Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lindsay Dong and Version 1 by Youssef Youssef.

Uterine Adenomyosis is a benign condition characterized by the presence of endometrium-like epithelial and stromal tissue in the myometrium. Several medical treatments have been proposed, but still, no guidelines directing the management of adenomyosis are available. While a hysterectomy is typically regarded as the definitive treatment for adenomyosis, the scarcity of high-quality data leaves patients desiring fertility with limited conservative options.

- adenomyosis

- medical treatments

- progesterone

- intrauterine devices

- gonadotropin releasing hormones

1. Introduction

Uterine Adenomyosis is a benign condition histologically defined as the presence of endometrium-like epithelial and stromal tissue in the myometrium, along with enlargement of the uterus [1,2][1][2]. Its prevalence is estimated to be around 1%, with an incidence of 29 per 10,000 person–years [3]. Like endometriosis and leiomyoma, adenomyosis is most identified in women aged 41–45 years and is more prominent in the African American population [1,2,3][1][2][3]. The exact etiology of adenomyosis remains unclear, despite multiple proposed theories, such as Müllerian rests, metaplasia of stem cells, genetic mutations, and endometrial invagination into the myometrium [4,5,6][4][5][6]. New theories related to endometriosis pathophysiology could change our current understanding of adenomyosis, as adenomyosis and endometriosis are closely linked, both being estrogen-dependent and often found concomitantly in patients [7,8,9][7][8][9]. One of these newer theories is that genetic-epigenetic changes affect intracellular aromatase activity causing intracellular estrogen production with the subsequent development of inflammatory, fibrotic endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus [10]. It is important to note that although adenomyosis and endometriosis share similar histological features and molecular changes, they differ in pathogenesis, location, and clinical features [11,12][11][12].

Adenomyosis presents clinically with debilitating symptoms such as menorrhagia, chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and infertility, requiring treatment [16][13]. Diagnosis of adenomyosis is made via transvaginal ultrasonography (US) or MRI but definitive diagnosis requires histopathological evidence. US findings include heterogeneous myometrium, myometrial cysts, and asymmetric myometrial thickness, in addition to sub-endometrial echogenic linear striations [17,18,19,20,21][14][15][16][17][18]. MRI findings include high-intensity foci representing hemorrhage and increased thickness of the junctional zone representing smooth muscle hyperplasia with accompanying heterotopic endometrial tissue [22][19]. Studies comparing the effectiveness of transvaginal US and MRI have demonstrated the latter to be equal, if not superior, in the diagnosis of adenomyosis [23,24,25,26,27][20][21][22][23][24].

Currently, no guidelines directing the management of adenomyosis are available, despite numerous treatments, both medical and surgical in nature [28,29][25][26]. Although hysterectomy provides a definitive cure, it is not the method of choice for patients willing to preserve future fertility or those who are not medically fit for surgery [30][27]. In light of the increasing trend of late childbearing, various pharmacological therapies and fertility-preserving surgeries have emerged.

2. Medical Therapies for Adenomyosis

3.1. Classical Treatments

2.1. Classical Treatments

32.1.1. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs have been proven to be effective in treating dysmenorrhea, despite insufficient evidence to determine the safest and most effective agent in that class [33][28]. A Cochrane database systematic review demonstrated a statistically relevant decrease in heavy menstrual bleeding when comparing NSAIDs to placebo, despite being less effective than hormonal treatments or tranexamic acid [34][29]. Nevertheless, NSAIDs and other analgesics remain the sole treatment option in women with adenomyosis interested in pregnancy [35][30]. In symptomatic women with no interest in conceiving, hormonal treatments are preferred to address chronic abnormal uterine bleeding and pain, with NSAIDS prescribed only in acute exacerbations [35][30].32.1.2. Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intra-Uterine Device (LNG-IUD)

LNG-IUDs diffusing 20 µg/day of levonorgestrel are often used in women with adenomyosis experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding, despite being originally designed for long-term contraception [35,36][30][31]. They exert their control via decidualization and atrophy of the endometrial tissue by creating a hypoestrogenic state and by downregulating estrogen receptors due to high progestin release [37,38][32][33]. Ozdegirmenci et al. found LNG-IUD to be comparable to hysterectomy after measuring hemoglobin levels at 6 months and 1 year of treatment [39][34]. LNG-IUDs are currently the best-evaluated and most efficacious treatment of adenomyosis-related symptoms with a high rate of symptom improvement, minimal sideeffects, and an improvement in the quality of life that is similar to that of a hysterectomy [35][30].32.1.3. Progestins

