Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lindsay Dong and Version 1 by Giuseppe De Rosa.

Global warming (GW) is a current challenge for livestock systems, including water buffalo farms. Buffaloes have anatomical traits such as thick skin and a high density of capillaries and arterioles to improve sensitive heat losses. However, they are exposed to high temperatures and tropical and humid climates that make them susceptible to heat stress.

- water buffalo

- global warming

1. Introduction

Global warming (GW) refers to the increase in the global temperature since 1880, where the worldwide temperature has increased by an average of 1 °C [1]. Projections to 2080 calculate an expected increase of 3.5–5.5 °C [2]. When addressing GW and livestock species, heat stress is the most important outcome that negatively impacts animals’ health, welfare, and productive performance [3]. Apart from the health issues that it represents to animals, heat stress has serious economic implications by increasing the morbidity and mortality of farm animals and decreasing their feed intake, feed conversion ratio, fertility, and conception rate, as well as causing low milk yields [4,5][4][5]. For example, losses of around 63.9% (USD 1.5 billion per year and up to USD 2.26 billion) in the dairy industry of the United States have been associated with heat stress, while financial losses of 60% (up to USD 39.94 billion/year) have been estimated in tropical climates [2,6,7][2][6][7].

Water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) are known to be heat-tolerant and well-adapted species to humid and tropical climates [10][8]. However, countries like India, Pakistan, and China—where buffalo farming is prevalent—have reported increases of approximately 0.7 °C, 1.6 °C, and 1.7 °C, respectively, in the past 32 years [11,12,13][9][10][11]. According to different authors, water buffaloes’ thermoneutral zone is considered to be between 13.0 °C and 24 °C, with a relative humidity between 55 and 60% [14,15,16][12][13][14]. When the body temperature of buffaloes exceeds its normal values—ranging from 37.5 °C to 39 °C—a cascade of physiological and behavioral responses are triggered to restore thermoneutrality and prevent heat stress consequences, including health and productive outcomes [17,18][15][16].

Water buffaloes are predominant species in humid climates and are adapted to environmental temperatures reaching up to 46 °C [16][14]. In contrast to Bos taurus or Bos indicus cattle, buffaloes have morphological characteristics that can represent an advantage/disadvantage in certain climates. For example, high concentrations of melanin in their skin protect buffaloes. The protection provided by melanin is only associated with UVa and UVb radiation. The relationship with solar radiation (essentially short-wavelength radiation) is revealed in a greater absorbance (not necessarily a greater transmittance) and an increase in the skin temperature [16,19][14][17]. On the other hand, the skin thickness and the high density of dermal arterioles and capillaries facilitate sensible heat loss through conduction, radiation, and convection [16,17][14][15]. The reduced number of functional sweat glands and the sparsely distributed hair might make buffaloes susceptible to heat stress [20,21][18][19].

One of the main issues when livestock is exposed to chronic heat stress is the physiological alterations that have negative influences on productive performance. Some authors projected a decrease of 12.78% by 2080 in dairy Murrah buffaloes’ productivity [2]. Moreover, livestock farming can play a non-negligible role in the negative effects of GW due to its direct effect on soil degradation and deforestation attributed to foraging. Another relevant aspect is the contribution of livestock to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions due to their enteric fermentation, representing 11% of the total emissions. Therefore, promoting sustainable intensive and extensive productive systems and intensive rotational grazing (e.g., holistic systems) is essential for both humans and animals to reduce the adverse influence of farming on GW [22,23,24][20][21][22].

To prevent heat stress consequences and reductions in productive parameters, current buffalo farms have implemented alternatives to promote heat loss via evaporation such as using sprinklers, fans, and natural body waters so buffaloes can perform wallowing—a thermoregulatory species-specific behavior—as well as providing naturally or artificially shaded areas [16][14]. Furthermore, strategies to alleviate heat stress include methods to recognize thermal alterations in buffaloes, such as the use of infrared thermography (IRT) to detect changes in the surface temperature of animals in response to hyperthermia [25][23].

2. Adverse Effects of Global Warming on Livestock Farming: An Approach for Meat and Dairy Products

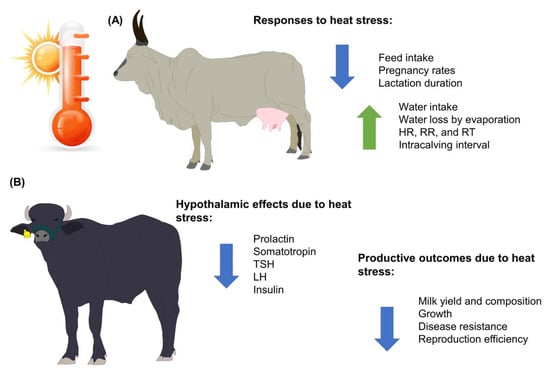

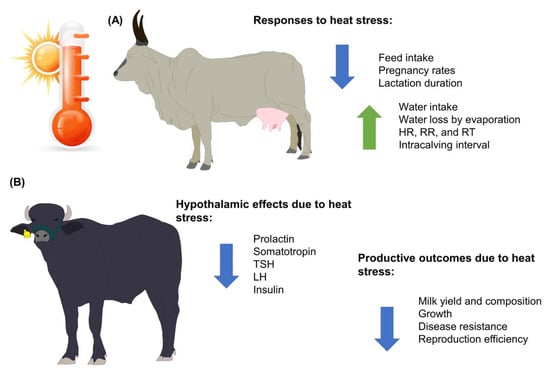

Currently, more than 8 billion people have increased the demand for meat and dairy products by approximately 40 and 50%, respectively, in the past years [26,27,28,29][24][25][26][27]. When considering the increase in demand for livestock farming, GW and its projected increases in temperature of 3.5 to 5.5 °C by 2080 represent challenges due to the effects on the productive and reproductive performance of livestock, including buffalo farms [2,27,30][2][25][28]. Buffaloes’ performance, health, and welfare are affected both directly and indirectly by the environment. Although water buffaloes are considered animals that possess morphological, anatomical, and behavioral characteristics that help them adapt to hot and humid climates, heat stress has a detrimental effect on the animals’ productive and reproductive performances. Heat stress in water buffaloes affects milk performance and animal welfare because heat stress decreases feed intake, which is closely linked to the amount of milk that is produced. However, feed intake causes metabolic heat generation, which can be detrimental when animals are already in a heat stress state (Figure 1). In addition, the intensification and confinement of water buffaloes to maintain greater control over their feeding and to achieve better milk yield and constituents have promoted the use of supplementary cooling systems such as fans and foggers to minimize the effects of heat stress on dairy buffaloes in hot weather [31][29].

