You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Heba Alzan.

Piroplasmosis is a global tick-borne disease caused by hemoprotozoan parasites, which causes high morbidity and substantial economic losses in farm animals. Equine and camel piroplasmosis causes significant losses worldwide and in Egypt. The multifactorial effects and overall impact of equine and camel piroplasmosis in Egypt remain poorly characterized.

- equine

- camel

- piroplasma

- Babesia

- tick

- tick borne diseases

- Theileria

- diagnosis

1. An Overview of tThe Equine and Camel Industry in Egypt

The estimated current sizes of the target animal populations in Egypt include 120,000 camels and 85,000 horses [4,22][1][2].

1.1. Equines

About 230 farms in Egypt specialize in raising Arabian horses, and the Egyptian Agricultural Authority offers pedigree certifications for all horses sold to foreign nations that go back up to six generations, in addition to permanently marking all animals they possess (Freeze Marking). Also, a single office creates the formal documents required for export activities.

In Egypt, a number of horse breeders from various nations are invited to a competition that is held every year in the month of November. This event has a number of equestrian competitions and shows that are judged by an international committee. The organization of international festivals and contests that take place in Egypt has an important economic impact, since numerous visitors from foreign countries, including neighboring Arabic countries, are usually interested in attending these events, which also refreshes the tourist industry and drives horse trading [23][3].

Additionally, in many rural areas of Egypt, horses, donkeys, mules, and ponies are often used as working equids. These animals assist personnel in a variety of sectors, including agriculture and construction, help farmers in soil drilling and public transportation, and contribute to sustaining the livelihoods of millions of people [5,6][4][5].

1.2. Camels

Three species of camels can be found in Egypt: the one-humped Arabian camel [also known as dromedaries] (Camelus dromedarius), the Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus), which is a two-humped camel, and its wild counterpart (Camelus ferus) [19,24,25,26][6][7][8][9]. The one-humped camel Camelus dromedarius, or dromedary, is a domestic animal belonging to the Camelidae family and is widely distributed in the arid and semi-arid regions of Africa, Arabia, and western Asia, extending up to India [8][10]. The world’s current camel population is about 28 million heads, and 80% of them live in Africa, with 60% in the Horn of Africa. Arabian camels (Dromedaries) constitute 94% of the world’s camel population [22,27][2][11]. In Egypt, there are four distinct camel breeds, belonging to Camelus dromedarius, which differ phenotypically: the Sudani (often used for riding and racing), the Falahi or Baladi (used for transportation and agricultural work), the Maghrabi (used for both meat and milk), and the Mowallad (a hybrid of the two) [28][12].

Arabian camels significantly contribute to Egypt’s local economy and culture. They do so by producing milk and meat for human consumption, as well as wool. Regarding camel milk production, unfortunately in Egypt, camel milk is underestimated, and it does not seem to contribute significantly to the economy of the country [28][12], despite its high nutritional value. The camel contribution to meat production started to increase not only in Egypt but also in other developing countries [10][13], given the fact that camels are likely to have disease-resistance traits [28][12]. Additionally, camels serve as a mode of transportation, particularly in the desert which is widely distributed in Egypt; therefore, they are an important component of nomadic life. Camel rearing is primarily practiced for recreational and entertainment purposes in tourist areas such as the Luxor and Red Sea governorates [20][14]. In addition, camel racing is considered a popular traditional sport in many Arab countries, most notably in the Gulf region, and in Egypt, Bedouins of the South Sinai desert have kept up this tradition. To the Bedouins, the race is a way of keeping a traditional heritage alive. This race is considered an ancestral heritage and they are trying to preserve and renew it to hand it over from one generation to the next, which has been ongoing for at least the last 100 years [29][15].

Smallholders occasionally raise camels in the countryside, together with other animals, or on their own farms. They can also do so in desert pastures like those in the Sinai Peninsula, the northwest coastal region, and the Red Sea coast [18][16]. Between 2012 and 2015, Sudan and Ethiopia were the major sources of camels for Egypt, with more than 750,000 camel imports during this time [19,30][6][17]. In fact, the Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO] recorded an increase in the camel population in Egypt from 111,000 in 2010 to about 149,500 in 2017 [28][12]. Notably, Egypt needs to import large numbers of live camels because the high rate of slaughtering is resulting in the fast depletion of the stock of available animals [28][12].

2. Impact of Equine and Camel Piroplasmosis in Egypt

Since equines and camels are currently important resources for recreation and food production in Egypt, maintaining healthy populations of these species is critical. This diminishes the chances for the expansion of emerging zoonotic agents, such as Babesia microti and B. divergens, which may impact human health and create improved economic environments for the producers. In addition, uncontrolled camel piroplasmosis is also a threat to the production of critical food resources that can sustain the current high population growth rates in Egypt.

