You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Fawad Javed.

Orthognathic surgery (OS) is usually performed to improve functional and esthetic parameters by repositioning the maxilla, mandible and/or the symphysis, particularly among patients that have either passed the pubertal growth spurt or may be unsuitable for orthodontic camouflage.

- clear aligner therapy

- clear aligners

- complications

- edema

- facial swelling

1. Introduction

Orthognathic surgery (OS) is usually performed to improve functional and esthetic parameters by repositioning the maxilla, mandible and/or the symphysis, particularly among patients that have either passed the pubertal growth spurt or may be unsuitable for orthodontic camouflage [1]. Surgical interventions such as LeFort and sagittal split osteotomies are often performed in conjunction to orthodontic tooth movement (OTM), particularly in patients with severe craniofacial deformities to produce a functional and stable occlusal outcome [2,3][2][3]. Following OS, orthodontic therapy (OT) using fixed appliances is conventionally performed to attain the desired tooth movement [4,5][4][5]. Clear aligner therapy (CAT) emerged as a potential therapeutic approach to induce OTM and treat dental malocclusions over two decades ago. These are removable appliances that can produce clinically acceptable orthodontic outcomes (OO) that are comparable to clinically satisfactory outcomes achieved using fixed OT [6,7][6][7]. With advancements in clinical orthodontics and related research, CAT has been shown to be an effective approach for the correction of not only mild to moderate but severe malocclusions [8], and it can also be used successfully after OS to attain OTM [9,10,11,12,13][9][10][11][12][13]. However, according to Robitaille et al. [13] esthetic outcomes in terms of occlusion are superior with fixed OT in contrast to CAT after OS. Papageorgiou et al. [14] also concluded that OT in adults using CAT is associated with worse esthetic outcomes in contrast to OT performed using fixed appliances.

Postoperative facial swelling (FS) after OS is a common yet significant concern as it can cause discomfort, hinder oral intake, affect speech and prolong the recovery period [9,10,11,12,13][9][10][11][12][13]. However, there is a paucity of research specifically comparing the impact of CAT and fixed OT on postoperative FS following OS. Guktaka et al. [10] used three-dimensional (3D) subtraction imaging to compare the volume of FS after OS in patients undergoing CAT (n = 11 patients) and fixed OT (n = 11 patients). In thisa study [10], OS interventions comprised LeFort-1 osteotomy (L1O), genioplasty and bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO). The results showed that patients undergoing CAT displayed a significantly smaller volume of FS compared with individuals undergoing fixed OT at a one-week follow-up [10]. The authors concluded that in the short term (up to the first post-operative week), FS is less in patients undergoing CAT than those undergoing fixed OT [10]. On the other hand, in a retrospective chart review and 3D morphometric study, Kankam et al. [12] showed no significant difference in FS among patients that either underwent CAT or fixed OT 6 months after OS. The authors suggested CAT can be used as an alternative to fixed OT after OS [12]. It is, however, pertinent to mention that the studies by Guktaka et al. [10] and Kankam et al. [12] were based on the supposition that peri-operative OT with CAT causes less post-operative FS than fixed OT; however, a scientific justification in this regard remained unclarified in these studies [10,12][10][12].