Figure 1. Main effects of heat stress on water buffaloes and bovines of the genus Bos. (A) Animals from the Bos genus. (B) Animals from the Bubalus genus. HR: heart rate; LH: luteinizing hormone; RR: respiratory rate; RT: rectal temperature; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone.

To maintain adequate microclimate parameters inside buffalo farming facilities, the room temperature, relative humidity, lighting, and ventilation, among other factors, must be considered [32][30]. This is relevant because it is estimated that 10–30% of animal productivity is determined by the microclimate [33][31]. In the case of water buffaloes reared in intensive systems, facilities must promote the thermal comfort of animals by keeping room temperatures between 13.0 °C and 24 °C and keeping humidity percentages between 55 and 60% [14,15,16][12][13][14]. Therefore, adopting strategies to achieve thermoneutrality in animals is important in buffalo farming.

In this sense, foggers distribute air droplets that quickly evaporate and cool the circulating air, increasing convective heat loss under stress conditions in cattle [34][32]. Seerapu et al. [34][32] evaluated the effect of microclimate alteration on milk production and milk composition in 40 Murrah buffaloes. By comparing the use of foggers, fans, foggers plus fans, and control conditions, the authors found differences in the rectal temperature (RT) of the buffaloes. While the RT of the control group remained at 39.16 °C, the foggers plus fans group had an RT of 38.61 °C. Similarly, the respiratory rate (RR) and pulse rate decreased, observing a decrease of 15.66 breaths/min and 16.47 beats/min, respectively, in the foggers group.

Strategies are required to minimize the consequences of the effects of climate change on buffaloes’ milk yields. For example, Sigdel et al. [35][33] evaluated the effects of extreme temperatures and relative humidity on the milk yield of Murrah buffaloes. A strong negative correlation (p > 0.01) was found between the milk yield and the temperature and humidity index (THI), indicating that the milk yield decreases at the same time that the THI increases (r = −0.80).

The estimated decline in milk yield in buffaloes due to GW ranges from 10 to 30% during the first lactation and from 5 to 20% during the second and third lactations [27][25]. In addition, GW also affects the quality and quantity of available grass for foraging, and causes an increasing incidence of diseases and reduced water availability that negatively impacts dairy farms [36][34].

Regarding meat production, water buffaloes are adapted to different production systems because they can efficiently use more highly lignified pastures, with an estimate meat production of 4,290,212 tones, particularly in Asia [37][35]. Notwithstanding this, Bragaglio et al. [38][36] compared different diets and found a higher share of protein and fat in the milk of buffaloes (Mediterranean buffalo in Italy) fed with corn silage. Meat buffaloes can be housed on irregular terrain and wetlands, representing a lower environmental impact due to their use in systems that could hardly be used for agriculture or dwellings [39,40][37][38].

Grazing buffaloes in grasslands improves soil functionality by preventing desertification and using their manure without increasing methane production. Moreover, buffaloes have more efficient fiber digestion than Bos cattle, making it more suitable for them to consume tropical forages [39][37]. Although the meat quality highly depends on the buffalo breed and age at slaughter (where young male buffalo meat is considered more suitable [41][39]), Di Stasio and Brugiapaglia [37][35] mention that the great capacity of buffaloes to adapt to several rearing areas and management systems is an advantage of buffalo farming.

