Design Thinking (DT) is a design process originally used in the conception and validation of innovative and technologically efficient human-centered solutions for ill-formed problems. Being an iterative and collaborative process with a human point of view, DT allows adopters to improve several intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, like collaboration, creative thinking, leadership, presentation, project management, ethics, storytelling, negotiation, empathy, willingness to learn, etc. As such, DT has been adopted in several other areas and has also become highly relevant in educational contexts to develop the aforementioned skills in students. It has also been shown to contribute to minimizing the school dropout problem by keeping students motivated and integrated in the school context.

- Design Thinking

- active learning

- secondary education

- School Dropout

1. Introduction

2. Design Thinking

-

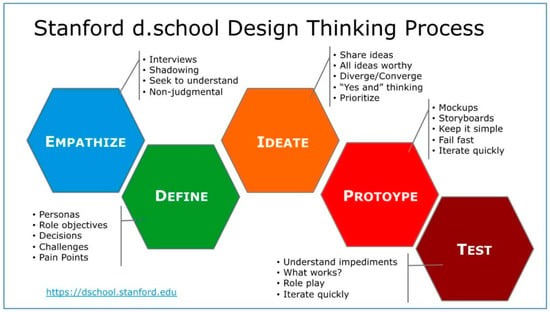

Stage 1: Empathize—the first step is related to understanding the real needs of a specific group. This helps to gain an empathetic understanding of the problem through research, observations, interviews, or any other process that allows understanding the problem from the users’ point of view.

-

Stage 2: Define—the second step is related to defining the problems based on the research performed in the first step. This includes introducing a problem statement based on the perspective gained previously.

-

Stage 3: Ideate—the third step is related to introducing solutions to problems. This includes “thinking out of the box” and searching for alternatives and identifying innovative solutions to problems. In the end, a decision is made to implement in the next step.

-

Stage 4: Prototype—the fourth step is related to building a representation of the idea conceived in the previous step in the form of a product, service, project, framework or other.

-

Stage 5: Test—the last step is related to implementing the solution and testing it through the involvement of the users. If the solution proves to be not adequate for the problem, it implies returning to a previous DT step.

3. Design Thinking and Early School Dropout

Early school dropout (ESD) is defined as a situation in which a student stops attending school without having completed the minimal required qualification. ESD is a very complex and multifaceted phenomenon that results from a combination of social, economic, educational, and even personal (family) factors. In fact, although it is often associated with socioeconomic disadvantages, the decision is rarely sudden or the result of an isolated episode and normally originates from a long (and quite visible) process of disinterest and failure. The six main causes that have been proposed for ESD are (1) a mismatch between school and student reality; (2) poor family cooperation with the school; (3) an inadequate response of the school to the expectations of teachers and students, families, or society; (4) poor pedagogical preparation of teachers; (5) a lack of reading habits; and (6) a lack of study methods [28][26]. Other frequent causes are related to special needs not being catered to; personal or family-related problems; bad relations with professors; poor relationships with peers or a negative school climate (including the existence of bullying); health problems and dissatisfaction with the results obtained; socioeconomic status, such as a lack of money to continue school or having to start to work at an earlier age to help in the household; the cultural identity of the family, which can enter into conflict with the school system; and family members’ dedication to, and expectations of, the student [29][27]. In 2010, the goal of the European Union was to lower the early school dropout rate below 10% by 2020. The “European Toolkit for Schools” was created with an aim to promote inclusive education and combat ESD. This guide provides useful information, examples of measures, reference materials, and a set of tools with concrete ideas aimed at improving the actions of schools to enable all students to be successful. The support students receive from teachers is the most important enhancer of school engagement. This strong relationship is linked to social, emotional, and behavioral well-being and attitudes. Increasingly, teachers are expected to become facilitators of learning [30][28]. By continually motivating, guiding, and supporting students, teachers can help students to control their own learning. This approach requires teachers to develop a strong, trust-based relationship with students and their parents, thereby developing positive environments in classrooms and schools. Students’ needs are presented as the central focus of education. All students are entitled to high-quality teaching, a relevant curriculum, appropriate assessment, and valuable learning opportunities. Schools must provide an environment that accommodates the diversity of students, including their various learning needs, to maximize the potential of each young person. Quality education must be designed and tailored to students, rather than forcing them to adjust to an existing system. This approach should guarantee their participation in the learning process, as well as the perception of a clear purpose for their studies. These are important incentives for their permanence in the school system, and a support framework should be in place that consists of a wide range of different measures for different groups of students. By adopting DT in the classroom, the educational model is enriched by making the object of discovery fascinating and involving, motivating, and guiding the students as “design thinkers” towards personal and educational success. Thus, DT becomes a glue that keeps teams together, allowing students to take intuitive leaps, think differently, and see old problems in new ways. This promotes students’ creative confidence, achieved through active problem solution promotion, while combating early-school leaving, as teachers can create a more immersive curriculum focused on real-world problem-solving, where students can solve creatively and infuse meaning into what students learn, regardless of the subject or grade. One of the justifications for dropping out of school is the inadequacy of the teaching method for some students [28][26]. Therefore, the whole learning process should be adapted to the reality of teachers and students. The DT methodology can be of acute importance to changing the early school dropout scenario, as it stimulates innovation and the search for the most suitable solutions for the most varied types of problems. The Design Thinking methodology is by nature multidisciplinary; hence, it can be implemented in a vast series of contexts and supportive of people from different backgrounds and with different goals. Since a main educational problem is to have adequate learning techniques that boost and support students’ learning, the application of the DT methodology, as it promotes greater engagement and more active participation of students in the learning process, will, by deduction, avoid the early school dropout of students. By using the Design Thinking methodology, students are more integrated in the learning process because they develop their skills through a problem-solving approach based on real-life situations while immersed in a collaborative environment. To sum up, changing the curriculum to integrate DT within the traditional school system can lower school dropout rates as DT is an innovative learning process that is adapted not only to the students’ reality, but also to the teachers’. In fact, when educators are exposed to DT methodology, they are better able to conceptualize individual ideas and perspectives on various topics. They acquire the ability to plan more dynamic classes that are in accordance with the level of knowledge of all those involved. As such, DT is one of the most efficient ways to transform teaching and empower teachers.References