2. General Characteristics of Included Studies

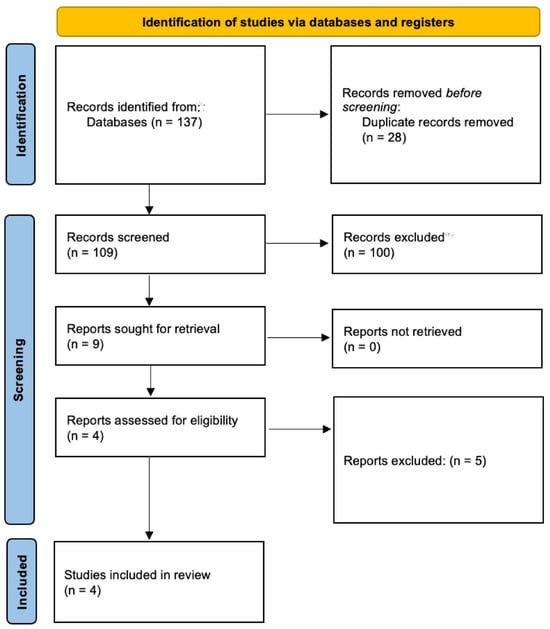

The initial search yielded 137 studies. After removal of duplicates, full texts of 109 studies were retrieved and assessed with reference to the FQ and EC. Four retrospective studies [10,11,12,13][10][11][12][13] addressed the FQ and fulfilled the EC. In these studies [10[10][11][12][13],11,12,13], the number of participants and their ages ranged between 22 and 29 and ~16 and 55.1 years, respectively. In the CAT and fixed OT groups, the number of males ranged between 46–64% and 24–64%, respectively [10,11,12,13][10][11][12][13]. Two studies [10,12][10][12] assessed the BMI of patients in the CAT and fixed OT groups. In the study by Kankam et al. [12], the BMI of patients in the CAT and fixed OT groups was 24.18 ± 3.79 and 23.49 ± 5.11 Kg/m2, respectively. The BMI of patients in the CAT and fixed OT groups was 20.9 ±2.4 and 25 ± 6.4 Kg/m2, respectively, in the study by Guntaka et al. [10]. In the study by Robitaille et al. [13] 37.5%, 50% and 12.5% individuals had skeletal class-II, skeletal class-III and anterior open bite, respectively, in the CAT group. In thisa study [13], 52%, 32%, 12% and 4% patients in the fixed OT group had skeletal class-II, skeletal class-III, anterior open bite and skeletal class-I with asymmetry, correspondingly. Data pertaining to baseline dental malocclusion were not reported in all studies (Table 1 and Figure 1) [10,11,12,13][10][11][12][13].

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1. General characteristics of retrospective studies included.

| Authors et al. | Patients (n) | CAT Group (n) and Gender (%) | Fixed OT Group (n) and Gender (%) | Age in Years (CAT Group) | Age in Years (Fixed OT Group) | BMI (CAT Group) | BMI (Fixed OT Group) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guntaka et al. [10] | 22 | 11 Male: 64% Female: 36% |

11 Male: 64% Female: 36% |

20.5 ± 3.8 years | 20.9 ± 2.4 years | 23.8 ± 3.6 kg/m2 | 25 ± 6.4 kg/m2 |

| Liou et al. [11] | 33 | 19 Male: 47% Female: 53% |

14 Male: 79% Female: 21% |

20 (19–27) years | 21 (19–24) years | NR | NR |

| Kankam et al. [12] | 33 | 13 Male: 46.2% Female: 53.8% |

20 Male: 50% Female: 50% |

20.81 ± 4.1 years | 19.46 ± 3.32 years | 24.18 ± 3.79 kg/m2 | 23.49 ± 5.11 kg/m2 |

| Robitaille et al. [13] | 49 | 24 Male: 46% Female: 54% |

25 Male: 24% Female: 76% |

30.7 years (18.8–55.1 years) |

24.9 years (16.7–40.6 years) |

NR | NR |

3. Orthognathic Surgery-Related Parameters

In the study by Kankam et al. [12] all patients underwent BSSO and LeFort-1 osteotomy, whereas BSSO alone was performed in 50% and 36% patients in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively, in the study by Robitaille et al. [13] In this study [13], LeFort-1 osteotomy alone was performed in 37.5% and 8% individuals in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively. Nine% and 9% underwent BSSO alone in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively, in the study by Guntaka et al. [10], whereas 55% and 55% patients in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively, underwent LeFort-1 osteotomy alone [10]. In this study, 18% and 18% underwent LeFort-1 osteotomy with BSSO and genioplasty in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively [10]. In the study by Liou et al. [11] LeFort-1 osteotomy with BSSO and genioplasty was performed in 78.9% and 71.4% individuals in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively. In this study [11], LeFort-1 osteotomy with BSSO was performed in 21.1% and 28.6% of individuals in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively. Duration of follow-up was reported in studies by Guntaka et al. [10] and Kankam et al. [12], which was up to 7 weeks and 6 months, correspondingly (Table 2).

Table 2.