3. Thermoregulatory Physiology of Water Buffaloes Facing Heat Stress

3.1. Physiological Aspects

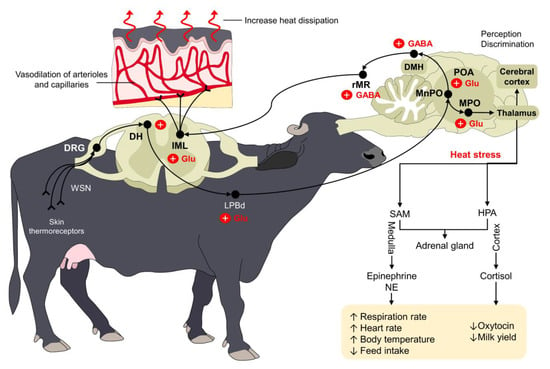

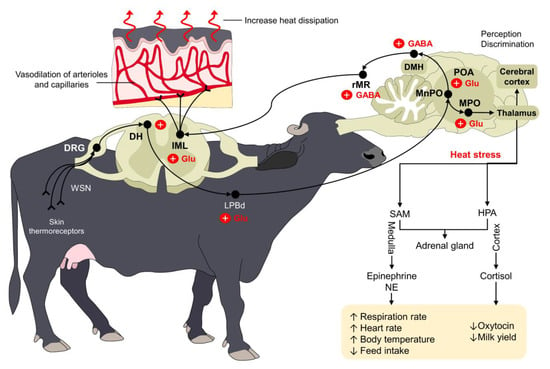

Thermoregulation aims to maintain body temperature within a certain range where cellular functionality can be preserved. Under normal circumstances, the organism uses a series of physiological, endocrine, and behavioral adaptations to promote thermoneutrality [3]. However, when animals are exposed to hot climates and develop heat stress, the central nervous system (CNS) triggers several responses to restore homeostasis [43,44][40][41]. The preoptic area (POA) of the hypothalamus, a key structure for thermoregulation, contains approximately 30–40% of warm-sensitive neurons that respond to environmental warming through peripheral thermoreceptors located in the skin [45,46][42][43]. Transient receptor potential cation channels—known as TRP—are a large family of thermosensitive receptors that can detect both heat and cold stimuli [47,48][44][45]. Five of these receptors (TRPV1-4 and TRPM2) are activated with non-noxious and noxious heat. TRPV1 and TRPV2 respond to high temperatures between 43 °C and 55 °C, respectively [47][44], and are expressed in Aδ and C fibers [49][46]. When considering that heat stress can increase the RT to 39.71 °C in water buffaloes exposed to environmental temperatures around 27–35 °C [17][15], the activation of these warm-sensitive afferent fibers is essential to initiate a cascade of responses to prevent hyperthermia. Several studies in young and adult buffaloes indicate that environmental characteristics such as the ambient temperature or the facility design affect the internal temperature of water buffalo, potentially reaching critical points. The hypothalamus can recognize such increases in the body temperature, and cutaneous thermosensitive receptors can also send excitatory signals to warm-sensitive neurons (WSNs) in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) of the spinal cord [52][47]. From the spinal cord, the signal is transmitted to the POA using the dorsal part of the lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPBd), where glutamatergic neurons participate [53][48]. Other regions of the POA, such as the medial preoptic area (MPOA) and the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO), are also involved in the physiological control against heat stress [44,46][41][43]. From these nuclei, efferent pathways leading to skin vasodilation are triggered by projections from the POA to the rostral raphe pallidus (rRPA) [44][41], while evaporative heat loss mechanisms (e.g., sweating, panting, or tachypnea) use projections from the intermediolateral column cells (IML) in the spinal cord and the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVMM) [54][49]. This neural pathway is schematized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Thermoregulatory pathway of water buffaloes when facing heat stress. Peripheral thermoreceptors process and transmit information about the external thermal environment of mammals. Through a complex connection between the spinal cord (DRG and DH), the LPBd, and supraspinal structures (primarily the POA, MPO, and MnPO), the organism triggers different responses to increase heat dissipation. For example, the vasodilation of dermal arterioles and capillaries increases heat loss in water buffaloes exposed to heat stress. Similarly, other compensatory mechanisms such as increases in respiratory rate and heart rate serve to restore thermoneutrality. DH: dorsal horn; DMH: dorsomedial hypothalamus; DRG: dorsal root ganglion; GABA: gamma amino butyric acid; GLU: glutamate; HPA: hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; IML: intermediolateral; LPBd: dorsal part of the lateral parabrachial nucleus; MnPO: median preoptic nucleus; MPO: medial preoptic area; NE: norepinephrine; POA: preoptic area; rMR: rostral medullary raphe region; SAM: sympathetic-adrenomedullary; ↑: increase; ↓: decrease.

The vasodilation of dermal blood vessels is one of the initial resources that animals use to lose heat [21][19]. A way to assess the amount of dissipated heat from the skin or the level of heat exchange through the skin is by evaluating the surface temperature using IRT devices, as shown by Pereira et al. [17][15]. In this study, the authors compared the tail and coat surface temperature of female Mediterranean buffaloes raised at two different temperature ranges: a group in 24–27 °C, and another group with higher temperatures between 27 and 35 °C. The results showed that higher environmental temperatures increased the tail (32.83–35.13 °C vs. 34.15–37.96 °C, respectively), and coat temperatures (30.22–34.28 °C vs. 33.20–38.94 °C, respectively).

Although peripheral vasodilation highly modulates heat loss to prevent hyperthermia, it also causes compensatory tachycardia and tachypnea in buffaloes, which also serve as evaporative heat loss mechanisms [14,43][12][40]. The studies conducted by Silva et al. [51][50] reported that female Murrah buffaloes raised in non-shaded paddocks had higher respiratory movements per minute (mov/min) (29.2–34.4 mov/min) than buffaloes with access to shade (28.5–32.6 mov/min).

3.2. Anatomical Aspects

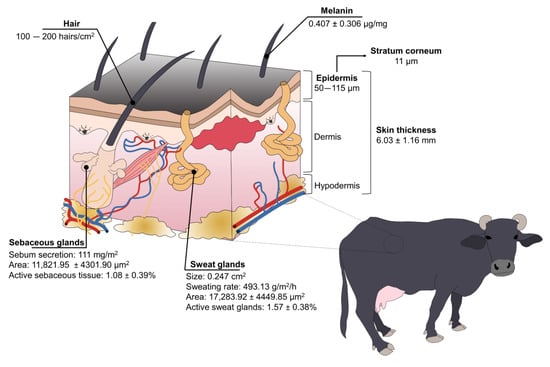

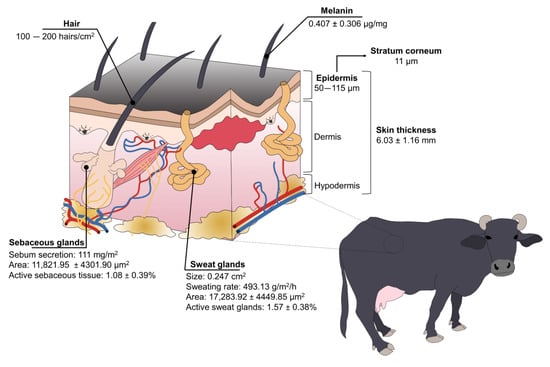

It is known that, compared to Bos taurus and indicus, water buffaloes trigger an intense physiological response to direct solar radiation due to anatomical traits such as the color and thickness of the epidermis, hair density, and number of sweat glands (Figure 3) [17,25][15][23]. The skin structure has a key role in buffaloes’ thermoregulation due to the sympathetic innervation (including thermoreceptors) that perceives and transmits stimulus to the POA [44][41].

Figure 3.

Structure and species-specific characteristics of water buffaloes’ skin.

Buffaloes have a high concentration of melanin in the basal cells of the skin and hair [21,57][19][51], with an average of 0.407 ± 0.306 µg/mg and 2.734 ± 2.409 µg/mg, respectively, in Taiwanese water buffaloes [58][52]. While the color of their skin protects them from ultraviolet radiation—and potentially skin tumors—in tropical regions, it also makes them more susceptible to heat stress because dark-colored skin/coats absorb higher concentrations of radiation [16,19][14][17]. Nonetheless, buffaloes have other anatomical adaptations to compensate for this susceptibility.

The skin thickness of buffaloes greatly differs when compared to cattle. Vilela et al. [15][13] determined that buffaloes’ skin thickness is 6.03 ± 1.16 mm. It is known that the thickness of the epidermis (50–115 µm) represents 1.5–2% of total skin [57][51], with a stratum corneum of 11 µm [25[23][53][54],59,60], while cattle have 51 µm and 5 µm of thickness, respectively [57][51]. From a thermoregulatory perspective, this suggests that the thick skin of water buffaloes acts as a thermal insulator against hot air [57][51].

Improving heat dissipation through skin blood vessels is also associated with their sparsely distributed hair [17][15]. Contrary to Bos genus having approximately 1000 hairs/cm2, water buffaloes have 100–200 hairs/cm2 [57][51]. Female Murrah buffaloes have an average hair density of 2.0 ± 0.26 mm2 [15][13]. While some authors mention that this characteristic makes them susceptible to solar radiation absorption [17][15], Presicce [57][51] refers to the low density of hair as a trait that facilitates heat loss via convection and radiation, preventing heat stress.