2.1. Equines

In rural areas of Egypt, the health and welfare of domestic equines are often neglected despite the high risk of contracting many infectious diseases, including African horse sickness, epizootic lymphangitis (EZL), rabies, trypanosomiasis, and piroplasmosis. Knowledge about the identification, management, and prevention of different infectious diseases is lacking in general [31][18].

Equine piroplasmosis, recognized as one of the most frequent infectious tick-borne diseases (TBDs) in equids, is caused by the hemoprotozoan parasites T. equi, B. caballi, and the newly identified species T. haneyi [12,13][19][20]. It is possible, however, that additional and likely lowly virulent equine Babesia and Theileria species will be identified in the future. Infections with T. equi and B. caballi cause severe economic losses in the equine industry due to the cost of treatment, especially in acutely infected horses. Additionally, the absence of appropriate treatments can lead to the death of the animals [6][5], and the infected and carrier equines are a common source of infection for ticks and other animals [16][21].

Importantly, EP manifests as acute and persistent infections. Clinical signs are not specific to EP and vary from lacking to severe, whereas signs in acute cases are characterized by fever, anemia, hemoglobinuria, jaundice, edema, and even death [32][22]. Furthermore, and because EP is also characterized by persistent infections, horses and donkeys may act as carriers for many years, particularly after T. equi infection [33][23]. It was found that T. haneyi causes milder clinical disease (variable fever, anemia) than T. equi in experimentally infected horses and is capable of superinfection with T. equi [34][24]. After the acute phase of the disease, asymptomatic horses may continue to be infected and these asymptomatic horses may become reservoirs of infectious organisms for the appropriate vectors of ticks [35][25]. Unfortunately, T. haneyi does not appear to be susceptible to imidocarb diproprionate (ID), although most equine infections with U.S. strains of T. equi can be treated with ID, and co-infections of horses with T. equi and T. haneyi reduce the effectiveness of ID against T. equi. So, the global importance of T. haneyi to equine health was recently shown through its resistance to ID and its interference with T. equi clearance by ID in some co-infected horses [34][24].

2.2. Camels

Although camels can tolerate harsh conditions, they can also be affected by climatic changes and by infections with different infectious diseases, including those caused by vector-borne hemopathogens, which frequently compromise the health and production of camels [20][14].

Camel piroplasmosis (CP) is an acute to chronic infectious disease with a worldwide distribution that causes high morbidity and substantial economic losses [18][16]. Similar to EP, CP can be caused by several Theileria and Babesia parasites, including T. equi, B. caballi, B. bovis, B. bigemina, among others [17][26]. Clinical symptoms include anemia, hemoglobinuria, muscle trembling, and decreases in body temperature to a subnormal level a few hours of before death in untreated cases [36][27].

Camel babesiosis, caused by several tick-borne Babesia sp., is marked by severe morbidity and substantial economic loss [15][28]. There is a lack of information about camel infections caused by Babesia species, which are of zoonotic importance in Egypt. One of the most significant Babesia species that affects humans is Babesia microti, which may spread through blood transfusion or organ transplantation [37][29]. Using molecular diagnostic methods and phylogenetic analysis of the discovered parasite, some researchers found B. microti infections in camel breeds in Halayeb and Shalateen in Upper Egypt [9][30]. This was a significant finding because the possible existence of camel reservoirs may represent a potential zoonotic risk to other animals and humans. In contrast to other animals, there is little knowledge of camels’ involvement in sustaining zoonotic tick-borne pathogens (TBPs), despite the importance of camels to human life in the country [9][30].