Progestins exert an anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effect, leading to the decidualization and atrophy of endometrial tissue, with a subsequent significant reduction in bleeding [28][25]. Dienogest (DNG) is a synthetic progestogen with properties of 19-norprogesterone and 17α-hydroxyprogesterone derivatives used in the long-term treatment of endometriosis [35][30]. It has been proven to improve primary and secondary dysmenorrhea [42][35]. Despite being used for the treatment of adenomyosis-related symptoms, there is currently no proper therapeutic management protocol for its use in the treatment of adenomyosis [28][25]. Danazol is a synthetic modified progestogen that reversibly inhibits the synthesis of LH and FSH and has a weak androgenic effect [45][36]. It is used in endometriosis to shrink ectopic endometrial tissue in addition to reducing aromatase expression in the eutopic endometrium [46][37].32.1.4. Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Agonist and Oral Contraceptive Pills (OCP)

GnRH is a decapeptide secreted by the hypothalamic neurons that acts on receptors in the anterior pituitary gland. Continuous prolonged stimulation by GnRH agonists leads to a central downregulation with the suppression of gonadotropin secretion, ultimately leading to the induction of a hypoestrogenic state in addition to an antiproliferative effect within the myometrium [51][38]. Additionally, combined oral contraceptive pills were found to be effective in treating dysmenorrhea [52][39]. Both OCPs and GnRH agonists are used as suppressive hormonal therapies to induce the regression of adenomyosis and improve the severity of symptoms [53][40]. GnRH agonists are also indicated to improve the chances of pregnancy in women with adenomyosis [56][41]. The highest pregnancy rate has been reported in women undergoing frozen embryo transfer after GnRH agonist treatment [57][42]. It is important to note, however, that the use of GnRH agonists for pain and bleeding should be restricted to short-term only due to possible menopausal effects [58][43].32.1.5. GnRH Antagonists

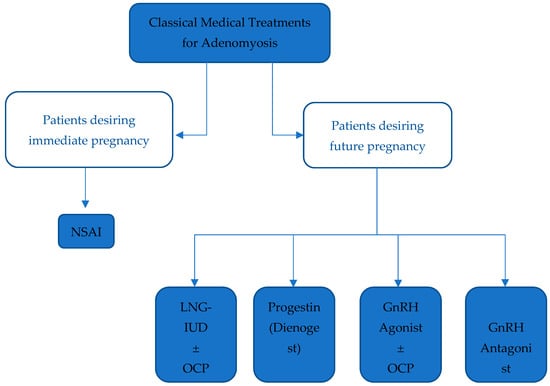

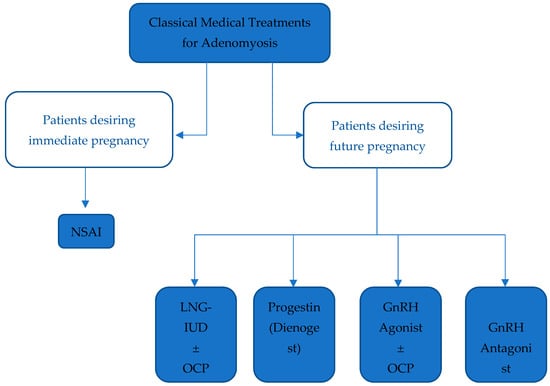

GnRH antagonists are peptide compounds that share a structure like that of natural GnRH and have an immediate antagonist effect on GnRH receptors in the pituitary gland, inhibiting gonadotropin secretion [35][30]. A case report by Donnez et al. describes a patient who, after failing a course of ulipristal acetate, a Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulator (SPRM), was prescribed Linzagolix, a GnRH antagonist. Treatment with Linzagolix reduced adenomyotic lesion size and dysmenorrhea burden, ultimately leading to improved quality of life [59][44]. Another GnRH antagonist, Elagolix, is currently being developed for the long-term treatment of endometriosis and uterine leiomyomas [55,60,61,62][45][46][47][48]. Elagolix has been shown to regress the size of fundal adenomyoma, with an improvement in clinical symptoms and the resolution of pelvic pain [63][49]. The main advantage of GnRH antagonists over GnRH agonists is their ability to maintain sufficient estradiol levels to avoid bone demineralization and estrogen deprivation symptoms [64][50] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summarizing classical medical treatments for Adenomyosis. Legend: NSAID: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, LNG-IUD: Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, OCP: Oral contraceptive pill, GnRH: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