Water buffaloes also have a reduced density of sweat glands because these are highly correlated with the number of hair follicles [21][19]. Sweat glands were characterized in Murrah buffaloes, finding that the height of the sweat glands, the area, and the active sweat gland tissue was 16.2 ± 1.99 μm, 17,283.92 ± 4449.85 μm2, and 1.57 ± 0.38%, respectively [15][13]. It is said that buffaloes have a less efficient evaporative mechanism to dissipate heat due to their reduced sweating ability [16][14]. Nonetheless, buffaloes’ sweat glands are twice the size of the Bos species (0.247 cm2 vs. 0.124 cm2), possibly compensating for the lack of functional glands [57][51].

4. Behavioral Responses of Water Buffaloes to Diminish Heat Stress

4.1. Water Immersion

When animals are outside of their thermoneutral zone, which is defined as the environmental temperature range in which the species is in thermal comfort, a series of adaptive thermoregulatory mechanisms are triggered to promote heat loss and maintain the balance between the amount of produced heat via metabolic processes with the one that must be dissipated [21,62,63,64,65,66][19][55][56][57][58][59]. This is relevant because when animals are not able to dissipate heat to reduce their core temperatures, this results in a decreased food intake, low weight gain, and even fertility issues [67][60]. Within the behavioral responses that water buffaloes use to dissipate heat, water immersion can be listed. When buffaloes have free access to water through ponds, puddles, or potholes, they tend to spend a large part of the day wallowing, dedicating up to 2.35 h a day to this activity [66,68][59][61]. This phenomenon has been studied by Maykel et al. [66][59], who compared the influence of moderate vs. intense heat on the thermoregulatory behaviors and feeding changes of buffalo heifers in a silvopastoral system and a conventional system in Cuba. The authors found that the activity of immersing themselves in a pond of water was more frequent in buffaloes exposed to intense heat (>35 °C), spending an average of 4.06 h performing this activity, while buffaloes exposed to moderate heat spent 2.91 h inside the water.4.2. Seeking Shade

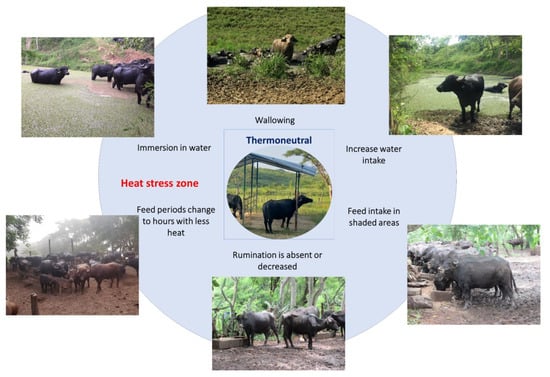

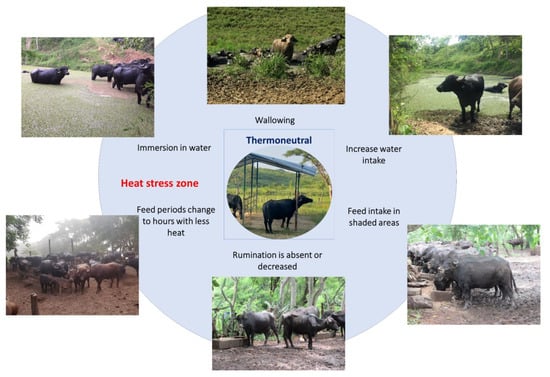

Another behavior that has been observed in buffaloes is seeking shaded areas, whether natural or artificial. When exposed to heat stress, water buffaloes tend to search for shaded areas that help them reduce their RT [70][62]. Moreover, the feed intake is influenced by the presence of shaded areas since it was reported that buffaloes prefer to graze in temperate climates while reducing foraging and rumination when exposed to heat stress [63,71][56][63]. Contrarily to food intake, water consumption increases, and other postural changes such as stretching body extremities are present as ways to dissipate heat [73][64]. In this sense, decreasing the time spent lying down and standing up exposes a greater amount of skin to air currents, maximizing evaporation [65][58]. This behavior can increase by up to 10% when heat loads above 15% are present, as mentioned by Tucker et al. [74][65]. Thermoregulatory behaviors are schematized in Figure 4 [20,65,73,75][18][58][64][66].

Figure 4. Thermoregulatory behaviors of water buffaloes when exceeding their thermoneutral zone. When the thermoneutral zone of the animals is exceeded and they begin a process of thermal discomfort, they present a series of behaviors to increase heat dissipation. For water buffaloes, the most common thermoregulatory behaviors are immersing themselves in flood zones, wallowing in mud, searching for shaded areas, and modifying their feed intake schedules or reducing their feed intake.

5. Influence of Natural/Artificial Shade on Buffaloes’ Thermoregulation

Farm facility improvement to reduce thermal sensation is considered a passive cooling design, where the use of the natural surroundings and the climate, without electronic devices, results in friendly and sustainable options for buffalo farms. Shed designs with particular attention to indoor ventilation, pre-cooled air entering the building, and envelope designs have been shown to reduce the indoor temperature by more than 5 °C in cattle farms [76][67].

Other techniques to promote normothermia include the use of wallowing areas or showers during summer [16][14], where water as a resource for heat dissipation facilitates heat exchange between the animal and the environment [21,77][19][68]. Silvopastoral systems (pastures combined with trees) are efficient alternatives in the tropics to reduce the effects of heat stress compared to conventional systems (only pastures). This was studied by Galloso-Hernández et al. [66][59], who evaluated the behavior of buffaloes under both types of production systems between May (intense heat stress) and November (moderate heat stress), both with access to a wallowing area. The results showed that the temperature was 2 °C lower in the silvopastoral system during intense heat stress and that behaviors such as grazing were significantly higher (7.49 vs. 5.96 h) during periods of intense heat stress.

