanoid Glucosides from Eucalyptus maculata. Molecules 2002, 7, 75–80.

- Ebiloma, G.U.; Igoli, J.O.; Katsoulis, E.; Donachie, A.M.; Eze, A.; Gray, A.I.; de Koning, H.P. Bioassay-Guided Isolation of Active Principles from Nigerian Medicinal Plants Identifies New Trypanocides with Low Toxicity and No Cross-Resistance to Diamidines and Arsenicals. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 202, 256–264.

- Ali, D.E.; Abdelrahman, R.S.; El Gedaily, R.A.; Ezzat, S.M.; Meselhy, M.R.; Abdelsattar, E. Evaluation of the Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities of Selected Resin Exudates. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 4, 255–261.

- Mohamed, A.F.; Ali Hasan, A.G.; Hamamy, M.I.; Abdel-Sattar, E. Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Eucalyptus maculata. Med. Sci. Monit. 2005, 11, BR426–BR431.

- Hart, N.; Lamberton, J. Morolic acid (3-Hydroxyolean-18-en-28-oic acid) From the Bark of Eucalyptus papuana F. Muell. Aust. J. Chem. 1965, 18, 115–116.

- Silou, T.; Loumouamou, A.N.; Loukakou, E.; Chalchat, J.C.; Figuérédo, G. Intra and Interspecific Variations of Yield and Chemical Composition of Essential Oils from Five Eucalyptus Species Growing in the Congo-Brazzaville. Corymbia subgenus. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 203–211.

- Silou, T.; Loumouamou, A.N.; Makany, A.R.; Dembi, F.; Figuérédo, G.; Chalchat, J.-C. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the Variability of Essential Oils from the Leaves of Eucalyptus torelliana Acclimatised in Congo-Brazzaville. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2010, 13, 503–514.

- Panahi, Y.; Sattari, M.; Babaie, A.P.; Beiraghdar, F.; Ranjbar, R.; Bigdeli, M. The Essential Oils Activity of Eucalyptus polycarpa, E. largiflorence, E. malliodora and E. camaldulensis on Staphylococcus aureus. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 10, 43–48.

- Edward, H.G.M.; de Oliveira, L.F.C.; Quye, A. Raman Spectroscopy of Coloured Resins Used in Antiquity: Dragon’s Blood and Related Substances. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2001, 57, 2831–2842.

- Brophy, J.J.; Forster, P.I.; Goldsack, R.J.; Brynn Hibbert, D. The Essential Oils of the Yellow Bloodwood Eucalypts (Corymbia, section Ochraria, Myrtaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1998, 26, 239–249.

- Adeniyi, C.B.A.; Lawal, T.O.; Mahady, G.B. In vitro Susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to Extracts of Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus torelliana. Pharm. Biol. 2009, 47, 99–102.

- Silifat, J.T.; Ogunwande, I.A.; Olawore, N.O.; Walker, T.M.; Schmidt, J.M.; Setzer, W.N.; Olaleye, O.N.; Aboaba, S.A. In vitro Cytotoxicity Activitie of Essential Oils of Eucalyptus torreliana F. v. Muell (Leaves and Fruits). J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2005, 8, 110–119.

- Senadeera, S.P.D.; Lucantoni, L.; Duffy, S.; Avery, V.M.; Carroll, A.R. Antiplasmodial β-Triketone-Flavanone Hybrids from the Flowers of the Australian Tree Corymbia torelliana. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 1588–1597.

- Sutherland, M.; Webb, L.; Wells, J. Terpenoid Chemistry. III. The Essential Oils of Eucalyptus deglupta Blume and E. torelliana F. Muell. Aust. J. Chem. 1960, 13, 357–366.

- Lamberton, J.A. The Occurrence of 5-Hydroxy-7,4’-dimethoxy-6-methylflavone in Eucalyptus Waxes. Aust. J. Chem. 1964, 17, 692–696.

- Lawal, T.O.; Adeniyi, B.A.; Adegoke, A.O.; Franzblau, S.G.; Mahady, G.B. In vitro Susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to Extracts of Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus torelliana and Isolated Compounds. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 92–98.

- Massaro, C.F.; Katouli, M.; Grkovic, T.; Vu, H.; Quinn, R.J.; Heard, T.A.; Carvalho, C.; Manley-Harris, M.; Wallace, H.M.; Brooks, P. Anti-Staphylococcal Activity of C-Methyl Flavanones from Propolis of Australian Stingless Bees (Tetragonula carbonaria) and Fruit Resins of Corymbia torelliana (Myrtaceae). Fitoterapia 2014, 95, 247–257.

- Nobakht, M.; Grkovic, T.; Trueman, S.J.; Wallace, H.M.; Katouli, M.; Quinn, R.J.; Brooks, P.R. Chemical Constituents of Kino Extract from Corymbia torelliana. Molecules 2014, 19, 17862–17871.

- Adeniyi, B.; Odufowoke, R.; Olaleye, S. Antibacterial and Gastroprotective Properties of Eucalyptus torelliana Crude Extracts. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 2, 362–365.

More