3. Historical Overview of Equine and Camel Piroplasmosis in Egypt

3.1. Equine

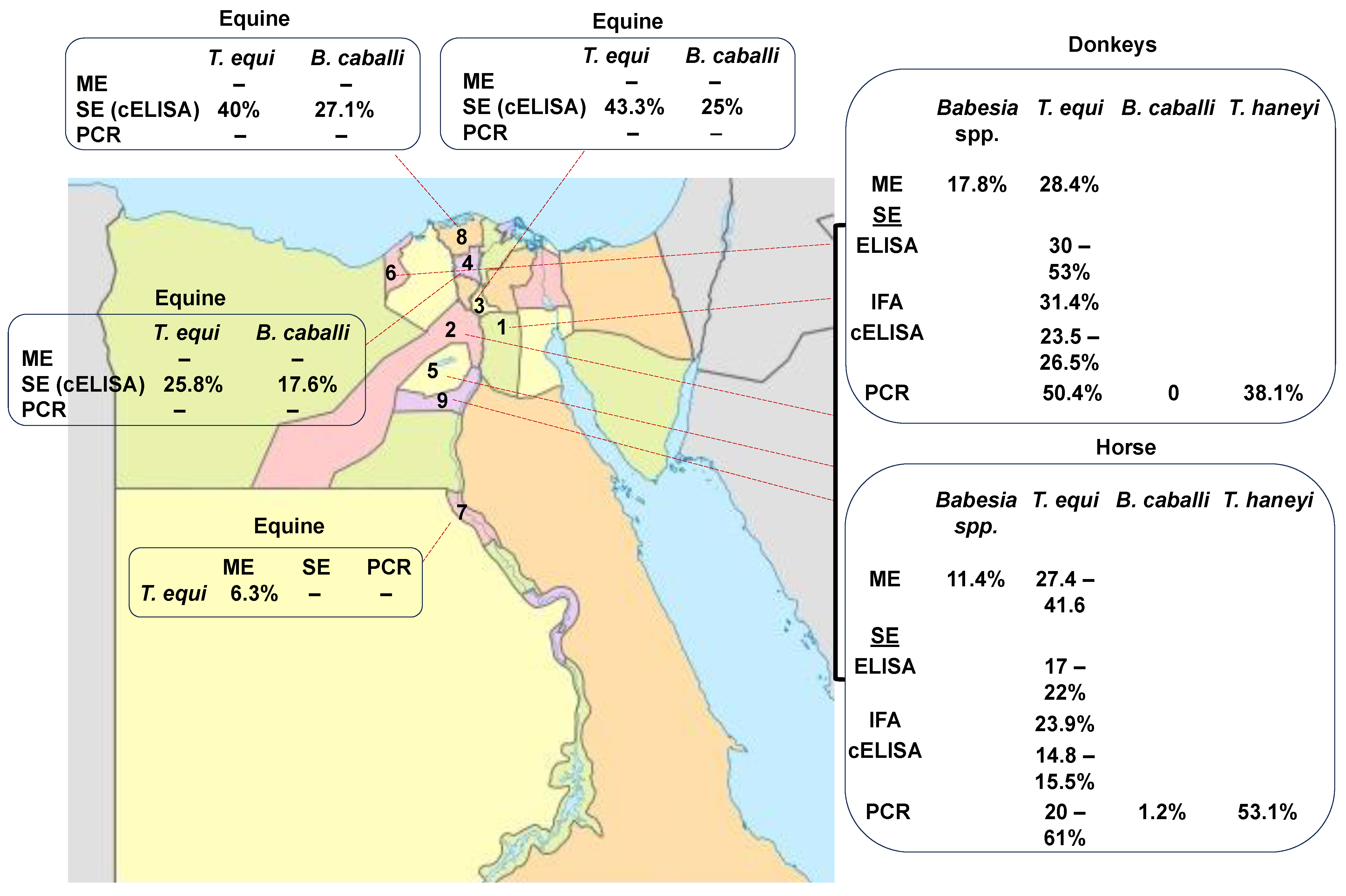

Equine piroplasmosis has been currently reported in different geographic regions of Egypt (Assiut, Cairo, Giza, Qalubia, Kafr Elshiekh, Menofia, Alexandria, Ismailia, Faiyum, Al-Beheira, Matruh, and Beni Suef) (Figure 1). In the past, the detection of the piroplasms in Egypt depended mainly on ME [52][31]. After that, serological studies based on IFAT revealed exposure of equines to T. equi [44,53][32][33] and B. caballi parasites [44][32] in the Cairo and Giza regions of Egypt. More sensitive serological methods, such as indirect (i) ELISA, also revealed the presence of T. equi in horses and donkeys in Egypt [44,45,54][32][34][35]. In addition, a competitive (c) ELISA based on the EMA-1 recombinant protein revealed the presence of T. equi in horses and donkeys. However, a cELISA based on RAP-1 failed to detect B. caballi in Egyptian equines in Cairo and Giza [44][32], as well as in South Africa, [55][36]. Possibly, given the sequence variability found among the B. caballi RAP-1 proteins among distinct strains from different countries, it is possible that RAP-1-based serological methods, as currently designed, are not capable of effectively detecting B. caballi infections worldwide.

Figure 1. Prevalence rate of EP in different geographical regions of Egypt according to the microscopic analysis (ME), serological examination (SE), and PCR. (1. Cairo, 2. Giza, 3. Qalubia, 4. Menofia, 5. Fayom, 6. Alexandria, 7. Assiut, 8. Kafr Elsheikh, and 9. Bani Suif).

Table 21.