On the other hand, Younas et al. [78][69] studied the physiological effect of artificial shade and other elements (e.g., ceiling fans and showers plus ceiling fans) on serological and thyroid hormones in Nili-Ravi buffaloes. The results showed that the use of showers and fans significantly decreased the skin temperature (decreases of up to 2.2%) (p < 0.05), RR (breaths per minute decreased by 17%), and pulse (decreases of up to 13.77%) over the other groups. Likewise, this group expressed the highest values in the thyroid analysis, which indicates a normal function of the thyroid gland, a function that can be affected by heat stress [78][69]. The milk yield is another parameter that can be affected by heat stress, and decreases have been reported.

Although access to water contributes to homeothermy, in places with water scarcity, this could represent a disadvantage. However, it was shown that providing shade can contribute to a reduction of 30% in radiated heat [16,20,80][14][18][70]. This can be reflected in a lower RR, plasma cortisol, heart pulse, and RT in animals provided with shaded areas. This was reported by Kumar et al. [81][71], who assessed the effect of housing modification on Murrah buffaloes. Two different housing conditions were compared: buffaloes under a loose housing system and buffaloes that were assigned to a shed with an asbestos roof that was 10–12 feet high, provided with sand bedding and ceiling fans. The results indicated that the buffaloes assigned under the open system had significantly higher RT (38.26 vs. 38.64 °C) and skin temperature values (35.10 vs. 33.89 °C) during autumn. Likewise, in contrast to the loose system, the buffaloes in the shed with the ceiling fans had lower RR (37.39 vs. 30.99 counts/min), pulse rate (60.91 vs. 52.52 counts/min), and cortisol levels (4.94 vs. 3.31 ng/mL), which could indicate that the use of sheds, roofs, sand bedding, and fans can decrease physiological reactions to heat stress. Moreover, it is important to consider that the use of asbestos is controversial due to its association with cancer. Reports indicate that commonly used roofing materials include a galvanized iron sheet [82][72] and thatched roofing [83,84][73][74]. Nonetheless, studies show significant differences between shade materials.

6. Thermal Imaging Applied to Evaluate Buffaloes’ Thermal States

IRT is a tool that is currently widely used in several disciplines such as engineering, construction, and both human and animal medicine [94][75]. It assesses the surface temperature of the skin as the vasomotor response of the organism to dissipate or conserve heat depending on the thermal state of the animals (i.e., hyperthermia or hypothermia) [95][76]. Currently, IRT is being applied in veterinary medicine as a real-time method to evaluate hemodynamic changes and the thermostability of animals due to thermal stress, inflammatory processes, pain, stressor exposure, and during different conditions and events (e.g., newborns or during transport) in a wide variety of species [14,55,95,96,97,98,99][12][76][77][78][79][80][81]. Regarding the auricular region, Sevegnani et al. [104][82] evaluated the thermoregulatory response in fifteen dairy Murrah buffaloes in the pre-milking and post-milking periods. They observed that the ear surface temperature, neck temperature, forehead temperature, and back shank temperature increased by 5–12 °C during post-milking. However, the surface temperature in regions such as the flanks and neck were mainly influenced by environmental conditions such as the THI and air temperature. This can lead us to question the usefulness of evaluating the temperature in these regions that are susceptible to environmental changes, contrarily to central windows such as the ocular temperature. Other regions such as the limbs and horns have also been proposed as thermal windows that are sensitive to heat loss, and examining these regions might serve as a method to recognize hyperthermia or hypothermia processes [111][83]. For example, Napolitano et al. [14][12] reported in 109 newborn water buffaloes that the surface temperature in the pelvic limb was 5 °C lower compared to other anatomical regions such as the lacrimal caruncle, periocular, dorsum, or auditory canal during the first five days post calving. Hypothermia is an event that can be present in newborns from different species, as shown in newborn puppies, in whom hypothermia leads to peripheral vasoconstriction of the dorsal metatarsal artery to prevent heat loss [112,113][84][85]; this is a similar physiological response as the one observed in buffaloes and can be indirectly evaluated through IRT. However, up to now, the association between thermal stress and these thermal windows has not been clearly established.References

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The Science of Climate Change. Available online: https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/climatechange/science (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Shraddha, R.; Nain, A.S. Impact of weather variables on Milk Production of Buffaloes. J. Agrometeorol. 2014, 16, 90–94.

- Bernabucci, U. Climate change: Impact on livestock and how can we adapt. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 3–5.

- Wolfenson, D.; Roth, Z.; Meidan, R. Impaired reproduction in heat-stressed cattle: Basic and applied aspects. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2000, 60–61, 535–547.

- Rawat, S.; Nain, A.S.; Roy, S. Biometeorological aspects of conception rate in cattle. J. Agrometeorol. 2014, 16, 116–120.

- Thornton, P.; Nelson, G.; Mayberry, D.; Herrero, M. Impacts of heat stress on global cattle production during the 21st century: A modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e192–e201.

- Cartwright, S.L.; Schmied, J.; Karrow, N.; Mallard, B.A. Impact of heat stress on dairy cattle and selection strategies for thermotolerance: A review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1198697.

- El Debaky, H.A.; Kutchy, N.A.; Ul-Husna, A.; Indriastuti, R.; Akhter, S.; Purwantara, B.; Memili, E. Review: Potential of water buffalo in world agriculture: Challenges and opportunities. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 35, 255–268.

- Sinha, A. Global Warming: Why India Is Heating Up Slower than the World Average. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-climate/climate-change-why-india-is-heating-up-slower-than-the-world-average-8602414/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Imran, Z. The “Press and Pulse” of Climate Change Strains Farmers in Pakistan. Available online: https://thebulletin.org/2023/02/the-press-and-pulse-of-climate-change-strains-farmers-in-pakistan/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Data, W. The Climate in China. Available online: https://www.worlddata.info/asia/china/climate.php (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Napolitano, F.; Bragaglio, A.; Braghieri, A.; El-Aziz, A.H.A.; Titto, C.G.; Villanueva-García, D.; Mora-Medina, P.; Pereira, A.M.F.; Hernández-Avalos, I.; José-Pérez, N.; et al. The effect of birth weight and time of day on the thermal response of newborn water buffalo calves. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1084092.

- Vilela, R.A.; Lourenço Junior, J.D.B.; Jacintho, M.A.C.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; Pantoja, M.H.D.A.; Oliveira, C.M.C.; Garcia, A.R. Dynamics of Thermolysis and Skin Microstructure in Water Buffaloes Reared in Humid Tropical Climate—A Microscopic and Thermographic Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 871206.

- Marai, I.F.M.F.M.; Haeeb, A.A.M.A.M. Buffalo’s biological functions as affected by heat stress—A review. Livest. Sci. 2010, 127, 89–109.