3.2. Prospective and Future Treatments

2.2. Prospective and Future Treatments

32.2.1. Aromatase Inhibitors

Aromatase P450 is an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of androgens to estrogens. It is expressed physiologically in the granulosa cells of growing follicles amongst other cells [35][30]. Aromatase inhibitors that halt the production of estrogen are used in adenomyosis to suppress the hormonal medium favoring disease progression [65][51]. In their randomized control trial, Badawi et al. found GnRH agonists and aromatase inhibitors to be equally effective in reducing adenomyosis and symptoms burden [55][45]. Decreases in uterine and adenomyoma volumes were comparable among both treatment arms, suggesting that aromatase inhibitors are as effective as GnRH agonists [55][45]. When combined, however, both agents further reduced uterine volume by 60% on imaging after 8 weeks of treatment [66][52].32.2.2. Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulators (SPRMs)

SPRMs are modified synthetic steroids derived from norethindrone that can interact with progesterone receptors to either activate or repress gene transcription in a tissue-specific manner [35][30]. SPRMs have been proven to reduce the size of uterine fibroids, stop endometrial bleeding and changes, and suppress the luteinizing hormone peak while maintaining normal follicle-stimulating hormone levels [67,68,69,70,71,72][53][54][55][56][57][58]. The two most commonly prescribed SPRMs are Ulipristal acetate (UPA) and Mifepristone [35][30]. In a randomized control trial by Capmas et al., UPA was administered to a group of 30 women with adenomyosis who were then compared to a control group of 10 patients [73][59]. There was a significant decrease in the pictorial blood loss assessment chart in the treatment group, with 95.24% of patients scoring below 75, compared to scoring above 100 before the intervention (p < 0.01) [73][59]. Pain also improved after treatment; however, no significant differences in pain or blood loss were found at a 6-month follow-up [73][59]. Mifepristone is one of the first and most widely used SPRMs. Its affordability and low-risk profile can be of great advantage to patients since adenomyosis requires long-term medical therapy [76][60]. Wang et al. compared different dosages of mifepristone to a placebo. Their outcome of interest was the immunohistochemical expression of caspase-3 in the eutopic and ectopic endometrium in women with adenomyosis [77][61]. Their results showed an increase in caspase-3 expression in women treated with mifepristone. This finding suggests that mifepristone could induce eutopic and ectopic endometrial cells to undergo apoptosis by activating caspase-3 expression [77][61].32.2.3. Antiplatelet Therapy

Serial immunohistochemistry analyses of ectopic endometrium in mouse models demonstrated that platelet activation coincided with the induction of the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in adenomyosis, ultimately leading to fibrosis and smooth muscle metaplasia (Shen et al. unpublished data) [80,81][62][63]. These findings were similarly demonstrated in human adenomyosis [82][64].32.2.4. Dopamine Agonist

Adenomyosis in mice models can be stimulated hormonally by inducing hyperprolactinemia [84][65]. Prolactin and its receptors are increased in adenomyotic tissue, suggesting an association between prolactin and adenomyosis [85][66]. Bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist and prolactin inhibitor when administered orally, is recognized for its notable prevalence of adverse effects, leading to a 10% discontinuation rate among patients. Frequently reported side effects encompass gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, dizziness, sinus congestion, and alterations in orthostatic blood pressure and heart rate.32.2.5. Oxytocin Antagonists

Women experiencing primary dysmenorrhea have been found to have higher oxytocin and vasopressin plasma levels, inducing an increase in myometrial peristalsis via oxytocin receptors (OTR) and vasopressin V1a receptors [35][30]. Nie et al. demonstrated that the immunoreactivity of OTR was increased in endometrial stromal and epithelial cells in addition to myometrial and vascular cells in ectopic adenomyosis foci, concluding that OTR expression in epithelial cells was correlated with the severity of dysmenorrhea [88][67]. Atosiban, an OTR antagonist, has been proven to reduce myometrial contractility and pain symptoms in women with primary dysmenorrhea [89][68]. Epelsiban, another OTR antagonist, was tested on a population of healthy women and was found to be well tolerated [90][69]. Unfortunately, no further clinical studies have been published concerning Epelsiban.32.2.6. Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) Inhibition

STAT3 has been proven to highly affect endometrial tissue growth [12]. Hiraoka et al. investigated the influence of STAT3 on adenomyosis in a mouse model of adenomyosis and human specimens of eutopic endometria and adenomyotic lesions. They found that mice with eutopic and ectopic endometria demonstrated positive immunoreactivity for phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3), the active form of STAT3 [12].32.2.7. KRAS Genetically Guided Therapy