The prevalence of EP in different governorates of Egypt using different diagnostic methods.

| Host | Method | Year | Governorates | Sample Size | Parasite | Prevalence | Reference |

|---|

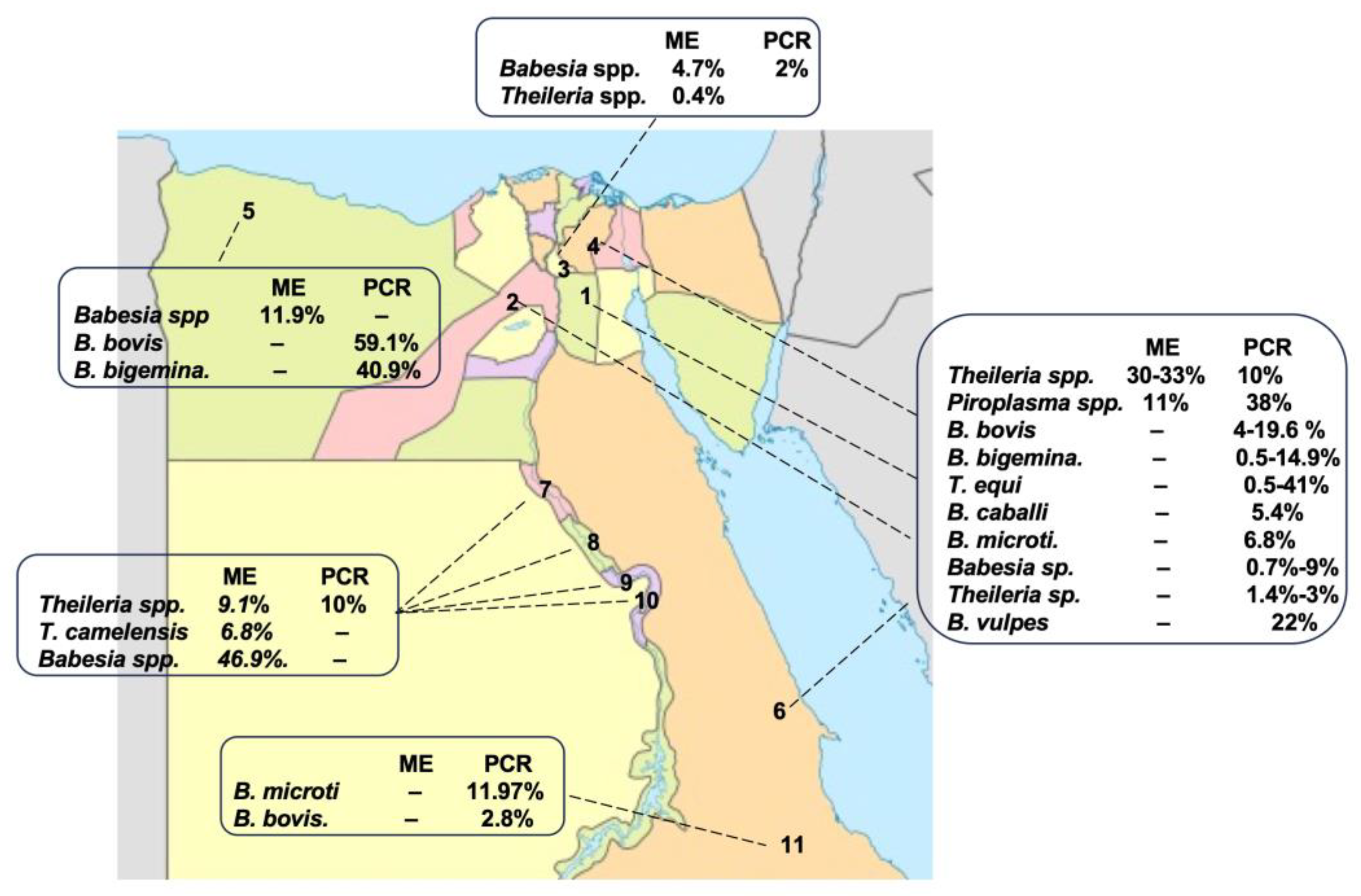

Figure 2. Prevalence rates of CP in different geographical regions of Egypt according to the ME, serological examination (SE), and PCR. 1. Cairo, 2. Giza, 3. Qalubia, 4. Sharkia, 5. Matruh, 6. Red sea, 7. Assiut, 8. Suhag, 9. Qena, 10. Luxur, and 11. Halayb w Shalaten.

Table 32.

The prevalence of CP in different regions of Egypt determined using microscopical and molecular techniques.