- Pereira, A.M.F.; Vilela, R.A.; Titto, C.G.; Leme-dos-Santos, T.M.C.; Geraldo, A.C.M.; Balieiro, J.C.C.; Calviello, R.F.; Birgel Junior, E.H.; Titto, E.A.L. Thermoregulatory Responses of Heat Acclimatized Buffaloes to Simulated Heat Waves. Animals 2020, 10, 756.

- Zhang, Y.; Colli, L.; Barker, J.S.F. Asian water buffalo: Domestication, history and genetics. Anim. Genet. 2020, 51, 177–191.

- Berihulay, H.; Abied, A.; He, X.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Adaptation mechanisms of small ruminants to environmental heat stress. Animals 2019, 9, 75.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Habeeb, A.A.; Napolitano, F.; Sarubbi, J.; Ghezzi, M.D.; Ceriani, M.C.; Cuibus, A.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Braghieri, A.; Lendez, P.A.; et al. Bienestar del búfalo de agua, bovino europeo y bovino índico: Aspectos medioambientales, fisiológicos y conductuales en respuesta a la sombra natural y artificial. In El Búfalo de Agua en Latinoamérica. Hallazgos Recientes; Napolitano, F., Mota-Rojas, D., Guerrero-Legarreta, I., Orihuela, A., Eds.; B.M. Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; pp. 959–1015. Available online: https://www.lifescienceglobal.com/journals/journal-of-buffalo-science/97-abstract/jbs/4550-el-bufalo-de-agua-en-latinoamerica-hallazgos-recientes (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Garcia, A.R.; Silva, L.K.X.; Barros, D.V.; de, B. Lourenço Junior, J.; Martorano, L.G.; Lisboa, L.S.S.; da Silva, J.A.R.; de Sousa, J.S.; da Silva, A.O.A. Key points for the thermal comfort of water buffaloes in Eastern Amazon. Ciênc. Rural 2023, 53, e20210544.

- Meissner, H.H.; Blignaut, J.N.; Smith, H.J.; Toit, C.J.L. The broad-based eco-economic impact of beef and dairy production: A global review. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 53, 250–275.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Álvarez-Macías, A.; Reyes, B.; Bertoni, A.; Peinado, S.F.; Flores, K.; Galarza, A.; Herrera, Y.; Torres, F.; Legarreta, I.G. La producción animal y el cambio climático. In Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación en la Industria Cárnica I; Guerrero-Legarreta, I., Ed.; Editorial Académica Española: London, UK, 2020; pp. 9–52.

- Da Silva, W.C.; Printes, O.V.N.; Lima, D.O.; da Silva, É.B.R.; dos Santos, M.R.P.; Camargo Júnior, R.N.C.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; da Silva, J.A.R.; e Silva, A.G.M.; Silva, L.K.X.; et al. Evaluation of the temperature and humidity index to support the implementation of a rearing system for ruminants in the Western Amazon. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1198678.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Pereira, A.M.F.; Wang, D.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Ghezzi, M.; Hernández-Avalos, I.; Lendez, P.; Mora-Medina, P.; Casas, A.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; et al. Clinical Applications and Factors Involved in Validating Thermal Windows Used in Infrared Thermography in Cattle and River Buffalo to Assess Health and Productivity. Animals 2021, 11, 2247.

- Zucali, M.; Tamburini, A.; Sandrucci, A.; Bava, L. Global warming and mitigation potential of milk and meat production in Lombardy (Italy). J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 474–482.

- Balhara, A.K.; Nayan, V.; Dey, A.; Singh, K.P.; Dahiya, S.S.; Singh, I. Climate change and buffalo farming in major milk producing states of India. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 87, 403–411.

- ONU. Paz, Dignidad e Igualdad en un Planeta Sano; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 1.

- Gerber, P.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Djikman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock—A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Das, S. Impact of climate change on livestock, various adaptive and mitigative measures for sustainable Livestock Production. Approaches Poult. Dairy Vet. Sci. 2017, 1, 64–70.

- Das, K.S.; Singh, J.K.; Singh, G.; Upadhyay, R.C.; Malik, R.; Oberoi, P.S. Heat stress alleviation in lactating buffaloes: Effect on physiological response, metabolic hormone, milk production and composition. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 84, 275–280.

- De Sousa, K.T.; Deniz, M.; do Vale, M.M.; Dittrich, J.R.; Hötzel, M.J. Influence of microclimate on dairy cows’ behavior in three pasture systems during the winter in south Brazil. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 97, 102873.

- Kiktev, N.; Lendiel, T.; Vasilenkov, V.; Kapralyuk, O.; Hutsol, T.; Glowacki, S.; Kuboń, M.; Kowalczyk, Z. Automated Microclimate Regulation in Agricultural Facilities Using the Air Curtain System. Sensors 2021, 21, 8182.

- Seerapu, S.R.; Kancharana, A.R.; Chappidi, V.S.; Bandi, E.R. Effect of microclimate alteration on milk production and composition in Murrah buffaloes. Vet. World 2015, 8, 1444–1452.

- Sigdel, A.; Bhattarai, N.; Kolachhapati, M.R. Impacts of climate change on Milk Production of Murrah buffaloes in Kaski, Nepal. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and Resilience for Sustainable Livelihood, Kathmandu, Nepal, 12–14 January 2015; pp. 205–207.

- Shahbaz, P.; Boz, I.; ul Haq, S. Adaptation options for small livestock farmers having large ruminants (cattle and buffalo) against climate change in Central Punjab Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 17935–17948.

- Di Stasio, L.; Brugiapaglia, A. Current Knowledge on River Buffalo Meat: A Critical Analysis. Animals 2021, 11, 2111.

- Bragaglio, A.; Maggiolino, A.; Romano, E.; De Palo, P. Role of Corn Silage in the Sustainability of Dairy Buffalo Systems and New Perspective of Allocation Criterion. Agriculture 2022, 12, 828.

- Guerrero-Legarreta, I.; Napolitano, F.; Cruz-Monterrosa, R.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Mora-Medina, P.; Ramírez-Bribiesca, E.; Bertoni, A.; Berdugo-Gutiérrez, J.; Braghieri, A. River buffalo meat production and quality: Sustainability, productivity, nutritional and sensory properties. J. Buffalo Sci. 2020, 9, 159–169.