Inoue et al. applied next-generation sequencing to human adenomyosis samples, in addition to co-occurring leiomyoma and endometriosis, to evaluate the presence of somatic genomic alterations [13][70]. They found that KRAS mutations are more frequent in cases of adenomyosis with co-occurring endometriosis, low progesterone receptor expression, or dienogest pretreatment [13][70]. The authors suggested that KRAS status could be a biomarker of treatment efficacy, stating that lesions containing numerous KRAS mutations may reduce dienogest efficacy [13][70]. These findings could lead to genetically guided therapies and/or relapse risk assessment after uterine-sparing surgery [13][70].32.2.8. Qiu’s Neiyi Recipe

Qiu’s Neiyi recipe (Qiu) is a traditional Chinese medicine that has been used for endometriosis therapy in China for decades [92][71]. The advantages of using traditional Chinese medicine are usually milder adverse reactions, and relatively cost-efficient prices [93][72]. In their study on adenomyosis in mice models, Ying et al. hypothesized that the administration of Qiu might improve the inflammation in adenomyosis through the regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (MAPKs/ERKs) signaling pathway [94][73]. They demonstrated that Qiu treatment led to an improvement in symptoms by reducing myometrial infiltration, in addition to reduced levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in mice serum and uterine tissue [94][73].32.2.9. Micro RNA

MicroRNA therapy is a relatively new technology, with the first-ever small RNA-based therapeutic drug obtaining its FDA approval in 2018 [95][74]. MicroRNA therapy specifically targets and silences multiple genes, including those involved in disease development [96][75]. Several dysregulated microRNAs have been identified in the endometrium of adenomyosis patients [95][74]. This makes it reasonable to suggest the transcriptional regulation of dysregulated microRNA as a treatment for the disease [96][75].32.2.10. Valproic Acid

The current evidence concerning endometriosis and adenomyosis is leaning towards them being epigenetic diseases with aberrant methylation [65,97,98,99][51][76][77][78]. Considering these findings, both diseases could be addressed by using demethylating agents and histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs), such as valproic acid [100,101,102][79][80][81]. Valproic acid has known and favorable pharmacokinetic properties and has been used for decades to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorders [103,104][82][83].32.2.11. Levo-Tetrahydropalmatine (L-THP) and Andrographolide

L-THP and andrographolide are both active ingredients derived from Chinese medicinal herbs, used in traditional Chinese medicine [108][84]. L-THP is a known analgesic with a remarkable non-addictive sedative effect that has been reported to suppress uterine contraction in virgin rat models [108,109][84][85]. Additionally, L-THP was reported to significantly reduce lesion size and pain in rats with induced endometriosis [110][86]. Andrographolide is a potent nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) inhibitor used as an anti-inflammatory agent [108][84]. Reports have emerged stating that NF-kB p65 subunit expression is elevated in adenomyosis, suggesting that NF-kB is constitutively activated in adenomyosis [111][87].32.2.12. VEGF Inhibitors

Angiogenesis plays a pivotal role in the implantation and development of ectopic endometrial lesions. The potential therapeutic usefulness of Bevacizumab (Avastin®), a monoclonal antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth (VEGF), in endometriosis has been speculated. Animal experiments showed beneficial effects both in the treatment and prophylaxis of endometriosis relapse [65,110,111][51][86][87].43. Conclusions

Adenomyosis is a serious and debilitating disease that profoundly affects the quality of life and fertility of affected women. The current medical treatments for adenomyosis, include NSAIDs, LNG-IUDs, progestins, and combined OCPs, as well as both GnRH agonists and antagonists. Available data suggest that LNG-IUDs are the most well-evaluated and efficacious treatment for adenomyosis-related symptoms when compared to other oral agents. While Dienogest, which has been studied more extensively in endometriosis, still shows favorable outcomes in adenomyosis cases, the absence of a standardized protocol remains a challenge. GnRH agonists represent a second-line option with positive outcomes, but their hypoestrogenic side effects contribute to high discontinuation rates, necessitating add-back therapy for long-term use. Promising results have also emerged for GnRH antagonists, oxytocin, and prolactin modulators, yet further studies are imperative to assess their efficacy and establish standardized protocols.References

- Agostinho, L.; Cruz, R.; Osório, F.; Alves, J.; Setúbal, A.; Guerra, A. MRI for adenomyosis: A pictorial review. Insights Into Imaging 2017, 8, 549–556.

- Akira, S.; Mine, K.; Kuwabara, Y.; Takeshita, T. Efficacy of long-term, low-dose gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy (draw-back therapy) for adenomyosis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2008, 15, CR1–CR4.