Orthognathic surgery-related parameters.

| Authors et al. | Orthodontic Therapy | Type of Orthognathic Intervention (Percentage of Patients) | Operating Time | Duration of Hospital Stay | Post-Operative Follow-Up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSSO or LeFort-1 Osteotomy | BSSO Alone | LeFort-1 Osteotomy Alone | BSSO + LeFort-1 Osteotomy | LeFort-1 Osteotomy + Genioplasty | LeFort-1 ± BSSO + Genioplasty | |||||

| Guntaka et al. [10] | CAT | 63.6% | 9% | 55% | 9% | 9% | 18% | 180.5 ± 71.7 min | NR | Up to 7 weeks |

| Fixed OT | 63.6% | 9% | 55% | 9% | 9% | 18% | 167.4 ± 44.1 min | NR | ||

| Liou et al. [11] | CAT | NA | NA | NA | 21.1% | NA | 78.9% | NR | NR | NR |

| Fixed OT | NA | NA | NA | 28.6% | NA | 71.4% | NR | NR | ||

| Kankam et al. [12] | CAT | NA | NA | NA | 100% | NA | NA | 303.9 ± 64.5 min | 1.77 ± 0.6 days | 6 months |

| Fixed OT | NA | NA | NA | 100% | NA | NA | 287.3 ± 58.9 min | 2.2 ± 1.1 days | ||

| Robitaille et al. [13] | CAT | NA | 50% | 37.5% | 12.5% * | NA | NA | NR | NR | NR |

| Fixed OT | NA | 36% | 8% | 56% * | NA | NA | NR | NR | ||

4. Main Study Outcomes

Two [10,12][10][12] and two [11,13][11][13] studies assessed FS and postoperative occlusion among patients who received CAT and fixed OT, respectively.4.1. Postoperative Occlusion

In the study by Liou et al. [11] postoperative occlusion was comparable among patients that underwent CAT or fixed OT after OS. Liou et al. [11] assessed occlusal outcome using %reduction in the PAR index score, which had no significant difference between both the CAT and fixed OT groups (p = 0.142). Robitaille et al. [13] assessed occlusal outcome using the American Board of Orthodontics Objective Grading System. Results by Robitaille et al. [13] demonstrated that postoperative occlusion was better in patients that underwent fixed OT compared to CAT after OS.4.2. Facial Swelling

One study [12] reported that there is no difference in postoperative FS among patients that undergo CAT or FS after OS. In the study by Guntaka et al. [10] patients treated with CAT demonstrated less FS in the first post-surgical week compared with individuals that underwent fixed OT. In this study [10], postoperative FS was comparable in both groups at seven-weeks’ follow-up. Both studies [10,12][10][12] used 3D images to compare FS. The study by Guntaka et al. [10] measured between the middle and lower third of the face, excluding the nose. The study by Kankam et al. [12] measured between the middle and lower face.4.3. Duration of Orthognathic Surgery

Two studies [10,12][10][12] reported the duration (in minutes) of OS. In the study by Kankam et al. [12] there was no significant difference in the duration of OS in patients that underwent CAT (303.9 ± 64.5 min) and fixed OT (287.3 ± 58.9 min). In the study by Guntaka et al. [10] the duration of OS was 180.5 ± 71.7 and 167.4 ± 44.1 min for patients in the CAT and fixed OT groups, respectively.4.4. Hospitalization Rates

In one study [12], patients in the CAT and fixed OT were hospitalized post-operatively for 1.77 ± 0.6 and 2.2 ± 1.1 days, respectively.4.5. Risk of Bias Assessment, Sample Size Estimation and GRADE Analysis