- Álvarez-Macías, A.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Bertoni, A.; Dávalos-Flores, J.L. Opciones de desarrollo de los sistemas de producción de búfalos de agua de doble propósito en el trópico húmedo latinoamericano. In El búfalo de agua en Latinoamérica, Hallazgos Recientes; Napolitano, F., Mota-Rojas, D., Guerrero-Legarreta, I., Orihuela, A., Eds.; BM Editores: Mexico City, México, 2020; pp. 43–74. Available online: https://www.lifescienceglobal.com/journals/journal-of-buffalo-science/97-abstract/jbs/4550-el-bufalo-de-agua-en-latinoamerica-hallazgos-recientes (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Kandeepan, G.; Anjaneyulu, A.S.R.; Kondaiah, N.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Lakshmanan, V. Effect of age and gender on the processing characteristics of buffalo meat. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 10–14.

- Collier, R.J.; Baumgard, L.H.; Zimbelman, R.B.; Xiao, Y. Heat stress: Physiology of acclimation and adaptation. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 12–19.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Titto, C.G.; Orihuela, A.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Gómez-Prado, J.; Torres-Bernal, F.; Flores-Padilla, K.; Carvajal-de la Fuente, V.; Wang, D.; la Fuente, V.C.; et al. Physiological and Behavioral Mechanisms of Thermoregulation in Mammals. Animals 2021, 11, 1733.

- Wang, T.A.; Teo, C.F.; Åkerblom, M.; Chen, C.; Tynan-La Fontaine, M.; Greiner, V.J.; Diaz, A.; McManus, M.T.; Jan, Y.N.; Jan, L.Y. Thermoregulation via Temperature-Dependent PGD2 Production in Mouse Preoptic Area. Neuron 2019, 103, 309–322.e7.

- Nakamura, K. Central circuitries for body temperature regulation and fever. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 301, R1207–R1228.

- Nazıroğlu, M.; Braidy, N. Thermo-Sensitive TRP Channels: Novel Targets for Treating Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Pain. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1040.

- Lezama-García, K.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Pereira, A.M.F.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Ghezzi, M.; Domínguez, A.; Gómez, J.; de Mira Geraldo, A.; Lendez, P.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; et al. Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) and Thermoregulation in Animals: Structural Biology and Neurophysiological Aspects. Animals 2022, 12, 106.

- Morgan, M.; Nencini, S.; Thai, J.; Ivanusic, J.J. TRPV1 activation alters the function of Aδ and C fiber sensory neurons that innervate bone. Bone 2019, 123, 168–175.

- Zhao, Z.-D.; Yang, W.Z.; Gao, C.; Fu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, W.; Ni, X.; Lin, J.-K.; Yang, J.; et al. A hypothalamic circuit that controls body temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2042–2047.

- Morrison, S.F.; Nakamura, K. Central Mechanisms for Thermoregulation. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019, 81, 285–308.

- Shafton, A.D.; McAllen, R.M. Location of cat brain stem neurons that drive sweating. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 304, R804–R809.

- Da Silva, J.A.R.; de Araújo, A.A.; Lourenço Júnior, J.D.B.; Santos, N.D.F.A.D.; Garcia, A.R.; Nahúm, B.D.S. Conforto térmico de búfalas em sistema silvipastoril na Amazônia Oriental. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2011, 46, 1364–1371.

- Pressicce, G.A. The Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis): Production and Research; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2017.

- Pi-Hua, C.; Cheng-Yung, L.; Ching-Feng, W. The comparison of histology and melanin contents of hairs and skin between the black and white Taiwan water buffalo. J. Taiwan Livest. Res. 2009, 42, 235–244.

- Debbarma, D.; Uppal, V.; Bansal, N.; Gupta, A. Histomorphometrical Study on Regional Variation in Distribution of Sweat Glands in Buffalo Skin. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 5345390.

- Hafez, E.S.E.; Badreldin, A.L.; Shafei, M.M. Skin structure of Egyptian buffaloes and cattle with particular reference to sweat glands. J. Agric. Sci. 1955, 46, 19–30.

- El Sabry, M.; Almasri, O. Space allowance: A tool for improving behavior, milk and meat production, and reproduction performance of buffalo in different housing systems—A review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 7–10.

- Galloso-Hernández, M.A.; Rodríguez-Estévez, V.; Alvarez-Díaz, C.A.; Soca-Pérez, M.; Dublin, D.; Iglesias-Gómez, J.; Simon Guelmes, L. Effect of Silvopastoral Systems in the Thermoregulatory and Feeding Behaviors of Water Buffaloes Under Different Conditions of Heat Stress. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 393.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Habeeb, A.; Ghezzi, M.D.; Kanth, P.; Napolitano, F.; Lendez, P.A.; Cuibus, A.; Ceriani, M.C.; Sarubbi, J.; Braghieri, A.; et al. Termorregulación del búfalo de agua: Mecanismos neurobiológicos, cambios microcirculatorios y aplicaciones prácticas de la termografía infrarroja. In El Búfalo de Agua en Latinoamérica, Hallazgos Recientes; Napolitano, F., Mota-Rojas, D., Guerrero-Legarreta, I., Orihuela, A., Eds.; BM Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; pp. 923–958.

- Das Amit, M.; Dash, S.S.; Sahu, S.; Sarangi, A.; Singh, M. Effect of microclimate on feeding, drinking and physiological parameters of buffalo: A review. Pharma Innov. J. 2021, 10, 2416–2419.

- Galloso-Hernández, M.A.; Soca-Pérez, M.; Dublin, D.; Alvarez-Díaz, C.A.; Iglesias-Gómez, J.; Díaz-Gaona, C.; Rodríguez-Estévez, V. Thermoregulatory and feeding behavior under different management and heat stress conditions in heifer water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) in the tropics. Animals 2021, 11, 1162.

- Joksimovic-Todorovic, M.; Davidovic, V.; Hristov, S.; Stankovic, B. Effect of heat stress on milk production in dairy cows. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2011, 27, 1017–1023.

- Napolitano, F.; Pacelli, C.; Grasso, F.; Braghieri, A.; De Rosa, G. The behaviour and welfare of buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in modern dairy enterprises. Animal 2013, 7, 1704–1713.

- Koga, A.; Chanpongsang, S.; Chaiyabutr, N. Importance of body-water circulation for body-heat dissipation in hot-humid climates: A distinctive body-water circulation in swamp buffaloes. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 6, 1219–1222.