- Andersson, J.K.; Khan, Z.; Weaver, A.L.; Vaughan, L.E.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Stewart, E.A. Vaginal bromocriptine improves pain, menstrual bleeding and quality of life in women with adenomyosis: A pilot study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 1341–1350.

- Andersson, J.K.; Mucelli, R.P.; Epstein, E.; Stewart, E.A.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K. Vaginal bromocriptine for treatment of adenomyosis: Impact on magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasound. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 254, 38–43.

- Ascher, S.M.; Arnold, L.L.; Patt, R.H.; Schruefer, J.J.; Bagley, A.S.; Semelka, R.C.; Zeman, R.K.; Simon, J.A. Adenomyosis: Prospective comparison of MR imaging and transvaginal sonography. Radiology 1994, 190, 803–806.

- Atri, M.; Reinhold, C.; Mehio, A.R.; Chapman, W.B.; Bret, P.M. Adenomyosis: US features with histologic correlation in an in-vitro study. Radiology 2000, 215, 783–790.

- Badawy, A.M.; Elnashar, A.M.; Mosbah, A.A. Aromatase inhibitors or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for the management of uterine adenomyosis: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 489–495.

- Bazot, M.; Cortez, A.; Darai, E.; Rouger, J.; Chopier, J.; Antoine, J.-M.; Uzan, S. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: Correlation with histopathology. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 2427–2433.

- Beatty, M.N.; Blumenthal, P.D. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: Safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 561.

- Bromley, B.; Shipp, T.D.; Benacerraf, B. Adenomyosis: Sonographic findings and diagnostic accuracy. J. Ultrasound. Med. 2000, 19, 529–534.

- Bulun, S.E.; Yildiz, S.; Adli, M.; Chakravarti, D.; Parker, J.B.; Milad, M.; Yang, L.; Chaudhari, A.; Tsai, S.; Wei, J.J.; et al. Endometriosis and adenomyosis: Shared pathophysiology. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 746–750.

- Burney, R.O.; Giudice, L.C. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 511–519.

- Che, X.; Wang, J.; He, J.; Guo, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, X. The new application of mifepristone in the relief of adenomyosis-caused dysmenorrhea. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 224–233.

- Chen, C.; Wu, D.; Guo, Z.; Xie, Q.; Reinhart, G.J.; Madan, A.; Wen, J.; Chen, T.; Huang, C.Q.; Chen, M. Discovery of Sodium R-(+)-4- butyrate (Elagolix), a Potent and Orally Available Nonpeptide Antagonist of the Human Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7478–7485.

- Chu, H.; Jin, G.; Friedman, E.; Zhen, X. Recent development in studies of tetrahydroprotoberberines: Mechanism in antinociception and drug addiction. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2007, 28, 491–499.

- Conway, F.; Morosetti, G.; Camilli, S.; Martire, F.G.; Sorrenti, G.; Piccione, E.; Zupi, E.; Exacoustos, C. Ulipristal acetate therapy increases ultrasound features of adenomyosis: A good treatment given in an erroneous diagnosis of uterine fibroids. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 207–210.

- Dessouky, R.; Gamil, S.A.; Nada, M.G.; Mousa, R.; Libda, Y. Management of uterine adenomyosis: Current trends and uterine artery embolization as a potential alternative to hysterectomy. Insights Into Imaging 2019, 10, 48.

- Di Donato, N.; Montanari, G.; Benfenati, A.; Leonardi, D.; Bertoldo, V.; Monti, G.; Raimondo, D.; Seracchioli, R. Prevalence of adenomyosis in women undergoing surgery for endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 181, 289–293.

- Diamond Michael, P.; Carr, B.; Dmowski, W.P.; Koltun, W.; O’Brien, C.; Jiang, P.; Burke, J.; Jimenez, R.; Garner, E.; Chwalisz, K. Elagolix treatment for endometriosis-associated pain: Results from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 21, 363–371.

- Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.-M. Uterine fibroid management: From the present to the future. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 665–686.

- Donnez, J.; Donnez, O.; Dolmans, M.-M. Safety of treatment of uterine fibroids with the selective progesterone receptor modulator, ulipristal acetate. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 1679–1686.

- Donnez, J.; Tatarchuk, T.F.; Bouchard, P.; Puscasiu, L.; Zakharenko, N.F.; Ivanova, T.; Ugocsai, G.; Mara, M.; Jilla, M.P.; Bestel, E.; et al. Ulipristal Acetate versus Placebo for Fibroid Treatment before Surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 409–420.