- Vaz de Carvalho, C.; Bauters, M. Technology to Support Active Learning in Higher Education. In Technology Supported Active Learning; Lecture Notes in Educational, Technology; Vaz de Carvalho, C., Bauters, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021.

- Piaget, J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children; International Universities Press: Madison, CT, USA, 1952.

- Brame, C. Active learning. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. 2016. Available online: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/active-learning/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978.

- Blikstein, P. Digital fabrication and “making” in education: The democratization of invention. FabLabs Mach. Mak. Invent. 2013, 4, 245–263.

- Meinel, C.; Leifer, L.; Plattner, H.; Meinel, D. Design Thinking for Innovation: Research and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017.

- Faria, M.; Novo, C.; Lopes, A.; Moura, A.; Tsalapatas, H.; Heidmann, O.; Vaz de Carvalho, C. A utilização de Design Thinking para promover a adoção de práticas sustentáveis no Ensino Básico e Secundário. Rev. Ibér. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2023, E57, 217–230.

- Li, T.; Zhan, Z. A systematic review on design thinking Integrated Learning in K-12 education. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8077.

- Baričević, M.; Luić, L. From Active Learning to Innovative Thinking: The Influence of Learning the Design Thinking Process among Students. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 455.

- Androutsos, A.; Brinia, V. Developing and Piloting a Pedagogy for Teaching Innovation, Collaboration, and Co-Creation in Secondary Education Based on Design Thinking, Digital Transformation, and Entrepreneurship. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 113.

- Brown, T. Design thinking. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 84–92.

- Guaman-Quintanilla, S.; Everaert, P.; Chiluiza, K.; Valcke, M. Fostering Teamwork through Design Thinking: Evidence from a Multi-Actor Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 279.

- Dorst, K. The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Des. Stud. 2011, 32, 521–532.

- Liedtka, J. Perspective: Linking design thinking with innovation outcomes through cognitive bias reduction. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 1068–1083.

- Kelley, D.; Kelley, T. Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Schütte, S.; Fraefel, N.; Meinel, C. Design thinking in the classroom: An analysis of students’ long-term retention and application of design thinking concepts. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2596.

- Tsalapatas, H.; Heidmann, O.; Pata, K.; Vaz de Carvalho, C.; Bauters, M.; Papadopoulos, S.; Katsimendes, C.; Taka, C.; Houstis, E. Teaching Design Thinking through Gamified Learning. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019); SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications, Lda.: Heraklion, Greece, 2019; pp. 278–283, ISBN 978-989-758-367-4.

- d.school. An Introduction to Design Thinking Process Guide. 2023. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/files/509554.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Plattner, H.; Meinel, C.; Leifer, L. (Eds.) Design Thinking: Understand—Improve—Apply; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011.

- Tramonti, M.; Dochshanov, A.M.; Zhumabayeva, A.S. Design Thinking as an Auxiliary Tool for Educational Robotics Classes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 858.

- Bonwell, C.C.; Eison, J.A. Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom; ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1; George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 1991.

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.L.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M.K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M.P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8410–8415.

- Vallecillo, N.R. Aplicación de Design Thinking Para la Sistematización de Procesos Artísticos en el Alumnado de Secundaria. Revista de Investigación en Educación. 2020, pp. 24–39. Available online: http://revistas.webs.uvigo.es/index.php/reined/article/view/2628 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Mena, O.M. Design thinking: Un enfoque educativo en el aula de segundas lenguas en la era pos-COVID. Tecnol. Cienc. Educ. 2021, 18, 45–75.

- Moreira, A.R.A. O Papel da Criatividade e do Design Thinking na Inovação; FEUP: Porto, Portugal, 2015.

- Rocha, M.; Ferreira, A.; Moreira, A.; Gomes, T. Redução do Abandono Escolar Precoce-Uma Meta a Prosseguir, Estudos e Intervenções. RH+50. 2014. Available online: https://iefp.eapn.pt/docs/Combate_ao_abandono_escolar_precoce.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Pereira, M.; Cezareti. Evasão Escolar: Causas e Desafios. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. 1, 36–51. Available online: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/wp-content/uploads/kalinspdf/singles/evasao-escolar.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- School Education Gateway, Practical Approaches to Early School Dropout Prevention. Available online: https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/pt/pub/teacher_academy/catalogue/detail.cfm?id=227520 (accessed on 30 January 2022).