- Da Silva, J.A.R.; de, A. Pantoja, M.H.; da Silva, W.C.; de Almeida, J.C.F.; de P.P. Noronha, R.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; de B. Lourenço Júnior, J. Thermoregulatory reactions of female buffaloes raised in the sun and in the shade, in the climatic conditions of the rainy season of the Island of Marajó, Pará, Brazil. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 998544.

- Galloso, H.M.A. Potencial de los Sistemas Silvopastoriles para la Producción Bufalina en Ambientes Tropicales; UCO Press: Córdoba, Spain, 2021.

- Tucker, C.B.; Rogers, A.R.; Schütz, K.E. Effect of solar radiation on dairy cattle behaviour, use of shade and body temperature in a pasture-based system. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 109, 141–154.

- De, S. Ablas, D.; Titto, E.A.; Pereira, A.M.; da C. Leme, T.M. Comportamento de bubalinos a pasto frente a disponibilidade de sombre e água para imersao. Braz. Anim. Sci. 2007, 8, 167–176.

- Tikul, N.; Prachum, S. Passive cooling strategies for cattle housing on small farms: A case study. Maejo Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 25–39.

- De Souza, D.; Manuel Franco Pereira, A.; Gonçalves, C.; Da Cunha Leme, M. Comportamento De Bubalinos a Pasto Frente a Disponibilidade De Sombra E Água Para Imersão. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2007, 8, 167–175.

- Younas, U.; Abdullah, M.; Bhatti, J.A.; Ahmed, N.; Shahzad, F.; Idris, M.; Tehseen, S.; Junaid, M.; Tehseen, S.; Ahmed, S. Biochemical and physiological responses of Nili-Ravi Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) to heat stress. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2020, 44, 1196–1202.

- Aggarwal, A.; Upadhyay, R. Shelter management for alleviation of heat stress in cows and buffaloes. In Heat Stress and Animal Productivity; Aggarwal, A., Upadhyay, R., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 169–183.

- Kumar, A.; Kamboj, M.L.; Chandra, S.; Bharti, P. Effect of modified housing system on physiological parameters of Murrah buffaloes during autumn and winter season. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2017, 52, 829–833.

- Vranda, R.; Satyanarayan, K.; Jagadeeswary, V.; Veeranna, K.C.; Rajeshwari, Y.B.; Sudha, G.; Shree, J.S. A Study on Different Housing Practices of Buffaloes in Bidar District of Karnataka. Int. J. Sci. Environ. Technol. 2017, 6, 295–302.

- Patel, N.S.; Patel, J.V.; Parmar, D.V.; Ankuya, K.J.; Patel, V.K.; Madhavatar, M.P. Survey on housing practices of buffaloes owners in Patan district of Gujarat, India. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2019, 7, 635–640.

- Mote, M.G.; Dhumal, P.T.; Gaikwad, U.S. Housing management practices followed by Buffalo owners in Purandar Tehsil of Pune district. Indian J. Anim. Prod. Manag. 2021, 36, 36–40.

- Casas-Alvarado, A.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Mora-Medina, P.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Verduzco-Mendoza, A.; Reyes-Sotelo, B.; Martínez-Burnes, J. Advances in infrared thermography: Surgical aspects, vascular changes, and pain monitoring in veterinary medicine. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 92, 102664.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Gómez-Prado, J.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Lezama-García, K.; Jacome-Romero, J.; Rodríguez-González, D.; Pereira, A.M.F. Clinical usefulness of infrared thermography to detect sick animals: Frequent and current cases. CABI Rev. 2022, 17, 1–17.

- Rodríguez-González, D.; Guerrero-Legarreta, I.; Cruz Monterrosa, R.G.; Napolitano, F.; Gonçalves-Titto, C.; El-Aziz, A.H.A.; Hernández- Ávalos, I.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Oliva- Domínguez, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. Assessment of thermal changes in water buffalo mobilized from the paddock and transported by short journeys. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1184577.

- José-Pérez, N.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Ghezzi, M.D.; Rosmini, M.R.; Mora-Medina, P.; Bertoni, A.; Rodríguez-González, D.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Guerrero-Legarreta, I. Effects of transport on water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis): Factors associated with the frequency of skin injuries and meat quality. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2022, 10, 2216.

- Reyes-Sotelo, B.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; José, N.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Gómez, J.; Mora-Medina, P. Thermal homeostasis in the newborn puppy: Behavioral and physiological responses. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2021, 9, 21012.

- Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Villegas-Juache, J.; Verduzco-Mendoza, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. Thermal response of laboratory rats (Rattus norvegicus) during the application of six methods of euthanasia assessed by infrared thermography. Animals 2023, 13, 2820.

- Da Silva, W.C.; da Silva, J.A.R.; da Silva, É.B.R.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; Sousa, C.E.L.; de Carvalho, K.C.; dos Santos, M.R.P.; Neves, K.A.L.; Martorano, L.G.; Camargo Júnior, R.N.C.; et al. Characterization of Thermal Patterns Using Infrared Thermography and Thermolytic Responses of Cattle Reared in Three Different Systems during the Transition Period in the Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Animals 2023, 13, 2735.

- Sevegnani, K.B.; Fernandes, D.P.B.; da Silva, S.H.M.-G. Evaluation of thermorregulatory capacity of dairy buffaloes using infrared thermography. Eng. Agrícola 2016, 36, 1–12.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Wang, D.D.-H.; Titto, C.G.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Villanueva-García, D.; Lezama, K.; Domínguez, A.; Hernández-Avalos, I.; Mora-Medina, P.; Verduzco, A.; et al. Neonatal infrared thermography images in the hypothermic ruminant model: Anatomical-morphological-physiological aspects and mechanisms for thermoregulation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 963205.

- Lezama-García, K.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Marcet-Rius, M.; Gazzano, A.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Mora-Medina, P.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Pereira, A.M.F.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Baqueiro-Espinosa, U.; et al. Is the Weight of the Newborn Puppy Related to Its Thermal Balance? Animals 2022, 12, 3536.

- Reyes-Sotelo, B.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Mora-Medina, P.; Ogi, A.; Mariti, C.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Sánchez-Millán, J.; Gazzano, A. Blood Biomarker Profile Alterations in Newborn Canines: Effect of the Mother′s Weight. Animals 2021, 11, 2307.

More