- Donnez, J.; Tomaszewski, J.; Vázquez, F.; Bouchard, P.; Lemieszczuk, B.; Baró, F.; Nouri, K.; Selvaggi, L.; Sodowski, K.; Bestel, E.; et al. Ulipristal Acetate versus Leuprolide Acetate for Uterine Fibroids. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 421–432.

- Donnez, J.; Vázquez, F.; Tomaszewski, J.; Nouri, K.; Bouchard, P.; Fauser, B.C.; Barlow, D.H.; Palacios, S.; Donnez, O.; Bestel, E.; et al. Long-term treatment of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1565–1573.e18.

- Donnez, O.; Donnez, J. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (linzagolix): A new therapy for uterine adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 640–645.

- Dueholm, M.; Lundorf, E.; Hansen, E.S.; Sørensen, J.S.; Ledertoug, S.; Olesen, F. Magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2001, 76, 588–594.

- Farquhar, C.; Brosens, I. Medical and surgical management of adenomyosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 20, 603–616.

- Gottlicher, M.; Minucci, S.; Zhu, P.; Kramer, O.H.; Schimpf, A.; Giavara, S.; Sleeman, J.P.; Coco, F.L.; Nervi, C.; Pelicci, P.G. The teratogen valproic acid defines a novel class of histone deacetylase inhibitors inducing differentiation of embryonic, transformed and tumorigenic cells. In Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; p. R148.

- Greaves, P.; White, I.N.H. Experimental adenomyosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 20, 503–510.

- Gruber, T.M.; Mechsner, S. Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: The Origin of Pain and Subfertility. Cells 2021, 10, 1381.

- Güzel, A.I.; Akselim, B.; Erkılınç, S.; Kokanalı, K.; Tokmak, A.; Dolmuş, B.; Doğanay, M. Risk factors for adenomyosis, leiomyoma and concurrent adenomyosis and leiomyoma. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2015, 41, 932–937.

- Hauksson, A.; Ekström, P.; Juchnicka, E.; Laudanski, T.; Åkerlund, M.; Åkerlund, D.M. The influence of a combined oral contraceptive on uterine activity and reactivity to agonists in primary dysmenorrhea. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1989, 68, 31–34.

- Herndon, C.N.; Aghajanova, L.; Balayan, S.; Erikson, D.; Bs, F.B.; Goldfien, G.; Vo, K.C.; Hawkins, S.; Giudice, L.C. Global Transcriptome Abnormalities of the Eutopic Endometrium from Women With Adenomyosis. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 23, 1289–1303.

- Hiraoka, T.; Hirota, Y.; Fukui, Y.; Gebril, M.; Kaku, T.; Aikawa, S.; Hirata, T.; Akaeda, S.; Matsuo, M.; Haraguchi, H.; et al. Differential roles of uterine epithelial and stromal STAT3 coordinate uterine receptivity and embryo attachment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15523.

- Igarashi, M.; Abe, Y.; Fukuda, M.; Ando, A.; Miyasaka, M.; Yoshida, M. Novel conservative medical therapy for uterine adenomyosis with a danazol-loaded intrauterine device. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 74, 412–413.

- Ishihara, H.; Kitawaki, J.; Kado, N.; Koshiba, H.; Fushiki, S.; Honjo, H. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and danazol normalize aromatase cytochrome P450 expression in eutopic endometrium from women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or leiomyomas. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 79, 735–742.

- Johannessen, C.U. Mechanisms of action of valproate: A commentatory. Neurochem. Int. 2000, 37, 103–110.

- Kitawaki, J. Adenomyosis: The pathophysiology of an oestrogen-dependent disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 20, 493–502.

- Koninckx, P.R.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L.; Tahlak, M.; Keckstein, J.; Wattiez, A.; Martin, D.C. The epidemiology of endometriosis is poorly known as the pathophysiology and diagnosis are unclear. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 71, 14–26.

- Lethaby, A.; Duckitt, K.; Farquhar, C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 19, CD000400.

- Liu, X.; Shen, M.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.-W. Corroborating evidence for platelet-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in the development of adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 734–749.

- Liu, X.; Guo, S.-W. A pilot study on the off-label use of valproic acid to treat adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 246–250.

- Liu, X.; Guo, S.-W. Valproic acid alleviates generalized hyperalgesia in mice with induced adenomyosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2011, 37, 696–708.

- Loo, M.H.; Egan, D.; Vaughan, E.D.; Marion, D.; Felsen, D.; Weisman, S. The Effect of the Thromboxane A2 Synthesis Inhibitor Oky-046 on Renal Function in Rabbits Following Release of Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction. J. Urol. 1987, 137, 571–576.