| Method | Year | Governorates | Sample Size | Parasite | Prevalence | Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horses | ME | |||||||||||||

| ME | 1992 | 2003 | Different localities | 18 | B. equi | 38.9% | [ | Cairo and Giza | 200 | Theileria spp. | 30% | [63][45] | 53][33] | |

| IFA | 50% | |||||||||||||

| ME | 1998 | Cairo | 74 | Theileria spp. | 33.3% | [62][44 | PCR | 77.8% | ||||||

| ] | ||||||||||||||

| ME | 2011 | Upper Egypt | 224 | T. camelensis | 6.8% | [61][43] | Horses | ME | 2011 | Not detected | 100 | T. equi | 18% | [54] |

| ME | 2014 | [ | Assiut Upper Egypt |

89 | 35 | ] | ||||||||

| Babesia | spp. | 46.9% | [ | 60 | ] | [42] | Horses | ME | 2013 | Giza | 149 | T. equi | 41.6% (Males 36.2% females 5.4%) | [58][40] |

| Theileria spp. | 9.1% | Horses | ELISA | 2015 | Cairo and Giza | 50 | ||||||||

| ME | 2015 | Giza | 243 | Theileria spp. | T. equi | 22% 30% |

30.9% | [64][46][56][38] | ||||||

| Donkeys | 50 | |||||||||||||

| PCR | 10% | Horses | ME | 2016 | Cairo and Giza | 139 | Babesia spp. | 11.4% | [45 | |||||

| ME | 2016 | ] | [ | 34 | ] | |||||||||

| Northern West Coastal zone | 331 | Babesia | spp. | 11.9% | [ | 10][13] | Donkeys | 17.8% | ||||||

| PCR | B.bovis | 59.1% | Horses | IFA | 88 | |||||||||

| B. bigemina | 40.9% | T. equi | 23.9% | |||||||||||

| Donkeys | 51 | 31.4% | ||||||||||||

| ME | 2018 | Qalubia | 700 | Babesia spp. Theileria spp. |

4.7% 0.4% |

[65][47] | Horses | cELISA | 88 | T. equi | 14.8% | |||

| PCR | 100 (negative ME) | Babesia spp | 2% | Donkeys | 51 | 23.5% | ||||||||

| nPCR | 2021 | Halayeb and Shalaten | 142 | B. bovis | 2.81% | [18][16] | Horses | ME | 2016 | Cairo and Giza | 168 | |||

| ME | 2023 | T. equi | 27.4% | [ | 45 | Cairo, Giza, Qalubya, Sharika Suhag, and Red Sea | 531 | Piroplasma spp. | 11% | [16,17][21][26] | ][34] | |||

| Donkeys | ||||||||||||||

| cPCR | 133 | 24.8% | ||||||||||||

| Babesia/Theileria | spp. | Horses | nPCR | 168 | T. equi | 61.9% | ||||||||

| Donkeys | 133 | 50.4% | ||||||||||||

| Horses | cELISA | 168 | T. equi | 15.5% | ||||||||||

| 38% | Donkeys | 133 | 25.6% | |||||||||||

| Horse | iELISA | 168 | T. equi | 17.9% | ||||||||||

| Donkeys | 133 | 53.4% | ||||||||||||

| Horses | ME | 2018 | Cairo and Giza | 141 | T. equi | 5.56% | [57][39] | |||||||

| Donkeys | ||||||||||||||

| 250 | ||||||||||||||

| Mules | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Horses Donkeys Mules |

PCR | 45 | T. equi | 30% | ||||||||||

| 50 | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Horses | cELISA | 2020 | Giza, Qalubia, Kafr, Elshiekh, and Menofia |

370 | T. equi, | 39%, | [32][22] | |||||||

| B. caballi | 11% | |||||||||||||

| Donkeys | 150 | T. equi, | 30.6% | |||||||||||

| B. caballi, | 42% | |||||||||||||

| Horses | mPCR | 2021 | Alexandria, Monufia, Ismailia, Giza, Faiyum, Beni Suef, and Cairo. |

79 | T. equi | 20.3% | [7][37] | |||||||

| B. caballi | 1.2% | |||||||||||||

| Mixed | 2.5% | |||||||||||||

| Donkeys | 76 | T. equi | 13.1% | |||||||||||

| B. caballi | 0 | |||||||||||||

| Mixed | 1.% | |||||||||||||

| Horse | cPCR | 79 | T. haneyi | 53.1% | ||||||||||

| Donkeys | 76 | T. haneyi | 38.1% | |||||||||||

| Horses | cPCR | 2022 | AL-Faiyum, AL-Giza, Beni-Suef, Al-Menufia, Al-Beheira, and Matruh | 8 | Piroplasma spp. | 0 | [59][41] |

3.2. Camel

Camel piroplasmosis has been reported in different regions of Egypt, Cairo: Giza, and Assiut—upper Egypt; Qalubia-Halayeb and Shalaten—Northern West Coastal zone; Qena and Luxor—Sharika Suhag and the Red Sea (Figure 2). First, the detection of CP was mainly dependent on ME [60[42][43][44][45],61,62,63], which reported the infection of camels with Theileria spp., T. camelensis, and Babesia spp. with different infection rates, such as Theileria spp. (9.1–33%), T. camelensis (6.8%), and Babesia spp. (46.9%). After that, a combination of ME and a molecular method (PCR) was used to obtain more accurate detection results [10,17,64,65][13][26][46][47]. Combined microscopical and molecular results have shown that CP is caused by Theileria spp., T. camelensis, B. bovis, B. bigemina, T. annulate, T. ovis, T. equi, B. caballi, B. vulpes, Babesia sp. Theileria sp., and B. microti, and it is widespread in several governorates of Egypt [9,10,17,18,20,40][13][14][16][26][30][48] (Table 32 and Figure 2). It was found that camel can be infected with different Piroplasma spp, suggesting infestations by different competent vectors. Overall, these data together suggest that camels should be screened for other species of Babesia and Theileria spp. that were not detected before via PCR using specific primer sets, followed by sequencing, in order to confirm the results.| mPCR | ||||||