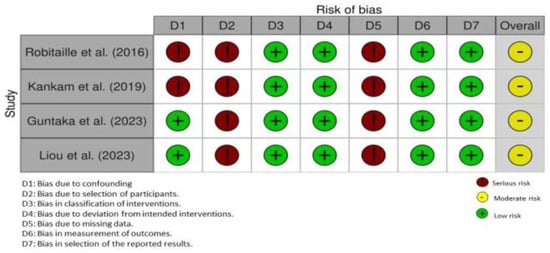

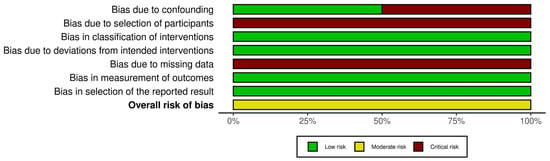

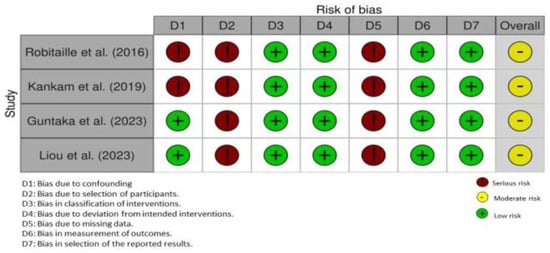

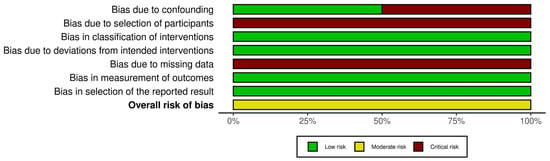

All studies [10,11,12,13][10][11][12][13] had a moderate RoB (Figure 2 and Figure 3). A prior sample size estimation was performed in none of the studies [10,11,12,13][10][11][12][13]. The quality of available evidence regarding the difference in postoperative FS and occlusion attained with CAT and fixed OT was very low.

Figure 3. Risk of bias assessment of each study using the weighted bar plot.

References

- Huang, C.S.; Hsu, S.S.; Chen, Y.R. Systematic review of the surgery-first approach in orthognathic surgery. Biomed. J. 2014, 37, 184–190.

- Yuan, H.; Zhu, X.; Lu, J.; Dai, J.; Fang, B.; Shen, S.G. Accelerated orthodontic tooth movement following le fort I osteotomy in a rodent model. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 764–772.

- Chen, C.M.; Hsu, H.J.; Liang, S.W.; Chen, P.H.; Hsu, K.J.; Tseng, Y.C. Two-thirds anteroposterior ramus length is the preferred osteotomy point for intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2022, 26, 1229–1239.

- Hohoff, A.; Joos, U.; Meyer, U.; Ehmer, U.; Stamm, T. The spectrum of Apert syndrome: Phenotype, particularities in orthodontic treatment, and characteristics of orthognathic surgery. Head Face Med. 2007, 3, 10.

- Breuning, K.H.; van Strijen, P.J.; Prahl-Andersen, B.; Tuinzing, D.B. Duration of orthodontic treatment and mandibular lengthening by means of distraction or bilateral sagittal split osteotomy in patients with Angle Class II malocclusions. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2005, 127, 25–29.

- Robertson, L.; Kaur, H.; Fagundes, N.C.F.; Romanyk, D.; Major, P.; Flores Mir, C. Effectiveness of clear aligner therapy for orthodontic treatment: A systematic review. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 23, 133–142.

- Ke, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, M. A comparison of treatment effectiveness between clear aligner and fixed appliance therapies. BMC Oral. Health 2019, 19, 24.

- Jaber, S.T.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Burhan, A.S. The Effectiveness of In-house Clear Aligners and Traditional Fixed Appliances in Achieving Good Occlusion in Complex Orthodontic Cases: A Randomized Control Clinical Trial. Cureus 2022, 14, e30147.

- Kankam, H.K.N.; Gupta, H.; Sawh-Martinez, R.; Steinbacher, D.M. Segmental Multiple-Jaw Surgery without Orthodontia: Clear Aligners Alone. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 142, 181–184.

- Guntaka, P.K.; Kiang, K.; Caprio, R.; Parry, G.J.; Padwa, B.L.; Resnick, C.M. Do patients treated with Invisalign have less swelling after orthognathic surgery than those with fixed orthodontic appliances? Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 2023, 163, 243–251.

- Liou, Y.J.; Chen, P.R.; Tsai, T.Y.; Lin, S.; Chou, P.Y.; Lo, C.M.; Chen, Y.R. Comparative assessment of orthodontic and aesthetic outcomes after orthognathic surgery with clear aligner or fixed appliance therapy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023.

- Kankam, H.; Madari, S.; Sawh-Martinez, R.; Bruckman, K.C.; Steinbacher, D.M. Comparing Outcomes in Orthognathic Surgery Using Clear Aligners Versus Conventional Fixed Appliances. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 1488–1491.

- Robitaille, P. Duration and Outcomes of Combined Orthodontic-Surgical Treatment with Invisalign®. 2016. Available online: https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/handle/1866/16432 (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Papageorgiou, S.N.; Koletsi, D.; Iliadi, A.; Peltomaki, T.; Eliades, T. Treatment outcome with orthodontic aligners and fixed appliances: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Eur. J. Orthod. 2020, 42, 331–343.

More