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, W. Doppler Imaging Assessment of Changes of Blood Flow in Adenomyosis After Higher-Dose Oxytocin: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Ultrasound Med. 2022, 41, 2413–2421.

- Lu, A.-P.; Jia, H.-W.; Xiao, C.; Lu, Q.-P. Theory of traditional Chinese medicine and therapeutic method of diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 1854.

- Mahar, K.M.; Enslin, M.B.; Gress, A.; Amrine-Madsen, H.; Cooper, M. Single- and Multiple-Day Dosing Studies to Investigate High-Dose Pharmacokinetics of Epelsiban and Its Metabolite, GSK2395448, in Healthy Female Volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2017, 7, 33–43.

- Mansouri, R.; Santos, X.M.; Bercaw-Pratt, J.L.; Dietrich, J.E. Regression of Adenomyosis on Magnetic Resonance Imaging after a Course of Hormonal Suppression in Adolescents: A Case Series. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015, 28, 437–440.

- Mao, X.; Wang, Y.; Carter, A.V.; Zhen, X.; Guo, S.-W. The Retardation of Myometrial Infiltration, Reduction of Uterine Contractility, and Alleviation of Generalized Hyperalgesia in Mice with Induced Adenomyosis by Levo-Tetrahydropalmatine (l-THP) and Andrographolide. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 18, 1025–1037.

- Marjoribanks, J.; Ayeleke, R.O.; Farquhar, C.; Proctor, M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD001751.

- Nie, J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.-W. Immunoreactivity of progesterone receptor isoform B, nuclear factor κB, and IκBα in adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 886–889.

- Jichan, N.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.-W. Immunoreactivity of oxytocin receptor and transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 and its correlation with dysmenorrhea in adenomyosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 346.e1–346.e8.

- Asher, O.; Weber-Schöndorfer, C. 2.15—Hormones. In Drugs during Pregnancy and Lactation, 3rd ed.; Schaefer, C., Peters, P., Miller, R.K., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 413–450.

- Osuga, Y.; Fujimoto-Okabe, H.; Hagino, A. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of dienogest in the treatment of painful symptoms in patients with adenomyosis: A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 673–678.

- Osuga, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Kanda, S. Long-term use of dienogest for the treatment of primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 606–617.

- Osuga, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Hagino, A. Long-term use of dienogest in the treatment of painful symptoms in adenomyosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2017, 43, 1441–1448.

- Ozdegirmenci, O.; Kayikcioglu, F.; Akgul, M.A.; Kaplan, M.; Karcaaltincaba, M.; Haberal, A.; Akyol, M. Comparison of levonorgestrel intrauterine system versus hysterectomy on efficacy and quality of life in patients with adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 497–502.

- Park, C.W.; Choi, M.H.; Yang, K.M.; Song, I.O. Pregnancy rate in women with adenomyosis undergoing fresh or frozen embryo transfer cycles following gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2016, 43, 169.

- Phiel, C.J.; Zhang, F.; Huang, E.Y.; Guenther, M.G.; Lazar, M.A.; Klein, P.S. Histone deacetylase is a direct target of valproic acid, a potent anticonvulsant, mood stabilizer, and teratogen. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 36734–36741.

- Reinhold, C.; Atri, M.; Mehio, A.; Zakarian, R.; Aldis, A.E.; Bret, P.M. Diffuse uterine adenomyosis: Morphologic criteria and diagnostic accuracy of endovaginal sonography. Radiology 1995, 197, 609–614.

- Reinhold, C.; McCarthy, S.; Bret, P.M.; Mehio, A.; Atri, M.; Zakarian, R.; Glaude, Y.; Liang, L.; Seymour, R.J. Diffuse adenomyosis: Comparison of endovaginal US and MR imaging with histopathologic correlation. Radiology 1996, 199, 151–158.

- Sharara, F.I.; Kheil, M.H.; Feki, A.; Rahman, S.; Klebanoff, J.S.; Ayoubi, J.M.; Moawad, G.N. Current and Prospective Treatment of Adenomyosis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3410.

- Shawki, O.; Igarashi, M. Danazol loaded intrauterine device (IUD) for management of uterine adenomyosis: A novel approach. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 77, S24.

- Shen, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.-W. Transforming growth factor β1 signaling coincides with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in the development of adenomyosis in mice. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 355–369.

- Spitz, I.M.; Grunberg, S.M.; Chabbert-Buffet, N.; Lindenberg, T.; Gelber, H.; Sitruk-Ware, R. Management of patients receiving long-term treatment with mifepristone. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 84, 1719–1726.