| T. equi | ||||||

| (SI) | ||||||

| 41% | ||||||

| T. equi | ||||||

| (Mixed) | ||||||

| 0.5% | ||||||

| B. caballi | ||||||

| (Mixed) | ||||||

| 5.4% | ||||||

| B. bovis (SI) | 4% | |||||

| B. bovis (Mixed) | 5% | |||||

| B. bigemmina (Mixed) | 0.5% | |||||

| nPCR | B. vulpes | 22% | ||||

| Babesia sp. | 9% | |||||

| Theileria sp. | 3% | |||||

| nPCR | 2021 | Halayb and Shalaten | 142 | B. microti | 11.97% | [9][30] |

| PCR | 2022 | Giza, Asyut, Sohag, Qena, Luxor, and the Red Sea | 148 | B. bovis | 19.6% | [20][14] |

| B. bigemina | 14.9% | |||||

| Babesia sp. | 0.7% | |||||

| Theileria sp. | 1.4% | |||||

| T. equi | 0.7% | |||||

| nPCR | 2023 | Cairo and Giza | 133 | B. microti | 6.8% | [40][48] |

SI: single infection.

References

- El-Alfy, E.-S.; Abbas, I.; Baghdadi, H.B.; El-Sayed, S.A.E.-S.; Ji, S.; Rizk, M.A. Molecular Epidemiology and Species Diversity of Tick-Borne Pathogens of Animals in Egypt: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 912.

- FAOSTAT. Available online: http://www.Fao.Org/Faostat/En/#data/QA (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- State Information Service A Gateway to Egypt Horse Breeding in Egypt. Available online: https://beta.sis.gov.eg/en/egypt/culture/literature-and-heritage/horse-breeding-in-egypt/ (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Valette, D. Invisible Workers. The Economic Contributions of Working Donkeys, Horses and Mules to Livelihoods; The Brooke: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–23.

- Mahmoud, M.S.; Kandil, O.M.; Abu, N.T.; Ezz, E.; Hendawy, S.H.M.; Elsawy, B.S.M.; Knowles, D.P.; Bastos, R.G.; Kappmeyer, L.S.; Laughery, J.M.; et al. Identification and Antigenicity of the Babesia caballi Spherical Body Protein 4 (SBP4). Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 369.

- Mohamed, W.M.A.; Ali, A.O.; Mahmoud, H.Y.A.H.; Omar, M.A.; Chatanga, E.; Salim, B.; Naguib, D.; Anders, J.L.; Nonaka, N.; Moustafa, M.A.M.; et al. Exploring Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Microbiomes Helps in Detecting Tick-borne Infectious Agents in the Blood of Camels. Pathogens 2021, 10, 351.

- Burger, P.A.; Ciani, E.; Faye, B. Old World Camels in a Modern World—A Balancing Act between Conservation and Genetic Improvement. Anim. Genet. 2019, 50, 598–612.

- Chuluunbat, B.; Charruau, P.; Silbermayr, K.; Khorloojav, T.; Burger, P.A. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Mongolian Domestic Bactrian Camels (Camelus bactrianus). Anim. Genet. 2014, 45, 550–558.

- Ramadan, S.; Inoue-Murayama, M. Advances in Camel Genomics and Their Applications: A Review. J. Anim. Genet. 2017, 45, 49–58.

- Kamani, J.; Turaki, U.; Egwu, G.; Aliyu, M.; Mani, A.; Kida, S.; Gimba, A.; Adam, K. Haemoparasites of camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Maidu-guri, Nigeria. Anim. Res. Int. 2008, 2, 838–839.

- Mahmoud, M.; Wassif, I.; El-Sayed, A.; Noaman, E.A. Some epidemiological studies on camel mycoplasmosis in Egypt. J. Egypt. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2019, 79, 699–709.

- Sallam, A.M. Future opportunities for genetic improvement of the Egyptian camels. Egypt. J. Anim. Prod. 2020, 57, 39–45.

- Abou El Naga, R.T.; Barghash, M.S. Blood Parasites in Camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Northern West Coast of Egypt. J. Bacteriol. Parasitol. 2016, 7, 1.