- Stratopoulou, C.A.; Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.-M. Origin and Pathogenic Mechanisms of Uterine Adenomyosis: What Is Known So Far. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 2087–2097.

- Struthers, R.S.; Nicholls, A.J.; Grundy, J.; Chen, T.; Jimenez, R.; Yen, S.S.C.; Bozigian, H.P. Suppression of gonadotropins and estradiol in premenopausal women by oral administration of the nonpeptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist elagolix. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 545–551.

- Sun, X.; Bartos, A.; Whitsett, J.A.; Dey, S.K. Uterine deletion of Gp130 or Stat3 shows implantation failure with increased estrogenic responses. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 1492–1501.

- Szyf, M. Therapeutic implications of DNA methylation. Future Med. 2005, 1, 125–135.

- Calderon, L.; Netter, A.; Grob-Vaillant, A.; Mancini, J.; Siles, P.; Vidal, V.; Agostini, A. Progression of adenomyosis magnetic resonance imaging features under ulipristal acetate for symptomatic fibroids. Reprod. BioMed. Online 2021, 42, 661–668.

- Tsui, K.-H.; Lee, W.-L.; Chen, C.-Y.; Sheu, B.-C.; Yen, M.-S.; Chang, T.-C.; Wang, P.-H. Medical treatment for adenomyosis and/or adenomyoma. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 53, 459–465.

- Tunnicliff, G. Actions of sodium valproate on the central nervous system. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1999, 50, 347–365.

- Vannuccini, S.; Luisi, S.; Tosti, C.; Sorbi, F.; Petraglia, F. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 398–405.

- Vannuccini, S.; Petraglia, F. Recent advances in understanding and managing adenomyosis. F1000Research 2019, 8, 283.

- Vannuccini, S.; Tosti, C.; Carmona, F.; Huang, S.J.; Chapron, C.; Guo, S.-W.; Petraglia, F. Pathogenesis of adenomyosis: An update on molecular mechanisms. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2017, 35, 592–601.

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, S. The influence of mifepristone to caspase 3 expression in adenomyosis. Clin. Exp. Obs. Gynecol. 2014, 41, 154–157.

- Wong, C.L.; Farquhar, C.; Roberts, H.; Proctor, M. Oral contraceptive pill for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, Cd002120.

- Wu, Y.; Halverson, G.; Basir, Z.; Strawn, E.; Yan, P.; Guo, S.-W. Aberrant methylation at HOXA10 may be responsible for its aberrant expression in the endometrium of patients with endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 371–380.

- Wu, Y.; Strawn, E.; Basir, Z.; Halverson, G.; Guo, S.-W. Promoter hypermethylation of progesterone receptor isoform B (PR-B) in endometriosis. Epigenetics 2006, 1, 106–111.

- Wu, Y.; Strawn, E.; Basir, Z.; Halverson, G.; Guo, S.W. Aberrant expression of deoxyribonucleic acid methyltransferases DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B in women with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 87, 24–32.

- Liu, X.; Yuan, L.; Guo, S.-W. Valproic Acid as a Therapy for Adenomyosis: A Comparative Case Series. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 17, 904–912.

- Ying, P.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Lu, S.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Y. Qiu’s Neiyi Recipe Regulates the Inflammatory Action of Adenomyosis in Mice via the MAPK Signaling Pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. Ecam 2021, 2021, 9791498.

- Younes, G.; Tulandi, T. Effects of adenomyosis on in vitro fertilization treatment outcomes: A meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 483–490.e3.

- Zhu, B.; Chen, Y.; Shen, X.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.-W. Anti-platelet therapy holds promises in treating adenomyosis: Experimental evidence. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. RBE 2016, 14, 66.

- Zhu, Y.P.; Wu, Y.P. Effect of Neiyi prescription of QIU on expressions of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 in rats with endometriosis. Chin. Arch. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2013, 31, 644–646.

- Łupicka, M.; Socha, B.; Szczepańska, A.; Korzekwa, A. Prolactin role in the bovine uterus during adenomyosis. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2017, 58, 1–13.

- Zani, A.C.T.; Valerio, F.P.; Meola, J.; da Silva, A.R.; Nogueira, A.A.; Candido-dos-Reis, F.J.; Poli-Neto, O.B.; Poli-Neto, J.C. Impact of Bevacizumab on Experimentally Induced Endometriotic Lesions: Angiogenesis, Invasion, Apoptosis, and Cell Proliferation. Reprod Sci. 2020, 27, 1943–1950.

More