- Salman, D.; Sivakumar, T.; Otgonsuren, D.; Mahmoud, M.E.; Elmahallawy, E.K.; Khalphallah, A.; Kounour, A.M.E.Y.; Bayomi, S.A.; Igarashi, M.; Yokoyama, N. Molecular Survey of Babesia, Theileria, Trypanosoma, and Anaplasma Infections in Camels (Camelus dromedaries) in Egypt. Parasitol. Int. 2022, 90, 102618.

- Kizzi Asala. Available online: https://www.Africanews.com/2020/09/16/Camel-Racing-Back-on-in-Egypt-Post-Covid-19-Lockdown-Hiatus// (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- El-Sayed, S.A.E.S.; El-Adl, M.A.; Ali, M.O.; Al-Araby, M.; Omar, M.A.; El-Beskawy, M.; Sorour, S.S.; Rizk, M.A.; Elgioushy, M. Molecular Detection and Identification of Babesia bovis and Trypanosoma spp. In One-Humped Camel (Camelus dromedarius) Breeds in Egypt. Vet. World 2021, 14, 625–633.

- Napp, S.; Chevalier, V.; Busquets, N.; Calistri, P.; Casal, J.; Attia, M.; Elbassal, R.; Hosni, H.; Farrag, H.; Hassan, N.; et al. Understanding the Legal Trade of Cattle and Camels and the Derived Risk of Rift Valley Fever Introduction into and Transmission within Egypt. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006143.

- Church, S. BEASTS of Burden Targeting Disease in Africa’s Working Donkeys and Horses. Available online: https://thehorse.com/features/beasts-of-burden-africas-working-horses-and-donkeys/ (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Knowles, D.P.; Kappmeyer, L.S.; Haney, D.; Herndon, D.R.; Fry, L.M.; Munro, J.B.; Sears, K.; Ueti, M.W.; Wise, L.N.; Silva, M.; et al. Discovery of a novel species, Theileria haneyi n. sp. infective to equids, highlights exceptional genomic diversity within the genus Theileria: Implications for apicomplexan parasite surveillance. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018, 48, 679–690.

- Romero-Salas, D.; Solis-Cortés, M.; Zazueta-Islas, H.M.; Flores-Vásquez, F.; Cruz-Romero, A.; Aguilar-Domínguez, M.; Salguero-Romero, J.L.; de León, A.P.; Fernández-Figueroa, E.A.; Lammoglia-Villagómez, M.Á.; et al. Molecular Detection of Theileria equi in Horses from Veracruz, Mexi-co. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021, 12, 101671.

- Elsawy, B.S.M. Advanced Studies on Camel and Equine Piroplasma in Egypt. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt, 2022.

- Selim, A.; Khater, H. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Equine Piroplasmosis in North Egypt. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, 101549.

- Rüegg, S.R.; Heinzmann, D.; Barbour, A.D.; Torgerson, P.R. Estimation of the Transmission Dynamics of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi in Horses. Parasitology 2008, 135, 555–565.

- Sears, K.; Knowles, D.; Dinkel, K.; Mshelia, P.W.; Onzere, C.; Silva, M.; Fry, L. Imidocarb Dipropionate Lacks Efficacy against Theileria haneyi and Fails to Consistently Clear Theileria equi in Horses Co-Infected with T. haneyi. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1035.

- Sears, K.P.; Knowles, D.P.; Fry, L.M. Clinical Progression of Theileria haneyi in Splenectomized Horses Reveals Decreased Virulence Compared to Theileria equi. Pathogens 2022, 11, 254.

- Mahdy, O.A.; Nassar, A.M.; Elsawy, B.S.M.; Alzan, H.F.; Kandil, O.M.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Suarez, C.E. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Piroplasma Species-Infecting Camel (Camelus dromedaries) in Egypt Using a Multipronged Molecular Diagnostic Approach. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1178511.

- Faraj, A.A.; Hade, B.F.; Amery, A.M.A. Conventional and Molecular Study of Babesia Spp. of Natural Infection in Dragging Horses at Some Areas of Bagdad City, IRAQ. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 50, 909–915.

- Qablan, M.A.; Sloboda, M.; Jirků, M.; Oborník, M.; Dwairi, S.; Amr, Z.S.; Hořín, P.; Lukeš, J.; Modrý, D. Quest for the Piroplasms in Camels: Identification of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi in Jordanian Dromedaries by PCR. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 186, 456–460.

- Vannier, E.; Gewurz, B.E.; Krause, P.J. Human Babesiosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 22, 469–488.

- Abdo -Rizk, M.; El-Adl, M.A.; Al-Araby, M.; Ali, M.O.; Abd El-Salam El-Sayed, S.; El-Beskawy, M.; Gomaa, N.A. Molecular Detection of Babesia Microti in One-Humped Camel (Camelus dromedarius) in Halayeb and Shalateen, Halayeb, Egypt. Egypt. Vet. Med. Soc. Para-Sitology J. (EVMSPJ) 2021, 17, 109–119.

- Arafa, M.I. Studies on the Ecto and Endoparasites of Equines in Assiut Governorate. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt, 1998.

- Mahmoud, M.S.; El-ezz, N.T.A.; Abdel-shafy, S.; Nassar, S.A.; El Namaky, A.H.; Khalil, W.K.B.; Knowles, D.; Kappmeyer, L.; Silva, M.G.; Suarez, C.E.; et al. Assessment of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi Infections in Equine Populations in Egypt by Molecular, Serological and Hematological Approaches. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 260.

- Farah, A.W.; Hegazy, N.A.M.; Romany, M.M.; Soliman, Y.A.; Daoud, A.M. Molecular Detection of Babesia Equi in Infected and Carrier Horses by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2003, 10, 73–79.

- Mahdy, O.A.; Nassar, A.S.; Mohamed, B.S.; Mahmoud, M.S. Comparative Diagnosis Utilizing Molecular and Serological Techniques of Theileria equi in Distinct Equine Population in Egypt. Int. J. Chemtech Res. 2016, 9, 185–197.

- Ibrahim, A.K.; Gamil, I.S.; Abd-El Baky, A.A.; Hussein, M.M.; Tohamy, A.A. Comparative Molecular and Conventional Detection Methods of Babesia equi (B. equi) in Egyptian Equine. Glob. Vet. 2011, 7, 201–210.

- Bhoora, R.; Quan, M.; Matjila, P.T.; Zweygarth, E.; Guthrie, A.J.; Collins, N.E. Sequence Heterogeneity in the Equi Merozoite Antigen Gene (Ema-1) of Theileria equi and Development of an Ema -1-Specific TaqMan MGB TM Assay for the Detection of T. equi. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 172, 33–45.

- Elsawy, B.S.M.; Nassar, A.M.; Alzan, H.F.; Bhoora, R.V.; Ozubek, S.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Kandil, O.M.; Mahdy, O.A. Rapid Detection of Equine Piroplasms Using Multiplex PCR and First Genetic Characterization of Theileria haneyi in Egypt. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1414.

- Mahmoud, S.; Mahmoud, M.S.; El-Hakim, A.E.; Hendawy, S.H.; Shalaby, H.A.; Kandil, O.M.; Abu El-Ezz, N.M. Diagnosis of Theilria equi Infections in Equines Using Immunoaffinity Purified Antigen. Glob. Vet. 2015, 15, 192–201.

- El-seify, M.A.; City, K.E.; Helmy, N.; Mahmoud, A.; Soliman, M. Use Molecular Techniques as an Alternative Tool for Diagnosis and Characterization of Theileria equi. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 32, 5–11.

- Salib, F.A.; Youssef, R.R.; Rizk, L.G.; Said, S.F. Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Therapy of Theileria equi Infection in Giza, Egypt. Vet. World 2013, 6, 76–82.

- Abdel-Shafy, S.; Abdullah, H.H.A.M.; Elbayoumy, M.K.; Elsawy, B.S.M.; Hassan, M.R.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Hegazi, A.G.; Abdel-Rahman, E.H. Molecular Epidemiological Investigation of Piroplasms and Anaplasmataceae Bacteria in Egyptian Domestic Animals and Associated Ticks. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1194.

- Abd El Maleck, B.; Abed, G.; Mandour, A. Some Protozoan Parasites Infecting Blood of Camels (Camelus dromedarius) at Assiut Locality, Upper Egypt. J. Bacteriol. Parasitol. 2014, 5, 2.

- Hamed, M.; Zaitoun, A.; El-Allawy, T.; Mourad, M. Investigation of Theileria camelensis in Camels Infested by Hyalomma dromedarii Ticks in Upper Egypt. J. Adv. Vet. Res. 2011, 1, 4–7.

- El-Refaii, M.A.; Wahba, A.; Gehan, J.S. Studies on Theileria Infection among Slaughtered Camels in Egypt. Egypt. J. Med. Sci. 1998, 19, 1–17.

- Nassar, A.M. Theileria Infection in Camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Egypt. Vet. Parasitol. 1992, 43, 147–149.

- Youssef, S.Y.; Yasien, S. Vector Identification and Clinical, Hematological, Biochemical, and Parasitological Characteristics of Camel (Camelus dromedarius) Theileriosis in Egypt. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2015, 47, 649–656.

- Abdel Gawad, S.M. Recent Diagnosis of Protozoa Affecting Camels. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Benha University, Benha, Egypt, 2018.

- Ashour, R.; Hamza, D.; Kadry, M.; Sabry, M.A. Molecular Detection of Babesia microti in Dromedary Camels in Egypt. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 91.

More